Spycops: Your Name’s Down but You’re Not on the List

The public inquiry into Britain’s political secret police is publishing more names of undercover officers. Despite this, their list of known

Is this is a catalogue of innocent incompetence despite spending £17m? Or deliberate obfuscation to protect the wrongdoers whose deeds the Inquiry exists to expose?

Whichever, it adds to the list of obstructions that have been the hallmark of this Inquiry.

TOO LITTLE TOO LATE

Last week the Undercover Policing Inquiry (UCPI) named the officer previously known as HN78. ‘Anthony “Bobby” Lewis’ is the only known black officer in the history of Britain’s political secret police. He spied on Stephen Lawrence’s family campaign as part of his infiltration of the Socialist Workers Party and Anti-Nazi League between 1991 and 1995.

There are known to have been at least 139 undercover officers in the 50 year history of the spycops units the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) & National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU). Lewis is the 26th to have infiltrated the Socialist Workers Party, which means – even ignoring all as-yet unnamed officers – nearly 20% of all spycops targeted that one organisation. It is, by far, the most targeted group, attracting far more attention than the entirety of the far right.

The Inquiry was announced by the Home Secretary more than five years ago and was originally expected to have finished in summer 2018. Last week the Inquiry said it is hoping to start properly in summer 2020. We expect the final report to be published around 2025.

The release of Lewis’ fake name comes more than a year after the Inquiry decided to do it. With their new natty graphics on Twitter, the casual observer might think the Inquiry was starting to become more communicative with the public whose funds it so ravenously consumes.

However, they still haven’t even published a complete list of the officer names that they’ve agreed to publish. Their incomplete list that does exist doesn’t link to any further information on the officers (not even the stuff the Inquiry has published elsewhere on the same site). It is given in order of the officers’ fake surnames, and is not interactive, so you can’t order it by year of deployment, group infiltrated, or even just first name.

THE TRUTH, NOT THE WHOLE TRUTH

Additionally, the list of groups for each officer is incomplete. For example, for ‘Andy Davey’ – the undercover identity of officer Andy Coles – it only lists animal rights groups, but his brief as given in an internal SDS document was ‘Anarcho/ Animal rights/ Environmentalist & Pacifist’.

Coles spent a lot of time infiltrating various environmental and peace groups and going on their demos. However, if people from those

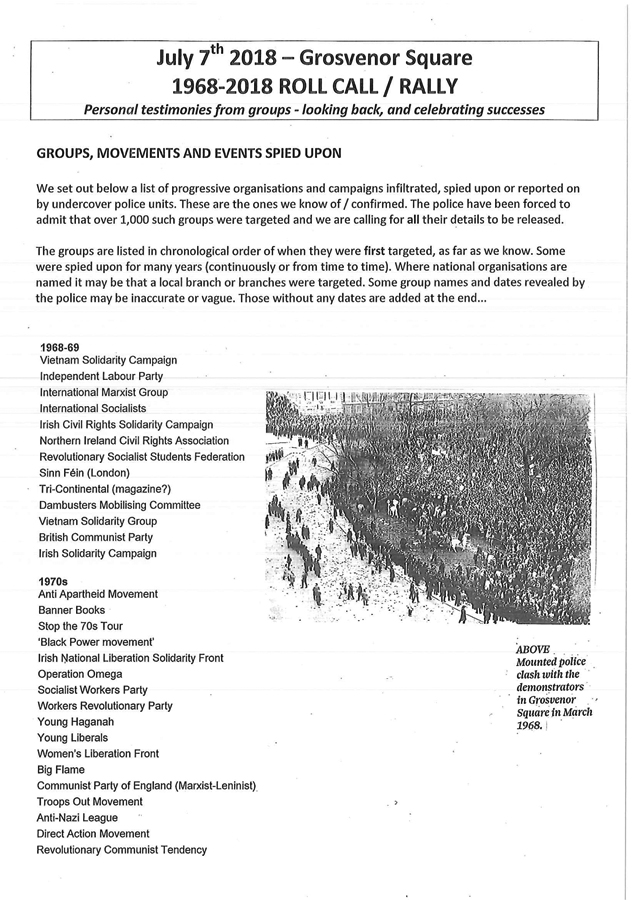

Photo: Noor Admani. Copyright: Peace News

Most of the

Also, because of the organic and intertwined way many of the groups were/are

Organisations like the Socialist Workers Party (and their forerunner International Socialists) were specifically targeted over the years because of their involvement in a wide variety of then-current campaigns.

For a spycop, a position next to a key organiser who knew a lot of people was a goldmine, they would get insights into how things were set up and who were the key players. Chumming up with such organisers also meant that the undercover officer could ask their buddy about people of interest, instead of having to approach that person directly with questions that could raise suspicion.

FILLING THE GAPS

The Undercover Research Group and the Guardian made a list of the groups targeted by

We keep our post How Many Spycops Have There Been? updated as new names are revealed. It currently stands at 75 named officers out of the total of 139.

Beyond our simple list, the Undercover Research Group have collated the Inquiry’s documents that use code numbers with ‘N’ prefixes for officers. They’ve collated the information along with that of independent researchers produced a more complete rundown of the N-numbered officers.

They have also made an interactive spycops timeline that shows which officers were deployed when and into what political movements. Just imagine what a thorough job the URG could do with a decent fraction of the millions that the Inquiry has wasted. If you’d like to help them, you can donate.

The Inquiry list contains the names used by 68 officers. Fifty of the others have already been granted total anonymity, so the Inquiry will not even publish their fake name. The Inquiry is going to withhold almost all officers’ real names. This means that, even if their deeds become known, they will not be held to account.

Victims of spycops, and the wider public, deserve the truth about what was done to them. The Inquiry is more concerned with protecting abusive officers from suffering any consequences of their abuses. We should all be given the fullest information.

Here’s what we know is missing from the Inquiry’s list of Special Demonstration Squad spycops.

SPYCOPS NOT MENTIONED AT ALL BY THE INQUIRY

These four officers may be among those identified by the Inquiry’s anonymising N-numbers, but there aren’t enough details given for researchers to be able to identify them. If this is deliberate then, given that their names have long been in the public domain, it is ludicrous.

“RC”

‘RC’ was involved in animal rights campaigns around Oxford 2002-06. Like so many

“Gary R” & “Abigail L”

‘Gary R’ appears to have been the successor to ‘RC’ in Oxford. He was joined for some of the time by a partner, ‘Abigail L’. They were exposed in July 2016. As with ‘RC’, researchers are withholding full names in case of the unlikely event that they’ve misidentified them.

Full profile of ‘Gary R’ & ‘Abigail L’.

These three officers are likely to have been from the National Public Order Intelligence Unit. Though they worked in parallel with the SDS performing the same function, and indeed some personnel moved between the two, the Inquiry has been much more secretive about this unit. There is no significant information on the NPOIU from the Inquiry that wasn’t already uncovered by activists and researchers.

“Mike Ferguson”

This SDS officer infiltrated the

The campaign was chaired by Peter Hain, later to become a Labour MP and

After a plan to throw smoke bombs and metal tacks onto a pitch got rumbled by police, Hain

‘Ferguson’ was exposed in True Spies, a 2002 BBC documentary series on the SDS [transcript, video]. Hain is one of 200 significantly affected people who have been made core participants at the Inquiry. They acknowledged ‘Ferguson’ when granting Hain this status, yet have not mentioned him anywhere else before or since.

In 2015, ‘Ferguson’s daughter wrote an article for the Guardian about growing up with a

CONFIRMED BY INQUIRY BUT MISSING FROM THEIR LIST

The Inquiry’s list only covers undercover officers of the SDS. In their most recent Update Note, the Inquiry said it will publish a table of NPOIU officers ‘in due course’. The following four officers from the NPOIU have already been officially confirmed by the Inquiry, but they are not included in the cover names list.

Mark Kennedy aka “Mark Stone”

The NPOIU officer whose unmasking in 2010 caused the whole

Kennedy worked in at least 11 countries beyond the Inquiry’s remit of England and Wales. He was arrested several times during his time

After he left the police, he continued spying on the same activist community for corporate paymasters until he was caught by suspicious comrades.

“Rod Richardson” HN 596

(Inquiry also refer to him as EN 36)

‘Rod Richardson’ infiltrated environmental, anarchist and animal rights groups from 2000-2003, as Mark Kennedy’s predecessor. He is one of – if not the very – first officers in the NPOIU. He was trained by Andy Coles, the SDS officer who’d updated that unit’s Tradecraft Manual after his own deployment ended in 1995.

Coles instructed him to use a technique that was, by then, anachronistic; stealing the identity of a dead child as the basis of a fake persona. In the online age, this became hugely risky, and it was a

The Met refused to confirm or deny it, much to the distress of the mother of the real Rod Richardson who had died as a baby.

In December 2016, the Inquiry confirmed that ‘Rod Richardson’ was an undercover officer of the NPOIU. His name, photo

“Lynn Watson” EN34

Based in Leeds from 2002-06, ‘Lynn Watson’ infiltrated environmental, anti-capitalist and peace groups, and was treasurer of The Common Place, a political social

She was especially active in the Clandestine Insurgent Rebel Clown Army, and there is

As well as being arrested on a couple of climate change protests, she also committed an offence under the Companies Act 2006 by filing the Common Place’s accounts under a false identity.

Her name and picture were published in the mainstream media in 2011. There was a ten-page section devoted to her deployment in the 2013 book Undercover: The True Story of Britain’s Secret Police by Guardian journalists Rob Evans & Paul Lewis.

Despite all this public knowledge, it wasn’t until 30 October 2018 the Inquiry confirmed her identity by name as it granted her core participant status. The Inquiry will not be publishing her real name.

“Marco Jacobs” HN 519

‘Marco’ began his deployment in Brighton in 2004, but after failing to fit in he was redeployed to Cardiff. There, he involved himself in a range of anti-war, anarchist and other causes.

In a dramatic court hearing in 2015 – presided over by Sir John Mitting who would later become Chair of the public inquiry – police conceded they wouldn’t contest the assertion that ‘Jacobs’ was a

As with ‘Lynn Watson’, ‘Jacobs’ had his cover name, photo

COVER NAME LISTED BUT REAL NAME IS ALSO KNOWN

“Peter Johnson”, “Peter Daley”, “Peter Black” HN 43

Real name: Peter Francis. On Twitter @realspycop

“Jim Sutton” HN 14

Real name: Jim Boyling

“Mark Cassidy” HN 15

Real name: Mark Jenner

“Bob Robinson” HN 10

Real name: Bob Lambert

“John Barker” HN 5

Real name: John Dines

“Mike Blake” HN 11

Real name: Mike Chitty

“Roger Thorley” HN 85

Real name: Roger Pearce

“Andy Davey” HN 2

Real name: Andy Coles

ON THE INQUIRY LIST BUT WITHOUT A NAME

HN 89

This SDS officer infiltrated the far-right in the 1990s. He is now dead. No application has been made by the family to withhold the real name or the cover name. The Inquiry said in November 2017 that it was intending to publish both.

The last two officers to be named by the Inquiry were Paul Gray and Bobby Lewis – both over a year after the Inquiry had announced its decision to do so. How much longer we’ll have to wait for HN 89 is anyone’s guess. We know that waiting for the full truth will take a lot longer, and it will not be something delivered by the Inquiry.

Kate’s human rights claim is being heard by the

Kate’s human rights claim is being heard by the