UCPI Daily Report, 5-10 Nov 2025: James Thomson evidence

James Thomson (centre, Barbour jacket, looking at camera) after his spycop career, working as a protection officer for Tony Blair, Dublin, September 2010

INTRODUCTION

Special Demonstration Squad officer HN16 James Thomson ‘James Straven’ was deployed 1997-2002, infiltrating London-based animal rights groups. He deceived several women into long-term intimate relationships.

He gave evidence to the Undercover Policing Inquiry over three days: 5, 6 and 10 November 2025. His evidence was broadcast audio-only in order to protect his privacy.

It is not clear why the Inquiry chose to pander to the desires of this abusive perpetrator and deny the public video access to important evidence, despite Thomson’s relatively recent photo and real name being in the public domain.

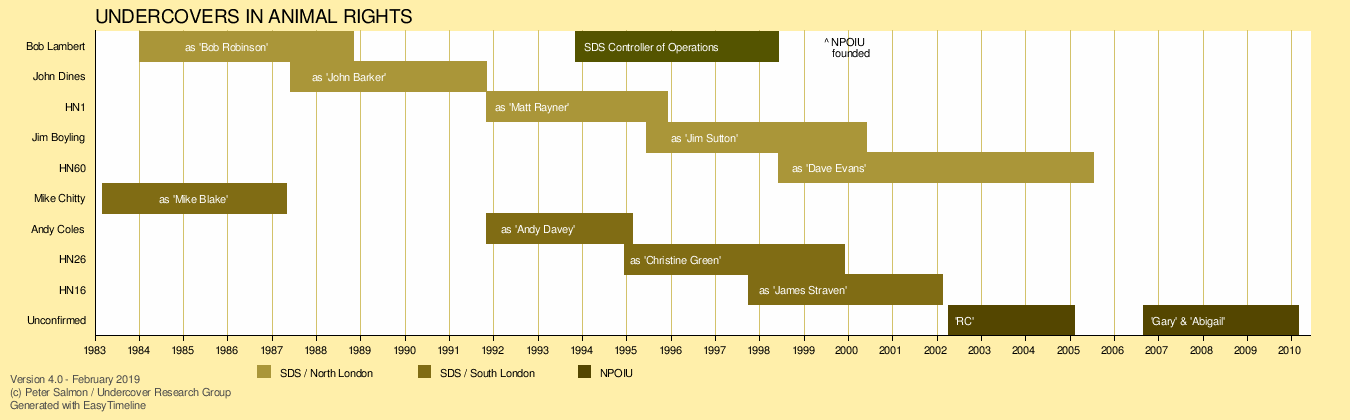

The Undercover Policing Inquiry (UCPI) is an independent, judge-led inquiry into undercover policing in England and Wales. Its main focus is the activity of two units who deployed long-term undercover officers into a variety of political groups: the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS, 1968-2008) and the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU, 1999-2011). Spycops from these units lived as activists for years at a time, spying on more than 1,000 groups.

This hearing was part of the Inquiry’s ‘Tranche 3 Phase 1’, which is examining the final 15 years of the Special Demonstration Squad, 1993-2008.

Thomson was questioned by Counsel to the Inquiry, David Barr KC. The full transcripts and audio for each day can be found on the Inquiry’s hearing pages for 5 November, 6 November, 10 November.

David Barr KC, Counsel to the Inquiry

As there is no video from the hearings, it is important to report that spectators in the public gallery described Thomson answering many of the initial questions with a smirk or a wry smile. From his body language, he appeared to be enjoying himself, being asked about his time as an undercover officer.

But later on, as the questioning moved on to the many serious matters of his multiple wrongdoings, his demeanour changed, and he became visibly less comfortable. This is the kind of important detail the public misses when the Inquiry refuses to broadcast video of the spycops giving their evidence.

When specific documents are mentioned in this report, we give their Inquiry reference numbers. If the Inquiry has published them, the numbers are hyperlinked.

However, at the time of publication, three months after the hearings, the majority of the 67 documents we cite in this report are still unpublished. It is absurd that the Inquiry thinks it is fulfilling its purpose when it hasn’t got round to publishing the evidence it is citing.

Questioning went back and forth on topics a lot over the three days, so this report has been organised according to themes in the evidence rather than going through it day by day.

This is a long report. Use the links below to jump to a particular topic.

A Known Liar

The major lies told before the hearing began

Misuse of Fake Identities

Stealing Kevin Crossland’s identity long before Thomson was undercover, fraudulent use of documents

Abusive Relationships

Sara, Wendy and Ellie; harassment and manipulation after his deployment ended

Targeting and Deployment

Hunt saboteurs, Shamrock Farm, the growing remit of the NPOIU

Participation in Crime

Public disorder and ‘Operation Lime’ – the gunpowder plot

Foreign Travel

Going abroad with and without authorisation

Intelligence and Tradecraft

Low value reports, racism, sexism, and violation of legal privilege

HN26 ‘Christine Green’

Thomson’s contemporary who left the police to marry a hunt sab

Management Accountability & Post-Deployment Dishonesty

Introduction of RIPA regulations, withdrawal and disciplinary action, claims about mental health

Conclusions

The absence of conscience, remorse and credibility

A Known Liar

At the start of this set of hearings in October 2025, David Barr KC’s opening statement to Tranche 3 gave a summary of what would be heard in the following weeks. He singled out Thomson’s dishonesty:

‘One thing is certain: Mr Thomson has, on his own admission, told many lies to date. He has lied not only to those he mixed with whilst deployed but also to his managers and to the Inquiry. His credibility is very much an issue.’

Now that Thomson was at the Inquiry in person, Barr began by reading Thomson’s witness statement into the evidence. He specified:

‘You have provided a witness statement to the Inquiry, in fact a series of witness statements. I am referring to the last and the longest of those witness statements.’ [UCPI0000035553].

Barr later noted that several of Thomson’s written statements were retractions of lies he had told in previous statements, offering excuses for his mendacious behaviour.

Thomson was questioned about many issues that arose from the evidence of ‘Sara’, ‘Ellie’, ‘Wendy’, ‘L3’, and Liisa Crossland who we heard from in previous hearings.

Barr went on to explore those lies with him in more detail on the last day of questioning. We were shown Thomson’s October 2017 witness statement to the Inquiry [UCPI0000035199]. In it, he asserted that he never had inappropriate relationships with Sara, Ellie or Wendy, and even claimed to have never heard Ellie’s name.

Thomson admitted these were bare-faced lies, and that he deliberately and dishonestly sought to mislead the Inquiry. He claims this was to avoid being exposed as having conducted deceitful sexual relationships and losing his anonymity, and tries to suggest it was only ever intended to be a temporary lie.

We were then shown a statement he made in April 2018 [UCPI0000035223]. In it, Thomson states:

‘This statement is intended to correct parts of the account I submitted to the Inquiry immediately before the closed hearing on 17th October 2017, held to consider my application for anonymity, and as importantly to allow me to apologise to the Inquiry for my comments in particular, and my approach in general.’

Barr asked Thomson why he made that apology:

‘Q. Was it also to try to give the impression to the Inquiry that you were contrite and now coming clean?

A. I was contrite.

Q. And coming clean?

A. I hope so.

Q. Let’s have a look at that.’

In the second statement Thomson admitted he did have relationships with Sara and Ellie, but described the former as ‘a brief sexual relationship over a few weeks’ and the latter as ‘lasting a number of months’. There is no mention that he had sex with Ellie as late as 2015, fifteen years after the relationship began.

Barr pointed out that the apology came after the Inquiry had written to Thomson to inform him that his cover name would be made public. It was only a matter of time before Ellie and Sara would be able to tell the Inquiry about the relationships themselves.

The fact that Thomson has repeatedly told proven lies to the Inquiry in the past clearly framed Barr’s approach to his answers during the hearings, and set the tone for all of the evidence we heard over the three days.

Misuse of Fake Identities

Thomson committed a dizzying list of deceitful, fraudulent and illegal acts while undercover, involving the creation of false identities and the manipulation of ID documents.

Thomson used the official cover name ‘James Straven’. He says that creating an undercover persona by stealing a dead child’s identity was briefly mentioned to him when he was first sounded out for joining the SDS, but he never spoke again to any other SDS officers about how to do it.

The practice was no longer in use when he joined. When he was creating his ‘legend’ he was directly told by his managers HN216 Keith Edmondson and HN10 Bob Lambert not to steal a dead child’s identity.

‘James Straven’ was a fictitious identity, not based on any real individual, and he is not aware of anyone ever researching or testing the ‘James Straven’ legend.

KEVIN CROSSLAND

Kevin Crossland, shortly before he was killed in 1966

Despite this, Thomson did use an alternative (and seemingly unauthorised) identity, ‘Kevin Crossland’, which he stole from a dead child.

The real Kevin Crossland died in a plane crash in Ljubljana, Yugoslavia in 1966, when he was 5 years old. We heard evidence from Liisa Crossland on 4 November about Kevin’s life and the damage Thomson has caused her family.

One extremely striking feature of Thomson’s theft of Kevin Crossland’s identity is that he seemingly obtained the birth certificate in 1991, five years before he joined the SDS. This strongly suggests that he was already corrupt and criminally minded, even before he became an undercover officer.

A copy of Kevin’s birth certificate [MPS-0526867] was made on 9 July 1991. Barr pointed out that it bears a Special Branch reference number, SB/309/476.

Thomson claims he does not know what that number is, but states that he would have made the copy as a fairly junior operative in Special Branch, insisting he doesn’t remember how he came across it, nor how he still had it in his possession when he joined the SDS five years later.

We were then shown Kevin’s death certificate [UCPI0000038350] which records the death occurring in a plane crash in Ljubljana. In his witness statement, Thomson says he knew Kevin had died abroad, but in his oral evidence he claimed this may be the first time he had seen the death certificate and that he couldn’t remember whether he knew that Kevin died in a plane crash.

Thomson says he wants to apologise again to Liisa Crossland and knows how hard it must have been for her to give evidence. However, his apology was significantly undermined by the evidence we then heard about his extensive and apparently criminal misuse of Kevin’s identity.

We were shown an Experian search for electoral roll information [MPS-0722300]. It shows two names registered at James Thomson’s cover address: James Straven and Kevin Crossland. Neither man existed, both were fake identities being used by Thomson.

From 2000-2003, James Straven and Kevin Crossland were on the electoral roll together at Flat 2, 25 Southey Road, London SW9 0PD. Neither of them existed; they were two identities used by spycop James Thomson.

Thomson says he knew it was wrong and illegal to register Crossland’s name on the electoral roll, and that he did this so he could use the Crossland identity if he was ever arrested, to do bail checks.

However, the one time we know he was arrested, he gave the name ‘James Straven’.

We were shown records of both ‘James Straven’ and James Thomson making payments to what appear to be private detective agencies [MPS-0719722] (Thomson claims this is a mistake and he was in fact buying flagstones for his garden).

However, he does not deny that, by the time of his SDS deployment ending in early 2002, he had applied for a driving licence and attempted to open a bank account in the name of Kevin Crossland.

Letter from London Electricity confirming supply in the name of Kevin Crossland, 23 January 2002

We were shown a letter from London Electricity saying Kevin Crossland had been the registered customer at James Thomson’s cover address since 28 January 2001, and a letter from British Telecom about registering a phone line in the name of Kevin Crossland.

Crossland was also the name on council tax bills and water bills for Thomson’s cover address (all these utility documents are in MPS-0526867).

Thomson agrees that he knew at the time that all of this was illegal. It never occurred to him that it was immoral, but he says he realises that now.

Thomson’s theft of the Crossland identity was uncovered by his managers and he was challenged on it in early 2002. A meeting note from 19 March 2002 [MPS-0745388] records Thomson claiming he had stolen Kevin Crossland’s identity for ‘operational safety’. Thomson now says this claim was a lie.

He says he struggled with management generally, and that he cannot rationalise now what his plans were for the Crossland identity.

He admits that he wanted to retain James Straven’s life – the people, the sexual relationships, and the liberated lifestyle – which was completely at odds with the ‘buttoned-down Met Police existence’.

He was expecting to be sacked from the police and was building the Crossland identity as a backup.

FRAUDULENT USE OF DOCUMENTS

In addition to his illegal misuse of Kevin Crossland’s identity, Thomson obtained numerous passports in his ‘James Straven’ identity. He admits to removing pages from them to conceal unauthorised travel from his managers, which we explore in more detail in the section on Foreign Travel.

We were shown a report dated 8 March 2002 [MPS-0719569] which says that Thomson also had four driving licences in his ‘Straven’ identity. He accepts this. They are listed as the original, two replacements he obtained himself, and a fourth he asked the office to get.

The fourth licence is registered to the address of an activist, and an internal SDS debrief document explains the ruse [MPS-0722282]:

‘In conversation with the SDS office it was established that if his address was so remote that public transport was ineffective and he would be unemployable without a vehicle, a court would be disposed, under existing European guidelines, to merely fine him and put points on his (thus far clean) licence.

As a result a new licence was obtained showing JS resident at one of his weary’s addresses in deepest Sussex. This had the added benefit of having the ungodly involved in a small deceit against authority, which further enhanced JS’s legend.

Again the office was aware and seemed to agree it was a frightfully good wheeze. In the event the prosecution, like two before it, failed (more because JS, unlike JT, enjoyed the luck of the devil than because of any strategic thinking).’

From this it is clear that Thomson was prosecuted at least three times for traffic offences in his Straven identity, and supportive SDS management thought that committing fraud to deceive the courts was a ‘frightfully good wheeze’.

Another curious aspect of Thomson’s deployment is that, unlike most of the spycops we have heard about so far, he really did do the ‘cover job’, the employment he told activists that he had.

As James Straven, Thomson was a location finder for film and television. He actually gets credits in several productions, including the 1998 TV drama Coming Home, which starred Joanna Lumley and Peter O’Toole.

Throughout his deployment, Thomson was visiting his cover employment’s office one or two days a week. During filming, he would sometimes spend two full weeks on a set.

He says that he found the cover employment interesting. It included some travel, and he got to meet famous people like O’Toole and Lumley. It also meant he was receiving money over and above his overtime-inflated Metropolitan Police salary.

Thomson says he spent the wages he received from his cover employment in his ‘Straven’ identity. He had multiple credit cards and bank accounts, which he used for anything he would prefer his management not to know about.

The overall picture we are left with is of a deeply deceitful and duplicitous man who had significant criminal tendencies well before he started working for the SDS.

Abusive Relationships

Thomson has now admitted to conducting two deceitful sexual relationships while undercover. He acknowledges that neither of the women he deceived would have consented to have sex with him if they had known his true identity.

Spycop HN16 James Thomson, ‘James Straven’/ ‘Kevin Crossland’

Thomson says he was divorced when he was recruited into the SDS and was in a new ‘off and on’ relationship. He says that managers preferred ‘a stable background’, but that their investigation into the stability of his relationship was limited.

He and his partner went through short-term breakups that he did not report to his managers, although he was expected to do so. He was concerned they would terminate his deployment if they knew his real relationship was on the rocks.

Significantly, Thomson recalls speaking to a number of former undercover officers whilst he was working in the back office, preparing to deploy.

He was mentored by ex-undercover officer HN1 ‘Matt Rayner’. We heard from Liz Fuller in the Inquiry’s Tranche 2 hearings about how she was deceived into abusive sexual relationship by HN1.

Thomson claims HN1 never talked to him about sexual activity during deployments, but did give him advice on how to infiltrate animal rights activism:

‘He described them and their world quite accurately. He described sort of, I would say, the type of people… what was acceptable, what wasn’t.’

He was asked if he spoke to HN2 Andy Coles, who groomed a vulnerable teenager into a sexual relationship while he was undercover, and went on to author the notorious ‘SDS Tradecraft Manual’ [MPS-0527597]). Thomson says he cannot remember talking to Coles, but it is likely that he did.

Barr also asked Thomson about the Tradecraft Manual itself, which offers deeply unpleasant advice to officers about deceiving women into sex, and advocates ‘fleeting and disastrous relationships’.

Thomson says the manual was regularly consulted for meetings with deployed officers. This is in contrast to the claims of other officers who say they never saw it at all. However, Thomson says neither he nor anyone else ever discussed the passage on sexual relationships.

Thomson says he knew his contemporary HN14 Jim Boyling well. Boyling deceived at least three women in his target group into sexual relationships, before going on to have children with one of them. Thomson recalls ‘chatter’ within the SDS about the fact that Boyling’s partner, ‘Rosa’ was trying to find him after his deployment ended and had got hold of a phone number for the SDS office.

Thomson remembers speaking to his manager Bob Lambert about the work. But again, he claims these conversations were never about sex.

‘He was a Detective Inspector, as you said, so sort of more general advice as well. A lot more on the process, about how slow to take it and so on…

Lots of stuff about cover employment, back story. So what bits of legend work and don’t work, what that should look like…

Q. Any advice about how close to get to the activists you were seeking to report on?

A. I think as close as you could.’

Lambert’s earlier period as an undercover officer in the 1980s is one of the most controversial deployments. He gave evidence over seven days in 2024, including about how he deceived four women into sexual relationships, and fathered a child with ‘Jacqui’.

Lambert is expected to return to the Inquiry in 2026 to give evidence about his time as a manager of the SDS, including his oversight of Thomson.

The upshot of all this is that the newly recruited Thomson was introduced to the job by HN1, Coles, Boyling and Lambert, all of them known abusers.

It really brings it home that, by the late 1990s, the SDS resembled a predatory grooming gang, with the worst offenders being promoted and put in charge of initiating new members. It is therefore unsurprising that Thomson’s would become one of the most disturbing deployments to date.

THE RELATIONSHIP WITH SARA

‘Sara’ joined the Croydon hunt saboteurs in 1998. She met Thomson on one of her first hunts, in the autumn of that year. Her evidence is that Thomson asked her out to dinner.

‘Q. You got on well?

A. Yes.

Q. And you called her?

A. Mm-hm.

Q. What caused you to call her?

A. I can’t actually remember calling her. I don’t dispute that’s what happened.

Q. This is calling her to ask her out for dinner?

A. Mm-hm.’

This kind of evasive response is very common from officers like Thomson when they are asked about the details of their abusive behaviour. They don’t deny the facts, but neither do they properly admit them. It is dismissive and offensive. Their identical claims to have no memory of events (without disputing the woman’s account) are made so often and consistently that they lose all credibility.

Asked why he asked Sara out for dinner, Thomson replies:

‘Beyond the obvious attraction, various other things, my own psyche, loneliness, I don’t know… Sexual attraction, certainly…

Q. Can we take it this was done purely for your sexual gratification?

A. No, I think that’s unfair. I think it was a genuine relationship.’

Describing their abusive, deceitful and sexually exploitative behaviour as ‘genuine relationships’ is another offensive SDS trope we have seen time and time again. Like other sexually abusive officers at the Inquiry, Thomson has conceded that he understands that she would never have let him near her if she’d known who he was, and yet is unwilling to admit what that really means.

Thomson claims that he and Sara had a ‘strong connection’, although he also claims not to have known that she wanted the relationship to become long-term. He accepts that he saw Sara about twice a week, and that their relationship was well known within the small social circle they were moving in.

‘Q. You told her that you loved her in 1999, didn’t you?

A. I accept that…

Q. Why did you tell her that you loved her?

A. Because I did.

Q. There was an elephant in the room though, wasn’t there?

A. Certainly.

Q. You were not who you said you were?

A. Correct.

Q. You were a serving police officer?

A. Yes.

Q. On duty?

A. Yes.

Q. She wouldn’t have consented to the relationship or to sex if she had known who you really were, would she?

A. I think not. Sorry, I know not.’

Thomson seemed visibly uncomfortable during questioning about Sara. He gave mostly monosyllabic yes/no answers, not disputing Sara’s account but claiming not to remember or not to know what his thoughts and motivations were at the time.

He says he can’t remember telling Sara that his ex-partner had tricked him into having a child, but agrees that he probably said it because the ages of his children would have meant he had them very young.

This is because Thomson was lying to Sara about his age, claiming to be several years younger than he really was; another trait so common among SDS officers that it was surely training and tradecraft.

REPORTING ON SARA

The first mention of Sara in Thomson’s reporting is from March 1999 [MPS-0001923]. It is an intelligence report about an animal sanctuary that claims Sara works there part time, and Croydon hunt saboteurs are forging close ties with the sanctuary:

‘In the near future the entire sab group will be attending the sanctuary to assist in the construction of a duck pond.’

In addition to the total absurdity of a police intelligence report about a duck pond, Barr pointed out that the report is inaccurate. In fact, the only link between the sab group and the sanctuary was that Wendy and Sara were involved in both. Thomson reported Sara as being employed by the sanctuary, which wasn’t true.

‘Q. That’s not really close ties between the group and the sanctuary, is it? It is more the fact that two animal lovers are both hunt saboteurs and work at an animal sanctuary?

A. No, but it was a link across to the hunt saboteurs.

Q. “Sara” didn’t work there, did she?

A. No.

Q. So this information is wrong… Were you trying to place “Sara” at the sanctuary, making the connection with Croydon hunt saboteurs to justify reporting on “Sara” and spending time at the animal sanctuary?…

Doesn’t the phrase “entire sab group will be attending the sanctuary” overstate the position?…

A. Yes, I would agree with that.’

BREAKING UP WITH SARA, PARTIALLY

Sara’s account of the breakup of her relationship with Thomson was that he disappeared over the Christmas period in 1999. She couldn’t contact him for about two weeks.

He says he assumes he was with his family, and answered all further questions about the breakup with ‘I accept that’ whilst saying he cannot remember.

In fact, Thomson spun Sara a cruel story about experiences of childhood rape and sexual abuse that he used as an excuse to end the sexual relationship. Asked why he did that, he dismissively said:

‘That was in my legend anyway… The abuse and so on.’

Barr noted that there is no written record of any mention of child abuse in James Thomson’s legend.

Despite this, Thomson claims he’s sure it was not something he invented just to tell Sara. He insisted that his managers were fully aware that a history of child sexual abuse made up part of his false identity, and he remembers talking to Detective Sergeant Webb about it.

He says he cannot recall giving any thought to how any of this might affect Sara, and he tries to deny how manipulative it was.

‘Q. If it wasn’t highly manipulative, what was it?

A. I am not disputing that it wasn’t, I just didn’t see it like that. I saw it as a continuation of a genuine friendship.

Q. How could it be a genuine friendship when it was so deceitful from your side?

A. As I said, that was my perspective. I fully accept it can’t have been, and yet I believed it was.

Q. An extremely selfish way to behave?

A. Certainly.’

Thomson alternately claims that he cared about Sara whilst also admitting that he never thought about her feelings or how his behaviour might affect her. By now, he seems a lot less relaxed about the questions.

Thomson remained close to Sara and very shortly after their breakup, in early 2000, he travelled out to Goa, India to meet her there and visit an animal sanctuary. Again, he claims he has no memory of this:

‘I can’t remember it. I don’t dispute it might have happened.

Q. Assuming it happened, unauthorised?

A. I presume so.’

This is just one of many highly controversial trips abroad taken by Thomson which are dealt with below. Sara was also persuaded to join Thomson in France on holiday during what now turns out to have been the extraordinary ‘Operation Lime’ plan to fit up hunt sabs on firearms charges.

Sara moved abroad, and Thomson encouraged her to do so, giving no thought whatsoever to how he was influencing her important life choices. Thomson admits he stayed in contact with Sara by email long after she left the country.

We were also shown his phone’s call logs [MPS-0719722], which show 48 calls to Sara, who is described as the ‘ex-girlfriend of L1’. Thomson accepts Sara had never been L1’s girlfriend.

‘Q. Might it have been that you were deliberately trying to misrepresent events to throw managers off the scent of your own misconduct?

A. Entirely possible.’

Sara then became the focus of additional secret police attention. We were told that management documents exist that talk about ‘protecting’ Thomson from Sara, because she lived close to his ex-wife and children, and so there was a risk of her seeing him in his real life.

Thomson admits that he knew where Sara lived when he started the sexual relationship. He knew this put his deployment at risk and says it was stupidity that led him to put his sexual gratification ahead of basic security.

This is part of another pattern we have seen: entirely innocent people met SDS officers in their undercover roles and were then placed under intensive surveillance, simply because they lived near the officers’ real homes.

People were physically followed in order to establish patterns in their lives. There is evidence that attempts were made to influence where they lived (for example Wendy’s house purchase, examined below).

THE RELATIONSHIP WITH WENDY

The first of Thomson’s intelligence reports to mention Wendy is dated 22 August 1998 and refers to the Old Burstow Hunt’s first cubbing meeting of the 1998-1999 season [MPS-0247867].

Wendy gave live evidence to the Inquiry on 23 October 2025, during which she made clear that she is sure she met Thomson long before the Old Burstow Hunt event.

Thomson accepts that he met her early in his deployment, in 1997, when she was just 17 years old and lived at home with her mother. He became part of her intimate circle of friends, but tries to play their relationship down in his evidence:

‘Q. You became very close friends, didn’t you?

A. We were certainly friends, yes…

Q. To say that you were a close associate would be to understate the position, the reality was you were very close friends?

A. In which case I will accept that.’

In fact, Thomson supported Wendy during her mother’s long illness and death. Thomson says he can’t remember that, although he added:

‘I accept that if I had that opportunity I would have taken it, yes…

Q. You don’t remember the protracted course of somebody dying who is close to one of the people you are mixing with?

A. No.

Q. Why do you think that is?

A. I don’t know.

Q. Is it because you just didn’t care?

A. I hope not.’

Thomson also advised Wendy to split up with her then-boyfriend.

YOU WEREN’T MEANT TO FIND OUT

We were shown an intelligence report where Thomson mentions that breakup, along with the personal lives and sexuality of several members of the Croydon hunt sab group, in flippant and disrespectful terms [MPS-0003413].

Thomson defended the deeply personal nature of the reporting:

‘As I say, I reported anything. They were obviously always intended for the very small audience anyway, and certainly not for the subject to ever read it. So I can only apologise for that.

Q. Was there generally a culture of being disparaging about activists?

A. Yes, I suppose that’s fair.’

Wendy encouraged Sara, and later Ellie, to have relationships with this man who she believed was her good friend. She also recalls a number of instances where Thomson tried to create a sexual frisson in his relationship with her. Thomson denies this but adds ‘there’s lots of things I can’t see myself doing that I have done.’

Spycop HN16 James Thomson

He is asked whether he is trying to claim Wendy posed a physical threat or was a violent activist. Thomson says no, but then claims that ‘she had a temper and she was a committed activist’. His evidence in this section was frankly all over the place.

The most shocking evidence we heard about Thomson’s friendship with Wendy concerned the fact that, after her mother died, she bought a house very close to where Thomson’s ex-wife and children lived. We were shown a management document [MPS-0719701] which refers to ‘attempts to disrupt this purchase having failed’.

Thomson claims not to remember what he and his managers did. He is sure he tried to put her off, though he claims this was limited to telling her there were better areas to live.

However, Wendy recalls significant issues with probate. Her solicitor told her probate sometimes took up to six months, but with her mother’s simple uncontested will it would be much swifter. But it took six months to the day. She nearly lost the home she’d set her heart on.

This all indicates that the SDS actually tried to interfere with the will and the house-buying process.

THE RELATIONSHIP WITH ELLIE

Thomson started a relationship with Ellie very soon after Sara moved abroad.

Ellie wasn’t an animal rights activist, she was a friend of Wendy’s who worked at the same animal sanctuary. Thomson asked Wendy to set them up.

Again, he claims he can’t remember that, but he accepts it. Ellie was 21 at the time. Thomson told her he was 33. In fact he was 37.

‘Q. For a 37-year-old serving police officer undercover to initiate a sexual relationship with a 21-year old woman is an aggravating feature of your deception of her, isn’t it?

A. Yes…

Q. A very conscious deception of “Ellie” as to your real age?

A. Yes, it was all a deception.’

Thomson’s replies became quite petulant and defensive during Barr’s questioning about Ellie.

Asked why he started a sexual relationship with her, Thomson replied:

‘I don’t know that I did start a sexual relationship with “Ellie”. I think I started a relationship that became sexual, which is not quite the same thing.

Q. Why did you start an intimate relationship with “Ellie”?

A. I liked her. I liked her.

Q. So, again, your own sexual gratification?

A. In amongst the other parts of “like”, yes.’

At the time, Ellie had lost her job following sexual harassment by her boss. She was homeless, and unemployed.

‘Q. To take advantage sexually of a woman who was not only vastly younger than you, but also vulnerable, young and naive was a further aggravating feature of your deception of “Ellie”, wasn’t it?

A. I agree that it was. I am not sure I saw her as vulnerable.

Q. Is that because you really weren’t thinking about her feelings at all?

A. Entirely possible.

Q. Thinking entirely about yourself and your own sexual gratification?

A. Yes. I don’t like the word “entirely”, but I won’t dispute it.’

Thomson was Ellie’s first boyfriend and her first love. He accepts that he knew that. She thought it was a committed monogamous relationship, but he was actually in a relationship with someone else. Thomson did not use condoms and he got Ellie to use to use other contraception to avoid pregnancy.

Barr asked Thomson about his use of ‘mirroring’ – reflecting a person’s interests, feelings and personality back at them in order to make them feel a connection – and other manipulation of Ellie, to which Thomson replied:

‘You are reading a lot into it. I don’t think that’s fair.’

Yet all these elements are strikingly similar to how other women had been deceived by earlier SDS officers who were Thomson’s superiors. Identifying a vulnerable, much younger woman, and then grooming her into a relationship is exactly what Bob Lambert had done with Jacqui, and Andy Coles with Jessica. As with the lying about age, it seems too much of a coincidence.

Thomson took Ellie on holiday to Indonesia and Singapore during another of his unauthorised trips abroad, which are examined in more detail below.

BREAKING UP WITH ELLIE, PARTIALLY

Ellie had been with Thomson for about ten months when he told her, in January 2002, that he had to move to the United States because his ex-wife and children were moving there.

That was supposed to be part of a longer exit strategy from his deployment, but Thomson’s managers had, by then, begun to uncover the extent of his extensive fraud and other misconduct, and his deployment was brought to a rapid end.

Thomson had to tell Ellie he was leaving sooner than expected, and he pretended to leave the UK in March 2002. He maintained the sexual relationship right up until he supposedly left. He accepts that there was no real ending of the relationship, because he immediately began to deliberately lay the ground for it to continue.

‘Q. You didn’t want your deployment to end, did you?

A. I didn’t.

Q. And you were a man who ignored your managers when you didn’t like what they had to say, and you were going to stay in touch with “Ellie” despite being withdrawn, weren’t you?

A. Yes.’

HARASSMENT AND MANIPULATION AFTER HIS DEPLOYMENT ENDED

Thomson remained in contact with both Ellie and Wendy for sixteen years after his deployment ended, from 2002 to 2018, by email, phone and meeting up in person. This continued even after the spycops scandal broke and after the Undercover Policing Inquiry had been announced.

We were shown an email to Wendy that he sent on 30 March 2014 [UCPI0000038209]. In it he lies about his life, claiming to be in Canada and returning home to LA (in fact he was still a police officer, living in London). He says he is in an airport sat opposite the Victoria’s Secret store watching rolling adverts of women in lingerie for hours:

‘Let me know if you think that’s sad at all won’t you – even I might get a little jaded by the time I fly’

His regular emails asked about her life and the other activists he had targeted while undercover. He claims that this was ‘just because they were people I knew and had liked.’

Thomson says he doesn’t know if he would have ever ended his contact with Ellie and Wendy if his real identity hadn’t been exposed. He admits that his conduct was extremely harmful and unnecessary.

In her appearance at the Inquiry two weeks before Thomson’s, Ellie gave detailed evidence about the ongoing contact.

Thomson claims not to remember details, but does not dispute anything Ellie has said. He admits he always enjoyed seeing her, and they were ‘like a couple’. He accepts that he prolonged the romantic relationship, picking up where they had left off.

Spycop James Thomson with Ellie at the Raffles Hotel, Singapore. He’d travelled there against the instructions of his managers.

We were then shown some of his emails to her. Barr systematically went through the sexualised comments, including repeated references to sexual frustration, to ‘drooling’ about her ‘in entirely inappropriate ways’, references to a ‘uniform fetish’, and Thomson fantasising about Ellie naked in his office – which is particularly worrying considering where he worked.

We saw an email from October 2011 that is very heavy emotionally and includes him complaining about how sexually frustrated he was, having recently seen her but not had sex.

It is remarkable that he was still sending these emails even after spycop EN12 Mark Kennedy had been uncovered and the scandal of undercover relationships was front page news. Thomson says he didn’t make a connection between himself and these things.

In another email, dated 13 September 2011, Thomson asked Ellie to send photos of herself in lingerie to help with his sexual frustration. Thomson tries to claim he was not being serious, and yet he repeated it in later emails. He claims the persistent requests were not pressurising her, and tries to characterise it as a ‘running joke’.

He often projected their relationship into the future, describing how it will be fun to meet up when Ellie is ‘old and grey’, and he is ‘a ghost’. He admits that he was stringing her along.

Ellie has said that she never got over the relationship with ‘James Straven’, because real men couldn’t measure up to his fabricated persona. He accepts he manipulated her emotions, and affected her ability to have real world relationships.

On 24 June 2015, Thomson met up with Ellie and they did have sex. It is pointed out that this sex with Ellie was soon after the start of the Inquiry. He, incredibly, claims that in his mind he did not connect the two things.

In December 2017, the Inquiry ruled that it would release Thomson’s cover name, ‘James Straven’. In 2018, Thomson finally told Ellie that he was an undercover officer. He didn’t tell her his real name during the call. He didn’t apologise.

He now says he didn’t realise that he hadn’t apologised. He says he never gave Ellie ‘the right sort’ of thought at all, and never once considered her feelings, because his conduct has always been directed by his own self-interest.

This extreme self-centred thinking, not just during deployments but afterwards, is yet another running theme among spycops officers.

Targeting and deployment

INFILTRATING THE HUNT SABS

It is notable that although Thomson was initially deployed into the Brixton hunt saboteurs, most of his infiltration was into the Croydon hunt sabs. He sought to defend that in his evidence by claiming they were more or less one and the same:

‘The organisational end was the Croydon bit by that time. Brixton hunt saboteurs sort of turned up.

Q. Would it be fair then in the light of that answer to say that you deployed into both Brixton and Croydon hunt saboteurs from the outset, or was there a progression from Brixton to Croydon?

A. I can’t remember the exact order, but certainly it was close.’

However, he went on to differentiate between the two groups, claiming that Brixton hunt sabs were more likely to attack the hunters, whereas Croydon would focus on saving the fox.

‘Brixton would sort of kind of turn up for the ruckus and they would tend to go towards hunt supporters and the people running the hunt and the hunt itself…

Insult them, spit at them, try and get people off horses. Try and basically start a confrontation. Just encourage and then join in a fight.’

However, when asked exactly how the sabs would get people off their horses, it became clear that this was more like an act of self-defence against mounted attackers with whips:

‘If they tried to swing a crop, obviously that gave an opportunity to grab that and pull and so on.’

In fact, Thomson accepted that he only ever witnessed minor criminal damage and minor assaults by hunt sabs. Barr says he gets the impression it was more a question of goading by sabs and violence by hunters:

‘Q. Did you see hunt saboteurs throwing the first punch?

A. I am not sure. I can’t remember a specific incidence of that.’

Thomson also said that sabbing got more violent over the course of his deployment. Again, he was asked who would have committed the first violent acts in that escalation:

‘I wouldn’t like to say. I think I am probably biased, because I would say the hunt were more likely to, and I was on the other side.’

We were shown his first report, dated 22 February 1997, about upcoming animal rights protests [MPS-0000168]. He said he doesn’t know if the information in his first report was publicly available or not, but he accepts that at that stage, his infiltration was limited:

‘I would have turned up at a couple of sabs’.

Barr points out that this demonstrates that a very superficial shallow infiltration was all that was needed to get that kind of information.

GOING DEEPER

In May 1997, a file note [MPS-0247080] written by his manager HN10 Bob Lambert, just four months into Thomson’s deployment, recorded that:

‘The activists seem to have been impressed by [Thomson’s] ability to handle himself and face up to violent threats from hunt supporters and the like.’

Thomson agreed that this is probably accurate, although again, he cannot recall a specific incident.

Thomson claims that he doesn’t remember ever being known by the nicknames ‘Posh Sab’ or ‘James Blonde’ whilst he was deployed.

He claims he ‘would have noticed’. All the civilian witnesses he spied on insist that they remember calling him these names to his face.

The May 1997 file note also describes:

‘On Monday, 5 May he received his first in-depth grilling from his new associates. He appears to have handled this well.’

Asked about this, Thomson says:

‘It was a back room in a pub in south London. And just lots and lots of questions… My interest, vegetarianism, veganism, a little bit about where I had been, why I hadn’t been on sabs before.

That sort of thing…Q. As to the demeanour, were these threatening questions or were they just gentle inquisition?

A. I felt slightly under pressure, as far as I can recall. I didn’t feel physically at risk. I wasn’t looking at the windows or anything that I can remember…

Q. If you had not satisfied your questioners, what do you think would have happened?… Was your feeling that you would have been under any physical threat?

A. Yes. They were naturally violent, or some of them, to be fair. Some of them were naturally violent…

Q. Might that have been a subjective fear rather than one with an objective basis?

A. Absolutely.’

One spycop after another infiltrated hunt sabs and described them as seriously violent. Under examination, none of the officers can cite any instances, but vividly describe serious violence from hunters and supporters. HN2 Andy Coles even wrote in the SDS Tradecraft Manual [MPS-0527597]:

‘I know that in the future I will have nothing but contempt for fox hunters and in particular their terriermen.’

Despite all this, the SDS did not infiltrate hunts, and even now they insist that sabs were a deserving target for spying. This proves that the SDS wasn’t focused on the risk of violence and disorder, but rather on threats to established social hierarchies.

ACTUAL DANGER AND VIOLENCE

We were then shown an SDS memo dated 8 August 1997 [MPS-0247206] which records that Thomson was in fact hospitalised in his cover identity on 10 July 1997, with a fractured collar bone and jaw.

Spycop HN2 Andy Coles describing his ‘contempt for terriermen’ in the SDS Tradecraft Manual

But it was not the hunt sabs who caused those injuries: he was attacked by hunt supporters on a Countryside Alliance march.

Asked about the incident, he says his managers were sympathetic. However, Thomson himself cannot remember how it happened as he was concussed and suffered amnesia.

This was not the only instance where Thomson was injured. A file note dated 21 November 1998 [MPS-0001577] records serious injuries to Thomson’s jaw, back and legs after being attacked by hunt supporters with golf clubs when sabotaging a hunt in Kent.

Thomson claims he cannot remember who else was there when he was attacked. The file states that the attack left Thomson:

‘in cheerful mood and upbeat about his increased credibility.’

A further injury report was filed on 18 November 1999 [MPS-0002618], when Thomson slipped a disc, which made it harder for him to participate in sabbing. He said it slowed him down.

Despite the SDS’s own files showing overwhelming evidence of violence coming predominantly from the hunters, we were shown an intelligence report from 4 August 1997 [MPS-0000483] in which Thomson claims southern England hunt sab groups had ‘hard reputations’.

Questioned about it, he admits that numerically there would almost invariably been far more hunt supporters than sabs. He further admits that it was common for sabs to be unfairly arrested by police:

‘I don’t know what powers they were using. You would be sort of stuck somewhere and quite likely released once the hunt had finished or gone.’

The report claimed that saboteurs were being asked to wear similar black clothing to make identification and post-hunt arrests more difficult. However, Thomson said he was never asked to help identify sabs from photographs, even if there had been incidents of violence, stating:

‘I was there for intelligence, not evidence.’

We were then shown a series of Thomson’s reports from the 1998-1999 hunt season. One report from 23 March 1998 [MPS-0000959] describes the hunt supporters coming off ‘second best’ to the sabs and being attacked while they hid with the police.

Barr was obviously quite struck by this report:

‘Wouldn’t that have been quite a striking and memorable incident.. one which certainly, as depicted here, is violence perpetrated by hunt saboteurs that goes well beyond lawful self-defence?’

Thomson seemed unimpressed, and claims to have no memory of the incident. Despite this, he denies any possibility that he might have exaggerated his report:

‘If I have reported it, then it happened.’

Given the fantastical nature of such a lot of SDS reporting (including the staggering claims made by Thomson about Operation Lime) this statement is meaningless in terms of establishing historical accuracy. Nonetheless, it offers an interesting insight into the SDS mindset and the way they approached intelligence: if we reported it, then it happened (and not the other way around).

MORE NON-SPECIFIC ALLEGATIONS OF VIOLENCE

Another report, which is undated but which the Inquiry has placed within this period, refers to Croydon hunt sabs supposedly planning an attack on a local fascist [MPS-0001541]. Barr points out this is an unusual report:

‘It is not about animal rights, is it? It’s about an alleged plot by the Croydon hunt saboteurs physically to attack a man for his far, or perceived far, right political views…

Did that actually happen?… Why would the Croydon hunt saboteurs, an animal rights group, plan an attack on a fascist?’

Thomson is characteristically vague in his responses, claiming that sabs were very anarchic and that:

‘The right wing were the enemy… across sabbing and animal rights generally.’

He claims he cannot remember whether anything came of the supposed plan. He accepts that if a man had been attacked he would have reported it, but then immediately adds more vague allegations of the same kind:

‘I mean attacks in that area did happen, especially after drink. But they tended to be spontaneous ones.’

The justification for Thomson’s spying on the hunt sabs seems tenuous at best. By then, hunting was on the way to being made illegal, and we saw notes from a strategy meeting dated 2 January 2000 [MPS-0003394]:

‘Sabbing will remain an important area, particularly as the ground is prepared for the anti-hunt bill to be presented in Parliament.’

Barr then showed us a document claiming that Thomson had close contact with activists from the Animal Liberation Front (ALF). The ALF was one of the SDS’s main bogeymen at the time, regarded as the most extreme tier of animal rights activism.

Protest at Shamrock Farm monkey breeding facility

The document is a file note dated 22 May 2000 [MPS-0003403], signed by HN58, the Detective Chief Inspector in charge of the SDS 1997-2001. It refers to Thomson ‘having forged close links with active ALF types.’

However, there is no real evidence to suggest Thomson ever had any links to the ALF, only to the Croydon hunt sabs.

It appears to be another example of the spycops exaggerating their work to the managers, then the managers exaggerating further, an effect repeated as the information went up the chain of intelligence to the higher echelons of the police and Home Office.

Indeed, not only were there no reports from Thomson about the ALF but also, Barr pointed out, the Inquiry actually has very little reporting from Thomson at all in this period.

Asked how much sabbing he actually did in the 2000-2001 and 2001-2002 hunting seasons, Thomson replies:

‘A. I don’t think there was any drop off particularly…

Q. There is reporting about the injury suffered by L4 and responses to that which we will be coming to in due course. But we do not see, as we have done to date, a stream of reporting about hunt sabotage.’

It appears, from the evidence, that Thomson’s decreased reporting about sabbing events may have been due to the changing relationship between the SDS and a new spycop unit, the NPOIU, which we will look at in more detail below.

SHAMROCK FARM

We saw significant reporting by Thomson throughout 1999 about the campaign against Shamrock Farm monkey breeders, Europe’s largest supplier of primates for vivisection.

Thomson reported on large, public and ‘fairly orderly’ demonstrations near the farm, describing them as ‘fairly well, if not heavily, policed.’

His reports also mention ‘home visits’, with activists protesting at the homes of people who owned Shamrock Farm, informing their neighbours of who they lived near. Thomson said he attended a lot of them.

It was put to him that, at the time, home visits could have been legal, but he disputed that fact:

‘The objective was to frighten the people there, or their associates, to make them in turn stop doing what they were doing, or drop the links they had to whichever company it was, depending on the association.

Q. What is the basis for your saying that the intention was to frighten, as opposed to make a point and disagree with what that person was doing by way of legitimate process?

A. I suppose that’s how I remember it.’

In fact, there was no law preventing these kinds of protests until the Criminal Justice & Police Act 2001, something which Thomson, as a serving policing officer working in the animal rights field, really ought to have been aware of.

Thomson’s claim that the aim of the visits was ‘intimidation’ is further undermined by the fact that, despite saying he had attended many of them, he could only recall one instance of criminal damage (a broken window) and one instance where there was an altercation with a neighbour of the targeted house.

It was clear from the documents we saw that, although Thomson was taking part in the actions, he didn’t actually report much specific or pre-emptive intelligence about these protests at all.

Shamrock Farm closed down in 2000. Barr commented:

‘Whether or not that was because of the campaigning may be a separate question… there was some suggestion it may have been because of financial improprieties at Shamrock Farm, but there is another report… [MPS-0003412] dated 25 May 2000.

It says a person, whose name we are protecting, “has discovered, through an employee of the firm, that the arson on [privacy]’s garage was the final ‘straw’ that led to the closure of the premises”.’

It says a lot about the questionable quality of the SDS intelligence we have seen over the past five years of this Inquiry that Barr’s next question was:

‘Do you know whether or not that in fact occurred?’

Thomson can’t remember, and there are no intelligence reports about such an incident. So, Thomson was deep undercover, spying on the Shamrock Farm campaign, but is unable to provide any useful information at all about an arson attack that he alleges got the place closed down. It’s simply not believable.

THE GROWING REMIT OF THE NPOIU

We saw a file note about targeting strategy which recorded a meeting between Thomson and Lambert dated 30 January 1998 [MPS-0247069].

It explores an out-of-London tasking, specifically going down to Hastings, which it describes as ‘an emerging centre of ALF activity’.

Thomson was asked whether there was there any boundary drawn between the Metropolitan Police district and out-of-area activities:

‘Not that I can ever remember, no.

Q. Was a matter of geography ever raised by your managers with you?

A. No… When you say “matter of geography”, I think at the very end of my deployment that was raised, but not at this point.’

Thomson was not specific about what he meant by saying it was raised at the end of his deployment. However, it seems it may well be to do with the formation of a new undercover policing unit.

The National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU) was established in 1999, using undercover officers in the same way as the SDS, and targeting the same sort of activities. But unlike the SDS, who, as a Met unit, were restricted to London, the NPOIU had a national remit.

There was a sizeable degree of crossover between the two units. It’s established that SDS Tradecraft Manual author HN2 Andy Coles trained the early NPOIU recruits, and there’s a mysterious gap in HN10 Bob Lambert’s CV at exactly that time.

A file note dated 22 May 2000 [MPS-0003403] reviewing Thomson’s operation states:

‘In view of NPOIU’s ever-expanding remit it is becoming increasingly difficult for SDS to operate effectively outside London on anything other than an occasional basis.’

Most, if not all, fox hunts would have taken place outside of the Metropolitan Police district, and Thomson’s decreased participation in and reporting on hunt sabbing from 2000-2002 may well have been related to that as much as his slipped disc.

Thomson claims not to know about this:

‘I was aware of them. But clearly there is something else going on in terms of who is responsible for what there that I wasn’t really cognisant of.

Q. Was there a feeling, that you were aware of, of the SDS’s work being encroached upon by the National Public Order Intelligence Unit?

A. Not that I can ever remember feeling…

Q. Did you have any direct contact with the National Public Order Intelligence Unit?

A. No.’

SDS AND NPOIU CROSSOVER

There are a number of SDS reports made on NPOIU forms. For example, in November 2025, during the Inquiry’s questioning of trade unionist Frank Smith, we saw that SDS spycop HN104 Carlo Soracci ‘Carlo Neri’ had filed a report on 29 January 2002 on NPOIU forms [MPS-0007725].

Report filed by SDS officer Carlo Soracchi on NPOIU forms, 29 January 2002

It’s unclear whether this was actually the NPOIU also spying on Smith, or whether Soracchi was using their forms for some reason.

Either way, it shows a significant degree of overlap between the two units.

Thomson was also asked about the earlier relationship between the SDS and the Animal Rights National Index (ARNI, which was later subsumed into the NPOIU), specifically whether ARNI was a customer for SDS intelligence. Yet again he was vague and said it didn’t really come up.

However, the impact of that relationship was certainly greater than Thomson is letting on.

Because of the changing remits and the growing role of the NPOIU, SDS manager HN58 suggested that Thomson should begin looking at a withdrawal strategy in May 2000, with early 2001 as a finish date for his deployment (this may be what Thomson meant by the matter of geography coming up at the end).

‘Q. You are recorded as expressing some disappointment at that, and the reasons are then set out.

Is it right that you were disappointed at the prospect of ending your deployment in early 2001?A. Yes, I am sure it was.

Q. Is that something you felt really pretty strongly about?

A. I suspect so, yes.

Q. Would it be fair to say that your cooperation with this plan was rather begrudging?

A. Yes, I imagine so.’

Thomson’s resistance to the plan to shut down his operation in early 2001, and his desperation to find an excuse to continue, form the backdrop for what subsequently became Operation Lime: his trip to France with a bizarre plot alleging hunt sabs were buying a gun.

Participation in Crime

Asked about participation in crime, Thomson says his manager HN10 Bob Lambert spoke to him about this:

‘We certainly discussed the reporting of it, how that was managed, advance information. We discussed some sort of bits on spontaneous violence and how you deal with them…

Q. Did you discuss the gravity of offence that you might become involved in?

A. Certainly as a relative thing, i.e. you’re there to prevent and mitigate harm. So that’s what you do. In terms of is there an absolute limit, no, I think that was always part of the context.

Q. Were you told that you needed to get advance authority to participate in crime?

A. I was certainly aware of that where possible, yes.

Q. And where not possible?

A. Then you prevent harm, report later.’

Thomson described the process for getting authority to participate in crime:

‘I think I would always have expected it starts with a conversation with the person who is handling you and then they will then decide what sort of level authority it might need.’

Barr pointed out that there is no evidence of a paper trail or any prior authority for any of the crimes Thomson was involved in, with the exception of Operation Lime, which we look at below.

Thomson claimed that he and Lambert did not discuss any specific examples, but that these conversations about participation in crime made up a significant part of the conversations he had with Lambert.

‘I think we discussed scenarios, rather than examples…

What would you do if the group you’re with see someone and decide to attack them, for example. What would you do if they suddenly decide they are going to commit an arson, et cetera.’

This is obviously significant as Lambert himself is accused of having organised and participated in arson attacks against Debenhams department stores. Sadly, Thomson was silent on exactly what Lambert said he should do if his group decided to commit arson.

Barr also asked whether the Home Office guidelines on participation in crime [MPS-0727104] formed the basis for Thomson’s discussions with Detective Inspector Lambert, to which Thomson replied ‘I am sure they were. I am sure they were,’ before admitting:

‘I am not that familiar with them, I can’t remember ever actually looking at that at the time.’

The guidelines expressly forbid misleading courts, though Thomson not only did this but had his managers’ blessing too.

PUBLIC DISORDER

The evidence is that Thomson participated in crime on multiple occasions. We were shown an intelligence report from 12 April 1997 [MPS-0000303] about the March For Social Justice, which Thomson attended with the hunt sab groups he had infiltrated.

The report describes some serious public disorder, and Barr asked him about that:

‘Q. Were you anywhere near that public disorder?

A. I assume so.

Q. What do you recall of it?

A. I can’t recall anything specific. There were a lot of these at that time. Not necessarily labelled March For Social Justice, but serious public disorder in central London…

Q. Were any of the people who you were attending this demonstration with violent?

A. Yes.

Q. On this occasion?

A. I don’t know about this occasion.

Q. Are you able to help us with whether any of them broke the law on this occasion?

A. No, not specifically this occasion. I couldn’t say that.’

These kinds of generalised allegations of serious criminality, violence or disorder without being able to offer any specifics is typical of SDS evidence, and came up very frequently during Thomson’s oral evidence.

While Thomson didn’t know if he was disorderly or not on the March For Social Justice, he says he was active in disorder in ‘these sorts of events’:

‘Q. As a matter of generality, how disorderly were you at this sort of event?

A. I was certainly active… obviously I had been the other side of the shields sort of thing, so I knew that you could go and kick a shield for as long as you like and it didn’t do any harm. So that sort of thing, I would certainly have done that. Yeah, I suppose I just worked within those sort of limits.

Q. In order to demonstrate your activist credentials, how forward were you in this activity?

A. I would have been in and amongst.

Q. Would you be the first to kick the shield?

A. No, I don’t think I would ever have been the first.

Q. Amongst the first?

A. Amongst the first is probably fair.’

We were then shown a file note written by Lambert from 6 May 1997 [MPS-0247080], about the March For Social Justice and a protest at Consort Beagles in Ross on Wye, a breeder of dogs for vivisection, where Thomson was injured by riot police.

In it, Lambert refers to the Consort Beagles protest as ‘an ALF demo’.

As we saw with SDS manager HN58’s reference to Thomson having close contact with the Animal Liberation Front, this seems to be another instance of management exaggerating Thomson’s activity, upgrading him from hunt sab to a group viewed as more dangerous.

Asked about the difference between an animal rights demo and an ALF demo, Thomson replies:

‘I don’t know that there is one. I suspect ALF is a bit of a shorthand.’

This confirms what we saw in evidence in the Inquiry’s Tranche 2 hearings, that the SDS used the term ‘ALF’ as a catch-all, leading to sloppy and inaccurate reporting that sought to justify spying on everyone and anyone with an interest in animal rights.

HUNT SAB ‘MASS HIT’

Thomson was also questioned about an incident on 13 December 1997, about a ‘mass hit’ against a hunt.

A ‘mass hit’ was when one hunt sab group called for others from further afield to come and join them. They often happened after an incident of extreme violence by hunters, as a way of showing that sabs would not be easily cowed, and to discourage hunters from violence in future because it only made sabbing increase.

A report [MPS-0000736] described hunters’ cars being damaged and a fight with hunt supporters. Thomson accepts that he was there but he can’t recall much, nor give any real reason why he was there:

‘My mental image is actually the windows. That’s why I think I was there, I have got a mental image of the breaking of windows, car windows. And after that I sort of am in it and wouldn’t be able to sort of look up…

Q. When you say words to the effect you had your head down after the first window was smashed or words to that effect, was that because you were participating in this affray?

A. I was there.

Q. Were you participating in any of the violence against property?

A. Not that I can remember, no. I don’t believe so…

Q. At an event like this, what did you see your role as being?

A. To the extent I had a role, a useful role at all by that stage, just mitigate harm to the extent I could…

Q. You have seen the report. It is a long report, but it doesn’t identify any individuals, does it?

A. Mm-hm. No, it doesn’t.

Q. Can you recall whether or not you did intervene to mitigate the criminality that was ongoing?

A. I can’t.’

ARRESTING THE SPYCOP

Thomson was arrested on 29 August 1998, for obstructing police, as part of a sit-down protest on the A1 near Huntingdon Life Sciences vivisection facility. He was bailed but ultimately not required to return.

Protest agasint Huntingdon Life Sciences vivisection laboratories

Minutes from an SDS strategy meeting from 27 January 2000 [MPS-0003394] refer to the Mayday 2000 protests organised by Reclaim the Streets, which Thomson attended.

He claims that members of the group he was with took part in physical violence that day, fighting with the police in Whitehall. But, yet again, he can’t make an allegation of any specific violent act.

He claims he reported it at the time, but there is no sign of that report.

Thomson admits that he provided night vision equipment to the sabs, and that his intention was that it would be used for illegal activity.

‘Q. So you were facilitating crime?

A. I accept that.’

He defended providing the equipment, claiming doing so would improve his credibility with the group. In fact, the sabs mostly used it for wildlife watching at night.

Thomson also admits to committing criminal damage by destroying badger traps on a regular basis. He says his SDS managers were aware of this and content for him to do it.

However, the most extreme instance of Thomson’s managers allowing him to participate in crime is the story of ‘Operation Lime’.

OPERATION LIME – THE GUNPOWDER PLOT

Operation Lime is an astonishingly complicated police plot which eventually involved Thomson travelling in his cover identity to Turkey, Indonesia, Singapore and twice to France, ostensibly as part of a conspiracy to acquire a firearm, ammunition and (inexplicably) a bag of ‘black powder’.

![Police photograph of the gun found in James Thomson's car, January 2001 [MPS-0004963]](https://campaignopposingpolicesurveillance.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/L3-gun-MPS-0004963-scaled.jpg)

Police photograph of the gun found in James Thomson’s car, January 2001 [MPS-0004963]

The beginnings of Operation Lime came shortly after Thomson was told, in May 2000, that his deployment would be brought to an end by early 2001. It was recorded at the time that he was very unhappy about that decision. It seems he came up with the gun plot as a way to extend his deployment.

On 1 September 2000, a member of the Croydon hunt sabs, known in the Inquiry as ‘L4’, who Thomson had befriended during his deployment, was almost killed by a hunt supporter who ran him over with a Land Rover.

Thomson was not there when it happened, however he filed a report that same day [MPS-0003867] which claimed:

‘There has been immediate talk of reprisals, but no definite plan has yet been formulated.’

Barr asked him who was talking of reprisals at that stage:

‘I can’t remember who I spoke to. I think everyone. It was a truly shocking thing… I mean everyone was very, very angry…

Q. But no indication that that anger would translate at that stage into action?

A. No.’

There was a demonstration at the hunt’s kennels the following day, 2 September, and another a few days later on 6 September. Barr went over Thomson’s reports about those events.

‘Q. I am not asking whether it had completely finished the saga, but was your impression that there had been a venting of anger?

A. No, I don’t think so.’

THE FRENCH CONNECTION

We were then shown a report entitled ‘The French Connection’ dated 31 October 2000 [MPS-0004388]. It is about a plot to obtain a firearm and a strategy to disrupt it.

‘Q. Is it right that your managers’ belief that there was a plot to obtain a firearm was the result of your telling them that?

A. I would presume so, yes…

Q. Were you ever told there was any other source?

A. No.’

The sole source of information about this uncorroborated plot was therefore, at all times, the word of Thomson himself.

The ‘French Connection’ report says the objective is:

‘to gain intelligence on the activities of L2 or L3 … leading to their arrest or disruption, without compromising the source and other long-term SDS operations. A requirement for source to give evidence in court will lead to compromise.’

On the same day, 31 October 2000, HN58 the Detective Chief Inspector then in charge of the SDS, sent a minute to the Commander Special Branch recommending disrupting or frustrating of the plot, rather than making arrests. He also requests authority for Thomson to take part in what is described as a ‘dry run’.

The resulting plan was absurdly convoluted. The police decided to allow the supposed purchase of a gun to take place, on foreign soil. The plan described:

‘a possible opportunity to disrupt in France. Having discussed with MT [‘Magenta Triangle’, code name for Thomson], the theft of his vehicle with ordnance inside could be engineered. This would take the ordnance away from the conspirators and severely disrupt any future plans.

The problem with this scheme is that Roger Pearce probably could not authorise it, particularly as the substantive ‘offences’ are taking place in France.

However, MT feels confident he that he could engineer a position whereby his vehicle could be “stolen”.’

The police plan for Operation Lime included the following steps:

‘MT + Companion depart for France

MT picks up ordnance and secretes in car

MT books into hotel or goes to restaurant

Vehicle gets stolen and ordnance removed’

There are further steps to the plan, but they have been redacted. The Inquiry has not said why.

A PLOT WITHOUT PLOTTERS

The detail of the police’s plan is quite striking. Firstly, because the document suggests that it is Thomson himself who is acquiring the ‘ordnance’, the activists seem to play little or no role. Secondly, because the document asserts that the activists have not actually planned anything:

‘Nothing has been planned so far; the intelligence has come from a number of conversations between interested parties.’

Barr asked Thomson to clarify:

‘In the period between 1 September 2000, when L4 was run over, and 31 October when this document is generated, what conversations had been held between which interested parties?’

Thomson pointed to L2, L3 and himself, but hedged his bets about whether anyone else was involved.

‘Q. Just the three of you?

A. I can’t say that exclusively.

Q. Well, who else?

A. I don’t know…

Q. It is quite a big deal, conspiring to either shoot or murder somebody, isn’t it?

A. Of course.

Q. And one would be pretty careful about who one entered into a conspiracy with to do that?

A. Certainly.

Q. Is it really the case that you are not sure who was party to the conspiracy at this stage?

A. I only know the people I was talking to.’

It was very noticeable that Barr wanted concrete details about who, where and how the plot came into being, while Thomson seemed to be intentionally vague.

A NEW CONSPIRATOR

It seemed that Thomson was making up this gun plot as he went along, and there were audible laughs from the public gallery as he failed to answer any of Barr’s direct questions.

He eventually, begrudgingly, named four people: L1, L2, L3, and a fourth person who had not been previously mentioned at all. They have now been ciphered as L6.

Like L3, L6 had no part in this Inquiry until Thomson suddenly named him in his evidence. L6 has since made a written witness statement (we don’t have a reference number for this and it seems to be another document that the Inquiry hasn’t published yet).

Barr drew Thomson’s attention to the fact that in 2001 the authority to travel abroad [MPS-0006714] recorded only two people being part of this supposed conspiracy:

‘Q. Why has two in a document generated in 2001 become four in your evidence before the Inquiry today?

A. I think it’s a larger number. I do not think that’s accurate.’

Barr asked Thomson about the nature of the conversations he had with L1, L2, L3 and L6, but he was unable to give any specific examples of what was said.

Barr also dug deep into why Thomson thought this supposed murder plot was real:

‘Q. These are people you have described as being involved in essentially minor criminality to advance the cause of animal liberation… Murder is an entirely different ball game… What made you think that any of these four people was capable of that?

A. Because what you describe as minor, they had an ability, a desire, to visit real harm on people and to take satisfaction from it…

Q. Can you give the Inquiry an example of L1 inflicting physical harm on another human being and taking satisfaction from doing that?

A. On a specific day, date, time, place, no…

Q What’s the most specific recollection you have that would support the assertion that you have just made?

A. Home visits, I think…

Q. How many times did you witness L1 being violent in this way?

A. I don’t know.

Q. Why don’t we have any reporting of that?

A. I don’t know.’

Barr asked similar questions about all four of the activists Thomson had named, trying to establish why he believed them to be violent. Thomson was completely unable to cite any real incidents.

He answered all Barr’s questions about specifics with a nebulous refusal to be pinned to any certainty: ‘I can’t remember’; ‘if there was it would have been reported’ and even ‘sorry, I have forgotten the question’. He was visibly uncomfortable by this point.

Barr pointed out there are no (or at least, no surviving) intelligence reports at all about the conversations leading up to this incident. All we have are the management notes.

‘Q. Was there any discussion with your managers about whether or not this should be written up?

A. Not that I can remember.’

This is problematic for Thomson because, while we have internal SDS records that show him telling his managers that this plan existed and them building this incredibly tortuous operation around it, there is no contemporary record at all of any of these supposed conversations taking place between the activists, and no first-hand accounts at all of the meetings and conversations they are supposed to have had.

The only meetings about this plan on record are those held by the police. This fits with the activists’ version of events, as they say it simply didn’t happen, there were no such discussions, and the first they have heard of this plot was very recently, when it was described in the Opening Statements to this Inquiry.

ALWAYS FRANCE FROM THE START

Many aspects of this supposed plot clearly trouble Barr. He asks about when France was first mentioned as the destination for the arms deal. Thomson replied that it was later on, ‘after this report, when things began to firm up’.

However, that makes no sense. Although the 31 October note specifically states that nothing has been planned yet, the title of the document is ‘the French Connection’, and it mentions the possibility of jurisdictional problems in France.

Another internal note from just a week later, dated 6 November [MPS-0004441], seeks authorisation for Thomson to travel to Istanbul. We look at that trip in more detail in the section on foreign travel. Importantly, the note also states:

‘There is a plan to obtain black powder and a gun from France through a French animal rights activist.’

Thomson eventually concedes that France must indeed have come up earlier.

L3 in France on the trip with James Thomson, January 2001

Another document [MPS-0009484] records a meeting on 10 November 2000 between Thomson and two of his managers, Bernie Greaney and Noel Warr, which took place at Thomson’s home.

Thomson says that kind of informal meeting at home was not unusual. It was common SDS practice, and he doesn’t seem to think it posed any kind of security risk. This particular meeting was about events on 9 November – the so-called ‘dry run’ to Calais.

True to form, Thomson says he cannot really remember anything about the trip. He took a long time to answer many of the questions, but he did eventually admit that he travelled to Calais with L1 and L1’s girlfriend.

Thomson claims the purpose of the trip was to see what security was like at the port, and that they were in fact stopped and searched whilst going through customs. His answers were unconvincing, using hedging phrases like ‘I presume I was’ to imply that he has no reliable memory of this at all.

The meeting’s notes record that Thomson told his managers he would actively reassure L1 and his girlfriend that, despite the stop and search, the plan to secure a firearm from France was still sound.

He says that he did do that, which is completely ludicrous for someone whose supposed mission was to prevent the acquisition, as Barr pointed out:

‘You are a serving undercover police officer trying to encourage L1, L2 and L3 to continue with a plot to obtain an illegal firearm with the intent to kill or seriously harm another human being…

In terms of participation in crime, isn’t seeking to reassure your fellow conspirators to continue with the plot at a moment of uncertainty the wrong thing to do?’

Thomson answers that he doesn’t really know now why he did it, but he is nonetheless somehow sure that it was the right thing to do, and that he was always in control of the situation.