UCPI Daily Report, 10 May 2021

Tranche 1, Phase 2, Day 13

10 May 2021

Evidence from witness:

‘Madeleine’

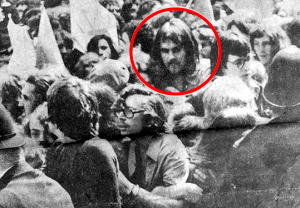

‘Battle of Lewisham’, 13 August1977

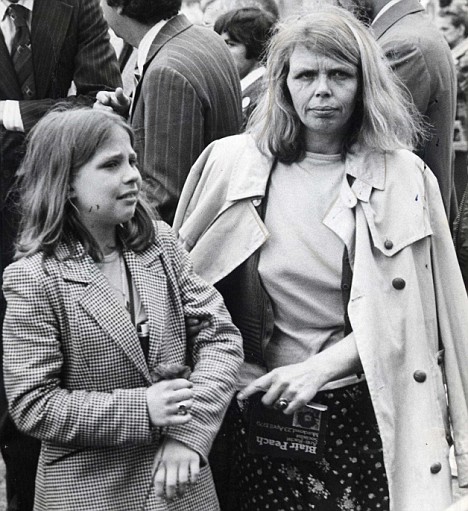

The 10 May hearing of the Undercover Policing Inquiry was focused on ‘Madeleine’, one of the women deceived into a sexual relationship by undercover ‘Vince Miller‘ (HN354, 1976-1979), one of four women that he has now admitted to having sexual contact with.

She is the first person to give live testimony on her experience of the relationship and undergo questioning on it (another woman, ‘Mary’, had her statement read out by a lawyer last week). She gave a powerful account of her own activism and and time as a political campaigner with the Socialist Workers Party (SWP). Despite questions from the Inquiry that crossed the line, she gave an open and quietly compelling description of how she was deceived by Miller.

Miller is claiming it was only a one night stand, but Madeleine steadily demolished that, with a detailed account of the night they got together and their subsequent relationship. She went into the conversations where he emotionally manipulating her feelings, then suddenly withdrew as his time in the field came to an end. This included pointing to records of conversations she had with others at the time.

Miller is giving evidence tomorrow, 11 May.

It was forty years before she learned the truth, in 2018, and was able to deal with the knowledge, but the empathy that guided her activism was clearly now extending to all the other women affected – noting how much damage her younger self would have experienced if she had learned of it at the time.

Madeleine provided a witness statement to the Inquiry in February 2021 but, as Inquiry delays meant she had to produce it in a hurry, it didn’t include everything she has to contribute.

BACKGROUND TO AN ACTIVIST

Barricade on Cable Street, 4 October 1936 [Pic: Bishopsgate Institute]

Her father was a committed anti-fascist, at the Battle of Cable Street in 1936 when an alliance of antifascists stopped the British Union of Fascists marching through the Jewish area of London’s East End. He then served in the International Brigades fighting fascists in the Spanish Civil War, and after he returned he joined the British Army simply to fight the Nazis.

Madeleine was about 15 when she joined the International Socialists (IS), which later became the Socialist Workers Party (SWP).

She had a break from activism when she was a student, but rejoined the IS Walthamstow branch in about 1973, and became an active trade unionist. This is the branch spied on by Miller throughout his deployment.

REVOLUTION, VIOLENCE & PLAIN OLD PAPER SELLING

Like with other non-state witnesses, the Inquiry are keen to find out just what was meant by the politics of the SWP, revolutionary politics and talk of violence. And again, like other such witnesses, she calmly dismantled the many (deliberate) misconceptions the police held of the group.

The SWP wanted an end to the constant class conflict of capitalism, seeking a fair and just socialist society, she explained. She rejected the Inquiry’s characterisation of the SWP as trying to overthrow parliamentary democracy:

‘We basically believed that extra-parliamentary activity was essential because we wanted to increase democracy, we felt that people should be active at all levels, not just voting once every five years. Our belief was in broadening participation in democracy…

‘We were not a terrorist group, we were not a violent group, we basically wanted to build a mass movement.’

Madeleine took issue with another mischaracterisation, disputing the implication that SWP members ‘infiltrated’ trade unions, rather they were trade unionists themselves and sought to support others.

They sold their Socialist Worker newspaper, held public meetings, and went on demonstrations:

‘Perfectly legal and legitimate methods.’

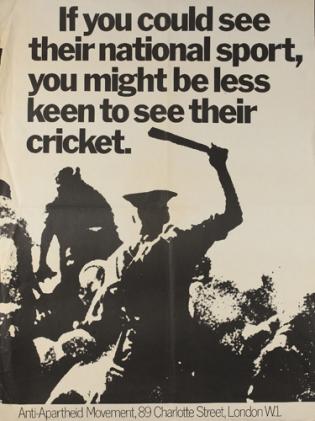

In the 1970s the far right were in the ascent with neo-fascists openly attacking minority communities and murdering Black and Asian men. Though the SWP, Madeleine was involved in the movement opposing fascism.

She said the SWP were opposed to active violence as counter-productive, and even expelled Red Action from the party.

WALTHAMSTOW SWP

With a membership of more than 40 people, the Walthamstow branch of the SWP was comparatively large, so split in two in 1977 – one covering Walthamstow & one covering Leyton/ Leystonstone.

This was the period when Miller was infiltrating. He became Walthamstow branch treasurer, and later district treasurer and social committee organiser for the Outer East London District Branch. This latter role would have entailedorganisingfundraising gigs and other socials.

The branches held regular meetings, as well as moresocial events. As people dedicated to the same ideals, their lives were very enmeshed:

‘We had a message to spread; we had a world to build’

All members were involved in selling papers, every week. They had regular pitches in the markets on Saturdays, and on weekdays would often sell papers outside factories, door to door on estates, and of course at any demos.

There were lots of demonstrations, about all sorts of issues, taking place most weekends.

The group were also active fly-posting and leafleting, to let people know about the speaker meetings they organised.

Madeleine lived in a large flat-share, with a huge living room and kitchen, four bedrooms. It was close to two popular pubs, so it was common for friends to come back after the pub closed.

Miller referred to it as ‘a drop in centre for SWP activity’ which Madeleine dismissed as sounding formal and functional, rather than domestic and sociable

BRANCH ACTIVITY – ‘A LITTLE BIT OF EMBROIDERY’

The Inquiry showed some reports on the branch’s activity. At one branch meeting in June 1977, 25 people listened to a talk on revolutionary feminism by a speaker from the SWP’s Newham Teachers Branch [UCPI0000017456].

Madeleine noted the women’s liberation movement was having a big impact on people’s thinking at the time. Women were not just oppressed as workers, but as women too. In essence they had two jobs – one at work to make ends meet and the other domestically:

‘We saw that the personal was very much political.‘

June 1977 saw the Queen’s Silver Jubilee, marked with a one-off Bank holiday. Not enamoured of the deference and imperial overtones of the occasion, Walthamstow SWP organised a family anti-Jubilee picnic in Epping Forest. The Inquiry asked if the picnic was likely to involve any public disorder:

‘Absolutely not, no. It was just a picnic. With children, I might add.’

The branch was also involved in protests at Sainsbury’s, with the Inquiry focusing on a report where mention was made of ‘occupying’ its supermarkets:

‘We felt supermarket prices were kept artificially high to extract profit for shareholders.’

Madeleine’s motivations andher politics shone through, as she spoke of the ongoing need to campaign about povertyin this country, illustrated by the existence of food banks, the estimated four million children living in poverty right now, and the recent campaigning of Marcus Rashford around school meals:

‘And now I’m thinking to myself, we were so right.’

Once again, she had to correct the Inquiry’s exaggerated ideas of their activity, explaining that they didn’t ‘occupy Sainsbury’s at all:what they probably did was stand outside with banners, handing out leaflets and talking to shoppers.

‘I believe that food, like clean water, fresh air, shelter, etc, are basic human rights.’

A July 1977 report [UCPI0000017571] of a meeting of 30 people describes their intention to produce bulletins for particular workplaces. Asked if this was done with the ultimate aim of recruiting, she once again rejected the suggestion of a hidden agenda, saying the aim was to get workers to:

‘build the movement, not necessarily get them to join SWP… we weren’t a secret sect – we were very much community based.’

Other reports showed cooperation with other groups – for instance, Women’s Voice involved a lot of SWP members, but also women who were not.

The July 1977 report claimed that the branch:

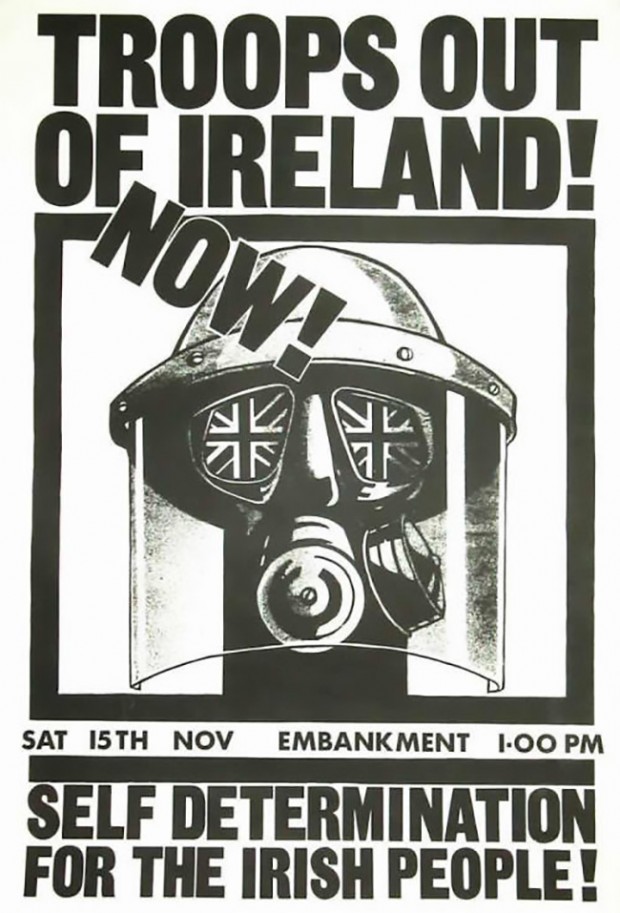

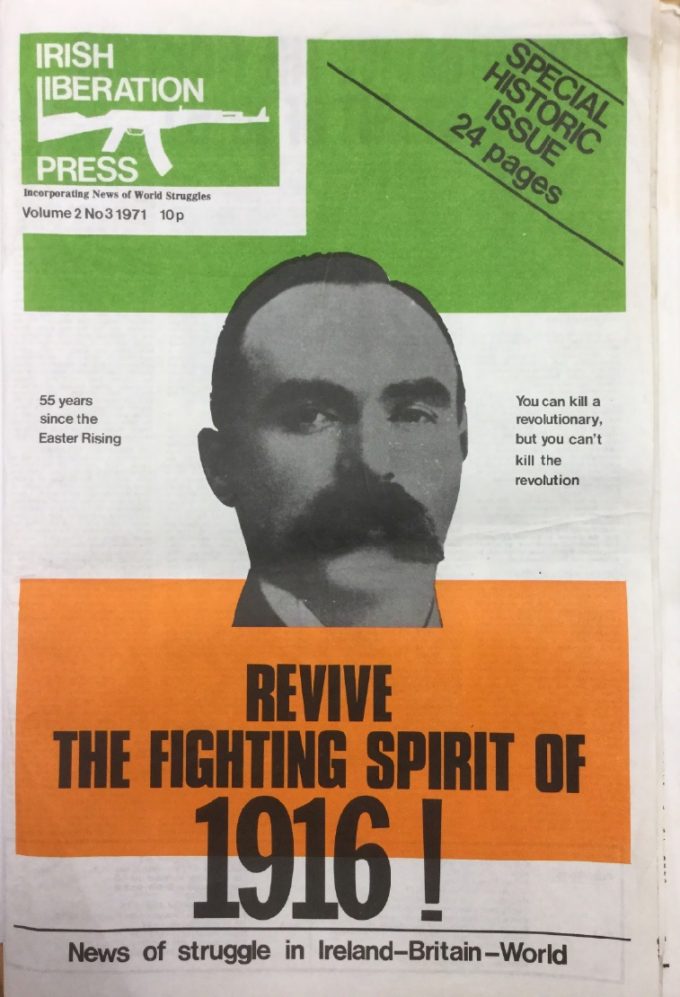

‘Restated its support for the Provisional IRA but remained critical of that organisation’s policy of random bombing of working class people.’

Again, Madeleine contradicted the characterisation:

‘We did not support bombing at all. Absolutely not. We supported a united Ireland, and we felt that Irish people had a right to self determination, and we saw British army as basically an occupying force’

Her witness statement refers to support for self-defence against the British Army and the Royal Ulster Constabulary. She explained that attacks by those institutions are well documented, and defence doesn’t mean physical violence, but non-cooperation in the form of things like rent strikes, workplace strikes.

She highlighted a practice familiar from spycop reports seen earlier in the hearings, of taking the most extreme or hyperbolic statement at a meeting and portraying it as the whole group’s real basis:

‘There’s a little bit of embroidery going on in many of the reports. There would have been people there who would have expressed opinions that we wouldn’t necessarily agree with, but we would discuss and debate and argue with them.’

REFUGEES FROM TORTURE

An August 1977 report [UCPI0000011129] describes a branch meeting addressed by a refugee from the Chilean dictatorship that had overthrown the democratically elected socialist government in 1973.

He told the meeting that he felt that if the Allende government had armed those prepared to defend it, they may have stood a chance. The report says there was a great deal of discussion about the need to arm the workers in the UK, which Madeleine dismissed out of hand:

‘That’s absolute nonsense. Absolute nonsense.’

But could the SWP envisage a situation where they’d like workers to be armed?

‘We foresaw, as I’ve said, a new society where the vast majority basically organised themselves, took action, and decided things would change…. We weren’t the Red Brigades, or anything like that; we didn’t support that type of activity. We basically believed… the working class would bring about this change, not us.’

Not content with this, the Inquiry highlighted the Chilean speaker’s observation that no people’s militia could directly oppose a trained army, so the only way to defeat it would be infiltration. So, the Inquiry asked, did this mean that the SWP considered infiltrating the Army?

Madeleine scoffed at the suggestion. Walthamstow SWP was selling newspapers and not even occupying Sainsbury’s.

The Inquiry failed to note that the whole issue was about the fascist overthrow of the democratically elected Allende government by the murderous General Pinochet. The refugee was actually speaking about counter-subversion, which was supposedly the SDS’s remit.

The report concluded with a mocking description of a branch member crying, and:

‘Someone threw an epileptic fit which ended my observations.’

Madeleine explained that they knew Chilean refugees who had been tortured in Chile, electrocuted and threatened with death. As compassionate people, they found that emotionally moving. That the spycop found it funny beggars belief.

FASCISTS ON THE RISE

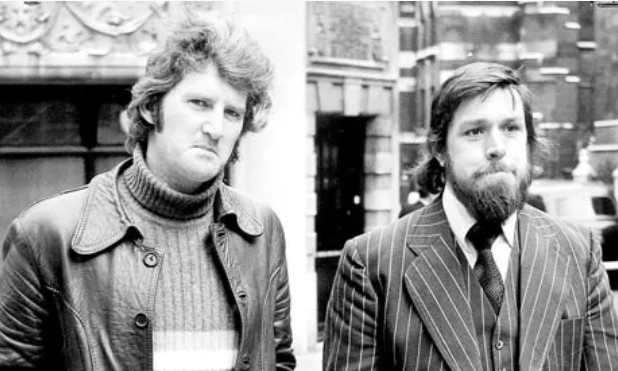

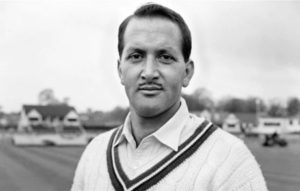

John Tyndall (holding record), National Socialist Movement HQ

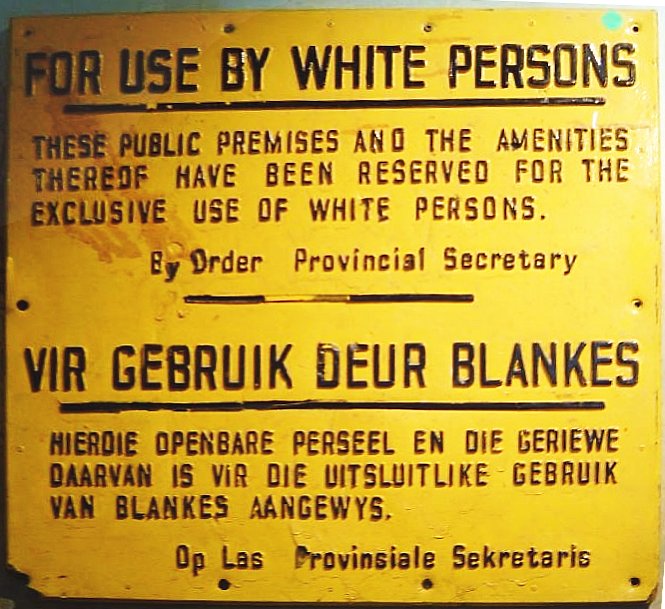

Calling the National Front fascist is no exaggeration. Madeleine supplied a photograph [UCPI0000034395] of future NF leader John Tyndall in Nazi uniform in front of a framed portrait of Hitler.

Madeleine described how her generation was dealing with parents traumatised from the Second World War, and yet these avowedly Nazi groups were allowed to organise and demonstrate, seemingly with the approval of the State and the protection of the police. The SDS was not monitoring them at all.

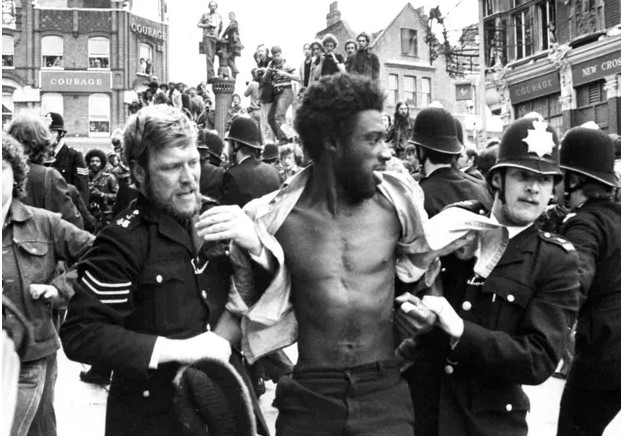

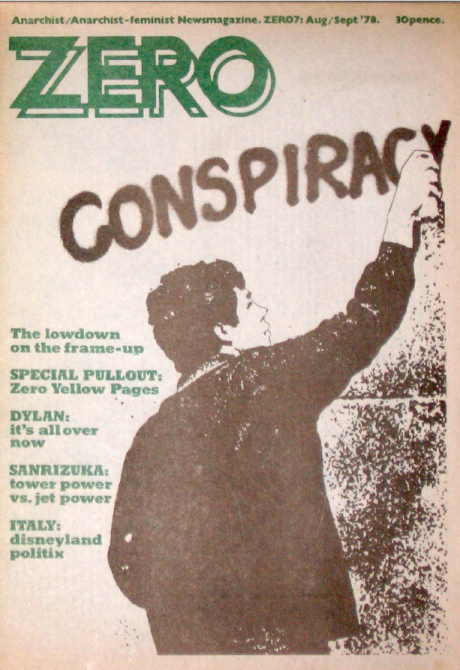

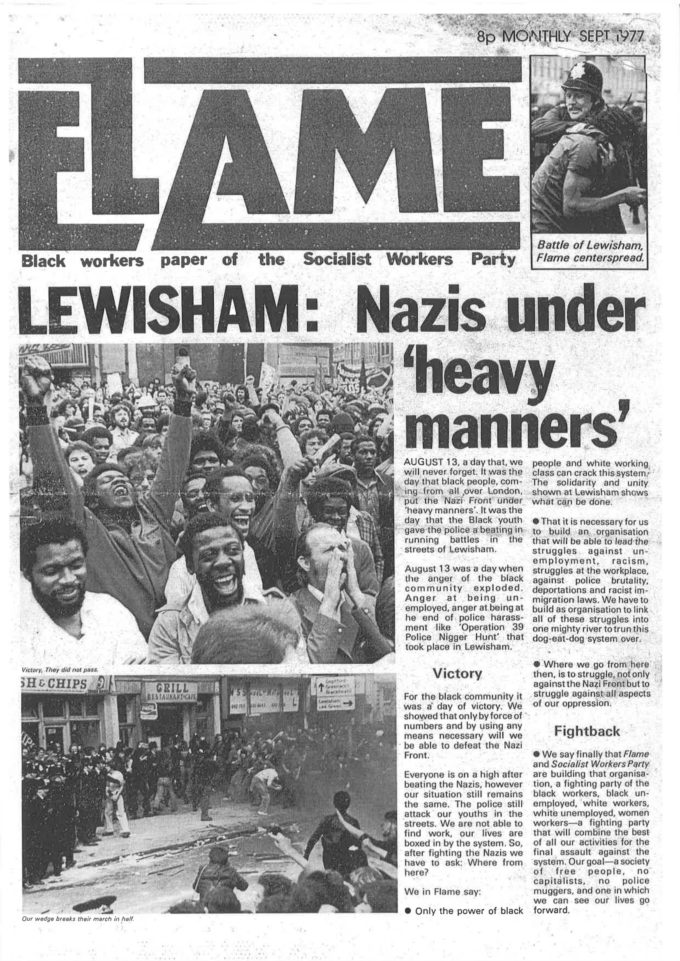

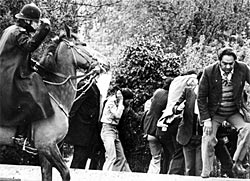

August 1977 saw a key moment in the fight against fascism in Britain. The National Front were organising a march in Lewisham, and there was a huge counter-demonstration. The collision of the two became known as the ‘Battle of Lewisham‘.

Spycop Vince Miller says Walthamstow SWP members went to check out the route of the march the night before, and deposited piles of bricks that could be used the next day. He also claimed they took weapons with them in bags on the day.

Madeleine utterly denies all of this. There is no evidence that anybody ever planted any bricks at all.

Madeleine attended the demonstration of 13 August with comrades from her branch.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

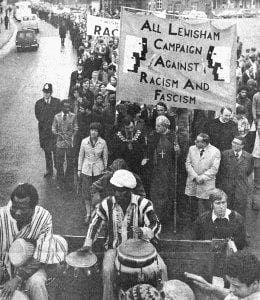

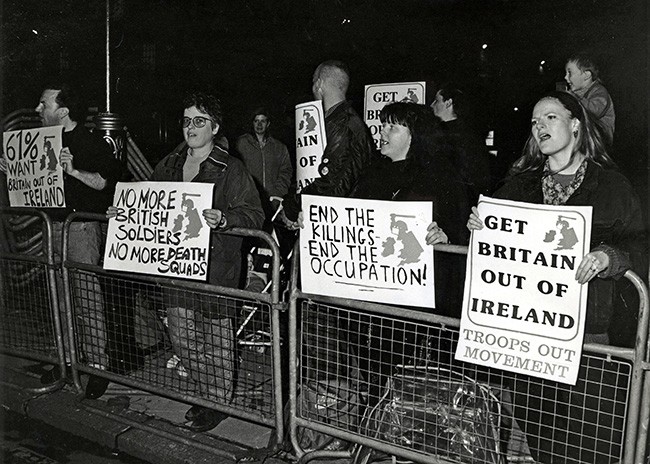

The Inquiry asked Madeleine about the All Lewisham Campaign Against Racism And Fascism (ALCARAF), which it described as a coalition of the SWP, International Marxist Group and Communist Party of England (Marxist-Leninist).

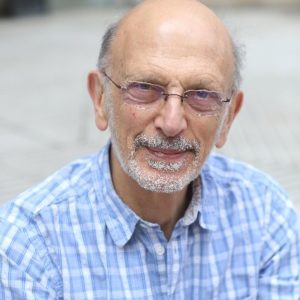

National Front ‘Stop the Muggers’ banner, 1977

She explained it was much wider than that, bringing in trade unions, faith groups and church leaders. It’s extraordinary that churches has noticed fascist violence on the streets and took action, yet the SDS officers say there was no problem they were aware of.

Madeleine explained ALCARAF been formed in January 1977 in response to National Front violence and open police racism. This is vital context to understand the Lewisham protests.

Instead of doing anything about the NF’s ongoing street violence in the area (the Sikh Gurdwara had been attacked, as had shops and individuals in the area), police launched an ‘anti-mugging’ crackdown – ‘muggers’ being a racist trope at the time, as evidenced by the NF’s ‘Stop The Muggers’ banner.

In one large operation local police had conducted house raids, smashing in doors, arresting mostly Black people. Madeleine recounted how a white woman arrested in a raid was strip searched by police and subjected to vile comments about how she was catching diseases from living with Black people.

60 people were arrested, 21 were charged. The Lewisham 21 Defence Committee was set up to support them. They held a march that was attacked by the NF. Acid was thrown on a young girl, one person’s jaw was broken, another knocked unconscious. This alone is more public disorder than the SDS has managed to pin on the SWP, and yet nothing was done.

Just before the Lewisham demonstration, the NF’s National Activities Organiser, Martin Webster, held a press conference and announced:

‘We intend to destroy race relations here in Lewisham.’

As an aside, Madeleine noted that Durham Police had invited Martin Webster to give a talk on law and order in December 1977.

She asked the Inquiry to show a photograph of the NF on the day [UCPI0000034396], in which one of them could be seen armed with a stick. Madeleine said:

‘We could see where their philosophy ends. My husband Is Jewish, his family have the yellow star of his great grandfather…. Part of the family tree ends in the 1940s at Auschwitz.’

THE BATTLE OF LEWISHAM

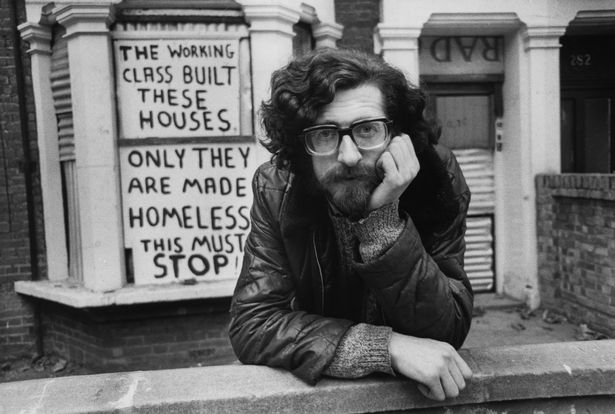

The Bishop of Southwark leads the ALCARAF banner, 13 August 1977

Against this backdrop of racism from both police and the NF, the August 1977 Lewisham counter-demonstration was always going to be full of outrage.

Police allowed the fascist march to go ahead, while changing the route of the anti-fascist one at short notice. Madeleine found herself trapped in a ‘kettle’ by Clifton Rise in New Cross. People climbed up the corrugated iron hoardings to escape the crush. There was a line of police blocking one end of the street.

People from the overlooking houses told them that the fascists were frightened by the sheer size of the crowd. The next thing she recounted was police horses charging down the street, right through the crowd of demonstrators.

The police led out the NF’s flag-waving contingent, but the rest of the fascists behind had almost no police protection even though many officers were available. ‘All hell broke loose,’ Madeleine remembered, describing missiles coming overhead from behind her.

She and her comrades wanted to get out of the situation. They were not involved in throwing things. She noted that the majority of people on marches were usually white, but this day saw a large proportion of Black people on the streets, and the police responded with aggression.

She felt that the police ‘just lost control and went wild’ in an outburst of rage vented against the local community. She recalled police vehicles driven into the crowd, indiscriminate arrests, and severe police violence, as they escaped and walked to a train station some distance away in an attempt to make it home safely.

MORE MEETINGS

The Inquiry showed some more reports on the SWP meetings. One from November 1977 [UCPI0000011513] held at a public library, was on the life and works of William Morris, a Victorian son of Walthamstow, known for both his wallpaper/ textile pattern designs and socialist beliefs.

The meeting was addressed by a speaker who ‘delivered a well prepared speech which he illustrated with photographs and slides’. The meeting was apparently that told Morris was a ‘pioneer of English socialism,’ even if his ideas were not entirely consistent with the SWP.’

Morris was pretty mainstream in thought and indeed in wallpaper design. Once again, the SDS was reporting on things that were in no way subversive or a threat to public order, and the documents were copied to MI5 where they are still held nearly 50 years later.

A report of a meeting in July 1978 [UCPI0000011337] shows Miller was involved in the branch’s Industrial Group, which organised sales of Socialist Worker at factories, picket lines and similar settings.

A January 1979 report [UCPI0000013063] says sales of Socialist Worker are going well on a local industrial estate, though they must avoid places with a predominantly Asian workforce as workers say they would be subjected to violence or the sack if they showed support.

Madeleine wonders if Miller had contact information for sympathetic workers at these factories, and if their details were passed on to industrial blacklists.

The report also mentioned School Kids Against the Nazis (SKAN) and says it ‘can, with short notice, get large numbers of school students on to the streets, should the need arise’. The Inquiry asked Madeleine if SKAN were able to suddenly create a mob ready for street violence.

Yet again, she had to deflate suggestions of insurrection. She explained that SKAN had been formed when the NF held a demo outside a school in multicultural East London. About 200 pupils had opposed it, with 15 arrests – all but one of them Black kids.

SKAN was a self-organising group of kids responding to the upsurge of racism around them:

‘The idea that we would have somehow had to have planted these ideas in their heads is a bit ludicrous really. It was their own experience.’

SELF DEFENCE IS NO OFFENCE

In her statement, Madeleine notes other reports are deliberately facetious, and often selectively quote a few individuals’ opinions rather than the general view, even just picking up on comments made by members of the public – such as arming themselves with catapults [UCPI0000011196].

Madeleine said this suggestion was more likely made by a member of the public, and would have been ineffective given that a young woman selling the Socialist Worker had her pelvis broken by NF thugs with a sledgehammer. Rather:

‘the collective focus was was on how to stay safe by remaining in groups and avoiding situations where we might come under attack.’

The Inquiry did not address the above in the live evidence, but it did turn to another instance of SWP members protecting themselves against vicious racist violence.

A November 1978 report [UCPI0000012924] of an SWP meeting (of 22 people) details the compiling of a rota of members who would stay at the house of a Black woman with a Jewish boyfriend who needed protection from attacks by the National Front.

The report said that Dagenham police confirmed that bricks had been thrown through the windows at the house, one with an extreme right wing leaflet around it, the other bearing the letters DAK. The report said DAK stood for ‘Dagenham Axe Clan’.

The transliteration of ‘K’ standing for ‘Clan’ is unsettling. It seems like the police were attempting to deflect from the use of the word Klan, and the direct violent racism implied by it.

Again, these attacks are each worse than anything Miller has managed to conclusively attribute to the SWP. It disproves the claims that the SDS didn’t know about any threats from right-wing groups. And yet, there appears to be no record of the DAK being of interest to the SDS.

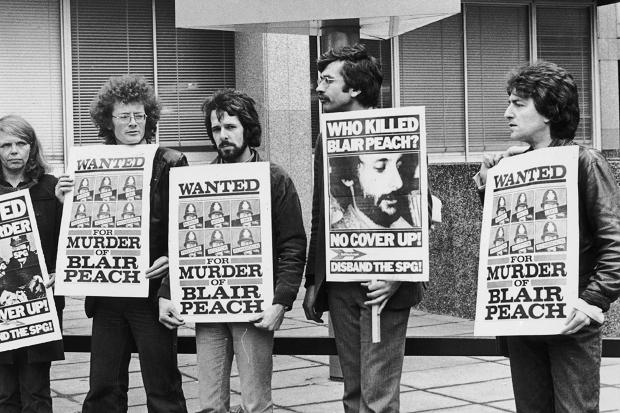

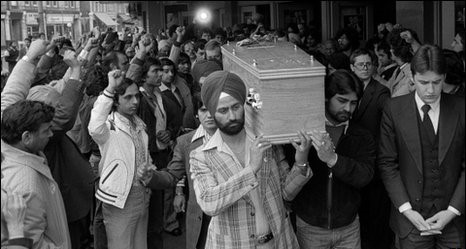

DISBAND THE POLITICAL POLICE

After SWP member and anti-fascist Blair Peach was killed by police at a demonstration against the NF in April 1979, there was a wave of outrage across the country. There were calls for a public inquiry into his killing, and for the notorious unit responsible, the Special Patrol Group (SPG), to be disbanded.

A July 1979 SDS report [UCPI0000021044] describes a Waltham forest District SWP meeting entitled ‘Police are the Murderers: Disband the Special Patrol Group’.

Madeleine reminded us of the unauthorised weapons and Nazi regalia found in the lockers and homes of SPG officers after they had killed Peach.

The report quotes a speaker as saying dissolution of the SPG is a necessary step on the path to socialist revolution. Madeleine broadly agreed – the SPG were effectively a repressive, paramilitary political unit, the opposite of policing in response to actual community need.

Although the meeting had not been advertised, two strangers arrived, separately, and were presumed to be police. The manner of their dress, their reluctance to divulge any details about themselves, and their leaving early gave them away.

The Inquiry asked if the meeting was private because it was doing something sinister. However, Madeleine explained that, as SWP meetings were being subject to fascist attacks, the party had simply become more security conscious.

PERSONAL DETAILS

The Inquiry then showed a report from November 1977 [UCPI0000011550] detailing Madeleine’s employment at a school, including her salary, start date, and a physical description of her. Another report from 1979 [UCPI0000021299] records her new job working on buses. Why did the spycops record this kind of personal info about her (and others)?

‘I’m outraged really. I find that a gross invasion of my privacy… Why did they need a detailed physical description of me? To what end? What was that used for?… I got a job in a school because I loved kids… and liked working with children very much.’

Even more disturbing was a report on Madeleine’s wedding [UCPI000011289]. She noted that, from her Special Branch Registry File number in the report, her file was opened in 1970, when she was only 16. Part of the details with that report are redacted:

‘I find that really, really sinister’

She demanded that the Inquiry reveal what’s been blacked out, and explain why they don’t want her to see information about herself from 50 years ago.

WELCOMING THE SPYCOP

It appears that Miller joined the Walthamstow branch of the SWP in early 1977. He made contact via a Socialist Worker seller at Walthamstow Market.

The branch was always keen to welcome new members. Madeleine recalls him seeming an ordinary working class guy, in contrast with the largely white-collar membership.

He became very active in the group, selling newspapers papers, fly-posting, joining pickets at the Grunwick strike. In all these things, his ownership of a van made him invaluable. Being the one with the reliable vehicle had rapidly became standard tradecraft for spycops since the early 1970s. It meant they were told of any action that needed transport, they got to chat to people while driving, and drop them home which provided opportunity to get their addresses.

Madeleine remembers Miller as a sociable person, always first to the bar after a meeting, well liked by all:

‘He was very enmeshed in the group, socially and politically.’

An old flatmate of Madeleine’s has located diaries from that time. They show that Miller visited their home as early as May or June 1977.

When Madeleine first knew Miller, she was married, and thinks she was probably less socially active and less friendly with him then, but increasingly regarded him as a friend after her marriage broke up in the autumn of 1978.

ROMANTIC DECEIT

In the summer of 1979 Madeleine was 25 and newly single. She was not actively seeking a relationship after the end of her marriage. She described how shy and quiet she used to be; her husband had been extremely possessive and abusive so it was only after she left him that she felt more confident socialising and talking to other men. She was still feeling vulnerable when she got together with Vince but believed she could trust him:

‘I thought he was lovely. A really nice guy. I thought he was a genuine, lovely, easy going person, I thought he was sensitive, he had this story of heartbreak and all the rest of it. I felt he was looking for genuine relationships with people.’

Madeleine was asked for her account of the house party in Ilford where they became romantically involved. She recalled 40 or 50 people, mostly young people connected with the SWP, there, drinking and dancing.

Miller turned up late and sat down. Madeleine went to try to get him to come and dance, but:

‘He pulled me onto his lap and that’s where I stayed for the rest of the night.’

He said how hard it had been to get to know her, which surprised her as he hadn’t indicated any romantic interest before. She trusted him and was happy to stay there, chatting and flirting.

Some friends came to get her to dance, but Miller put his arms around her and said ‘ ‘no, she’s quite happy here’. She found this funny and laughed.

Later, when the friends were leaving, Miller assured them he would get Madeleine home. He took her back to her flat and they began a sexual relationship. He stayed the night.

‘I was very keen on him. I thought he was lovely, a really attractive guy. I was very keen for it to continue, I was never looking for a one night stand or casual sex with anyone.’

Madeleine says that they saw each other about once a week for a couple of months. They always met at her house, she never visited his.

CYNICAL SYMPATHY

He told her a backstory, of having been in a long-term committed relationship that went toxic in some way, and how he’d had to leave all his possessions behind. The loss of this alleged relationship with someone he’d thought would be a life partner left him devastated and heartbroken, and he said he was too wary of get close to anyone as a result.

He also spoke of a troubled childhood that had damaged his ability to trust, and how he’d always had to rely on himself.

His cynical tale of woe is another piece of spycop tradecraft, one that other women deceived by spycops will recognise all too readily. By telling a story of a damaged upbringing, the officers gave themselves cover for not wanting to tell a full life story. More than that, it made the listener feel that they had been trusted, and so would be likely to reciprocate that trust.

Miller never stayed over after that first night. At some point in the early hours he would suddenly say he had to go home, saying ‘I have to wake up in my own bed because that’s where I feel safe’.

Madeleine accepted that explanation, and hoped it would change. She didn’t consider herself as part of a couple, but she hoped it would become that, and she didn’t see anyone else:

‘He was the focus of my affections, as it were.’

Her feelings for him grew, as he surely knew:

‘I think in the beginning he seemed very keen on me. He became increasingly distant, and I began to become disappointed that it didn’t seem to be going the way I wanted it to go. And, yeah, I kind of became a bit upset about it.’

Her flatmates knew about her relationship. She has a very strong recollection of one asking in the morning ‘is Vince still in bed?’ and commenting on his bad manners in not staying all night.

THE LAST TIME

The last time she saw ‘Vince Miller’ was at a friend’s house. She hadn’t seen him for about a week and saw him sitting on the other side of the room. He was with another woman, and she sensed from their body language that there was something between the two of them. She now thinks this is the other SWP woman he has admitted deceiving into a relationship.

He ignored Madeleine and, when he left, she followed him into the street to ask him why he was being so distant. He said that he’d already told her that he couldn’t get too involved and that he didn’t want to get hurt again.

He said he was going to go to California to ‘find himself’. This is yet another early example of what became standard practice – spycops would cover the end of their deployment by feigning emotional distress and say they were going abroad to sort themselves out.

The depth of emotional turmoil conveyed by some of the later officers had huge impacts on those who loved them. More than one desperately woman deceived into a relationship went searching in the country where her partner was supposedly living, not knowing he was actually back at a desk job in Scotland Yard.

Madeleine and Miller hugged for a long time and parted ways.

THAT’S NOT WHAT HE SAYS

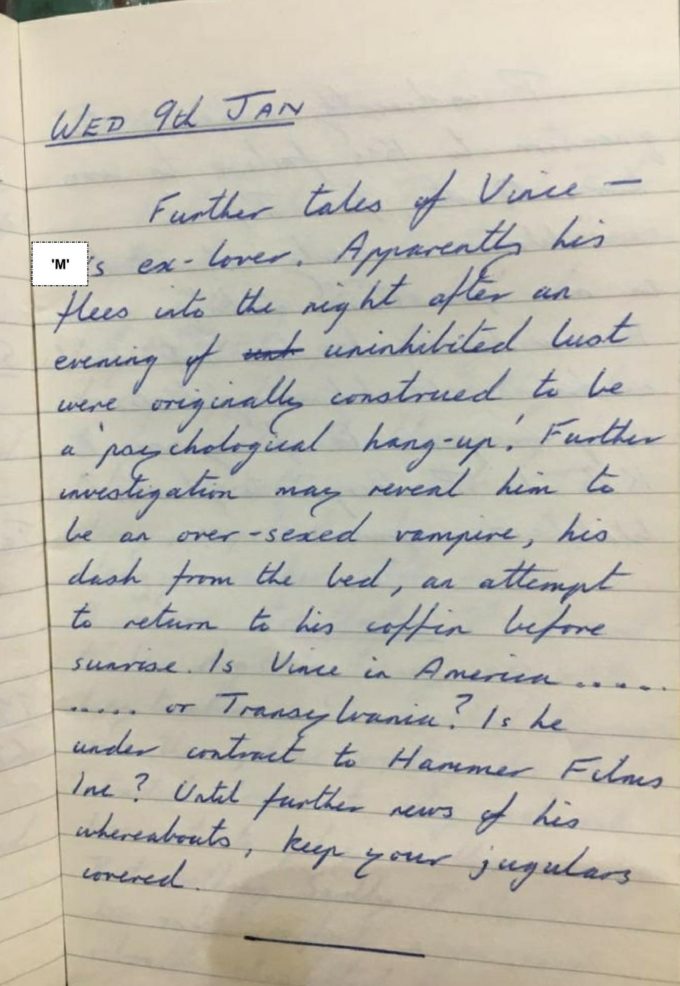

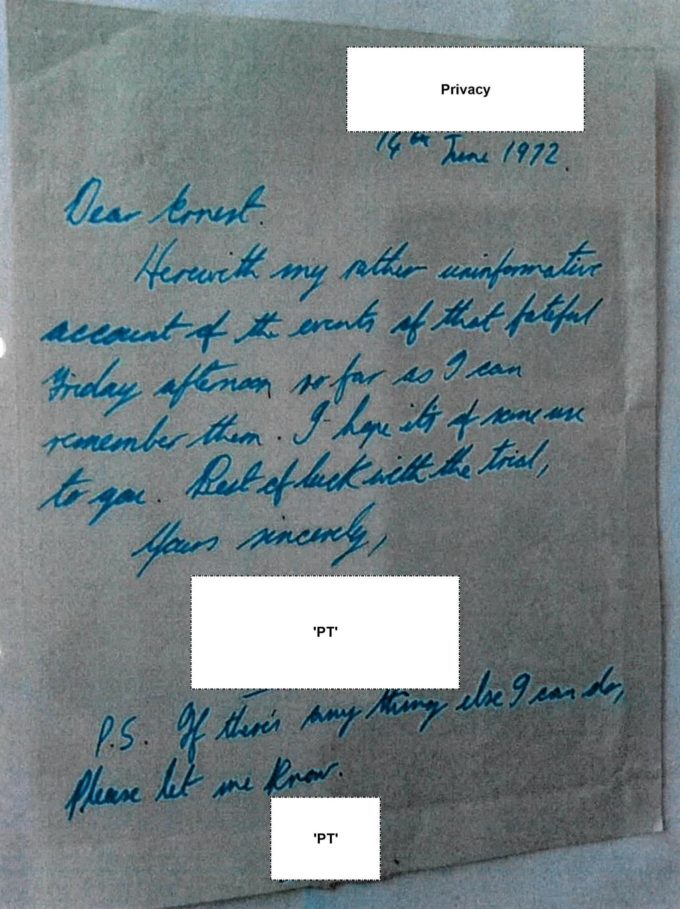

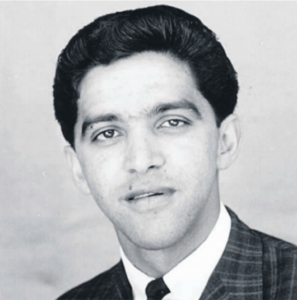

Madeleine’s relationship with Miller described in a friend’s diary, January 1980

In his statement to the Inquiry, Miller describes his relationship with Madeleine as a ‘one night stand’ with no hard feelings and said that the pair remained on good terms thereafter.

In his version, he uses being drunk as an excuse for starting the relationship with her, and for his other ‘one night stands’.

She says that, on the night they got together, he didn’t seem drunk and she certainly wasn’t.

Madeleine then cited a close friend’s diary entry dated 9 January 1980 [UCPI00000034310]

The friend describes Miller as Madeleine’s ‘ex-lover’ and, noting his persistent leaving before dawn, suggests that he may be some kind of vampire who needs to be back in his coffin before sunrise.

Madeleine remembers Miller’s departure damaging her self-esteem, leaving her feeling upset, disappointed and rejected. She saw it as part of a pattern with her marriage and thought:

‘God, have I made another mistake?’

IF SHE KNEW THEN

The Inquiry said that despite everything, the whole affair would have had little impact on her life if she hadn’t latterly found out the truth about spycops.

Asked how she would have felt to discover Miller’s true identity at the time, she said it would have been devastating. She was young and naïve, and would have been profoundly shocked and distraught:

‘I’d made myself very vulnerable to him and I trusted him, and to me it would have been an absolute betrayal… I would have regarded it, as I do regard it now, as rape.’

As it is, she had some fond memories of him, and used to sometimes think about him, hoping he’d come to terms with his troubles and had a happy life. But now:

‘To discover that I didn’t know him at all and that he was a fiction, that’s been quite difficult to get my head around. He doesn’t actually exist, it was all an act, wearing a mask… it’s really chilling and sinister… I just don’t know how people can behave like that.’

Despite promises by the Inquiry to reveal the real names of undercovers to the women deceived into relationships, it has not provided Madeleine his name though she has requested it. The Inquiry are effectively providing cover for a serial sexual abuser – who has admitted to deceiving four women.

‘Like the other officers who deceived women into relationships during their deployments, Vince Miller has lost the right to have his identity protected on privacy grounds. And, like the other women who were deceived into relationships, I should be entitled to know his real name.’

Full written statement of ‘Madeleine’

The speaker said Grunwick showed that at least a thousand comrades would be needed to attack or block the factory gates, and the plan would need to be enacted swiftly and forcefully to avoid it being stopped by police. The SWP have the ability to take such action, he said, but not the capacity to organise it.

The speaker said Grunwick showed that at least a thousand comrades would be needed to attack or block the factory gates, and the plan would need to be enacted swiftly and forcefully to avoid it being stopped by police. The SWP have the ability to take such action, he said, but not the capacity to organise it. The

The

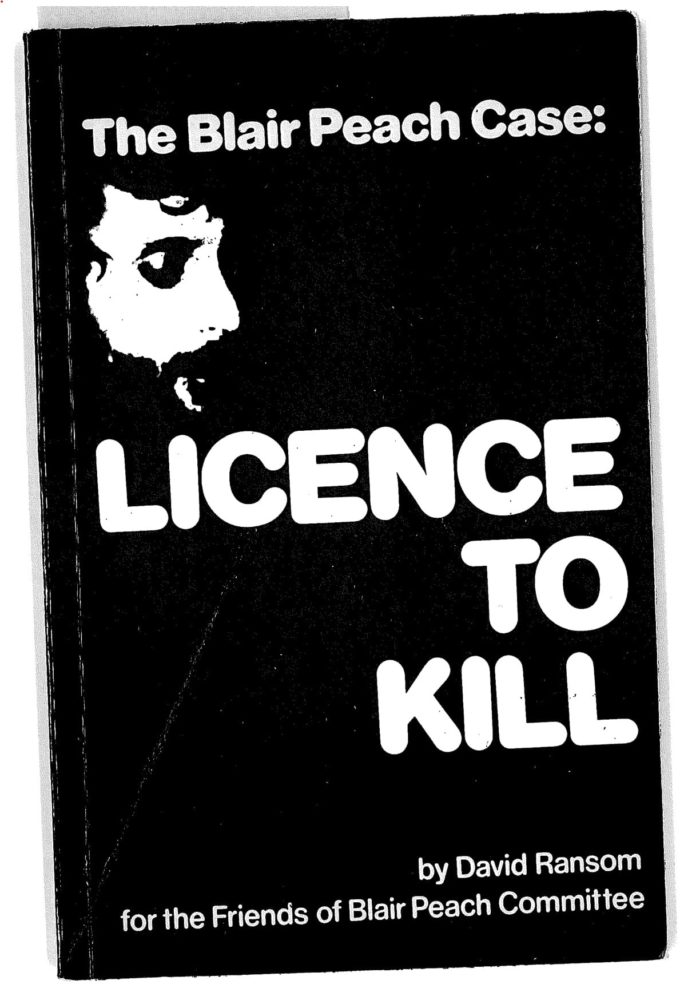

One of Peach’s friends and teaching colleagues, David Ransom, wrote a booklet called License to Kill about the killing of Peach and the Special Patrol Group. The chapter on the Special Patrol Group (SPG) is being published by the Inquiry along with the Cass report [

One of Peach’s friends and teaching colleagues, David Ransom, wrote a booklet called License to Kill about the killing of Peach and the Special Patrol Group. The chapter on the Special Patrol Group (SPG) is being published by the Inquiry along with the Cass report [

The Inquiry then took Chessum through a series of reports that, for the most part, demonstrate just how small the group’s meetings were, and how quickly the undercover officer made his way up through the ranks of the TOM.

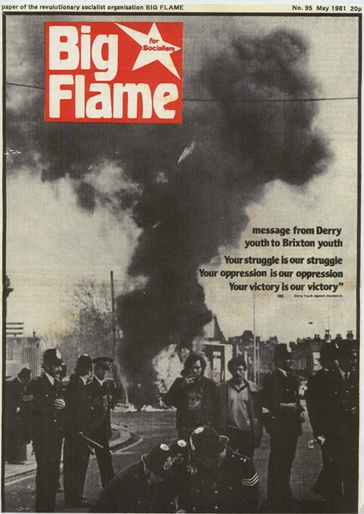

The Inquiry then took Chessum through a series of reports that, for the most part, demonstrate just how small the group’s meetings were, and how quickly the undercover officer made his way up through the ranks of the TOM. Chessum recalled that to counter the influence of these groups, an informal alliance had formed between Géry Lawless, other ‘independents’ within TOM, and members of Big Flame.

Chessum recalled that to counter the influence of these groups, an informal alliance had formed between Géry Lawless, other ‘independents’ within TOM, and members of Big Flame. Big Flame had been described as ‘libertarian Marxists’ and the Inquiry asked Chessum to explain what that meant. He said they differed from the more authoritarian, dogmatic groups found on the left – they didn’t have a strict ‘party line’ and were more open to discussing different viewpoints.

Big Flame had been described as ‘libertarian Marxists’ and the Inquiry asked Chessum to explain what that meant. He said they differed from the more authoritarian, dogmatic groups found on the left – they didn’t have a strict ‘party line’ and were more open to discussing different viewpoints.

‘

‘

He also joined the Spartacus League, which he confirmed was part of the IMG, though it could be joined without being in the IMG – people would be invited to join the IMG if they ‘proved their worth’.

He also joined the Spartacus League, which he confirmed was part of the IMG, though it could be joined without being in the IMG – people would be invited to join the IMG if they ‘proved their worth’.

He says he recalls Jill Mosdell (

He says he recalls Jill Mosdell (

He described his weekly routine. The groups he was infiltrating would often meet/ be active until late at night, so Sloan would sometime sleep at their homes, rather than at his bedsit.

He described his weekly routine. The groups he was infiltrating would often meet/ be active until late at night, so Sloan would sometime sleep at their homes, rather than at his bedsit.