UCPI Daily Report, 28 April 2021

Tranche 1, Phase 2, Day 6

28 April 2021

Evidence from witnesses:

Stop the Seventy Tour supporters block the coach taking the Springbok rugby team to Twickenham for their international against England, 20 December 1969. [Pic: AAM Archives]

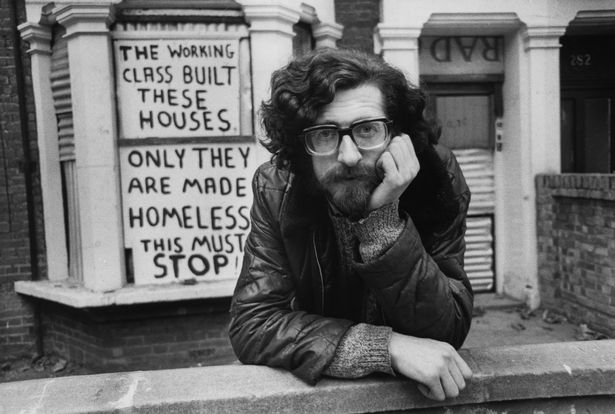

Piers Corbyn

Piers Corbyn was an engaged witness, who had the measure of ‘Sir John’, as he referred to the Chair multiple times. There was a sense that he got something out of been taken back to memories of his activities in the 1970s. At times he complimented the Inquiry on bringing so much of the material on him together, calling it a useful diary of his activities.

Corbyn moved to London in 1965 to study and the first demonstration he can remember attending was for the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. He participated in many other campaigns and movements, and confirmed that he attended both of the anti-Vietnam War demonstrations in 1968.

VIETNAM WAR CAMPAIGNING

Corbyn was not a member of the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign (VSC) as such. However, he did mobilise people and banners for demos, and maybe even did some stewarding. He said that the war in Vietnam was:

‘a formative crisis for tens of thousands of young people at the time and I was one of them.’

He was asked if he remembered seeing any violence at these demos – to which he responded:

‘I wouldn’t say any violence was initiated by demonstrators.’

The Inquiry was interested in the make up of the VSC. Corbyn described the IMG as ‘one of the most influential’ groups involved in the VSC. He said the IMG’s role, historically, was to mobilise people and make them aware of the issues.

SPARTACUS LEAGUE & THE IMG

Corbyn became president of the Imperial College Students Union, and then the editor of a London student newspaper, The Senate, around 1970.

He also joined the Spartacus League, which he confirmed was part of the IMG, though it could be joined without being in the IMG – people would be invited to join the IMG if they ‘proved their worth’.

He also joined the Spartacus League, which he confirmed was part of the IMG, though it could be joined without being in the IMG – people would be invited to join the IMG if they ‘proved their worth’.

The Inquiry took him to a report on the Spartacus League, dated January 1972 [MPS-0732360]. As with similar meetings, this took place at Corbyn’s home in Rendle Street. The meeting had been attended by officer HN338 (cover name unknown) who Corbyn was unaware of.

On page two of the report, the author detailed a discussion about the ‘Red Defence Group’, and how the IMG could ‘take over, run and use the organisation’ in order to recruit into the IMG. Corbyn pointed out that this report was authored by a spycop, and most likely reflected his assumptions, and the police’s prejudices, rather than reflecting the IMG’s actual intentions.

Corbyn said that he was ‘always interested in getting people to join in and stay active and make propaganda’.

He said if these reports were less redacted, or he was supplied with photos, he might find it easier to recall the people and events of 50 years ago.

MERGER

A report from June 1972 [UCPI0000015694] covered a conference that took place in May that year to merge the Spartacus League into the IMG. Corbyn was asked which category of attendee he would have fallen into – a delegate, a consultative delegate, an observer, or a visitor? Corbyn thinks he may have been a delegate. The Inquiry noted that ‘visitors’ could not take part in any votes and asked if this meant the conference was open to the public. Corbyn said effectively no, you had to be invited – either via a branch or someone else.

He was then directed to look at section that covered a speech made by ‘Surgitt’ – the party name (see more below) of a female member critical of male chauvinism in the group and which got various reactions. Corbyn was asked if this was an accurate description of the speech and the atmosphere at the time. He said ‘maybe that description is a bit over the top’ but ‘those types of things were said’ – not remarking on the sexist nature of the police’s report which described it as being unconstructive and amounting to an attack on men.

DEFINING REVOLUTION

Elsewhere in the report there was a mention of ‘fraternal greetings’ from a Peruvian member of the Fourth International, a revolutionary socialist international organisation of Trotskyists seeking an international revolution to overthrow global capitalism and establish world socialism. The speaker gave a rousing speech on revolution which included the phrase ‘the Revolution will not be won until Marxist blood is spilled in the street’.

Asked about how much this reflected the IMGs own position, Corbyn replied:

‘the IMG would say – as a not very funny internal joke – “if you care to struggle, we will ‘solidimise’ with you”. This meant that they would support, which is not always the same as endorse, all kinds of people engaged in the anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist struggle.’

Corbyn said that at the time, capitalism was in crisis, so a transition to a more socialist and more democratic society was needed. He pointed out that ‘revolution’ need not mean violence but could also be taken to mean a ‘fundamental change in the way that society was organised’. The IMG was a small group of a few hundred people and knew that they could not make this kind of fundamental change in society without wider support.

Corbyn wondered aloud if he was an ‘armchair socialist’ like many others of the time, but added that he was also very keen on talking to people about all sorts of issues (citing Ireland, workers’ struggles, tenants’ and housing campaigns, etc).

SUPPORT AND SOLIDARITY

He was asked, in reference to report [UCPI000008948] to explain what ‘Red Circles’ were. These were public meetings, held in places like pubs, with a variety of speakers on all sorts of issues, and some ‘lively discussions’.

The IMG did support many groups and campaigns and did not always try to control them, he explained. Sometimes they would set up a ‘Support Committee’. From the same document, Corbyn noted they were supportive of the Claimants Union, which worked to make sure people got the benefits they were entitled to.

The report mentions a ‘perspectives’ document produced by Corbyn, ahead of a discussion about merging branches. The IMG used coded initials in case these internal documents fell into the hands of Special Branch, but the spycop submitting this report included a key to this code as an appendix.

A discussion followed about the IMG’s use of ‘party names’ – ie false names when undertaking political activity. In this context, Corbyn noted that he was under surveillance for a decade, an endeavour which was probably a waste of police time:

‘I didn’t do anything dangerous, nor did anybody to my knowledge in the IMG.’

Corbyn was next asked about the relationship between the IMG and trade unions. He explained that the IMG wanted to develop into a wider field and move away from being student-focused. When asked if the IMG tried to gain control of any trade unions, Corbyn repeated his point about the IMG offering support, rather than seeking to take control of campaigns or other organisations.

One of the common themes running through many Special Branch reports – and other related documents – is the interpretation of any involvement from the ‘extreme left’ in a movement is rarely entirely genuine but in fact was fuelled by ulterior, sinister motives.

The next report [UCPI00007940] returned to the IMG/Spartacus League in 1972 in relation to the miners’ strike. It noted Corbyn was among one of those who advocating a strong militant approach, involving the occupation of the National Coal Board headquarters. He laughed at this, and told us about his part in organising a march from Trafalgar Square to the Coal Board, and had no recollection of trying to occupy the Coal Board.

There was mention in the report of a call-out for ‘three volunteers to take part in a special task during the demonstration which would involve breaking the law’, so he was asked about the IMG’s attitude towards illegality.

Corbyn responded that he still believes that there are just laws and unjust laws, mentioning the CHIS Bill currently going through Parliament which would give yet more powers to the police. In those days, the Government was trying to limit the powers of trade unions and the right to strike, and unjust laws such as these should be challenged and broken, he explained.

NON-COOPERATION

The next document referred to is a June 1972 report and a leaflet attached [UCPI0000008798] on the subject of the Metro Youth demonstration. This was produced by Corbyn, so the Inquiry asked why he had advocated a policy of not engaging with the police in the future.

He said the police did not have demonstrators’ interests at heart, but wanted them to take a route that took them down empty streets. The group had been right, in his opinion, to disregard the police on this occasion and instead go down Portobello Road.

Developing his position, he said there were times when it was necessary to talk to the police such as times when squatting. However, as far as he was concerned, ‘we were running our own show’, they would listen to what the police had to say but we ‘had to maintain that we had the right to protest and demonstrate where we wanted’, subject to not endangering anyone.

ELECTION CAMPAIGN

He was next directed to a report from March 1977 [UCPI000017814] which noted that Corbyn was being put forward as the IMG candidate for Lambeth Central in the forthcoming Greater London Council elections. He replied he was proud to be a candidate, querying why Special Branch were interested in a local election campaign.

A further report from around the same time [UCPI0000017335] included reference to flyposting. Corbyn was asked if this meant illegal fly-posting. He said it depends, and pointed out that there was lots of corrugated iron around, and people would fly-post on it.

Given their focus on flyposting, the Inquiry seem to be considering it amounts to a serious crime, possibly justifying the undercover policing. If that is their view, then it is a transparently desperate and partisan position, especially given that spycops themselves did it while undercover.

THE BATTLE OF WOOD GREEN

There was then a discussion about the IMG’s participation in an anti-fascist demo on 23 April 1977 on Ducketts Common, which became known as ‘The Battle of Wood Green‘. This was a significant counter-Nazi mobilisation which Corbyn did not recall at first, though he subsequently remembered Tariq Ali and others ‘speaking from the back of a truck’ somewhere in Haringey.

FARE FIGHT

The next topic up was the Fare Fight campaign, referring to document [UCPI0000021485] from October 1976.

This was a campaign to not only stop the Greater London Council implementing unjust fare rises on London Transport but to reduce fare prices. It gave Corbyn an opportunity to educate the Inquiry on the campaign, which had wide support among the public.

The campaign was passive in nature and part of its tactic was to jam the legal system around fares. He was incredulous that it had been spied on, given its peaceful nature.

THE IMG ON IRISH REPUBLICANISM

The Inquiry then went back to April 1972 and a report [UCPI0000008129] about a meeting of London IMG members. In relation to this, Corbyn was asked about the IMG stance on the situation in Northern Ireland, in particular their apparent support for the Provisional IRA.

He averred that it depended on what you meant by ‘support’. He said the IMG supported the idea of a united Ireland but there were things the IRA did that they did not support. Then again, there were other things which they did agree with, such as building community groups to help the unemployed:

‘It covered a broad front of activities’.

In this context, support meant solidarity with the IRA, through solidarity with the struggle of Sinn Fein, which was the political angle of the struggle.

He was subsequently asked about his involvement in Irish support groups such as the Irish Solidarity Campaign and Anti-Internment League. Corbyn said he had supported them but not been particularly involved. He noted that republican in those days did not necessarily mean being active in the IRA but referred to people who supported there being a republic of all Ireland in general. The word had to be read in that context.

SQUATTING

Piers Corbyn outside houses in Shirland Road, Maida Vale, London, which were barricaded by the squatter occupants against impending eviction, November 1975

We finally moved on to the topic of squatting for which Corbyn was best known for many years. He explained that he rented a place in Rendle Street but ended up taking the landlord to a rent tribunal. After this, he and his older brother Andrew took up squatting in the same area as a solution to their housing needs. Originally he thought of squatting as a hippy thing to do, but had eventually realised that it could be immensely useful. They set up an IMG ‘squatting faction’.

He was then asked about a January 1976 report which contained the Easy 111 news sheet of Maida Hill Squatters and Tenants Association [UCPI0000009509]. This led to a long discussion on the nature of the squatting struggle that Corbyn was involved with, in particular that of the Elgin Avenue squats. The campaigners there were in a struggle with the Greater London Council for housing.

However, Corbyn noted that squatting campaigns at the time often had a successful outcome in that people were rehoused rather than left homeless, particularly when it became clear that there would be resistance to eviction. It is in this sense that the following extract the Inquiry had focused on should be read:

‘Our collective organised strength and support meant that we could physically resist and in a confrontation, human justice would be on our side. So, whatever happened the Greater London Council had to lose and we had to win.’

Corbyn was asked for his views on eviction resistance. He explained that the barricades were both physical and symbolic/ political. The squatters were fighting for housing for everyone, and against properties being left empty.

The Inquiry read more of Corbyn’ comments from the newsletter and asked him about violence. Corbyn went to some lengths to explain the kind of eviction resistance that took place. Many squatters in the area would turn up and join in.

When directed to someone who was threatening to use sand and rubbish to resist and meet ‘violence with violence’, he replied that he was simply recording what people involved were saying, nothing more. It does not necessarily mean the squatters were adopting such tactics as a body.

Corbyn said he was surprised by the strength of feeling in Elgin Avenue, and how many people stayed put through that last weekend, despite the fear of eviction, and as a result they were rehoused.

He noted that he had begun squatting as a self-help housing solution and that the squatters of London were successful in that so many of them were eventually given more secure housing by councils.

ANARCHISTS – GUILT BY ASSOCIATION?

Following on from squatters, Corbyn was next questioned on his association with anarchists.

A report from April 1979 [UCPI0000021215] describes a meeting at Conway Hall on a ‘People’s Commission’.

There was a speaker from the ‘Persons Unknown’ trial (the support group which was spied upon by ‘Graham Coates’ (HN304, 1976-79) who is due to give evidence to the Inquiry all day on Friday 7 May).

Corbyn was asked if he shared aims and objectives with anarchists, to which he replied:

‘I don’t come and go to meetings based on who’s there. I come and go to meetings based on what needs to be said.’

Corbyn regarded the anarchists as part of the myriad other groups which existed at the time, including religious ones:

‘I just regarded them as people who were operating and hoped they would cooperate when we needed numbers to make a make a point, like getting someone’s gas reconnected if the gas company had disconnected them, for example.’

SPYCOP HN80 ‘COLIN CLARK’

Corbyn was questioned about his recollection of undercover officer ‘Colin Clark’ (HN80, 1977-82), who had infiltrated the Socialist Workers Party.

Corbyn admits he might have been confused when he said in his written statement about him selling the IMG publication Red Mole, and given that he did not recognise the photograph he had been shown, it might have been a case of mistaken identity. He did confirm that he remembered the name, however.

Thus, two and half hours in, the Inquiry had finally asked Corbyn about undercover policing, and that was the extent of it.

HUNTLEY STREET SQUAT

Corbyn, unprompted, brought up the issue of undercovers in the 1978 Huntley Street Squat.

In this case, two squatters, ‘Nigel’ and ‘Mary’ had come under scrutiny. During the eviction case the Under-sheriff of London admitted that the pair had worked for him, causing the judge in the case to get angry – not least because police agents had been helping build illegal barricades.

As a result, Corbyn invited ‘Sir John’ to extend the remit of the inquiry to the Under-sheriff of London. Mitting declined the invitation.

FINAL QUESTIONS

After another break, the hearing recommenced with the Inquiry asking Corbyn which other groups operated similarly to the IMG – in trying to ‘take over’ or control other campaigns.

The only example Corbyn gave was the International Socialists (later called the Socialist Workers Party) though added that, in comparison, the IMG was less controlling. He remembered anarchist groups were ‘very self-contained and wouldn’t want anyone interfering with them’ but then again:

‘the anarchist groups, to be fair, would just turn up at meetings and join into anything, so there wouldn’t be a consistent pattern with them.’

Rajiv Menon QC, Corbyn’s barrister, then took his turn, asking he had ever – during his 50 years of activism – taken part in:

‘any political activity that you consider was subversive in that it threatened the safety or well-being of the State and was intended to undermine or overthrow parliamentary by political or industrial means.’

Corbyn was categorical that he had not.

Menon next asked about the accuracy of an August 1976 Special Branch report [UCPI0000010850] into squatting.

Corbyn said in reply that many of the details are correct, but the report over-simplifies things and betrays the bias of its unknown author. Corbyn emphasised that the squatters movement was much more diverse than this document suggests.

Particularly, it implied anarchism was far more prevalent than he thought it was:

‘Although squatters became political, you know, people squatted through desperation.’

The document claimed that 80% of squatters did not want council housing, but Corbyn disagreed with this. He doesn’t know who wrote this, but thought the author had a particular anarchistic perspective. He also disagreed with the report’s statement that:

‘the general attitude towards the police is one of complete non-cooperation.’

Corbyn said it was common for squatters to deal with the police as a practical matter.

Finally, Menon noted that Corbyn is surprised by the dearth of material about the squatting movement from that era among what was provided to him.

Corbyn replied that he thought that undercovers would have visited, or even moved into, the squats. He wondered why there were no reports about these places included?

Corbyn concluded his evidence by questioning why he was spied-on for all these years.

Full witness statement of Piers Corbyn

Ernest Rodker

Ernest Rodker is now 83 years old and in ill health, so an edited version of his full statement was read by his son Oli Rodker.

The Inquiry asked Rodker for evidence concerning his campaigning activities over three decades from 1968, when the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) was founded.

The Inquiry has told him he was spied on by:

- Mike Ferguson (HN135, late 1960s-early 1970s)

- ‘Michael Scott’ (HN298, 1971-76)

- ‘Jim Pickford’ (HN300, 1974-76)

- ‘Phil Cooper’ (HN155, 1979-83)

- Jim Boyling (‘Jim Sutton’ HN14, 1995-2000)

- Andy Coles (‘Andy Davey’ HN2, 1991-95)

The Inquiry has given Rodker a bundle of about 53 vintage police documents relating to him. His first response is that it isn’t complete. He has been an activist since 1958, and it’s clear that his early arrests and monitoring fed into the SDS’ interest in him.

He has seen other, largely Special Branch, material which is in the public domain, which refers to him and his activism. He wants to see all the secret police files on him.

ANTI-APARTHEID ACTIVISM

‘White Area’ sign, apartheid South Africa

Apartheid was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 until the early 1990s. It categorised people into a hierarchy of racial groups, with whites at the top.

The laws segregated all areas of life, reserving the best for whites. It affected everything from education, employment and housing to which bench to sit on or beach people could visit. Most of the population was denied the right to vote. Sexual relationships and marriages between people of different racial groups were illegal.

Rodker was a committed campaigner against the racist apartheid regime in South Africa. He was active in the Stop The Seventy Tour (STST).

STST’s immediate and principal aim was to stop the white-only South African cricket team from touring in the UK in 1970. More broadly, its aim was to make a very strong political point that people representing apartheid were not welcome in the UK.

He was active in STST throughout its existence, from 1969 until it was disbanded in May 1970 after the cancellation of the tour.

The main tactic of STST and was to run onto cricket and rugby pitches to disrupt play.

He explained:

‘We sought to impress on the South African teams the fact that as an all-white team effectively promoting the apartheid regime they were not welcome. We wanted them to know the level of opposition there was to what they stood for and for them to reflect on whether it was the right thing, practically and ethically, to tour the UK.

‘We used all classic forms of non-violent direct action (NVDA), pitch invasions being the most prominent. We understood and sought to follow the well known principles of NVDA and civil disobedience learned from recent history such as the struggles for Indian independence by Mahatma Ghandi and for Black civil rights by Dr Martin Luther King.’

He refuted spycop Mike Ferguson’s March 1970 SDS report [UCPI0000008660] which describes STST as ‘militant’, especially given the connotations of that word in that era. STST’s campaign was avowedly opposed to committing violence against people, and only in favour of minor damage to property.

Rodker ran on to cricket pitches and sat down. He remembers being carried out by security or police and being kicked by spectators. He painted slogans on the walls outside Lords cricket ground, and even these were things like ‘stop the tour’ and ‘go home’ rather than anything more profane or aggressive.

DIRECT ACTION GROUP

Rodker was also part of a smaller anti-apartheid direct action group. This was not concerned with publicity but was a small, secret group directly inhibiting South African sporting tours. He can no longer remember what name the group had, but was clear about what it did:

‘These activities included things like going to a team hotel to carry out demonstrations there. For example, in the campaign against the white-only South African rugby team in 1969 I booked into a hotel, in an affluent part of central London, overnight where the team were staying. I sat among the players in the lounge eavesdropping on them and getting their room numbers.

‘While they were still in the lounge or having supper, I may myself have glued their door locks and certainly shared the room numbers with other campaigners, who did so…

‘On other occasions we waited outside the team’s hotels, for them to get on their coaches. We then got on the coaches as well and refused to leave. We had to be carried out.’

Rodker stressed the relative restraint of the campaign and, not for the first time at the Inquiry, we heard an activist turn the inquiry’s question about violence around:

‘We were not even carrying out wanton acts like going into the South Africans’ rooms and trashing their belongings. We were doing nothing on the scale of what the South African State regime was doing to its majority black citizenship under apartheid, systematically and repeatedly, under cover of the law…

‘We did not want our principled message to be confused by adverse publicity about violence. One factor in our thinking was that we wanted to set ourselves apart from the extreme of violence which the apartheid South African regime was showing to its Black citizens.’

Campaigning against sports connections with South Africa continued beyond the 1970s, in other forms, and he remained involved in those campaigns.

‘It is worth underlining that we were effective in the sense that, in the short term, the rugby team was, we learned, keen to stop the tour and wanted to go home, as a result of our actions. In the medium term we contributed towards the decision to abandon the 1970 cricket tour plans. And in the long term we contributed to the isolation of apartheid South African from international sport, a factor in its eventual downfall.’

ANTI-NUCLEAR CAMPAIGNING

Before his anti-apartheid campaigning, Rodker had been active in campaigning against nuclear weapons. Although it’s not mentioned in his testimony, Rodker was also a founding member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

He was involved in publicising, and took part in, the first of the famous Aldermaston marches which, from 1958 onwards, opposed nuclear weapons, particularly those stored at AWE Aldermaston military. He was a member of the Committee of 100, a British anti-nuclear group of the 1960s.

It had come to the attention not only of the media, but also the police, prosecutors and the courts as a result of its high profile campaign and campaigning methods, involving NVDA.

Rodker and many others in the Committee, including the philosopher Bertrand Russell, had been jailed for planning disruptive demonstrations and civil disobedience against US military bases in the UK. Some of the evidence used against them in court had come from covert police surveillance.

As the Inquiry is limited to events from 1968 onwards, it cannot examine anything from this era, no matter how relevant it may be.

MEMORIES OF SPYCOPS

In saying that he can’t remember the spycop Mike Ferguson, Rodker once again highlighted the unforthcoming attitude of the Inquiry. If he were told the name Ferguson used undercover, shown a contemporaneous photo or told about his interactions with him, his memory may well be jogged. But the Inquiry refuses to do any of these things and thus prevents itself from fulfilling its remit of getting to the truth about spycops.

Rodker said the movement was aware that it was likely to be spied on by both British and South African state agents, using infiltrators, phone taps and more, but they would not let this deter them.

Asked about three other officers – Phil Cooper who reported on him in May 1980 [UCPI0000013986], Jim Boyling who reported on him in 1997 [MPS-0742877], and Andy Coles who ‘authored some of these reports’ the Inquiry has released, Rodker drew a blank but once again highlighted that the Inquiry’s reluctance to give him (and other witnesses) photos of officers and other information that might jog his memory.

PAVEMENT COLLECTIVE

The Pavement Collective was a grassroots community initiative, based mainly around its publication ‘Pavement’ in South West London in the 1970s. It supported and encouraged campaigns by local communities on issues like housing, race, and employment. It challenged the council on issues of housing and redevelopment, which brought it into conflict with developers. It held demonstrations at Wandsworth Town Hall on the evenings of council meetings, and asked questions in the meetings.

The Pavement newspaper was sold in local newsagents and on streets. It was a very open group with public support from the likes of Michael Foot MP (former Labour party leader), Donald Trelford (editor of the Observer). It ran for about 20 years, and Rodker was on the editorial committee throughout.

The committee was about ten strong, and not secretive. A couple of members were in the International Marxist Group, who were of particular interest to the SDS, but Rodker says of the IMG as an organisation:

‘we were wary of them and I think it was clear to everyone that our politics and interests were not the same as theirs’

Rodker notes that spycop ‘Jim Pickford’ (HN300, 1974-76) infiltrated the Pavement Collective. He is listed as one of the 13 people present in the minutes of the editorial meeting of 18 November 1976 [UCPI0000033629].

Similarly – again, without mention from the Inquiry – there’s a document [UCPI0000033631], that shows another spycop, ‘Michael Scott’ (HN298, 1971-76), was involved with Pavement sales at the time he was infiltrating the Young Liberals (the youth wing of the Liberal Party, now the Liberal Democrats).

Why were spycops infiltrating the Pavement Collective? What exactly did they do there? Was Scott’s involvement connected with his infiltration of STST and arrest at the hotel demonstration on 12 May 1972?

BATTERSEA REDEVELOPMENT ACTION GROUP

Battersea Redevelopment Action Group (BRAG) was purely concerned with development of Battersea Power Station and surrounding area.

Rodker was active in setting up BRAG in about 1972 and remained active until it disbanded more than ten years later. The core group was no more than 10 in number, and there was no formal structure.

Mural c.1978 by Brian Barnes MBE (BRAG member & community artist) on the wall of Morgan Crucible factory, Wandsworth

They wanted to ensure that it wasn’t just turned into luxury flats but included affordable housing and community projects. They also opposed the council’s sell-off of social housing, believing that council developments and initiatives should be public and for the community, rather than private and for commercial interests. They leafleted, knocked on doors, and held public meetings.

And yet, for all this community-minded activity, there’s an SDS report on a BRAG meeting in December 1974 [UCPI0000015040], listing five members as extremists, including ‘Ernest Rodker (Anarchist)’, and other reports from 1975-77 [UCPI0000012093, UCPI0000012094, UCPI0000009594, UCPI0000011156] all of which were copied to MI5.

Rodker remembers suspicions in BRAG concerning one person did lead to a confrontation at a committee meeting and that person was excluded. Rodker wants the Inquiry to say if that person was a spycop. The Inquiry says Pickford also infiltrated this group.

Beyond that, he wants the Inquiry to tell him if any other undercover police officer, beyond those already named to him, were in the campaigns he was involved in. What information did spycops get from those campaigns? What was done with that information? Did any spycops attempt to disrupt campaigns? Did any spycops seek to have a genuine campaigner ejected from a campaign? What excuse is there for spycops being involved in the decision-making of small voluntary groups where every voice is significant?

VIOLENCE

Asked about violence in his campaigning, Rodker affirmed that there was a lot of it throughout his activist career, though perhaps not in the way that the Inquiry was driving at:

‘there was police violence against the Committee of 100. When there were demonstrations at the American embassy or a nuclear base, we were knocked about by the police when we were arrested or even moved from the base. Sometimes their physicality was quite severe. They dragged people by the hair, ‘accidentally’ stamping on people when trying to move them.

‘As to STST and the direct action group, I also experienced or witnessed violence. When I was involved in a demonstration in the centre of Lords cricket ground, I remember the stewards (or even members of the public) roughed us up unnecessarily when dragging us off the pitch’.

‘During the anti-nuclear campaign, in the late 1960s onwards, we occupied Grosvenor Square, Trafalgar Square, Whitehall and other sites in central London on various occasions. These were mass demonstrations, peaceful sit-downs with some campaigners linking arms and others using padlocks and chains to attach themselves to each other. It was clear to me that the police, frustrated by the task of having to remove us, lost control and used unnecessary force towards us. They punched, often surreptitiously; dragged people violently out of the way; stamped on people who were in the way of another person they sought to remove. This happened to me…’

Rodker said the police never took action against people who were violent to activists. Undercover officers have confirmed they were assaulted by uniformed police while undercover. They saw violence against genuine activists and yet they didn’t bother to report it or, if they did, nothing was done.

‘Looking back, on the basis of what we know now, it seems logical to conclude that there was a policy of allowing aggressive and violent behaviour towards activists to go unchecked.’

FOR SPYCOPS, THE PERSONAL IS THE POLITICAL

Attention turned to two 1976 Special Branch reports containing very personal information about the birth of his son [UCPI0000012246] and a health condition of his [UCPI0000010719].

Rodker confirmed that, whilst not secret, these details would only have been known to personal friends and family. He said it was not only sinister that the reports were made, but also that we are able to see these reports at the Inquiry because they are still held in MI5’s files nearly 50 years later.

Rodker said that it underlined his desire to have the Inquiry obtain and hand over all information all spycops have recorded and stored about him, at any point in his life. Which officers did this? What did they do to get the information? What was the information used for?

THE STAR & GARTER ARRESTS

On 12 May 1972, Rodker took part in action at the Star & Garter Hotel, Richmond, to prevent the British Lions rugby team leaving for the airport to go on a tour of apartheid South Africa.

Though his memory has faded, Rodker accepts that he was the main organiser, and that the descriptions in the police reports are broadly accurate [MPS-0526782, MPS-0737087, MPS-0737109, MPS-0737108].

Spycop Michael Scott was part of the group, including the planning meeting at Rodker’s house on the day. He disputes Scott’s claim to have found out because Peter Hain’s mother told him on the phone. Rodker knew Mrs Hain well, she was security conscious and highly unlikely to have disclosed such sensitive information. It’s more likely that he found out another way and is lying in his report.

The objective was to make the players miss their flight. Skips were ordered to the hotel, cars were parked in the way, and individuals blocked the coach.

Rodker submitted a letter to the Inquiry that had been written to him a month later by a friend, attached to which was what his friend calls ‘my rather uninformative account of the events at the hotel’ [UCPI0000033628]. However, it is now vital evidence from our perspective as describes the incident, his role in it and he also describes what spycop ‘Mike Scott’ did.

THE TRIAL

Fourteen protesters were arrested and prosecuted for obstruction of the highway – including Scott. They were convicted. Scott had stolen the identity of a living person for his fake identity, so received a conviction for that real person.

It’s almost certain that Scott was party to the defendants’ discussions of how to defend their case, and what their lawyers thought. This breaches lawyer-client privilege.

More to the point, it meant that the trial was unfair. In a criminal case, the prosecution must give the defence all relevant evidence. Not only were Scott’s reports withheld, but the court was not given his testimony. Coming from a police officer, it would have been very credible indeed. It could have cleared up the disputed issue of whether the protest was blocking the public highway as alleged, or whether it was on the hotel’s private land.

Scott’s managers told him to go ahead with the trial under his false identity. Right from the first question in court, when he was asked his name, he was lying.

The police reports show no concern at all about deceiving the court and orchestrating a miscarriage of justice, only for ‘potential embarrassment to police’ if it became known that a spycop was involved.

Rodker sees this as part of a pattern that would repeat:

‘The failure to view activists as individuals with their own legitimate rights and interests and the decision to place those second to the unfettered gathering of information on them may be a precursor to some of the more gross abuses of activists that, I note, happened in later periods of undercover policing of campaigners.’

RELEASE THE FILES

Concluding, Rodker returned to the fact that he was spied on and demonised long before the SDS was founded in 1968, as the SDS themselves describe in a May 1972 report [MPS-0526782]. It describes the 14 people arrested on the Star & Garter action as:

‘anarchist-orientated extremists under the control of Ernest RODKER’. This man has been a thorn in the flesh for several years now, having had no fewer than 14 court appearances prior to 1963 for offences involving public disorder. He was considered to be a menace at the time of the protest demonstrations taking place in this country concerning the Springboks rugby tour in 1969 and the Stop The Seventy Tour in 1970.’

Rodker called for the release of all his secret police files, not only for his own benefit but also to correct false information and allow him to comment and contribute fully to the Inquiry.

The Inquiry Chair, Sir John Mitting, said that the Inquiry had done its best to give Rodker all relevant documents, but it doesn’t cover all of Special Branch, just the SDS. This contradicts the Inquiry’s Terms of Reference which state:

‘The inquiry’s investigation will include, but not be limited to, the undercover operations of the Special Demonstration Squad and the National Public Order Intelligence Unit.’

Mitting then indicated that he would be referring the Star & Garter incident to the Inquiry’s panel that is reviewing likely miscarriages of justice.

Full written statement of Ernest Rodker

<<Previous UCPI Daily Report (27 Apr 2021)<<

>>Next UCPI Daily Report (29 Apr 2021)>>