UCPI Daily Report, 5 May 2021

Tranche 1, Phase 2, Day 10

5 May 2021

Summary of evidence:

‘Gary Roberts’ (HN353, 1974-1978)

‘Geoff Slater’ (HN351, 1974-1975)

Introduction of associated documents:

Richard Clark (‘Rick Gibson’ HN297, 1974-76)

Evidence from witnesses:

Richard Chessum

‘Roger Harris’ (HN200, 1974-1977)

The Undercover Policing Inquiry hearing on 5 May began with summaries of evidence from ‘Gary Roberts‘ (HN353, 1974-78) and ‘Jeff Slater‘ (HN351, 1974-75).

Neither is giving any evidence in person. This goes against the wishes of non-state core participants, who believe all undercovers should give live evidence and have their evidence examined by Counsel.

‘Gary Roberts’ (HN353, 1974-1978)

This officer’s cover identity was stolen from a deceased child.

INTERNATIONAL SOCIALISTS & INTERNATIONAL MARXIST GROUP

Roberts was deployed undercover in the spring of 1974, targeting first the Finsbury Park branch of the International Socialists (IS). He then switched to the South East London branch of the International Marxist Group (IMG). Within the IMG, Roberts had another pseudonym – a so-called ‘party name’ of ‘Gary Shopland’.

His involvement with the IMG began in late 1975, and he remained a member of the group until his deployment ended circa June 1978. Roberts thinks that he may have been tasked with infiltrating the IMG as a replacement for HN338.

STUDENT AT THAMES POLYTECHNIC

To further his cover story, Roberts became a student on a degree course at Thames Polytechnic attending classes and taking exams over the years. He became Vice President of the Student Union there. The course was paid for by the Metropolitan Police, although he never completed the degree.

MISSING REPORTS

Battle of Lewisham plaque, erected on New Cross Road, 2017

It is likely that of the reports relating to IMG meetings and members in South East London, some were written by HN338 and others by Roberts. There is some dispute about this.

Roberts has pointed out that he has not been shown any reports filed by him for the period December 1977- June 1978. He attended many large demonstrations, and reported on public order situations, but these reports seem to be missing. He says he witnessed public disorder at clashes between right- and left-wing groups.

In particular, he recalled the counter-demos mounted by anti-fascists against National Front marches in both Wood Green and Lewisham in 1977. He also recalled being charged by mounted police at a demonstration.

There is a report of him attending one demo during the summer of 1975 – a small National Abortion Campaign protest [UCPI0000012738]. This included a speech by Labour MP John Fraser which was also reported. He does not recall any property damage.

COUNTER PROTESTS AGAINST FASCISTS

He claims in his statement that IMG members, having learned of the location of the Wood Green march in 1977, scouted the route to find good places to throw missiles at the fascists.

Also in his witness statement, he recalls his attendance at the counter-demonstration thinking that the police had left too great a gap between officers as they escorted the National Front demonstrators. This had enabled the IMG to confront the marchers, resulting in violence.

Somewhat surprisingly, not mentioned in summary evidence read out by the Inquiry, in January 1977 it seems Roberts may have attended the initial meeting of the All-Lewisham Campaign Against Racialism and Fascism in his capacity as vice president of Thames Polytechnic Students Union. The group contained representatives from the IMG, the Anglican Church Council, the Labour Party, the Communist Party, and Black and Asian groups [UCPI0000017686].

‘HOOVER’

Of his reporting style, he said:

‘I would hoover up everything.’

This included the political content of meetings, as he knew the Security Service (MI5) found this interesting.

This is borne out by his reporting on the 1976 IMG National Conference [UCPI0000021343]which almost exclusively focuses on the debates between different ideological groups within the IMG. The value of this report is indicated by the fact he received a telephone message from MI5 and a Deputy Assistant Commissioner’s commendation.

Roberts assessing the potential for subversion on the IMG says they:

‘were strong in words, but in hindsight, I think they were not really likely to act on them.’

On other witnesses in the Inquiry, he does recall ‘Mary’, who appeared in several of his reports, as well as Richard Chessum [UCPI0000008223].

Piers Corbyn is also mentioned, including in relation to his election campaign for the Greater London Council, which is an example of spycops targeting the democratic process [UCPI0000008229].

Roberts says that he did not engage in any criminal activity, did not have any intimate or sexual relationships with activists, and did not join a trade union, although there he did make one report on Greenwich Trades Council [UCPI0000009380].

Summary of Roberts’ evidence by Counsel to the Inquiry

Written statement of ‘Gary Roberts’

‘Geoff Slater’ (HN351, 1974-1975)

Special Demonstration Squad officer HN353 used the name ‘Jeff Slater’ or ‘Geoff Slater’ to infiltrate the Tottenham branch of the International Socialists (IS) for under a year (1974-75).

His fake identity was stolen from a deceased child.

Before his deployment he spent time in the SDS back office but was given no formal training or any specific guidance about what information to collect.

He had cover employment at a car dealership, and a cover address which he occasionally visited but did not stay overnight at. Slater was also provided with a cover vehicle and documentation.

The first known report from Slater is dated August 1974 [UCPI0000007918] and the last is March 1975 [UCPI0000006971].

Slater does not remember enough to comment on these reports. He says he did not type them up himself. Nor does not recognise any of the reporting he has been shown and does not believe that he was the author of any of them, except two.

UNSPECIFIED VIOLENCE

Slater says he attended various demonstrations to initiate contact with activists. He recalls that IS were viewed as a ‘subversive’ group who were:

‘organising to bring about the fall of the State and they would use any means available to achieve this, including violence.’

He alleges that IS members used violence, though says he never took part in any himself. He also claims to have witnessed many incidents of major public disorder, which included police officers being assaulted. However, he does not cite any specific instances to support his claim.

A report from November 1974 mentioned IS becoming involved in industrial action [UCPI0000015056]. However, Slater denies that he became involved with any trade unions during his deployment.

According to one report, dated January 1975, he became the official Socialist Worker Organiser of the Tottenham branch, [UCPI0000012014].

Some of the groups he spied on were campaigning for racial and sexual equality [UCPI0000014964]. His reports also cover global political issues, the Irish situation, plans for protests and educational classes, and personal information about group members.

Slater also stated in his witness statement, whilst having no recollection of the contents of reports (including [UCPI0000014961]), with regard to Irish matters he states that he was:

‘instructed to report on any matter relating to the IRA and Irish Troubles more generally which were of relevance to Special Branch at the time.’

He says he did not get particularly close to any of the activists or form any sexual relationships during his relatively short deployment.

BABYSITTER & BIRTHDAY PARTY SPY?

The babysitting rota of the North London District of IS was shared in a report dated 8 January 1975 [UCPI0000012021]. This list shows ‘Geoff Slater’ as volunteering for this. It is unknown if Slater ever took his turn on the rota, but it would obviously be a concern to any parent to discover that they left their child with an imposter.

Another report attributed to Slater (wrongly, in his view) was on an IS member’s birthday party [UCPI0000006850].

EXIT

Slater’s deployment ended in the spring of 1975. This was at his request, as he found the work to be ‘debilitating and exhausting, both mentally and physically,’ and did not think he was suitable for it. He spent some time working in the SDS back office after this doing clerical work.

Written statement of ‘Geoff Slater’

Richard Clark (‘Rick Gibson’ HN297, 1974-76)

The inquiry mentioned that it was releasing documents relating to undercover officers ‘Jim Pickford‘ (HN300, 1974-76) and ‘Desmond/Barry Loader‘ (HN13, 1975-78). However, as Thursday’s hearing will include summaries of statements from both men’s widows, the COPS daily reports will deal with their respective material in one go then.

The Inquiry also mentioned its release of materials about SDS officer Richard Layton Clark (‘Rick Gibson’ HN297, 1974-76).

Clark spied on this hearing’s next witness, Richard Chessum, and ‘Mary‘, among others.

He was deployed into Goldsmiths College in December 1974 by the Special Demonstration Squad.

He was 29 years old, married with children, and had been a police officer for five years. He stole the identity of a deceased child, Richard Gibson, as the basis for his undercover identity. He enrolled at the Goldsmiths College on a Portuguese language course.

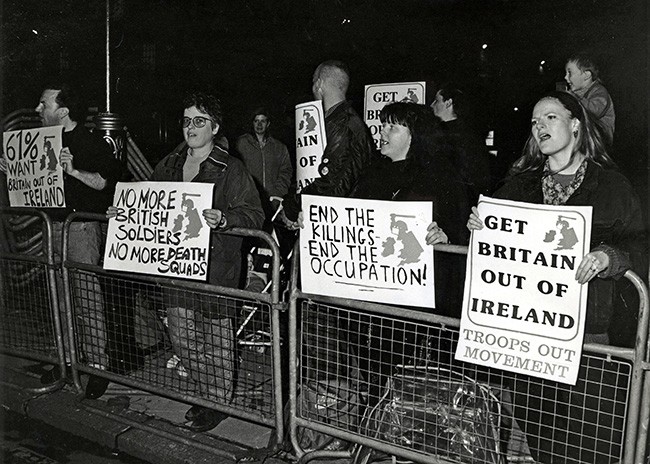

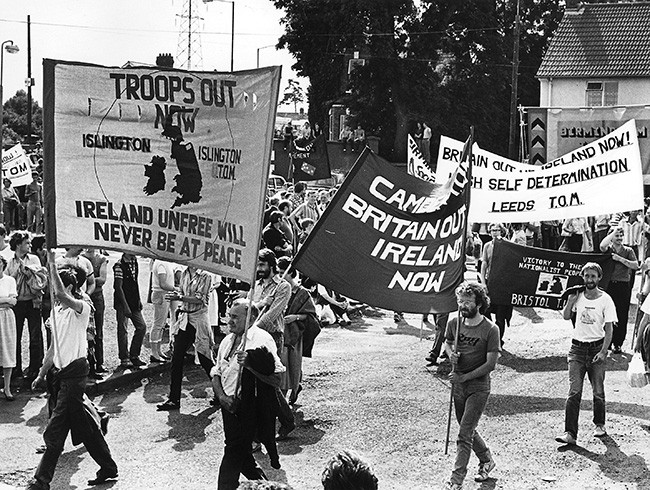

Clark’s target was the Troops Out Movement. It’s an interesting target from the perspective of this Inquiry,because it did not fit with the stated aims of the SDS. The Movement posed no public order risk at all.

Its aims were publicly stated and straightforward:

i. Self-determination for the people of Ireland and

ii. the withdrawal of British troops from Northern Ireland

Their methods included lobbying Members of Parliament, drafting alternative legislation and raising awareness, with occasional low-key demonstrations, talks and film-screenings.

Clark is also known to have reported on the Free Desmond Trotter campaign in May 1975.

His deployment ended in late 1976. By December, he had been posted to another area of Special Branch, ‘S Squad’.

Clark was promoted in 1986, to the rank of Detective Inspector. He received other medals and awards before finally retiring from the police in 1998.

He has since died, so we will not be hearing any evidence from him, only from those who he spied on, and some of his erstwhile colleagues.

For a more detailed account of Richard Clark’s extraordinary deceit as a spycop, see the opening statement to the Inquiry from James Scobie QC.

Richard Chessum

The Inquiry’s next witness was a non-State core participant, Richard Chessum, who was part of the Troops Out Movement (TOM). He was spied on by a number of spycops, including Richard Clark (‘Rick Gibson’ HN297, 1974-76). Clark is now deceased.

Chessum and ‘Mary‘ provided the Inquiry with an opening statement, and Chessum has provided his own written witness statement as well.

POLITICAL OUTLOOK

The overarching aim of Chessum’s political activity over a lifetime has been to contribute to a better world. He was a Methodist lay preacher, involved in the Labour Party and in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) before he moved to London in 1968 and got involved in the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign (VSC) and then the Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM).

Stop The Seventy Tour protest, Lords cricket ground, 1970

He joined in with the anti-apartheid Stop The Seventy Tour (STST) action at Oval cricket ground in 1969 – a pitch invasion carried out with the intention of creating an opportunity for dialogue with the all-white South African team.

He enrolled at Goldsmith’s College in 1970 and, because there was no Socialist Society there, he set one up. He recalled people’s disillusionment with the Labour government of the time. The Socialist Society held open weekly meetings, and advertised its activities to both students and staff. Among the people he recruited from his stall was the woman who later became his wife.

Chessum also joined the Anti Internment League, which opposed the internment without trial of republican prisoners in Northern Ireland. In 1972, he organised a demonstration after ‘Bloody Sunday’, when British troops killed 14 people on a civil rights march in Derry. He got more active about the situation in Ireland due to an Irish house-mate at the time prompting him to do so.

He eventually joined the International Marxist Group (IMG) in 1972, having deliberately avoided joining any of the left-wing groups that existed up till that point. He left within a year, preferring ‘to be on the open sea’ rather than stuck in a small ‘political goldfish bowl’.

Though his membership of the Labour Party had lapsed when he moved to London, he later re-joined. He says he felt very ‘at home’ within the Labour Committee on Ireland, and became its press officer.

Chessum is still politically active now, with a local group set up to assist asylum seekers and refugees, offering company and an opportunity to learn English. This group has fought against both destitution and racism. It now has over 300 volunteers and has become, in his words, ‘a substantial presence in the city of Sheffield’.

SPYCOP ENTERS THE SCENE

In 1974, Chessum was elected to the Students Council at Goldsmith’s. He had been a member of the Anti Internment League (AIL) in the past, and he supported the aims of the Troops Out Movement (TOM).

TOM was formed in West London in September 1973 by Irish solidarity activists, trade unionists, socialists and Irish people living in Britain. It was a campaigning organisation committed to bringing an end to British rule in the north of Ireland.

TOM had two stated aims. First, it campaigned for the withdrawal of British troops from Ireland. Second, it campaigned for self-determination for the Irish people.

TOM also campaigned around related issued including justice, policing, equality, demilitarisation, employment discrimination, cultural rights and the Irish language.

Chessum explained how he came to meet the spycop ‘Rick Gibson’. He was contacted by the national TOM office, who told him a Goldsmith’s student had been in touch asking if there was a TOM branch in South East London.

Chessum decided to set one up at Goldsmith’s, and met with ‘Gibson’ in the student union bar to discuss this plan. He thinks this meeting would have taken place in December 1974, just before the holidays.

The Inquiry has found a Special Branch report of a Socialist Society meeting which took place at Goldsmith’s in January 1975 [UCPI0000012122]. Titled ‘Why a Troops Out Movement?’, it was attended by 45 people.

STARTING A GROUP TO SPY ON

The main speaker was a former paratrooper named McConnell, from the North London branch of the TOM. Chessum proposed the formation of a SE London TOM branch and an informal meeting was planned for the following week.

That informal meeting in Februaty 1975 was the subject of the next report [MPS-0728678] we saw. There was a very low turn-out, with only two people (presumably Chessum and Gibson) present at the start. They were later joined by three IMG members (who only came along because their own class had been cancelled that night). One of them was ‘Mary’. He knows that Mary remembers meeting ‘Gibson’ for the first time at a political stall.

This next Special Branch report [MPS-0728205] is all about Richard Chessum, detailing his personal life and political activity, and even his sister’s move to York.

The Inquiry then took Chessum through a series of reports that, for the most part, demonstrate just how small the group’s meetings were, and how quickly the undercover officer made his way up through the ranks of the TOM.

The Inquiry then took Chessum through a series of reports that, for the most part, demonstrate just how small the group’s meetings were, and how quickly the undercover officer made his way up through the ranks of the TOM.

These included a report [MPS-0728701] about the inaugural meeting of the SE London branch on 12 March 1975. Numbers were disappointingly low at this meeting too. Lots of left-wing groups and trade unions had been invited to come, but most hadn’t. Chessum chaired the meeting. The only invited speaker was a senior figure in TOM, Géry Lawless.

The group met again a week later, on 18 March, as detailed in the next report [MPS-0728710]. This meeting was attended by just 11 people. Elections were held, with Rick Gibson being elected Secretary of the new branch. It was also agreed that he and Chessum would be sent as delegates to the ‘Liason Committee Conference’ that weekend.

Chessum explained that, at the time, he and others were coming up to their final exams, so they didn’t put themselves forward for the role of Secretary as they knew that it would require quite a lot of work. However Gibson volunteered himself, and the use of his car.

From the perspective of intelligence gathering, it was an interesting position. It gave Gibson access to the personal details of every member.

Prospective members would contact the TOM Secretary in the first instance, giving Gibson a chance to assess them as they joined the group, and quite possibly influence the process. At first, the group met at Chessum’s home. Later they met at Charlton House.

The group organised events like a picket outside the house of local MP (and Under Secretary of State for Northern Ireland) Roland Moyle. Chessum recalls being invited in for tea and biscuits. At the time he assumed people present were colleagues of the MP, but now he wonders if they were part of the State, as they did ask the group lots of questions about their personal political views.

However, Gibson’s report differs from Chessum’s memory, stating that Moyle was present that day but refused to speak to the demonstrators, and that nobody was invited inside the house at all.

A meeting at Charlton House on 21 May 1975 was probably the first public meeting of the new TOM branch outside of Goldsmith’s. The report [MPS-0728681] says it was a success, with about 45 people attending thanks to ‘good local publicity’, and credit for this outreach is given to Chessum and Gibson.

Gibson is one of the few officers who, in his reports, wrote about his own activities as if he is one of the members of the group. He had a habit of including himself on the list of attendees, with his Special Branch registry file number added.

We are left with the impression that Gibson put a lot of effort into getting people to come to these meetings, and then when they did, he would report their attendance to Special Branch.

The next report [MPS-0728668] is of South East London TOM members attending a Labour Party meeting at Alderwood School in June 1975, and questioning the Labour candidate about his views on the Irish situation:

Chessum explained that there was no public disorder:

‘The objective would have been to try and persuade people in Labour to support us’

Unsurprisingly, the Inquiry asked Chessum about the legality of TOM’s actions, despite the reports showing that the group supported parliamentary democracy to such an extent that they lobbied MPs to try to get them onside.

Chessum was unquivocal; TOM did not carry out or promote illegal acts. There was certainly no direct relationship between TOM and the Provisional IRA. He suspects that a September 1975 report about a visit to Northern Ireland [UCPI0000007665] was inaccurate – members of the TOM may well have met with Sinn Fein, the political party, but not with the IRA, which was a highly secretive organisation.

FRIENDSHIP

Chessum developed a friendship with Gibson. The two men spent time together, not just in the pub after meetings, but they also attended some Charlton Athletic football matches together. Chessum also recalled meeting up on the Woolwich free ferry at lunchtimes after Gibson had begun (he said) working near him in that part of London.

He thought that they bonded over their distaste for sectarianism, and found it relaxing to discuss things freely with someone who wasn’t a zealous member of any particular group. This is a practice known as ‘mirroring’, reflecting back someone’s perspective in order to create a closeness. Other spycops have said they were trained to do this.

There are a number of reports on the TOM, including meetings of its London Coordinating Committee and its national secretariat, and their plans to hold a demonstration and rally about Bloody Sunday, which was commemorated every year.

The next report [MPS-0728777] is about one such meeting, which took place in January 1976. The group had planned for a rally on 1 February, and booked the Hammersmith Palais for it, but this booking had just been cancelled on them at fairly short notice. Chessum recounted how the police at the time used to go round pubs encouraging landlords not to allow political meetings on their premises.

Another report from January 1976 [MPS-0728774] shows TOM’s press officer being criticised for inactivity, and the group deciding to replace him with a Press Committee. Three people, including Gibson, were then elected to this new committee. The committee’s first task was to prepare a statement about the Hammersmith Palais cancellation and the State’s repression.

In hindsight, Chessum is concerned that an undercover officer got involved in this kind of task, as the wellbeing of the TOM was clearly not his priority.

PLOTTING AND SCHEMING

During this era, sectarian groups, like Workers Fight and the Revolutionary Communist Group, were often disruptive at TOM meetings.

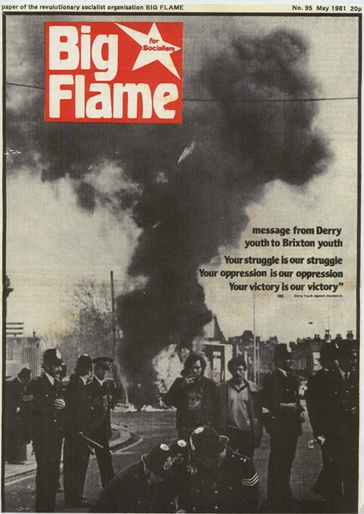

Chessum recalled that to counter the influence of these groups, an informal alliance had formed between Géry Lawless, other ‘independents’ within TOM, and members of Big Flame.

Chessum recalled that to counter the influence of these groups, an informal alliance had formed between Géry Lawless, other ‘independents’ within TOM, and members of Big Flame.

Gibson went on to higher positions within TOM nationally. We can see him being described as a ‘London Organiser’ and a member of the national Secretariat in this report from early 1976 [MPS-0728777].

Chessum says he was approached by Lawless and by a member of Big Flame about becoming a London Organiser himself, but in the end it was Gibson who filled that role.

TOM’s South East London branch elected two delegates for the Coordinating Committee. Both Gibson and Chessum stood for these delegate positions. Workers Fight and the Revolutionary Communist Group both turned up en masse to the meeting where this election took place.

The sectarians were on one side, Rick and Richard on the other. They felt sure that the votes would go one of two ways – but what happened was that Gibson and one of the sectarians were narrowly voted in to these two positions. Chessum reckons this must be because Gibson voted for himself, but not for Chessum.

Having now reached the national level of the TOM, Gibson would have had access to a great deal of information about their plans, members and about any legal advice they ever received – for instance about the Hammersmith Palais cancellation.

Some serious, internal, personal criticisms are revealed in a report from a Blackpool fringe meeting from May 1976 [UCPI0000009684]. Chessum explained:

‘I understand that one of the people attacked was someone called Sean McKavanagh [founder and leader of Workers Fight], a bitter enemy of Lawless.’

He went on to suggest that Gibson may well have done this in order to curry favour with Lawless. It is obvious that Gibson was now trusted by Lawless and others, and given a lot of responsibility.

BIG FLAME

Big Flame had been described as ‘libertarian Marxists’ and the Inquiry asked Chessum to explain what that meant. He said they differed from the more authoritarian, dogmatic groups found on the left – they didn’t have a strict ‘party line’ and were more open to discussing different viewpoints.

Big Flame had been described as ‘libertarian Marxists’ and the Inquiry asked Chessum to explain what that meant. He said they differed from the more authoritarian, dogmatic groups found on the left – they didn’t have a strict ‘party line’ and were more open to discussing different viewpoints.

There were ‘lots of feminist women’ in Big Flame, and Chessum said he thought they probably felt more comfortable in this more egalitarian, less sectarian environment.

Chessum began attending reading nights organised by Big Flame, and as soon as Rick Gibson found out about that, he asked if he could come along.

He recalled one incident where Gibson was due to ‘take a turn’ addressing the group on a topic of his choice, but performed badly. His notes were of no help, and he completely clammed up. Chessum now thinks this should maybe have been an indication that Rick wasn’t really a committed person’.

In the meantime, Gibson appeared to have become convinced that Géry Lawless was too powerful within TOM. Gibson convened a meeting at his undercover flat to with some members of Big Flame to organise an internal coup to put an end to Gery Lawless and his ‘leadership clique’, as detailed in his Special Demonstration Squad reports of August [UCPI0000010775] and September 1976 [UCPI0000021388].

Chessum remembers that he found it strange to hear that Big Flame felt able to ‘take over’ TOM at that time. Seeing that Gibson was heavily involved in this internal situation, he can’t help but wonder if Gibson was deliberately responsible for the breakdown of the alliance.

SPYCOP SUSPECTED

Chessum knew Gibson had sexual relationships, first with his friend ‘Mary’ and then with her flatmate, and says that was general knowledge at the time. He only found out later he had also got intimately involved with at least two Big Flame women, one of whom he had a more long-term relationship with.

In the potent opening statement made to the inquiry last week on behalf of Richard Chessum and ‘Mary’, their lawyer explained how Gibson used these relationships to ingratiate himself into the groups he infiltrated, and the role they played in his activist career.

When Gibson applied to become a member of Big Flame, the group carried out some background checks on him; they were suspicious of his motives and his over-eagerness. He told some people that he planned to move to Liverpool, a city with a very active Big Flame group, as well as a large, well-connected, Irish community.

We don’t know exactly what else raised their suspicions, but Chessum recalls that when Gibson first turned up and got involved with TOM, activists had wondered why he was so invested in campaigning about Ireland as he had no obvious personal connection or Irish background. They even discussed the possibility of him being some kind of spy right at the start, but decided he wasn’t one.

Did he accidentally tell different women different things, and they then compared notes and spotted the discrepancies in his cover story? ‘Mary’ said he didn’t share any contact details with her, was often very hard to reach, and she knew very little about his background. There was also the failed presentation at the reading night that exposed a lack of political insight.

Richard Chessum got married in July of 1976 and so was away on honeymoon in Cornwall. By the time he returned to London, Gibson had been exposed, and had disappeared.

SPYCOP UNMASKED

Big Flame had told Gibson that they always carried out background checks on prospective members, and gone to work on him. They had got hold of his supposed date of birth and checked for the birth certificate at the government registry at Somerset House. They then went to the local records office where Rick Gibson had been born, where they discovered his death certificate.

Now they knew he was not really Rick Gibson, but had no idea who he really was. They thought he might be working for Special Branch or MI5. He had mentioned being employed at a campsite, so Big Flame folk went to visit it. Upon discovering it was run by an ex-army guy, they wondered if their spy had military connections.

Many of the details he provided for his ‘relatives’ were for people living in port towns, so this made them wonder if there was a link to Special Branch. They even wondered if he was a fascist of some kind.

They told Gibson that they needed to know more about his background, but none of the details he gave of family members or the school he went to checked out. He kept inventing new stories to explain it away, but he failed to convince the group.

This intense process didn’t deter Gibson from wanting to join, so Big Flame took more drastic action. They invited him to meet them in a pub and then spread out all the evidence they had gathered. ‘He looked as though he was going to cry’, Chessum was told about this incident.

He came up with one last story and gave them a phone number of the office where his brother was supposed to work. It was another lie. When they went to check his flat, they found that he had done a midnight flit, and it was empty.

Chessum was told about all this by someone from Big Flame. He was shown the dossier of evidence that had been compiled. This was later sealed and hidden away by the group. It included the birth and death certificates, and a letter Gibson had left behind for the woman he had the more serious relationship with. Chessum was told to keep the story secret, and he did, for many years.

After this, he met with Mary and her flatmate, and told them what he had seen. He says they were shocked but not surprised. They had already discussed the possibility of him being some kind of police officer. They had noticed his habit of never staying overnight, and wondered if this was because he had a wife to go back to.

LEGACY OF DECEIT

Chessum now wonders to what extent Gibson was sent to target him personally. He worked in Woolwich in those days. Gibson suddenly found a job nearby, and they would sometimes meet up in their lunch breaks. Gibson’s supposed workplace was nearby, and he and talked about an office behind a bank.

Chessum remembers visiting him there at least once, and seeing other people at work, and files in the rooms. After Gibson’s disappearance, we went to take a look, and found the office completely empty, with no traces of Gibson or anyone else.

Workers at the bank gave him a phone number to try. He was put on hold for a very long time, and then told that Gibson no longer worked there.

Chessum was not surprised that the spycops were interested in the political activity he was involved in, but he was surprised by the sheer volume of personal information being recorded and retained about him and others:

‘I find it sinister, actually’

Afterwards, he found it hard to find employment, not just in his academic area of expertise but even at a postal sorting office, and suspects that he was ‘blacklisted’ in some way due to his political activity, especially due to the connection with Northern Ireland.

The Inquiry’s Chair,, Sir John Mitting, thanked Chessum for providing such quality evidence, and for putting him right about his earlier assumptions. Mitting has previously described Gibson’s deployment as ‘unremarkable’ but now sees that this was not the case at all.

Let’s hope that Mitting continues to learn from the evidence of non-State core participants and witnesses, and everyone who was spied on by these disgraced spycops units rather than trusting the police to provide answers.

Roger Harris (HN200, 1974-1977)

The Inquiry’s next witness was Special Demonstration Squad officer ‘Roger Harris’ (HN200) who was deployed between April 1974 and October 1977 to infiltrate the Twickenham branch of International Socialists (IS).

IS later became the Socialist Workers Party, but before that the Twickenham branch was suspended from IS – during Harris’ deployment – and most of its members went on to join the Workers League.

Harris joined the Metropolitan Police in the 1960s and was based in central London. This meant he spent considerable time policing demonstrations.

He thinks demonstrations presented a lot of public order problems for the police in the 1960s, and much less in the 1970s. He is convinced that this was due to the work of the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS), noting that it was set up in 1968.

He transferred from uniformed duties to Special Branch, working in ‘C Squad’ which gathered intelligence on left-wing groups. As part of this work, he grew a beard and longer hair in order to fit in at meetings.

Harris became aware that the SDS existed – though not by name – when he recognised Special Branch officers among activists. All the same, he says the SDS was not an ‘open secret’ in Special Branch.

He was recruited into the SDS by officer Detective Chief Inspector HN294, who had been undercover 1968-69, and was running the unit by the time Harris joined.

TARGETING INTERNATIONAL SOCIALISTS

Seemingly trying to illustrate the benefit of SDS tactics, the Inquiry showed a Special Branch report of Harris’ [MPS-0739315] from October 1971, before he was in the SDS.

It describes a meeting of the Hackney & Islington branch of the IS. This took place in the Rose & Crown pub in Stoke Newington. The report lists 21 people as attending, to discuss matters arising from a recent conference in Skegness.

It may sound unworthy of police attention, but the report shows Harris was among a total of nine Special Branch officers observing the meeting from the bar, having failed to gain entry to the back room it was held in. The police collected details and descriptions of those who attended, including their car registrations. The SDS would have been able to get more information than that, we were told. Though why they’d need to is another question – one the Inquiry did not ask.

In his witness statement, Harris said he felt fortunate being sent to infiltrate the IS, as if he had been sent into a Marxist group he would probably have quit. In person, he elaborated:

‘IS was similar to a lot of my friends, I like to have a sort of light-hearted attitude to life, and from what I heard these Marxist groups were very serious’

Harris found many of the views held by IS were reasonable positions that a police officer could agree with. This is somewhat refreshing, given how many other undercovers have sought to exaggerate the supposedly dangerous or subversive nature of the group.

TRAINING

Harris was not provided with any formal training when he joined the SDS in 1974, though was an experienced Special Branch officer. He spent six months in the SDS back office, and picked up more about the work of the unit as he went along. This included attending SDS safe house meetings prior to being deployed, to help prepare for what he was likely to face and to familiarise himself with the way the unit worked.

STEALING AN IDENTITY

The Inquiry has treated us to a number of euphemisms for spycops stealing a dead child’s identity – ‘adopting’, ‘using’, and ‘relying on’ it. It was straightforward identity theft. Just because it was police doing it doesn’t mean we should downplay it with softer language than anyone else would get for doing the same thing.

Harris stole the identity of a deceased child as the basis of his undercover identity, as this was standard practice, taught by his superiors.

‘I was a bit upset and I actually said “why is that necessary?”… it wasn’t something that sat comfortably with me. The reason I was given was that we needed to have a birth certificate to obtain subsequent documentation for myself, such as obtaining car insurance, and that sort of stuff.’

He was not told that this was a relatively new technique, and that it hadn’t always been used by all officers in the unit.

He went to the birth registry at Somerset House with a colleague. He chose the name of a teenager rather than a baby, as he thought the birth and death certificates would be further apart in the records and less easy for someone from IS to find if they were checking up on him.

Did he ever consider the possibility that the family of the dead child might find out?

‘that was why I was not happy with it in the first place’

POLICE CRIMINALITY

Unlike most of his colleagues who have been asked, Harris says he did see the Home Office Circular [MPS-0727104] that expressly forbids undercover officers from participating in serious crime, or from being involved in anything that is likely to lead to a court being deceived. It’s notable that the officers who did lie to courts have no memory of ever hearing the unequivocal instructions of this document.

Harris specifically remembered that he and his colleagues were given a special phone number so if they were arrested and taken into custody they could give that to someone at the police station and be released. He doesn’t recall anyone ever using it.

PREPARING FOR INFILTRATION

Harris was tasked to infiltrate IS by DCI Derek Kneale. Harris was replacing ‘John Clinton’ (HN343, 1971-73) in the organisation, and the two met to discuss the handover.

Like most of his colleagues, Harris doesn’t think he had any training or guidance on the limits of intrusion into personal lives, nor on the prospect of sexual relationships with people he spied on.

WHY SPY?

Asked to define subversion, Harris declared:

‘if you have an established system like we have in this country, we’re a democracy, and somebody tries to interfere with that by surreptitious means, I call that subversive’

Having said IS had subversive objectives, he conceded they were more seeking to interfere with or disrupt, rather than fully overthrow the system.

Asked how they sought to do it, he replied:

‘I can’t recall a particular incident’

Harris said he did not see any violence while undercover. Though he qualified it slightly with an anecdote that did not actually describe anything violent:

‘there was only one that nearly got violent, and that was the closest we came… it never actually came to violence. We came to a face to face – two cordons, one of police officers, one of the IS, but it didn’t erupt into anything more than that.’

He said that being in IS was great cover for spying on other groups, as everyone expected IS newspaper sellers to turn up at every event and let them be. However, he seems to have done very little reporting on organisations beyond those he was actively infiltrating.

Challenging his deployment due to its pointlessness wasn’t something that even occurred to him:

‘I wouldn’t have thought of doing that [challenging it] anyway because I was happy to go in areas that they were short of officers in.’

Asked if he remembered any demonstrations against the fascist National Front turning violent, Harris drew a blank.

DEATH IN RED LION SQUARE

Nevertheless, early in his deployment, on 15 June 1974, Harris attended a counter-demonstration against the National Front at Red Lion Square, London.

Police charged the crowd, with officers on horses using batons to strike protesters’ heads. Following one such charge, protester Kevin Gately was left unconscious from a blow to the head, from which he later died.

It was the first time anyone had been killed at a demonstration in Great Britain for decades. As with all the other spycops who have been asked, Harris claimed not to remember the event, let alone any discussion among his colleagues. He vaguely admitted to remembering Gately’s name ‘now you mention it’.

There were surely many reports written about this demonstration, but the Inquiry has been unable to find very much at all.

PART OF THE GROUP

Harris was part of the Twickenham branch of IS. Meetings averaged about 15 people, sometimes as many as 25, though these were not all members as most meetings were open – undermining his earlier talk of needing to be deep undercover to access these meetings.

He was appointed as the branch’s Contact Secretary. He says this meant he had a notebook full of members’ contact details:

‘obviously, every time there was a new contact it would come through me, so that could be useful, depending on who they were’

However, Harris denies having too much influence over the direction of the group. He claims to remember being told early in his deployment that his role was reactive, rather than pro-active, and that he shouldn’t lead the action in any way, nor take up senior official roles that could steer a group’s direction. He was not questioned further on the obvious disconnect: if he was the first point of contact for new members, and the public face of the group, he had a great deal of influence.

He did not deny voting at meetings, but said he just voted with the majority, so his vote didn’t really matter.

But what would you do if it did matter?

‘It depends’

The Inquiry did not pursue the point. This fact highlighted the problem of the Inquiry asking questions supplied by lawyers as a check-list exercise, without knowing what point they’re trying to elicit nor how to press an issue. See the comments at the end of the report for more on this.

Harris recorded trade union membership in reports. A January 1975 report [UCPI0000012060] of a meeting of the West Middlesex District of the IS refers to two recent strikes. However, Harris says this is the only time he remembers any discussion about IS getting involved with industrial action.

SCHISM AND THE WORKERS LEAGUE

The Twickenham branch of IS had a schism with the national leadership, which led to the branch being suspended and becoming a branch of the Workers League (WL).

The WL was a small organisation having a total national membership of only 143. As to whether they were subversive, Harris mused:

‘Not particularly, no’

Were they a threat to public order in any way, then?

‘It was never discussed at the early meetings, the ones which I went to’

He kept spying on them anyway.

Harris recorded which IS branch each Workers League member had belonged to, as well as details of their trade union membership. He also reported details of theiremployment – for example, a December 1976 report [UCPI0000017609] notes that a member works for the London Borough of Ealing.

Asked why this was worth reporting, Harris explained:

‘if they were employed in a position like that in a council, or also if they were employed in a college or something like that, it would be normal to put it in’

Harris wasn’t asked why these institutions were ones that would be ‘normal’ to report on, let alone if it was believed to contribute to public sector blacklisting. It’s already established that every constabulary’s Special Branch routinely supplied a construction industry blacklist with personal details of politically active people. It seems unlikely that was the only sector.

SAFE HOUSE MEETINGS

Harris went to SDS meetings at the unit’s safe houses twice a week, once at each of two locations. The majority of the active spycops attended these, unless there was a specific reason they couldn’t.

Reports were submitted on Mondays, with the spycops aggregating and formalising notes from that weekend’s demonstrations.

Sometimes there would be some group discussion, which he described as relaxed and open:

‘They were normally fairly light hearted… It was just basically an open forum that people could throw anything in, and obviously some of that affected other people and they might have experienced something similar’

He would spend around four hours at the safe house with his fellow spycops on Mondays.

He estimated that the meetings on Thursdays went on for longer – maybe six hours – as these were more social occasions. Sometimes they cooked lunch, and they would talk about problems and share experiences:

‘It was time to get away from all the undercover stuff and get, you know, back to normal a bit’

Harris recalled two occasions when the highest officer in the Met, the Commissioner, visited the SDS at their safe house. Harris remembers Robert Mark and, later, his successor, David McNee, both visiting during his deployment.

This tallies with similar reports by spycops from the 1960s and 1990s. This suggests it was an established part of the Commissioner’s role, or at least the existence of the unit was something brought to the attention of every Commissioner.

Harris said that, at some safe-house meetings, they were asked for suggestions about ways to infiltrate more extreme groups or events.

All this seems plausible for a group who would meet hundreds of times with the only other people who could possibly understand their lives. And yet, it is in direct contradiction to the tight-lipped responses from the majority of other undercover officers who have given evidence.

Just 24 hours earlier the Inquiry was being told by Harris’ contemporary ‘Mike Scott’ (HN298, 1971-1976) that spycops at the meetings didn’t discuss politics or anything else that affected their work, not even if they were likely to be at the same upcoming event.

SEXUAL RELATIONSHIPS

Harris was friends with the late Richard Clark (‘Rick Gibson’ HN297, 1974-76). The pair had known each other before the SDS, and would do so long after as well. Clark deceived four women into relationships while undercover.

Harris claims they never really discussed details of their undercover work. He knew that Clark had infiltrated the IS, but says he only learnt today that he also reported on the Troops Out Movement.

The Inquiry asked Harris if he recalled Richard Clark having a reputation of being a ‘ladies man’, as has been alleged by another officer, or whether he remembers Clark being teased about this reputation within the unit?

Asked if he remembered ‘Jim Pickford‘ (HN300, 1974-76) having a similar reputation, he replied:

‘I think the answer to that would be yes’

They inquiry did not follow up on this straight away, but after the a break to allow core participant lawyers to make representations, Counsel returned and did press the point.

He seemed at pains to say he knew this without admitting it was ever discussed among spycops. Instead, he said he was aware of the reputation because:

‘I was in hospital and he came to visit me, and I didn’t see him for the visit. But when he went, my nurse came and said “oh your friend’s very nice,” and he’d been talking to her all the time instead of visiting me.’

Full witness statement of ‘Roger Harris’

FORMAT FAILING THE PURPOSE

The questioning of Harris by one of the Inquiry’s Counsel, in this case Rebekah Hummerstone, threw into stark relief an issue that has dogged the Inquiry throughout these hearings and also the previous ones in November 2020.

Whilst the Inquiry’s use of a ‘neutral’ Counsel to ask the questions steers it away from having an ‘adversarial’ format, it also leaves key questions unanswered, and points set out but not responded to properly – because this Counsel has simply moved on to the next thing on their list rather than unpacked an answer or pressed a point that the witness is avoiding.

This is particularly true where the question comes from the ‘non-State core participant’ victims of spycops. Too often merely asking a question is deemed sufficient. This is problematic when it is asked in a different way from what has been submitted.

Another problem is that those asking the questions don’t always take the time to understand the reasoning behind asking the question in the first place. This means that they often do not see the relevance of the answer or know how to deal with it. This causes some hair tearing, when having elicited a significant response, there is no follow-up and the moment is squandered.

This not only undermines the point of asking the question, it defies the purpose of having a witness appear in person at all.

<<Previous UCPI Daily Report (4 May 2021)<<

>>Next UCPI Daily Report (6 May 2021)>>