UCPI Daily Report, 12 May 2021

Tranche 1, Phase 2, Day 15

12 May 2021

Summary of evidence:

‘Colin Clark’ (HN80, 1977-82)

‘Barry Tompkins’ (HN106, 1979-83)

Introduction of associated documents:

‘Bill Biggs’ (HN356/124, 1977-82)

Evidence from witness:

‘Paul Gray’ (HN126, 1977-82)

The Undercover Policing Inquiry hearing of 12 May 2021 gave summaries of three officers from the latter part of the period currently under examination (1973-82), before spending most of the day questioning officer ‘Paul Gray’ who infiltrated the Socialist Workers Party and the Anti-Nazi League.

![We Did Not Consent: Police Spies Out of Lives banner at Beechcroft Avenue, where police killed Blair Peach in 1979 [Pic: Police Spies Out of Lives]](http://campaignopposingpolicesurveillance.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/beechcroft-ave-680x454.jpeg)

We Did Not Consent: Police Spies Out of Lives banner at Beachcroft Avenue, Southall, where police killed Blair Peach in 1979 [Pic: Police Spies Out of Lives]

Summary of evidence:

‘Colin Clark’

(HN80, 1977-82)

Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) officer ‘Colin Clark’ (HN80, 1977-82) infiltrated the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) and was also active in the ‘Right to Work’ marches.

He is still alive and, despite the Inquiry’s Chair Sir John Mitting having previously said Clark’s deployment was ‘of significance’, he is not being called to give live evidence in the Inquiry. He has provided a written witness statement.

Before joining the SDS, he worked in other parts of Special Branch, including its ‘C’ and ‘B’ Squads. He says several times that the spycops unit’s existence was secret, even within the Branch. However, he socially knew another undercover, Richard Clark (‘Rick Gibson’ HN297, 1974-76), who persuaded him to volunteer for the SDS.

He knew – from talking to Rick – that the work would be ‘demanding and required high standards of intelligence and initiative’.

He did not realise how much time he would be required to spend away from his wife and young child – something that varied over time.

He recalls Detective Inspector (DI) Geoff Craft telling him that for security reasons his cover name would be classified as secret, and never released into the public domain. He says he had lengthy conversations with Craft, and that his task was to:

‘gather the best information on extreme left-wing activists and groups that I could be involved with’

in order:

‘to protect the public in London, assist the MPS [Metropolitan Police Service] to deal with demonstrations and the Security Service in its counter-subversion role. Those three objectives did not change during my deployment, although dealing with terrorism and terrorist supporters came into clearer focus as part of protecting the public.’

TRAINING & GUIDANCE

Clark started working in the SDS office in December 1976, and was then deployed into the field undercover in March 1977. He says he learnt a lot from seeing the documents that came in, but:

‘It was much more a process of familiarisation, both as to the types of information that were useful and how this might be obtained, as well as to the general issues concerning the left-wing.’

His training consisted only of a series of discussions with SDS managers. There was no formal guidance on how much he should become involved in the private lives of the individuals he spied on. He says there was no need for advice on intimate relationships – he was adamant he would never engage in such relationships, because of his ‘strong family values’, saying:

‘I prepared my back story to forestall any advances.’

Likewise, with being arrested:

‘The nature of the unit was such that we were not expected to go to court as police witnesses… no advice was given about attending as a witness in any other respect’.

He was not given advice on becoming privy to legally privileged information or the ethical implications which would apply to him as a police officer in this eventuality.

COVER IDENTITY

Clark’s cover name was chosen following long discussion with Mike Ferguson (HN135, a former undercover who became an SDS manager). It was agreed a nickname would be useful, so he chose ‘CC’ and says he extended this out into ‘Colin Clark’.

Unlike other officers from this period, he refused to steal an identity stolen from a dead child, as the idea of it distressed him, as did the idea of the family finding out. In order to ‘show willing’, he says he located a death certificate, from a ‘Paul Clark’. He insisted on using the cover name ‘Colin Clark’, and giving ‘Colin’ the same birth-date as his own real one. His managers went along with this.

Clark grew his hair and beard. Once he began living in his fake identity he dressed down. He invented a serious, long-term, long-distance relationship with an airline hostess in New Zealand. This gave him an excuse to reject advances, but also facilitated his exit strategy, while protecting his cover identity once he left the field:

‘people would be more willing to believe I was someone else if the Colin Clark they knew had emigrated.’

He said of his wider relationships with people in the groups he targeted:

‘I maintained a friendly distance as much as possible from all of the individuals with whom I had contact during my deployment. While it was not always an easy or comfortable balance to strike, I believe I would have been considered as an “able comrade” or as a friend. I was never anything more than this.’

EMPLOYMENT, ACCOMMODATION & VEHICLE

He initially had short-term cover employment, but that became problematic so he ‘went freelance doing vehicle repairs’.

Clark arranged a bedsit for himself in Muswell Hill. He chose the area as his managers said it would be a good location for making contact with leading left-wingers. Whenever ‘Colin Clark’ went away, he arranged accommodation for himself and avoided sharing with other campaigners.

He had a Morris 1100, and later a Ford Cortina, both provided by the police.

DEPLOYMENT

Clark says he was directed to focus his attentions on ‘the Left’ in Haringey, not any specific groups. He says that there were conversations with his pre-deployment managers – Craft, Ferguson, and Sean Lynch (HN68, 1968-74) – and he was told to use his initiative in order to:

‘find an effective way to get information on extreme left-wing and revolutionary activity.’

He took his time before targeting any groups, ending up gravitating towards the Socialist Workers Party (SWP), and establishing himself slowly.

He had significant discretion in how he operated:

‘the key aspect of this was that I had to act consistently with my cover identity and legend and not compromise my real role as a UCO [undercover officer].’

REPORTING

He naturally attended the events of groups associated with the SWP: the Anti-Nazi League (ANL) and Women’s Voice (WV). He says he had limited contact with the latter due to their radical feminism, but once gave a lecture to a WV group.

Clark says he also came into contact with Troops Out Movement, Labour Party members, assorted trade unionists and others on the left, and ‘Provisional IRA terrorist supporters in North London and the Kilburn area’.

He notes the absence of reports from the second half of his deployment when:

‘I know I was gathering information about links between the extreme left-wing in Britain and Irish terrorist organisations.’

The reports provided to him by the Inquiry do not reflect his memories of what he reported on (often by telephone). He notes that there are no reports at all from the period spanning November 1978 to July 1979.

Clark also reported on industrial disputes:

‘Industrial disputes have an intrinsic risk of public disorder, and so early reporting of these could be of assistance. As far as I was aware, there was no standing instruction to report industrial disputes unless there was potential for violence or disorder.’

He says that simply being able to list those who attended a meeting – not even the details of what was said – was considered ample justification for spying on it. He denies authorship of some of the reports attributed to him.

There is an SDS report from 1982 [UCPI0000017230], which includes a list of contacts (including details for Peter Hain and Celia Stubbs, two of the non-State core participants involved in this Inquiry) from somebody’s personal address book.

Clark says:

‘I never obtained or sought to use anybody’s personal documents for information purposes, such as the address book here. I was more than content, however, to report details contained within any organisational documents that I was given.’

SOCIALIST WORKERS PARTY

He struck up conversation with SWP newspaper sellers and was invited to go to a meeting around May 1977. By that summer he had joined his local branch, Seven Sisters & Haringey, and was going to their meetings, paying subs, and generally making himself useful.

He started out selling the Socialist Worker newspaper, steadily becoming more involved at branch level, and then in the organisation’s work more widely. As many of his spycop colleagues, he took the role of treasurer in the organisation he was infiltrating, presumably because it would allow him access to membership details.

He says that he gave talks and yet somehow didn’t try to persuade anyone about any political ideas.

‘I did not push myself forward but I allowed other members to suggest that I take up the branch treasurer role. From there, I went on to be the treasurer for the Lea Valley district organisation… and this meant that I was then required to attend meetings of other branches within the district.

‘The SWP was highly organised and bureaucratic with frequent meetings, and a great deal of cross-over and support to other groups. As my deployment continued, I became involved in lecturing at their request… and also assisted other SWP groups within the region with running their affairs but only ever on a practical level. I never sought to direct their policy or activities.’

One example of this assistance was the help he gave to the Tottenham branch of the party after it ran into problems. He was involved in reforming it, and ended up chairing some of its business meetings on a temporary basis.

Clark reflected on his responsibility in terms of the democracy of those meetings:

‘All this would have entailed was having a vote at district meetings, and I tried to ensure that my vote always followed the majority, and that I never advocated anything which was contrary to good order.

‘As I have described above, my managers trusted me to act appropriately, so I do not believe I was even required to inform them of these developments, although they may have been discussed at some point.’

Having been encouraged to join in with the SWP’s sporting activities, he developed a friendship with leading party activist John Deason, so was able to report on him and his activities too.

INFILTRATING SWP HEADQUARTERS

Clark says that at one point he was asked to join the SWP’s Central Committee, but turned this down with the excuse that he was too busy. He was able to provide high-end intelligence to his managers as he had access to the SWP’s headquarters and a lot of information.

He explains that:

‘as a vehicle mechanic, I helped colleagues out if they had problems with their cars.’

This was extended to activists who who worked at the headquarters that he got to know, and led to him being asked to help the party out with administrative work:

‘because I was self-employed, I agreed. This was not something that I sought out actively but it very conveniently granted me access to the kinds of information that even a district treasurer would struggle to obtain. It was also a good opportunity to understand the dynamics of the organisation.’

This meant that he spent lots of time inside their main office building, around their secretariat.

He says:

‘My access to the SWP headquarters was ad hoc when I was asked to help out. I did not have a totally free run of the building but I was there with varying frequency from 1978 onwards, starting with the preparation for the national delegate conference that year. My managers would have been aware of my involvement at the headquarters from my reports.’

The documents he had access to included the SWP’s weekly internal bulletin, which contained a lot of details of the party’s paper sales, priorities and plans.

Clark was deployed until March 1982. He was not directly succeeded by another undercover, but is aware his deployment was extended to allow ‘Phil Cooper’ (HN155, 1979-83) to establish himself in the field.

He travelled outside of London for events, such as attending the SWP conference in Birmingham and giving a lecture in Liverpool.

He attended the SWP National Delegates Conferences between 1978 and 1981, and worked as a steward or administrator:

‘because of the ad hoc work I was doing around headquarters and because they already relied on me as a helpful and organised “comrade”.’

He received a Deputy Assistant Commissioner’s commendation for his report on the 1979 conference.

RIGHT TO WORK CAMPAIGN

Clark allowed himself to be put forward to help with the admin of the Cardiff-to-Brighton Right to Work (RTW) march:

‘My analysis was that I could just as easily provide relevant information if I was helping with the catering, driving and dealing with donations received en route.

‘I was not tasked to get involved in RTW by my managers. They would only have known about RTW once I became involved. I would have kept them updated once I was invited to assist.

‘My position as National Treasurer enabled me to have access to good quality information without getting involved in policy or organising events, which I felt was consistent with my role as a deployed UCO.

‘I attended the entirety of the 1980 RTW march and drove one of the support vehicles as well as cooking on the evenings that no other arrangements were possible.’

He received another official commendation his contribution to a comprehensive report on the RTW march in 1980 [UCPI0000014610]. Clark’s successor of sorts, ‘Phil Cooper’, also a drove a support vehicle on the 1980 RTW march.

Clark’s witness statement describes the RTW demonstrators being attacked, with Clark himself having to fight off his assailants:

‘I was successful at providing information to my managers before the event and along the route of the march, including detail that large numbers were planning to attend the final picket of the Conservative Party conference in Brighton at the conclusion of the RTW march. This picket turned violent and it was the one occasion that I was not able to stay on the sidelines.

‘As I recall it, the disorder started around me, during the course of which I was badly assaulted around the head and shoulders, receiving severe bruising. It was also the only occasion when I struck out, although only in self-defence.’

This quote is fascinating for the way it fails to attribute the violence. Disorder ‘started around me’ and ‘I was badly assaulted’, but by whom? It won’t have been his comrades, as they would be on his side (and he would surely have specified, SDS officers seem to love the chance to report disorder committed by their target groups). Conservative conference delegates seem a very unlikely option. It would appear that he must be talking about his uniformed colleagues.

Assuming this is the case, it is yet another instance of a spycop being assaulted by police while undercover.

ANTI-NAZI LEAGUE

Clark’s targeting of the Anti-Nazi League was done on his own analysis and initiative. There were many violent clashes between the ANL and fascists in East London. He says:

‘the key thing was to get information to the local police in a very timely fashion given the relatively poor communications compared with today’s.’

He says he avoided getting too involved with his local (Haringey and Enfield) ANL group, or organising anything, but would sometimes attend their events.

Following a question about the reporting of the 1978 ANL Carnival [UCPI0000021653] he states:

‘In my view, it was justifiable and proportionate to report on this organisation, on the basis that the ANL was known to use violence and seek out confrontation. It was important to know where its support came from and was likely to come from in future.’

As ANL organiser Peter Hain said in his statement, the ANL’s strategy was one of non-violence.

SDS FIELD OFFICE

As well as their back-office at New Scotland Yard, the SDS had two field offices, or safe-houses, in West and South London. The spycops attended meetings at these flats twice a week. This is when they submitted their reports, and expense claims.

Right to Work march outside the Conservative Party conference, Brighton, October 1980

Sometimes they would put together a report about an event, or look at photographs to identify people in them, or ‘de-conflict which officers would attend the bigger events’. These get-togethers also provided opportunities to bring up personal issues with the SDS managers.

Clark says he didn’t enjoy these gatherings, and reduced his attendance to once a week, with his managers’ agreement, as his undercover life got busier. He was concerned that the meetings represented a security risk, and a threat to his cover identity. He only occasionally met up socially with the other spycops, and says that when they did this, they never discussed the details of their deployments.

Clark would call the SDS office every weekday. If there was any emergency, he says he could reach managers at their homes.

OVERTIME

His pay increased significantly because of the huge amount of overtime he did – estimating that this would have added up to many thousands of hours over his five years in the unit. The spycops could be paid for any time they spent maintaining their cover as well as the time they actually spent with target groups. He recalls that there was some kind of upper ceiling on how many hours they could claim for.

A CLOSE CALL

On 7 June 1980 Clark was off-duty, shopping with his wife and child, when he was spotted by some SWP paper sellers. They recognised him, having seen him lecture, and came over to the family. Two of them took his wife aside and one of them:

‘found out my real surname and our home address. It was she who noticed my wife’s engagement and wedding rings on her left hand and told her “you must be married”. My wife confirmed this at the time.’

Worried that this woman would carry out her threat to visit them at home, he says he spent about three months living at his cover accommodation until they managed to move house. He says he sought permission from the Met to live outside the usual 20-mile limit, and was supported by his SDS managers in this, but his application was turned down.

EXIT

‘My exfiltration was planned with my managers but I was responsible for its execution. As mentioned… above, my back story included a long-term, long-distance relationship and I just let it be known that I was going out to New Zealand to spend more time with my partner and start a new life.’

The SWP held a leaving party for him, and John Deason drove him to the airport, having helped him dispose of his minimal possessions.

Clark was one of many spycops who have used a move to another country as part of their exit story.

Written witness statement of ‘Colin Clark’

Summary of evidence:

‘Barry Tompkins’

(HN106, 1979-83)

Until the 2021 hearings started, the Inquiry had said that ‘Barry Tompkins’ (HN106, 1979-83) had infiltrated one main group – the Spartacist League of Britain (SLB) between 1979 and 1983.

While Tompkins did spend time with the SLB it seems groups such as the Revolutionary Communist Tendency, Revolutionary Marxist Tendency, and Workers Against Racism were as much, if not more, of a focus for him.

We are told that his health is deteriorating, and this is why he is not giving live evidence to the Inquiry. However, he did provide a witness statement.

JOINING THE MET – AND THE SDS

Tompkins joined the police in the early 1970s. He did plain clothes work in Special Branch for six months before joining the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS). His recollection is that he was told there were vacancies within the SDS and so approached Mike Ferguson, then head of the unit.

Tompkins was asked if he was married, which he was. The SDS preferred to use married officers for this undercover work, thinking they were less likely to ‘go rogue’.

IDENTITY THEFT & BACK STORY

In order to construct his cover identity, he stole the name and date of birth of a deceased child, Lionel Barry Tompkins. Cover employment was as a delivery driver for a garden centre in Greater London. He also had a cover vehicle, which he occasionally used to transport activists.

Tompkins used several cover flats during his time undercover. Towards the end of his deployment he shared his Stoke Newington place with another undercover, Michael James (HN96, 1978-83) – who is giving evidence to the Inquiry on the 13 May.

INFILTRATE ANY GROUP (AS LONG AS IT’S LEFT-WING)

Like other undercovers, Tompkins was allowed considerable latitude about who he targeted.

He was not directed to infiltrate any group in particular, but told to focus on the ‘far left’, albeit with the proviso that major left-wing groups, such as the Socialist Workers’ Party, were already well covered by spycops.

FIRST REPORT: SPYING ON THE BLAIR PEACH CAMPAIGN

Deployed into the field in April 1979, the earliest report identified as being authored by Tompkins is dated 30 May 1979 [UCPI0000021297]. It includes a double-sided leaflet from the Friends of Blair Peach Committee, set up after Peach was killed by police at an anti-fascist demonstration. There are other intelligence reports linked to officer ‘HN109‘ on the subject of this justice campaign.

A report from May 1980 [UCPI0000013961] lists the names of people who attended a Friends of Blair Peach demo.

Another report [UCPI0000014149] mentions a new initiative; Peach’s partner Celia Stubbs and other members Friends of Blair Peach wanted to create a national network of groups campaigning about State brutality (such as the campaigns around Richard ‘Cartoon’ Campbell and Jimmy Kelly).

A July 1979 report [UCPI0000021047] lists some of the attendees at Peach’s – it is signed by SDS chief Mike Ferguson. Last week Celia Stubbs told the Inquiry how angry she felt about Special Branch monitoring her late partner’s funeral. Tompkins says that this was not his reporting, and it does seem likely that this list was compiled from information gathered from more than one spycop.

I‘M SPARTACUS!

Tompkins states that he came across the Spartacist League of Britain (SLB), which he describes as a revolutionary Trotskyist group, because they were active in the part of East London where he’d chosen to base himself.

Tompkins recalls speaking with some SLB members and thinking that they might be of interest to the SDS as they expressed pride at having thrown bricks at police officers during the Miners’ Strike pickets (which would have been seven years previously, in 1972).

He says the Spartacist League did not pose any significant challenge to public order. They were more intellectual than they were active. The Inquiry highlights some of the rhetoric of their weekly newspapers, but Tompkins thinks the only threat posed by the group was a theoretical one.

However, he believes their support for the Provisional IRA may have been of greater concern and thought:

‘The Spartacist League would have been capable of providing low-level support to the Provisional IRA.’

He did not provide further details as to what that might mean.

BUILDING UP CREDIBILITY

Tompkins thinks that he began buying the SLB newspaper and then began attending their meetings. He described his preparations, going to some general left-wing and Labour Party events and making sure to get a good grounding in Marxist/Trotskyist literature.

He feels the SLB were initially cautious, but gradually accepted him. Tompkins says he would not have been considered a member but instead as a relatively trusted supporter. The SLB is the main subject of intelligence reports attributed to him until mid-1980.

Actual offences committed are thin on the ground. Tompkins says that this did not go beyond low-level criminality such as spraying graffiti on Bow Bridge in London – where he acted as look-out so avoided active participation.

REVOLUTIONARY LABOUR LEAGUE

Tompkins’ reports from summer 1980 include some – [UCPI0000014134 & UCPI0000014148] – about the Revolutionary Labour League (RLL), a tiny group, whose members sometimes also attended Spartacist League meetings.

REVOLUTIONARY MARXIST TENDENCY

The Revolutionary Marxist Tendency (RMT) was ‘effectively a sister organisation’ to the SLB, and mentioned in some of Tompkins’ reports. It was allegedly formed by a merger between the RLL and some people who had left the Revolutionary Communist Tendency (RCT) in mid-1980. There is also mention of a ‘Leninist Tendency’ and lots of overlap between all of these groupings.

TOMPKINS’ OWN THREE-PERSON FACTION

Tompkins describes his own involvement in a brand-new activist group. He says that he – along with two disaffected individuals who he’d met through the SLB and/or RMT – started their own splinter group (whose name is unknown). He says these two people are the ones that he got closest to, and they would socialise together two or three times a week.

It is hard to imagine what the interest of Special Branch could be in a group consisting of three people – including Tompkins himself. Although this speaks to the sheer absurdity of SDS activity, it should not obscure just how out of control the unit was.

REVOLUTIONARY COMMUNIST TENDENCY

The majority of Tompkins’ reporting from 1980 onwards concerned the Revolutionary Communist Tendency (RCT) and Workers Against Racism (which was connected to it). The RCT changed its name in 1981, and was then known as the Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP) until 1996.

BARRY TOMPKINS & THE SOVIET ATTACHÉ

Given that the deployments that have been examined between 1973 and 1982 occurred at the height of the Cold War, there has been surprisingly little talk of connections between the infiltrated groups and ‘hostile’ foreign powers.

Tompkins’ deployment contains one, or possibly two, exceptions to this. He describes what he believes to have been an attempt by a Soviet embassy attaché to recruit him as a courier. He says he was told at a meeting in a Hackney pub that he would have to go to Russia for training. He told them that he needed time to think, and consulted his managers. However, they didn’t allow him to go, fearing that his cover identity wouldn’t stand up to the possible scrutiny.

Tompkins states that he had no further contact after telling this alleged KGB officer that he wasn’t seriously interested. He says that he saw a story in a newspaper later, suggesting that this officer was expelled for trying to recruit sailors in Plymouth.

His intelligence reports record this Russian as attending two RCP meetings in 1982 [UCPI0000018248]. The Inquiry has obtained contemporaneous documents from the Security Service (MI5) which largely corroborate his account [UCPI0000028784, UCPI0000028795].

Tompkins believes that he came into contact with another foreign security service. He says that he and his faction-of-three were in contact with an individual who was very keen to hear about any anti-apartheid activity, and paid them ‘money estimated to be in the hundreds in total’ in exchange for ‘little bits of information’.

This is not recorded in any of the intelligence reports and we are left to imagine what these little bits of information might have been.

WORKERS AGAINST RACISM & BLACK JUSTICE CAMPAIGNS

Many of the spycops focused on anti-racist campaigning – including that of Black family-led justice campaigns. Back in 2018, we compiled a list of these campaigns.

Workers Against Racism (WAR) was set up by the SBL/RCT/RCP, and attracted more supporters as you didn’t have to be a communist to join WAR, just against racism.

Through spying on East London Workers Against Racism (ELWAR), Tompkins came into contact with victims of racist violence and specific justice campaigns. One of his reports records a visit by a delegation of 17 ELWAR members to a housing estate in Walthamstow to garner ‘physical support’ from residents for a family who was being racially harassed [UCPI0000018095].

Tompkins justifies this reporting, with the amazing reasoning:

‘If I came into possession of information that people were being attacked and racially abused, I would have thought this should be passed on to the police.’

Tompkins was involved with ELWAR’s campaigning during the Greater London Council elections of May 1981. He recalls being tasked by his managers with assessing the accuracy of a Daily Mail article that year which suggested that ELWAR was a militant organisation.

Tompkins reported on an ELWAR meeting in April 1983 [UCPI0000019008] and included details of the group’s involvement in the case of a 13-year-old boy who had been beaten up and stabbed by police officers in Notting Hill, whose case had been turned down by a law firm. He was asked whether this incident would have the same ‘agitative effect’ as the case of Colin Roach, whose killing in a police station had led to a campaign for a public inquiry.

Tompkins also reported on the Hackney Legal Defence Committee and Newham 8 Defence Campaign [UCPI0000015892]. This report also names noted lawyer Gareth Peirce. His other reporting on justice campaigns included the New New Cross Massacre Action Committee [UCPI0000017186], and the Winston Rose Action Campaign [UCPI0000015540].

A November 1981 report [UCPI0000016706] summarises the contents of a WAR document entitled ‘Racist Violence and Police Harassment’, referring to a number of families in the Brixton area who have suffered ‘brutal treatment at the hands of police’ and of ‘racist attacks where the police have taken no action or obtained no result’.

Tompkins states that such campaigns were not a particular focus of the SDS – although the evidence suggests otherwise.

SENSITIVE INFORMATION

Tompkins said he reported all of the information available to him, and his reports bear this out. They include personal information about individuals, including addresses, telephone numbers, occupations, employer details and car descriptions together with registration numbers. The reports also contain more specific personal information, such as details of the subject’s partner and family, information about who group members live with, etc. One example is this report from September 1979 [UCPI0000013345].

REPORTING ON SEXUAL ACTIVITY & EVERYTHING ELSE

Even more intrusive is a report of September 1980 [UCPI0000014258]. It not only records that the subject of the report was ‘presently indulging in a sexual relationship’ but also contains the comment that:

‘Judging by the depressing regularity with which [redacted] suffers from attacks of cystitis, neither is permitting [redacted]’s tenuous position in the United Kingdom to interfere with more immediate needs.’

Another report from the same month [UCPI0000014543] details how an RMT member had been suspended by them for misappropriating party funds, and the theft was to pay off a sex worker. It also superfluously and cruelly adds that the person had a ‘physical deformity’.

Equally troubling is an April 1983 report [UCPI0000018782] which records that someone:

‘Recently had an abortion at a South London ‘day abortion’ clinic. Whilst the identity of the putative father is not certain it is known that [redacted] previously had a relationship with [redacted].’

In his written statement, Tompkins doubts that he authored many of these reports and/or included many of the personal details cited above.

SEXUAL RELATIONSHIPS – NONE, ONE OR TWO?

Tompkins was interviewed by Operation Herne (the internal police investigation into the spycops scandal circa 2014) regarding a possible relationship with an activist.

Tompkins understands this was due to a Security Service document [UCPI0000027446] of July 1982. It says that Tompkins has been ‘warned off’ a [redacted group], as he has ‘probably bedded’ a woman – who presumably had a connection to the anonymised group.

Tompkins denies this accusation – and says he has no clear memory of who this person is – yet states that the only reason he remembers her is because she had a ‘party trick’ of lactating on demand and demonstrated this to activists on a couple of occasions.

However, Tompkins does concede that he developed a very close relationship with a different woman – an ex-partner of an activist whom he’d been spying on. Tompkins says he ‘bumped into’ her a few months after she had split up with this partner. He says a purely platonic friendship developed, and they would meet up for drinks, he would stay over at her house (but according to him, he would sleep in one of the children’s rooms and the children would share with her).

As a result, some activists began to refer to her as ‘Barry’s girlfriend’. Tompkins states that he did not correct them as it was helpful for his cover for people to think he had a girlfriend.

Trevor Butler, a manager in the SDS, asked to speak to him about an intercepted (bugged) telephone call that had mentioned ‘potentially storing items from Ireland at Barry’s girlfriend’s place’. Tompkins thinks Trevor Butler said something to him along the lines of:

‘You’re not going to get us into trouble are you?’

To which he replied:

‘No, it’s nothing like that.’

Tompkins wrote that he was ‘sad when he had to disappear’ from this woman’s life. What he does not explain is why he formed such a close relationship in his cover identity with someone who was not an activist – and by his own account was not a target of surveillance.

TOMPKINS INTELLIGENCE USED FOR DEPORTATION?

Tompkins describes how, about five years after he left the SDS, he was contacted by Tony Waite, who he believes was the Inspector in charge of the SDS at the time. He asked Tompkins about the accuracy of his reporting concerning a particular individual, which he confirmed. This was in connection with a possible deportation.

DEBRIEF

Unlike some of the earlier spycops we’ve heard from, Tompkins says he was fully debriefed following his deployment. There is a document [UCPI0000034280] from October 1983, which appears to have been created by MI5 to collate his intelligence about the RCP.

Tompkins has told the Inquiry that he never joined any trade unions whilst undercover, but this report says he joined the TGWU, at the behest of the RCP (who wanted him to go on to get involved in Trades Councils), and was a member for a while, until he allowed this to lapse.

The report offers an interesting insight into the party’s structure, rules, discipline and the standards/ level of commitment expected from members. It refers to the:

‘grindingly boring nature of average RCP activity.’

PRIVATE INVESTIGATOR

One issue which the Core Participants wanted the Inquiry to explore was whether undercovers took their knowledge and skills to the private sector after leaving the police. The Inquiry is only asking one very narrow question about this – specifically asking if they did any more undercover work after retiring from the police – rather than a broader question about them using their inside knowledge, ‘tradecraft’ or other expertise.

Tompkins says that for a period in the 1990s, he worked as a private investigator. He describes one occasion when he was asked to carry out a check for a company that was considering investing in a business proposition. To do so he pretended to be a potential investor, using a fake name.

Note: The Inquiry was intending to request a supplementary statement from Tompkins, to address new documents that have come out and other matters in his written statement, but has not done so due to his deteriorating health.

The Inquiry also states that photographs of Tompkins have been shown ‘privately’ to ‘civilian witnesses’. We do not know which civilian witnesses they have been shown to as no former members of the groups that Tompkins infiltrated have been granter Core Participant status at the Inquiry. One former member of SLB applied for such status and was refused.

Written witness statement of ‘Barry Tompkins’

Introduction of associated documents:

‘Bill Biggs’

(HN356/124, 1977-82)

‘Bill Biggs‘ (HN356/124, 1977-82) infiltrated the Socialist Workers Party in South East London and subsequently Brixton, from February 1978 to February 1981. He also reported on the Anti-Nazi League, the Right to Work Campaign, and the Greenwich and Bexley branches of the Campaign Against Racism and Fascism.

It’s likely that he additionally reported on the Brixton Defence Campaign, set up to support those arrested in the 1981 Brixton Riots. He is notable for the extent to which he reported on anti-racism work.

He is deceased. The Inquiry produced a summary of material and released documents relating to him.

DEPLOYMENT

Biggs joined the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) in October 1977 and was married throughout his deployment.

He replaced Roger Harris (HN200, 1974-1977) and another unnamed undercover being deployed in SWP. This other officer is presumably one of the spycops for whom the Inquiry has chosen to restrict all details.

SOCIALIST WORKERS PARTY

Biggs is one of many undercovers who targeted the SWP in London. He focused on the south east branches of Plumstead and Greenwich initially.

Like a number of his contemporaries in the SDS, such as Vince Miller (HN354, 1976-79), Biggs was active around the ‘Battle of Lewisham’ anti-fascist demonstration on 13 August 1977. However, this appears to be before he joined the SDS, so probably must have been present as a standard Special Branch plain clothes officer. If so, he is one of the eighteen Special Branch officers cited as being on duty that day.

One report [MPS-0733365] notes that Biggs telephoned Special Branch to say that at 14.55 on the day SWP ‘heavies’ would go to Church Street in Deptford, ready to attack the National Front marchers. This information was passed straight to the public order branch’s operations room.

It is around five months after Lewisham that we find the first report [UCPI0000011713] attributed to him as an SDS undercover. It is for a meeting of 24 January 1978 of the SWP’s South East District.

After this, Biggs regularly reported on the Plumstead branch meetings. Membership stood at seven people in March 1979, and attendance was often between five and ten people. In December 1978, Biggs chaired at least one meeting, his name given as ‘William Biggs’ [UCPI0000013021].

The Inquiry notes the tone of some of this reporting is dismissive, giving an extract from a February 1978 report as an example [UCPI0000011814]:

‘After a meaningless tirade on the exploitation of women, “gays” etc. and a brief discussion, the meeting was finally brought to a close.’

TREASURER & PAPER SALES ORGANISER

Biggs quickly rose to prominence in the organisations he infiltrated. He was elected treasurer of Plumstead branch of the SWP by April 1978 [UCPI0000011996] and in December 1978 became Branch Organiser for the Socialist Worker newspaper [UCPI0000013021] subsequently resigning as treasurer [UCPI0000013029].

In taking these positions, Biggs mirrors many of the other undercovers in the SWP from the era. Treasurer and membership secretary seem to have been common positions for spycops, presumably as they give access to the personal details of all members.

In September 1979, Plumstead merged with Greenwich branch [UCPI0000013398] but this was short-lived. Plumstead reformed in November 1979, as shown in a report with five people meeting at a private address, [UCPI0000013614]. This report notes that the Plumstead branch is also coming under criticism from the district organisation for being lax in its paper sales. The Inquiry noted that Biggs was paper sales organiser for almost year.

ANTI-RACISM CAMPAIGNS

On 12 December 1979, William Biggs of Plumstead was a guest speaker at the Greenwich SWP branch, giving a short speech on the political climate in apartheid South Africa. It is reported that he was able to speak of his ‘personal experiences regarding workings of apartheid’, which prompted a lengthy discussion [UCPI0000013688]. The Inquiry does not know if he did indeed have links or spent time in South Africa.

The Inquiry then draw attention to a report where he chaired a meeting of Greenwich SWP on 25 June 1980, which was addressed by the secretary of the Greenwich branch of the Indian Workers Association [UCPI0000014053]. The latter spoke on racism and fascism, and the oppression experienced by Asians in Woolwich and Greenwich.

In light of this, the Inquiry raised the point:

‘For the question is whether SDS officers, infiltrating the SWP, were tasked to use that position as a stepping stone to involvement with and infiltration of anti-racist groups.’

There are five reports on meetings of the South East London District of the SWP attributed to Biggs. They record financial and membership matters, union representation, newspaper sales, and liaison with SWP affiliated groups such as the Anti-Nazi League, Women’s Voice and Bexley Campaign Against Racism and Fascism.

MOVE TO BRIXTON AFTER THE RIOTS

Biggs’ reporting on the Plumstead SWP continued to at least March 1981, but by June 1981 he was infiltrating the Brixton branch. The Inquiry notes that this was not long after the Brixton Riots which had taken place in April that year.

Biggs was at the inaugural meeting of the Brixton SWP branch in June, attended by nine people. He was, true to form, elected treasurer of the branch [UCPI0000015441].

In October, Biggs was one of thirteen at an SWP meeting to discuss the Brixton Defence Campaign, which had been set up to support those arrested in the Brixton Riots [UCPI0000016622]. They agreed to organise pickets of courts in support.

WIDE-RANGING REPORTING

The Inquiry notes that Biggs’ reporting covers a variety of protests on different topics, from local policing, the Right to Work Campaign, harassment of SWP paper sellers by the National Front, support for Irish hunger strikers, and a picket of Eltham Police Station on second anniversary of death of Blair Peach, who had been killed by police at an anti-fascist demonstration in 1979.

There is also reference to a May 1980 march organised by local Trades Councils in south east London and the Amalgamated Union of Engineering Workers. Among those listed as attending is MP Guy Barnett [UCPI0000013983], which is another example of the SDS breaching the ‘Wilson Doctrine’, a rule that MPs should be informed if they are subjected to State surveillance.

As with other undercovers, Biggs reported on individuals as well as groups. An August 1979 report [UCPI0000011422] singles out someone who is an active shop steward in construction union UCATT who apparently boasts of contacts with the Provisional IRA. Another, in April 1978, states that a Plumstead SWP branch member was a porter and secretary of the hospital branch of the National Union of Public Employees (NUPE) [UCPI0000011911].

In June 1981, Biggs reports on a gay member of Brixton SWP for whom a photograph is supplied [UCPI0000015431].

BEXLEY ANTI-NAZI LEAGUE & OTHER CAMPAIGNS

As interest in anti-racism campaigns among the left was growing, Biggs’ reporting repeatedly touched on the issue. This includes the SWP affiliated Anti-Nazi League (ANL) from 1978 to 1981 and, through his involvement with them, other issues too.

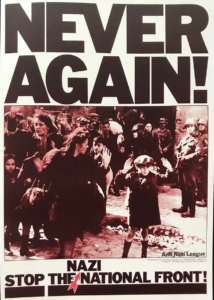

Anti Nazi League ‘Never Again’ poster, 1978

One report is of the September 1978 inaugural meeting of Bexley ANL, at which the Assistant General Secretary of NUPE is a speaker on anti-racist activities within trade unions [UCPI0000011472].

Biggs attended other Bexley ANL meetings, and reports on a picket they organised in aid of the Blair Peach Memorial [UCPI0000013500].

The Inquiry also pulled up a report of February 1981 [UCPI0000016486] when the ANL protested at Deptford Police Station to highlight police inaction in investigating the New Cross Massacre, when thirteen young black people died in a fire at a house party thought to be an act of arson.

Biggs also reported on both the Greenwich and Bexley Campaigns against Racism and Fascism (CARAF). He was at the inaugural meeting of Greenwich CARAF in March 1978 [UCPI0000011917] and recorded who attended a July 1978 event protesting against racist attacks in Lewisham [UCPI0000011330].

REQUESTS FROM MI5

Towards the end of his deployment there were requests for information from MI5 on SWP groups in south London, including on particular individuals. For instance, a 1981 memo [UCPI0000028839] notes the Security Service’s interest in:

‘[the SWP’s] future policy direction, particularly as regards blacks.’

The Inquiry says it will be investigating the degree to which the Security Service influenced SDS deployments.

QUESTIONABLE VALUE

The Inquiry notes three annual appraisals of Biggs by his managers for 1978 [MPS-0743908], 1979 [MPS-0743907], and 1980 [MPS-0743906], calling his work ‘useful’ and noting he is well regarded.

However, the Inquiry’s opinion of Biggs is not so generous:

‘Although some of HN356’s reporting seems likely to have been of some use to the policing of public order, other reports, taken in isolation at least, appear to us to be of questionable policing value.’

Written witness statement of ‘Bill Biggs’

Evidence from witness:

‘Paul Gray’

(HN126, 1977-82)

Most of the day was taken up with evidence in person from ‘Paul Gray’ (HN126, 1977-82) who infiltrated the Socialist Workers Party and Anti-Nazi League.

Unlike the other former spycops we’ve heard from so far, Gray’s evidence was only audio-streamed to the live hearing room, so those who attended were not able to see his facial reactions (or, inexplicably, those of the Inquiry Chair, Sir John Mitting, and the lawyers).

What did come through the audio was his irritation and exasperation at being asked all these questions by the Counsel for the Inquiry. He failed to answer many of them, and often gave obtuse replies to straightforward questions. There were multiple discrepancies between what he’d put in his written statement, and what he said today (as recorded in the transcript).

There was a pattern to Gray’s questioning. He was taken back to his own witness statement to refresh his memory, and would then be shown a series of reports to illustrate or, more often, contradict what he had written.

He used a wide variety of defence mechanisms to fend off questions and avoid answering them, including one that we are very familiar with now: (selective) memory loss, ‘I can’t remember’, ‘I don’t recall’, ‘it’s 45 years ago’.

He interrupted the Counsel for the Inquiry with complaints that she had misread or misunderstood things, even when she hadn’t. He complained about being ‘confused’ by his own words, and came across as both evasive and pedantic, sometimes just responding with things like:

‘If I wrote that, it must have been what I thought at the time… If it says so in the report, that is what happened.’

Gray also denied accountability for or authorship of a number of reports, on the grounds that his signature wasn’t on it (although it had been signed by Chief Inspector Mike Ferguson, who was in charge of the SDS at the time), or that he wasn’t ostensibly a member of the target group on the date of the report.

His strangest excuse was that he wasn’t responsible for his own witness statement – saying several times things along the lines of:

‘I can’t remember writing this. You’ve got to remember that this was written for me, and not all of it is in my type of English.’

This confirms what has long been suspected – that the State’s lawyers ‘helped’ the former spycops to write their statements for the Inquiry.

Counsel for the Inquiry responded:

‘Alright, but this is a statement that you had a chance to review before signing it; is that right?’

We note that Gray had begun his testimony by confirming his written statement as ‘true and accurate to the best of my knowledge and belief’, shortly after making an oath on the Bible to tell the whole truth, so it’s surprising that he doesn’t appear to have read it closely at all.

Gray worked in the Metropolitan Police’s Special Branch for nine years before joining the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS). We know that he spent at least one of those years in ‘C Squad’, whose remit included gathering intelligence on left-wing groups.

According to his police service record, Gray was posted to its ‘Industrial section’. However, he now disputes this official record, claiming that he didn’t work on C Squad at all until after the SDS, when he joined it as a ‘senior officer’. He also seemed to deny having anything to do with the Industrial section.

He remained within the Branch for the rest of his career in the police. He described the Branch in his statement:

‘it was a small, collegiate work environment, everyone knew everyone else, and we all called one another by our first names.’

He says he was first invited to join the SDS by an undercover, who was a friend of his:

‘He said that I would be absolutely ideal for the job, and that I should join up.’

Gray explains that he didn’t take up the suggestion at that time, due to personal circumstances, but decided to join the spycops a few years later, in September 1977. By then, this friend had left the SDS and moved back to other Special Branch duties.

However, Gray says that he was familiar with the SDS supervisors of the time, as well as the senior officer (thought to be Ken Pryde, HN608) who formally offered him the job, after a short interview.

He says he remembers little of that half-hour interview, but is adamant that he was told his anonymity would always be protected.

MARITAL STATUS

Gray wasn’t asked about his marital status, going on to say:

‘Most of my colleagues, including those who were already in the office of the SDS, knew my home arrangements, and we all used to socialise together, with wives, many times. So yes, they did; they were aware.’

Asked why he’d said ‘I thought that you had to be married’, he explained that he’d assumed that all of the spycops were, until he was deployed and met one who wasn’t.

Having ‘a secure background, a secure home’ and ‘someone to come back to, after a long weekend or a long day’ was considered important, ‘so that you didn’t go round the bend, quite honestly.’

He doesn’t think that anyone spoke to his wife about the possible impact of this new role on her and his family life. He doesn’t recall what he was allowed to tell her, though she and other wives of undercovers did know the squad was nicknamed ‘the Hairies’.

A LETTER FROM HIS WIFE

The Inquiry then displayed an astonishing piece of evidence – a letter sent anonymously to then Metropolitan Police Commissioner, Sir David McNee, in 1980 [MPS-0726912]. It contained accusations about the sexual conduct of SDS officers, on police property, makes mention of the National Front, and is signed ‘an ex-friend of the Hairies’. The police opened an investigation into the letter.

By this time, Gray had met, and moved in with, a colleague from the Yard, and divorce proceedings were underway. The police suspected that his wife was responsible for the letter, so ‘discreetly obtained’ a sample of her handwriting to analyse. The report says it is ‘highly probable’ that she was the author, and describes a visit being paid to her home.

The Met’s main concern is avoiding her taking these allegations elsewhere, and revealing the existence of the secret spying unit, rather than their veracity or the impacts on her.

Gray says that following this, he offered to resign, but his senior officers (then Barry Moss and Ray Wilson) persuaded him not to. He says they were fully aware of his new relationship; they all knew the woman, and that he had moved in with her. He later married her.

Did he have any sexual relationships in his undercover identity?

‘Absolutely not… It was something I would never have done. And none of my colleagues at that time were expected to.’

STOLEN IDENTITY

Like other recruits to the SDS, Gray spent some months in the back-office before being deployed.

He got to know ‘Bill Biggs‘ (HN356/124, 1977-82), who was a few months ahead of him in the process, and learnt a lot from him. One of these things was the SDS’ preferred method of creating a false identity – locating the birth certificate of a child who had died at a young age.

Gray says he was instructed (by Chief Inspector Ken Pryde) to go to the government’s birth registry at St Catherine’s House and find a name to use, and Biggs was sent to help him. He chose to steal the name of ‘Paul Gray’, whose birth date was close to his own.

He does not remember any discussion about this practice, or being given any other options.

Gray explained:

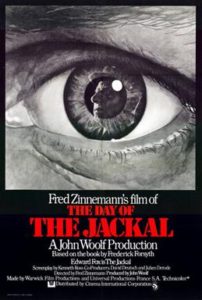

‘We’d all watched “The Day of the Jackal” a couple of years earlier, when it came out, and that’s how the identity was done in that.’

Frederick Forsyth’s best-selling book including identity theft of dead children had come out in 1971, the film in 1973.

However, in his written statement, Gray suggested that this practice had been ‘thought up’ by the unit’s founder, Conrad Dixon.

Asked again about this at the end of the day, he said he’d looked up the film on Wikipedia and now assumed that was the source of this particular tradecraft.

All in all, he remains of the view that this practice was:

‘a sensible precaution, just in case someone decided to look you up.’

The undercover says that he didn’t do any research into the family of the real ‘Paul Gray’, and didn’t give much thought to the possibility that they might find out about his identity’s theft. Asked if he felt uncomfortable about it:

‘I don’t think it ever crossed my mind after it had all been okayed with the people in the office.’

Although he created a detailed back-story for ‘Paul Gray’, he says he never needed to use it:

‘I probably would have bluffed my way through the conversation had anyone asked about my background.’

He said nobody ever ‘tested’ his false identity.

EXPOSURE

Gray’s belief that identity theft was ‘sensible’ is at odds with the fact that it could fail spectacularly. Though it provided the spycop with a real birth certificate in case suspicious comrades checked, it also meant they had a death certificate that was just as easily found. And it happened.

Just before Gray’s deployment began, SDS officer Richard Clark (‘Rick Gibson’ HN297, 1974-76) was presented with a copy of the real Richard Gibson’s death certificate:

‘It was very much in all our minds when we joined the Squad.’

He said that he had heard rumours about why Rick had ‘come off in a hurry’, but was reassured by the SDS office staff:

‘That it would be okay; and there were other parts of his deployment that I would never have gone into, so in my mind it didn’t matter.’

It became clear that Gray had come to believe that it was the relationships Clark had had whilst undercover that caused him to be confronted.

However at the very end of the day, when asked to clarify this matter, Gray contradicted what he had said before. He now claimed that he only heard these rumours prior to joining the SDS, while he was working in the wider Special Branch. He went on to say that by the time he joined:

‘Everybody had forgotten about it at that time… we were all getting on with our postings and we were making sure we didn’t make the same mistake.’

The Inquiry asked how they were sure they were not making the same mistake unless everybody knew what had gone wrong, the only thing Gray had to say was:

‘We knew we should try and not have intercourse with somebody … who was one of the subject of ours undercover.’

He remains convinced that his contemporaries were all aware of the rumours, as many of them had been in the SDS with Clark.

TRAINING & GUIDANCE

During his time in the SDS back-office before going undercover, Gray read reports including those from deployed officers. He also attended the regular meetings at the SDS safe house (twice a week by that time), where he talked to them about their experiences and was given advice on what he should be doing once in the field.

‘After the meetings I would go and have a pint in a local pub with the officers who were undertaking deployments in groups similar to the one that I would be deployed into. If they did not drink, they would just have a chat with me at the end of the meeting at the SDS cover flat. They would give me advice on what I should be doing when I went into the field.’

According to him, this was the usual way for SDS officers to learn – from those who had already been deployed.

At this time, his managers included two former undercovers: Mike Ferguson and ‘HN68’ (who had used the cover name ‘Sean Lynch’ in his deployment).

There was no formal training, and he was not provided with any kind of manual or handbook. Indeed, Gray claimed he was surprised anyone might think there would be any formal training or rules to follow:

‘We were police officers. We were expected to use our common sense and judgement. You learnt on the job.’

The only guidance Gray can recall being given is to telephone the back-office if he was ever arrested. He wasn’t told avoid committing any crimes, and says he tried to avoid any violence at demonstrations.

He does not believe he ever saw the 1969 Home Office Circular, which prohibited undercover officers from being involved in legal cases, nor did he receive any formal guidance on other legal or ethical issues.

Despite going on to far more senior roles in the police, Gray said he had no understanding at all of the phrase ‘legal professional privilege’ – meaning confidentiality between lawyers and clients, which should not be spied on by police – and added that this didn’t exist in his day, which is untrue.

What about relationships (in the widest sense, including friendships) with those he spied on?

‘I was allowed to get close.’

Gray was explicit about the spycops being encouraged to socialise with those they spied on; it was recognised as an excellent way of gathering information.

He also talked of people getting lifts in his cover van and that he visited some people’s homes and being invited in for cups of tea, for example when dropping off copies of the ‘Socialist Worker’ newspaper.

‘I was never aware of anybody who worked at the same time as me having a sexual relationship.’

He wasn’t told not to though:

‘It was never mentioned that we were not able to have relationships, but there again, it was not expected… And I’m sure if I’d heard about anyone else who was having a relationship, I’m afraid I would have had reported it to the office.’

Gray cheerfully admitted to drink-driving while on duty, claiming that this was just ‘common sense’:

‘If you’re going to go to the pub after a meeting, or a lot of the meetings were held in pubs, you would have a couple of pints, and that you were going to drive home. You had to deliver all the people in your branch back to where they lived. So that’s as far as breaking the law was concerned.’

He went on to make excuses for this criminality on the grounds that the beer was very weak in those days. He then said he had his cover job as a driver as an excuse to leave the pub early if he wanted to.

Later on, Gray made a comment about how people tended to buy their own drinks in those days, rather than rounds, making it easy to hide how much or little one was drinking. However he didn’t say that he actually did this himself.

CLOSE & COSY WITH SENIOR MANAGERS

It also emerged that Gray had a particularly cosy relationship with the unit’s managers, in particular Mike Ferguson and ‘Sean Lynch’. In his statement he said they were:

‘absolutely brilliant, very experienced, they would always be there if you needed them.’

Speaking to the Inquiry, he clarified what he meant – they had experience of being undercover (rather than of being managers), which they passed on to him and the others – and called them ‘good all-round officers’.

He knew both men before joining the SDS. It sounds like he socialised and played squash with them regularly:

‘It is difficult to separate what I learnt from them on the squash court rather than in the office. I mean, we were big friends.’

Asked if the other undercovers had a similarly close and supportive relationship with the SDS management, he said:

‘I’d like to think so, but I don’t know.’

OTHER SPYCOPS – IGNORANCE IS BLISS

Gray attended the spycops’ weekly gatherings every week starting when he was working in the back office. Since the evidence of ‘Graham Coates’ (HN304, 1976-79), who vividly described what amounted to a sexist culture at the SDS, the Inquiry has been asking other spycops about their experience with this kind of ‘jokes’ and ‘banter’.

Gray claimed he didn’t experience any of this offensive language, either at the safe-house or in the pub afterwards, saying:

‘I wouldn’t have approved of it and I quite honestly can’t imagine any of the colleagues that I knew doing anything of that sort.’

He also claims not to have known about anyone at that time indulging in sexual relationships. The Inquiry noted that he served alongside ‘Vince Miller’ (HN354, 1976-1979) who had admitted to at least four sexual encounters. Gray says he was surprised about this, and denied all knowledge:

‘I never knew what was going on, but then again, I wasn’t in his circle.’

He went on to claim that he didn’t even know that ‘Vince’ had infiltrated the same target group as himself, the Socialist Workers Party (SWP).

In his statement, Gray described the work of his fellow spycops in glowing terms, saying they did an ‘exemplary job.’ Asked if he considered this still to be the case, now that he’s learnt about ‘Vince’ and the way he abused his position, Gray said yes.

When questioned about a number of other undercovers who deployments overlapped with his, he denied ever hearing anything untoward. Rather, they didn’t talk about what they actually did in their deployments:

‘I hadn’t a clue what the other officers were doing… even the ones who were in the same group as me. It wasn’t something that was talked about a lot.’

Asked more about his contemporaries, and who he was closest with during that time, Gray recalled sometimes going out for curries together in a group:

‘We would try to carry on normal life as much as we could away from our undercover jobs. We would never talk about our undercover jobs when we met like that, unless you needed some advice from someone who had done it before. Generally, you would have absolutely no idea what the others were doing.’

HIS ROLE AT GRUNWICK

Another inconsistency emerged between Gray’s written and oral evidence when he spoke of the long-running Grunwick industrial dispute. According to his statement:

‘Several of my SDS colleagues attended and reported on the Grunwicks disputes.’

How did he know this, if they never spoke about what they were doing?

He kept ducking the question, causing the Counsel to ask it three times. He eventually conceded that it was possible that Grunwick had been discussed at the spycops’ get-togethers but insisted that he ‘didn’t see their reports’.

This strained his credibility, especially as he said:

‘One of the reasons that I was moved to that particular part of London was to replace an officer who had in the past reported on Grunwick. You have got to remember, Grunwick went on for two years, every day, and I don’t think I submitted any reports, because most of the work done with myself was going to the early morning pickets of the Grunwick factory and giving detail beforehand to the office of how how many people were likely to be on the streets, whether it was going to be a big one or a small one, and that was all done by telephone. That’s why probably I say I don’t recall submitting any reports.’

Police press back pickets as buses of strike breakers arrive, Grunwick dispute, London, July 1977

Gray kept saying that he didn’t write any reports about Grunwick himself as his reporting was all done by telephone.

He added:

‘I didn’t know what my colleagues were doing. You might see one of them. We’re talking about 7 o’clock in the morning when the Grunwick employees were being bussed in. On some days, it was a big punch up, on other days there were hardly any pickets there at all. But the pickets came from all over the country, and quite notable people were attending.’

VISITS FROM THE TOP BRASS

The spycops were visited in their safe-house by senior police officers, including a Deputy Assistant Commissioner (probably Robert Bryan), and on one occasion by an Assistant Commissioner for Crime.

Gray recalled that the latter:

‘was very shocked by seeing us and hadn’t a clue what we were doing. But we gave him lunch and he went away happy.’

He noted such visits were ‘always treated with a little bit of humour’ and explained:

‘Because if you’re working in a situation in Scotland Yard where everybody looks the same and they’re all doing their job, and you then come out, to a not-very-tidy flat in the middle of nowhere, and meet ten chaps who are smelly, hairy, not very nice, and you are told that they’re your officers, it was a bit of a shock, I think, and that happened on a couple of occasions.’

He assumed that the senior SDS office staff briefed these visitors.

Asked if the shocked Assistant Commissioner for Crime was Gilbert Kelland (1977 – 1984), he said the name of the visitor he remembered was Mastel. The latter was a contemporary Assistant Commissioner, but for A Division – not C – and that is peculiar as he was not in the line of command of the SDS.

THE REPORTING PROCESS

Gray has complained that many of his reports he remembers making are not in the bundle of evidence that the Inquiry has provided him with. If he had anything urgent to report – including information for the Met’s public order department (A8) – he tended to telephone it in.

However, he also submitted many written reports, and it is clear that many of them are missing:

‘There are a hell of a lot of bloody meetings that I reported on that are not in my bundle.’

He says that he would draft what he called ‘current reports’ and then give them to the office staff to finish off, and maybe collate with others. Earlier he said that Special Branch – beyond the Special Demonstration Squad – would sometimes consolidate intelligence from different spycops into single reports.

At the end of his deployment, Gray was asked to bring the files of various individuals up to date before he left the unit. He described this as ‘topping and tailing’ reports, by writing down everything that was known about the subject; where they lived, how much spare time they had, what they did with it, how often they had people over, how much involvement they had with campaigning, etc.

The Inquiry illustrated this May 1982 report on a member of Kilburn SWP and West Hampstead CND [UCPI0000018134].

Even the notion that people were politically inactive for years was seen as an important input to an ‘up-to-date’ report, and these files would be retained (for example [UCPI0000018131]).

Gray complained that the examples shown today were ‘not representative of an ordinary up-to-date report’, and Mitting promised to examine the others.

REGISTRY FILES

He explained the significance of the numbers that appear on the sides of these reports: these were Registry File reference numbers added by office staff, after they’d run a check on the names of any individuals and groups mentioned.

Gray also clarified that the police had a special photography unit, who took photos at demos and meetings. Sometimes an album of these photographs would be shown around at the safe-house, for anyone there to help with identifying the people in them.

‘SUBVERSION’ & THE SWP

Gray was sent to North West London, as another undercover had just left the area:

‘probably because at that time, we were having a lot of trouble with getting the right numbers of police officers on the streets in the mornings at Grunwick.’

He also stated:

‘I was not tasked beyond being told to infiltrate the SWP’

In his witness statement he said that the SWP:

‘was a revolutionary group which was involved in demonstrations. They were willing to achieve that by whatever means possible, and did not believe that the ballot box was the only way. They were dedicated to the downfall of the government at the time.’

He accused them not just of being ‘subversive’, but also of presenting a ‘challenge to public order’ and being ‘involved in criminal activities.’

The Inquiry sought to clarify what he meant by these assertions. How did he know they were ‘subversive’? Did he ever witness the SWP or its members doing anything to ‘bring down the system of government in this country’?

His answer was frankly bizarre; he began talking about their participation in anti-fascist demonstrations and the ensuing conflict in Brick Lane on Sundays, when members of the fascist National Front would confront SWP newspaper sellers, saying it was ‘quite violent’ and ‘very, very unpleasant’.

When asked if that had anything to do with subversion, he replied:

‘It could be. Whatever subversion is, I don’t know.’

We were shown a report from September 1979 [UCPI0000013385], of a meeting of the SWP’s NW London District Committee. According to this, the SWP was ‘at an all-time low’, with only 3800 members nationwide, to be suffering from apathy, and low circulation figures for the Socialist Worker newspaper. Gray said he did not remember this, nor any discussion with his managers about his continued deployment in the group.

In his statement, he says:

‘it was the role of Special Branch to report on subversive activity, but it was the role of the security services to deal with it, not the police. The main role of the SDS was intelligence gathering to assist with public order policing.’

He knew that the Security Service (MI5) was interested in the spycops’ work, pointing out that they were sent a copy ‘of everything that we produced’ and explaining the ‘Box 500’ stamp in the corner of the copies seen by the Inquiry indicates this.

We saw examples of ‘Box 500’ requesting information, including a document dated January 1980 [UCPI0000013713] which contains personal details about a member of the SWP’s Kilburn branch being treated in hospital following a car crash.

Did he ever think of the SDS – or the Met police more widely – as being subordinate to MI5?

‘It never crossed my mind.’

RACISTS & VIOLENCE

In his statement, Gray said that there was ‘always a sub-group’ who were looking for trouble, but that he chose to stick with the people who chose to avoid aggravation so, as a result, was never caught up in violence or injured at any demonstrations.

Asked if he ever considered confining his reporting to those who were getting involved in the violence, rather than the peaceful ones, he said he didn’t. Although he admits that many SWP members were entirely peaceful and law-abiding, his excuse was that he had to report on the group as a whole.

Later on in his written statement, he wrote:

‘I suspect that all of them had run-ins with the police’

However, he said he didn’t know if any of them were arrested. He defined ‘run-ins’ in an unusual way – describing groups of activists running at police lines to break though them – but denied taking part in this practice himself, saying that all he got involved in was:

‘linking arms and trying to stick together with my comrades.’

Why did he describe the SWP as ‘a leading group in the public order field?’

Gray said their newspaper sales were prolific, and still are. They were active, they went to a lot of demonstrations and pickets. There was disorder. In his written statement, he claimed that they were involved in criminality, and he frequently saw them engage in violence.

When questioned more about this, the only example he could provide was the violence he saw at Brick Lane in East London. He spoke about them throwing missiles – ‘bricks, rubbish bins, anything that was going’ at the National Front (NF).

Despite admitting that the NF deliberately chose that place to demonstrate because it was a predominantly Asian area, and the NF ‘wanted to get rid of them’, and ‘the Bangladeshi restaurants and shops would get smashed up’ by the NF. Yet he also insisted that the violence he saw ‘was provoked by both sides, and the police had to keep them apart.’

The only other example cited of disorder at a demonstration dated back to the March 1968 protests against the Vietnam War outside the US Embassy in Grosvenor Square.

There are no reports on any violence of this kind in his entire deployment. Gray claimed this was because the spycops provided ‘pre-emptive intelligence’ so were able to prevent such violence from taking place.

In response to this, the Inquiry laid out some other examples of his reporting, which were not ‘pre-emptive’ at all, but about things which had already occurred.

One such report concerned a car being used by a local Anti Nazi League (ANL) group who went around painting over racist graffiti [UCPI0000011447]. Gray said the security services would have been ‘very interested’ in the details of the car and its owner.

In contrast, it appears that the police weren’t interested in taking action against the NF, and the SDS did not infiltrate them. This was confirmed by Gray, in his own words, when talking about that letter written by his wife, in which she mentions spycops infiltrating the extreme right wing, he said:

‘She didn’t get it from me, because we weren’t, in those days.’

UPWARD MOBILITY IN THE SWP

The Inquiry traced Gray’s journey through the SWP’s hierarchy, with the help of some more documents.

The first SWP meeting he attended and reported on seems to have been a meeting of the Cricklewood branch in February 1978 [UCPI0000011859]. He explained that this was the only branch of the party in the area at the time, but again failed to answer the Inquiry’s question: did the SDS view infiltrating the SWP as a ‘stepping stone’ to other groups?

The next report [UCPI0000011354] was from a much smaller meeting of the Cricklewood Branch Committee, in July 1978. This took place in someone’s home, and elections for the Committee took place. Gray was voted in as a committee member – he is listed as the ‘Socialist Worker Organiser’.

He now claims that he had no idea this election was due to take place, and that he was nominated from the floor, and had no way of excusing himself or contacting the office for authorisation before accepting it. He suggests that the reason for his nomination was that access to a vehicle was essential for the role of moving a lot of newspapers. In any case, he believes he was a trusted member of the group by then, and his managers were happy about this.

In January 1979 he was elected to the North West London District Committee [UCPI0000013111]. He is adamant that he did not volunteer for this either, but he knew in advance that he would be appointed, and says this:

‘It’s better not attract attention by putting up your hand.’

A week later, at a meeting of seven District Committee members [UCPI0000013123], Gray became the District Organiser responsible for newspaper distribution. He was tasked with organising regular meetings with Branch Organisers across the wider area. Partly, it seems, because he had a van.

He explained that he would turn up at their Branch meetings and talk to them about their paper sales. This meant he could gather a lot more intelligence, about a lot more people. Asked if this gave him more influence over Branch Organisers, he responded by talking about how hard it was to collect money for papers sold.

When asked if joining the District Committee could be considered a step up in the SWP hierarchy, Gray claimed he ‘never thought of it that way’ and repeatedly claimed that he had little influence over decisions, he just transported papers around.

We saw a few more reports about paper sales and party members being exhorted to sell more. A National Organiser came to the District Committee meeting in September 1979 [UCPI0000013435], and proclaimed that selling the ‘Socialist Worker’ was the most important duty of any party member, and told Gray he should be doing more to boost sales, including spot checks on the branches in his patch, causing an ‘embarrassed silence’ in the room. Gray himself did something similar in April 1979 [UCPI0000021170] just before the General Election.

After some discussion about the his position in the party structure and how it compared with others, for example that of Branch Secretary – during which Gray absurdly claimed that there weren’t ‘any hierarchies around’ in the SWP – we saw a report [UCPI0000014064] of him chairing a District Committee meeting in June 1980.

Paragraph 5 of this report makes interesting reading:

‘The meeting was informed that it was feared Acton SWP had been infiltrated by a “spy”… it was decided that he was too inefficient to be a member of the Special Branch, but was probably from the National Association for Freedom.’

Gray claims to have no recollection of attending this meeting at all. Not unreasonably, Counsel to the Inquiry asked: