UCPI – Daily Report: 23 January 2025 – HN32 Michael Couch

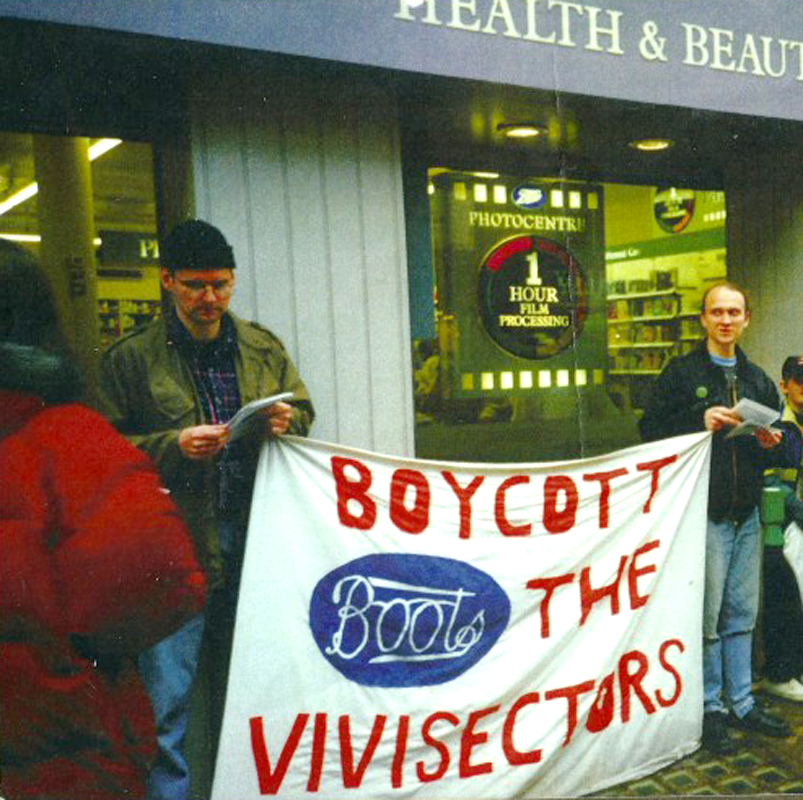

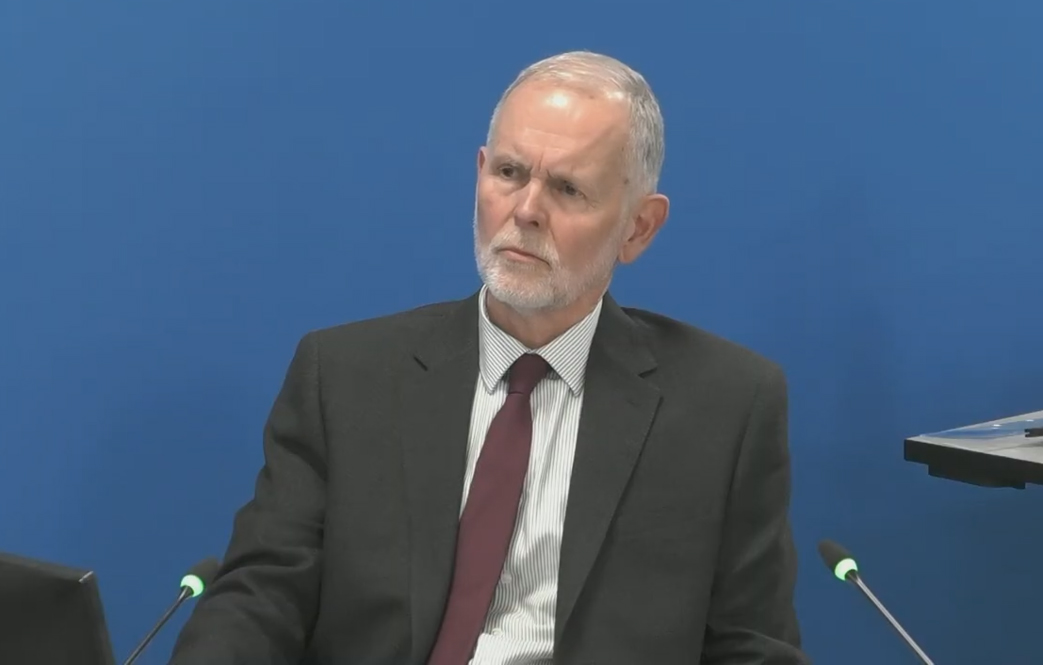

Special Demonstration Squad officer HN32 Michael Couch gave evidence to the Undercover Policing Inquiry on 23 January 2025.

Special Demonstration Squad officer HN32 Michael Couch gave evidence to the Undercover Policing Inquiry on 23 January 2025.

He had never been an undercover officer himself (in fact he turned down the offer), but he was in a key admin role close to the spycops in the mid-1980s.

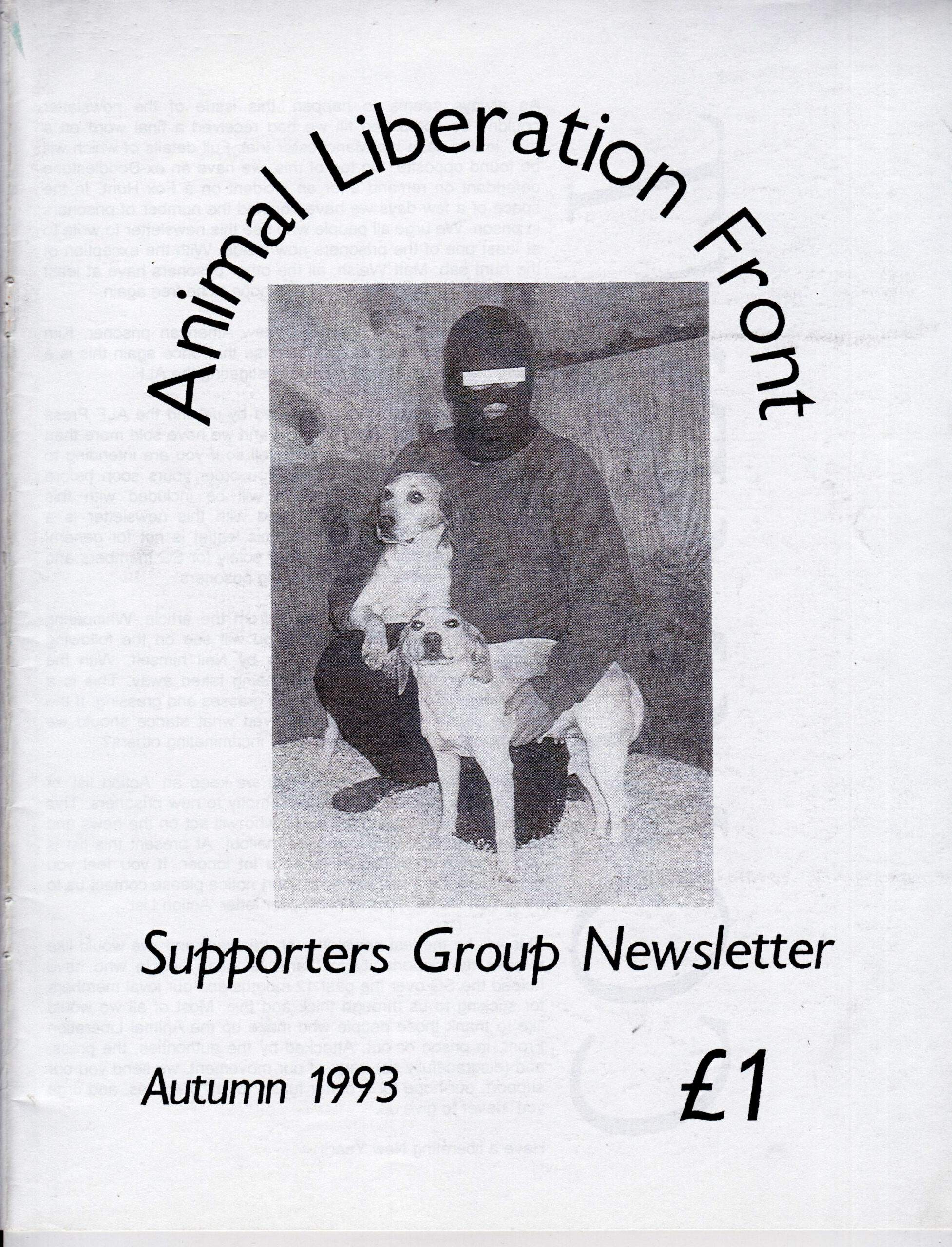

At that time, HN10 Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’ was infiltrating an Animal Liberation Front cell and planting an incendiary device in a Debenhams department store.

RECAP

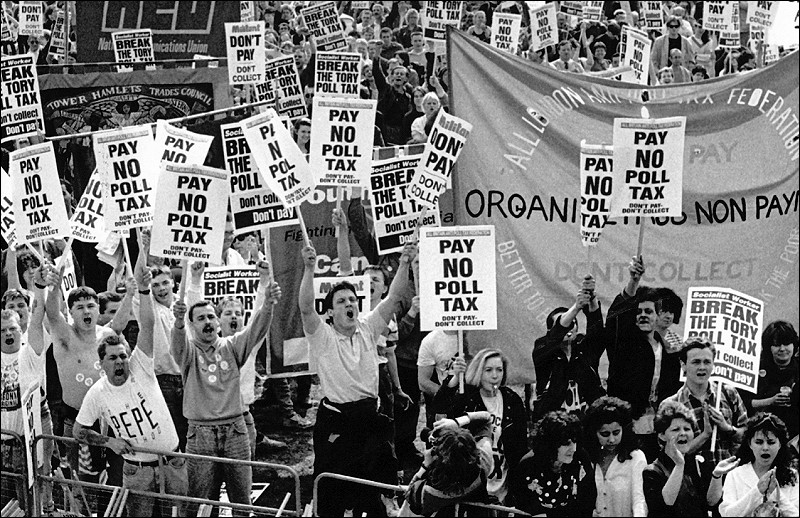

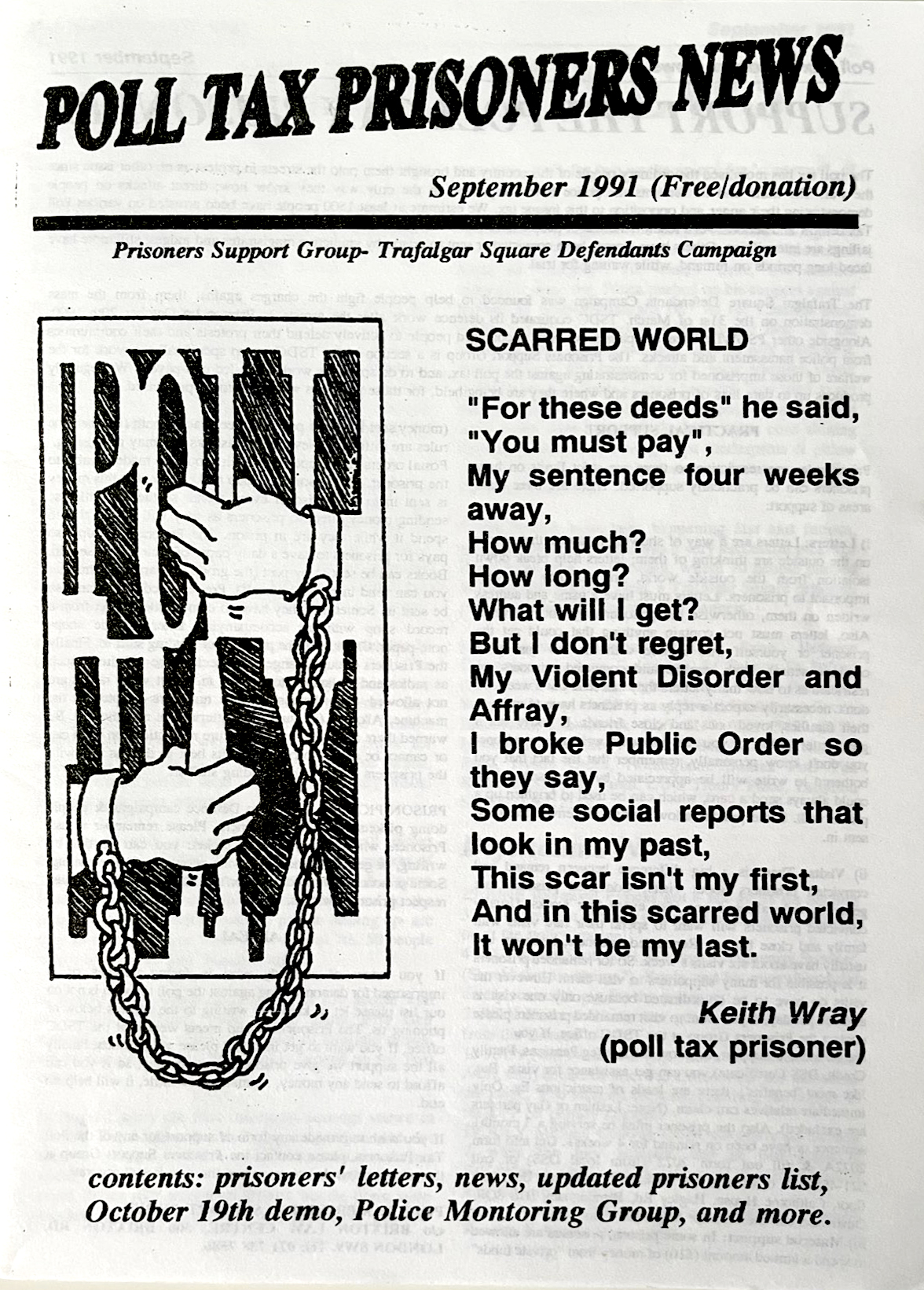

This was the Monday of the ninth week of ‘Tranche 2 Phase 2’, the new round of hearings of the Undercover Policing Inquiry (UCPI). This Phase mainly concentrates on examining the animal rights-focused activities of the Metropolitan Police’s secret political unit, the Special Demonstration Squad, from 1983-92.

The UCPI is an independent, judge-led inquiry into undercover policing in England and Wales. Its main focus is the activity of two units who deployed long-term undercover officers into a variety of political groups; the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS, 1968-2008) and the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU, 1999-2011). Spycops from these units lived as activists for years at a time, spying on more than 1,000 groups.

OFFICER WHO SAID NO TO BEING A SPYCOP

Couch joined the police in 1967, and Special Branch in 1973. He knew that there were undercover officers who reported on political campaigners because he was asked by one of the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) managers, HN294, if he fancied going undercover himself. He says this was an informal chat, rather than a definite invitation. He declined, in part because he was going through a divorce at the time.

He also says he didn’t feel this work would suit him. He knew it was a time-consuming role that would drastically impact upon his social life. Specifically, at that time he was on the Met rugby team and didn’t want to give it up!

He saw many of the reports produced by undercover officers during his time in Special Branch, and says he understood the types of groups that they infiltrated.

THE BACK OFFICE ROLE

He finally joined the Squad in April 1983, as its ‘admin sergeant’, after being asked by HN99 Nigel David Short. Short explained the role to him: tidying undercover officers’ reports and making sure this intelligence was passed on. He thought it sounded interesting, so accepted, and ended up staying in the unit till July 1987.

There were always two sergeants in the SDS back-office, and the other handled the unit’s finances (mostly vehicles and expenses claims). In 1983, this was HN45 ‘David Robertson’. Couch was given the finance role in 1985, when Robertson left, and HN61 Chris Hyde joined the unit as its new admin sergeant.

These back-office sergeants attended the meetings that took place every week in the spycops’ safe-house. They answered the phones in the office when the undercovers rang in every day.

Couch would pass on requests from any of the main squads within Special Branch to spycops managers and field officers. He also accompanied the Detective Inspector on trips outside the Met police area.

The two back-office sergeants did not consider themselves as ‘managers’ but rather as ‘close colleagues’ of the undercovers, as they usually had the same rank.

‘The whole dynamic was fairly informal and relaxed’

He says there ‘was a little bit’ of socialising at the safe house, ‘but not a lot’ because the spycops tended to have activist meetings and events to get to.

He says they didn’t generally talk about the groups and individuals they were spying on, but talked about everything else.

HN25 ‘Kevin Douglas’ criticised Couch’s admin sergeant colleague HN61 Chris Hyde, saying he was ‘too close to members of the field’ and ‘liked to be one of the chaps, one of the boys’. Couch rejects this description. He says there was a clear distinction between the undercovers and the backroom staff.

WELFARE AND CAMARADERIE

Couch’s role also included a pastoral, welfare element. He would mix socially with spycops on days off, go running with them, sometimes play badminton or squash before and after work, and go out drinking with them.

He recalls that unit manager HN115 Tony Wait often went swimming at lunchtimes. Some of the unit went running together at the track in Battersea Park. He agrees that these shared sports contributed towards a feeling of camaraderie in the unit.

There would also be away days when the whole squad would go off to the races, the beach or Boulogne.

‘Just general good fun and being human, if you like’

Couch remembers that the SDS held Christmas dinners for the spycops officers and their wives – he took his along.

It’s clear that Couch considered his relationship with the other spycops was a good one. He says he was friendly, and if spycops had any worries they could come to him and he would pass it on to management, if they didn’t want to go directly to their superiors. He claims not to remember the specifics of any instances of this.

WRITING THE REPORTS

The spycops didn’t get any formal training about how to write their reports after joining the SDS. Prior to deployment they would read the reports of officers already in the field to get an idea of the style and tone of SDS reports.

No formal minutes or notes were taken at the meetings in the spycops safe-house, but Couch says he sometimes took notes for himself.

He would look at the notes submitted by the spycops and try to speak to them in person if anything wasn’t clear. He says he would read through draft reports and check them to ensure they made sense before sending them off to the Special Branch typing pool.

He says this typing was done by the ‘woman in charge’ of the typing pool and not shown to anyone else there. He would check it again when the typed version came back. It was then handed up to the spycops managers to review and sign.

Couch says he can’t remember any instances of a senior officer criticising a report’s value, or refusing to sign off on one.

Every hand-written spycops report would be typed up and disseminated – delivered to a Squad Chief, with a copy going to the Security Service too. He says that, while it’s possible that some that wouldn’t have gone out, he can’t remember that ever happening at all.

This means that pretty much every single hand-written report he ever received would automatically be disseminated. This is extraordinary, given the amount of personal and pointless information we’ve seen in reports. One officer after another has told the Inquiry their job was to hoover up all information possible so that their superiors could sift through and decide what was important, yet it appears that those above them didn’t have any discernment and just swept up and filed everything that was given to them.

SCANT SUPERVISION

Couch said he didn’t have any direct dealings with the Security Service (aka MI5) during his time in the SDS. Instead, it was the Detective Inspectors who liaised with them, rather than the Sergeants or Constables.

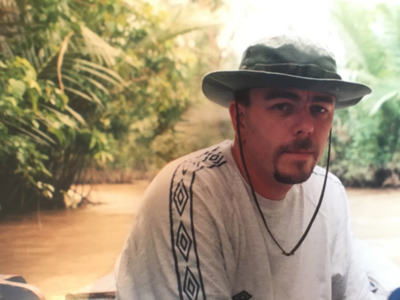

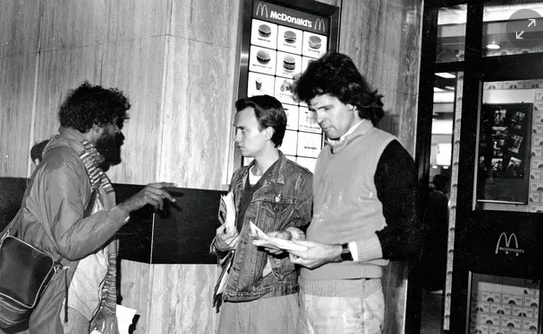

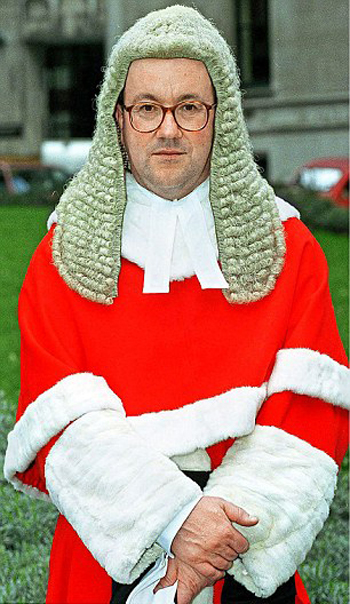

Bob Lambert giving evidence to the Undercover Policing Inquiry, December 2024

In his evidence, HN10 Bob Lambert claimed that the SDS reports went through a ‘sanitisation process’, and were routinely edited and altered by the managers. However, Couch says he doesn’t recall this ever happening.

He admits to sometimes suggesting improvements – mostly trivial points, such as spelling or other obvious mistakes – and says he always checked in with the officer before removing anything which he considered irrelevant from their reports, or changing the wording. He insists that it was very important not to change their meaning.

The spycops were expected to phone the office twice a day, primarily for welfare reasons but also to report any urgent intelligence.

Whoever was in the office would hear these phone conversations taking place, and would usually be aware of any important issues that were reported during them.

Field officers weren’t supervised closely. In those days, backroom officers never actually visited the spycops’ cover addresses. Couch says they might let the office staff know if they were going to be away from the cover flat for any reason, but not always.

He doesn’t remember many problems being raised, and says if any of the undercovers had a problem, they could always arrange to meet up with one of the managers to discuss it. He wasn’t privy to the discussions that took place at these meetings.

MARRIED MEN DECEIVING WOMEN

Couch says his understanding of why spycops had to be married came from HN99 Nigel ‘Dave’ Short. It was so they could get back to their usual selves during time off. He firmly agrees that there was a clear idea that the spycops needed an ‘anchor’ back to their real lives.

‘I think it was generally thought by those in charge of the unit… that it was a difficult role’.

He says the office staff had a role to play in keeping an eye on them and making sure their undercover role didn’t take over.

Asked why wives were given such a key role in being an anchor for spycops real lives, and yet apparently got no support for it at all, Couch can’t recall it ever being discussed.

The Inquiry was shown notes taken at a 2015 interview with undercover officer HN88 ‘Timothy Spence’ for Operation Herne, a previous police investigation into spycops. There is a subheading where the word ‘Sex’ is underlined. Below that, there is a note saying ‘Single men – with groups’. This is followed by ‘Only married people – for a reason’.

The Inquiry suggests this means there was an awareness of the risk of sexual relationships and so they recruited married officers to counter that.

Couch rejects that entirely.

‘No, I don’t think so. I think it would just be about having a stable life at home, whether their partners or married or – I don’t think we knew of any sexual activity with undercover officers and the people, groups that they were infiltrating at the time.’

He says this despite the fact that, during his four years supporting spycops, at least five officers he worked with – around half those in the field – are known to have had such relationships with women they spied on:

• HN10 Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’

• HN11 Mike Chitty ‘Mike Blake’

• HN12 ‘Mike Hartley’

• HN106 ‘Barry Tompkins’

• HN155 ‘Phil Cooper’

There is also the significant suggestion that HN95 Stefan Scutt ‘Stefan Wesalowski’ did too (it’s in a document the Inquiry has referred to but, at the time of writing, has yet to publish: reference number MPS-0740935).

And all this, of course, followed a huge proportion of earlier spycops having done the same. This abuse of women is well established as part of the culture of the squad. As their later Tradecraft Manual shows, spycops were given tips by forebears on how to conduct these relationships that they now say they never mentioned to one another.

Couch says he remembers that some of the spycops were in ‘happy marriages’ which they spoke to him about, which would have been a positive influence on them, but admits that this wasn’t always the case.

He agrees with that more should have been done at the time because their undercover life was going to be so different to their conventional married life.

‘It would be very difficult for the officers to turn down an invitation if a member of the opposite sex was keen, I suppose’

Bob Lambert says he was told on a trip to Boulogne that sexual relationships were going to happen, and when they did spycops should keep it casual. Couch went on these trips but says he doesn’t recall this.

Couch’s boss, HN115 Tony Wait, has told the Inquiry there may have been an attitude in the unit that sexual relationships were inevitable. Couch still says it was never even discussed. He describes how the spycops were a tight knit unit, but says it would be very difficult to know what the officers were doing as supervision was so lax.

Couch is specifically asked about each of the four women Bob Lambert deceived into relationships, the son he fathered with one of them, and Lambert’s claim that he told Couch’s immediate superior HN22 Mike Barber. Couch claims to know nothing about any of it, at all.

He says he is now disappointed in Bob Lambert because of the relationships he had undercover.

Couch was very quick to answer questions about Bob Lambert’s sexual deception to say he doesn’t know anything. Too quick, really.

NEW RECRUITS

The two Detective Sergeants usually shared their office with the unit’s latest recruit, who spent around six months learning about the squad prior to their deployment in the field.

On a normal day, Couch would be working on reports, the other sergeant on finance, and the rookie spycop on his ‘legend’. The new recruits would have to arrange for a vehicle and some story of fake employment – ‘generally they would sort that out for themselves’. The SDS arranged for driving licences in their cover names.

Bob Lambert has described helping with reports, adding file numbers to them, and Couch agrees that they would do things like this, adding that he and Lambert would be the ones sent over to Scotland Yard to collect things.

In an appraisal, HN113 Raymond Tucker mentioned Couch’s ‘close supervision of young officers’. He admits that this was true, and says the older officers were ‘more than capable of sorting out their own problems’.

There was no formal training. The new recruits learned from their time in the office (and the weekly meetings). Couch doesn’t think there was a tradecraft manual or equivalent ring binder in his day.

How did they learn how to create their cover identities? He says they mostly learned their tradecraft from those with undercover experience, and this wasn’t something that he had. The existing field officers would share information with the new ones about how to successfully infiltrate a group.

Once they knew which groups they were being tasked to infiltrate, they could read reports about them, and request more files from Scotland Yard.

Although Couch wasn’t directly involved in teaching them about ‘legend-building’, he was around when this was happening. He says he didn’t take part in ‘testing’ the spycops’ cover stories.

Yet in the SDS Annual Report of 1986 [MPS-0728977], it’s claimed that the office staff ensure that the cover identity’s ‘background is thoroughly checked’ before each of the spycops was deployed. Couch admits that he can’t recall ever doing this.

Perhaps his memory is at fault, or perhaps this is another instance of the Annual Report being contrived to tell the Home Office things that sound good so the unit would get its funding renewed.

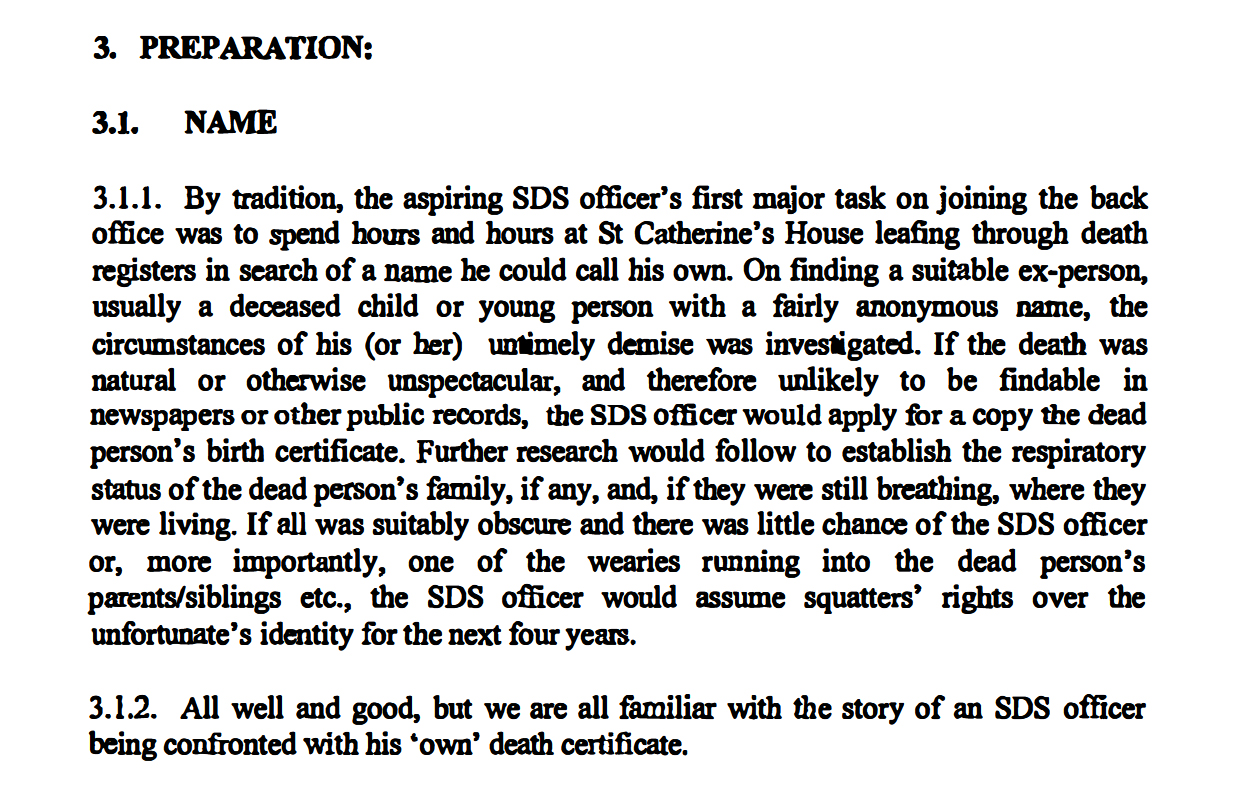

IDENTITY THEFT

Couch also says he can’t recall helping anyone research the family of the deceased child whose identity they planned to steal.

He doesn’t think they ever considered using a different method – such as concocting an entirely fictional cover identity – and says it would have been ‘a lot easier to expose the officer’ if there was no birth certificate in their name. This is simply not true.

When the SDS was founded in 1968, officers made up their cover names. The unit’s theft of dead children’s identities only started in the early 1970s when the method was described in the novel and film Day of the Jackal.

SDS Tradecraft Manual instructions for stealing dead children’s identities, including a mention of the spycops all knowing about an officer being confronted with the death certificate

Since the mid-1990s, when personal data became easy to find online, officers have returned to making up names. The lack of a birth certificate doesn’t appear to have been a problem for any of them.

There are many reasons why someone might not have a birth certificate in the records. For example, if they were adopted, if they were born abroad, if they had changed surname (e.g. if their mother had remarried), or if there was an error in the filing system.

Whereas there is absolutely no excuse for a living person having a death certificate. It is the death certificates that were the final proof for activists exposing numerous officers such as HN297 Rick Clark ‘Rick Gibson’, HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’, and HN596/EN32 ‘Rod Richardson’.

The Inquiry pointed that out to Couch. He said he knew Rick Clark ‘left the unit early’ but says he didn’t know that he was pulled out of the field after his death certificate was presented to him by activists.

This is also odd, given that the SDS Tradecraft Manual of 1993 talks about that incident as a notorious piece of unit lore.

BIGOTRY AND DISCRIMINATION

Next, we see a report [UCPI019617] written by HN67 ‘Alan Bond’ in October 1983, when Couch was processing the unit’s reports. It’s about someone who works in the Socialist Workers Party print shop, who is described as a ‘homosexual’. According to the report he is

‘regarded in gay circles as an unstable and over-emotional partner’.

Couch tried to claim it was worthwhile intelligence, but the Inquiry quickly made him concede it was nothing of the sort.

Q: That’s irrelevant information, isn’t it?

Couch: Well, I – he’s not trusted with his own party. I’d say that that was relevant.

Q: It doesn’t say any words to that effect…. It’s gossip, isn’t it?

Couch: Yes.

Q. There’s no intelligence value in the entirety of what is being reported in paragraph 3, is there?

Couch: I’d say not.

With his defence having failed, Couch then tried to avoid responsibility by suggesting the report had been processed by others.

‘It’s gone, it’s been put through, so nothing we could do about that…

‘I can’t recall reading it in the first place, erm, but it might, I mean just, Mike Barber might well have submitted that because he used to check reports as well, before they were typed up.’

He did admit that if he had seen this report at the time, he probably wouldn’t have challenged it.

He says it was important that spycops reported on private lives. He has no suggestion about who it was important to, though.

He denies Bond’s report is indicative of the spycops’ attitudes towards gay people, saying he never heard any homophobic language from any spycops officers, field or office, whatsoever.

It’s amazing that pretty much every spycop says there was no bigoted language used when talking to one another, even though it’s there in their reports. They expect us to believe that they were upstanding egalitarian chaps who would somehow lapse into bigotry when writing official documents even though it was never part of their thought or speech.

We see a report by HN85 Roger Pearce ‘Roger Thorley’ of 4 October 1983 [UCPI019565], about a meeting attended by about 25 people. It refers to ‘bulky impassioned feminists’, a term which Pearce has agreed (when he gave evidence) was inappropriate.

Couch agrees there is no justification for the use of this term, and also that it was not challenged. He accepts it is indicative of the unit’s attitude towards women.

Looking at it now, Couch says, Roger Pearce

‘tended to put some sort of humour into his reports.’

Realising his implication, he backpedals and says that he wouldn’t have found this phrase amusing, even back then.

Again, they say they didn’t make bigoted jokes among themselves and none of them would have found it funny. Yet, for some reason, numerous officers thought it appropriate to put such content into official reports. They’re lying to us.

Turning to other irrelevant reporting, Couch says he could remember spycops reporting on the women’s peace movement. He says he wasn’t told the justification for reporting on Greenham Common camp, and never questioned the relevance.

As for spycops reporting on MPs and other elected officials, Couch claims he never saw any of it and reckons he would have raised it if he had, as it would have affected vetting.

MONEY MONEY MONEY

Even though he became the unit’s ‘finance sergeant’, dealing with the spycops expenses, Couch says he never had anything to do with overtime payments. He explains that this was always authorised by the managers.

He’s said in his statement that this extra pay was a ‘significant component’ in how much the spycops took home financially. He knew this because spycops openly discussed how overtime was a huge part of the job.

There was a cap, which they were expected to stay within. If they wanted to claim any more than this, they had to provide a good reason to the managers.

According to the SDS Annual Report of 1986, due to changes across Special Branch, the average overtime paid to undercover officers was reduced from 160 hours a month to 120 hours. Couch says that, although this affected the spycops’ morale, there was a ‘general degree of willingness’.

Couch says he never had any concerns about how much the spycops were being paid:

‘they were doing a very dangerous and very difficult job and they deserved everything they got’

He didn’t specify what any of these dangers might be.

He noted all their expenses claims in a book, after the first meeting of the week, and these were signed off by one of the managers. He then submitted this to the police finance department, and distributed the cash to the spycops at the Thursday meetings.

They would supply receipts for things like petrol, or vehicle repairs. However, for lots of other items, such as publications and subscriptions, it would have been very difficult to provide any proof, and they were taken on trust.

It would have been very difficult to know if a spycops officer was claiming for something they shouldn’t have been. But Couch says he never had any suspicions of false claims. At the end of the financial year, a senior officer from the finance department would come and check the books, and he never said there were any issues.

A LIFE OF CRIME

Couch describes how he and the spycops managers sometimes travelled outside of London to act as ‘cover officers’ for undercovers who were engaged in activities like hunt sabbing.

Couch says ‘the main reason’ for this was in case any of the spycops were arrested. He claims he doesn’t recall any instances of ever having to deal with such problems though.

In another claim of blanket ignorance that strains credulity, Couch says he’s not aware of any spycops committing any criminal offences in their undercover identities.

We were shown a report of 14 September 1984 about the arrest of the SDS officer HN19 ‘Malcolm Shearing’ [MPS-0526786]. Couch claims not to remember the report, but accepts it probably came across his desk.

At the top of the report there is a handwritten note: ‘place a copy on the arrests file’. It’s signed by squad manager HN115 Tony Wait. As we’ve been told in previous hearings, there was apparently an SDS file logging officers’ arrests. Asked if the note was directed to him, Couch claims not to recall. He also claims not to recall the arrest file’s existence.

He’s also said in his statement that he’s not aware of any spycops appearing in court as either a defendant or a witness. This is despite the fact that during his time in the squad, HN10 Bob Lambert and HN12 ‘Mike Hartley’ were not only arrested but charged and convicted under their false identities.

HN19 ‘Malcolm Shearing’, in his written statement to the Inquiry, says he reported seeing someone throw a brick at a coach being used by a far-right group. He named them in his report. His statement claimed that Couch told him the name had been edited out (because the SDS office was careful to ensure that none of the spycops was asked to appear as a witness in court, in case this risked their cover).

Couch says this editing must have been done by one of the managers and claims not to remember saying this to Shearing.

NO CARE FOR ERRANT OFFICERS

Couch has said in his statement that there should have been more processes in place to protect the welfare of the spycops, because of the ‘prolonged time’ they were being asked to stay undercover.

‘You can never get too much care when you’re doing a difficult job that they were doing, and so any more assistance they could be given should’ve been considered…

‘It was a different world, I suppose, then. You just get on with it. There wasn’t the huge backup that they’ve got these days.’

HN12 ‘Mike Hartley’ has said in his statement that he had ‘a nervous breakdown and drink-related health problem’ due to the stresses of his deployment. Couch says Hartley never spoke to him about these issues, and ‘it wasn’t obvious’.

However, we next see a report that Hartley filed in September 1984 [MPS-0726910], making it clear that members of his target group had suspicions that he was a police informer.

‘It was considered that I drank too much, as other members had smelled alcohol on my breath when I arrived for meetings. Since I am employed as a van driver, they felt that this made me liable to blackmail or coercion by the police.’

Couch says he can’t recollect this at all.

The squad’s manager HN115 Tony Wait responded to Hartley’s predicament with a memo reporting:

‘He is in need of support and this is being provided by meeting with individual SDS officers mainly from the office, on a daily basis.’

Given that Couch was one of two people doing most of the office work, he is asked if ‘individual SDS officers mainly from the office’ refers to him and HN45 ‘David Robertson’. He says he’s certain it doesn’t.

Pushed further on the Hartley problem, Couch keeps saying he can’t recall. He then comes out with:

‘I knew he had problems.’

This contradicts what he said a couple of minutes earlier.

LAMBERT AND THE INCENDIARY DEVICES

Finally, we move on to talk about ‘Operation Sparkler’, the police investigation into the role Lambert played in the 1987 incendiary device campaign that targeted Debenhams.

Couch left the SDS in July 1987, he thinks shortly before the incendiary devices were planted.

Lambert had spent a longer-than-usual period of time in the back office before deployment.

‘I thought he was a decent guy, a good cop and quite a successful undercover officer.’

He agrees that Lambert was sociable and charismatic, and says he was popular.

Couch told the Operation Sparkler investigators that he was friendly with Lambert, ‘but not socially’, and that he was a ‘productive’ officer, in terms of both the quality and quantity of reports he submitted. He is asked how the SDS assessed the quality of reports, and says he can’t remember them ever doing this; however, he does remember Lambert being thanked a lot for his ‘very useful’ work.

Couch claims not to recollect any details of the intelligence Lambert was supplying in 1987. He doesn’t recall any changes in the frequency or volume of reports, phone calls or meetings with the managers.

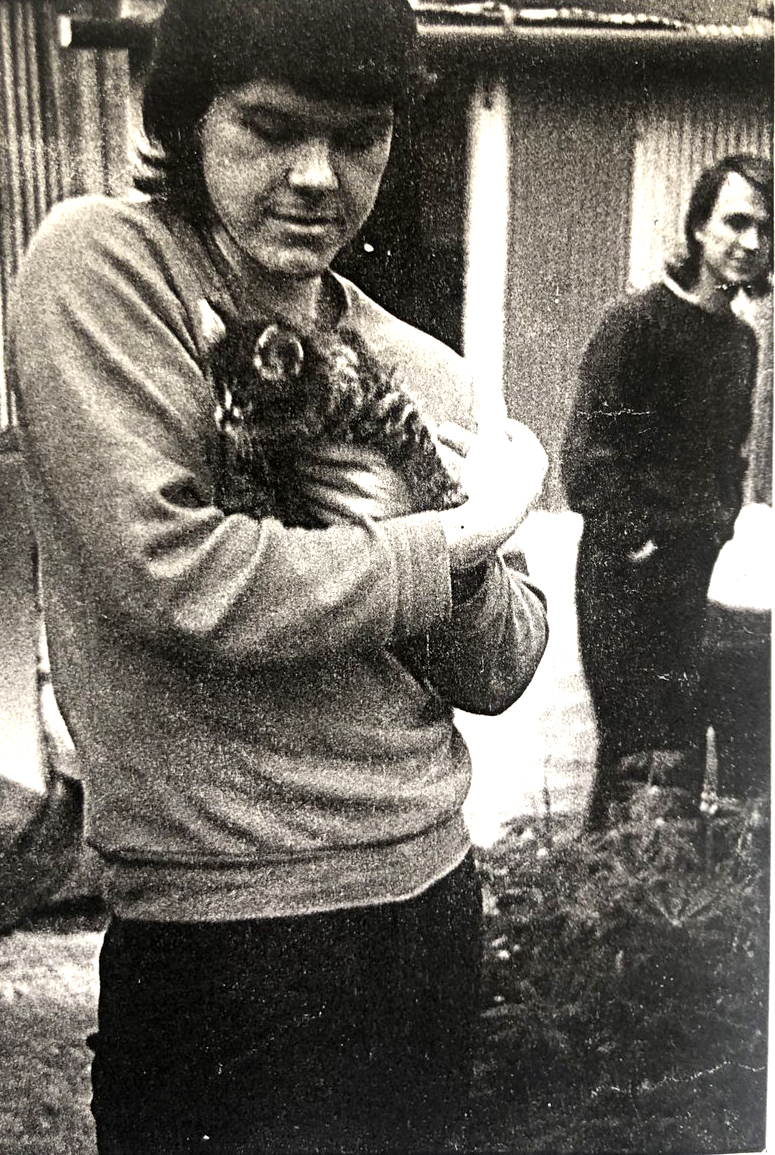

The grave of Mark Robert Robinson, who died aged 7 of a heart defect, and whose identity was stolen by spycop HN10 Bob Lambert.

This too is odd, because the records have a sudden absence immediately prior to Lambert’s Animal Liberation Front cell planting incendiary devices. Either Lambert made no reports for over a month and somehow nobody noticed or minded, or else he made reports that have since gone missing.

By September 1987, Couch was working in Special Branch’s E Squad, and spent a period of time working with the Anti-Terrorist Branch (ATB) – a branch he’d worked in before his time in the SDS.

His role in 1987 entailed liaison between ATB and Special Branch. He was asked by SDS manager HN39 Eric Docker to accompany the officers who were sent to conduct a search of Lambert’s cover flat, supposedly ‘for welfare reasons’ which were never fully explained.

This ‘search’ was organised purely to protect Lambert’s cover. It was done around the same time as searches of the home addresses of various activists on whom Lambert was reporting.

Couch concedes it’s likely that Docker mentioned the incendiary attacks to him before this search.

Couch says that all of the officers involved in this search were aware that ‘Bob Robinson’ was in fact an undercover police officer, and this was a ‘fake search’. Although Lambert was there when they knocked on the door, he didn’t answer, so they broke the door down.

Despite this being planned, he recalls that Lambert looked ‘intimidated’.

‘He looked to me to be in shock; whether he was or not I don’t know’

Lambert remained silent while his bedsit was searched.

Asked if he considered taking steps of any kind, bearing in mind that said he was there as a ‘welfare officer’, Couch claims he didn’t actually interact with Lambert at all.

‘I didn’t exchange any words with him.’

If this is true then it’s still unclear why he was there in the first place.

He confirms that the search was a ‘cursory’ one, done in order to make the entire thing look convincing if anyone from Lambert’s target group turned up. He insists that there was no operational security risk at all in him, as someone known to Lambert, being present.

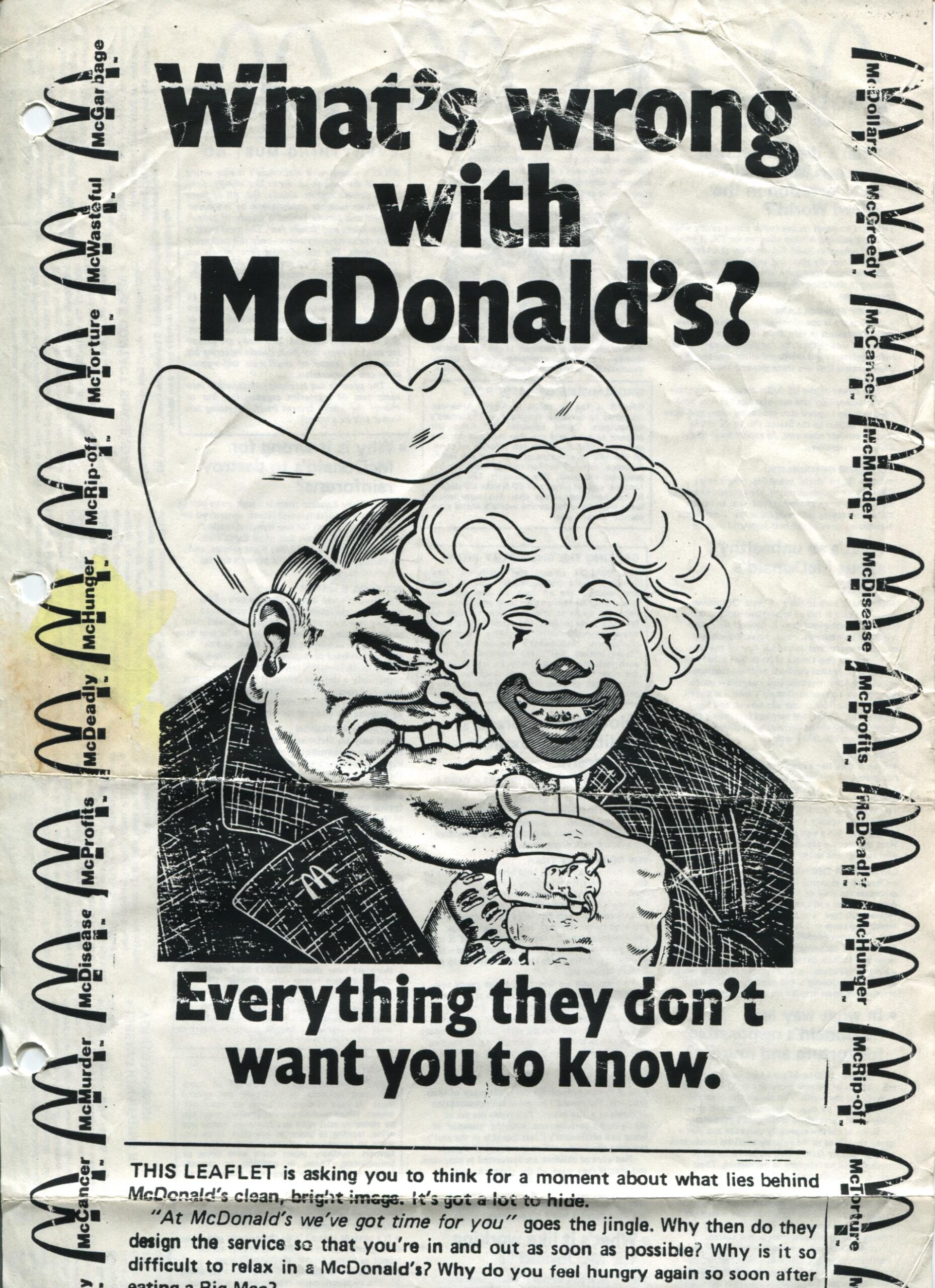

Spycop Bob Lambert and Belinda Harvey

According to notes from the interview that Operation Sparkler carried out with SDS manager HN39 Eric Docker, there were cigarettes in the flat similar to those used to construct the incendiary devices. Couch said he doesn’t remember anything about that.

Bob Lambert says that during the raid Couch picked up the photograph of Lambert and Belinda Harvey, a woman he had deceived into an intense relationship at the time. Couch firmly denies it with an absolute certainty that stands out among the wash of ignorance and fuzzy memory of the rest his questioning. If he didn’t deny this, it would fatally undermine his earlier claim that he had no idea such relationships were going on.

Michael Couch. Another spycop, another implausibly selective memory, but we nonetheless gained some significant insight into the SDS at the hearing, both overtly and between the lines.