UCPI – Weekly Report 15: 11-15 November 2024

Tranche 2, Phase 2, Week 4

11-15 November 2024

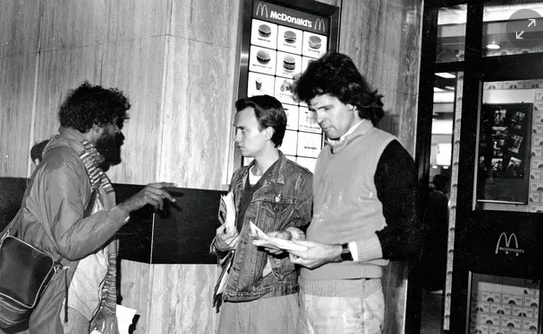

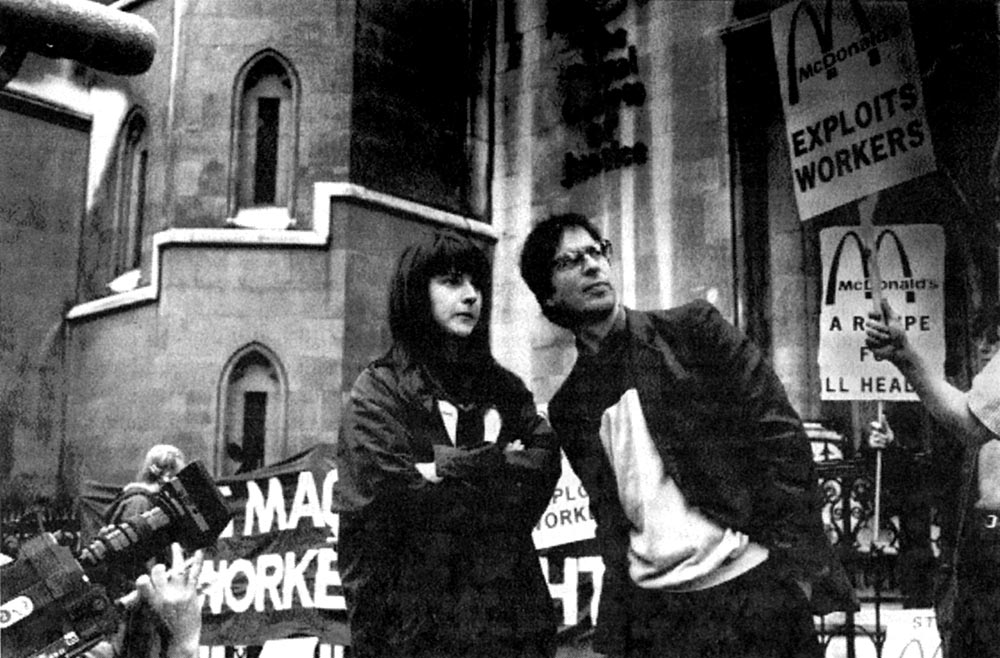

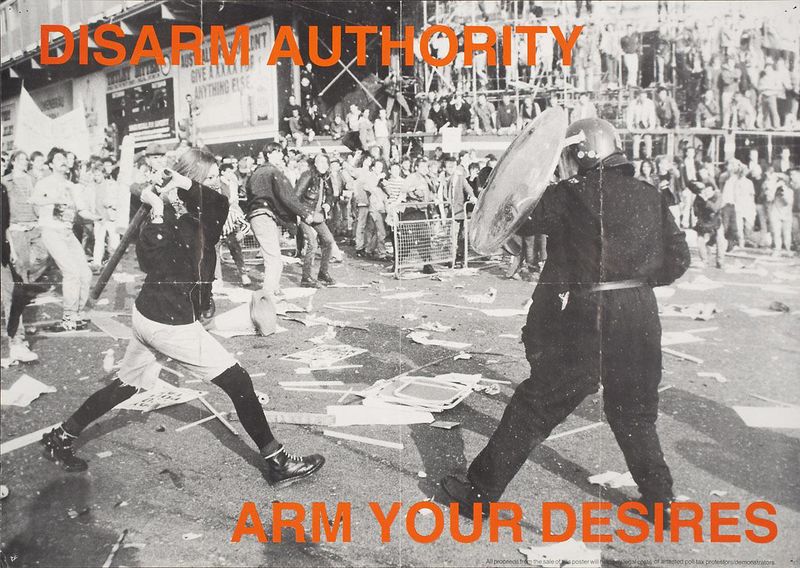

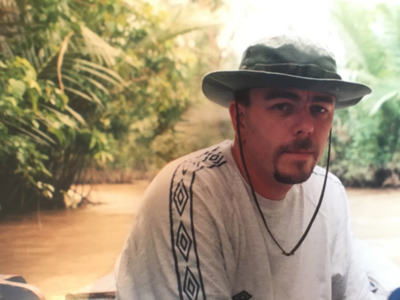

Paul Gravett (centre) & spycop HN10 Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’ (right) handing out the McLibel leaflet Lambert co-wrote, McDonald’s Oxford St, London, 1986

This summary covers the fourth week of ‘Tranche 2 Phase 2’, the new round of hearings of the Undercover Policing Inquiry (UCPI). This Phase mainly concentrates on examining the animal rights-focused activities of the Metropolitan Police’s secret political unit, the Special Demonstration Squad, from 1983-92.

The UCPI is an independent, judge-led inquiry into undercover policing in England and Wales. Its main focus is the activity of two units who deployed long-term undercover officers into a variety of political groups; the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS, 1968-2008) and the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU, 1999-2011). Spycops from these units lived as activists for years at a time, spying on more than 1,000 groups.

INTRODUCTION

It was the second of (at least) four consecutive weeks without livestreaming. This chaotic and last-minute decision by the Inquiry is because the hearings are covered by multiple Reporting Restriction Orders over private information about civilians named in the evidence (generally understood to be people who don’t want spycops’ lies about them in the public domain).

Reporting restrictions have been known to change at short notice and people reporting live from the hearings have had to delete tweets that the Inquiry considers to be in breach, so we have to err on the side of caution when writing these reports.

The Inquiry does not publish the statements, police reports, photos and other documents its refers to in questioning until after the hearing, further impeding the understanding of those of us watching. It is a public inquiry that actively excludes the public.

In the run-up to hearing evidence from HN10 Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’ at the start of December, the Inquiry is focusing on testimony from activists he spied on, largely those involved with London Greenpeace in the mid 1980s.

Other officers were committing similar abuses at the time as Lambert, such as HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’ who’s given a written statement but refused to be questioned, and HN2 Andy Coles ‘Andy Davey’ who we’ll hear from in mid December.

CONTENTS

Monday 11 November 2024

Evidence of Timothy Greene

Click here for video, transcripts and written evidence

Timothy Charles Greene was a solicitor during the period the Inquiry is now examining (1983-1992), and worked as such for 38 years. He is now a Circuit Judge. Perhaps in deference to his status in the legal profession, he was questioned by the Inquiry’s lead barrister, David Barr KC.

This hearing was not livestreamed, and at time of writing (a week after the evidence was heard), despite promises from the Inquiry neither video nor transcripts have been published on the Inquiry website, so this summary is being prepared from notes.

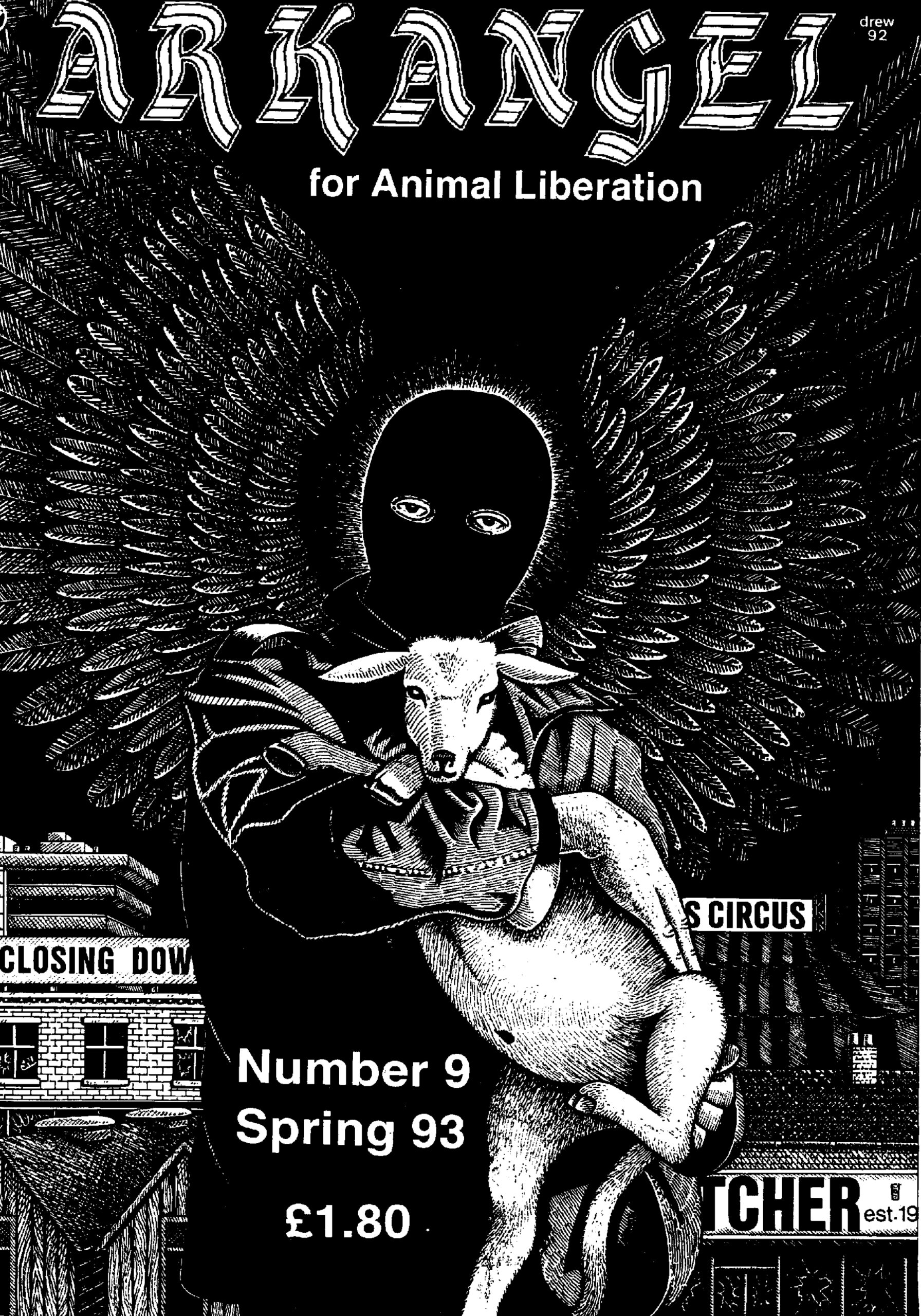

The cover of Arkangel issue 9, spring 1993

Greene’s written statement was introduced into the evidence. Neither the written statement not any of the underlying documents examined during this hearing have been published by the Inquiry yet.

Greene was asked about his career and he explained that he always had sympathy for rebels and underdogs, and he became a criminal defence lawyer.

In the 1980s he was an associate solicitor with a few years of experience often acting for activists including animal rights campaigners. He worked for Birnberg Peirce (one of the firms now representing core participants in the Inquiry) and he explained that even then the firm had a huge reputation. They didn’t have to do marketing. Clients sought them out.

He was asked about his own views, and the fact that the firm had a subscription to the animal rights magazine Arkangel. He says he would refer to it to see what his clients were up to, and that he was a vegetarian, but not a vegan.

Greene was clearly a very committed defence solicitor, who worked antisocial hours and gave clients his home number, because arrests don’t always happen during office hours.

It was clear from Barr’s questions that ‘intelligence’ from the time included multiple reports about then-solicitor Greene (and that they couldn’t even spell his name).

We saw yet more examples of the Inquiry’s chaotic, fire-fighting approach to people’s privacy, including an embarrassing incident when David Barr selected a paragraph of a document, only to find it had been redacted since he last looked.

Reports attributed to both HN10 Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’ and HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’ named Greene, although he has no memory of ever meeting either man in their undercover roles. One report called Greene an ‘oddball’ and alleged he had cemented firm friendships with some of his clients. Asked if this was true, Tim quipped ‘if I’m an oddball?’ to much laughter from the public gallery.

Much of the evidence is covered by Reporting Restriction Orders, so it is not possible to go into many of the details, however, it was clear that the reports contained many shocking lies about Greene and the animal rights activists he represented.

It was evident that Greene had a Special Branch file opened on him. He said he was not surprised, given who his clients had been. Nevertheless he was shocked and concerned that such inaccurate and blatantly untrue information was being recorded and even spread to other agencies.

Some reports were marked ‘Box 500’, which means that they were passed to MI5. We were also shown a Special Branch memo stating that a senior Detective Chief Inspector was going to personally brief the Anti-Terrorism Branch about Timothy Greene.

Another deeply concerning aspect of the reporting was the fact that privileged communications between a client and their legal representative were reported on by undercover police. There were numerous examples of this in relation to criminal proceedings, and the example of the McLibel case also came up.

Greene remembers attending a couple of meetings between the defendants and their lawyer Kier Starmer, and says he would have been shocked and deeply concerned to know that the state was involved in a civil dispute.

There were no further questions for Greene from other lawyers, but after Barr finished his questioning the room was cleared and there was a short additional hearing where he gave evidence behind closed doors.

Monday 11 November 2024

Evidence of Albert Beale

Click here for video, transcripts and written evidence

Housmans bookshop at 5 Caledonian Road, London, was home to the offices of London Greenpeace & other campaign groups

The afternoon session on 11 November saw lifelong pacifist activist, Albert Beale, being questioned by Joseph Hudson. Beale has made a written witness statement which was introduced into the evidence.

Beale primarily gave evidence about the infiltration of London Greenpeace (LGP). He is one of several witnesses being questioned about the group, which may be the most infiltrated of any small campaign group, having been targeted not only by undercover police officers but also by a succession of corporate spies working for McDonald’s.

London Greenpeace was a small organisation (wholly separate from Greenpeace International). It was concerned with a wide range of environmental and social justice issues, opposing greedy exploitation of people, animals and resources. An open public group with no formal membership, it held weekly meetings, usually attended by 5-25 people.

Before becoming active active with London Greenpeace, Beale was active in anti-militarism, anti-apartheid, feminism, gay rights and atheism, mostly in Brighton.

He spoke in detail about the War Resisters’ International (WRI) network, which is made up of numerous organisations around the world that resist war. He also gave a short history of the publication Peace News, reaching back to the 1930s.

WRI and Peace News were ideological neighbours as well as physical neighbours (they had offices in adjacent buildings) and there was always a crossover of personnel in the campaigns. London Greenpeace was formed in the 1970s by people involved in both groups, and it was launched with an article published in Peace News.

Asked about the general priorities of London Greenpeace during its early years, Beale replied that it was mainly selling a broadsheet publication. The first significant issue it addressed was opposing nuclear tests.

Beale was not hugely involved in LGP in the 1980s but he always went to meetings if he was around. He highlighted the difference between LGP and Greenpeace International:

‘Imperial Greenpeace as I still find it hard not to still call them.’

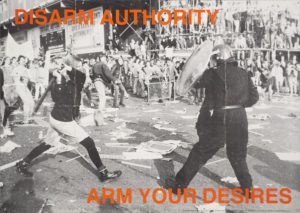

Beale was asked about whether LGP had an ‘anarchist ethos’. He responded with a clear account of anarchism as a common-sense approach:

‘If you define anarchism as a thing where people voluntarily organise themselves together, then it did have an anarchist ethos in the sense that nobody was telling it what to do. The group came together and we set our own criteria… self-activity and self-decision making on a voluntary basis… is in a sense one definition of anarchism…

‘unfortunately, of course, anarchism – as with many political philosophies where the people who adhere to it want to change the world – is seen very pejoratively. It is quite clear from seeing some of the police reports that they are using anarchism as… a term of abuse. And anarchism as I understand it is highly responsible and highly self-aware…

‘Unfortunately the cloak and dagger bomb throwing image of anarchists that you see in cartoons is all very witty but it doesn’t really have much to do with what anarchism as most of us understand it is all about.’

SO, WAS LONDON GREENPEACE A FRONT FOR THE ALF?

The main drive of Hudson’s questioning, and indeed a recurring theme throughout the past two weeks of evidence hearings, can be summed up as: You were part of London Greenpeace, but… wasn’t it really the Animal Liberation Front (ALF)?

Like all the LGP witnesses before him, Beale very clearly and repeatedly replied ‘no’.

LGP had a very broad range of interests, because of ‘the way the group worked that people with a particular interest might come and inspire others’.

Some people in the group were interested in animal rights, many were not. Within LGP, people’s interests changed over the years and the focus of the group was constantly shifting. There was nothing special about animal rights in that respect. The group always held meetings publicly and anyone could come.

The group was always a mix of generations:

‘It had old codgers and young students in it’.

Beale recognises the popularity animal rights enjoyed among younger people in the 1980s. Asked what he understands by the phrase ‘an ALF activist’, Beale said was someone who has a more radical take on the rights of animals and was in tune with the sort of things the ALF was doing. He confessed to having little understanding of the ALF. Animal issues were not something Beale was very interested in ‘because you can’t do everything’.

In fact, spycop Bob Lambert was one of the people most interested in animal liberation within the group.

Beale recalled that ‘Bob Robinson’ started attending campaign meetings in the 1980s. He was enthusiastic and quickly got involved in activities. He was friendly, willing to write leaflets and he talked about animal liberation issues from the very beginning. His appearance in the group coincided with an increased interest in animal rights.

Beale himself had criticisms of the ALF, and there were concerns within the group. Beale’s LGP comrade Martyn Lowe, who gave evidence a week earlier, is recorded in Lambert’s reporting as raising concerns about the direction LGP was taking.

Beale was sympathetic with Lowe’s position. However, he takes issue with the way those concerns were reported by Lambert, and notes that the issue was not as divisive as the reporting implies. This exaggeration of divisions within a group is a bit of a theme in SDS reporting.

Hudson asked Beale about some of the evidence the Inquiry has of LGP interest in animal rights. Much was made of an ALF leaflet stapled to an LGP newsletter. We were also shown an intelligence report from 13 December 1985 about a public event. The report claims it was addressed by ‘ALF activist’ Steve Boulding, and that most attendees were ALF activists or supporters.

Beale was clear in his answers that LGP organised public events about many different topics, including animal rights. He was directly asked if there was talk of ‘ALF-style’ property damage at London Greenpeace meetings. He says yes, those sort of things were happening at the time and so of course, they were talked about. But talking about actions that are happening is not the same as planning or orchestrating those actions.

BUILDINGS

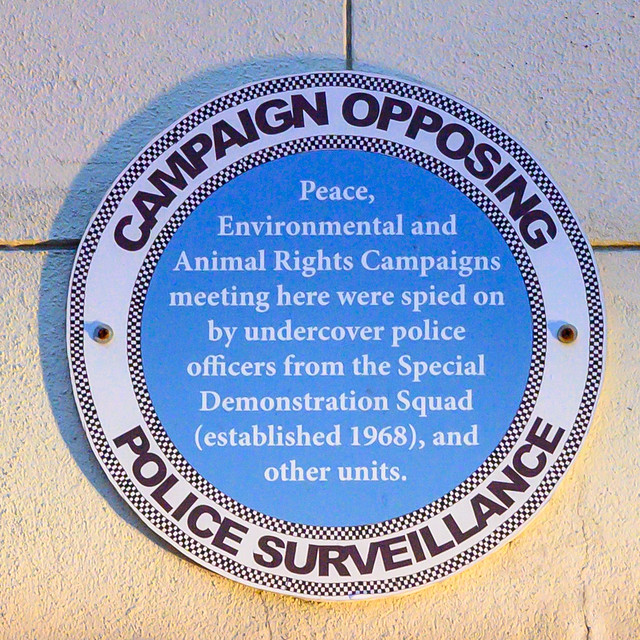

COPS blue plaque commemorating spycops’ infiltration of the shop and offices at 5 Caledonian Road, London

Hudson asked a series of rather repetitive questions about how buildings were used. Beale was asked to detail the various peace and activist groups that were based in the King’s Cross area, and how they moved around at the time.

London Greenpeace nearly always had an office in one or other of the buildings. Beale was asked about 5 Caledonian Road, which he referred to, ironically, as ‘the Peace News empire’.

The address has long been the home of Housmans bookshop, which is still based there, and it has been used by a vast number of progressive organisations over the years. It even has a COPS blue plaque commemorating the attendance of Special Demonstration Squad spies.

Beale was asked to explain how the letting out of offices was organised, which he did, listing lots of organisations that rented an office in the building over the years.

Hudson also asked about how the London Greenpeace office specifically was used. How often were people there? It was clearly run very informally.

‘I was in and out of that building anyway… There was one guy who I remember took over being one of the cheque signatories and did the sums and did that sort of thing and he popped in, from what I can remember, practically every day.’

Beale described how, in the pre-online era when print and letters were the primary method of disseminating ideas, London Greenpeace would receive huge amounts of correspondence, meaning there was always plenty of work to do responding to everyone.

The reasons for these questions appear to be that the police reporting about the offices imply they were some kind of secret organising hub. One report from 14 April 1987 claimed the ALF Supporters Group (ALFSG) was renting an office at 5 Caledonian Road, and another from 7 July 1987 suggests that London Greenpeace held ‘secret meetings’ there.

Beale batted that description away. There was no ‘secret private cabal meeting’, you have an office, and people drop in: that is not a secret meeting.

‘It is just trying to dramatise normal campaigning work, it seems to me. Of course not everybody is involved in every discussion. It’s not you are trying to make a big secret of it.

‘In fact, if you plan something at a meeting in the office when you are just with a bunch of people, presumably the next week’s normal London Greenpeace meeting presumably you would say, “Oh, we had this great idea and we have planned this and we have done this leaflet or whatever it is”…

‘I can understand, you know, if you are a police spy infiltrating a group, you have got to make the group look more furtive and more wicked to justify what you are doing…

‘the more I see of the police reports, the less serious I find I can take them, even the ones that seem plausible I now have doubts about, because some of them are so obviously absurd.’

James Wood KC took this theme further at the end, asking if Beale personally witnessed any ALF planning at London Greenpeace meetings: ‘No’.

Was there any kind of rental agreement for the ALFSG to have an office at 5 Caledonian Road? ‘No’.

Did Beale witness any planning of ALF actions in any buildings that London Greenpeace used? ‘No”.

Beale was a very good witness. His evidence really conveyed the informal nature of the organising and campaigning, and the importance of solidarity, and made it clear that the sinister way that is portrayed in the police reporting is just wrong.

He confirmed that it is perfectly plausible that ALFSG work could have been done, informally, in the LGP office, by people who were involved in both groups. Challenged by Hudson over whether, as a pacifist, he would have objected to that, Beale answered:

‘[I understand that the ALFSG] was a group whose role was to support people who were imprisoned as a result of Animal Liberation Front activities and things like that. I think there is probably a general support and solidarity with people who are facing prison for things that they have done to follow their own conscience. And one has that basic solidarity with them, even if they are doing things that you would not do yourself…

‘when people are up against the state, sometimes you just know in your gut what side you are on. You know, even if you would rather they hadn’t done it, the people who are on trial, you know where the bigger evil is…

‘It is perfectly possible as a pacifist for me to say, “Whether somebody clobbers one person or somebody drops a bomb on a thousand people, I disagree with each of those 100 per cent. Therefore I disagree with them equally”.

‘Well, yes in one logical sense I do disagree with them equally, but at the same time I can also draw a distinction between the relative demerits of some violence which is far more culpable than others. And in the world we live in, the violence of the state is the worst of all violence. That’s where so much violence in society, the mood of society, emanates from.

‘And much as I disagree with people taking violent action in support of causes, however much I think it is a good cause, I am not going to go out of my way to condemn them in the same way I will condemn the violence of the state. In fact, I may support them, not supporting their actions but supporting what’s happening to them, because they are being prosecuted.’

We were also taken to Beale’s witness statement where he talks about confidentiality being required as the element of surprise was required to make an impact.

‘It doesn’t mean that you are doing something wicked, horrible or illegal if you don’t tell people in advance.’

He explained that the state often tries to stop people doing things that are not illegal. He gave the example of distributing pacifist leaflets to military personnel.

Asked whether ‘violence’ or the tactics of the ALF were up for debate in LGP meetings, Beale replied that debates may have happened but that in his experience:

‘violence, as I define it in my statement – as harming other people, you know, physically attacking people and so on – would simply not be an option’

We were shown a section of a report subtitled ‘violence’, which claimed that someone said in a meeting that vivisectors should be ‘lined up and shot’. Beale is recorded as noting the irony of saying that in the Peace Pledge Union office.

‘it was a turn of phrase, albeit in bad taste… I am sure I would have said something about it. I might well have said something a bit stronger than “noting the irony”…

‘I have to say, some of these reports that are about things at London Greenpeace meetings and some of the ones about me are very, very clearly reports where things are being said that were said at the meeting which are reported very much in the words of the police person doing the reporting…

‘So I wouldn’t take this too literally… I wouldn’t take it as a serious proposal that anybody is sitting there saying people should be lined up and shot in a literal sense’

But, as Beale says, if you’re an undercover police officer you have to make the group you’re infiltrating sound dangerous and subversive to justify what you’re doing. We are increasingly seeing that the consequence of that is that they systematically lied in their reports.

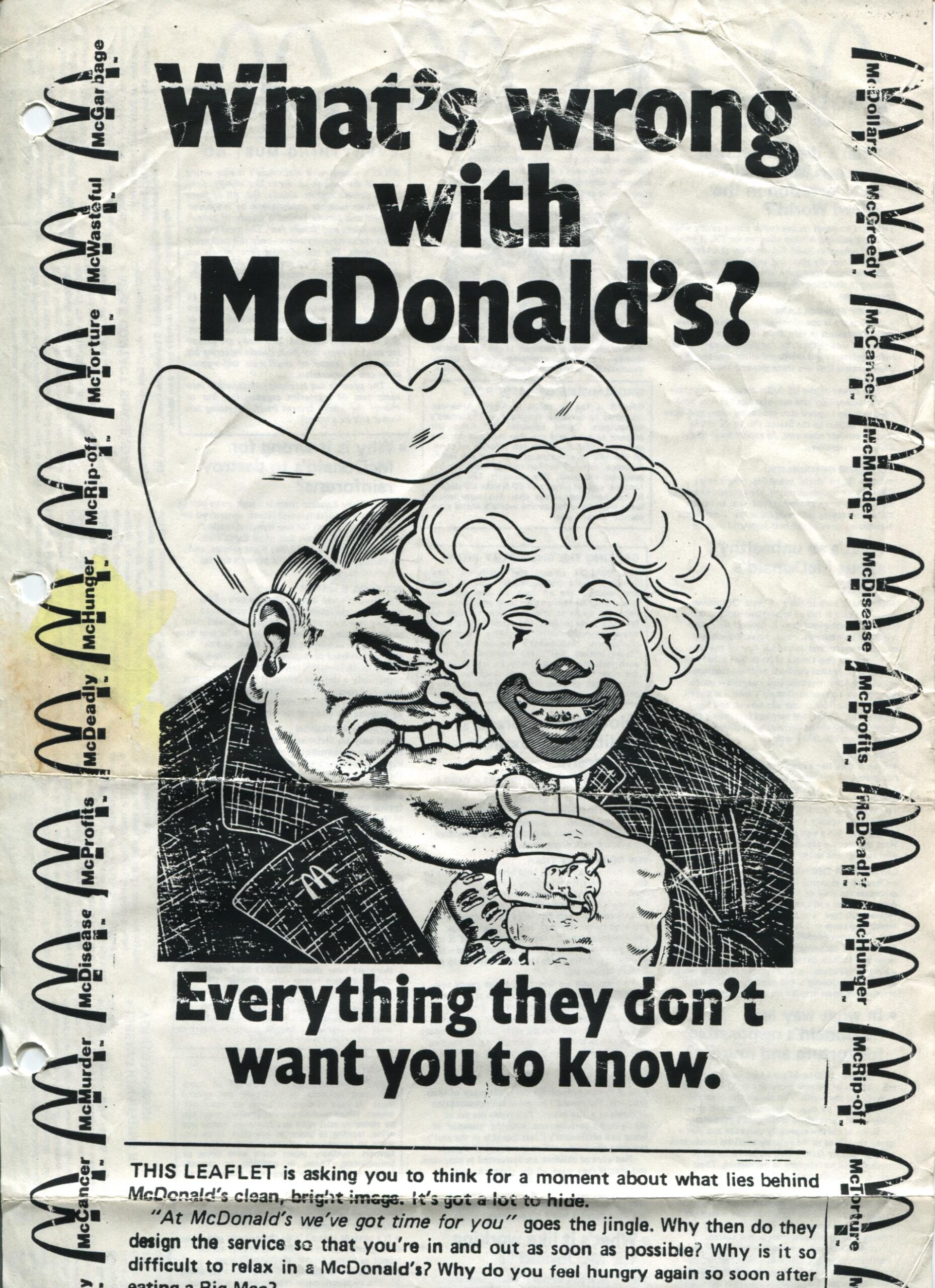

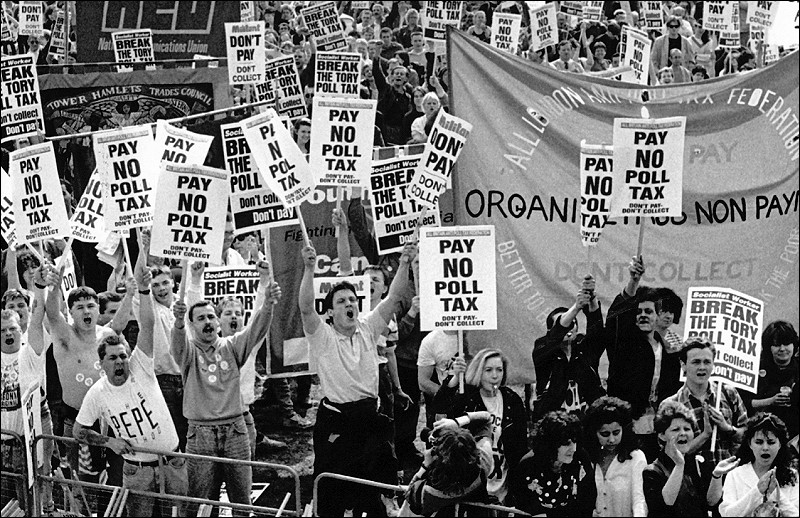

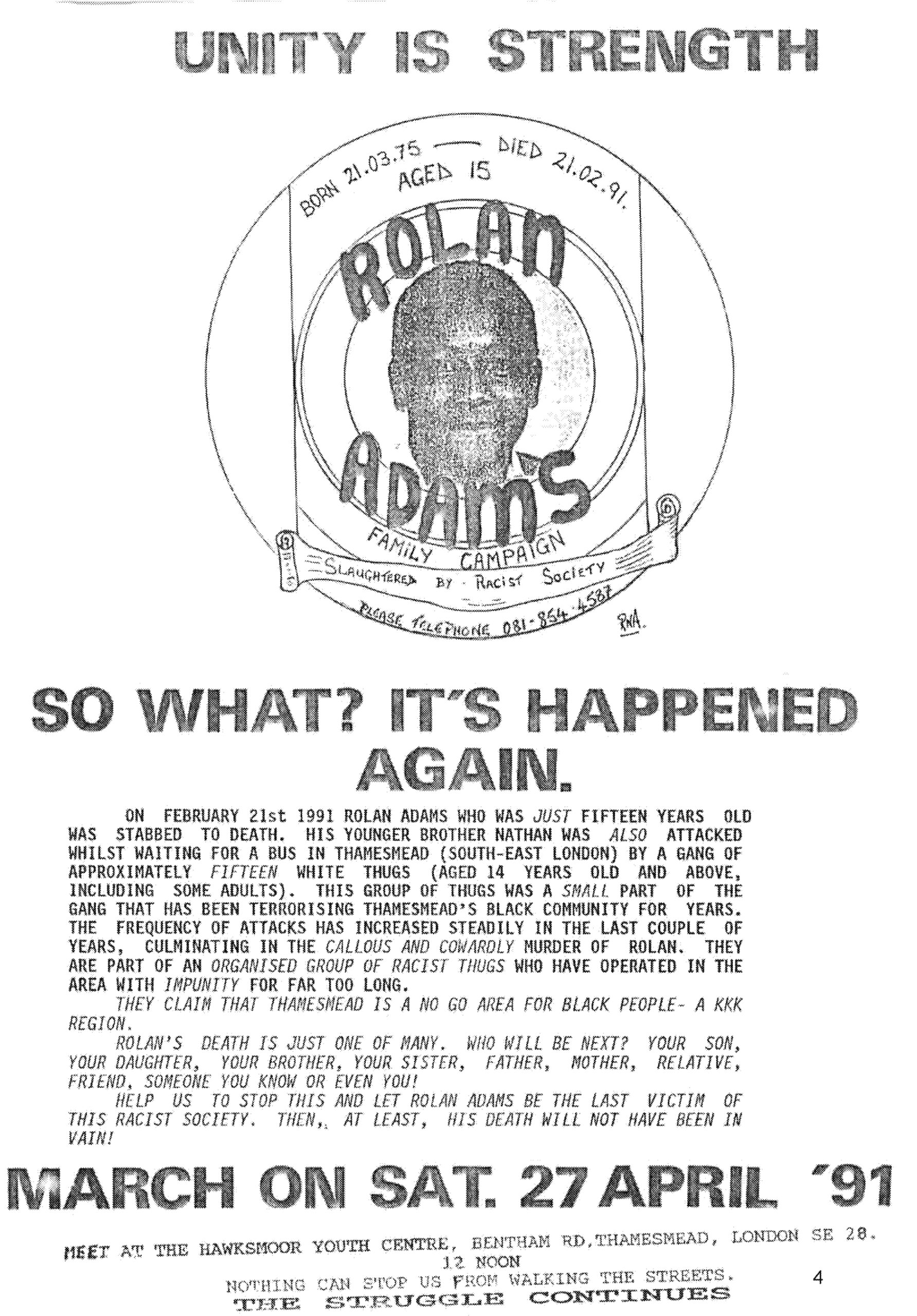

McLIBEL

Beale was also questioned about the McLibel case, when London Greenpeace produced a ‘What’s Wrong With McDonald’s?’ leaflet and were sued by the fast-food giant. Defended by LGP activists Dave Morris and Helen Steel, t became the longest-running trial in English history. The involvement of Special Demonstration Squad officers was not disclosed to the court.

Beale was shown one of LGP’s early anti-McDonald’s leaflets, and asked who might have produced it (specifically whether Lambert was involved).

‘I certainly didn’t type it, it’s not typed well enough… it looks to me like a joint production by a number of people. Bob might or might not have been one of them. I can’t say for sure, I am afraid.’

He described how sometimes you try different campaigns and some just lift off and get a buzz. A similar leaflet they made about Unilever didn’t take off. The McDonald’s campaign ‘did seem to hit a nerve’. As a result, various versions of the flyer were made.

Regarding Lambert’s involvement in writing anti-McDonald’s leaflets, Beale recalled:

‘I think he did some of the writing of them, actually… at that stage Bob was very into the corporate things as well as animal liberation things. That was kind of the two things that he sort of livened up within the group over a period of a few years.

‘So I just have this memory of him, you know, being at a meeting with people looking at leaflet drafts and Bob scribbling away and things. You know, I can’t say what word was written by whom, but he was certainly, he was certainly involved in the McDonald’s leaflets.’

Beale also made the point that LGP became more active during the McLibel trial, and his own role increased:

‘the whole McLibel thing was such an outrage that, that my solidarity with Dave and Helen during the libel case was such that I put a lot more time and energy into things around London Greenpeace.’

Hudson went on to ask about Lambert’s successor, HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’, infiltrating the group.

Beale said he didn’t warm to him as much as Bob. He remembers him monopolising Helen Steel’s attention, which turned out to be a prelude to deceiving her into an intimate relationship.

‘I just remember sitting in a pub one evening… it was kind of all jammed up on a bench in the pub with half a dozen of us from a meeting.

‘I do remember Helen was sitting next to me on one side and every time I tried to talk to her I discovered that John Dines was sitting next to her on the other side and was kind of monopolising her attention a great deal, he was obviously, you know, kind of, anyway, he was talking to her a lot and he was focusing on her a lot.

‘And I just remember that because he was on the other side of Helen from me and I didn’t know Helen very well at that stage, and I was going to ask some things and I didn’t get a word in, you know…which is not like me… I have odd flashes of memory of him.’

This pattern of undercover cops isolating women they targeted for deceitful relationships from other social contact is something we have seen in other cases as well.

Asked whether Dines had been given trusted roles within the group, Beale made it clear that anybody who came to a London Greenpeace meeting could be involved, whether an undercover or not:

‘we were a pretty open and trusting group… if they offered to do some of the work, we would be only too pleased, for goodness’ sake. Because there were times over the years when I felt lumbered with doing most of the admin work because there was nobody else around, you know, prepared to get off their backside and do it. So you were always very grateful when somebody did the work.

‘I don’t know how much work he did. I have no idea. But certainly anybody, anybody who was at the meetings would have every opportunity to take a role in any part of the work they wanted to, pretty much, and would know what was going on and could see the bank statements and things because they would all be there. It was all very open’

The point of these questions? London Greenpeace was infiltrated by more than one SDS undercover officer, and they became very involved in the private lives of people in the group.

The questioning drew out the complete lack of any justification for such intrusiveness, with Beale confirming that there was no information he was privy to a police officer could not have gleaned by simply turning up to a meeting.

Beale concluded by reflecting on the personal impact of these infiltrations. It was heartbreaking to hear him talking about how trusting the group had been:

‘we all have to trust each other as fellow human beings and fellow campaigners. I mean clearly we were silly to do so in retrospect, but you treat people as you want them to treat you, you trust them.’

Beale made the point that some of the overt political policing he has experienced has been bad:

‘I have been on the receiving end of what you might call the political police in this country a few other times beyond London Greenpeace, which in some ways have had more of an effect on me on one level, but in terms of the emotional effect, this is the worst.

‘I mean, having people you sit in the pub with, who are your mates, turning out to do this. It is outrageous.’

Tuesday 12 November 2024

Evidence of Robin Lane

Click here for video, transcripts and written evidence

Robin Lane (left) and friend

Some of this day’s evidence is covered by Reporting Restriction Orders, which means that not everything said in the hearing room can be reported outside of it.

However, we can tell you that Robin Lane has provided an 83 page written statement and some exhibits to the Inquiry. If we’re lucky, these will eventually appear on the ‘Day 12’ page of the UCPI website, but please do not hold your breath.

Questions were asked by one of the Inquiry’s Junior Counsel, Rachel Naylor.

Lane has dedicated most of his life to campaigning for animal rights. He has been vegan for over 40 years, and his main focus in recent years has been the promotion of veganism.

He first became politically active in 1980, joining the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND). He became a local contact for the British Union Against Vivisection, now called Cruelty Free International, in late 1982.

He was involved in a number of animal rights groups. After the South London Animal Movement (SLAM) and ‘RATS’, he took up the role of press officer with the Animal Liberation Front Supporters Group (ALFSG) in 1986. He served some time in prison, and after his release, set up a new Campaign Against Leather & Fur (CALF) in 1989. In the 90s he was involved in setting up the Animal Rights Coalition London and London Animal Action (LAA).

NON-VIOLENCE

Lane was shown a leaflet from 1983 – attached to a police report [UCPI020446] – which described different forms of Civil Disobedience (referred to as CD). These included such tactics as occupying zebra crossings by walking over them continuously. According to the leaflet: ‘Non violent CD is very important’.

Lane was asked for his thoughts about this, and exactly which forms of non-violent direct action he considered legitimate and acceptable. It is unclear why the available transcript has been so heavily redacted, as nothing he said during the missing 25 minutes contravened any of the Inquiry’s Reporting Restriction Orders.

It was obvious to everyone that Lane was opposed to violence, and cared deeply about the horrific treatment of animals. He doesn’t agree with taking direct action against personal property, homes and cars, but considers it legitimate to protest outside businesses and sites of animal suffering, or to damage items that are used to torture animals.

He felt the actions taken by him and others were ‘perfectly reasonable’, and people could choose to risk arrest if they wanted to. He preferred demonstrations that did not attract a (potentially violent) police presence.

It was evident that he had spent a lot of time thinking about what constituted non-violent direct action. Indiscriminate or ill-planned actions that might lead to other people (especially children) being adversely affected, were not acceptable to him. He made it very clear that he did not support certain types of action.

SOUTH LONDON ANIMAL MOVEMENT (SLAM)

It seems likely that Robin Lane’s name was first recorded by Special Branch when he attended the first meeting of the reincarnated South London Animal Movement (SLAM) in 1983.

He recalls SLAM as a very ‘democratic’, open and law-abiding group. It was non-hierarchical – everyone sat in a circle, and there was nobody in charge – and ‘easy-going’.

He says someone called ‘Mike Blake’ turned up, and became part of the group. This was in fact an SDS officer, HN11 Mike Chitty, whose first report about SLAM [UCPI019336] described Lane as a ‘self-confessed anarchist’. He denies this, and says he was never an anarchist, has always voted in elections, and goes on to talk about the prevalence of punk at the time:

‘a lot of people called themselves anarchists. I don’t ever think they were really anarchists’.

According to Chitty’s secret police reports, there was lots of discussion of ALF-style actions, such as criminal damage, at the group’s meetings, and SLAM would soon start claiming responsibility for such actions in order to ‘put itself on the map’.

It seems improbable that anyone would have discussed this kind of illegal activity at a meeting which was completely open to the public.

Lane was asked if SLAM was in fact a conduit used to recruit people into the Animal Liberation Front (ALF). He tried to get an important point across to the Inquiry – that ‘ALF’ is an action, taken by an individual, not the name of an organisation:

‘There is no “the ALF”.’

In March 1984, there was an ALF raid on the Institute of Psychiatry (IoP) in Camberwell, resulting in the liberation of rats that were being experimented on there. Members of SLAM heard about this on the news, and realised that there was vivisection happening in their local area.

They set up a working party to discuss campaigning about this, and a ‘handful’ of interested people met at Lane’s home to talk about their ideas. They organised a demo, which took place in January 1985.

Over 1000 people marched from the Institute all the way to Parliament, held a minute’s silence for the animals, then returned to Denmark Hill in Camberwell, where a large group blocked the traffic.

We saw a photograph [UCPI037136] of this march. It was openly organised, planned with the police, who complimented them on their stewarding, and the relevant local councils. This was the first march Lane had ever organised, and he considered it ‘a great success’.

Dr Brian Meldrum

The group learnt more about one particular vivisector based at the IoP, who conducted tests on baboons and mice, Dr Brian Meldrum. They decided to focus their campaigning on him.

Why focus on an individual rather than the entire institution? The working party did lots of research – he recalls ‘trawling through microfiches’ – and this made them realise the sheer size of the Institute and its experiments. They thought that unwieldy scale meant it made sense to focus on one main scientist and then make the links.

According to another Special Demonstration Squad report [UCPI014770], the group produced leaflets that included a photo of Meldrum and described the kind of experiments he was conducting. SLAM planned to distribute these locally, around the IoP and around Meldrum’s house.

Lane recalls that they’d originally thought about including Meldrum’s home address on it, but decided not to. The report suggested that there was much more disquiet about this campaign within SLAM than Lane remembers, and referred to it as a ’hate campaign’. He says it wasn’t; it was a campaign against vivisection – ‘against the torture, you know, of baboons and mice’.

The group used street theatre to raise public awareness of Meldrum’s controversial experiments (for example those where he used strobe lights to cause the baboons to have epileptic seizures), and sometimes held demonstrations outside his house.

We saw some photographs of this. In one [UCPI037134], a SLAM member is wearing a baboon suit. Lane is pictured shining a torch towards their face, and a local bobby stands watching. Another photo [UCPI037137] shows Lane wearing his Meldrum costume, a stained lab coat.

Attached to another report from spycops Mike Chitty [UCPI021972] is a four-page article written by Lane, which appeared in a new publication (‘The Door’) in 1986. Entitled ‘Looking back’, it describes some of the events held outside this house by the group.

Lane recalls that what they called ‘home visits’ were normal in those days, not seen as a big deal by the police, and entirely legal. There was no criminal offence being committed.

He remembers Meldrum’s wife coming out of the house on one occasion. She wasn’t frightened or intimidated, just angry about them holding a chimps’ tea-party in the driveway on the day of her husband’s 50th birthday party.

Lane said such home visits were widely seen as a legitimate form of campaigning, but the law has changed since then and he probably wouldn’t do these now.

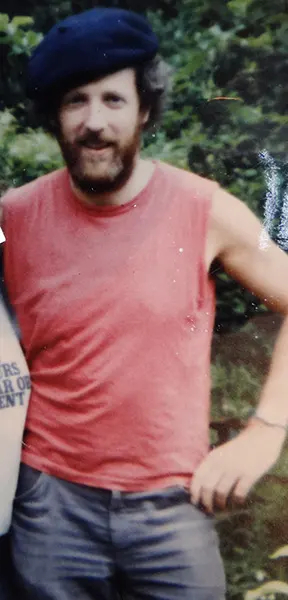

Spycop HN11 Mike Chitty ‘Mike Blake’ undercover in the 1980s

SLAM didn’t tend to advertise these demos widely or in advance, it was just members of the group who turned up. Would spycop Mike Chitty have known about them? Lane has no idea; he doesn’t remember ‘Mike Blake’ being present at any of these home visits, but points out that ‘Mike’ wasn’t around all the time; he was involved in lots of different animal rights groups.

We moved on to hear about another tactic, announced at a SLAM meeting [UCPI021972] which Lane remembers as ‘very good’. Activists made very creative use of Freepost coupons, and as a result, Meldrum received hundreds of catalogues and packages over the course of a month. This constituted ‘a very effective way’ of taking up a vivisector’s time, says Lane.

According to a Polly Toynbee article in the Guardian, around 50% of Meldrum’s time was spent dealing with the campaigning.

The Inquiry then produced an article, ‘The Armchair Activist’, taken from issue 19 of the ALF Supporters’ Group (ALFSG) magazine, attached to a police report of December 1986 [MPS 0745764]. Lane recalled that their solicitor at this time advised against publishing this article, in case it was considered ‘incitement’.

This was around the same time as a number of animal rights activists were facing conspiracy charges in Sheffield. The ALFSG was keen to avoid breaking the law, so rather than distributing the magazine as it was, or reprinting it, they physically ripped those pages out.

Excerpts from the article were read out. It described how some activists had developed the Freepost idea much further, as an easily accessible form of action that could be done by anyone with access to a phone – using it to order goods and services for those they targeted. This was said to cause ‘utter misery’ for the recipients.

Lane pointed out that what SLAM had done was completely different; they just used Freepost; they didn’t order any of these other things (such as skips, scaffolding or funeral directors) for Meldrum, or anyone else.

Lane said that he and ‘Tanya’ (his girlfriend at the time) had both been very involved in campaigning against Meldrum’s cruelty, and had always done so in a legal, above-board way.

He did not agree with more extreme forms of action taken by others, and felt very strongly about this. He considered SLAM’s campaigns to be very successful. This one generated a lot of publicity, locally and nationally. However there were some people in SLAM who didn’t like this.

RATS

He, ‘Tanya’ and two friends all left SLAM as a result, and set up their own small group, calling it RATS (not an acronym).

Their aim was to raise money for animal sanctuaries (places set up to look after various animals after they’d been rescued from labs and other places). They borrowed from the ALFSG to pay for printing their first leaflet, and later on raised funds for them as well.

The ALFSG were always fundraising (including through the sale of magazines and merchandise) so they could support animal rights prisoners. Lane drew a clear distinction between this and actual ALF actions: ‘It had to be completely separate’.

The ALFSG was an organisation, with a bank account and a membership, who made regular donations. Even his mum was a member and yet she was, as far as he knows, not involved in ALF activism!

The first police report which mentions this ‘newly formed (anarchist) animal rights group, RATS’ is dated October 1985 [UCPI021949].

Lane says he was very surprised when he saw the leaflet attached to it, which claims that RATS has been ‘set up to raise money for the Animal Liberation Front’. He does not recognise it at all, and says it definitely wasn’t made by him or the other three people involved in RATS (who were all very close friends; none of them were ‘anarchists’):

‘I wouldn’t be at all surprised if the powers that be produced this, because I certainly did not… I disassociate myself with this leaflet’.

In contrast, he does recognise the leaflet attached to a report from January 1986 [UCPI021956]. He explains that this one was put out by RATS, to inform the public what ALF was about, and to counter some of the myths and misinformation that appeared in the media about animal rights activism.

In his opinion, ALF activists were ‘amazing people’, who were doing their best to stop animals suffering, and who didn’t deserve the bad press they were getting at this time. This genuine RATS flyer is clear that they’re a ‘fund-rasing group’ who aim to raise money for both the ALFSG and animal sanctuaries.

ANIMAL LIBERATION FRONT SUPPORTERS’ GROUP (ALFSG)

Shortly after this, Lane and ‘Tanya’ both began helping Vivienne Smith at the ALFSG office in Hammersmith. One of Lane’s jobs was responding to letters that had appeared in the press about ALF activities.

Two animal liberation activists in balaclavas, each holding a rescued white rabbit

After about six months, he was asked to take on the role of press officer and, after Viv went to prison, to run the ALFSG office. He was raided by the police’s anti-terrorist squad a year later, and then stepped down from these roles before his own trial, which took place in Cardiff in the summer of 1988.

He says he was fully supportive of the ALF actions being taken, and welcomed the press officer role as an opportunity to speak out publicly about what was going on in the meat trade, the fur industry, etc. He used a pseudonym for this (having received threats from butchers, and unwelcome media intrusion at his home).

When ALF activists contacted the office, they did so completely anonymously. The job of the press officer was to provide comments to any media outlets who got in touch. In the 1980s there was a lot of ALF activity – he recalls around five actions every day – so he was kept busy.

The magazine and its printing were done by other people. There was a treasurer in Dorset who handled the finances. Lane coordinated the admin done at the office and says his was ‘pretty much a full-time job’.

We saw an example of an ALFSG ‘diary of actions’, a compilation of news about different actions that had taken place around the country over several months. This was included in a report by Bob Lambert [MPS 0744786]. He also included details of the legal advice provided to the ALFSG by their solicitor, information that should have been treated as ‘legally privileged’ by the police.

Lane says he didn’t know Bob that well, and that ‘he definitely did not’ accompany Lane and ‘Tanya’ on a visit to HMP Hull (where ALF founder Ronnie Lee was being held).

Another Lambert report [UCPI028387] purports to contain details of a conversation taking place at the prison between Lane and Lee. There are a number of reports written by Lambert which Lane doesn’t agree with:

‘I think you should take a lot of what HN10 said with a pinch of salt, you know. I think there is a lot of stuff that has made up here’

Lane does remember that the National Anti-Vivisection Society (NAVS) made a donation towards the ALFSG, but he was never the group’s treasurer and can’t be sure of its size.

However, he absolutely rejects any suggestion that money given to the ALFSG during his time there was used to fund any ALF actions or criminal activity. Besides covering the costs of printing and admin, the money was used to support activists who had been arrested and/or imprisoned.

He also repudiates the contents of another report [MPS 0742704], and its allegation that he’d made a secret agreement with Lee and another activist, known as ‘GFT’, not to publicly condemn any action carried out under the banner of the ‘Animal Rights Militia’ (ARM) including its ‘bombing campaigns’.

Lane repeated what he’d said earlier about his commitment to non-violence. He never moved away from this pacifism, and never supported any violence. He recalls being very strict as a press officer. He wouldn’t report actions that broke the ALF code, and would disown them if asked about them.

‘in my time there was no connection between ALF and ARM. Absolutely none’.

He wondered at times if ARM really did exist, and notes that its existence would have suited the authorities.

Similarly, he doesn’t recognise the claims in another report [UCPI028517] that he had been encouraging closer ties with London Greenpeace (LGP). He explained earlier that he didn’t have much involvement with LGP as it met in North London and he tended to stay active locally, in the South of the city.

After the Hammersmith office closed down, the ALFSG admin was done at his home. As with all other witnesses asked about the police’s assertion, Lane is adamant that there was no agreement to share the LGP office in Kings Cross.

He did the ALFSG admin alone, after his relationship with ‘Tanya’ ended. He denies the suggestions made in various police reports that Gabrielle Bosley, Helen Steel or ‘Bob Robinson’ were ever involved in the ALFSG. He doesn’t remember Steel having a liaison role, organising printing or attending a meeting with him, ‘Tanya’ and two other activists.

Both LGP and ‘Green Anarchist’ later reprinted the text he’d originally put together for the RATS leaflet, but he wasn’t involved in this. He points out that supporting a group is different to being part of it. Many of those in one group might be sympathetic to or supportive of the aims of another group, but there wasn’t as much crossover between LGP and ALFSG as the secret police reports imply.

He remembers Support Animal Rights Prisoners (SARP) as a ‘very prominent, very good group’. He wasn’t involved in it. SARP’s remit was much wider than the ALFSG’s: they did lots of letter-writing and campaigning around provision of vegan food and toiletries to prisoners.

HN2 Andy Coles ‘Andy Davey’ (due to give evidence in December) claimed that SARP had been set up in order to support more violent ARM prisoners who wouldn’t qualify for ALFSG support.

‘I think that is nonsense’.

BOB LAMBERT’S LIES

Equally, it is clear that Lane doesn’t believe Bob Lambert’s claims, either those made in his witness statement [UCPI 035081] or the ones which led to him receiving an official police Commissioner’s Commendation [MPS 0726999] for his undercover work.

One of these claims was that he worked ‘at the ALF office’ and monitored their ‘hierarchy’. Lane does not remember ever seeing Bob, or his van, at the ALFSG office, and points out that ‘there was no hierarchy’.

Another was that he’d had meetings with Ronnie Lee and was involved in setting up ALF prisoner support. Lane points out that there were only three or four people involved in the ALFSG, and it’s inconceivable that Lambert could have done any of these things without Lane noticing.

The claim of Lambert’s that the Inquiry spent the most time unpicking was a convoluted story which seems to have been invented to explain how he was able to learn so much about an ALF cell’s future plans, without being part of it.

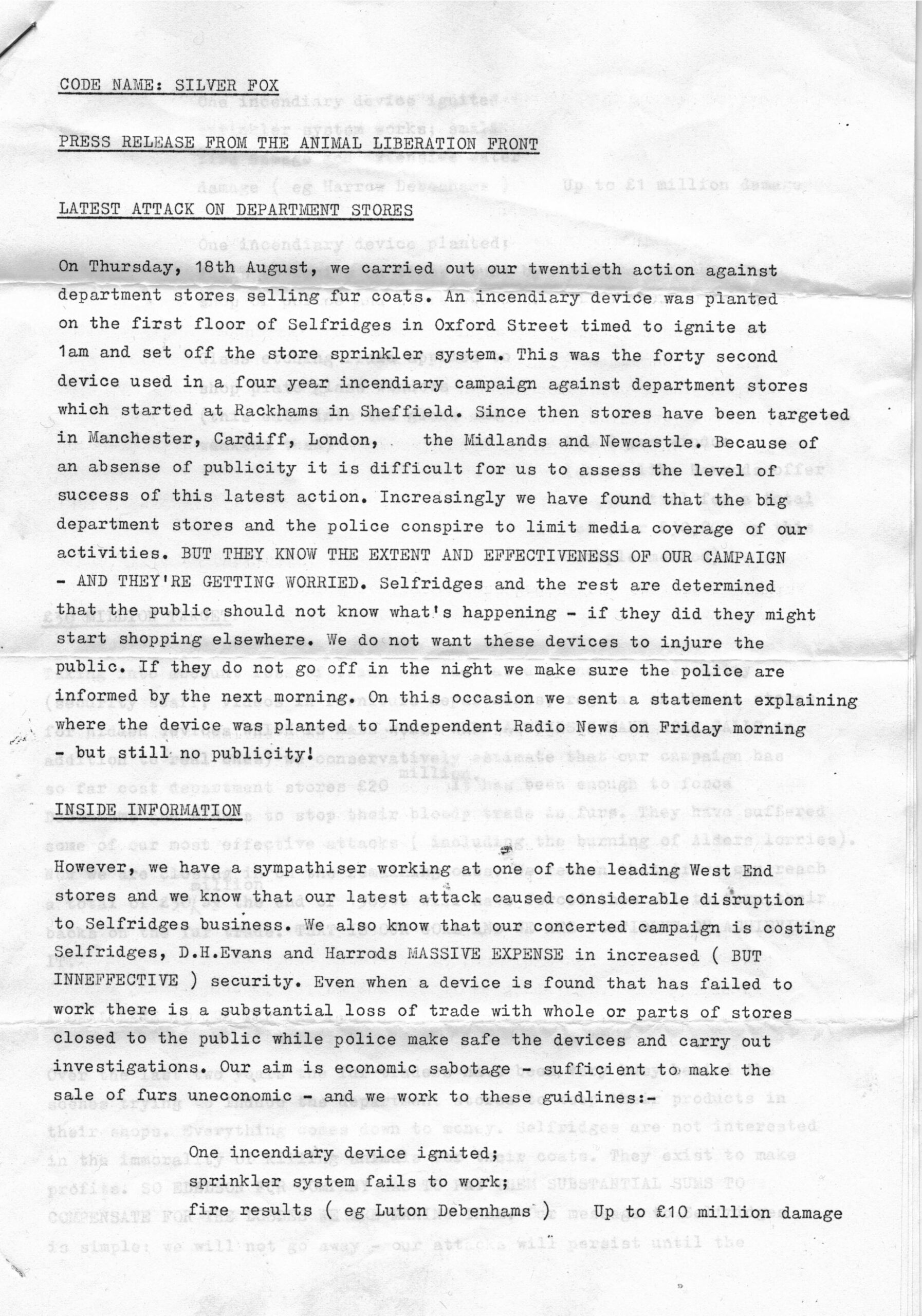

Lambert is was part of a cell that placed timed incendiary devices in branch’s of Debenham’s department store, in protest at the sale of fur. Lambert is accused of setting the device that burned down the Harrow shop.

This would have been far beyond anything he could justify to his bosses. Unsurprisingly, he denies it. However, he still needs to explain why they trusted him so much.

Lambert apparently suggested that he was going to fulfil some kind of communications role, between the cell (Geoff Sheppard and Andrew Clarke) and the wider animal rights movement, and also the media.

Supposedly they trusted him to explain why they’d adopted these tactics (the use of incendiary devices in shops) to other activists. He said that because he was going to act as some kind of ‘press officer’, they shared information with him about the next set of attacks, that they were planning to carry out in September.

As someone who actually did act as a press officer, explaining ALF actions to the media, Lane was well-placed to offer an expert opinion about this. He points out that he only ever found out about actions after they had happened.

‘I didn’t know about actions beforehand, and it would have been ridiculous for me to have known’.

The ALFSG couldn’t afford the risk of him being done for ‘conspiracy’. He says Lambert ‘must have been part of a cell’ otherwise he would not have been privy to the level of detail about future actions that he claimed.

In his statement, Lambert claimed that by late 1988, he was a ‘trusted colleague of the main Animal Liberation Front activists’ (listing Lee, Smith, Lane and others) and was being considered for a ‘more formal role’ in the ALFSG.

‘I don’t understand what he’s talking about. He was never involved in the Animal Liberation Front Supporters Group so far as I was concerned’.

He says Bob’s fantasy of being considered as his successor was ‘extremely unlikely’.

Asked if Lambert was, as he claimed, Lane’s trusted colleague, the response was unequivocal:

‘Never. In fact, in fact I was suspicious of him.’

Lane recalls a comment Lambert made in a pub after a gig in Brixton (one of the few times they ever socialised in the same place). The subject of undercover cops came up. Lane made a comment about them being the ‘scum of the earth’ and still remembers the way Lambert responded: ‘but Robin, sometimes it’s necessary’.

‘I was always suspicious of him after that’

Lambert reported that he didn’t take up a formal role in the group, but organised transport for prison visits and also for supporters to attend Lane’s trial in Cardiff. However, Lane says this isn’t true. He had some very good friends who came to his trial from London, and they all travelled by train. He doesn’t know who Bob’s talking about.

When the Debenham’s actions happened in July 1987, Lane was the ALF press officer. He had no idea who was responsible, and nobody got in touch with him to claim the attacks.

Although he had nothing to do with it, his house was searched and turned upside down in a very traumatising way, and he was arrested. He remembers giving a ‘no comment’ interview (which lasted five hours) and suffering from panic attacks afterwards. He has no idea why he was targeted.

He also has no knowledge of any internal ‘investigation’ into the possible infiltration of the ALF, something said to have been requested by Andrew Clarke. This is mentioned in a report from November 1987 [MPS 0740488].

LANE’S LEGAL CASE AND RELEASE FROM PRISON

We moved on to hear about Lane’s own trial, in June 1988. He was convicted and sentenced to 18 months’ imprisonment. He ended up serving four and a half months. This was for ‘conspiracy to incite others to commit criminal damage’.

Spycop Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’ and Belinda Harvey

The prosecution case centred on the ‘diary of actions’ that we’d seen earlier. There was no disclosure of the fact that an undercover police officer was involved in the case.

There was a party organised to celebrate him getting out of prison at the end of October. This was a small, private event, held at his barrister’s house, with food provided by the family. Only his closest friends, people who had been supporting him while he was inside, were invited.

There was only one gate-crasher: Bob Lambert. Although Robin was, in his own words, ‘slightly peeved to see him there’, he didn’t feel able to exclude him, as he’d tagged along with Belinda Harvey, his girlfriend at the time. One of the tactical advantages of deceiving trusted women into relationships was the way it allowed the officer to piggyback the woman’s social popularity.

In Lambert’s report of the event [MPS 0740647] he claimed that this weekend was a gathering of ALF activists for ‘important tactical and theoretical discussions’, but Lane says ‘this is pure fantasy’ and assures us that it was in fact ‘fun’, a ‘nice time’ and ‘nothing to do with ALF or anything like that’.

He also describes as ‘fantasy’ the bit in Lambert’s report that calls him ‘the perfect illustration of a broken man’. He says he was actually very happy and healthy at this time. He had already decided to step back from the stress of being involved in the ALFSG. He had a new relationship, and got involved in ‘Life Before Profit’ (a pacifist, environmentalist, vegan group).

ARKANGEL MAGAZINE

The cover of Arkangel issue 2, spring 1990

Lane started a new magazine, Arkangel, and ran it himself, with someone else doing the ‘desk-top publishing’ layout. There was no subscriber list, just a box of index cards, and addresses were written by hand on the envelopes. This was done by him, his new girlfriend and two other helpers (sisters who lived at the sanctuary), nobody else, and certainly not HN2 Andy Coles ‘Andy Davey’.

However, Coles attached a subscriber list to one of his reports [MPS 0739503], claiming to have compiled this by printing out address labels on the ALFSG computer.

This is a bit baffling. Robin says that the addresses were always hand-written – there weren’t any printed labels – and in any case, the ALFSG computer was never used for Arkangel.

Short of breaking into his house when he wasn’t there, and writing out or photographing these several hundred index cards, Lane can’t see how Coles would have copied the list.

Lane doesn’t remember where or when he first met Coles, but recalls ‘Andy Van’ (as he was called) offering him lifts to Animal Rights Coalition (ARC) meetings in the West Midlands, and to collect Arkangel from the printers in Northampton. He doesn’t remember what they spoke about in Andy’s van, but is clear that they weren’t friends and didn’t socialise together. After making several of these long trips to ARC meetings, Lane suggested setting up the same kind of coalition in London.

ANIMAL RIGHTS COALITION (ARC)

Coles has claimed in his witness statement that another activist, ‘EAB’, had invited him to get involved in ARC London, because of his previous involvement in the ‘South East ARC’.

However, Lane tells a different story. ‘EAB’ was a good friend of his, and he suggested inviting her along to the pair’s planning meetings (held in Andy’s bedsit). He has never heard of a ‘South East ARC’.

ARC London’s first meeting took place in February 1994. It acted as an umbrella organisation, the idea was that it would bring together all the different animal rights groups which existed at the time, to share news and discuss what they were doing.

HN2 Andy Coles offered to produce an ARC London newsletter but neither Lane nor the Inquiry seem to have any copies of it.

The Inquiry does have a pro-forma submitted by Coles that June [MPS 0745749], naming Robin Lane as the organiser (‘under the auspices of Animal Rights Collective London’) of a demo at Christie’s auction house, where a fund-raising auction was being held for the British Field Sports Society (BFSS).

It suggests that thanks to his obtaining a sale catalogue, details of BFSS donors have been circulated in the animal rights movement and they are likely to be ‘targeted’ in some way. Lane says he just picked up a free copy of the catalogue, it was quite heavy, and he had no intention of circulating copies to anyone else.

This pro-forma also mentions him organising a protest at the Serpentine Gallery. Damian Hurst’s art show featured a dead sheep in a glass case. Lane remembers it ‘like it was yesterday’. All they did was hold hands in a circle around this case, and this made visitors unhappy because they weren’t able to get close to it.

He denies there’s any truth in the next Coles’s report [UCPI0746014], about Coles and him being part of a new committee formed to organise an alternative to the National Anti-Vivisection Society (NAVS) demo held on World Day for Laboratory Animals. He says he thought that NAVS ‘were doing a good job’ and can’t see why he would have wanted to ‘radicalise’ this annual event.

In his witness statement [UCPI035074], Coles claims that setting up this ARC was ‘core to my strategy’ – it helped him identify and report on potential ALF activists – yet Lane points out that this could have been achieved by any ‘ordinary police officer’ coming along to what were entirely open, public meetings.

LONDON ANIMAL ACTION

In any case, by the end of 1994 London Animal Action (LAA) had been created, and ARC was no longer needed. This new organisation ran until 2005, and was spied on by HN2 and at least two other undercovers (HN1 ‘Matt Rayner’ and HN26 ‘Christine Green’). Its meetings were also entirely open to anyone.

The meetings were organised by a small committee, made up of Lane and just four others, and he denies that Coles was involved in this, or as ‘prominent’ as he claims:

‘I think that’s probably an exaggeration on his part’

He accepts that Coles may well have been involved in putting out ‘London Animal Rights News’, although his main memory of collating and mailing out this publication was of doing the work in the Crystal Palace flat of ‘Christine Green’.

We looked at some of the issues that LAA took action on. Lane didn’t go to Shoreham for any of the protests against live exports from the port, but he was involved in the campaign against Hockley Furs, which went on for three years.

According to a report by ‘Matt Rayner’ [MPS 0246082] its proprietor, Michael Hockley, resigned as a direct result of LAA’s campaign. It characterises the demo held on 16 March (a national day of action against the fur trade) as ‘a series of unrelenting skirmishes’. Lane disagrees with this; he remembers simply protesting outside a string of fur shops.

Towards the end of the day, the activists headed for St John’s Wood, where Michael Hockley lived. The police report provides a sensationalised account of this:

‘the full hatred of the activists towards the man who is seen to personify the evil of the fur trade was expressed through a tirade of angry abuse and noise… with levels of anger fast approaching the hysterical, an all-out assault on Hockley’s home was only prevented by a large police presence’

Lane says this is a ‘gross exaggeration’ of what actually happened. ‘Matt Rayner’ was arrested outside Hockley’s home that day, and seems to have told his SDS managers that LAA activists were ‘amused’ by this. Lane was asked if anyone in LAA would have found such as arrest amusing? He said ‘definitely not’.

How did LAA know where Hockley lived? He remembers ‘Christine Green’ suggesting that they find out by following him home from work one day. The two of them did this in her van, following his taxi, no mean feat in central London.

He remembers being very impressed at the time, although as he says now ‘she was obviously a professional driver’, who’d been trained by the police to tail other vehicles.

‘If it hadn’t been for Christine, we wouldn’t have got that address… that protest at his house would never have happened’

Looking back now, Lane believes that she was actually sympathetic to the anti-fur cause. Like HN11 Mike Chitty ‘Mike Blake’ before her, a while after her deployment ended ‘Green’ resumed contact with people she’d spied on, including a romantic relationship. She is understood to still be partners with one of the activists she’d spied on.

HN1 ‘Matt Rayner’ reported [MPS 0245378] that many of LAA were openly supportive of ALF style direct action and ‘many are personally involved’ (it is unclear how he could possibly have known this).

According to him, LAA was a ‘potent and effective force in the movement’. Lane agrees with this description. He says that the group was ‘very effective’, it was ‘an incredible group’, ‘full of very committed people’, and he believes it was ‘an inspiration for groups around the country’. For once, it appears that a Special Demonstration Squad officer is telling the truth!

The report is, however, not entirely truthful. Lane disagrees with the inclusion of his name on a list of activists said to be ‘involved in disorder and acts of criminality’. He is clear that at this time in his life, he was being very careful not to take part in any criminality as he had no wish to be arrested again. He thinks the SDS sought to justify their infiltration of LAA by making such allegations.

MORE ABOUT HN11 MIKE CHITTY

Lane was asked more about each of the undercovers he encountered, starting with HN11 Mike Chitty. He remembers meeting ‘Mike Blake’ in 1985, when he started a relationship with ‘Lizzie’, a good friend of Robin and ‘Tanya’. As a result, he was welcomed into a very small social group who would hang out at each others’ homes. He says Mike claimed to be a fan of the Welsh rock group Man that Lane had loved in the 1970s.

Spycop HN11 Mike Chitty ‘Mike Blake’

In his statement, Lane refers to another woman as Mike’s ‘victim’. Robin believes that Mike’s first relationship undercover was with her. He didn’t know this woman so well and has no idea when this relationship began or how long it lasted. He says ‘she wasn’t an activist’; ‘she was more like Cats Protection League’. She and ‘Lizzie’ were friends, and he believes that Mike met them both at South East London Animal Movement meetings in Catford.

Mike moved on to ‘Lizzie’ sometime in 1985, and their relationship lasted for several years, until his deployment was coming to an end and he told the people he spied on that he was leaving for America in 1987.

Lane believes that Chitty deliberately targeted ‘Lizzie’ in order to get close to ‘Tanya’ and himself. He had his own place, a ‘bedsit somewhere’, and never lived with her. ‘Lizzie’ shared her flat in Brockley with an ex. Lane remembers being shocked to encounter this man and learn that he was a ‘proper policeman, not an undercover one’.

How did ‘Lizzie’ deal with Mike’s departure? Lane describes her as ‘very resilient’. She was very close to

Mike and upset about the end of the relationship, but seemed to recover. He recalls paying a visit to her house a few years later, with Roz, his new girlfriend. Mike was there, and had obviously come to see ‘Lizzie’.

Lane admits that he was ‘surprised’ and ‘a bit disappointed’ that Mike hadn’t made any effort to meet up with him, and wasn’t ‘particularly friendly’. Roz died in July 1991. ‘Lizzie’ wrote to ‘Mike Blake’ to let him know, including Lane’s address in case he wanted to send condolences. He didn’t.

He has no idea if their sexual relationship was rekindled in 1990. He finds it hard to believe that Mike ever proposed marriage to ‘Lizzie’. She was a close friend of his and never mentioned this. She had already been through one unhappy marriage, and he doesn’t think she would have wanted to marry again.

In April 1994, Lane attended a farewell meal for another activist in Streatham. Reports indicate that two spycops, Andy Coles and Mike Chitty, were present, but Lane does not remember this.

We heard a bit more about a trip to Blackpool Zoo, to protest about the treatment of animals. Around eight people from London travelled up there, at spycop Mike Chitty’s suggestion. As well as him, the group included Lane, ‘Tanya’, ‘Lizzie’, Mike’s ex and a woman called Sue Williams.

They stopped off at a vegan event in the Leeds area then camped in the Yorkshire Dales, again suggested by Chitty, who had brought a tent in his car. He also bought ‘tonnes and tonnes of alcohol’ and they all got very drunk. Lane remembers him and Sue pretending to be sheep:

‘It might sound very silly, but we were young’.

They were three miles from the US military base and listening station at Menwith Hill, and at one point a jeep turned up and the occupants told them to go back to their tent. Mike Chitty said there was sexual activity on that night. But Lane is says that there definitely wasn’t.

OTHER UNDERCOVERS

Lane also knew Belinda Harvey. He didn’t know her so well when she got together with ‘Bob Robinson’, and doesn’t remember the couple living together, but considered her a good friend by the time Bob disappeared from her life in early 1989, after Lane’s release from prison.

Lane has no memory whatsoever of HN87 ‘John Lipscomb’. He does remember visiting the squat in Sudbourne Road, Brixton (and says it had ‘a really nice atmosphere’) but no memory of ‘ELQ’ or ‘John’.

‘ANDY VAN’ (HN2 CREEPY ANDY COLES)

Spycop HN2 Andy Coles ‘Andy Davey’ (2nd from left) on a peace march at RAF Fairford, 1991

In his statement, spycop Andy Coles claimed that near the start of his deployment, he made contact with the Campaign Against Leather and Fur (CALF) to enquire about non-leather work boots. There were only two people involved in CALF; Robin Lane and Roz. It was Roz who imported vegan boots, so she would have dealt with this.

Apart from the van journeys mentioned earlier, Lane didn’t spend much time with ’Andy Van’. He recalls that Andy claimed to like the same kind of music as him, and came round to his flat a few times.

Lane had another girlfriend, a violinist, after Roz. They used to go along to London Vegans events together, and met a French woman there, who was single and looking for love. They set her up to meet ‘Andy Van’ (someone they believed to be perpetually single, and vegan) sometime between 1991 and 1994.

They asked her afterwards how this blind date had gone, and he recalls her feedback:

‘It was OK, it was a bit rough, but she didn’t mind that’

As far as he knows it was a one-night stand and didn’t go any further. Andy never spoke about it.

Lane managed to make contact with this woman recently, after finding out that he had inadvertently introduced her to an undercover police officer. She emailed back, saying she had no recollection whatsoever of that night. She only had one question: was he vegan? Robin doubts it, and reckons he ‘was probably pretending to be’.

We heard more about what ‘Tanya’ thought of ‘Andy Van’. She met him when Robin arranged for him to transport a fridge to her flat. He remembers her saying:

‘I don’t want that man coming around again, he was bit creepy’.

He got the clear impression that she meant creepy in a sexual way:

‘I thought he was bit creepy too, to be honest’.

He says he heard other people say something similar.

Coles claims in his statement that if Lane hadn’t been a target, they might have been friends, but this seems unlikely. Yes, he made use of Andy’s van, but insists they ‘weren’t mates’. He never saw him with a woman, so assumed he was single. He had no knowledge of him his relationship with a vulnerable teenager, ‘Jessica’.

HN1 ‘MATT RAYNER’

Spycop HN1 ‘Matt Rayner’ while undercover, February 1994

In comparison, he thought of HN1 ‘Matt Rayner’ as a good friend, someone he liked. He was into classical music and sometimes came to concerts at the Royal Festival Hall with Lane and the violinist.

Lane recalls a trip to the Ritzy cinema in Brixton together. Like other LAA activists, Rayner went to his parties, such as a birthday party in Holborn.

He remembers ‘Rayner’ as an effective campaigner, who had a van, and laughs as he recalls how he asked him to take over the Northampton van run when ‘Andy Davey’ disappeared off the scene. He was, unsurprisingly, happy to help out.

HN26 ‘CHRISTINE GREEN’

What about ‘Christine’? She was an even closer friend, both of Lane and his now-wife. They socialised together a lot throughout her deployment, which ran from 1994 till 1999. They became friends very quickly, she lived near him and often gave him lifts to meetings. He thought she was a ‘nice genuine person’.

In one report [MPS 0745689] we can see Lane’s signature appears as a witness to hers on a tenancy agreement dated June 1996 for her flat in Central Hill, Upper Norwood. At the time, he thought she asked him to do this because he was a close and reliable friend. He now suspects this was ‘just a very clever and devious way of obtaining my signature’.

She lived alone at this cover address, and Lane used to spend a lot of time there. It was where they collated London Animal Rights News and stuffed envelopes. He didn’t know anyone called Thomas Frampton, or Joe Tex. He says Christine was single, and ‘never in a relationship all the time I knew her’.

He remembers their close friendship coming to an end. One of the group, a woman, had become ‘one of those tree people’, protesting about trees being cut down (possibly in Crystal Palace park, where there was a protest camp at that time). Christine blew out a planned cinema trip with Lane in order to spend time with this woman. His feelings were hurt, and he realised she wasn’t such a good friend after all.

IN RETROSPECT

Lane says that over a decade later, in around 2010, he saw a video of Lambert delivering a lecture and recognised him as ‘Bob Robinson’. He says he wasn’t surprised:

‘there was always something strange about him’

However he was ‘devastated’ when he learnt about the undercovers whom he’d considered good friends, ‘Mike Chitty in particular’. He recalls that he ‘felt so tricked’ by them, he ‘turned into a paranoid person’, suspicious of everyone.

Why was he being spied on when he wasn’t committing any crime? He said earlier that he felt that he was treated as a ‘convenient target’ by the police.

How does he feel now about being reported on by seven different officers, and all this information about him being stored by the police and security services? He still doesn’t understand it. His view now of these spycops operations:

‘I think it’s disgusting. I think it’s an outrage and it’s absolutely appalling’

It was close to 6pm by this point, the end of a very long day of evidence from Robin Lane. He managed to make a joke about billing the spycops for the vegan food they consumed.

The Inquiry’s Chair, Sir John Mitting, thanked him for his ‘good humour’ and noted that he had done a better job of avoiding name-dropping people whose identity is supposed to be private than ‘some former undercover officers’.

Wednesday 13 November 2024

Evidence of Paul Gravett

Click here for video, transcripts and written evidence

Paul Gravett

Gravett was affected by a number of Special Demonstration Squad deployments, including HN10 Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’, HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’, HN2 Andy Coles ‘Andy Davey’, and HN1 ‘Matt Rayner’.

Gravett had previously been scheduled to give evidence about all of them, over one and a half days, however the Inquiry barrister questioning him, David Barr KC, failed to prepare his questions in time. In the event, Gravett was only questioned about Bob Lambert’s operation, and may be called back to give further evidence at a later date.

Gravett has provided a written witness statement to the Inquiry, which was read onto the record but, at time of writing this, has not yet been uploaded to the Inquiry website.

Previous witnesses have been asked to begin with an account of their wider activist lives, but Barr went straight to the point with Gravett, asking when he first met Bob Lambert.

Gravett first encountered Lambert at an Islington Animal Rights jumble sale, although they didn’t speak at that time. Meaningful connection began at a London Greenpeace public meeting about the Animal Liberation Front (ALF) in December 1985.

An intelligence report dated 13 December 1985, written by Lambert himself, documented this first meeting, referring to Gravett as ‘Paul Grottier’ – Gravett testified that this was not an alias, his name had just been misspelt or misheard.

Gravett described how, from the beginning, Lambert made a strong impression. Approximately ten years Gravett’s senior, Lambert was confident and charming. Gravett looked up to him and their friendship developed quickly.

By summer 1986, Lambert was close enough to visit Gravett’s family home, meeting his parents and spending time chatting in Gravett’s room. Lambert hosted parties at his Highgate residence. Gravett recalled he was a drinker who didn’t appear to use other drugs.

Lambert significantly influenced Gravett’s development as an activist and his views on animal rights. Gravett characterized their relationship as having ‘an element of grooming’. While Lambert wasn’t the only influence on his activism, he stood out among others.

‘He brought me along as an activist, increased my confidence a little bit… he stood out [in London Greenpeace] as the person, you know, I think closest to me and willing to help enable me to become a more skilled campaigner’

LONDON GREENPEACE

Barr asked the usual round of questions about the differences between London Greenpeace (LGP) and Greenpeace International (the two were wholly separate), and the links between London Greenpeace and the Animal Liberation Front (ALF).

On the latter point, Gravett’s answers confirmed those of other LGP witnesses:

‘So we are talking about early 1986. The group that I joined then was quite a diverse one in terms of the breadth of its activities, more than most other groups. I would describe it as a green or ecological anarchist group. But broadly, the strands of the group that I felt were most, were most apparent to me in those early days, I would call class struggle and animal rights’.

Lambert was well established within LGP when Gravett got involved. He was a key holder for their office at 5 Caledonian Road, and early on invited Gravett to the office and showed him around. Being a key holder gave him full access to the building, though some individual rooms had separate locks.

The LGP office itself was modest, but it served as a crucial organising hub. Gravett recalled a couple of chairs, a telephone, stationery, lots of leaflets on shelves. LGP had a minutes book for the meetings which might also have been kept there.

On Bob Lambert’s politics, Gravett said:

‘He was first and foremost an animal rights campaigner, but he did certainly have knowledge in other areas. You could talk to him on anarchism. He obviously had a knowledge about that.

‘And he wasn’t, he didn’t just confine himself to animal rights. I remember there were other demonstrations that he went on perhaps, but not very frequently. It was in the main his concern was animal rights campaigning’.

By the autumn of 1986, both men were deeply involved in the anti-McDonald’s campaign. We were shown a photograph of Bob Lambert and Paul Gravett giving out leaflets together outside a branch on ‘World Anti-McDonald’s Day’, 16 October. Gravett was 24 years old at the time.

We were also shown an article written by Gravett in March 1987, which advocated unlawful direct action. Barr asked whether the views expressed in the article were influenced by Bob Lambert or were they views that Gravett held entirely independently of anything Lambert said and did?

‘Well, it’s sometimes very difficult to draw the distinction, because obviously you get influenced by those around you, who you are meeting, who you are seeing a lot of’.

Undercover officers like Bob Lambert were not just conducting surveillance, they were participating, and it is impossible to fully understand the influence they had.

THE ALF SUPPORTERS GROUP AND BROADER CONTEXT

Unlike the other witnesses we have heard from LGP, Gravett was one of the LGP activists in the 1980s who was himself very interested in animal rights, and was involved in the ALF Supporters Group (ALFSG) in 1982 and early 1983.

The cover of an ALF Supporters Group newsletter

Intelligence reports claimed the ALFSG office moved into the London Greenpeace office, but Gravett testifies that this never happened.

Gravett met with imprisoned ALF founder Ronnie Lee about running the ALFSG, receiving clear instructions that no Supporters Group money should be spent on direct action.

The only times he is aware of this rule being broken involved Lambert himself. On one occasion, Lambert pocketed some money from a fundraiser (which had raised £260 for the ALFSG) ‘to buy more glass etching fluid’.

On another, funds from a benefit gig were reportedly used to build incendiary devices. Intelligence reports claimed Gravett was involved in financial management and strategic planning for the ALFSG, but he is clear that his role primarily involved collecting mail.

INTELLIGENCE REPORTS AND DISPUTED CLAIMS

Throughout the period, Lambert filed numerous intelligence reports, many of which Gravett disputes in his testimony. His criticisms of Lambert’s reporting were particularly compelling because Gravett did not shy away from admitting his own political opinions and actions at the time.

Gravett’s first LGP meeting, in December 1985, was addressed by a speaker talking about the ALF. The report of it describes a discussion about animal rights activists needing to move beyond targeting butcher shops and fur shops to focus on major multinational corporations.

While Gravett couldn’t recall the specific conversation, he acknowledged he wouldn’t have opposed such a strategy.

However, the report also refers to another witness (Geoff Sheppard) saying that ‘all vivisectors should be lined up and shot’. Paul Gravett doesn’t remember this comment. He doesn’t recall Geoff Sheppard ever saying that any animal abuser should receive physical violence, and he doubts it was said.

This recorded exchange about shooting vivisectors was also raised on Monday in the questioning of Albert Beale, who was equally sceptical about the language he was reported as having used.

Another intelligence report, dated 15 April 1986, claimed Gravett was involved in criminal damage against animal abusers’ property – which Gravett admitted was true – but also stated he was assisting with the ALF press office in March 1986. Gravett testified he wasn’t involved with the supporters group at that time and wasn’t at the meeting in question.

An intelligence report from 14 April 1987 claims that the ALFSG had moved into the London Greenpeace office, and that that ALF press officer Robin Lane was a regular visitor. Gravett says none of that is true.

A report from 5 May 1987 about a party held at Brunel University, to celebrate an animal rights activist’s release from prison, lists 65 people as being present. Again, Gravett says he wasn’t there despite being on the list.

A significant report dated 16 July 1986 concerned Biorex, a contract testing laboratory in north London that carried out experiments on animals for cosmetics, chemicals and drugs. The report discussed a proposed ‘Biorex Action Group’ supposedly being started by Geoff Sheppard with Gravett and Helen Steel.

Again, Gravett disputed this, noting there was already a long-standing campaign against Biorex (which conducted peaceful demonstrations throughout the period in question). Geoff Sheppard (whose evidence was heard the following day) was also asked to address this proposed Biorex group and likewise said that he did not think it ever existed.

In all, the evidence has exposed extensive inaccuracies of this kind in Lambert’s reporting, and this raises important questions about what Lambert was doing. It seems possible that he invented things to justify his deployment and perhaps even used other people used to cover for his own actions as an agent provocateur.

McLIBEL

Asked about Lambert’s role in producing the factsheet about McDonald’s, Gravett explained that there was a subgroup that worked on the leaflet and reported back to LGP meetings. Lambert was part of the subgroup, Gravett was not.

The Inquiry honed in on this:

‘Q. As someone who was not a member of the subgroup, does it follow you aren’t able to tell us exactly whether or not Lambert wrote anything, and if so what?

A. …he obviously, as a part of the subgroup, did have a substantial input into it, what was in there, yes. I contributed one sentence.

Q. Right.

A. “Revolution begins in your stomach”.

Q. Right. So we can rule that out for Mr Lambert?

A. Yes, he wasn’t guilty of that.’

DIRECT ACTION

There is no doubt that, during the period in question, animal rights activists were involved in direct action, and Gravett did not shy away from that fact.

It is important to recognise that clear lines were drawn around ALF actions, and they unequivocally said that only ‘actions that promote animal liberation and take all reasonable precautions to avoid harm to both human and non-human life’ could be attributed to the ALF.

Barr seemed to struggle with this distinction at times, and Gravett had to point it out:

‘Q. Is it right that at this point in your career as an activist you were carrying out acts of criminal damage against people you considered to be involved in animal abuse?

A. Well not, you say criminal damage against people, that would be violence, wouldn’t it?

Q. Well, the property.

A. The property. I had carried out some acts of criminal damage, I believe, around 1986’.