UCPI – Daily Report: 27 & 28 January 2025 – HN39 Eric Docker

Eric Docker giving evidence at the Undercover Policing Inquiry, 28 January 2025

On 27 and 28 January 2025 the Undercover Policing Inquiry was awash with a great tide of denials, lies and alleged failures of memory from Special Demonstration Squad officer HN39 Eric Docker, a former Detective Chief Inspector who was the unit’s manager from 1986 to 1988.

Docker is the most uncooperative witness at the spycops inquiry so far. He was angry, sneering, and seemed full of hatred for the process.

Given the accountability-avoidance options of appearing either devious or incompetent, he chose the latter, explaining that he didn’t bother managing his officers, scrutinising their work or even reading the intelligence reports that he signed off.

He claims he never asked the officers he managed any questions about what they were up to. He suggested that if they were involved in any misconduct, they wouldn’t tell him; if asked directly, they would lie as they knew the truth would mean the end of their deployment, or even career.

Docker was in Special Branch for many years before joining the SDS. In the early 1980s he spent two years in C squad, which monitors political groups, before moving to uniform. He was on C Squad’s right-wing desk.

He became an SDS manager in 1986, replacing HN22 Mike Barber. He was the unit’s manager when HN10 Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’ was deployed into the Animal Liberation Front and placed a timed incendiary device in the Harrow branch of Debenhams, causing huge fire damage.

He was also the manager of HN95 Stefan Scutt ‘Stefan Wesalowski’ who infiltrated the Socialist Workers Party and, after persistently defying orders, had to be withdrawn from the squad.

Much of Docker’s two days at the Inquiry were taken up with questioning about Lambert, Scutt, and officers deceiving women into relationships.

He was questioned by David Barr KC, Counsel to the Inquiry.

This is a long report, use the links to jump to specific sections:

SDS Structure and Workings

Recruitment, the preference for married men, and identity theft

Targets

Including the Socialist Workers Party, hunt saboteurs, McLibel, and Black justice campaigns

Securing Wrongful Convictions

Perjury and withholding evidence from courts

Bob Lambert in the Animal Liberation Front

His catalogue of criminal activity, mainly focused on the incendiary devices in Debenhams

SDS Culture, Methods & Activity

Paranoia, persecution and bigotry

Relationships

Mike Chitty and ‘Lizzie’; Bob Lambert and ‘Jacqui’, ‘RLC’, and Belinda Harvey

Stefan Scutt

The secretive officer who went off the rails

Making Changes

Report and legacy: reviewing what went wrong and making recommendations, yet still defending everything that was done

SDS Structure and Workings

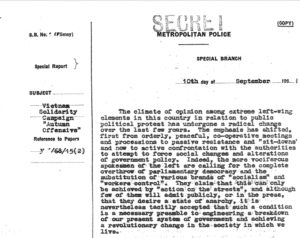

SERVING THE SECURITY SERVICE

At the beginning of Docker’s deployment in 1986, a Security Service (MI5) document [UCPI0000029267] described him as:

‘well-disposed towards us but deeper and more devious than his predecessor.’

Asked why the Security Service might have used the word ‘devious’ to describe him, Docker says he would have been very quiet in that introductory meeting with them. He is clearly irked by the assessment.

He had worked with the Security Service before, and says there were no issues then. He went on to say that his predecessor Mike Barber was ‘not devious at all’.

Docker says he wasn’t privy to all of the meetings between Special Branch’s senior officers and the Security Service but they generally worked well together, although he admits that there may have been some ‘mistrust’:

‘We never got any idea what they were doing with our product. We never got very much feedback from them. It didn’t seem to us as if we were on an even playing field a lot of the time.’

Docker says that debriefs of spycops by the Security Service were voluntary for the SDS officers themselves. If they didn’t want one, that was the end of it.

Asked if the close relationship with the Security Service made the SDS feel like an elite unit, Docker emphatically rejects the suggestion, saying it was just another unit in Special Branch. However, he agreed it was exceptional in terms of the work it was doing and was not bound by the ordinary rules:

‘the very nature of the job they were doing could not be done by a police officer observing every single rule and regulation that he or she may have to abide by.’

Docker admits that he never saw any ‘specific authority’ from the Home Office for the spycops undercover operations. He says he was instructed by Special Branch, and knew that an SDS Annual Report was sent to the Home Office in order to be granted permission to continue, so he assumed that what they were doing was allowed.

‘When I went to SDS I had no knowledge of it, I had no understanding of how it worked, and I had to learn on the job.’

However, he is adamant that ‘we did not make it up as we went along’ and says he had a Detective Chief Inspector and Chief Superintendent he could consult.

RECRUITING MARRIED MEN

Docker was responsible for the recruitment of HN87 ‘John Lipscomb’, HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’, and HN25 ‘Kevin Douglas’. He’s described the process as being done ‘on a wing and a prayer’.

Later on, Docker supposedly made improvements to the spycops recruitment process, but these three were all recruited before that.

He met these officers’ wives before a final decision was made to recruit them. He says this was to:

‘make sure that they were fully supportive of what their partner was proposing to do. And to explain to them how it may affect their whole lifestyle.’

Docker says that being married would help ensure spycops went back home to their families. He says he never talked with his bosses about whether or not it would deter them from having sexual relationships while undercover.

Docker asserts that he didn’t wholly agree with the principle and – against his Commander’s advice – he recruited single men, who he says proved to be good officers.

Given his claim that he had no idea about any of his officers deceiving women into relationships, and presumed they’d hide any involvement in criminal activity from him, it’s hard to see how he feels able to appraise their calibre.

Perhaps he didn’t think abusing women, committing crimes, or being an agent provocateur mattered, so those things had no bearing on his judgement about whether the officer was good.

Docker claims that the topic of sexual relationships whilst undercover never came up when he was with the spycops either. He can’t recall any conversations in the SDS office about this risk, the temptation, or the restraint required:

‘if I had asked any officer to their face, whether they were having any sort of sexual liaison, I would’ve been blanked straight away or there would’ve been a total denial… that sort of information, they would’ve kept to themselves.’

Essentially, he’s asking us (and the Inquiry) to believe that by coincidence half the officers independently did this, while deployed and overseen by managers who’d done the same when they were undercover, without anyone ever mentioning sexual relationships at all.

He says he told recruits that the job involved much more observation than anything else, telling them that they have two eyes, two ears, and one mouth, and these should be used proportionally.

LEGEND BUILDING & IDENTITY THEFT

We move on to hear about ‘legend-building’, the spycops’ development of their undercover persona, something Docker has covered in his witness statement [MPS-0749045].

For the Inquiry, David Barr KC highlighted the fact that some officers – e.g. HN10 Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’ – chose to use identities which would make them appear years younger than their real ages. Docker says he didn’t know about this.

Docker says decisions on how to select a dead child’s identity to steal were left to the individual spycop. He claims not to know any details about how spycops built their legends on dead children’s identities. He is very, very defensive.

He is also contradicting the findings of Operation Herne (a police investigation into spycops). Its first report, published in July 2013, was stark and unequivocal on this point:

‘It is absolutely clear that the use of identities of deceased children was an established practice that new officers were ‘taught’. It was what was expected of them, and was the means by which they could establish a cover identity before they were deployed.

‘Whatever their views are now about this practice, this was not done by the officers in any underhand or salacious manner – it was what they were told to do.’

Docker responds to all questions on the theft of dead children’s identities with non-committal answers like ‘it could be’ and ‘it’s possible’, even when asked if senior officers knew. In fact, as he says, the practice was long-established and a number of the SDS officers who had used it had since been significantly promoted. We can be sure it was known about in the higher echelons of the Met.

Docker’s only definite answers on this topic were that HN5 John Dines’s use of a second fake identity wouldn’t be approved, and nobody mentioned picking an age younger than the real one in order to be more attractive to women (because his story is that nobody mentioned that in any way ever).

Barr asked Docker if he ever thought about whether this identity theft was legal.

‘Sadly I did not.’

He says that he had no reason to question such an established practice, and denies being aware of HN297 Rick Clark ‘Rick Gibson’ being presented with the death certificate of Richard Gibson in the 1970s.

This is another peculiar denial. In 1993, a few years after Docker’s time, an SDS Tradecraft Manual was compiled containing very detailed instructions on committing this kind of identity theft. It included the following warning:

‘we are all familiar with the story of an SDS officer being confronted with his ‘own’ death certificate’

That incident happened in 1976, and was universal knowledge in the unit in 1993, but supposedly it was unknown to its boss Docker in the late 1980s.

Barr reads from the ‘unreserved’ apology made by the Met to the families whose deceased relatives’ names had been stolen by spycops, Docker says that he now does not condone this ghoulish practice but it was a long time ago. He points out he was only there for two and half years and at the end had made some recommendations for changes.

Targets

WHO TO SPY ON?

Docker says that Special Branch squad chiefs (Chief Superintendents) suggested targets, and sometimes the spycops made their own suggestions which these squad chiefs would be asked for agreement on. He says he was just the man in the middle, with very little influence.

He says that in his opinion both the Socialist Workers Party and the Hunt Saboteurs Association deserved to be targeted by spycops – and refers to the hunt sabs as if they were bombers:

‘animal rights activists were very active in hunt saboteuring, in placing devices, et cetera, and they needed to be targeted.’

Barr asks if he made any distinction between one kind of animal rights and another – between those who leafleted about veganism and those who planted devices?

He said both were important to spy on, even those that just leafleted:

‘they had a propensity to cause minor public disorder… Most of the time it would not really have bothered us, but it’s, as I said, a way in for an SDS officer and therefore it’s important.’

We’re shown a spycops report of 8 December 1987 [UCPI0000023760] about the Brent Campaign against the Prevention of Terrorism Act meeting. Speakers included Labour MPs Ken Livingstone and Clare Short. There are lots of details of Livingstone’s speech (he was a long-term target of Special Branch and is a core participant at the Undercover Policing Inquiry).

Docker admits it’s not public order or subversion, and it is legitimate speech.

He adds that just because someone is a democratically elected Member of Parliament, this doesn’t stop their speech being reported by spycops, and confirms that there was no criticism of that from his senior officers.

McLIBEL

There’s a spycops report from 10 October 1986 [MPS-0742720] about the printing of London Greenpeace’s fact-sheets about McDonald’s which are described as ‘clearly libellous’.

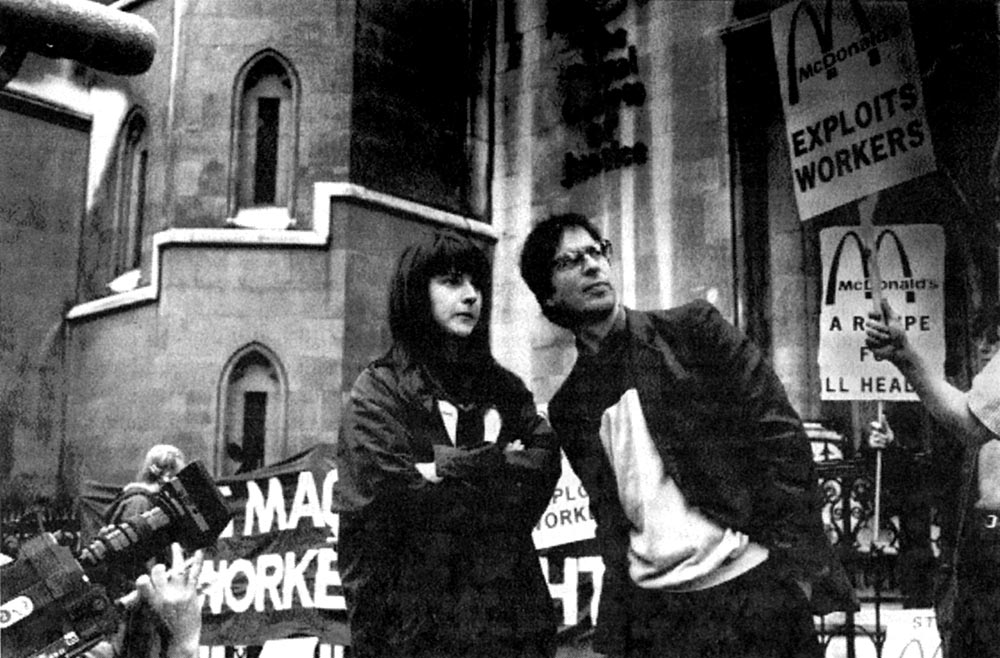

The McLibel 2, Helen Steel and Dave Morris, at the Royal Courts of Justice (Pic: Nick Cobbing)

Docker says this was fairly early in his time in the SDS, and that he knows nothing about any direct contact between Special Branch and the corporation.

He doesn’t recall paying much attention to the phrase ‘clearly libellous’, or doing anything about this at the time.

He also denies knowledge of spycop Bob Lambert’s role in the production of the fact-sheet that led to the McLibel case, the longest trial in English history. Docker says that this isn’t something he would have known about, six months into his role, as it would have been the responsibility of his DCI, HN115 Tony Wait.

Barr points out that Docker saw, and checked in with, Lambert twice a week. Docker says that he attended many such meetings over his two and a half years, and he can’t remember all the details now.

He says as far as he knows there was no communication between the SDS and McDonald’s. He denies knowing Sid Nicholson or Terry Carroll, former police officers who went on to work for McDonald’s security. Nicholson testified that the entire McDonald’s security department was ex-police, and they would often exchange information with the police.

Docker said he was unaware of the private infiltrators from McDonald’s who were in London Greenpeace, even though HN5 John Dines reported about them. The most he’ll confirm is that, when asked about whether there was even a campaign against McDonald’s at the time:

‘I believe so.’

David Barr KC asks Eric Docker if his memory is going to be this vague the whole time. He answers to say basically yes.

TREVOR MONERVILLE CAMPAIGN

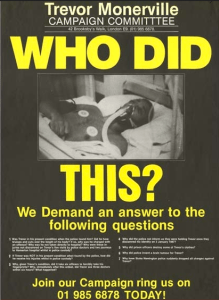

Trevor Monerville campaign poster

We see a report [MPS-0740393] with a title saying it’s about the Socialist Workers Party, but with a lot of content about the Trevor Monerville campaign, one of a number of Black justice campaigns that were spied on by the SDS.

In January 1987, 19-year-old Trevor had been held incommunicado at Stoke Newington police station before being rushed to hospital with a head injury. He was left with permanent brain damage. The only reasonable explanation is that the police gave him a very severe beating.

Police refused to even admit they’d had contact with him for some time after. His family campaigned to get the truth about who had caused such horrendous injuries.

Trevor’s father John’s witness statement to the Inquiry refers to the campaign being listed in the 1987 SDS Annual Report [MPS-0728976] as one of those ‘directly penetrated or closely monitored’ (the name isn’t visible in the report online, presumably it’s one of those redacted for public viewing). Reporting on the Justice for Trevor campaign continued for many years afterwards.

Why would the SDS spy on a lawful campaign? Docker says it was because of the Socialist Workers Party’s support of the campaign:

‘which would of course be of interest.’

Barr points out that the report itself explains that one SWP activist has joined the campaign but has little influence and is rather isolated. It’s clear from the report that the SWP hadn’t got anywhere. It’s surely legitimate for the public to campaign about an issue like this.

Q: There’s nothing to suggest that the Socialist Workers Party is doing anything here that is going to interfere with public order or be unlawful, is there?

Docker: Not at that point.

Docker keeps saying that this report was about the SWP, but is forced to admit that spying on groups fighting for racial justice is and was ‘sensitive’.

Barr goes on to say that if anyone had discovered that spycops were reporting on a Black justice campaign it could have damaged community relations and caused public order trouble. Was any thought given to this?

‘my honest answer is no’

Docker admits that the SDS gave no consideration to the Monerville family either. He insists that the SWP had a habit of hijacking campaigns. But even if the SWP did try to hijack the Monerville campaign, couldn’t the family have dealt with it themselves? Was any thought given to them at all?

‘I am sad to say the answer was no’

Securing Wrongful Convictions

Barr next asks about the arrest of Steve Curtis in 1986 at a demo outside the US Embassy in London, at the time of the US bombing of Libya. HN10 Bob Lambert was asked to give evidence in court for Curtis’ defence.

Commander Phelan, one of the senior officers, felt that Lambert should not give evidence in this case. If he did so using a false identity and not telling the whole truth, he would be perjuring himself.

Docker recalls that his immediate boss, HN115 Tony Wait, agreed with Phelan, but says he doesn’t remember what he thought himself at the time. Docker says he remembers Lambert being told not to appear, but has no idea if he did or not. Curtis was convicted.

Docker says that spycops were allowed to commit ‘minor offences’. Asked what severity of offence would be left to run its course through the courts – with spycops appearing in their cover names – he mentions ‘obstructing the footway’ and claims anything beyond that level wouldn’t be allowed.

The Home Office had issued clear and unequivocal guidance as early as 1969 that if the use of any kind of informant might lead to a court being misled, that person should be withdrawn or outed. The SDS and, it seems, the wider Met just ignored this.

This led to an uncharacteristically frank, direct and honest exchange between Docker and David Barr KC:

Docker: He’s been arrested, right, fine, okay. Nothing serious. Let it carry on.

Q: That is a decision, isn’t it, that requires the officer to appear before a court in a false identity?

Docker: Correct.

Q: The court is misled?

Docker: Correct.

Q: That’s wrong, isn’t it?

Docker: Yes.

Q: Did you address your mind to it at the time?

Docker: No.

Q: Should you have done?

Docker: Maybe.

Q: You should’ve done, shouldn’t you?

Docker: Maybe I should’ve done, but we’re talking a long time ago and that was the established practice then.

SPYCOP BOB LAMBERT ARRESTED

A report of 3 March 1987 [MPS-0526789] shows Bob Lambert was arrested hunt sabbing in Horsham during his spycops deployment.

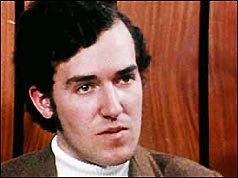

Spycop HN10 Bob Lambert while undercover in the 1980s

Docker says it was normal to send someone from the SDS office if an undercover officer was going outside the Met Police area.

He was in the police station when Bob Lambert was brought in from being arrested. He says he probably spoke to Sussex Special Branch and told them that he was covering an informant, rather than a spycops officer. When no charges were brought, he says he didn’t tell them any more.

The report says that Lambert’s cover was not compromised by this arrest, and that during his time being held in the cell with other arrested activists, Lambert was able to gain useful intelligence.

Docker insists that this is true, although there is no record of this intelligence and he can’t remember what it was. He rejects the suggestion that he was trying to put a positive spin on a bad situation.

The report was accompanied by a note from Special Branch marked ‘DAC [Deputy Assistant Commissioner] to see, please’. It’s marked with a file number, 588/UNREG/694E.

Docker describes it a ‘policy file’, but then pretty much agrees it was for keeping records of SDS officers’ involvement in adverse events such as arrests and traffic collisions.

He said he never looked at the contents, and they were kept over at Scotland Yard, as if that made them hard to get to. Which is odd, given that he later said that he was in contact with his Chief Superintendent at Scotland Yard ‘almost every day’, and emphasised how close it was:

‘Ten minute walk, maximum.’

He says ‘I wouldn’t have had access’ to the file but admits that he could easily have got access if he had asked. He doesn’t agree with Barr’s suggestion that it would have been good to look at the file when he joined the spycops unit.

Bob Lambert in the Animal Liberation Front

ANIMAL RIGHTS

Lambert formed an Animal Liberation Front (ALF) cell which, amongst other forms of property damage, placed timed incendiary devices in shops that sell fur. The devices were set to go off in the dead of night, producing just enough smoke to set off the sprinkler system which would then douse the stock, making the furs (and other items) worthless.

Barr suggests that during Docker’s time running the SDS, animal rights was top of the agenda.

Docker quickly tells him:

‘I didn’t have the agenda. The agenda was held by the squad chief where animal rights were dealt with, which I suspect was C Squad at the time.’

He then immediately admits that animal rights activists’ activity was indeed ‘top of the list’ for him.

Animal Liberation Front (ALF) actions were carried out by individuals and small groups. Docker agrees that they had a ‘cell structure’, and that anyone wanting to infiltrate these groups had to show they were ‘up for it’ and capable of keeping their mouths shut.

Did he ever discuss how his officer Bob Lambert would inveigle himself into the animal rights movement?

‘He was a very shrewd man and I would not have discussed something like that with him because he would’ve had his own ideas.’

So, Docker left him to get on with things using his own initiative and methods? Docker claims Lambert would definitely have been reminded not to commit crimes. And they would have had one-to-one meetings with him.

PERMISSION FOR CRIME

The next document we see [MPS-0730597] is from January 1993, after Docker’s time. It talks about spycops infiltrating animal rights groups:

‘in order to gain full acceptance and trust, participation in ‘illegal’ activities is essential. This level is progressive from inspections of premises, where no criminal offences are actually committed, through the housing of liberated animals, daubing and other minor damage to premises, through to product contamination, arson and the use of improvised explosive devices.’

This would appear to sanction officers planting incendiary devices as Lambert did (though he and Docker are at pains to deny it).

Docker says ‘you would have to draw the line somewhere’, but it’s hard to see from this document where that line would be. Barr points out that there don’t seem to have been many lines for the spycops.

Barr affirms that spycops’ intelligence could not be used for criminal prosecutions without risking the officer’s cover, and so was not being gathered for evidential purposes:

‘That would not have been their role’

Docker says he didn’t see a problem with this, as the spycops were told not to get ‘heavily involved in criminality’. He goes on to claim that if they did, their posting would be over.

He doesn’t understand the point Barr is making: to have a long-term infiltrator who stays in post after a major criminal act, they would have to be involved in that criminal act in some way.

Docker is asked if he remembers the campaign against the Biorex vivisection laboratory, and he says he doesn’t. Did he know about Lambert’s involvement in an arson attack at a house that belonged to one of this company’s directors? No.

Docker goes on to say that if he had known, Lambert’s deployment would have been ended. He should have come to the spycops managers first to discuss it.

Spycop HN10 Bob Lambert (right) at protest against dairy firm Unigate, 1980s.

Docker insists that Lambert was intelligent and would never have risked his spycops career by taking this kind of action. He doesn’t say how it was a risk when, according to his description, spycops worked unsupervised and their managers only knew what they were told.

The managers didn’t – indeed, usually couldn’t – check the veracity of what was reported. They wanted reports full of juicy details. The spycops were only judged on whether they supplied them, not on how they got them, nor on how true they were.

The managers, in turn, could not have their reports fact-checked by more senior officers, so they were in a position to know their spycops were committing crimes and safely keep that knowledge to themselves.

Asked about paint stripper being poured on a Biorex director’s car, allegedly by Lambert, Docker repeats that he’s sure Lambert would never have done such criminal acts.

He also denies knowing about Lambert’s use of etching fluid to damage plate glass windows, or his asking activists to buy it for him.

As for whether this kind of action would be acceptable, Docker says the decision would have been up to far more senior officers than him.

INCENDIARY CAMPAIGN

We were shown a report dated 9 June 1987 [MPS-0740088] about a forthcoming Animal Liberation Front (ALF) campaign which might be using incendiary devices. It mentions secret meetings between ALF activists from around the country. Docker says the mention of targets in London was of great interest.

Did Lambert attend any of the ‘secret meetings’ mentioned in this?

‘I don’t know.’

Lambert has said he was at a meeting in Manchester. Any travel outside of London by spycops would surely have been approved by Docker as the unit’s manager.

Docker considered Lambert to occupy a position of trust within the animal rights movement, due to the quality of the intelligence he was delivering. He admits that there was no actual scrutiny of this intelligence, or its accuracy. They just took Lambert’s word for it.

Docker rejects the idea that there was a complete lack of scrutiny of what Bob Lambert was up to in summer 1987. Asked what scrutiny there was, he can’t describe or specify any.

Asked what advice or instructions he gave Lambert, he retorts that ‘he didn’t need me to tell him how to proceed’. It is very clear that Lambert was not being closely supervised by anyone.

Animal rights activist Paul Gravett said in his witness statement that he put on a benefit gig in Slough, and the funds raised were used for ALF actions. Docker says Lambert never told him that he’d been involved in fundraising for ALF actions.

DEBENHAMS: PREPARATION

The cell decided to target Debenhams shops that sold fur. Andrew Clarke and Geoff Sheppard would eventually be convicted for this. However, three shops were targeted simultaneously. Clarke, Sheppard, and numerous other people who knew Lambert at the time say Lambert planted the third incendiary device, in the Harrow shop.

Asked if he knew that Lambert had taken part in the reconnaissance of Debenhams stores which were then targeted in the incendiary device campaign, Docker replied:

‘I really can’t remember.’

It’s very noticeable that the last report filed by Lambert before the Debenhams action on 12 July 1987 was dated 9 June. Why are there no reports from him at all from the month immediately before the incendiary devices were planted? Lambert would normally have been submitting two or three reports a week.

Docker claims he didn’t notice this lack at the time and that he must have assumed that Lambert was consistently busy doing other things and just didn’t have time to write any reports.

However, at the end of his second day of questioning, Docker completely contradicted this and said that it would be extremely odd to go a month without a report and he’d demand an explanation:

‘Unless they were away for some reason for a month, which was very, very unlikely, I would expect to see something from them. Otherwise, I’d be asking them why.’

He insists that he doesn’t believe Lambert was involved in the Debenhams campaign or responsible for planting an incendiary device. He strongly denies that managers would have allowed him to take part in such a serious criminal action.

Docker says he can’t remember anything that Bob Lambert said or did after the Debenhams attacks. He can’t even remember what he thought himself, nor what he asked Lambert.

DEBENHAMS: REACTION

This action was a very big deal, and squarely in the area that Lambert was working in. Whatever his involvement he would surely have phoned in to the SDS office.

‘I can’t remember now.’

Docker says the managers ‘probably would have seen him on the Monday’ at the safe-house meeting (this would have been 13 July 1987) and suggests Lambert would have delivered an oral report to the other spycops. But he says he’s just guessing this as, once again, he doesn’t remember.

Docker says he didn’t task Lambert to find out who’d done it, he wouldn’t have needed to because Lambert would already be on the case and would volunteer the information if and when he had it.

Firefighter in the wreckage of Debenhams Luton store after 1987 incendiary device placed by Bob Lambert’s Animal Liberation Front cell

We now know that Geoff Sheppard was involved in planting one of those devices. However, his name is not in the report that Lambert submitted.

In his evidence to the Inquiry, Lambert said that he suspected Sheppard was involved. Docker claims he can’t remember whether Lambert shared that suspicion with him.

Docker insists that immediately after the attacks, they just told Lambert to remain in post, and not do anything in particular. Docker says Lambert ‘would not have divulged his sources’ to the SDS managers. This is an incredible claim, given that it was basically a spycop’s job to do precisely that – get information from activists and tell their managers who was doing what.

Docker says Lambert didn’t need to tell them as he could put it in a report. But, Barr points out, he didn’t put it in a report. Or if he did, that report has gone missing.

There are audio recordings of someone claiming responsibility for the Debenhams attacks. Did Docker ever hear these? Were they played to Lambert, to see if he could help to identify those involved?

Docker says he wasn’t even aware of these recordings:

‘It’s the first I’ve ever heard of it’.

It was usual for the ALF to phone the police and claim responsibility for an action. A recording should have been anticipated, but Docker appears to be saying it didn’t occur them to find it.

Barr asks outright:

‘Is the reality that you didn’t need Lambert to listen to a recording because he was in the cell and had participated in the attacks?’

Docker, of course, says no.

SUGGESTING CULPRITS

Immediately after the Debenhams incident, the Security Service asked spycops who the culprits might be. A Security Service report listed the names of people suspected [UCPI0000031267]. Docker suggests these could have come from Lambert. So why are Paul Gravett and Geoff Sheppard not on the list, given that Lambert knew they were responsible? Docker says he doesn’t know.

Barr asks if there was a decision for Lambert to only report selectively at this time? Docker says he would ‘never use the word selective’ and insists that he wouldn’t have known that Lambert was doing this.

‘If he misled me I wouldn’t have known about it in the first place.’

He turns and nods to the police lawyer as he says this.

We also see a report which says that the incendiary devices were manufactured by Andrew Clarke at his home address, and that only a very small number of people know this. Why is the source of this info not recorded?

According to the notes of a meeting of very senior officers held on 14 July 1987 [MPS-0735357], it was agreed that Docker be tasked with providing information about which room Clarke occupied in his house. He says he would have spoken with Lambert after this meeting.

Docker says ‘the source is never recorded’ in spycops reports. This seems to be a reference to the fact that the name of the undercover officer is not usually included. Barr points out that he is actually referring to the activist ‘source’ of this intelligence, which would normally be identified (as Lambert claimed in his evidence that this was second-hand information that he’d gained via an activist source, rather than something he had direct knowledge of).

A further report [MPS-0735387] features a list of other suspects whose addresses should also be searched. It includes Lambert’s cover name ‘Bob Robinson’, but still no mention of Geoff Sheppard, the person Lambert said he got the details from.

Docker can’t explain this. He says he doesn’t remember Lambert telling him. However, not only did Lambert tell the Inquiry that he did indeed name Sheppard to Docker, but Docker also admits that he knew Sheppard was someone with a history of this kind of action.

Q: He’s an obvious suspect, isn’t he?

Docker: Yes.

Q: Are you sure you can’t help us as to why he’s not on the document?

Docker: I don’t know. I simply can’t answer your question.

Q: Did you spot the omission at the time?

Docker: Maybe I didn’t.

Asked why this list of suspects is far longer than the one given to the Security Service, Docker says it wasn’t up to him to ensure intelligence was shared with them. He adds with a smirk:

‘That was NOT my responsibility’

NEXT INCENDIARY CAMPAIGN

Another report, from 24 July 1987 [MPS-0735386], suggests a further incendiary campaign was being planned for the autumn. This one would target other retailers including Harrods and C&A. Docker says this issue was something the SDS wanted to keep a ‘firm’ grip on. He says he didn’t ask Lambert how he got the information or where it came from.

A spycops report from 11 August 1987 [MPS-0735383] says Andrew Clarke manufactured the incendiary the devices and planted two in Luton, and:

‘Two close and trusted comrades were responsible for planting devices at the Harrow and Romford branches, their identity is not known at present’

Though unnamed in the report, these two were, of course, Lambert and Sheppard.

It also says that Clarke plans to move the manufacture of devices to a different address.

Docker says he can’t remember talking to Lambert about it. But he agrees it proves:

‘Bob was at the top echelon of the Animal Liberation Front and had access to very, very detailed intelligence of their intentions’

Yet he still refuses to admit that this report shows that Lambert was in the ALF cell.

Docker claims he would have been speaking to Bob Lambert twice a week at the safehouse meetings, and also outside of that. He can’t recall anything about what was said, but is sure he didn’t ask him how he was getting intelligence.

He claims not to remember feeling any inquisitiveness about the precise nature of Lambert’s role at this time. Even though, he admits, he played a part in relaying Lambert’s intelligence back to senior officers during the summer of 1987, so it seems they must not have questioned how they were getting it either.

We see a spycops report [MPS-0735382] about the meetings of an active ALF cell, with just four people present: two are Clarke and Sheppard, one is ‘presumably’ Lambert who was writing the report. Who is the fourth? The exchange was one we heard a lot:

Docker: I don’t know – you’d have to ask Bob.

Q: Did you ask Bob?

Docker: No.

NAMING SHEPPARD, WATCHING CLARKE

According to this report, dated 18 August 1987, Sheppard planted one of the devices. This is the first time Lambert has reported his name – over a month after the action. Docker denies remembering what he said about this at the time.

The report mentions Debenhams being given a ‘deadline’ by which to stop fur sales. Docker says that he doesn’t know of any communication between Debenhams and Special Branch, indignantly saying this wasn’t his ‘remit’.

Geoff Sheppard (left) and Paul Gravett in the 1980s

We hear that the police are keen to start ‘evidential surveillance’ of Andrew Clarke in August 1987 with a view to catching him making devices and securing a conviction. The ‘operational security concerns’ associated with this are going to be discussed with the SDS, in the shape of Docker.

What were these concerns? Rather than answering Barr’s question, Docker first makes the bizarre claim that ‘in my experience, all surveillance is evidential’.

This completely contradicts the general method and purpose of the SDS, and of Special Branch as a whole. They were specifically tasked to gather intelligence rather than evidence. Their material was taken on trust and not for use in court cases.

Barr asks if the ‘operational security concern’ was that he wanted to ensure that Lambert didn’t appear in any surveillance photos, as this might have raised questions about him at any trial.

Docker agrees that they would indeed have preferred to avoid this. He says that he would have told Lambert about the surveillance. He would have wanted to advise Lambert to distance himself from Sheppard. He adds that members of the surveillance team would probably have recognised Lambert.

The next ‘briefing note’ dated 24 August 1987 [MPS-0735381] seems to combine intelligence from Lambert with information gathered through surveillance. Docker says he doesn’t remember this. It recommends that Helen Steel’s address not be searched, ‘for source protection’ reasons.

Docker is asked what this means. He claims not to know what this referred to and says he can’t remember if he discussed this with Lambert at the time or not.

Before the spycops inquiry stops for lunch, Mitting intervenes. He asks Docker to ‘reflect’ on the August meetings of the ALF cell, and exactly what he said to Lambert about his participation in that four-person group. This appears to be Mitting telling Docker ‘you obviously know, so fess up or we’ll assume you’re lying’.

We return from the lunch break to hear Barr ask Docker again what he said to Bob Lambert about his participation in an ALF cell. Docker continues to claim he never spoke to Lambert about this. When asked why not, he says it simply ‘didn’t occur’ to him.

SEARCHING LAMBERT’S FLAT

It’s said that HN51 Martin Gray had been informed about the identity of Lambert as the source, and a plan was hatched for ‘a specifically selected SO13 team’ to conduct a search of his address (SO13 is the Met’s Anti-Terrorist Branch who were investigating the Debenhams incident).

Asked if he’d introduced Gray to Lambert, Docker says Gray ‘would have known him anyway’.

As for the ‘specifically selected’ team, Docker is adamant that the search team would not have been informed that this was an undercover officer whose address they were searching. The search eventually took place in September, accompanied by HN32 Michael Couch, who has told the inquiry that everyone on it knew Lambert’s true identity.

He agrees that if Lambert had been arrested at this time, as a suspect in a terrorist offence, he probably would have been interviewed under caution.

We see a report from the end of August [MPS-0735376] saying that the attack planned on Harrods has been postponed. This was because of a large number of liberated laboratory rats that needed to be moved. Asked if Lambert took part in the reconnaissance of Harrods, Docker says he doesn’t know, and that he never asked Lambert how he’d gained this intelligence.

He says he only vaguely recalls the incident involving the ‘200’ liberated rats. David Barr remarks to Docker that it was surely a memorable thing, and Docker agrees, but then says he only recalls it ‘very, very vaguely’.

Docker obviously remembers a great deal more than he is letting on. He is desperately trying to pretend that he can’t recall events whilst every aspect of his body language shows he knows exactly what happened.

The report explains that the 200 lab rats needed to be moved on from the location where the devices were being made before the assembly could take place. Barr asks Docker if Lambert was directed to move the rats so that Clarke and Sheppard could be arrested. Docker can’t recall.

He says he doesn’t know how this related to the incendiary attacks being postponed. He doesn’t remember what part Lambert had in transporting the rats, or anything about authorising or prohibiting this involvement.

Barr points out that the longer any delays lasted, the longer any surveillance operation would need to continue, and surveillance isn’t cheap.

‘IN ALL PROBABILITY’

In a bit of a breakthrough, Docker finally admits that Lambert may well have been a member of the ALF cell:

‘In all probability he might well have been. But he never admitted that to me and I’m not sure that I ever asked him about it anyway.’

Barr suggests that this is because if Lambert had admitted that he was in the cell, it would have created a ‘dilemma’ for Docker. He would have had to investigate further and prohibit Lambert from the criminal activity that was producing such high-quality reports.

Docker rejects that this was in any way linked to his obvious reluctance to pull Lambert out of his deployment. He still doesn’t want to blame Lambert for anything, saying that he should perhaps have looked into Lambert’s involvement more at the time:

‘Perhaps that’s my failing, not his.’

He adds that he doesn’t believe that Lambert would do anything that would make him liable to prosecution. Neither Barr nor Docker raise the fact that the culture of exceptionalism in the SDS means Lambert may well have believed himself to be immune.

INCENDIARIES POSTPONED

A Special Branch briefing note of 28 August 1987 [MPS-0735377] says the next incendiary action is said to have been postponed, till 11 September. Again, Lambert is clearly reporting from inside the ALF cell.

Docker says ‘Clarke and Sheppard were always put forward as the main protagonists’, and that he never asked who else would be involved in planting these incendiary devices.

Was there a plan to not arrest certain people? If Lambert was the only one not arrested it would have drawn suspicion upon him. Were others involved in the cell to be omitted from the arrests too? Docker says, again, that it wasn’t his problem to ponder. He says the decision about who to arrest would have been taken by a Chief Superintendent or Commander.

This contradicts other evidence we have seen of the SDS frequently intervening in policing operations and court processes where their number one priority is always protecting the existence of the unit and the secrecy of their ‘source’.

A spycops report of 4 September 1987 [MPS-0735374] claims there will be further intelligence to come over the weekend about the plans of Andrew Clarke and Geoff Sheppard in building more incendiary devices. Docker can’t remember anything about it.

We were then shown a briefing note by Docker’s boss, TN0042, dated Sunday 6 September 1987 [MPS-0735375]. Docker had rung TN0042 on a Sunday morning to tell him about a change of plan for the making and placing of the next set of incendiary devices. Clarke and Sheppard were reported as experimenting with a new design, and there was a date set for placing them.

This was important information – important enough to bother your boss with on a Sunday morning – and yet Docker didn’t seem to have asked who’d joined the conspiracy.

He agreed that the police would want to arrest whoever was involved, but he didn’t ask Lambert who it might be beyond Clarke and Sheppard. He can’t explain why.

‘I don’t recall being inquisitive, no.’

He says he was confident that the ‘two protagonists’ would be arrested and so the action wouldn’t take place, and that was enough.

MAKING ARRESTS

The report mentions Andrew Clarke’s connection to activists in Manchester. Docker can’t remember anything about it. Asked about spare incendiary devices, Docker can’t remember that either.

Docker can magically now remember something, though: there was a plan that Lambert would ring the SDS office after Sheppard and Clarke had been in the flat for two hours, so that it could be raided and they would be caught red-handed.

Operation Herne (a police self-investigation into spycops, 2011-2016) spoke to Docker. Their evidence is proving very useful at the Inquiry as the spycops tended to be a lot more candid when speaking to fellow officers in circumstances that were less open to public view.

According to Herne [MPS-0738106]:

‘N39 [Docker] did recall that on the day of the arrests of Clarke and Sheppard he had a difference of opinion with Dave Short, (C Squad Chief Superintendent) and Short said something like ‘the man’s out of control, you’ve lost him’.

Docker says he is unsure what Short meant and can’t recall anything else. He was confident that Lambert would act as arranged, calling when Clarke and Sheppard had been alone for two hours, then the raid would take place.

‘He didn’t let me down. And the arrests were made.’

He remembers disagreeing with Short’s assessment at the time, and says it’s a shame that Short is now dead so can’t tell the Inquiry what he thought.

Barr asks if he’s sure that Short saying ‘the man’s out of control’ was referring just to the arrangement of that weekend? Was he maybe referring to the situation with the rats? Or Lambert’s conduct more widely? Docker insists that Short was referring only to the events of that weekend.

RAIDING LAMBERT

There is evidence that search warrants were applied for in relation to other addresses, including Lambert’s cover flat. Docker thinks that Lambert was aware that his flat would be searched, but doesn’t know if he knew it would only be ‘cursory’.

He thinks Lambert would have been aware that there was a possibility that he might be arrested. Docker says Michael Couch, a former member of SDS staff, was present during this search, not for Lambert’s welfare but to ‘make sure everything was done properly’. Couch later told the Inquiry he was there as a welfare officer, yet also claimed he didn’t interact with Lambert at all, not even to speak.

Docker says leaving John Player Special cigarette packets in the flat, the kind that had been used in the incendiary devices, was a deliberate ploy to provide a plausible reason as to why Lambert might be arrested. However, the search team didn’t spot these.

Docker says that ‘as far as I know’ the search was carried out normally, and none of the search team knew that Lambert was an undercover officer. Yet Couch, as part of the SDS backroom support team when Lambert was first deployed, will obviously have known him very well.

Barr points out that the court was misled when this search warrant was obtained. Docker says ‘I don’t see this as misleading a court at all’ but blames his senior officers for any failings anyway.

CCTV VIDEO DISAPPEARING

A security CCTV video tape was seized from the Harrow branch of Debenhams in July 1987. This would have shown the person who planted the incendiary device which, it’s abundantly clear, was Bob Lambert.

As James Wood KC has previously told the Inquiry:

‘CCTV from the Harrow store was recorded as having been obtained by police. The original exhibits officer has a clear recollection of Special Branch officers attending and taking custody of the exhibits in the case. After this point the CCTV appears to have gone missing.’

Docker dismisses this as ‘absolute rubbish’.

Police records show the tape was later destroyed without being watched.

‘I have no knowledge at all. It’s nothing we as SDS officers would’ve been involved in.’

Docker remains unconvinced that Lambert did anything wrong, or acted as an agent provocateur.

‘I trusted him. I knew what he was doing. He. Knew. Where. To. Draw. The. Line.’

This stands in stark contrast to his countless claims that he didn’t know what Lambert was doing and never asked. It’s also undermined by the fact that Lambert deceived four women into relationships which, even by Docker’s standards, is well on the far side of the line.

MISLEADING THE COURT

Docker says he appreciated the work that Lambert was doing undercover. He agrees that he wanted to protect the identity of such spycops and so wouldn’t have disclosed their status to the courts. This is withholding evidence, meaning any resulting convictions are a miscarriage of justice. Docker says no thought was given to that fact.

He says that he didn’t have anything to do with the Debenhams trial either – this would have been a matter for C Squad to liaise with the Anti-Terrorist Branch. He concedes that Lambert’s identity and role were not revealed in court. To reveal them would have shown him as an agent provocateur, resulting in his dismissal and a lot of blame falling on Docker and other managers. But to not reveal it meant the court was not dealing with the facts of the case.

Q: The court was misled?

Docker: If you want to put it like that, yes.

Barr immediately brought out a Home Office Circular of 1969 [MPS-0727104]:

‘The police must never commit themselves to a course which, whether to protect an informant or otherwise, will constrain them to mislead a court.’

Docker only concedes that ‘maybe’ the court should have been told that Lambert was an undercover officer, and absolutely denies that any of this was his responsibility.

ANY MEANS NECESSARY

Barr suggests that an alternative course of action could have been to advise Lambert not to become so involved, and thus avoid the need for any disclosure. But the SDS wanted the reports, Docker’s superiors expected them, and they thought nobody would ever check up on them, so there was a strong incentive to commit crime and mislead courts if it got the right results. The ends justified the means.

Docker: He produced the intelligence always under the instruction that he was not to become personally involved. I can’t take it any further than that because I never had any admission from him of any criminality. But he provided the intelligence.

Q: Isn’t that washing your hands – forgive me for putting it so bluntly – of the dilemma that Bob Lambert was in, tasked to infiltrate the Animal Liberation Front without getting too involved?

Docker: Well no, he knew what he was doing, and quite frankly, he produced the information that we needed.

Barr asks Docker if Bob Lambert was involved in any way with the other ‘improvised incendiary device’ attacks that took place in central London in November 1987.

We’re shown several related documents. There’s a briefing note about incendiary device attacks on Debenhams and C&A on Oxford Street in November 1987 [MPS-0748814]. Then a report about attacks on 12 November on Oxford Street department stores DH Evans and Selfridges [MPS-0748795]. Then a spycops report on both [MPS-0740492].

It’s reported that the devices used may have been manufactured outside of London. Docker says with absolute certainty that he is sure that Lambert was not involved at all:

‘He was a highly experienced undercover officer. He knew the limits of his deployment. And I do not think he would’ve compromised himself by putting himself in a position where he had to commit a criminal offence such as this.’

Somehow, he kept a straight face.

A device was left in DH Evans the following summer, in August 1988, but failed to ignite. Docker rejects the suggestion that this was planted in an attempt to bolster Lambert’s cover.

Docker is asked about Bob Lambert’s exfiltration. He says he left the unit before Lambert, but then admits that the exit strategy was already underway while he was still managing the SDS.

Part of Lambert’s plan involved making people think that the police were after him. Docker says:

‘I had no part in formulating or actioning that strategy’

He claims that it’s yet another key part of Lambert’s deployment that they never spoke about. One has to wonder what he ever did see himself as responsible for, and what he ever did speak to Lambert about.

Barr points out that Lambert’s exit strategy was related to his involvement in an ALF cell. Pretending the police were after you would not have worked for someone who wasn’t thought to be involved in serious crime. Docker doesn’t really provide any answers to this.

SDS Culture, Methods and Activity

HELEN STEEL

Docker is asked about Helen Steel, a London Greenpeace activist who was deceived into a long-term relationship by HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’. He remembers her name, and that she was a ‘very committed activist’. He read spycops reports about her. He admits he got this impression from Lambert’s reports.

Barr displays two reports from 1988. One, by Lambert [MPS-0740518], claims that Helen Steel attended a meeting in a London pub on 13 August. The other, by John Dines [MPS-0744064], says that Steel spent that same weekend in Yorkshire, protesting about grouse-shooting. Docker has signed off on both reports.

Did he not notice that these reports put her in two completely different places at the same time? How closely did he scrutinise Lambert’s reports?

Docker insists that he would check them for grammar, but admits that he didn’t pay ‘great attention’ to the actual content of spycops’ reports.

‘I had so many coming across my desk’.

With around a dozen officers reporting twice a week, that’s 24 reports in total, probably averaging around five paragraphs each. It’s no Herculean workload.

Barr points out that an unscrupulous officer could just lie in their reports and this would never be picked up on. Docker says he was able to ‘trust’ his officers.

This directly contradicts his assertions that there was no point in asking spycops difficult questions because they would only lie.

Steel has highlighted the way that Lambert seems to have frequently substituted activists’ names into his reports to cover for things he did himself. Docker says this would have been unacceptable. He adds that he was not responsible for fact-checking the intelligence reports (in fact, it appears that no one was), so he wasn’t in a position to argue with the spycops officer about what they wrote.

Docker says he has no memory of talking to John Dines about getting close to Helen Steel. He says he doesn’t know if Bob Lambert’s exaggerated reporting of Steel had made her seem more of a lynch-pin in activist circles and thus influenced Dines’ targeting of her. He may have discussed it, but can’t remember.

INTEGRATION WITHIN SPECIAL BRANCH

Docker says he worked closely with the other SDS office staff. He did most of the liaison upwards, with more senior officers, and would be the Acting Chief Inspector on occasion. He was in contact with his Chief Super ‘almost every day’, saying it was a short walk to Scotland Yard. He often saw other Special Branch squad chiefs there. He confirms that they all knew about the SDS and its capabilities, even if they weren’t fully aware of how they operated.

By this time, many Special Branch officers had been involved with the SDS and so knew about it. There were around 400 people within Special Branch at this time.

HN109

HN109 joined the SDS as a Detective Inspector, having previously served as an undercover officer himself in the 1970s.

‘He didn’t suffer fools gladly’

HN109’s prior experience undercover brought advantages; he understood the unique stresses and strains of the work. Asked what the disadvantages of employing someone with this experience were, Docker says he might have understood what the spycops really got up to in the field.

This is a further admission that the officers were not candid with their superiors and were commonly engaged in deeds that would be disapproved of.

Docker insists that the spycops of the day wouldn’t necessarily have shared everything with HN109 as their manager either.

HOME OFFICE APPROVAL REQUIRED

The SDS was directly funded by the Home Office from its formation in 1968 until just after Docker left. Permission to continue was granted annually. The unit would send an Annual Report and ask for renewal.

Docker is sure that he had no contact with the Home Office at all while at the SDS.

We next see a Security Service document [UCPI0000022283] that records Commander Phelan’s concerns about the possibility of the Home Office or Cabinet Office examining more closely the ‘nature of SDS sources’. It mentions a spycops officer’s cover may have been compromised by a colleague with a grudge, and that the Home Office might pose awkward questions about the SDS.

Docker is asked if he remembers these concerns about ‘awkward questions’. He says that the way he reads this document, the Security Service is offering some kind of solution to this but Phelan is unwilling to accept it.

He says that officers had been compromised since the formation of the SDS. He seems reluctant to accept that there was much real risk of the unit being closed down – unless there were ‘extreme’ circumstances.

He points out that the Home Office was sent the SDS Annual Reports every year. Though, as we’ve seen, these were often filled with exaggeration and lies to please the recipients.

EXTREMIST ACTIVITY: PRINTING PLACARDS

In February 1988, Docker wrote a report on the changing nature of ‘extremist activity’ and demonstrations in London [MPS-0730295]. In it, he talks a lot about his favourite bugbear, the Socialist Workers Party.

The Inquiry has already established that the SWP was very heavily infiltrated. Despite much of their activity being selling newspapers and printing placards for ordinary lawful demonstrations, and firmly disavowing violence (members who advocated it were expelled), it was nonetheless the main focus of the SDS.

Docker’s 1988 report talks about how, as Thatcherism bit harder into the fabric of society, more ordinary people are angry. Despite this change, he felt the SDS was still valuable in monitoring ‘extremists’ like the SWP and that, in turn, helped policing.

The Inquiry asked him if this meant the SDS had less purpose:

Q: Did anybody tell you that it was useful to understand the changing nature of demonstrations and to be reassured that the SDS could still provide useful public order intelligence?’

Docker: The only feedback I probably would’ve got is that the Home Office have agreed to another 12 months. That’s about it.’

MULTIPLE FAKE IDENTITIES

Barr asked if there was a limit to how many identities an undercover should use. Docker insists that they were instructed to pick one and stick to it. Asked what would happen if there was an expectation within the group they infiltrated that they should employ a false name in case of arrest, Docker says he doesn’t know.

We then see a file on HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’ [MPS-0746348], which includes a standard personnel record. Somebody has added a handwritten note:

‘On arrest will use one of his three names as surname’

That makes it clear that the police knew that Dines had an alternative surname, not just his official cover surname, ‘Barker’.

In his witness statement to the Inquiry, Dines has said that having this second fake identity ‘would have been considered a mark of credibility’ amongst his target group. He’s said that he knows that his second fake identity, ‘Wayne Cadogan’, had a driving licence in June 1988, when Docker worked in the SDS office.

Docker denies knowing about this, and insists that the spycops only had one false identity and he wouldn’t have allowed them to have more. He says if he’d known about this Dines would have been investigated, and he’d probably have taken it higher up.

REPORTING ON SEXUALITY

We then see a report from 17 June 1988 [MPS-0740559], about a ‘schoolgirl’ of 16, who is said to be ‘developing into a highly active animal rights campaigner’. Why collect information about her? Docker said this would have been recorded and sent to Special Branch’s C Squad, which monitored political activists.

The report includes information about this girl and her mother, and the sexual relationships the girl has. Docker is only willing to admit that this is ‘possibly’ not relevant to the question of subversion.

The spycops report goes on that the 16-year-old schoolgirl had ‘affairs’ with her lesbian friends. Docker says there were no guidelines on reporting on the sexual activity of children. He claims spycops didn’t have any interest in it. But adds that it was important to have the details on file in case she ever became an active campaigner.

He says they never scrutinised reports or removed anything from spycops intelligence. Even the sex lives of 16-year-old schoolgirls. The spycops report goes on to say that the girl was involved in various activities, but there is nothing about subversion or public order.

Docker attempts to somehow justify spying on her sex life by pointing out she was a member of a local hunt sabs group. He considers the collection and forwarding of such personal information about someone to be the ‘normal course of events’.

In his witness statement to the Inquiry [MPS-0749045], Docker suggested that collecting info about sexual orientation might be useful for the purpose of turning an activist into a police informant, i.e. that people in the closet could be blackmailed into betraying their friends.

He claims not to know much more – as he didn’t recruit informers himself – and claims this information was ‘not actively sought’, just ‘forwarded in the normal way’.

SEXIST REPORTING

Another woman activist is described as ‘attractive’ and it’s reported that she’s popular amongst animal rights activists. Docker has no problems with this.

Can he tell us more about the atmosphere in the spycops unit? Was there sexual banter?

‘There probably was to be perfectly honest. Within the office environment. I don’t know, I can’t recall anything.’

He claims they were ‘too busy’ to ever share any sexual jokes though, and says he doubts they ever discussed women activists.

Docker explained that, while spycops were not actively encouraged to use subjective terms like ‘very attractive’ in their reports, they were nonetheless permitted to include them if they wanted.

Addressing this in his statement, he wrote that because most of the intelligence community were men, if there was a woman who was very attractive it would have been commented on. Docker suggests there was nothing unusual in describing women in this way.

‘The standards of the day in the 1980s are totally different from those of today. And we had a much more, shall we say, male culture then, if I can put it that way. To put a comment in like this, to me, was acceptable’

Barr says if it’s on paper, then it would surely be said out loud too. Docker absurdly rejects this:

Q: Do you not recall anyone ever remarking upon whether female activists were attractive or otherwise?

Docker: No.

Q: In this male environment?

Docker: No.

Q: Applying 1980s standards?

Docker: No.

Q: Are you sure about that?

Docker: I am.

So, yet another officer who reckons the squad were respectful men who mysteriously put judgemental bigotry in official reports despite never saying anything of the kind out loud. He’s plainly lying again.

We hear about some of the spycops ‘jokes’, which Docker is sure spycops were always too busy to ever tell. Papers from Operation Sparkler, the recent police investigation into Lambert’s incendiary device [MPS-0737160], report that SDS manager HN109 had told them:

‘there had been jokes made about high standards of intelligence being gained from ‘horizontal politics’… The other standing joke was that [a woman activist] was not very attractive.’

Docker responds that:

‘I do not have perfect recall and I do not remember this’

When pushed, he concedes that HN109 has no reason to be making it up. As for whether it would be particularly hurtful for the woman concerned to hear about these degrading comments, he agrees:

‘It probably would be for the lady, yes.’

Relationships

Docker is next asked about the two occasions that HN12 ‘Mike Hartley’ is said to have had sexual relations with members of the public while undercover. He says he can’t comment:

‘I didn’t have any supervision over him’.

MIKE CHITTY & LIZZIE

Spycop HN11 Mike Chitty ‘Mike Blake’ undercover in the 1980s

In his witness statement, Docker has mentioned hearing something about HN11 Mike Chitty ‘Mike Blake’. He explains that he heard that Chitty was still associating with activists he’d met during his deployment, and denies hearing anything about a relationship with a woman.

Barr asks if he heard about his relationship with a woman who is known as ‘Lizzie’? Docker can’t tell us when he heard about this.

We see a 2 December 1986 report [MPS-0747694] about ‘Lizzie’, an animal rights activist, who is said to be buying a flat with her (uniform) ‘policeman boyfriend’. According to the report, animal rights campaigner Robin Lane and his girlfriend socialise there with her.

Did Docker know that Chitty spent time with this couple and ‘Lizzie’? Did he ever have any inkling about Chitty’s relationship with her?

Docker says this was near the end of Chitty’s spycops deployment, and in any case, he wasn’t an easy man to talk to, so no.

BOB LAMBERT & ‘JACQUI’

Did Chief Inspector HN115 Tony Wait talk to you about Bob Lambert getting ‘a girl in trouble’, that is, having a son with a woman known as ‘Jacqui’? Docker flatly denies it.

‘I heard nothing from Tony Wait on that and in fact when I did hear about it I was absolutely horrified.’

He claims not to have learnt about this until long after he’d left the SDS.

Did this mean Lambert was left to handle this situation on his own? Docker insists that Lambert never spoke to the spycops managers about it. This contradicts Lambert’s testimony.

What would Docker have done about telling Jacqui? He says that would have been a matter for more senior officers to deal with.

Lambert made frequent trips to Dagenham to see Jacqui and his son. Would the managers have noticed a pattern of this kind?

‘Very unlikely. Unless he was claiming expenses for travelling, something like that, which would show that sort of pattern.’

Would it not have been a good idea to keep an eye on the spycops expenses claims? Docker once again passes responsibility along the command chain:

‘I’m not sure we’d have had the time to indulge in that type of in-depth analysis. The sergeants in the office dealt with the expenses a lot of the time. I did not concern myself at my level with their expenses claims unless there was a problem.’

He denies knowing that Lambert was making regular maintenance payments to Jacqui. Was this money paid out of expenses claims? Docker says he can’t answer that, as the spycops expenses were paid in cash.

Lambert has said Jacqui was with a new partner who wanted to adopt his son, but this has been refuted – she didn’t meet the new partner until after Lambert’s deployment had ended. Docker can’t recall any talk about a child being adopted.

He denies seeing Lambert in any surveillance photos, or any mention of him in anyone else’s reports.

Barr asks next about ‘RLC’. Docker denies knowing about Lambert’s sexual relationship with her as well.

BOB LAMBERT & BELINDA HARVEY

Barr asks next about Belinda Harvey. Docker denies knowing about Lambert’s sexual relationship with her. Lambert spent a lot of time at Belinda’s home.

Docker says he didn’t know where his spycops were staying overnight and there would be no point asking as they’d be likely to lie to cover up prohibited behaviour.

Bob Lambert and Belinda Harvey by a lake, 1987 or 1988

The ease and frequency with which he uses that explanation fatally undermines the unit’s credibility in a way that Docker does not appear to be aware of. It admits that the spycops did not follow their own rules, and that the supposed ‘tight unit’ full of trust was actually a bunch of dishonest chancers who had no real respect for each other.

If it’s true, then he’s admitting to his role being ineffectual and pointless. If it’s not true, then Docker is at the heart of a vast counter-democratic conspiracy to violate citizens. No wonder he opts for the former.

He denies knowing that Lambert moved in to live with Belinda in a tower block in Hackney. Barr reads an extract from Belinda’s account of discovering that the police had raided that flat, published in the book Deep Deception. She describes the police holding up a pair of her shoes and being told they were hers.

Belinda also wrote about this in her witness statement to the inquiry (still not published by the Inquiry at the time of writing, despite her giving evidence back in November 2024!).

This raid of Belinda’s flat seems to have been arranged by Lambert to make his exfiltration story sound more credible. Docker denies knowing anything about it.

He says it sounds like it was done by the Anti-Terrorist Branch, not Special Branch. He agrees that he would have been informed if a raid had been planned. This took place in November 1988, the same month that Docker left the spycops unit. ‘I can’t help you,’ he repeats.

IGNORANT OF RELATIONSHIPS

Docker has said that he knew nothing about Lambert’s sexual activity, and his deception of four different women, even though it happened on his watch. Does he find it surprising that this happened without his knowledge?

‘I’m not surprised. Because it is very, very difficult to keep effective control over an SDS officer, and they are recruited for their intelligence, their work, their ability to work unsupervised.’

And, of course, their skill at misleading and lying.

He adds that if he had challenged Lambert about it, Lambert would only have lied to him anyway.

It’s amazing that Docker has such a solid presumption that Lambert would have lied about important aspects of his deployment, yet at the same time says Lambert was a great officer who he totally trusted to act with integrity.

When it was suggested that he did nothing to prevent undercover officers under his command deceiving women into sexual relationships because he thought it was futile to try, Docker began by disagreeing and ended up agreeing, apparently without realising.

Docker: No, I disagree with what you’ve said there. You started off by saying words to the effect that I did nothing to prevent it. There obviously would’ve been, at the recruitment process, basically telling them that they were not to indulge in sexual relationships. How and when that would’ve occurred, I can’t remember now. But the point I’m making is that to have challenged the officer, when he is an officer in the field like that, would have not have achieved anything because it would simply be denied.

Q: Subject to the evidence you’ve just given about a warning at the start, at the recruitment stage, did you do anything else to prevent undercover officers under your command entering into sexual relations with members of the public in their undercover identities?

Docker: No.

COMMENDATION THEN, CONDEMNATION NOW

Barr asks Docker if he still thinks that Bob Lambert deserves his commendation. Docker says this police award was based on his work, and his penetration of ‘an extremely disruptive extremist group’. He is adamant that he would still choose to award it now.

Barr asks if this diminishes the gravity of Lambert’s misconduct. Docker insists this is not the case. He would still give him the commendation, and separate it from his sexual misconduct.

Barr next reads from the Met’s apology for this misconduct made at the start of Tranche 2 of the Inquiry. It cites failings of SDS management, the lack of robust oversight and action, including disciplinary measures.

Docker accepts the apology’s intent, but doesn’t accept all of this criticism.

‘We are applying, as I said before, perhaps the standards of today to what occurred in the 1980s.’

He talks about how the SDS faced ‘unique’ problems. The spycops were given a great deal of personal discretion when they were out in the field. Introducing such ‘robust oversight’ would have required significant planning and:

‘may have disrupted in some way the whole focus of an SDS operation.’

Docker says he cannot fully support the words of the Commissioner, and insists that ‘we did the best we could at the time’. He claims that the spycops provided ‘useful and timely’ information which saved police resources.

‘Where do you draw a line? Which is a very, very difficult line to draw.’

He believes that some of the recommendations he made at the end of his time in the SDS to ‘enhance and refine’ the unit were taken up after he left. But he says the more control the managers exercised over the spycops, the more the quality of their intelligence might be affected.

This appears to be an outright admission that the SDS obtained intelligence by nefarious means, and that managers would not seek prevent abuses because that would damage the ‘quality’ of the intelligence.

SENIOR OFFICERS AS INSURANCE

We are shown the SDS Annual Report 1987 [MPS-0728976], and the section on the visit to the SDS safe-house by two very senior Met officers (the Assistant Commissioner Special Operations, John Dellow, and the Deputy Assistant Commissioner Special Branch, Simon Crawshaw).

Docker starts saying that ‘this was before my time,’ but then has to accept that it wasn’t and apologises.

Letter from Assistant Commissioner Hugh Annesley to Eric Docker thanking him for introducing him to all the spycops – quite an achievement given that Docker now claims he didn’t really know what any of the officers were up to.

Another document [MPS-0730311] records a similar visit by Hugh Annesley, the Assistant Commissioner Special Operations, in March 1988. He was to be accompanied to the spycops safe-house by Docker.

Afterwards, Assistant Commissioner Annesley wrote to Docker to personally thank him for facilitating the meeting and going to lunch together afterwards [MPS-0730296].

Docker actually admits to remembering this one. He says he prepared a briefing to explain which groups each officer infiltrated. It was his understanding that it was the Assistant Commissioner Special Operations who wrote to the Home Office every year to ask for renewal of the SDS’s funding.

Annesley met and spoke to each of the spycops. Asked if he spoke to Annesley about training, Docker answers with a blunt ‘no’ and looks at Barr as if is he is stupid for asking.

In his witness statement to the Inquiry, Docker has referred to such visits as an ‘insurance policy’ for the SDS.

Barr suggests – after apologising in advance for his ‘vulgar’ language – that this was in case ‘the shit hit the fan’ at some future point.

Docker confirms it. These interactions ensured that the senior officers couldn’t deny knowing about the spycops unit, if its existence ever became public knowledge and faced the outcry that those on the inside had always anticipated.

This was, nonetheless, exactly the Met’s initial response when the spycops scandal broke in 2010. They told us Mark Kennedy was a rogue officer, but then we proved there were dozens like him. Then they told us the SDS was a rogue unit, so secret that most of Special Branch wouldn’t have known of its existence.

The performance at the Inquiry is further damage limitation. The Met is condemning the abuses as if senior officers hadn’t known full well for decades, and liars like Docker are claiming ignorance so the specific blame rises no higher than is absolutely necessary.

Docker says he believed Annesley was impressed by the ‘calibre’ of the spycops he met during his visit. He got a letter from Annesley afterwards and he was fully supportive, saying he enjoyed the visit.

DISHONESTY

How does Docker account for his high opinion of the spycops’ ‘calibre’ compared to his low opinion of their honesty?

For Docker to be so sure that they’d have lied if asked, he surely has to have had that view of their probity at the time. However, he doesn’t explain why he’s so certain that they’d have lied to him and other managers if he asked about relationships or criminal activity.

Barr checks with Docker that spycops were expected to call the SDS office by phone every day. Twice a day, Docker specifies. This was to ensure they were safe and well – ‘still alive and still working’ he says.

He denies that there was any requirement for them to tell the office where they were or where they intended to sleep. Docker says recording this would have been too much work for the office staff.

He imagines that if he’d asked them, the spycops would have been indignant and questioned why they were being asked to provide this information. Barr points out that knowing where they are is surely essential to securing their safety. Docker has no response to this.

Stefan Scutt

We then examined the peculiar case of a problem officer, HN95 Stefan Scutt ‘Stefan Wesalowski’.

Scutt had travelled to Skegness to attend the 1987 Socialist Workers Party annual conference, and details of all attendees were supplied to the Security Service [UCPI0000029278]. Docker admits that such SDS intelligence was probably more useful to the Security Service, who had a national remit, than it was to the Met.

Did Stefan Scutt put himself at risk to obtain this information? Docker says he doubts it, based on what he knows of this officer.

Asked if the Socialist Workers Party were ever disorderly on demonstrations, Docker speaks through gritted teeth about how the SWP tried to stir up trouble:

‘You’ve only got to look at placards from demonstrations, you can even see them now, and it will have Socialist Workers Party printed on the bottom of them.’

Barr asks Docker if he ever saw SWP members being disorderly.

‘Not particularly’

IDEAL OFFICER

We next see Scutt’s AQR (personnel review) dated 23 April 1987 [MPS-0748500]. The ‘other comments’ section has been filled in by Docker.

Q: It’s a glowing report, isn’t it?

Docker: It is.