In July 2014, police admitted there was proof that undercover officers from the Special Demonstration Squad had spied on 18 grieving groups of families and friends seeking justice for their loved ones. They did not publish a list, but said that ‘the majority’ were black. This is institutional racism.

In July 2014, police admitted there was proof that undercover officers from the Special Demonstration Squad had spied on 18 grieving groups of families and friends seeking justice for their loved ones. They did not publish a list, but said that ‘the majority’ were black. This is institutional racism.

These people were campaigning for their truth. They only wanted to know what really happened, and for people to see the police for what they actually are and what they had actually done. But people of colour self-organising is perceived as a threat in itself. This was compounded by the threat of embarrassment to the police, the brand damage that would occur if these campaigns became popular.

The combined threat was enough to have them actively befriended by paid betrayers. Officers took active, pivotal roles in campaigns. Undercover officer Mark Jenner was a long-term activist at the Colin Roach Centre, chairing meetings and editing newsletters.

Just as the infiltration of protest groups shows the counter-democratic remit of the spycops, so their infiltration of justice campaigns over a period of 26 years proves a key part of their purpose was to take an active role in obstructing justice.

The resources that should have established the truth and brought the guilty to justice were instead spent on undermining the grieving loved ones.

Which Campaigns Were Spied On?

But which campaigns were known to have been spied on? The Guardian reported that the police’s 2014 list of 18 included:

1. Harry Stanley

2. Wayne Douglas

3. Michael Menson

4. Jean Charles de Menezes

5. Cherry Groce

6. Stephen Lawrence

7. Ricky Reel

Other reports from the time added:

8. Rolan Adams

9. Joy Gardner

The Undercover Policing Inquiry later confirmed the list included:

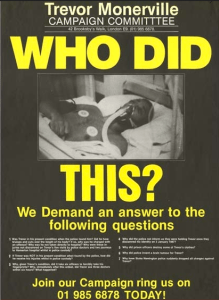

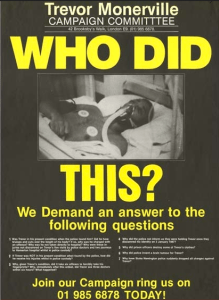

10. Trevor Monerville

Beyond the ten we can be sure of, it’s notable that the families of Roger Sylvester and Blair Peach are core participants at the inquiry.

Additionally, whistleblower SDS officer Peter Francis has cited the ‘moral low point’ of his time undercover as his infiltration of the Brian Douglas campaign.

It’s not clear if the Brian Douglas, Roger Sylvester or Blair Peach campaigns are on the list of 18. These are just the named ones they have admitted to spying on. There are eight unnamed and there must surely be many more besides.

We can be confident that police units devoted to secrecy – who institutionally avoided documentation and have shredded incriminating files since the Inquiry was announced – will have spied on many more justice campaigns than there is proof of.

How Many More?

We recently learned of two SDS officers from the early 1970s. Alex Sloan infiltrated the Irish National Liberation Solidarity Front at a time when they were in a demonstration against the police’s killing of Stephen McCarthy.

John Clinton infiltrated the International Socialists (forerunner of the Socialist Workers Party), 1971-74. Was he at the International Socialists-supported demonstration in June 1974 where police killed Kevin Gately outside Conway Hall in London?

There are so many other people killed by police in London whose justice campaigns seem highly likely to have been spied upon. These include Winston Rose, Cynthia Jarrett, Oluwashiji Lapite, David Ewin, Ibrahim Sey, Richard O’Brien, Sean Rigg, Derek Bennett, Azelle Rodney, Paul Coker, Frank Ogburu and Mark Duggan. There are also campaigns by loved ones of people who died in unexplained circumstances with police involvement, such as Nuur Saeed, Colin Roach, Daniel Morgan and Smiley Culture.

Additionally, there are organisations who are racial justice advocates and co-ordinate justice campaigns who were spied on in their own right. Several have already been given core participant status at the public inquiry, including the Broadwater Farm Defence Campaign, Hackney Community Defence Association, Youth Against Racism in Europe, Newham Monitoring Project and the Monitoring Group.

All these are just in the London area, and thus are likely targets for the Met’s spycops. There are many others beyond the capital such as Christopher Alder, Clinton McCrubin, James Ashley, Liddle Towers, Leon Patterson, Giles Freeman and Alton Manning. Then there are the victims of racist killings that were not properly investigated, leaving killers free to do it again.

As with learning the spycops’ names, we have only identified a fraction of the number of spied-upon justice campaigns. We have so much more to learn than the police and public inquiry have admitted to.

Here are brief details of the 13 people’s deaths whose campaigns police have confirmed they spied on.

The 13 Confirmed Campaigns

Wayne Douglas

In December 1995, Wayne was being questioned in Brixton police station. Police said he collapsed during questioning and died of heart failure. The inquest showed that Wayne, who suffered from heart disease, had been held face-down with his hands cuffed behind his back on four different occasions.

Though at the inquest the jury acknowledged police action caused Wayne’s death, by majority verdict they said it was accidental. The family’s appeal for a second inquest was refused with Lord Woolf saying:

‘little more could be achieved by subjecting all concerned to the considerable expense and stress of a further inquest.’

Wayne’s sister Lisa Douglas-Williams said:

‘We are particularly upset by the judge’s remarks about the expense of holding a further inquest. A proper verdict on my brother’s death is far more important than money.’

Michael Menson

Musician Michael Menson was racially abused and had his coat set on fire set on fire by three men in February 1997, who then went to get flammable liquid and returned to burn him more severely. In hospital, he told family and police he had been attacked. He died several days later from his injuries. Police treated it as suicide.

After two botched police investigations, the inquest verdict of unlawful killing forced a third which ended in three people being charged.

A three-year investigation for the police complaints authority by Cambridgeshire police found evidence of negligence and racism including an officer telling a pathologist:

‘I don’t know why they’re worried – this only concerns a fucking black schizophrenic.’

The CPS decided not to prosecute any officers.

Michael’s elder brother, Kwesi, said

‘I don’t have any doubt that had a white man been set on fire in a street in north London that there would have been an active and vigorous investigation’

Jean Charles de Menezes

On 22 July 2005, Jean Charles, a 27 year old electrician, lived in South London flats that were being watched by police trying to trace people responsible for failed bombings the day before.

As he left for work he was followed by police who, failing to comply with instructions to stop him entering the tube system, followed him into Stockwell station and executed him on the train.

Spurious details appeared in the press to make him appear deserving of his fate – he was in the country illegally, wearing a bulky jacket on a hot day, his clothing had wires coming out, he vaulted the station barrier and ignored police shouts to stop – all of which were found to be untrue.

His mother told the press

‘I want the policeman who did that punished. They ended not only my son’s life, but mine as well.’

Though the inquest uncovered a host of serious failures by police, and found the officer who shot Jean Charles did not tell the truth, no officer was charged.

The coroner had instructed the jury not to return a verdict of unlawful killing. The jury rejected the police account and returned an open verdict.

Cherry Groce

Dorothy ‘Cherry’ Groce was shot in the chest by police while they were searching her home in Brixton, south London, looking for her son Michael in September 1985. Anger erupted into rioting that evening.

Cherry survived the shooting but the bullet had passed through her spine, leaving her paralysed from the waist down. She reached a settlement with the police but they accepted no liability. Detective Inspector Douglas Lovelock was prosecuted for the shooting but acquitted.

Her son Lee Lawrence described the harassment that followed.

‘When I was in my teens I used to get picked up by the police for things I hadn’t done. They would tell me I fitted the description of someone who had just committed a crime and that sort of thing. Once when I was 17 I was put into a police cell. A police officer opened a flap in the cell door and said: “Are you Cherry Groce’s son?” When I replied that I was he said: “Pity she didn’t die”.’

Cherry died in 2011, and pathologists concluded the injuries from the shooting were causal. An inquest – for which the family were denied Legal Aid until a campaign got the decision overturned – lambasted police failings in the raid and arrogance in refusing to take responsibility afterward.

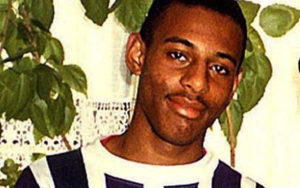

Stephen Lawrence

Eighteen year old Stephen Lawrence was murdered by a racist gang in Eltham, south London, in April 1993. The swathe of police failings meant that, although everyone knew who the killers were, none were prosecuted.

Five years later the Macpherson Inquiry examined the case and famously concluded that the Met were institutionally racist.

Rev David Cruise said the case showed that it was race, not behaviour, that defined treatment by the police.

‘The irony is that the Lawrences behaved exactly how every black family is supposed to behave. They were law-abiding, close, stable, relaxed and upwardly mobile.’

Stephen’s friend Duwayne Brooks, the main witness to the murder, was repeatedly prosecuted on trumped up charges that were thrown out of court.

Two of the five killers were finally convicted in 2012. Stephen’s mother Doreen responded

‘Now that we have some sort of justice I want people to think of Stephen other than as a black teenager murdered in a racist attack in south-east London in April 1993. I know that’s the fact, but I now want people to remember him as a bright young man who any parent of whatever background would have been proud of. He was a wonderful son and a shining example of what any parent would want in a child.’

Ricky Reel

Ricky was last seen in Kingston-Upon-Thames. He had been harassed by racists who chased him towards the river. His body was found downstream a week later on 21 October 1997.

When his parents reported him missing, the police officer mockingly suggested Ricky had run away to avoid an arranged marriage or because he was secretly gay. They have consistently refused to consider the death as foul play, let alone a racist murder. When Ricky’s clothes were returned to the family, his mother Sukhdev found a big rip in the shirt. Police accused her of making it.

A report by the Police Complaints Authority concluded there had been ‘weaknesses and flaws’ in the initial investigation and criticised three officers for neglect of duty. Sukhdev became an ardent fighter for justice.

‘I became a lawyer because it was my way of processing everything that had happened to me. I just kept seeing how a normal family like ourselves, not rich, can be turned upside down overnight. You can be completely normal and secure to completely vulnerable in a heartbeat and then you’re reliant on people like the police in authority to help you.’

Sukhdev Reel remains a committed and moving campaigner for justice for her son.

Rolan Adams

Fifteen year old Rolan was with his brother Nathan in February 1991 when they were attacked by a large racist gang. Telling Nathan to run, Rolan was chased, cornered and fatally stabbed in the neck.

Fifteen year old Rolan was with his brother Nathan in February 1991 when they were attacked by a large racist gang. Telling Nathan to run, Rolan was chased, cornered and fatally stabbed in the neck.

Though there were 15 attackers only one, Mark Thornburrow, was convicted of the killing. Four others were found guilty of public order offences and given 120 hours’ community service.

Two years later, Stephen Lawrence was murdered nearby. Two of the four convicted over Rolan’s death were named in the Macpherson report into Lawrence’s murder as individuals the police should interview.

Rolan’s father Richard Adams said:

‘There is no doubt that had Rolan’s murder been investigated properly, Stephen Lawrence may still have been alive today.’

Harry Stanley

Harry Stanley was a 46 year old painter and decorator, brought up in Glasgow but living in London all his adult life. In September 1999 he was returning home with a bag containing a table leg that had been repaired by his brother.

Police had received a call about “an Irishman with a gun wrapped in a bag”. Two armed officers challenged Harry from behind. As he turned to face them, they shot him dead at a distance of 15 feet.

The coroner only allowed a verdict of lawful killing or an open verdict, and the jury opted for the latter. Harry’s family managed to get a second inquest which returned a verdict of unlawful killing. The officers involved were suspended, but after more than a hundred of their colleagues handed in their firearms authorisation cards in protest, the suspensions were lifted.

Harry’s son Jason said

‘If this can happen to my dad, it can happen to anyone. It just proves that nobody is safe on the streets.’

In 2005 the High Court the High Court decided that there was insufficient evidence for the verdict of unlawful killing and reinstated the original verdict, with the judge saying a third inquest should not be allowed. The Stanley family said

‘families cannot have any confidence in the system. They feel they cannot get justice when a death in custody occurs’

Joy Gardner

Mature student Joy Gardner had her north London house raided by immigration officials in June 1993.

Mature student Joy Gardner had her north London house raided by immigration officials in June 1993.

When she resisted attempts to put her in a 4-inch wide restraint belt with attached handcuffs she was shackled, gagged, and 13 feet of adhesive tape was wrapped round her head. She rapidly suffered respiratory failure and died four days later without regaining consciousness.

Joy’s mother, Myrna Simpson, said the police were in denial about their racism.

‘[Met chief] Paul Condon said it was not about race. Well, I say, how many white women have they done that to? Look at [serial killer] Rose West and look at what she did. But they still treated her as a human being. They didn’t go into her house, truss her up and kill her. What they did to Joy was terrible, terrible. I just keep asking why? Why? Why?’

Three police officers were charged with manslaughter. Though four pathologists agreed on the cause of death, police – as they would do later with Ian Tomlinson – found one who would give an alternative cause. The suggestion that it was a head injury, rather than complete blockage of airways, that caused the lack of oxygen gave a grain of doubt and all three officers were acquitted.

The use of gags was banned shortly after, but no admission has ever been made that it was part of the cause of Joy’s death.

Special Demonstration Squad boss Bob Lambert oversaw the spying on Joy’s family campaign. At the time of her death, Joy was studying Media Studies at London Metropolitan University, which would later coincidentally employ Lambert as a lecturer.

Trevor Monerville

In January 1987, 19 year old Trevor Monerville was taken to the notorious Stoke Newington police station. Two days later his father John reported him missing and the police still didn’t say he was in custody.

In January 1987, 19 year old Trevor Monerville was taken to the notorious Stoke Newington police station. Two days later his father John reported him missing and the police still didn’t say he was in custody.

Trevor had been severely beaten, with extensive injuries to his face and brain which left him with permanent brain damage. Police had then taken him to hospital where he had to have emergency brain surgery.

The Police Complaints Authority refused to release the custody record, and Trevor’s doctors were told not to speak to the family’s lawyers.

Afterwards, Trevor was repeatedly arrested and charged for various offences, and was repeatedly acquitted.

Trevor was murdered in an apparent street robbery in 1994. Nobody was ever charged.

Trevor’s 73 year old grandmother was assaulted by police so badly that she eventually received £50,000 compensation.

In 2013, Trevor’s brother Joseph Burke-Monerville was shot in a case of mistaken identity. The three main suspects were so implicated that they were forced to attend the inquest and eventually charged only for the Crown Prosecution Service to offer no evidence on the day of the trial. In 2017 they lodged a 15-page complaint about police failings over the murder.

After more than 30 years fighting for justice, father John Burke-Monerville said

‘It would be a real joy to the family to have a conviction. Twice around and we have had no result whatsoever. We are in limbo, waiting.’

At Joseph’s inquest, the family wondered why Trevor hadn’t had one. Their lawyer discovered in August 2017 there had in fact been an inquest for Trevor but the family hadn’t been told about it.

Roger Sylvester

In January 1999, police were called as Roger Sylvester was outside his house and shouting. Thirty year old Roger had bipolar disorder and wasn’t himself that day. Eight police restrained him and took him away for detention under the Mental Health Act.

In January 1999, police were called as Roger Sylvester was outside his house and shouting. Thirty year old Roger had bipolar disorder and wasn’t himself that day. Eight police restrained him and took him away for detention under the Mental Health Act.

Though officers are trained not to restrain people face down, they did this with Roger. He suffered serious brain damage and cardiac arrest, and fell into a coma.

The Met’s press office issued a statement claiming that someone had called 999 and described Roger as acting in an ‘aggressive and vociferous manner’. They were later forced to admit this wasn’t true and apologise for it. Roger died eight days later without regaining consciousness.

Police coroner Freddy Patel told the media Roger was a crack user, something his family denied. Patel later performed the autopsy on Ian Tomlinson that favoured the police version of events and led to Tomlinson’s killer’s acquittal. In 2012 Patel was struck off by the General Medical Council who found that he was not only incompetent but also dishonest.

Though it took four years to get an inquest for Roger, it took the jury only two hours to reach a unanimous verdict of unlawful killing. The officers responsible for the killing had the verdict overturned on appeal.

Roger’s brother Bernard Renwick said

‘From day one we were told to expect openness, accountability and transparency. We merely wanted truth and where necessary justice. Instead we have had obstacles, delays, anguish, smoke and mirrors and ‘just-ice’. Where is the justice?’

Blair Peach

Teacher Blair Peach went on an Anti-Nazi League demonstration in Southall, South London on 23 April 1979. It was a few weeks ahead of the general election and the National Front were having an election meeting at the Town Hall.

Teacher Blair Peach went on an Anti-Nazi League demonstration in Southall, South London on 23 April 1979. It was a few weeks ahead of the general election and the National Front were having an election meeting at the Town Hall.

Having broken away from the main demonstration into a side street, Peach was confronted by a vanful of Special Patrol Group riot officers, one of whom fractured his skull with an unauthorised weapon. Eleven witnesses gave testimony.

The coroner dismissed the possibility of an officer killing Peach, discounted accounts from Sikh witnesses, and tried to prevent a jury being instated. A misadventure verdict was returned.

Crucially, the inquest ignored the report by Commander John Cass which found the SPG officers had a range of unauthorised weaponry and Nazi memorabilia. The officers refused to co-operate with the inquiries and many changed their appearance to impede witnesses ability to identify them. The Cass report was published 30 years later. It identifies ‘Officer E’ as ‘almost certainly’ being Peach’s killer.

Blair’s partner, Celia Stubbs, reflected on Blair and his measure of justice after so long.

‘He was a dedicated teacher, a committed trade unionist and anti-fascist. He was a good, funny and loving person to his family and friends. He was a socialist who believed passionately in fairness and equality.

‘He supported the Bengali community in their protests against the National Front selling their newspapers in Brick Lane, demonstrated outside a pub that would not serve black customers, and had been instrumental in getting the National Front headquarters closed in Shoreditch.

‘It was his socialist beliefs that took him to Southall, and it is amazing that he is remembered by so many people.’

Officer Alan Murray – who lied to investigators and refused to take part in identity parades at the time – has identified himself as the officer in question (though he denies killing Peach). Neither he, nor anyone else, has ever faced any charges.

Brian Douglas

Police stopped Brian Douglas while driving in May 1995. Witnesses say that PC Mark Tuffey used a then-new extendable baton to strike a downwards blow on Brian’s head. Tuffey said it was aimed at the upper arm but slid up over the shoulder.

Police stopped Brian Douglas while driving in May 1995. Witnesses say that PC Mark Tuffey used a then-new extendable baton to strike a downwards blow on Brian’s head. Tuffey said it was aimed at the upper arm but slid up over the shoulder.

Three pathologists later said Brian had received hard blows to the back of the head. Brian suffered massive and irreversible brain damage. Despite vomiting in his cell, he was left for 12 hours before finally being transferred to hospital where he died.

Brian’s brother Donald Douglas said

‘I fear that the numbers killed in police custody over recent years without redress may have helped to shape the attitude that informed those officers when they brought down that baton on my brother’s skull.’

The campaign was spied on by Special Demonstration Squad officer Peter Francis who has described his subsequent shame.

‘By me passing on all the campaign information – everything that the family was planning and organising through Youth Against Racism in Europe – I felt I was virtually reducing their chances of ever receiving any form of justice to zero. To this day, I personally feel that family has never had the justice they deserved.’

The recent

The recent  In July 2014, police admitted there was proof that undercover officers from the Special Demonstration Squad had spied on 18 grieving groups of families and friends seeking justice for their loved ones. They did not publish a list, but said that ‘the majority’ were black. This is institutional racism.

In July 2014, police admitted there was proof that undercover officers from the Special Demonstration Squad had spied on 18 grieving groups of families and friends seeking justice for their loved ones. They did not publish a list, but said that ‘the majority’ were black. This is institutional racism.

Fifteen year old Rolan was with his brother Nathan in February 1991 when they were attacked by a large racist gang. Telling Nathan to run, Rolan was chased, cornered and fatally stabbed in the neck.

Fifteen year old Rolan was with his brother Nathan in February 1991 when they were attacked by a large racist gang. Telling Nathan to run, Rolan was chased, cornered and fatally stabbed in the neck.

Mature student Joy Gardner had her north London house raided by immigration officials in June 1993.

Mature student Joy Gardner had her north London house raided by immigration officials in June 1993. In January 1987, 19 year old Trevor Monerville was taken to the notorious Stoke Newington police station. Two days later his father John reported him missing and the police still didn’t say he was in custody.

In January 1987, 19 year old Trevor Monerville was taken to the notorious Stoke Newington police station. Two days later his father John reported him missing and the police still didn’t say he was in custody. In January 1999, police were called as Roger Sylvester was outside his house and shouting. Thirty year old Roger had bipolar disorder and wasn’t himself that day. Eight police restrained him and took him away for detention under the Mental Health Act.

In January 1999, police were called as Roger Sylvester was outside his house and shouting. Thirty year old Roger had bipolar disorder and wasn’t himself that day. Eight police restrained him and took him away for detention under the Mental Health Act. Teacher Blair Peach went on an Anti-Nazi League demonstration in Southall, South London on 23 April 1979. It was a few weeks ahead of the general election and the National Front were having an election meeting at the Town Hall.

Teacher Blair Peach went on an Anti-Nazi League demonstration in Southall, South London on 23 April 1979. It was a few weeks ahead of the general election and the National Front were having an election meeting at the Town Hall. Police stopped Brian Douglas while driving in May 1995. Witnesses say that PC Mark Tuffey used a then-new extendable baton to strike a downwards blow on Brian’s head. Tuffey said it was aimed at the upper arm but slid up over the shoulder.

Police stopped Brian Douglas while driving in May 1995. Witnesses say that PC Mark Tuffey used a then-new extendable baton to strike a downwards blow on Brian’s head. Tuffey said it was aimed at the upper arm but slid up over the shoulder.

Storage facilities with most documents missing or misfiled, systems repeatedly described as ‘chaotic’ by the police themselves – internal documents reveal that the Met is having big problems sorting out its records management before it can even tell the Pitchford Inquiry what’s gone on.

Storage facilities with most documents missing or misfiled, systems repeatedly described as ‘chaotic’ by the police themselves – internal documents reveal that the Met is having big problems sorting out its records management before it can even tell the Pitchford Inquiry what’s gone on.