UCPI: Weekly Report 3: 16-19 November 2020

The third week of the Undercover Police Inquiry’s hearings brought revelations and frustrations.

The third week of the Undercover Police Inquiry’s hearings brought revelations and frustrations.

The former undercover officers of Britain’s secret police engaged in a parade of selective amnesia, admitting what their vintage documents confirmed, but not a lot more.

And yet, we also brought the murky world of the spycops further into focus, learning the names of another MP who was spied on and a senior officer who illegally colluded with industrial blacklisting, as well as catching the Inquiry itself covering up for a criminal spycop.

CELEBRITY GUERRILLA COVERAGE

The Inquiry still refuses to live-steam its hearings, only giving us a live transcript that can’t easily be paused or rewound – a challenge to stare at for hours on end.

The women from Police Spies Out of Lives, representing women deceived into relationships by spycops, took matters into their own hands with a live reading of the transcript on their YouTube channel.

They took this inspired idea a stage further later in the week, with actors Maxine Peake, Siobhán McSweeney, and Barnaby Taylor speaking the words of the spycop witnesses.

There is, of course, no reason why the Inquiry can’t provide us with an audio-stream of the hearings. It would be no different to the read-a-long in terms of security. It’s further evidence of the way the Inquiry regards victims of spycops as marginal and the wider public as an irrelevance.

OVERVIEW

In the last three weeks, the Inquiry hearings have focussed on the formation of what began as the ‘Special Operations Squad’ (SOS) in 1968, and the years leading up to its re-naming as the Special Demonstrations Squad (SDS) in 1972.

It has confirmed the names of more than 100 groups who weren’t previously known to have been spied on.

There’s no good reason why the list couldn’t have been published by the Inquiry before, allowing members of those groups to come forward with relevant testimony in time to contribute.

The movement against the war in Vietnam was the original target for this new method of deep surveillance, and during this period the spycops also reported on anarchist, socialist, communist, Irish and anti-racist groups.

‘THROWN IN’

One after another, the former spycops described:

- being asked to join the unit, rather than formally applying;

- receiving no formal training or briefings;

- being initially sent out without even a target group or movement, just to see what they could join;

- not being steered away from groups that were clearly no threat to anyone;

- no advice as to what information to report, just a vague indication that all information was good information;

- deployments lasting much longer than the 12 month maximum stipulated by SDS founder Conrad Dixon (unless something went wrong & it was ended early);

- no psychological care during or after deployment.

Spycop ‘Dick Epps’ said:

‘I was never sat down in a classroom or a training room and given a training manual, or training lectures… We were all, if you like, being thrown in to a maelstrom, and seeking to find some sense of what we were trying to do’

Rather than merely gathering information on public order issues, it is abundantly clear that spycops were foot-soldiers for the Security Service, and most SDS reports were copied to MI5. It’s also a fact that details of activists were illegally shared with employment blacklisting organisations.

This overlap has been starkly, if unwittingly, illustrated by spycops who flitted between the concepts of democracy, national security, government policy, and corporate convenience as if these were all one and the same.

The spycops talked about targeting groups who ‘want to overthrow our form of democracy’, yet they spied on numerous democratic organisations, including political parties whose very function was to participate in our form of democracy. They sent one officer after another into the anti-apartheid movement, whose sole objective was to help bring democracy to South Africa.

NO SET TARGET

Giving evidence, the spycops admitted very little beyond what their own vintage documents proved, unless it served to distance them from responsibility. Their denials were risibly implausible, claiming to be unable to recall some of the central campaigns they were spying on.

When forced to concede that many groups they spied on posed no threat to the public, they tried to defend their deployments by saying the innocent groups were allied with more dangerous ones who were the actual focus.

None of them could explain why they failed to join the supposed real targets, nor why they were reporting personal details of the people in any and every group they came across.

Epps claimed anarchists were always the likely cause of any public disorder, but when asked why he didn’t infiltrate them instead of peace campaigns, he said:

‘I don’t know that it ever occurred to me that that was a route that I might find useful. But some of them were, as I say, harebrained and a little overexcited at these moments, and I didn’t feel drawn to that sort of grouping.’

Epps infiltrated the International Marxist Group (IMG) because they ‘took part in every demonstration going’. He was instructed by his managers to make a copy of the IMG’s office keys. He admitted he didn’t remember any IMG members being violent or disorderly at demonstrations, but claimed ‘they were much busier than other groups’ – as justification in itself.

OFFICER HN340 ‘ANDY BAILEY’

Officer HN340, ‘Andy Bailey’ (or ‘Alan Nixon‘), was, like Epps, deployed between 1969 and 1972. He said a lack of instruction was a continual feature of his work, and that he just made up his methods and activities. He presumed he was doing the right thing because his managers never told him otherwise.

Bailey joined a tiny left-wing discussion group, the North London Red Circle. In his written statement he described the Red Circle as ‘a talking shop’, saying:

‘It did support a revolutionary agenda and was subversive to the extent that it advanced the overthrow of the established political system in the UK, albeit never took any concrete steps… violence would have been the last thing on many of their minds’.

He said it was a ‘recruiting ground for the International Marxist Group’, with an implication that the IMG was in itself a serious threat to public safety even though, as we heard from Dick Epps, other officers knew that wasn’t the case and they’d only spied on the IMG because they, in turn, was supposed to be adjacent to the real targets.

IRISH ISSUES

Bailey also infiltrated the Irish Civil Rights Solidarity Campaign (ICRSC). Irish republican politics was a popular cause with the left at the time. As in the early years of the Troubles, Republicans were only attacking military targets in Northern Ireland it was, for many, a cause with little moral dilemma.

In October 1970, Bailey also attended the founding conference of the Irish Solidarity Campaign (ISC) in Birmingham. For an SDS officer to go to another constabulary’s jurisdiction, the unit must have either secured the permission of the local police, in which case they were complicit in what the spycops did, or else it was done without local approval, which is a serious breach of police protocol.

That Irish Solidarity Campaign founding conference was also attended by Bailey’s colleague, SDS officer HN68 ‘Sean Lynch’, whose deployment focused on Irish solidarity groups. A report was produced afterwards, with both their names attached to it, which contained a long list of all the groups and ‘fraternal delegates’ who attended the conference.

He explained:

‘They were there and so I reported it; it was then down to the back office to do their filtering, vetting, or whatever you call it’

The report was sent to both MI5 and the Home Office. The Met’s Deputy Assistant Commissioner commended the ‘first class work’ and asked that the officers be praised.

It will have been obvious to that senior officer that the depth of knowledge in the report can only have come from sustained infiltration.

It is already clear – and getting even clearer – that the SDS’s work was known and approved of at the highest levels of the Met, as well as its paymasters in the Home Office. There is, therefore, no way to sustain the claim that the SDS was a rogue unit, so secret that nobody outside really knew what was going on.

Bailey could not recall ISC members ever taking part in any acts of violence, nor any public disorder at any demonstrations organised by the ISC:

‘I’m sure something like that would have stuck in my memory and it definitely doesn’t.’

ANOTHER MP SPIED ON

Bailey’s reports would specifically mention whether or not events were attended by Bernadette Devlin, a young independent Irish republican MP.

According to Bailey:

‘if she was known to be going to attend any meeting or demonstration or whatever, then of course that would increase the likelihood of more people arriving at the demonstration’.

Devlin joins the growing list of MPs confirmed as having been spied on by the SDS, the unit that was supposedly formed to frustrate those who would overthrow parliamentary democracy.

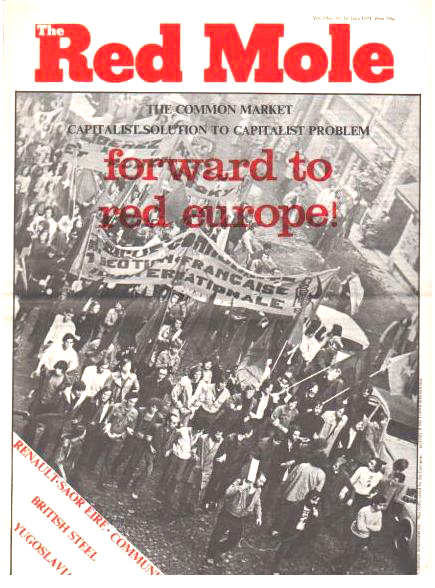

SPYCOPS ABROAD

Bailey’s managers had instructed him not to join the International Marxist Group because it was ‘recognised as more of a political party’. This doesn’t tally with the fact that his contemporary, ‘Doug Edwards’, was not merely a member of the Independent Labour Party but the Tower Hamlets branch treasurer.

His managers did, however, instruct him to attend the Conference for a Red Europe in Brussels in November 1970, organised by the Fourth International (of which the IMG was a part).

His managers did, however, instruct him to attend the Conference for a Red Europe in Brussels in November 1970, organised by the Fourth International (of which the IMG was a part).

As with the ISC conference in Birmingham a month earlier, Bailey says there was no direct contact between him and the other spycop who attended. That other officer was officer HN326, ‘Doug Edwards’, who complained about the trip in his evidence to the Inquiry.

This is the earliest known instance of spycops travelling abroad. It’s unclear whether the SDS followed protocol and got permission from their counterparts in Belgium (and any countries they passed through).

It is yet another example of spycops’ being engaged from the start in an activity that has been explained away as a later aberration.

TRADE UNIONIST DAVE SMITH

Blacklisted trade unionist Dave Smith was initially forbidden to deliver his opening statement to the Inquiry, as it mentioned the real name of spycop ‘Carlo Neri’ – which is Carlo Soracchi. The Inquiry insisted on nobody saying the name Soracchi out loud, even though it has been in the public domain for 18 months.

Dave Smith

Smith spoke on behalf of the Blacklist Support Group (BSG), representing union members who were unlawfully blacklisted by major construction firms.

When the BSG first spoke about being blacklisted for union activities, they were ridiculed as conspiracy theorists. But it’s conspiracy fact – and it involves the collusion of the police and the security services.

Established in 1993 using an existing blacklist from the Economic League, The Consulting Association (TCA) was a secret body comprised of most major construction companies. Between them, they illegally orchestrated the blacklisting of thousands of construction workers.

Every job applicant on major building projects had their name checked against TCA’s blacklist. If there was a match, the worker would be refused work or dismissed. These checks were done on hundreds of thousands of workers a year.

It wasn’t just the major firms who kept union activists under surveillance and contributed to blacklisting – it was the same political police who are at the heart of the Undercover Policing Inquiry.

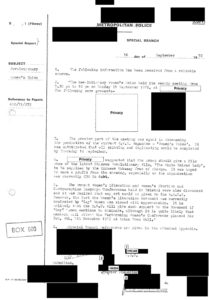

The police’s internal spycops investigation, Operation Herne, produced a report on blacklisting which concluded:

‘Police, including Special Branches and the Security Services, supplied information to the blacklist funded by the country’s major construction firms, The Consulting Association’

SPECIAL BRANCH INDUSTRIAL UNIT

The Special Branch Industrial Unit was established in 1970, ‘with the aim of monitoring trade unionists from teaching to the docks’. Special Branch files were effectively a database for MI5, private firms and others to find out about trade union activists.

Spycops often worked for the Industrial Unit, before or after being deployed undercover. One was HN336 ‘Dick Epps’, who told the Inquiry that Chief Superintendent Herbert Guy ‘Bert’ Lawrenson, head of the Metropolitan Police Special Branch’s union-monitoring C Squad in those early days, went to work for the Economic League.

One can readily imagine Special Branch Industrial Unit officers had a ready exchange of information with Lawrenson, their former boss, the man who quite possibly hired and trained them.

The Operation Herne report confirmed that, prior to The Consulting Association’s foundation in the 1990s:

‘Special Branches throughout the UK had direct contact with the Economic League’

MODERN POLICE HELP FOR BLACKLISTERS

As well as Special Branch files, police intelligence on political activists was later kept on the National Domestic Extremism Database, which holds files on thousands of citizens whom the State considers ‘domestic extremists’, many of whom have committed no crime whatsoever.

One of the units responsible for the database was the National Extremism Tactical Coordination Unit (NETCU), whose Detective Chief Inspector Gordon Mills gave a presentation to a secret Consulting Association meeting in 2008. This was a senior police officer helping TCA, a company whose work was illegal.

NETCU and the Special Branch Industrial Unit, along with all the spycops units, are now absorbed into the Met’s Counter Terrorism Command. State spying on unions is now classified as counter-terrorism.

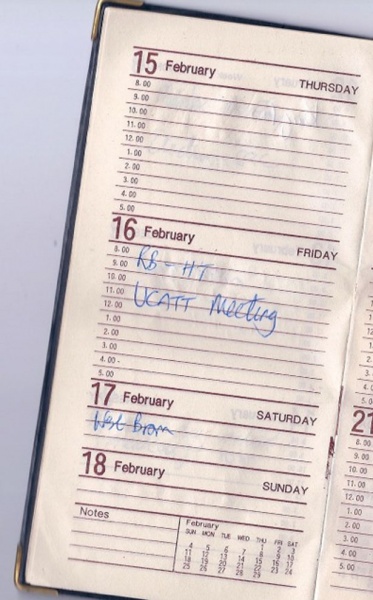

PERSONAL TARGETING

Page from undercover officer Mark Jenner’s 1996 diary, showing his attendance at a UCATT meeting

Smith then focused on a small group of union activists on the blacklist of which he was part. From the early 1990s until mid 2000s, they were spied on by three separate spycops: Peter Francis, Mark Jenner, and Carlo Soracchi.

Mark Jenner joined the construction union UCATT as ‘Mark Cassidy’. He attended picket lines, protests, and conferences, and even chaired meetings. Smith flatly accused Jenner, and through him the British State, of interfering with the internal democratic processes of an independent trade union.

When Jenner’s deployment was coming to an end, another spycop, Carlo Soracchi, using the name ‘Carlo Neri’, was sent to spy on the same group of activists. Soracchi was an agent provocateur, trying in vain to incite union members to commit arson against a charity shop he claimed was run by Roberto Fiore, leader of Italian fascist party Forza Nuova.

Jenner deceived ‘Alison’, an activist for the National Union of Teachers, into a five year co-habiting relationship during his deployment. Soracchi deceived two women into relationships with him during his deployment – Donna McLean, a Transport and General Workers Union rep from a homelessness charity, and ‘Lindsey‘ who was also an active trade unionist.

SDS officer Carlo Soracchi

If the purpose of the spycop units was genuinely, as the police claim, to detect serious criminality or public disorder, why, in over ten years of spying, were none of these people ever charged or prosecuted with a serious criminal offence? This is nothing to do with disorder or crime, it’s purely political policing.

Smith said the police can claim all they like that they were protecting democracy. But by spying on trade union members and colluding with blacklisting, spycops are actually just protecting big business and capitalism. Capitalism and democracy are not the same thing.

OFFICER HN348 ‘SANDRA DAVIES’

Giving over a long session to questioning Special Demonstration Squad officer HN348 ‘Sandra Davies’ seemed something of an odd proposition, as she appeared to have had an uneventful deployment.

As it turned out, this was the point; her testimony demonstrated the pointlessness of many deployments, and the total absence of any consideration of the impact of this intrusion on the lives of those targeted.

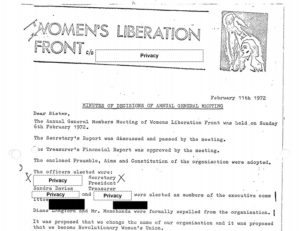

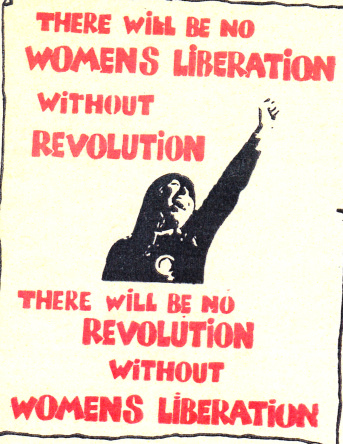

The SDS’ annual report of 1971 confirmed that she was recruited for her gender:

‘The arrival of a second woman officer has added considerably to the squad’s flexibility and has proved invaluable in the comparatively recent field of women’s liberation.’

Davies infiltrated the Women’s Liberation Front (WLF). A small feminist group with Maoist leanings, its meetings were attended by about 12 people, hosted at one of the member’s homes.

As a constable, she had the same powers and responsibilities as her male colleagues but, as a female officer, was only paid 90% of the men’s salary.

In the SDS, she was sent to spy on the WLF who, according to her, mainly campaigned for equal pay, free contraception and free nurseries.

SUBVERSIVE BAKING

Davies reported on the WLF supplying home-made sweets and cakes for a children’s Christmas party organised by the Black Unity and Freedom Party. She also reported on the WLF holding a jumble sale. Both of these reports were copied to MI5.

She was elected treasurer of the WLF. As part of the six-strong executive committee, she took part in the expulsion of several members that led to the group’s decline.

Looking back, she continued:

‘I do not think my work really yielded any good intelligence, but I eliminated the Women’s Liberation Front from public order concerns’

That is a mitigation that could be applied to thought-crime spying on literally anyone. More to the point, it was a fact that must have been obvious very early on in her deployment. And yet she spent two years, full-time, spying on that group.

There was no suggestion that her managers gave much thought to whether what she was doing was worthwhile. As with other deployments, it seems that once they had their spycops in place, keeping them there was more important than the substance of the information they gathered.

The rights of the people being spied on – who had police officers in their lives and homes week after week – didn’t get a look-in.

MENTAL GYMNASTICS

Davies has been granted anonymity by the Inquiry. In her ‘impact statement’, she said that she wanted anonymity because she would be embarrassed if the group’s main activist found out the truth. She also said her reputation would be tainted if her friends found out she had been a spycop.

This is an extraordinary mental gymnastics – when we question the purpose of spycops, the police tell us that they’re doing vital & noble work ensuring the safety of everyone, yet when we ask why they want anonymity, they say it would be humiliating to be known as one.

SUMMARY WITHOUT QUESTION

Rather than insisting that all of the surviving former spycops give evidence, the Inquiry has chosen not to ‘call’ the majority of them.

Instead, the Inquiry team have prepared a short summary of each officer’s witness statement, and read it out. There is no opportunity for anyone to question the spycops, giving rise to a worry that their real history will remain hidden.

Less anticipated was that the Inquiry would be more inclined to cover up an officer’s wrongdoing than the officer themselves.

OFFICER HN339 ‘STEWART GOODMAN’

Officer HN339, ‘Stewart Goodman’, was deployed undercover from 1970 to 1971, initially against the anti-apartheid groups. He joined the Lambeth branch of the International Socialists (now the Socialist Workers Party), where – mirroring Doug Edwards’ and Sandra Davies’ roles – he became treasurer.

Speaking for the Inquiry, Elizabeth Campbell summarised:

‘HN339 recalls being involved in some fly-posting while in his cover identity, but no other criminal activity. Near the end of his deployment, HN339 was involved in a road traffic accident while driving an unmarked police car, which necessitated the involvement of his supervisors on the SDS.

‘HN339 states that he does not remember much about his withdrawal from the field, but suspects that this event may have been a catalyst for the end of his deployment.’

Goodman was not merely ‘involved in a road traffic accident’.

For those willing to wade through the documents, on page 18 of Goodman’s witness statement he said:

‘I crashed my unmarked police car. I had been at a pub with activists and I would have parked the car away from the pub so as not to arouse suspicion. I drove home while under the influence of alcohol and crashed the car into a tree’.

The car was a write-off. When uniformed officers arrived, Goodman breached SDS protocol and broke cover, telling them he was an undercover colleague. Rather than arresting and charging him, they drove him home.

He was eventually charged and went to court, accompanied by his manager Phil Saunders. He believes he was prosecuted under his false identity and that Saunders briefed the magistrates. He was convicted and fined.

INQUIRY COVERING UP THE TRUTH

It is utterly outrageous that the Inquiry told the public that the only crime Goodman committed undercover was fly-posting and then, literally in the next sentence, referred to a much more serious criminal offence.

Investigating the often-corrupt relationships between the spycops and the courts is one of the stated purposes of this Inquiry, yet here they are deliberately burying examples of wrong-doing which the officers themselves admit.

Because Goodman wasn’t called to give evidence to the Inquiry in person, there was no way to question him about the possibility of judicial corruption.

Beyond that, we are left wondering what else has been covered up in this way, and lies there among the hundreds of pages the Inquiry bulk-publishes after it has finished discussing a given officer’s deployment.

OFFICER HN343 ‘JOHN CLINTON’

Another summary was given for HN343 ‘John Clinton’, who served in the SDS from early 1971 until late 1974, infiltrating groups including the International Socialists (IS).

Clinton considered the IS to be subversive, though he had an exceptionally broad definition of the word, writing in his witness statement:

‘I witnessed a lot of subversive activity whilst I was deployed undercover… During industrial disputes they would deploy to picket lines and stand there in solidarity.’

He reported on campaigns and issues supported by the group, such as women’s liberation, tenants’ rights and the Anti-Apartheid Movement.

WHAT HE DIDN’T SAY

Clinton was infiltrating International Socialists in London in the summer of 1974, yet he made no mention of their involvement in the large anti-fascist demonstration on 15 June 1974 at which a protester, Kevin Gately, was killed by police.

It was the first time anyone had died on a demonstration in Britain for over 50 years. It was a huge cause célèbre for the left. Clinton didn’t mention this, nor any of the vigils for Gately and campaigning that followed among IS and the broader left.

It is a glaring omission that arouses suspicion. Given the SDS’s avid focus on such justice campaigns later on, it would be very odd indeed if their officer in IS didn’t participate, let alone fail to recall it as significant.

As with Stewart Goodman earlier, because this was an Inquiry lawyer reading out a hasty summary, nobody was able to question Clinton about any of this.

OFFICER HN345 ‘PETER FREDERICKS’

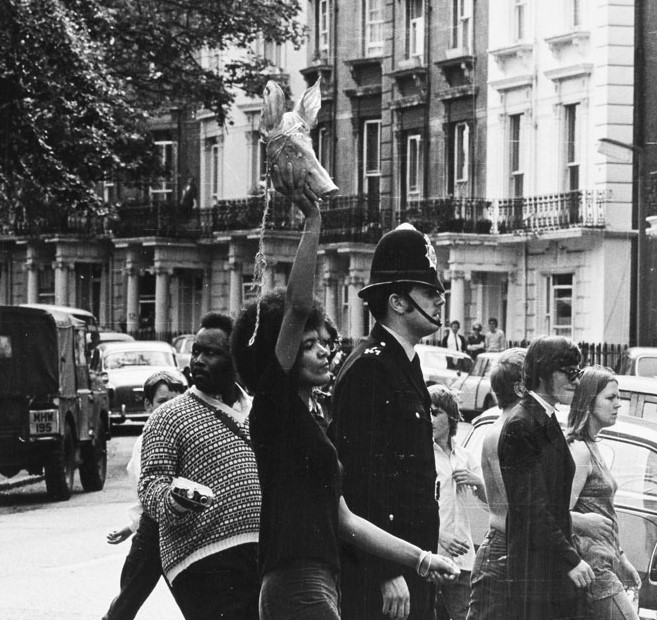

Barbara Beese on the protest for which she would be arrested as one of the Mangrove 9, Aug 9 1970

Spycop HN345, ‘Peter Fredericks‘, describes himself as being ‘of mixed heritage’. He was deployed by the SDS for about six months in 1971.

Fredericks was asked if he thought he was asked to target the Black Power movement because of his race.

‘No. I never came across anything vaguely associated with that statement,’ he replied, as if the police might have sent a white officer to infiltrate Black Power groups instead.

ANOTHER FAULTY MEMORY

Fredericks was asked if he remembered the case of the Mangrove 9:

‘Not clearly, no’.

The disbelieving scepticism of the barrister asking was clear even on the plain type of the transcript:

‘It doesn’t ring any bells at all? Let me see if I can help you.’

The Inquiry was then told how, on 9 August 1970 – a few months before Fredericks joined the SDS – there was a demonstration in Notting Hill about the police harassment of the Mangrove restaurant. As a result of that demonstration, nine black activists were arrested and prosecuted for riot.

There was a defence campaign set up, and their trial started at the Old Bailey in October 1971, while Fredericks was undercover in Black Power groups.

Fredericks said:

‘I was not involved closely with them. I would have read about it in the papers. I would have known something, perhaps.’

As with John Clinton’s failure to mention the death of Kevin Gately, this absence of memory is simply not credible. Even the barrister knew it:

‘And you don’t remember any conversations with any of your SOS colleagues, or anybody else in Special Branch, about this seminal event in the history of the Black Power Movement?’

Fredericks determinedly kept the lid on the can of worms:

‘Definitely not. Definitely not.’

In fact, the totality of Fredericks’s recollections of Black Power seemed to amount to very little at all.

‘SAMPLE THE PRODUCT’

When asked about intimate relationships between undercover officers and the people they spied on, his jaw-dropping response led to collective gasps of horror:

‘I have, if you like, a phrase in my head which helps guide me here. If you ask me to infiltrate some drug dealers, you can’t point the finger at me if I sample the product.

‘If these people are in a certain environment where it is necessary to engage a little more deeply, then shall we say, I find this acceptable, but I do worry about the consequences for the female and any children that may result from the relationship. That would be dangerous. So yes, it shouldn’t be done.’

Tom Fowler was live-tweeting from the Inquiry venue, watching on a screen. He reported:

‘Reading the words from the transcript is bad enough, but when you see it delivered with a wide grin, tongue darting in & out of the mouth, with the final “it shouldn’t be done” tacked on to the end with a complete lack of sincerity, it reveals an extreme misogyny as well as a certain sadism; a psychopathic willingness to use people for political ends, whilst enjoying it at the same time’

It serves to underline the problem of the Inquiry only providing a live transcript and thereby missing all the tone and inflection, something highlighted on the COPS blog earlier in the week.

WHAT NEXT?

The Undercover Policing Inquiry will now take a break to prepare for the next set of hearings. These will examine the Special Demonstration Squad 1973-82, and are expected to be held in March or April 2021.

Whenever they happen, COPS will be live-tweeting the hearings and producing daily reports, as well as weekly summaries like this one.

All our daily and weekly reports are linked from our Inquiry page.

There was a talk by Leila Hassan from the Black Unity and Freedom Party (BUFP)

There was a talk by Leila Hassan from the Black Unity and Freedom Party (BUFP)