UCPI Daily Report, 23 Oct 2025: ‘Ellie’ evidence

Tranche 3 Phase 1, Day 6

23 October 2025

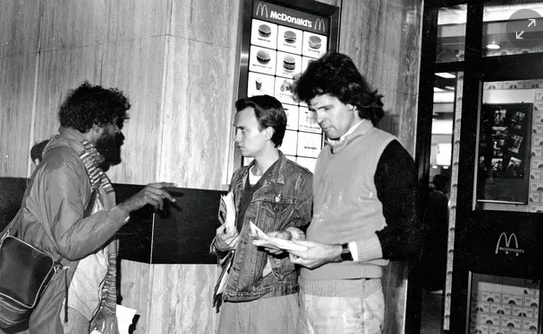

Spycop James Thomson photographed by ‘Ellie’ in Singapore, September 2001. He travelled there against the orders of his managers.

INTRODUCTION

‘Ellie’ (not her real name) was deceived into a one-year intimate, sexual relationship by undercover officer HN16 James Thomson, who she knew as ‘James Straven’. He was deployed 1997 to 2002. However, he remained in contact with Ellie for a further 16 years after his deployment ended, long after she had left London, and he continued to conceal his true identity from her.

She gave evidence to the Undercover Policing Inquiry remotely from Australia on Thursday 23 October and Monday 3 November 2025.

This hearing was part of the Undercover Policing Inquiry’s ‘Tranche 3 Phase 1’ which will run from October 2025 to July 2026 (with two breaks), examining the final 15 years of the Metropolitan Police’s Special Demonstration Squad, 1993-2008.

The Undercover Policing Inquiry (UCPI) is an independent, judge-led inquiry into undercover policing in England and Wales. Its main focus is the activity of two units who deployed long-term undercover officers into a variety of political groups: the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS, 1968-2008) and the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU, 1999-2011). Spycops from these units lived as activists for years at a time, spying on more than 1,000 groups.

There are transcripts and videos of this hearing available on the Inquiry website’s pages for 23 October and 3 November.

Ellie has made a 38-page written statement [UCPI0000038206]. She was questioned by Sarah Hemingway, Second Junior Counsel to the Inquiry.

BACKGROUND

Ellie was not an animal rights activist. Thomson described her as an ‘animal welfare sympathiser but not an extremist or an activist’ and she agrees with this. She had an interest in animal welfare, and began volunteering at a local wildlife hospital when she was 18 years old.

She became friends with ‘Wendy’ (who gave evidence on the afternoon of 23 October) at the wildlife hospital. Wendy was a vegan and an activist. It was through her that Ellie met Thomson, when she was 20 years old, when Thomson went to help out at the wildlife hospital in 1999 or 2000.

Q. What was the extent of your interaction with James on that occasion?

A. Minimal. The wildlife hospital was quite busy. I had a lot of work on. I cannot imagine I would have said more than a few words.

Yet Thomson asked Wendy for Ellie’s number, and told her he wanted to date her.

Around that time, Wendy’s mother was dying. She was always back and forth to the hospital and Thomson was very supportive, driving her there and taking her to other places. Ellie assumed Thomson was interested in Wendy, but she didn’t see him that way, they were just very close friends.

Meanwhile, Ellie was having a bad time at the wildlife hospital because her boss was sexually harassing her. He put a lot of pressure on her, asking her out, firing her when she refused to go out with him, withholding staff pay and threatening to kill himself:

‘He gradually he got more and more control over everything and we ended up sort of living under his roof, eating his food, asking to be paid, and then there was just drama after drama. And just harassing and harassing and harassing and it just wears you down after a while…

He would sort of climb into my bed at night. And then if I got out there would be a big argument, which would go on for hours and I would end up sort of wedged in the corner and I put pillows behind me to kind of keep him away…

We’d asked him a few times for a contract. That didn’t go down well, so we never got the contract…

It just gradually got worse and worse and worse until he fired me again and when he went, “Okay, you can come back”, and I said, “No, I am done”.’

The harassment had gone on for 6-8 months. When she finally walked away Ellie lost her job and her home. Wendy helped Ellie out and let her move into Wendy’s mother’s house after she died.

At the time she started dating Thomson, Ellie explains she was:

‘An awkward, geeky, naive, possibly a bit sheltered, 21-year old. I’d moved out of home and moved into the wildlife hospital and that was my first step into the real world, and I had screwed that up quite spectacularly…

I just walked straight into a bad situation and then ended up homeless within a period of a year of moving out…

I would cry at the drop of a hat. A simple task that should have taken five minutes seemed to take half an hour. I was sleeping all the time, I didn’t have a lot of motivation. I was quite underweight.’

That was the situation Ellie was in when Thomson started dating her. It fits a pattern we have seen time and time again in this Inquiry of undercover police officers identifying vulnerable women much younger than themselves to target and groom into intimate, sexual relationships. Thomson’s manager HN10 Bob Lambert with ‘Jacqui’, HN2 Andy Coles with ‘Jessica’, and HN5 John Dines with Helen Steel. By any definition, the Special Demonstration Squad was a grooming gang.

ROMANTIC RELATIONSHIP

Thomson told Ellie he was 33 years old. He seemed to be very conscious of the age gap. Ellie explained that when they first started dating, the 13-year difference concerned her somewhat too. It was actually even wider.

‘There was an incident when we were having dinner and he mentioned his children and I worked out that he would have been quite young when he’d had his first child. And that had made him a bit uncomfortable…

I got some random phone call from him saying that he had spoken to “Sara” and she had pointed out that he had his age wrong and he was actually 36 and not 33…

I thought he obviously always knew his age, he just had lied to me about his age because he was conscious of the age difference, but he was actually 36 years old.’

Sara gave evidence on 17 October where she made clear that the conversation never took place. She was certain that she would not have said what he claimed because she always believed he was two years younger than her, which would have made him 33 years old.

Hemingway asked Ellie about the age gap:

Q. Did his being older cause you any real concern at the time?

A. When I thought he was 33, that was sort of the upper limit. I know my sister had a concern about that. But I was okay with him being 33. When I found out he was 36, that was an issue, but at that point we were dating and I liked him and it wasn’t an issue enough to end it.

In fact, Thomson was 37 years old when he started dating Ellie, who was just 21.

They would meet up once a week, going out for meals, cinema dates and suchlike. That progressed to day trips on the back of Thomson’s motorbike, staying at B&Bs.

Hemingway then read out the now infamous section of the 1995 SDS Tradecraft Manual [MPS-0527597] that recommends undercover officers have:

‘fleeting disastrous relationships with individuals who are not important to your sources of information’.

Ellie agrees that her relationship with him did not fit this description. She was very close to Wendy, who was part of his target group, and she gave him unfettered access to her home.

FAKE IDENTITY

Thomson told Ellie that his background was Scottish, and his father was a Laird. He claimed to be the black sheep of a military family, and he said his sister was an actress. She notes that this seems to fit with him using the identity of James Christopher Swinton, brother of the actress Tilda Swinton. She asks the Inquiry to investigate this.

Thomson told her he had three children with a previous partner. He said the relationship had been unhappy, but every time they were going to split she became pregnant.

Ellie remembers finding Thomson’s home strange:

‘His cover accommodation was a shock when I first got there. It just – he was always quite well presented and well turned you out, his clothes were always quite neat. I know some of the hunt sabs, including “Wendy”, used to laugh at him for ironing his jeans.

So when I saw his accommodation, it wasn’t what I expected. It was very run down. I think there were two very thready towels in the bathroom. There was nothing personal in there at all. There was hardly any food in the fridge. It didn’t look lived in and it didn’t fit with him.’

He told her he worked as a locations manager, and that he had worked with the BBC before he set up his own company. He was away a lot with work, and she remembers his ‘James Straven’ name appearing on the credits of a TV show he’d worked on.

Ellie described her relationship with Thomson:

‘From my point of view, he was my first what I would call “proper” relationship. So anybody that I dated before hadn’t been – the feelings hadn’t been that intense, it hadn’t been there. This one I was very comfortable in quite quickly. I could see it going on for a long time…

It was easy, it was nice, there was no pressure, I could be myself. Apparently not, but he was my first love, basically. My first proper intense relationship…

I was having a conversation once, I do remember that, with “Wendy” and we were talking about people cheating on each other and I said, “Yes, I don’t think James would do that” and she went, “No, he’s not really the type. He doesn’t seem to be the type”. We got that incredibly wrong, but I was under the impression it was monogamous…

the fact that it was a nice low pace and we weren’t in each other’s pockets suited me very well. And then when we were together it was lovely. It was romantic, it was caring, it was sweet, it was easy, it was fun. It was great, and then I still had time for myself.’

She says Thomson was reluctant to have sex without contraception, but he didn’t use condoms.

‘So I went to maybe look at going on the pill. And talking with my doctor, we trialled the injection… once that was done we never used any other forms of contraception.’

On 17 October we heard painful evidence from Sara, Thomson’s partner prior to Ellie, about how Thomson told her in great detail that he had traumatic childhood experiences of sexual abuse.

Hemingway asked Ellie if he ever brought that up with her:

‘The rape? No, that was fairly horrific that he would say that. He did say that he had had a sexual relationship with a school nurse, but he seemed quite proud of that. That was only really mentioned once.’

Thomson never seemed to have any issues with having a sexual relationship with Ellie.

Ellie explained he was always very generous and paid for trips away and meals out.

‘I didn’t have a lot of money, especially because after the wildlife hospital I was finding my feet and trying to get sort of – by the time you’ve paid bills there’s not a lot left…

I did try and pay halves as much as I could, but… he paid for a lot of those things.’

He also paid for Ellie to do her motorbike training course, and they travelled together to Indonesia and Singapore in September/ October 2001.

INDONESIA AND SINGAPORE

The trip was Thomson’s suggestion. He asked her if she wanted to come and she jumped at the chance. She is sure that he paid for her to go and organised everything.

He told her he was going there to visit a friend, known at the Inquiry as ‘L4’, who had nearly died from being run over by a hunter in a Land Rover. Ellie had met L4 a couple of times.

‘What I found out later – which I didn’t know at the time – was that his partner had contacted James and she had said that she was exceptionally worried about L4, because of things that had happened, and she was worried that he was over there isolated and alone, and she paid for James to go over and be with him, because she knew they were friends and she just wanted him to be supportive and be a supportive friend over there.’

The trial of the hunter accused of nearly killing L4 had collapsed by that time.

Ellie is certain that Thomson paid for everything:

‘He organised everything, I literally just floated along…

He did all the tickets and the passports and everything, and he did all the checking in and all the sorting out and I just thought this is just something he does.’

Ellie never saw Thomson’s passport.

Hemingway then read a long extract from a police report into Thomson’s undercover activities written in 2002 at the end of his deployment [MPS-0719722]:

‘Indonesia. Matters began to come to a head in early September 2021 when Detective Sergeant Thomson sought authorisation to visit L4 in Indonesia. His operational grounds for doing so were based on a need to brief L4 on legal issues around the L5 trial.

His request was initially authorised, but events soon overtook that decision with the attack on 11 September.

It quickly became apparent, both from media sources as well as the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, that there were too many risks attached to such a visit, particularly in view of the anti-American and British fervour being fomented in Indonesia. Detective Sergeant Thomson was therefore instructed not to travel to the Far East.

He was patently dismissive of the decision and its rationale, but advised the office that he would travel to France on annual leave instead (from 26 September to 5 October)…

By early November, enquiries had established that Detective Sergeant Thomson had indeed travelled to Singapore and Indonesia during his leave period using his covert identity.

As a result of this serious breach of operational security and discipline, he was interviewed by Detective Chief Superintendent Colin Black and informed that his operation would be concluded at the earliest opportunity – a final date being set of 27 January 2002.

Detective Sergeant Thomson continued to maintain that he held the moral high ground and justified his decision to override the veto on travel to Indonesia on the basis of operational necessity. There was, incidentally, no intelligence feedback from this trip.’

Ellie’s account is that she and Thomson didn’t actually spend much time with L4, only a few days before they went to Singapore, where he took her to the iconic luxury hotel Raffles to have a Singapore Sling cocktail:

‘He was quite keen on doing that. That seemed to be a bucket list thing…

I have found out since then that this was a bit of a place that all of the undercovers were quite keen on visiting. There’s a Raffles in London, where Ian Fleming wrote the James Bond stories, and that seems to be a thing for them, that they all like. I didn’t know that at the time.’

Spycop James Thomson with Ellie at the Raffles Hotel, Singapore, 2001. He’d travelled there against the instructions of his managers.

Ellie knew that Thomson had the nickname ‘James Blond’, and she knows he was aware of the name, because she called him that herself sometimes.

She believes it had come about because of suspicions about him when he first appeared at the hunt sabs. She says that his whole persona fitted the rogue character breaking the rules.

Ellie says that in retrospect, it fits with her experience of him that he was having sex on the job.

Thomson told Ellie to give him the roll of film from her camera when they got back from Indonesia and Singapore so that he could get it developed with his.

He gave her a collage of photos, plane tickets, a coaster from Raffles and other memorabilia, but there were no pictures of him in it. He told her all the photos taken by her ‘didn’t come out’.

She only has two of her photos from that trip which were the ones that remained in her camera. Everything else was gone.

THOMSON’S WITHDRAWAL

At the start of 2002, Thomson told Ellie that his ex-partner was emigrating to San Francisco and taking the children. He said he was going to move over there to be close to them.

‘From there things did progress quite quickly. I was round at his place, he went out, he said he had to go out for a meeting. When he came back he was a bit quiet and a bit, you know, in a little bit of a bad mood and he said things were progressing faster than he wanted, and he was probably going to be leaving quicker than he anticipated.’

He eventually left around March 2002. The SDS’s ‘extraction plan’ for Thomson’s deployment, codenamed ‘Magenta Triangle’ [MPS-0007389] shows that he had been instructed by Detective Chief Superintendent Colin Black to terminate his operation by 27 January 2002. That timeline was extended at Thomson’s request (as recorded in the later overview document MPS-0719722).

We were shown Thomson’s phone records [MPS-0719641]. They show 301 calls or texts to Ellie between April 2001 to April 2002, almost one a day, with the comment ‘no reporting’. In comparison, the records show 226 calls or texts to Thomson’s ex-wife and children and 627 to his real-life partner during the same period.

Before Thomson left, supposedly to live in America, he paid for Ellie to have a follow-up motorbike course. He sent her a card enclosing a voucher for the course in which he quoted poetry [UCPI0000038280]. It ends:

‘See you in the South of France! With love, James’.

She felt hollow at him moving away.

‘I wasn’t quite sure what he was going to do. Everything seemed a bit up in the air. He seemed to have a lot on his plate, so I did leave the ball in his court. So when he left I wasn’t sure if I would hear from him again.’

She says if he had just gone, and never contacted her again, she would have got on with her life. But that’s not what he did.

ONGOING CONTACT

After leaving and claiming he had gone to live in the USA, Thomson continued to contact Ellie. His deployment officially ended on 25 March 2002. His first email to Ellie after he left is dated 8 May 2002 [UCPI0000038289].

‘I could rarely get a genuine insight into how you felt about things when I was with you I’d definitely want to know now.

As there is no longer any possibility of my being able to look at you whilst you’re ‘talking’ I am hoping it’ll be easier for you. I do want to know that you’re happy after all. I also want to know that you’re grabbing the life that should be yours.

You are a hell of a lot smarter than either you let on, or allow yourself to believe. But when you get careless and distracted it leaks out, mostly through your sense of humour and wit (which I miss hugely, by the way) as you often don’t have the confidence to force an issue even when you know you’re right…

I don’t see you ever ducking an adventure, so it’s just a matter of being in the right places to let them happen to you. I really do want you to have as much fun in your life as I’ve had (and hopefully will continue to have) in mine. It’ll be fun meeting up when you’re old and grey, and I am a ghost, to swap war stories – all to be horribly exaggerated in the interests of a good yarn of course…

I also need you to do a spot of considering. I am likely to be heading for Europe in a while (the Cannes Film Festival, Daaaaarling) and will have to stop off in London either on the way there or on the way back.

So what I need know is how you feel about meeting up for a curry or pizza or some such. Is it too soon and how do you feel, et cetera, et cetera.

Have a serious think and let me know. I won’t take offence either way and will continue to bother you via email until much later when we can meet in the Pyrenees or Alps on motorcycles.

Oh, and can you not mention this to anyone else as I don’t want to be obliged to chase around seeing everyone – it’ll only be a short visit re that script thing.

Anyway, that’ll do for now. It’s far too hot to remain out here without a swim.

Take care my love. Yours aye. James X.’

This was the start of many years of email communication. He did the same with Wendy. Ellie is still baffled by his reasoning.

‘I don’t know why he kept in touch with us. I don’t know what he was playing at, at all.’

Thomson’s emails are deeply personal, flirtatious and flattering. Wendy knew Ellie was still in touch with Thomson. Other friends of hers knew they were still in contact as well. Ellie and Thomson would meet up every year or two:

‘It picked up where it left off, it was like going on a date again, yes, it just slipped straight back into that…

Always a goodbye kiss. Like an intimate kiss. I think sometimes holding hands. And then later on, sort of over the years, there were very intimate moments…

It was more than friendship, but it wasn’t a relationship. It was somewhere in the middle… I never really labelled it.’

DECEIT ACROSS THE WORLD

Ellie moved abroad in 2005, but the connection with Thomson continued.

‘Whenever I was going – and the same with “Wendy” – whenever we were going back to the UK to visit, we would email and say these are the dates we are going to be back, if you can make it back there and we can catch up, that would be great. And he would very often manage that… In fact he was one of the most consistent relationships I had.’

From Thomson’s emails to Ellie [UCPI0000038281], he seemed to be travelling the world. There were emails claiming to be from Tunisia, Malaysia, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Libya, Malta and Kuala Lumpur (from where he asked Ellie to visit him).

We were shown one email where he said he was in Iraq:

‘I am up in the north this time in Kurdistan – so quite near the Iranian, Syrian and Turkish borders, which is good as I’ve not been here before.

Tomorrow the rough boys are taking me up to their ranges in the mountains to play with their big guns – although now I write that it sounds a bit dodgy! But it’s not as if any of them are hairdressers, what do you think? So I’ll try to get a photo of me being all manly, as I gather that’s how one impresses you antipodeans.’

This email was sent in 2008, six years after Thomson’s deployment ended. He told Ellie that he was making all those trips to dangerous war zones as part of a location manager job for American TV news. In fact, he was in the Metropolitan Police’s Specialist Operations Unit until 2012.

When the spycops scandal broke after EN12 Mark Kennedy was unmasked in 2010, Thomson was removed from operational duties to protect the Met and preserve his anonymity while they assessed the risk that might arise from the public disclosure in the media.

From then until his retirement in June 2014, he says he only fulfilled administrative duties in and around New Scotland Yard [UCPI0000035553].

The emails to Ellie were emotional. They were very special to her. She looked forward to receiving the next one. He asked her to send him a Google Earth link to where she was living after she moved house.

The emails often contained attempts to plan to meet up physically, something they managed to do on numerous occasions. We were shown one email which Thomson sent shortly after they met up for the day in England and gone out on motorbikes:

‘Whilst I hadn’t forgotten that I missed you, I hadn’t fully remembered why – a conscious effort on my part admittedly – and even seeing you so briefly brought it all back.

I had a truly wonderful time. I always did in your company. As for the attraction I so obviously still feel for you; suffice to say I’ve never felt as frustrated as I did knowing you were in a hotel near Heathrow without a chaperone while I was stuck in Scotland!

And all for the want of a little planning (or so I told myself). Actually I had made promises to myself to behave so I didn’t disconcert you, but I was perfectly happy to bin that idea even while on a motorbike.’

SEXUAL SUGGESTIONS

Thomson frequently asked Ellie to send him photographs, and he gives them explicitly sexual connotations:

‘I am expecting many paragraphs and photos – anything involving lingerie and you will no doubt help with the aforementioned aargh condition you left me in by being at Heathrow when I was in Scotland (note how it’s all your fault in my head at least).’

Thomson frequently referred to his own sexual frustration in emails with ‘aaargh’ as the subject line, and repeatedly asked Ellie to send photos of herself in lingerie.

On 23 October 2011, which is more than a year after spycop EN12 Mark Kennedy was uncovered and after eight women had filed claims against the police for deceitful relationships, Thomson emailed Ellie saying he was in Libya.

He told her he hadn’t moved on and was suffering from sexual frustration from not being able to have sex with her. Many of his emails were sexually suggestive and Ellie says it remained very common for Thomson to ask to meet up or request her to send him explicit photos. His manner is incredibly salacious, signing off emails with comments like:

‘sent with all my love as ever was, and still thinking of you far more than is good for me (and not always undressed)’

Ellie explained that she did not send him the photos he asked for and this sort of talk was pretty one sided. She didn’t deter him, but she just isn’t that sort of person.

We were shown a document dated 19 October 2001 [MPS-0719701], planning Thomson’s extraction from deployment. It specifically states that he should gradually be sending shorter and more rushed emails, displaying less interest in the members of his target group with more focus on himself and his own career in order to diminish his standing as a friend.

Yet ten years later he was doing nothing of the sort. On the contrary, he was still expressing a great deal of interest and desire to meet up and spend time with Ellie.

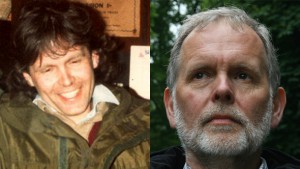

James Thomson (centre, Barbour jacket, looking at camera) working as a protection officer for Tony Blair, Dublin, September 2010

In his own witness statement, Thomson admits he stayed in contact with Ellie, claiming they met up once every three or four years. Ellie says there was more contact than that, they met up more like once a year. Ellie was aware that Thomson would also meet up with Wendy when she went back to the UK.

In an email dated 15 April 2012, Thomson refers to going to Afghanistan which he says he prefers to the office job. He sent her photos of himself with lots of people in uniform with guns.

By that time, he had been removed from working in close protection of prominent public figures, because the media had picked up on the existence of the SDS and he might be recognised.

Thomson retired from the Met in 2014 but his contact with Ellie continued. In fact, he stayed in contact for 16 years after his deployment ended, from 2002 until 2018.

It appears from emails in 2014 that Thomson was trying to work out exactly where Ellie was living. In June 2014 he asked her about the location of her current home. He tried to arrange meeting up with her, and makes very suggestive comments, but he also apologises for those, saying ‘it’s your body after all’. His emails also express contempt for what he calls ‘the powers that be’ – his management, the rules and regulations.

In retrospect Ellie sees all that in context of the fact that undercover officers were being uncovered, and it appears that he has contacts who could be quite threatening. She still feels vulnerable to him taking revenge on her, especially because he knows where she lives.

THE PUBLIC INQUIRY

Ellie has exhibited text messages between her and Thomson that show he chased her to meet up in June 2015 and visit her at her hotel, where they had sex. This was more than a year after the Undercover Policing Inquiry had been announced.

On 17 April 2018, Thomson told the Inquiry that he only had an old email address for Ellie. He did not admit he was still in contact with her by calls and texts.

At the same time, Thomson messaged Ellie on WhatsApp asking if they could talk, and the following day, 18 April 2018, they spoke on the phone.

Ellie recounts:

‘So he rang and I had gone into my room for some privacy, and there was a few seconds of just superficial, “Hi, how are you going, how are you doing”.

And then he’s just launched into saying that back when we were dating, he had actually been undercover – and it was about a half an hour conversation where he said, “Look, there’s a bit of an inquiry going on, they may try and contact you”. And then talked about it a little bit…

The conversation itself was a bit of a shock, and there is just this weird numbness that happened. Just like – just I have never felt anything like it. I can’t explain it. Just really – just a strange feeling, I didn’t quite know what to think, I didn’t quite know what to ask, I wasn’t quite making sense of it. I thought, the way he was talking, that maybe everything was real apart from his job. I thought maybe he wasn’t a locations manager.

And it was only as things progressed that he was sort of talking about Wendy and all the rest of it, and then he said, “the Inquiry will probably tell you my real name”, and that hit quite hard. Because I was like, “oh no, everything’s a lie”, and that hit home that little bit…

We were housemates again, Wendy and I, and she was in the lounge. And he’d said “maybe don’t tell Wendy, she’ll be angry”… I did not know what to do. So I went and had a shower.

I sat in the shower, had my sort of forehead against the tiles and I just thought for a bit and just thought “just don’t do anything for 24 hours and then tell Wendy and don’t plan anything beyond that”.’

Wendy had already heard about the Inquiry, so she pretty quickly cottoned on to what was going on. They both contacted the Inquiry. Thomson texted her again after that, saying he knew she had spoken to the Inquiry:

‘Hi Ellie.

Hope this finds you doing well. Heard from solicitors to say you had been in touch with the Inquiry in the UK. As I said when we spoke that’s absolutely your right and I will continue to respect whatever decisions you make.

So, really only wanted to say that if you do still want to discuss any of this at the personal level then that offer also stays open, and I will … be happy to speak to you and to explain, at least as far as I can, anything you want to ask.

Obviously, if you don’t want to speak, or have been advised against it, then please just ignore this.

Good luck for the future, whenever it might take you.’

She felt sick.

‘I was at work and clearly I do not have a poker face. I got the message and I stopped and one of my colleagues went, “oh my god, are you okay?” And I was like, fine”, and I thought I was going to vomit, I had to leave the room.’

THE IMPACT

The discovery of who he really was turned everything on its head. Ellie became very paranoid that she was being watched. She researched the spycops story, trying to work out what was going on, what was happening, who he was, who they were.

Her faith in men and relationships was absolutely shattered:

‘James had sort of restored my faith a little bit in men, being honest and upfront and decent and trustworthy and all of that kind of thing.’

In his witness statement, Thomson says he never considered the impact he would have on Ellie as he never considered she would ever find out. Ellie wonders how long would it have gone on for if the inquiry hadn’t happened.

She was asked to explain how it has impacted her life. She talked about her lack of trust, how she can’t make new friends, and she can’t drive her car without checking the boot and back seat. She became so emotional talking about this that she had to stop.

She asked if she could finish her answers about the impact at the next evidence session. It was clear this is a topic that deeply upsets her, and the Inquiry’s chair, Sir John Mitting, agreed:

‘You are speaking of events that none of us here, I suspect, have ever experienced personally anything even remotely like it. I entirely understand that it is not easy. I say now I am very grateful to you for taking the trouble to give oral evidence to me and you need to apologise for nothing.’

After taking a short break Ellie took a few more questions. She explained that the deceitful relationship Thomson had with her, which spanned 17 years of her life from the age of 21 to 38, disrupted any chance of her finding a suitable partner.

Because it was such a good relationship, she always felt ‘this is what you could have, so don’t settle for anything else’, and in all that time she hasn’t. She didn’t realise that ‘anything else’ would have meant something legitimate and real.

Hemingway then asked her how she feels about Thomson now:

Q. That sense of a James Bond character that we spoke about earlier, this lovable, affable rogue who is, you know, a charming person, doesn’t really do too much damage at the end of the day, what do you say about that? Is he really a James Bond character?

A. I am not going to swear, but no, I don’t think there is anything lovable or roguish about it…

I don’t for one second believe that any of it was legitimate… “Sara”, “Wendy” and myself are very different people, and all three of us thought highly of him…“Sara” and I dated him and we are very different people. So for both of us to think that it was great suggests that he was a bit of a chameleon, which means none of it was genuine… whether he was doing it for his ego or because it was a bit of fun or because he just got off on it, I don’t know. But I know it wasn’t real.

She explained that she read the Undercover Research Group’s article ‘Was my friend a spycop?’, and she realised that Thomson met 12 of the 15 criteria. She sees that his relationship with her gave him legitimacy, and gave him access to Wendy’s home:

‘I woke up at night, he was staying over and he wasn’t in bed. And I was like “oh, maybe he’s gone to the loo or something”, and he didn’t come back for ages. And then I heard him come upstairs.

And the house was on three levels, so you had the kitchen downstairs and then you had the lounge room, a bathroom and my room on the middle level…So he had been down in the kitchen that whole time and the kitchen was sort of at the heart of the home… And it’s where we kept things, certain things, certain paperwork, keys, all of that kind of stuff was all down in that kitchen.

So he had access to that all night, if he wanted it… I think also he had ample opportunity – and this is where I sound paranoid – to plant bugs in the house… so that he could hear us talking and he could hear Wendy talking if she had other friends come round, he could eavesdrop on their conversations.’

COMPLETELY UNNECESSARY

Ellie finished the day on 23 October with an emotional speech:

‘It was just so completely unnecessary. The people that he was going after, the people that they were spying on, that to me, they didn’t need to be spied on. And it was political stuff, it wasn’t even policing.

They weren’t breaking the law, it just seemed to be very politically motivated and very over the top, especially for the kind of information that they were getting, that they were looking for. You could get that by being very superficial, but he did this massive deep dive into everything, I think just for fun and just because he could.

The police – especially the Met – never had the best reputation, and they have been known to be… corrupt, racist, misogynistic, the whole lot. The general consensus is it’s not a case of one bad apple, it’s the whole orchard.

But for them to know that they did this, and to know that they did it to groups that were just speaking out about stuff they believed in, and even think the unions, justice campaigns for families… the level of intrusion was unbelievable… whoever thought that was necessary or relevant just needs their head read.’

RE-EXAMINATION BY CHARLOTTE KILROY KC – 3 NOVEMBER

Ellie returned a few days later on the morning of 3 November 2025 to answer questions put to her by her own barrister, Charlotte Kilroy KC.

Those questions went back over some of the topics touched on in her first day’s evidence, examining in more detail the relationship Ellie had with Thomson, before and after his deployment ended.

Kilroy began by asking Ellie whether she would have agreed to have a sexual relationship with Thomson if she had known that he was an undercover police officer. Ellie was categorical in her response:

‘Absolutely not. No. Not a chance.’

Ellie saw Thomson once or twice a week, and they were in contact via regular texts and calls. Kilroy asked what they would talk about:

‘How your day went, what have you been up to, planning on when we were next going to meet up, what we were doing next… caring, nice, relaxing, romantic, nothing too heavy. We didn’t have deep and meaningful conversations over text messages.’

Ellie explained that Thomson was her first proper relationship and her first love, and she saw it continuing long term, with a possibility of moving in together in the future.

But Thomson contacted her in early 2002 and asked her to go for a walk around the block. He told her that his ex-partner had a new partner and this new partner had a new job in San Francisco. They were taking his children, so Thomson was going to move too. This was a lie to cover up for the fact that his undercover deployment was ending and he needed an excuse to disappear from her life.

Kilroy pointed out that a move like the one he described should have taken a long time to organise. Ellie agreed. She said she was surprised how fast it progressed. He gave the impression it was the first he knew about it, and she imagined she’d have at least six months before he left. It went a lot quicker than that, and she wasn’t happy about it, but she didn’t want to make him feel bad.

When he left, buying her the motorcycle course and writing the note saying ‘see you in the south of France’, she took that as a positive sign they would keep in touch.

The email he sent six weeks later confirmed it:

‘It showed that he made an effort and he said some lovely things in it, so I printed it out and I kept it… it suggested that he still cared quite deeply and didn’t want to let the relationship go. And wanted to meet up and, like, there was no way I wasn’t going to meet up with him.’

CURATING SEXUAL INTEREST

Kilroy took us to that email [UCPI0000038289] to look in detail at how Thomson makes clear he is thinking about her body in a sexual way:

‘Actually unless I get my ass (that’s the local colloquialism for arse in these parts – oh, and that’s just reminded me of yours but moving swiftly on)’

He compliments her about her intelligence and wit, then refers to her insecurities and lack of confidence, and talks about still knowing each other when they are ‘old and grey’.

Ellie explained that the email made her feel differently about the end of the relationship. It suggested he still cared about her, it wasn’t really over and they would stay in contact. She felt something more might happen in the future.

In fact, they met up again within a few months, and it was like a date:

‘It would have been the two of us, we would have gone out, maybe dinner, maybe drinks, intimate conversation. Basically, whenever we met up it was like we’d picked up where we left off… Touching, handholding, kissing at the end… He would walk me to the train station, wait until my train was coming, we would have a kiss goodbye and then I would go to the platform and catch a train.’

They emailed every couple of months, and met up about once a year. She thought he was living in the USA and those were the only times they could see each other. She didn’t know at the time he was living in the UK as a serving police officer. Knowing that now makes her feel a bit of an idiot.

‘But I would never in my wildest dreams have thought that it was all a lie. That would never have occurred to me.’

Ellie moved to Australia in 2005, but the contact with Thomson continued. She would visit the UK every 18 months or so, and she would meet up with Thomson almost every time. There were hundreds of calls and texts over the years, which were always caring and romantic in tone.

Again, Kilroy took us through several of Thomson’s emails in detail, particularly Thomson’s expressions of sexual frustration [UCPI0000038281]:

‘I had a truly wonderful time. Even seeing you so briefly brought it all back. As for the attraction I so obviously still feel for you; suffice to say I’ve never felt as frustrated as I did knowing you were in a hotel near Heathrow without a chaperone whilst I was stuck in Scotland!’

Thomson makes multiple sexual allusions, describing how much he is still attracted to her. He refers to a time they had sex, and indicates that he is fantasising about her in uniform.

Knowing the truth about Thomson makes these emails extremely uncomfortable and unpleasant. He blames her for leaving him in sexual frustration, and asks over and over for photos of her naked or in lingerie in a self-confessed ‘tirade of sexual longing’ that went on for more than a decade.

He told Ellie that she was the only cure for his sexual frustration and complained that she was ‘half a world away’, and describes himself as ‘sordid’ talking about her ‘bare naked arse’.

Ellie says all his emails were like this and that made her keen for a sexual relationship with him again. She is clear the relationship was not platonic. It was only because they were a long way apart that it wasn’t sexual, and you wouldn’t talk like that to someone who was just a friend.

‘It stopped me moving on, because there was still that connection there. And it was still like a very strong reminder of the relationship and the sexual relationship that we had, and it was still suggesting that that could continue in some form or another.’

Ellie recalled a time that they met up and kissed on Box Hill:

‘We were sitting on the hill and I was in front of him and he had his arms around me and I sort of leant back and we had a kiss. And then there were these two men that walked past and they looked over at us – quite clearly at us – and laughed. And I thought it was odd. And I mentioned it at the time, I was, “did they see us or something?” And he said, “oh, they must have done”. In hindsight, I think they knew him.’

Kilroy points out that in an email from June 2014 Thomson refers to thinking of Ellie hanging around his office naked. Given where he had worked that is a deeply unpleasant thought.

When she visited the UK in 2015, Ellie met with Thomson at a hotel near Heathrow where they had sex. The initiative came from him. She now knows that this was after he had come forward to the Undercover Policing Inquiry.

The emails continued, but that was the last time she saw him before she spoke to him on the phone, in 2018, and he told her he was an undercover officer.

‘He sort of blurted it out quite early. He explained that there was an inquiry, that someone might be in touch. He asked me if I still had my old email address.

He told me that he couldn’t tell me a lot of information. He said he was willing to talking about it and tell me what he could. He said that they will probably tell me his real name, but his first name was James…

He said things were different today than they were back then. But he definitely did not think he’d done anything wrong.’

He did not apologise to Ellie for deceiving her for 18 years, instead telling her ‘my private life is my private life’.

Thompson told her someone might be in touch, specifically that ‘a sweaty English man in a raincoat talking about the Inquiry’ might visit her. She wasn’t sure if he was being light-hearted or resentful. She found the prospect disturbing. He told her not to let Wendy know the truth as she would be angry.

Ellie pointed out that when Thomson first appeared, many of the animal rights activists suspected him of being an undercover officer:

‘As time went on, I think they decided that he couldn’t be – he was just a little eccentric.’

Ellie’s first reaction to Thomson’s call was similar to that of many other people deceived by spycops into having close personal relationships. She didn’t want to betray him. She still felt their bond was genuine. It took her a while to accept the reality. It was a process, and she is annoyed with herself now that she realises it was all a lie.

When Thomson contacted Ellie again to say he knew she’d been in touch with the Inquiry she felt sick.

Q. Why did you feel sick?

A. Because he knew. And I hadn’t expected him to contact me and then I had this – it was quite confronting and just there’s a whole range of emotions that go on. I was still at that point, I think, feeling a certain aspect of guilt, I suppose. Although that wasn’t logical and I knew it wasn’t logical, I still felt quite intimidated by the text. There was no reason, there was nothing intimidating in it, but I felt quite intimidated by it… Because he knew and I didn’t know where that put me.

For a few months after I just went down rabbit holes. Like I can’t explain the need to know, where you need to find out.

One of the things I looked at is what kind of personality would be an undercover officer and from what I read it’s quite similar to con artists and they tend to have this sort of personality trait, which means they are able to lie, they don’t feel guilt lying and they don’t feel empathy.

So they tend to have quite strong straits of psychopathy, narcissism, Machiavellianism, all of that kind of stuff and the problem with that is people like that do not like being confronted, do not like being called out on their behaviour and it is very common for them to want revenge. So that’s something I am very aware of and he knows where I live.

She is convinced that he is still keeping an eye on her. She feels sure there are going to be repercussions for her giving this evidence. As a result, Ellie has closed off from people. She feels her home is bugged. She doesn’t keep a phone on her, and she takes different routes to work.

It is clear that talking about these impacts deeply upsets her and, as at her previous hearing, Sir John Mitting intervened to say:

‘I appreciate that this is not easy for you. But if you would like to continue to finish I am more than happy to do so, or to rise for a bit if you want to.’

Ellie simply said that she cannot imagine things will be any different in the future, and she had nothing else to add.

With that, her evidence ended. She was thanked by Mitting.

There are two new names on the list of known officers from Britain’s political secret police; Christine Green and Bob Stubbs.

There are two new names on the list of known officers from Britain’s political secret police; Christine Green and Bob Stubbs.

Guest blogger Harvey Duke with the view from Scotland:

Guest blogger Harvey Duke with the view from Scotland: