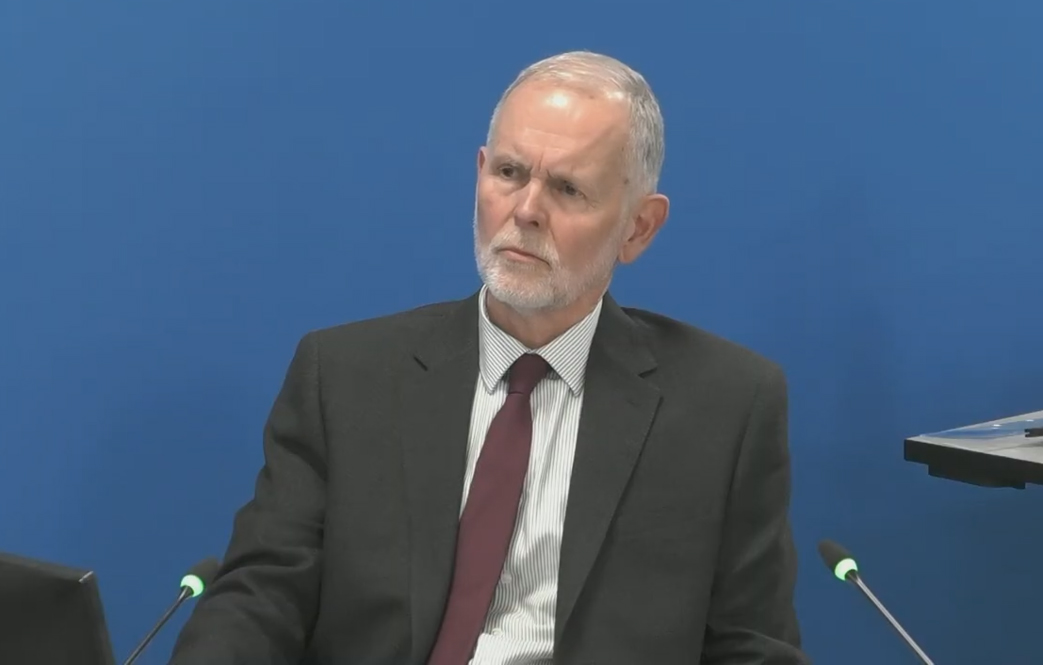

UCPI – Daily Report: 28 November 2024 – ‘Jacqui’

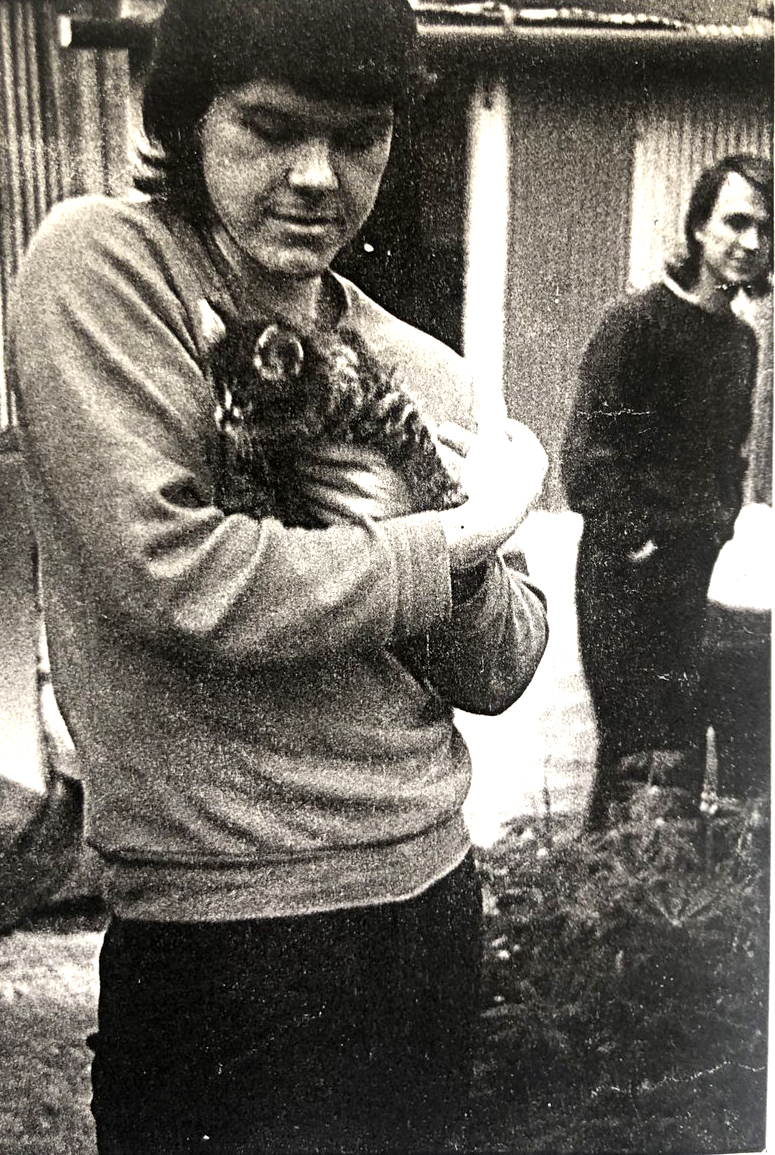

Spycop Bob Lambert whilst undercover, 1987 or 1988

On Thursday 28 November 2024 the Undercover Policing Inquiry took evidence from a woman known as ‘Jacqui’.

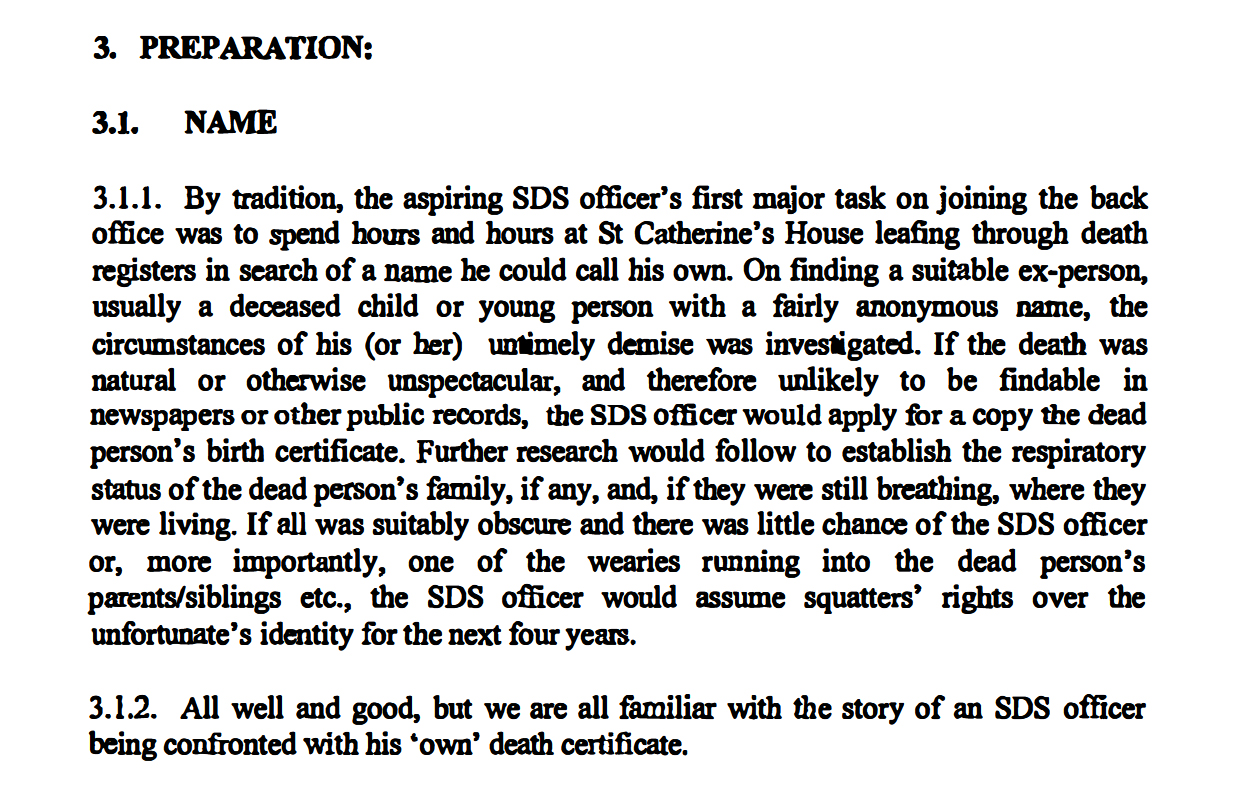

She was an animal rights activist in the 1980s and was deceived into a relationship by undercover officer HN10 Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’. They had a child together, even though Lambert knew he’d abandon them both when his deployment ended a couple of years later.

Jacqui was questioned by Daisy Monahan for the Inquiry.

This is a long report. You can use the links below to jump to specific sections:

Activism

Leafleting and hunt sabbing, the ALF’s Wickham raid, Lambert creating division and suspicion

Meeting Lambert

Lambert’s activism and undercover persona, their relationship, his other secret relationships, Jacqui’s employment

Parenthood

Their planned baby, the birth, Lambert avoiding being named as father, their move to Dagenham, and the relationship’s end

Debenhams

The plan, the arrests, Lambert leaving

Impact

The effects of Lambert’s desertion, hardship, discovery of the truth and untold ire for the Met

The UCPI is an independent, judge-led inquiry into undercover policing in England and Wales. Its main focus is the activity of two units who deployed long-term undercover officers into a variety of political groups: the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS, 1968-2008) and the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU, 1999-2011). Spycops from these units lived as activists for years at a time, spying on more than 1,000 groups.

This hearing was part of the Inquiry’s ‘Tranche 2 Phase 2’, which mainly concentrated on examining the animal rights-focused activities of the SDS from 1983-92.

Click here for the day’s page on the Inquiry website.

ACTIVISM

Jacqui was inspired to become active in animal rights campaigning when she saw The Animals Film on Channel 4 in 1982. She was 20 years old and living alone in Hackney, East London.

The Animals Film cinema poster

The animal rights movement was growing at the time, with lots of young people getting involved. Jacqui recalls going to protests at several places around London.

One was an open market in Club Row, off Petticoat Lane, where puppies and kittens were sold. There was also the Leyden Street chicken slaughterhouse nearby, where customers selected their own bird and watched it being killed.

She met people who had been campaigning for years, and one of them told her about East London Animal Rights (ELAR) and hunt sabbing.

EAST LONDON ANIMAL RIGHTS

ELAR was a small, informal group. Meetings were ad-hoc and held at people’s homes. They would usually be attended by fewer than ten people, mostly women. Those involved understood that their aims were to let people know about how animals were treated. They often gave out leaflets in shopping centres.

Asked about her membership of these groups she explained that it wasn’t so formal – ‘you didn’t sign in!’ -they were loose aggregations of people who did different things together.

Jacqui stresses that she went to numerous meetings, and they were so informal that they often didn’t have a group name. This runs contrary to the police reports in which officers, from their uniquely regimented perspective, named and described groups and the supposed hierarchies within.

In his witness statement to the Inquiry, Lambert described Jacqui as ‘a leading member of ELAR’, but she says this isn’t true at all:

‘I was one of six or whatever that turned up. No. There wasn’t an East London Animal Rights to be a leading member [of]…

It’s like they are trying to put a square peg into round holes and they are forcing it in to make it fit their narrative. Because, yes, news to me. This is all news to me, that we belonged to East London Animal Rights.’

Asked if there was any sort of group mission statement she scoffs:

‘Mission statement? It was more like Carry On Animal Rights.’

As well as her day job in the City, Jacqui worked in pubs a few nights a week in order to make ends meet:

‘Different pubs I have worked in. I got sacked from every single one of them. I am not good at customer service.

And, yes, so I used to do two or three nights in a pub. Because working in a pub, you could usually get someone to buy you – this is how bad, this is what I am talking about – is that you could usually get somebody to take you out. That means you get to eat that night. And yes, that was the point.’

Jacqui became very committed to animal rights, and would prioritise hunt sabs and demos over casual shifts in the pub, even if it meant she got sacked for refusing work.

Asked to describe the demos outside Leyden Street slaughterhouse, Jacqui recalls that by the time she joined in, these protests had been going on for years – she says there were maybe 10-20 protesters there. They would be chanting and shouting slogans at customers.

She found the slaughterhouse profoundly distressing:

‘I used to end up in bits – really, really upset’

There was no violence or police presence, although the slaughterhouse staff would wave their knives and threaten them for putting off customers.

They were usually there on Sunday mornings for a few hours until the market closed at lunchtime.

This controversial slaughterhouse was eventually closed down. The council shut down the sale of puppies and kittens in Club Row too.

Asked if ELAR ever did ‘oversee or organise any sort of direct action’ – the Inquiry still not grasping the nature of these activists – Jacqui was clear that there was no liberating of animals, nor serious criminal damage.

She did admit she ‘might’ have sprayed graffiti on occasion, recounting one time she was passing a railway line in Hornsey:

‘Lots of advertising hoardings on it, but then there was a great big blank space where they had not renewed the advertising thing. And I thought, blank space. So I must have had, or someone must have had spray, I really can’t remember…

We would have done the A with the circle, something like that. I have only recently found out that the A means anarchist. I used to think it meant animals.’

In her statement to the Inquiry, Jacqui describes the animal rights activist movement she worked with:

‘It comprised compassionate tender-hearted people who simply had a deep fondness for animals. They would take in stray dogs or do other animal rescue work. Some were middle-aged or elderly women who would get together for tea and cake. Others were harmless eccentrics. None of them posed any threat to the state.’

Sylvia Martin used to host some of the meetings. She was older, around her 60s. An ex-actress and model, Jacqui remembers her as glamorous, flamboyant, posh, outspoken, and absolutely no danger to anyone.

Jacqui laughs at the description of Sylvia’s Fur Action Group as an ‘offshoot’ of ELAR:

‘You are talking as if we were a corporation, you know, with a financial officer and – alright, call it an offshoot. Or a cell. Sometimes you call them cells, don’t you? We were a cell.’

This drew much laughter from the public gallery.

FUR ACTION GROUP

Spycop HN11 Mike Chitty ‘Mike Blake’ undercover in the 1980s

We’re shown a spycops report written by HN11 Mike Chitty ‘Mike Blake’, dated 12 December 1984 [UCPI0000014820] about the activities of the Fur Action Group.

It names Jacqui as one of a number of people who had protested at the Leyden Street market and then, having seen a newspaper article about a fur fashion show at the Cafe Royal, went there and held a sit-in.

Asked if it was peaceful, she says she can’t clearly remember it so, given that disorder would have stuck in her mind, she’s confident it won’t have gone beyond ‘a bit of verbal’.

Chitty reported on Jacqui numerous times. Despite her now seeing contemporaneous photos, she doesn’t remember him at all.

He’s described one of the women on the demo as ‘attractive’.

Jacqui mentions that she herself is described as ‘reasonably attractive’ in another report and, after an aside to say she was actually gorgeous at the time, she is blunt:

‘I am angry that women are described by the way they look. And when they get to a certain age they are invisible. So you are either a bit of totty or you are invisible. Otherwise, you have no role.’

HUNT SABOTEURS

Like many young animal rights activists, Jacqui became a hunt saboteur:

‘You can do something direct, and obviously I am on the right side of history because hunting is illegal now, or it is supposed to be.’

Her prime motivation was to save foxes, but she also highlighted the mistreatment of hunting hounds.

She was part of a group that targeted the Surrey Union hunts which she said rarely caught foxes. It seemed that trying to fight hunt sabs was more of a sport to its supporters and terriermen:

‘It come as a shock to me how physical it is. How you are running really, really, round big swathes of land and those swathes of land might have posts, they might have hedges.

You have to get across those, and obviously you have loads of horses coming towards you, which is quite scary and therefore, yes, you got to be fit – and I quite liked that out in the countryside. Yes, I really liked it.’

SOUTH EAST ANIMAL LIBERATION LEAGUE

She went out sabbing with South East Animal Liberation League (SEALL), and says that they – another loose group of about ten people who were good friends, not ‘members’ as such – were more focussed on direct action than ELAR. As well as sabbing they would liberate animals:

‘I didn’t consider myself a member of any group. It’s the way you have structured it in terms of for the Inquiry is to put them into groups. But I would never have described myself as I am sort of a ‘member of’ this – it’s not like being member of a knitting circle or a member of the Women’s Institute or something like that. It wasn’t like that.’

Jacqui went sabbing most Saturdays from 1982 to 1985, until she was heavily pregnant.

She was wholeheartedly committed to helping the animals, but she also spoke movingly about how the social aspect was meaningful too, especially for someone who had been estranged from her family since she was 17:

‘Suddenly I had a group, and a group of friends who cared about and had the same values as me. So, when you sort of feel like you’re the only person who thinks like that, so there must be something wrong with you, because no one else seems to care, you give out these leaflets and they just get dropped on the floor. No one seems to really care. You try to make them aware of what’s going on and they are not interested.

And then you meet a group of friends, of like-minded people, similar age, and from that it’s going to be a social life attached to it.

So I was like this little urchin, sort of – I was completely solo from 17, with no education whatsoever. I didn’t go to school when I was after 15… I didn’t have any education to back me up, to progress in any way. And they filled a void for me, yes. They were friends.’

She says there was little in the way of security precautions among the group. There wasn’t much to hide – and they couldn’t bug her phone because she didn’t have one. Anyway, hunt sabbing was public and lawful:

‘I hadn’t been to law school at that time, like I have now… I think we all sort of assumed it was legal. You wouldn’t believe it by the way we were treated by the police, even when we were assaulted.’

She remembers the sabs making up spray bottles of citronella and using this to put the hounds off the scent of the fox.

She says the hunts’ terriermen were the ‘real muscle’ – intimidating, violent ‘meat-heads’ whose role was to send dogs down holes after foxes (and sometimes badgers, which were supposed to be a protected species) and ‘tear them to pieces’.

Jacqui described with revulsion the hunting tradition of ‘blooding’ – when a child first goes on a hunt, the blood of the killed animal is wiped on the child’s face.

Sabs were ‘seen as the plebs, scumbags’ whereas the hunters were part of the Establishment, which succeeded in delaying the hunting ban for years.

VIOLENCE AGAINST HUNT SABS

Hunt saboteurs and hunt supporters face to face. Pic: Andrew Testa

The hunt sabs were frequently threatened by hunt supporters. Women hunt sabs were threatened with sexual assault – she recalls that this always ‘loomed over you’. Supporters would also drive vehicles directly at hunt sabs.

She recalls one incident when she was caught. One of the hunters fell from his horse. The sabs saw hunt supporters pointing at them, and ran away. Jacqui was separated from the others and caught by at least four of these men. There was more than one on each limb and they threw her into a lake.

It was a freezing winter’s day, the deep water was so cold that it stung on contact, and the men who threw her didn’t even know if she could swim. She couldn’t get out and the men just walked off laughing.

She was rescued by other sabs. Soaking wet, she walked with them back to the pub where the hunt had started from. The landlord told her that she deserved it, so they had to walk on to find somewhere to shelter. It was a long journey home to London.

‘It was part of a game to them… there was quite a few times that they never killed a fox. But sometimes that was because they was concentrating on hunting us. So it is almost like they sort of enjoyed it. They used to have a big smile on their face when we turned up.

She said sabs were constantly attacked, frequently with horse whips that left physical injuries. She notes that almost every attack she can think of happened to a woman sab.

‘I was whipped loads of times. They got a thing about whipping, those sorts of people. Strange, isn’t it? Public schoolboys and their whips.’

Asked if she reported it to the police, she patiently explained that police were never interested in violence against sabs:

‘We were the baddies, according to them.’

She explained that the police would be on good terms with their local well-to-do hunters. She would see police mingling with hunters as they convened. It was plain that they were firmly on one side:

Q: The police didn’t come to your aid, is that right?

Jacqui: Well, Bob did. But I didn’t know he was a policeman until 2012.

Asked if sabs were ever violent to hunters, Jacqui points out the impracticality of taking on mounted shotgun owners:

‘They were on great big hunting horses that are bred especially for that! Have you seen the size of them? They are on those and we are not.’

THE SECRET ORGANISER

As to whether the sabs ever brought weapons or organising violence, she refers to ‘He Who Can’t Be Named’ (someone who came to sab the Surrey Union Hunt, whose identity is protected by the Inquiry) getting hold of walkie talkies for the sabs to communicate with each other. Those and the bottles of citronella, that was as organised as they got.

She got to know ‘He Who Cannot Be Named’. She describes him as intelligent, charismatic, and with an air of authority.

He gave evidence to the Inquiry and said he only went to the Surrey Union hunt two or three times. Jacqui incredulously dismisses his claim:

Jacqui: Sorry, I was going to swear then. Rubbish.

Q: How many times did you see him?

Jacqui: Every time. He’s the one that got the walkie-talkies and everything. As if we’d be organised enough to do that!

She says he was the ‘self-appointed’ press officer of SEALL, arranging their demonstrations, sabs, and raids to liberate animals:

‘If you wanted to have arrangements for something then he was the person who had all the arrangements and he’d be the one organising it. So if you had a question about it, he was the person you would go to.’

Jacqui was friends with his girlfriend, and they tended to each have one of the group’s walkie talkies. As an illustration of how seriously he took everything, she recalled him angrily telling her off for not saying ‘roger and out’ when ending a walkie-talkie conversation.

She remembers Ronnie Lee – an animal rights activist who’d received a long jail sentence – wasn’t around at this time, and He Who Cannot Be Named said he wanted to ‘take it further than what Ronnie Lee did’.

In his evidence to the Inquiry, He Who Cannot Be Named said his role spearheading SEALL’s actions was earlier, in 1983 and early 1984. However, Jacqui remembers introducing him to Bob Lambert, and she only met Lambert in the summer of 1984.

At the time, Lambert was in a relationship with a woman known as CTS, which ended when CTS went to university in September 1984.

Just like He Who Cannot Be Named, Lambert has his own version of the timing too – he says he first met Jacqui later, at a demo in the winter at the end of 1984! She’s absolutely certain this isn’t true either. Not only was CTS gone in September, but she can remember she was wearing summer clothes when they met.

As for He Who Cannot Be Named, Jacqui is confident he was sabbing much later than he claims:

‘I would put him there until I stopped going, which would have been some time in mid-1985’

She can pinpoint that date as she stopped due to being pregnant with Lambert’s child, known as TBS.

Jacqui is sure that she introduced He Who Cannot Be Named to Lambert, but says the two men didn’t become friends. He knew she and Lambert were a couple, and he regarded her as a friend.

In both his written statement and his live evidence, He Who Cannot Be Named says he has no recollection of Jacqui whatsoever. Is she surprised about this?

‘Oh, no, no, no! I am not surprised. Because he says he doesn’t remember anything about anything about anything!’

THE WICKHAM RAID

Though she’s confident she introduced Lambert to He Who Cannot Be Named, there’s an element of doubting her own memory because of the extent of Lambert’s deceit and abuse:

‘That’s what I have always believed. But remember there is a lot of things I believed and they are complete and utter bollocks.’

She elaborates that the fact of having TBS and, since they discovered Lambert’s true identity in 2012, supporting TBS in his desire to get to know Lambert means that she’s had her memory altered by more recent discussions:

‘I still see Bob Lambert now. And I have seen him since 2012. So obviously we have had lots and lots and lots and lots, hours and hours and hours of conversations about things then. So that can mean sometimes your memory – there is the memory of what I have from back in the 1980s but then that is obviously going to be tainted…

So sometimes it can be almost like a false memory, because what you are remembering is what you know now, really.’

Jacqui was approached on a hunt sab by someone who was recruiting for a raid on Wickham Laboratories, an animal research and testing facility in Hampshire. It was what she’d yearned to do all along:

‘I wanted to rescue animals. That’s it. You know, I am completely non-violent and I’ve just got this empathy for children and animals that are just like, yes, vulnerable. So, yes, I would have been up for it.’

We’re shown a Lambert police report, dated 23 October 1984 [UCPI0000014858]. It says that He Who Cannot Be Named is organising an unspecified action for 28 October, and Jacqui will be participating. This is the Wickham raid, which became notorious for the severity of sentences meted out to its participants.

He Who Cannot Be Named has told the Inquiry he may have known that an action would happen at Wickham, but he had no part in organising it. Jacqui says that on the contrary, this is nonsense and the information in Lambert’s report is correct.

As for He Who Cannot Be Named, she says:

‘I am a bit scared of him actually… If anything happens to me from now on, you all know

where to look. If something happens to me.’

Lambert’s police report says that Jacqui planned to travel with a friend who had a car, after further briefing from He Who Cannot Be Named. She was invited to a meeting point, but she wouldn’t have known the target location, and wouldn’t have asked, and knew not to tell anyone. This security culture was well established. As a ‘foot soldier’ she wouldn’t expect to know where she was going until she actually got there.

It seems that Lambert’s report may have been based on information Jacqui had given him. She’s distraught at the possibility that she might have inadvertently aided the imprisonment of people she cared about, who were taking action she supported.

She says she has talked with Lambert about it and he’s told her this is not the case:

‘He assured me that there was so many spycops out there. He said it was the sort of leakiest operation ever. There were so many reports that this was going to happen, that he didn’t need to be the person. But he might have been saying that to try to make me feel better…

It is the reason why they were with us, was to get information, and unknowingly we were giving information because we were in intimate relationships with them.’

She explains that Lambert was older than her. He was manipulating her trust and therefore she wanted to share things with him. She feels that she probably did give him the information about Wickham. She says sorry. Monahan, the lawyer representing the Inquiry, tells her not to worry, but she replies:

‘No, I meant sorry to all the activists.’

LAMBERT’S REACTION AND ESCALATION

Asked about Lambert’s reaction at the time to her telling him about the plan, she gives significant insight into his undercover persona:

‘Well, he didn’t go “Ooh, I am a cop”. Obviously, he reacted how he had been trained to react…

He would have wanted to get involved. He would have liked all that stuff. Because he used to mock that all I did was going to those meetings… that, you know, bunny hugging wasn’t going to get anywhere. And also he said he was an anarchist and, therefore, he didn’t believe in the system.’

At the time, she countered by highlighting to him the Labour Party’s promise to ban fox hunting (which it eventually did). But Lambert retorted that it wouldn’t affect vivisection or other forms of animal abuse:

‘I thought he lived off the grid and at that sort of time I would have been passionate about him then. I thought he was wonderful. Especially as he was that much older than me. And I have never had a good father/daughter relationship.’

This dynamic, combined with Lambert’s overt exhortations, encouraged her to feel she was ready to participate in more radical action. She says He Who Cannot Be Named had a similar effect on her too.

We’re shown a police note of a phone message from Lambert on the morning 26 October 1984 [MPS-0746925], two days before the raid, saying Jacqui and her friend were withdrawing from the action.

RAID CONFUSION

Jacqui says that she’d long believed she was on the Wickham raid:

‘I always thought I was on Wickham, you know. I always, in my memory, until 2012, I thought I was on Wickham. And I obviously was getting that mixed up with something else that I was on. Because Bob assures me he made sure I didn’t go on Wickham.

He said he can’t remember what, but he made sure that he distracted me with something else so that I didn’t go near Wickham because he knew that it was going to be – the police knew about it…

‘And I did ask him what – how did you manage to do that? Because I was passionate about it. And it would have been my first proper action, apart from sabbing. So, yes, I asked him what and obviously he can’t remember. Bob’s got a lot of plates to spin as we now know.’

It does sound like it might be Lambert rewriting her memories but, as she describes the event, it becomes clear that she is confusing Wickham with an abortive raid she went on:

‘I was on an action where you meet and then you go to one place and then you go to another place and all that. And I was. And we finally got to our final destination. I can’t even remember what part of the country. As I have said, I have gone all these years thinking it was Wickham…

We got to this place which was apparently a laboratory. I thought I would rescue animals but there was no animals in there. But what there was, was some sort of equipment that like that scientists use where they put their hands in like gloves and I suppose handle the animals. It was like a glass thing where I suppose you would have animals in there and you do your procedures on it…

I found it really chilling, just seeing the equipment even though there was not any animals there. And I think we damaged the equipment. But an alarm went off… then we all had to leg it’

This description of an empty lab cannot be Wickham, which was very much an active vivisection laboratory at the time.

We’re next shown a Lambert report dated 20 November 1984 [UCPI0000014769]. It encloses a SEALL leaflet asking people to donate to the Wickham defence fund, helping families to visit imprisoned activists and to buy them vegan food.

Jacqui remembers fund-raising by going around the pubs collecting:

‘Men would say I’ll give you money for a kiss’.

OSTRACISING AN ACTIVIST

Lambert’s report goes on to say that several activists think there was a security problem, and that one person is accused of giving names to the police:

‘A hitherto energetic and respected campaigner is now shunned by the whole animal rights movement.’

Regarding the same person, a further Lambert report dated 3 December 1984 [UCPI0000014790] says:

‘Defending himself against the charge of giving names to the police, he claims that police officers obtained names of animal rights activists from private correspondence seized at his home address at the time of his arrest.

However, he is a demoralised man, much frightened by the prospect of a prison sentence, unlikely to return to the position of trust and respect with which he was once held.’

Jacqui is still really distraught by the man’s plight:

‘This is shameful… he was just the loveliest gentlest man. He probably wasn’t very bright. Very vulnerable. And he was just a really lovely empathetic man and he wanted to please and he certainly thought Bob was wonderful.

I was just quite close to him because he was so gentle and such a sort of honest soul, you know. A beautiful soul.’

She says that Lambert told her at the time this man’s address book had got everyone arrested, that he was an informer and that she wasn’t to speak to him anymore. She then told others the same story.

Now she wonders whether there even was an address book, or whether it was Lambert covering his tracks as the mole, and sowing discord among a group the spycops didn’t like:

‘We were served up a patsy’

She really liked the man and didn’t think he would have spoken to the police. She trusted him with a key to her flat, and the feeding of her cats – ‘they were like my babies at the time’ – and she also saw that his compassion for animals, shared with the group, was his social life as well as his moral concern.

She says that when she found out the truth about Lambert in 2012, concern for this man was among her first thoughts.

Jacqui says he was a broken man, completely devastated. People were horrible to him, it was the worst accusation possible. Lambert would have known all this. She is very, very angry.

CREATING DIVISION

In her witness statement she says it’s just one example of Lambert fostering division among the activists. Asked about other instances of him sowing such discord, she says:

‘He was always telling me that some people couldn’t be trusted. So he sort of made me paranoid. He would always tell me that this person was a wrong ‘un, and this person wasn’t right, and you are too trusting, and you know – he was always stirring the pot.

It’s why loads of groups broke up, because when you get to the root of it, these cops were there and they were making us paranoid that people that we thought could be trusted couldn’t be trusted, and no one could be trusted.’

She reflects on the extent of the spying on her, and the exaggeration and tone of the police reports:

‘You read some of this stuff, it makes me sound like I am Mr Big on top of a big cocaine ring, you know, organised crime group. You know, I am second in line in ISIS or something. I was just a dopey bird, right? A dopey bird who was doing her best and trying to survive in a world full of sharks. Full of male sharks.’

MEETING LAMBERT

We’re shown the first Lambert report that mentions Jacqui, dated 19 October 1984 [UCPI0000020318]. Jacqui confirms she was in a relationship with Lambert by this time (though he claims it happened later).

He says that through her work at a financial company she got hold of secret financial information about multinational chemical firm ICI and passed it to the Animal Liberation Front, enabling a raid on an ICI research centre.

Jacqui dismisses the claim as ‘ridiculous’:

‘Look at my age and what a junior position I would have had! I worked for temp agencies, so if I was there at this place I was there as a temp. You know, they didn’t invite me in and start showing me all their financial documents.’

She says she might have said something like it to try to impress Lambert but if she did, he should have known full well that she wasn’t going to be privy to such information.

As for passing it on, the Inquiry asks whether it has anything to do with an April 1984 raid on an ICI facility in Alderley Edge, Cheshire, claimed by the Northern Animal Rights League:

‘Never heard of them.’

She points out that she didn’t even have a phone at the time. When Monahan inquires further about whether she would have been in communication with the group, Jacqui interrupts:

‘What would I have had? Crystal balls?’

LAMBERT’S TWO PARTNERS

‘CTS’ and Jacqui were around the same age as each other at the time, 19 or 20. Lambert didn’t tell Jacqui he was in a relationship with CTS:

‘Well, he’s not going to tell me the truth, is he? Because he was sniffing around me at the time. So he’s not going to be telling me that.’

Lambert says there was no overlap and he met Jacqui later, at a demo outside Hackney Town Hall, and describes Jacqui wearing an Avis car rental worker’s outfit. She says that happened, but wasn’t their first meeting.

‘I met him on the Essex hunt sabbing. But he tells me, no, it was that. And you know how truthful he is’

We are shown a Lambert report dated 20 November 1984 [UCPI0000014938] about a planned protest at the Hackney Town Hall, where Jacqui is reported to have told people to bring banners about the fur trade. Jacqui says that was a different event.

There is also a Lambert report of 3 December 1984 [UCPI0000014790] about demo outside a full council meeting at Hackney Town Hall, about the proposal that they adopt an ‘animal charter’ bringing in a number of measures such as a ban on animal circuses. Islington councillor Jeremy Corbyn had worked hard to get that passed in his borough, and they were hoping to get it replicated in Hackney – which indeed it was.

Jacqui is certain this is the one Lambert’s referring to. And she’s just as certain that she already knew him well before that.

She says that she only knew about his simultaneous relationship with CTS via other people.

LAMBERT AND BELINDA HARVEY

She hadn’t even known about the existence of Belinda Harvey, with whom Lambert had an additional relationship, until after the whole scandal came to light in 2012:

‘Never heard of her, nothing. Never mentioned it. Even though she had been to my house and I didn’t know, even though she had been with my son and I didn’t know.’

Once the spycops scandal was exposed, CTS came forward and made herself known to the lawyers representing women deceived into relationships. However, she has not taken any legal action, nor participated in the Inquiry.

‘She didn’t want to join the other women as an action, because obviously years ago, she’s got on with her life. She lives abroad now, she has a family and all the rest of it. She doesn’t want anything to do with it.

To tell you the truth, if I didn’t have TBS nor would I. I wouldn’t have put myself through all this for nothing. Because it certainly isn’t for money. The only reason I thought was because I have six foot of Bob Lambert’s DNA walking around who wants to be reunited with him.’

We break for lunch. Jacqui has been giving it both barrels all morning. It’s been impressive to hear her, she has no filter and is not holding back anything as she speaks very frankly and directly. And despite the horrendous subject matter, she’s introduced numerous notes of wit and humour too.

FIRST DATES

Jacqui is very clear when she went on her first dates with Lambert, and it was not in the winter as he claims:

‘I remember seeing him dressed for the summer… Not the first time, but like a date that I went on to a restaurant with him and things like that. I was definitely dressed for the summer’

Monahan points out that Jacqui’s witness statement says that, since speaking to Lambert in recent years, she’s come to believe they did meet that day in November outside Hackney Town Hall.

Monahan asks if Lambert has influenced her memory of when they first met.

Jacqui responds, very slowly saying:

‘I suspect he’s influenced me more than I will ever know about things, but yes… He still influences me. But yes. He still influences me.’

Lambert has told the Inquiry he became an active hunt sab in 1985, but Jacqui is certain he was involved before that:

‘He just suddenly started appearing everywhere. So I don’t know whether that was because of me or whatever.’

Monahan asks if Lambert was enthusiastic:

‘About sabbing or about me?’

Monahan is amused and says ‘good question’. Jacqui clarifies that it was both.

She never saw him get assaulted while sabbing, but he was a big man and hunters tended to go for women – and indeed, Lambert saw Jacqui being assaulted by hunters.

LAMBERT’S ACTIVISM

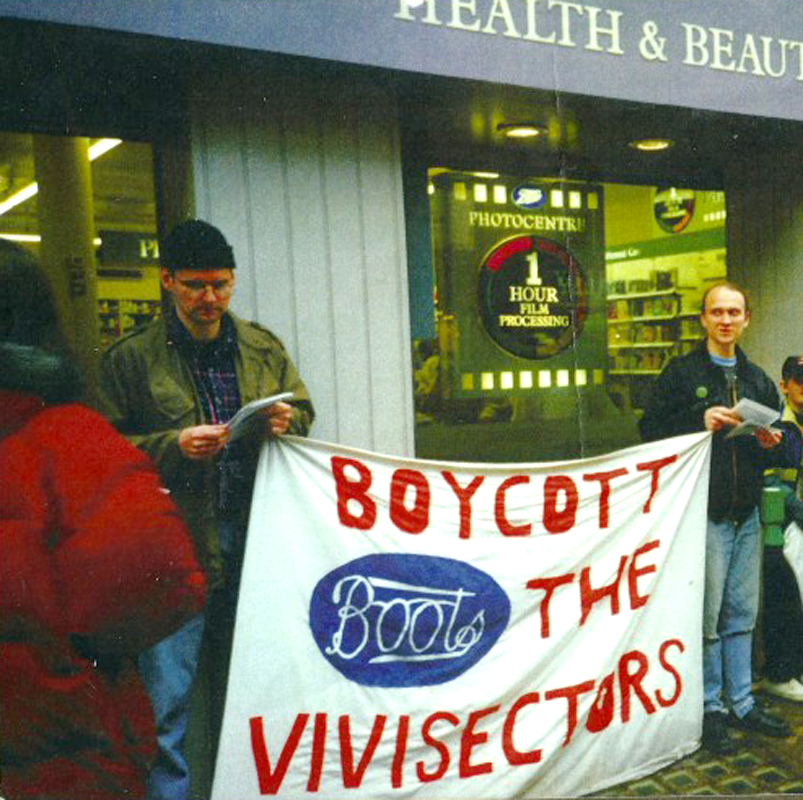

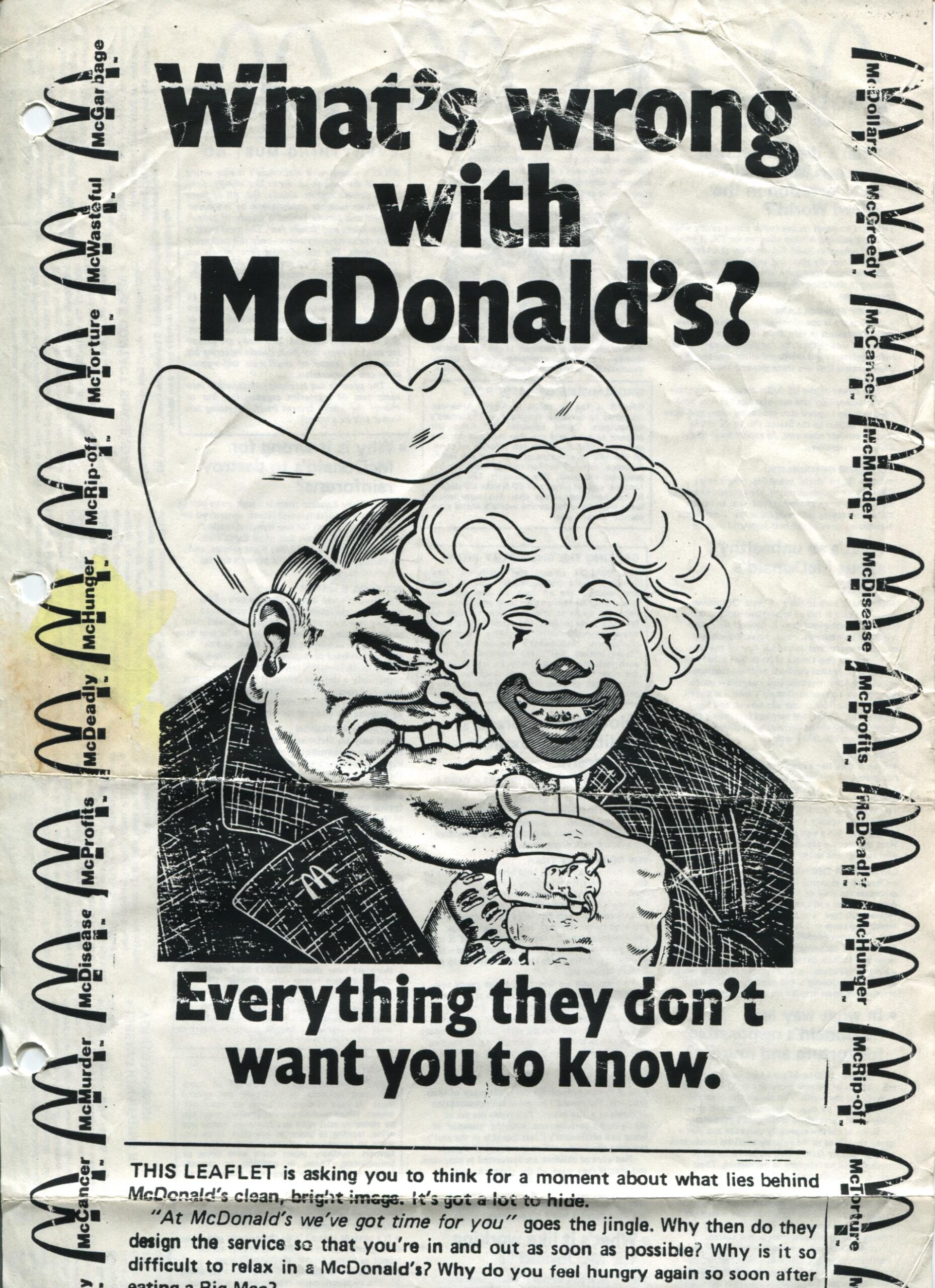

Paul Gravett (centre) & spycop HN10 Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’ (right) handing out the McLibel leaflet Lambert co-wrote. McDonald’s Oxford Street, London, 1986

Lambert seemed to be very knowledgeable about London Greenpeace.

Jacqui knew that he wrote some of the group’s leaflets and she thought he was very well-read about anarchism and the civil war in Spain, and ‘he seemed to be all up on the theory’.

She got the impression he was the brains of the group, though this was purely based on what he told her. She found him eloquent and persuasive.

She remembers being in awe of Helen Steel. She had heard about her reputation before meeting her, and saw her as some kind of ‘senior figure’ in the movement.

She went out leafleting with Lambert a number of times, outside the McDonald’s in the Strand. She recalls that Lambert didn’t just co-write the anti-McDonald’s leaflet, he wrote other animal rights leaflets too. She has a clear memory of one of these: the leaflet used for the demo at Murray’s Meat Market in Brixton, which featured an image of a human baby in a butcher’s shop.

She says that Lambert produced printed material for a number of Animal Liberation Front type of things.

Established animal welfare organisation British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection (now called Cruelty Free International) had a printer and would let other activists use it. Jacqui remembers that in return they used to help with the group’s admin and office tasks.

Much later, she followed the McLibel case from a very unlikely perspective:

‘I ended up working for the solicitors that were the lawyers for McDonald’s…

So I knew, it wasn’t just the McLibel case; anybody, no matter how famous they were, if they said something – obviously I know the names of people, really famous people, pop stars or whatever – if they basically said anything about McDonald’s, that’s it, you would get a desist letter straight away.

And I remember that everybody, no matter how wealthy they were, they would say sorry and desist. So they were really powerful.’

She has no idea how she managed to get that job – it may have been He Who Cannot Be Named or Lambert using their influence to ease her path.

Jacqui only went to one London Greenpeace meeting with Lambert, in 1984. He told her she’d find it interesting because there was lots of animal rights discussion:

‘That’s when he said the bunny-hugging thing. And he said if you come along to London Greenpeace, you can get properly involved because there’s a lot goes down there.’

She knew of London Greenpeace but hadn’t felt any affinity with it, and the meeting didn’t change that:

‘I had seen all that anarchist scene and it wasn’t for me. They were mainly quite sort of upper class. Well, they weren’t upper class. You got to remember, my mum and dad, underclass, right. So to me they seemed like they were just playing at it a bit.’

It was clear to her that Lambert was very involved and respected among the group.

RELATIONSHIP

Asked about her sexual relationship with Lambert, Jacqui is not able to pin down the exact date it started. He used to ‘make a beeline for me’ at events, she says.

Asked if she was a vulnerable person when Lambert targeted her, Jacqui deftly makes the distinction between how she felt then and a clearer, more objective view she has now:

Q: Would you have described yourself as vulnerable at that time?

Jacqui: No. I thought I had it all sussed. Like most young people do, I thought I had it all sussed.

Q: Looking back now, would you describe yourself as vulnerable then?

Jacqui: Yes.

She explains that she left home at 17 and was estranged from her family, with no support network. She lived in bedsits, lying about her age as she could only sign tenancies and get jobs if she said she was 18.

She said Lambert’s advances were appealing to her:

‘Because he was older. And because he seemed quite educated. I found that really attractive. It didn’t bother me about the money thing until later on.

And also, I thought I could change him. I thought, once he has a baby, he’ll settle down and he’ll get a proper job. And the amount of times I told him about getting a proper job.’

She points out the irony of her being unaware that he had the proper job of being a detective sergeant spying on her.

She doesn’t remember the chemistry between them, but says starting a sexual relationship felt mutual.

Jacqui describes Lambert as captivating when he talked to her about anarchism. He came across as an intellectual, and was different from other men she knew, who were only interested in making money.

Lambert dropped Jacqui off last when giving lifts home to a group of people. He might have asked her out then, it was all very quick, it might have been a day or two later at most.

They went to a Lebanese restaurant in Stoke Newington High Street which served vegan food (the same place Belinda describes him taking her, presumably). He was friendly with the owner.

Jacqui says that Lambert was a committed vegan, and she is repulsed at the idea of a relationship with a meat eater:

‘God, no! They sweat it and everything. No!’

In his witness statement, Lambert says the sexual relationship began after she invited him back to hers.

She confirms ‘might have done,’ with a smile.

Interviewed in 2013 by Operation Herne [MPS-0722577], an internal police investigation into spycops, Lambert is very cagey indeed and fumbles his language about the first date:

‘I think that people that knew me at the time say if anything I was probably a little bit reticent, you know. But again, you know, one thing leads to another, you know, you go to the pub and then oh well, erm, you know, especially the things like, you know, having a lift home’

Jacqui guffaws:

‘I take back what I said about he’s articulate and educated! I think my bulldog could have written that if you sat him at a computer for long enough!’

As for the substance of his rambling, that it was Jacqui who initiated the relationship:

‘I was such a scarlet woman, I was… No, he was like a rat up a drainpipe!’

LAMBERT’S LIFESTYLE

He told her about doing cash-in-hand work as a gardener and tree surgeon, working for rich people in Hampstead. He said he did enough to run his van and not much more because a frugal lifestyle fitted with his unmaterialistic ethos and left him more time to devote to activism.

She knew he was 32 years old. She visited his (cover) address in Highgate. She found his flat sparse, but not suspiciously so. He had a sizeable record collection, all of it at variance with her soul preferences:

‘He liked Leonard Cohen, which I used to call music to commit suicide by. He used to like all that.

And he also saw himself as Van Morrison. He loved Van Morrison. And if you look at what he looked like back in the day, there is a similarity. That’s kind of what he thought he was, cool and all that. So he had all his music there. He played The Doors. Not my sort of music.’

She asked about his name – why would your parents call you Robert Robinson?

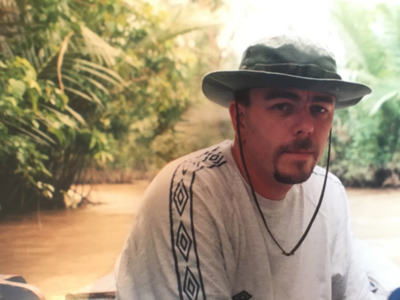

He explained that Robert was his middle name, he was actually Mark Robert Robinson. In truth, Mark Robert Charles Robinson had died aged seven of a heart condition, and Lambert had stolen his identity.

Shortly afterwards, she saw his driving license in the name of Mark R Robinson:

‘Probably in hindsight he left it out for me to see. I didn’t think at the time, I thought I was a right secret squirrel and I found it…

I didn’t mention that I had seen it. I thought oh, he was telling me the truth. He already said to me that was his real name and I thought, having seen the driving licence.’

She now realises it was him dealing with her querying his name.

The grave of Mark Robert Robinson whose identity was stolen by spycop Bob Lambert. Branksome cemetery, Poole, Dorset

Lambert told her that he already had another child, living in Australia. This was one of a number of lies he told that made her feel sorry for him. He also told her that his mother had died of cancer when he was seven years old.

This story of a troubled upbringing is common among spycops. It not only gives them a reason why their partners can’t meet their parents, it also makes their partners feel trusted and intimate.

Jacqui later learned that Lambert’s mother actually lived till old age.

Additionally, Lambert told her that his dad had dementia and wouldn’t recognise him, and that he was in a care home in Cumbria:

‘I don’t know if there was anything in Cumbria or that was just him disappearing to his family. I have no idea.’

The dementia was later used as an excuse to refuse Jacqui’s requests to meet her son’s grandfather, as his condition was supposedly too advanced and meeting her and TBS would only confuse him.

Jacqui offers a bit of advice to make sure you meet someone’s family and friends before you have a baby with them:

‘If they have no friends and they have no roots, there is a reason for that.’

Jacqui says that when she would nag Lambert for money or other things, he would look sad and defeated like a scolded puppy. Her mum told her this was because he’d never had a mother figure, and that she should go easy on him.

Lambert is ten years older than Jacqui, and Jacqui’s mum wasn’t much older than that, so they were close in age and would talk and connect. She told Jacqui to make allowances for him. It’s easy to imagine this is what Lambert intended from the conversations.

RELATIONSHIP ESCALATION

When it’s suggested that the relationship got intense quite quickly, Jacqui disagrees:

‘I wouldn’t say that. I always thought that he was more into me than I was him. You know there is always like an imbalance, even if people won’t admit it. And I always thought that I had the upper hand. I know that is odd now, but I always thought that I held that balance of power.’

They spent about half their nights together, and they were openly a couple among friends, displaying affection. He declared love for her and she reciprocated.

She believed they were in an exclusive relationship. She didn’t think he had the time to see someone else because they spent so much time together:

‘You didn’t keep track on people remember, like you do now. You didn’t have apps where you could see where someone was and things like that. I wish I did. I so much wish. I wish I hired a cab and said follow that car, follow that van, and found out where he went. But I didn’t.’

She recalls being a little envious of Lambert’s good friend and fellow London Greenpeace activist CTS. She believed that the pair were very bonded intellectually and didn’t want to believe they were in a sexual relationship. Lambert also downplayed any indications of the truth.

He told her that CTS returned to London some time later and met up with him, ‘to say goodbye’. It was when Jacqui was pregnant, and they had just been to an antenatal clinic. He told her ‘I want to be totally honest with you’ – Jacqui cracks up laughing at this, incredulously repeating the phrase twice.

Even then, he assured her it wasn’t sexual with CTS. Jacqui remembers feeling insecure, and him being very emphatic about it.

PICKING A PET TOGETHER

Lambert said he knew the person who was running a local cat rescue. They went there together and got Winston:

‘I picked him out, because he only had one eye and I felt a bit sorry for him. And also I thought she was going to have real trouble homing him because he wasn’t really friendly or anything like that. And he was really skittish, because I don’t know what had happened, I don’t know if he was semi feral or whatever.

I said which one, and Bob said as well, pick the one that no one else is going to want, because, you know, we will be all right. And that’s what we did… so we got Winnie Woo. Winston was his name, but Winnie Woo, we used to call him.’

A while later, Winston was hit by a car. The vet said the necessary surgery would cost £350.

‘He might have said it was going to be a million. I had no chance.’

But Lambert said he would pay the bill:

‘I was really worried because I thought if he’s finding that, that’s going to come out of something else we are going to need… I asked him loads of times where it was, but he said, just going “don’t worry about it, look just don’t worry about it”, and he wanted the conversation to finish. He didn’t want me to keep on about it.’

In hindsight, Jacqui realises that Lambert was never short of money.

JACQUI’S EMPLOYMENT

Jacqui worked as a waitress at a restaurant called School Dinners in Chancery Lane:

‘They had on the menu things like jam roly-poly, things that posh boys would have got at boarding school… around that time in the 80s, there was a lot of judges and everything – sorry! – ‘

She interjects the apology, realising the hearing is chaired by a former High Court judge, Sir John Mitting.

‘I did all sorts of jobs like that. I was a hostess at one point. I have done all sorts of jobs. I have been horribly exploited by old white rich men since I was 17. How do you think I survived? It wasn’t sex work. Never ever. I was a waitress’

She says Lambert knew about this work and seemed to find it titillating:

‘At the time I would never have said I was being exploited. I thought I had the upper hand. I thought, god, these blokes! The amount of tips I was getting and things like that, this is brilliant. These stupid fools giving me all this money just for caning them. My thinking has now been turned round and I can see that I was being exploited.’

This is especially distressing to hear, coming so soon after her comments about how she thought she held the power when Lambert deceived her into a relationship.

As the hearing takes a break, Mitting, has a brief word with Jacqui about her job caning men of his profession, assuring her that he hadn’t been one of her clients:

‘Don’t worry about legal London in the 1980s, I wasn’t here then.’

PARENTHOOD

In her witness statement, Jacqui has said that she talked to Lambert many times in detail about how much she wanted to have a baby, and how worried she was about not being able to conceive.

Bob Lambert and Belinda Harvey

She didn’t use any contraception until after TBS was born, and Lambert never suggested doing so either.

TBS was not a mistake and Jacqui was elated when she found out she was pregnant.

Jacqui now knows that Lambert told Belinda that he’d been tricked into this pregnancy by Jacqui. Belinda says he claimed Jacqui had lied and told him she was on the pill.

Belinda’s friend Simon Turmaine has given a witness statement to the Inquiry [MPS-0723092] testifying that Lambert told him the same thing.

Additionally, whistleblower spycop Peter Francis – one of the officers Lambert oversaw as a manager – also says Lambert would refer to a prior instance of an undercover officer being tricked into fatherhood.

In his witness statement to the Inquiry, Lambert denies ever saying this. However, Jacqui believes Belinda and seems angry with Lambert:

‘He said to me he would never say anything like that about me.’

She also says Lambert wasn’t unique in this abdication of responsibility:

‘It’s something men say sometimes. They will say that, you know. They just do, to excuse what – to make the girlfriend they are with, I don’t know, feel better. So even in normal life, not spycops life, that sort of happens.’

Jacqui says that Lambert appeared to share her joy at becoming pregnant.

Lambert told Jacqui he didn’t believe in marriage and that married people were conforming to a patriarchal society. This hadn’t been as part of any discussion about them, just him holding forth on his supposed views.

He’d also said that he didn’t believe in having pets, despite taking Jacqui to get a cat. And indeed, having another cat with the woman he was patriarchy-conformingly married to.

Jacqui says that she shared his view on marriage, but then reconsiders and speaks movingly of her journey and her shifts in perspective:

‘Nor did I, really, though – well, I don’t know. Perhaps I did. Perhaps I did want that security, perhaps I did really, but obviously I wanted to please him. I was pregnant with his child and therefore, yes.

You have to remember a completely different person sits here… I absolutely see things completely different. Because for a while, I would have preferred to have believed his version than Belinda’s. And I have done a complete 180 on that…

I did think “he must have loved me, there must have been something there”. Almost like he was forced into this situation that he found himself in… I was proper angry with him. Like I proper wanted to tie him to something and torture him until he told me the truth.

But that is so negative. All it does is sort of like poisons me. So I don’t feel anything like that any more. But I am really angry about this whole situation, the whole situation. Especially when an innocent child was involved.’

Although she wasn’t seeking marriage, she did want TBS to have his father’s supposed surname ‘Robinson’. She squirms as she says this. She thought she would be with them both long-term as a family.

We are shown Lambert’s 2013 statement to Operation Herne about Jacqui [MPS-0722588]. He claims he told Jacqui on learning of her pregnancy that, while he would provide support, he would not ‘be with her in any sense as a partner’.

‘News to me,’ says Jacqui, who then detailed how Lambert came with her to all her antenatal appointments.

She also recounted how he’d lovingly reassured her that he’d told CTS he wasn’t single any more because he’d made his choice, he’d been clear that he was with Jacqui and she was pregnant with his child. He acted in every way like he was a committed partner ready to be a father.

BIRTH

Just before Jacqui’s due date, Lambert suddenly announced that he had to go away to Cumbria where his father was supposedly in care. She believed him, but didn’t understand why – given that he said his dad didn’t recognise him anymore, what could be so urgent?

Also, not having given birth before, she didn’t realise how intense an experience it was and thought she’d breeze through it, so didn’t mind him leaving.

Jacqui says she got back in contact with her parents once she was pregnant with TBS, and her mum was excited at the prospect of being a grandmother. When Lambert decided to go away suddenly, he called Jacqui’s mum to come down in case she went into labour. Jacqui remembers that her parents were unimpressed about him going off like this.

Lambert had told Jacqui that he would be back on the Sunday night, so her mum left during the daytime on Sunday. She could see Jacqui wasn’t alright and wanted to stay, but Jacqui’s father pressurised her to go. Jacqui went into labour when she was alone.

She wasn’t too worried; she had her friend Sylvia nearby, who hadn’t had children but did have lots of experience of helping cats give birth to kittens, so thought she’d know what to do!

‘I have never known pain like it. I thought I was dying. Everyone told me it would be bad period pain. It’s not. I thought I was dying. I thought why didn’t anyone tell me the truth?’

She got to Sylvia’s house and the two of them went to hospital in an ambulance. Sylvia ensured there was a message left at Jacqui’s for Lambert. Somewhere in her fourteen and a half hour labour, Lambert arrived at the hospital.

He held Jacqui’s hand and was supportive through the difficult birth. He cut the umbilical cord himself:

‘He was there for it all. When you go to have a baby, you leave your dignity on the doorstep and you pick it up on the way out, don’t you? You don’t expect a man there sharing that really important part of womanhood, especially your first, and there is all that yuck all over the place.’

Jacqui lost so much blood that she was given a transfusion.

She gave birth at lunchtime on the Monday. Her parents visited that evening. Lambert stayed throughout:

‘I thought he had a child that had gone to Australia and that he thought this was his next chance at fatherhood and he was absolutely [there], yes. Shaking the hands of the obstetricians afterwards and all that, afterwards, they were saying to him “well done”.’

The Inquiry have a photo her mum took of Lambert holding TBS. Jacqui asks them not to show it. She gave it to the Guardian to use and is upset that it has since then been reused in so many media articles. In the photo, Lambert is holding TBS and looking very happy:

‘I was obviously trying to get some sleep and all the rest of it. And, you know, all the time I was like that, he was holding TBS, alright. And bonding with TBS. Because I was like out of it. He was bonding with TBS. Cuddling him. Swaddling him, doing all the things that you do.’

Later on, Lambert told her he told her he was going off to meet some London Greenpeace friends to ‘wet the baby’s head’ with a few pints, then feed their cats, and would come back the next day. He was every inch the devoted new father.

NAMING THE FATHER

It was important to Jacqui that TBS’s birth certificate listed the names of both parents – she didn’t want the father part being left blank. At first Lambert acted like this was not a problem, but when the registrar came round, he disappeared.

She found out that, as they weren’t married, she couldn’t put his name down without him being present.

They had 42 days to get TBS registered, so she tried to arrange this. Lambert agreed to meet at the registry. It was quite a mission for Jacqui:

‘I had to get ready, get baby ready, get on the bus, get all the stuff. Make sure I have the bag with the nappy change and everything in it, and all the rest of it. And I was breast feeding and in those days you didn’t just get it out anywhere’

She waited outside the office for over an hour in the cold. Lambert didn’t show up.

She was furious. Lambert gave an excuse – she can’t remember but thinks it was something about rescuing some animals so she’d empathise – and they set a new date. He did it again.

Jacqui was livid. She pushed for them to go together in his van but he made excuses.

On the 42nd day’s deadline, she went and registered TBS by herself. The people at the office told her not to worry – it could be changed later if she came back with the father:

‘And then that is when he sort of made me feel like I was the one making a big fuss over a piece of paper. He didn’t agree with all that, people registered and things like that. That wasn’t the way he lived.’

He pointed out that, as the registrar had said, he could go back any time and sort it out. But he never did.

She says he was a good father to TBS, before he left. He was hands-on and confident with the baby, readily changing nappies. She now knows it was because he already had children with his wife.

He brought thoughtful gifts, and got someone from London Greenpeace to do an extensive astrological chart for the boy.

When she became a mother, her life completely changed. She wanted the best for her baby son. She decided that, though she couldn’t have weekends free or risk arrest, she could contribute to the animal rights movement in other ways. From mid-1985 to around 1987 she helped the Animal Liberation Front Supporters Group (ALFSG).

She understood it to be raising money for rehoming liberated animals, supporting prisoners, and for direct action. On that last point Jacqui is clear she doesn’t mean hurting people but, in line with the Animal Liberation Front principles, of committing criminal damage as economic sabotage:

‘Get them where it hurts, in their pockets! They love money so much they would stoop to that level, let them! Let them pay for it!’

She’s unsure whether the work the ALFSG did was legal or illegal.

MOVE TO DAGENHAM

In the spring of 1986, when their son was about six months old, Lambert took Jacqui and her possessions to move into her nan’s house in Dagenham. Her nan had moved out, Jacqui would claim housing benefit and pay it to her dad, but not have to pay any rent of her own.

The plan was that the young family would live there together. Lambert was supposedly a poor cash-in-hand gardener. The arrangement seemed ideal.

She says the house was quite basic and unmodernised, but far better than where she’d been living. It had a garden and seemed a much more secure place to bring up their son.

Lambert gave Jacqui frequent payments. There was no set amount, there would occasionally be more if she had a particular bill to pay.

Lambert says these payments were made by cheque but Jacqui scoffs at the very notion of it:

‘He didn’t even believe in birth certificates! How about chequebooks? Chequebooks? …

It doesn’t fit in, does it, with the anarchists. But anyway, no. Absolutely I would have fallen over in shock if he had said, I have a cheque, with a bank. Because he was so against all that.’

She is certain that he gave her regular payments in cash. It’s notable that the Special

Demonstration Squad expenses were paid out to officers in cash, and this may be the source of the money.

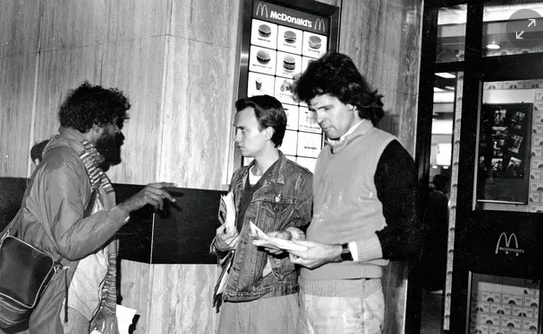

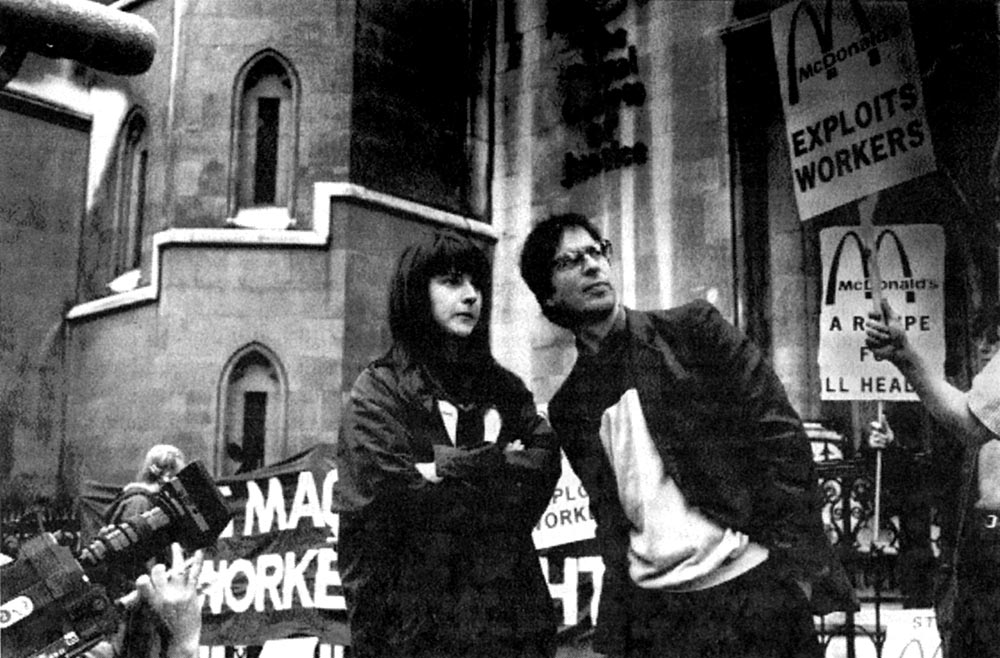

Bob Lambert (far left) with baby TBS at Hopefield animal sanctuary

She thought he was a loving, present and committed father. She trusted him to take TBS out to animal sanctuaries and other places. She trusted Lambert not to take him anywhere risky, and that the people at animal sanctuaries were compassionate and loving.

There are photos showing TBS with Lambert and other activists at Hopefield Animal Sanctuary. Jacqui describes one Lambert had taken for her of TBS on a Shetland pony.

Jacqui went away to Italy for a week with a friend, and left TBS with Lambert. She is still mystified about how this worked – he had a child for a week, he surely must have stayed away from work and his family the whole time, presumably being paid overtime.

She was increasingly bothered by his apparent immaturity and deliberately living in poverty, something she’d had no choice about growing up in:

‘I thought he needed to get a proper job. You know, I thought, God, you’re like 30 – how long is this going to go on for, you living like this? And things that I found romantic and this like Van Morrison thing, I found irritating.’

As their relationship they deteriorated, they argued more. Lambert would tend to walk away and Jacqui would feel very guilty, as it seemed like she was letting her son down by pushing his father away.

Jacqui would get annoyed by Lambert’s apparent aimlessness. They would argue and he would leave. She would go back to him, and the cycle would then repeat.

ENDING

She ended their relationship at the start of 1987, or possibly earlier:

‘It didn’t suddenly stop. There was no big row or anything like that. It was like a damp squib really.’

She was keenly aware of the difficulties and stigma faced by single mothers – they were a favourite tabloid bogeyman at the time, relentlessly portrayed as a feckless drain on society – and this is why she didn’t end it sooner.

Jacqui says Lambert seemed very distraught by it ending and yet also resigned to it. He said ‘it had happened again’, a reference to his story about having another ex-partner and child living in Australia.

Jacqui was very clear that she wanted him to stay in his child’s life, and that he was always welcome to be in contact, whatever else happened in future.

Lambert would pick TBS up from nursery or Jacqui’s parents and take care of him.

Lambert and Jacqui still had a sexual relationship after this split. He would offer to babysit TBS while she went out with friends:

‘And then, obviously, I had had a drink, there was one double bed. I would get in the bed and, well, you can make up your own – it just sort of happened. And I might regret it the next day, but that’s how it happened.’

Other times, Lambert would offer to bring round a takeaway and she understood this to mean that he would turn up with an Indian meal and a bottle of wine, then stay overnight.

LAMBERT AND BELINDA

Lambert met Belinda Harvey in April 1987 and they soon began a sexual relationship.

Jacqui assumed that he was seeing other people by this time:

‘I sort of guessed. I was as well.’

However, she didn’t know of Belinda’s existence until the truth all came out in 2012. She says she wouldn’t have been jealous of Belinda at all:

‘I wouldn’t have been angry that my son’s father was seeing another woman. I have had other children since and I have split up, and those men have gone on to make new relationships and I have always been happy – I have always tried to love my children more than I hate whatever it is with their dad.’

Beyond her personal feeling, she wouldn’t have had any jealousy about Belinda spending time with TBS, either:

‘I would have been more relieved with that than that he was with some of the activists!’

Belinda gave evidence to the Inquiry in November 2024, the same week as Jacqui.

DEBENHAMS

We move on to the subject of the Debenhams attacks. In July 1987, an Animal Liberation Front cell that Lambert was infiltrating planted three timed incendiary devices in Debenhams department stores in protest at their sale of fur. They were designed to go off late at night and cause just enough smoke to set off the sprinkler systems, and ruin stock with the water damage.

At one store, in Luton, the sprinkler system wasn’t working so the fire took hold and caused extensive damage.

Before we even start discussing it, Jacqui is weary of the topic:

‘Bloody Debenhams. Debenhams is used as an excuse for all this. Never has so much been discussed and money spent on so much to do with something that nobody was hurt.’

By this time, Lambert and Jacqui were no longer a couple but they were still co-parenting their son:

‘Looking back now I think Bob was keeping me out the way. For obvious reasons. Because things that I know about, that – he doesn’t seem to have reported on me. I mean there is no reports on me after TBS is born.’

This is true even when she was with him at events he reported on, such as a picket in the Wapping printers’ dispute. She assumes this is because if she was arrested and imprisoned like other activists there wouldn’t have been anyone to look after their son.

He occasionally brought activists to the house, mostly when she was out at work. He had always had a key.

She knew some of them – she saw Geoff Sheppard and Paul Gravett there, who are confirmed as being part of the cell. She remembers that Lambert really liked Sheppard and spent a lot of time with him, but she found this ‘bromance’ puzzling.

She thought that Sheppard and Gravett both looked up to Lambert, who appeared to ‘be the brains’ of the group.

SHE KNEW THE PLAN

Jacqui knew that Debenhams had been given a warning not to sell furs, and she knew that the plan was to set incendiary devices in the shops to set the sprinkler systems off.

Asked who she heard it from, she goes uncharacteristically quiet, and says she helped the ALF Supporters Group, and also heard things from activists back in Hackney via Lambert who was still living among the activists.

Though Jacqui approved of the Debenhams campaign, she wasn’t happy about the cell having meetings in her house. She was worried, partly because of the prison sentences being given to animal rights activists and partly because she didn’t want her son to be anywhere near where devices were being manufactured:

‘I didn’t want TBS around them, because he was a toddler, yes, and he was coming up to two. And I didn’t want him around where things like that were being made. Because he’s a toddler. He could just grab something, right. They can just grab a hot cup of tea and that is it, they are scalded for the rest of their life.

So although I was supportive, I didn’t want TBS around it. And I didn’t want Bob, the risk of Bob, and he assured me that he wouldn’t be. Although Bob was helping with the organisation and things like that, he wouldn’t do it and he says he didn’t do it.’

So if she was insisting on such assurances from Lambert, it means she knew that he was involved in making these devices?

‘I must have done.’

SUPPORTING THE ACTION

Jacqui makes it clear that she is ‘proper anti-violence’ and would never have been supportive of any action that would harm anyone. She supported the action against Debenhams because it was an attempt to stop them selling fur coats. And it worked!

Lambert told her he was significantly involved in organising the campaign but assured her that he wasn’t ‘stupid enough to get nicked’. She presumed that he would just be driving, and points out that she wasn’t aware at the time that he would still be guilty of conspiracy.

Pushed on this point by Monahan, Jacqui pushes back because Lambert has subsequently told his account to her and may have altered her memory:

‘I can’t force a memory because I now have all my “2012 memories” where obviously I have had this discussion.’

Asked why she never tried to talk Lambert out of it, Jacqui bluntly says she supported the action. Responding to whether she was impressed by Lambert, she considers her later career and elaborates:

‘I admire all the animal rights people that have done prison sentences for what they did. Because the prison sentence is completely disproportionate to the sort of sentences that I was dealing with when I was doing child protection and child abusers. Completely disproportionate. So I am impressed with them and I would try to do my best to send money to supporters’ funds and everything like that’

Asked who was in the cell, she confirms the names Lambert told her – Sheppard, Gravett, Andrew Clarke and Helen Steel, who Lambert frequently reported as being involved in things she had nothing to do with. She says she saw all of them meeting at her house except Steel.

She’s said that people didn’t usually talk about their involvement in ALF actions:

‘But I was the mother of his child and I thought I was trusted.’

She knew the three stores that would be targeted, but says she only heard about the fourth one more recently (Paul Gravett told the Inquiry that he was assigned to Debenhams in Reading but, due to train delays, had been unable to get there before closing time so dumped his devices in a canal).

Firefighter in the wreckage of Debenhams Luton store after 1987 incendiary device placed by Bob Lambert’s Animal Liberation Front cell

On the day of the attacks, Jacqui remembers that Sylvia Martin rang and told her to turn on her ‘wireless’, saying ‘it’s happened’. This implies Sylvia knew about it in advance too.

One of the stores was Jacqui’s local Debenhams, in Romford, only ten minutes away from her house. She raises the possibility that perhaps that’s why it was chosen, because it was convenient for Lambert to evaluate.

As soon as she learned that the Luton store had been seriously damaged because the sprinklers weren’t working and the fire had spread, she feared there might be serious repercussions for the activists.

She says she was ‘frantic’ and ‘desperate’ to get hold of Lambert, but couldn’t. He eventually arrived at Jacqui’s:

‘It was weird. He was sort of cool really. He wasn’t like flustered. He was sort of confident.’

Asked what Lambert specifically said to her, Jacqui responds haltingly:

‘That he, that, that – that it wasn’t him.

He just assured me that I had nothing to worry about. Nothing was going to come back to me or TBS. We weren’t in the thick of it where the police might start knocking down doors and things like that… he said it in such a way that I just assumed it was the truth.’

AFTERMATH – PREPARING TO LEAVE

Jacqui says Lambert wasn’t the same man after Debenhams. It seems he moved into the phase near the end of a spycops’ deployment where they feign a breakdown as a prelude to having a plausible reason to move away forever:

‘He was having a breakdown and I weren’t noticing it, that’s how I would have said it now. Obviously he had to make me more aware to get my attention.’

He was always telling her that he was troubled, and he’d never do anything to put her or TBS at risk. He’d suddenly look off into the distance, and when asked what was wrong, he’d talk in a very slow and stuttery way, saying his head was all over the place.

He told her about doors being kicked down in police raids. But never his own, she didn’t even know about his Graham Road address that was raided.

He still came round two or three times a week to take care of TBS. However, there was a period when he didn’t show up for a couple of weeks. She remembers her mother – usually a meek person – having a go at him for this, saying it was a very long time in the life of a toddler. But TBS was very pleased to see his dad and ran over for a cuddle.

She notes that TBS wasn’t talking yet, and that will have made things easier for Lambert:

‘I expect now in hindsight it was getting to the stage where that was going to change. TBS would like start telling me he had been to Belinda’s, or he had been there. He would start telling me things he [Lambert] didn’t want me to know.’

The Inquiry Chair, Sir John Mitting, asks Jacqui to be specific about how she knew Lambert was involved in the incendiary device campaign:

‘Because he told me.’

Mitting wants her to explain how she can be so certain:

‘That is what we would talk about, when we finished talking about TBS or whatever else was going on. I still saw it as his – obviously I didn’t know he was a police officer – but I used to see it as that was sort of his job.

It was the reason why everything that had happened in our relationship, including not being there to register our son’s birth, was because he was so committed to activism, namely anarchism and animal rights.

So therefore, it would have been – I mean, to me he seemed to have given up me and almost his son for it. So I just knew that was something he was passionate about. So I would ask him about it. Like partners ask each other about hobbies or whatever, and I was interested to know. And he knew that.’

Speaking about Lambert’s role, Jacqui once again stumbles to say it to the end:

‘He did lead me to believe that he was not – not – because he named who was. He was not – that it was going to be three shops.’

Mitting draws her back and asks her to say it in full, which she does:

‘He was not going to be the person planting the devices…

And I, you know, it’s irrelevant, but I still sort of, I still believe that. But then obviously I could have been gaslit.’

Monahan picks up this point, asking Jacqui about her discussions with Lambert since finding out the truth in 2012:

‘I can only say what he told me. And you know, we are talking about a professional liar.

Since 2012, he has promised me over and over again, and in the presence of his wife, with both of us interrogating him, right… But he’s said he’s been truthful. And that’s it. But I do know he’s a very skilful liar. Obviously, I am not that stupid…

I am no good judge of character, look what has happened to me… But things that he said and the way he said it, I believe him.’

She says Lambert has not rowed back on admitting his organisational involvement in the Debenhams attacks.

But if he didn’t plant the Harrow device, who did? There would have to be another mystery member of the cell that nobody has mentioned at all.

AFTER THE ARRESTS, ABANDONMENT

Geoff Sheppard and Andrew Clarke were arrested for the Debenhams attacks on 9 September 1987.

Jacqui recalls that, in mid-October, Lambert had taken TBS out and said he wanted to talk to Jacqui when he got back. He told her he was leaving because people were being arrested for the Debenhams campaign and it was only a matter of time before they came for him. She said that he shouldn’t worry because he hadn’t planted the devices, but he said ‘the police will fit you up’.

Lambert told Jacqui that he had lots of anarchist contacts in Spain. She got the impression it was Barcelona, though a letter later arrived from Valencia. He told her he was going on the run immediately:

‘My mindset was everyone was making a big fuss over nothing. Right. It wasn’t their fault that the store burnt down. Their sprinkler system should have been working…

I never thought for one second he would cut himself off from TBS. I never, ever thought. If he distanced himself from me a bit, it almost like at that point was sort of oh, that’s good, I wouldn’t have him bothering me. I honestly thought that he would, because that’s what he told me, he would lay low for a little while and then he would appear.’

She says this would only be an extension of what was already happening:

‘I could never get in contact with him anyway. He was always missing. He was always missing, by that time. Because he was a busy boy, wasn’t he? He had all these others. He had Belinda.’

When he last saw Jacqui, he left her a contact address:

‘He gave me an address where, if there was an emergency – and I expect he meant an emergency with TBS – that someone from there would be able to contact him and obviously if it was like a life and death emergency, I assume he would appear. But I always thought he was going to appear anyway. But, yes, he gave me this address.’

It was the Seaton Point flat, where he lived with Belinda Harvey for several more months.

Lambert’s witness statement to the Inquiry says:

‘The payment, ie the regular contributions, continued until about October 1987. In October 1987 I received a letter from ‘Jacqui’ in which she told me that she was getting married and that she and her husband-to-be wanted to bring up the child as their own. I was asked if I would consent to her husband adopting the child and I agreed. It was after this that I stopped making the monthly payment with ‘Jacqui’s’ agreement.’

Jacqui says it’s total nonsense. She didn’t even meet her future husband until February 1988.

She also describes how the adoption took a lot of time and effort because the biological father had not given permission and a huge investigation took place to try to find him.

Mitting interjects to assure her that there’s no dispute over who’s telling the truth here:

‘Plainly you know the details of your own life. Of course you do.’

IMPACT

It was devastating for her and TBS. She tried hard to find ‘Bob Robinson’ over the years. Some while later, after her husband died and TBS lost a second father figure, the boy developed a deep yearning to find his biological father.

The law firm she worked for used ex-cop private detectives in personal injury claims, and she got one of them to look for ‘Robinson’, believed to be among Barcelona anarchists.

The detective told her there was a European arrest warrant out for ‘Robinson’ which made it impossible to track him down.

Monahan pushes on this point, confirming Jacqui’s certainty, as it seems to be the first anyone’s heard of such a thing and it would have meant the police misleading the warrant’s authorities about the identity of ‘Robinson’. Perhaps they did that, or perhaps it’s just something Special Branch told the detective to keep him from looking further.

DISCOVERY

Helen Steel was one of those who’d exposed Lambert in October 2011. She tried to find Jacqui to tell her, but found no leads. Shortly after his exposure, Lambert made a public apology to London Greenpeace and a woman he had a relationship with, but not to Jacqui. He did not contact her himself.

By 2012, Jacqui had long since graduated from law school and was teaching. She was approaching her 50th birthday, her kids were more or less grown up, she saw some peace coming. Then everything was shattered again:

‘14 June 2012 at about 4 o’clock when I got home from work. As it was June, it was nice, and I saw his picture in the paper and that was him. And that’s the first I heard.