UCPI Daily Report, 29 April 2021

Tranche 1, Phase 2, Day 7

29 April 2021

Summary of evidence:

‘David Hughes’ (HN299/342, 1971-76)

Introduction of associated documents:

‘Ian Cameron’ (HN344, 1971-72)

Evidence from witnesses:

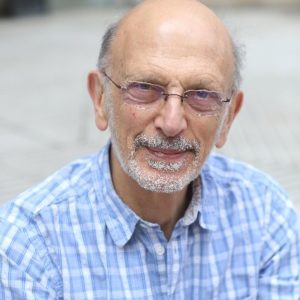

Professor Jonathan Rosenhead

Christabel Gurney OBE

Anti-Apartheid Movement demonstration, London, 15 July 1973

The Undercover Policing Inquiry read out summaries of the activities of two spycops, before hearing from two anti-apartheid activists.

‘David Hughes’ (HN299/342, 1971-76)

Summary of evidence

The morning started with a summary of evidence from the undercover ‘David Hughes’ (HN299/342, 1971-76).

He reported on the International Marxist Group (IMG) throughout his deployment, on groups linked to them, as well as Irish support organisations. Though he has provided a witness statement, he is not being called by the Inquiry to give evidence. Instead, someone from the Inquiry summarised it for us.

Hughes joined Special Branch in 1964. He had grown a beard, which lead him to being spotted by a senior officer when visiting Scotland Yard, and was called into his office for a job in early 1968. This was before the foundation of the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS). He was asked to cover the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign (VSC), who were planning demonstrations in London, and a march from Aldermaston atomic research facility.

Hughes agreed, adopting casual clothes and a fake name, and attended VSC meetings in the weekend. According to him, he submitted around six or seven reports, which were well received by management and he received a commendation.

A particular success, according to him, was learning of several activists were planning to throw stones at the Daily Mirror building due to a German sister paper having reported negatively on anti-Vietnam War demonstrations. The protest was met with a ‘substantial police presence’ and the group wondered how they knew. He felt that the success of his reporting contributed to the idea of founding the Special Demonstration Squad.

‘NO IDEA WHAT BEING UNDERCOVER INVOLVED’

Hughes returned to normal Special Branch duties not long after. In 1971, he was approached by the head of the SDS, Chief Inspector Phil Saunders – probably aware of his earlier work on the VSC – to join. Recruitment and training were fairly informal:

‘People who did undercover work either sank or swam’

He thought the unit was still feeling its way at that point. In particular, management without experience in the field did not have much of an idea what being undercover involved. He notes that when one undercover, ‘Ian Cameron’ (HN344, 1971-72), discovered that he was being investigated by his target group, the SDS office did not really know what to do – and Cameron was withdrawn shortly after.

Guidance on a variety of subjects was non-existent, but as Special Branch officers:

‘they knew, or should have known, how appropriately to conduct themselves once deployed.’

Management tried to select people ‘who could be trusted to exercise common sense and good judgment’.

‘My SDS managers were all quite “hands off” and let me conduct my deployment as as I felt more appropriate.’

TRADECRAFT

He made up the name David Hughes for himself and a cover story that he was from Glasgow and had come to London to look for work. Initially he said he was unemployed, but later got a cover job as a van driver. He had a driving licence in his cover name with the approval of management. Once he had a van (a Bedford), he kept rolls of carpet in the back in case it was ever checked.

In unusual tradecraft, he visited prominent Glasgow-based activist Tony Southall, who was involved with the Committee of 100, Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and the International Marxist Group. He was a labour movement activist in Glasgow at the time Hughes knocked on his door, introducing himself as someone interested in left wing politics who wanted to become more involved.

‘Once I went into the field in London, I told people that I was friends with Tony Southall. Tony would come down to London occasionally to attend meetings or demonstrations and I would see him at those. It was useful to have someone like that who you could speak to and be seen with. It bolstered your cover background. He had no idea I was a Special Branch officer.’

He does not recall this trip being ‘specifically authorised’ by SDS managers.

He had a number of flats during his time undercover, moving around as his target groups changed meeting locations. He would stay there occasionally, but most nights he returned to his family.

REPORTING

Hughes’ first report is on a meeting in November 1971, but he believes he had been reporting back from meetings prior to that, probably August or September. He was not tasked to infiltrate specific groups; however, sometimes he’d be asked if he could go to a particular meeting or demonstration.

In the main, he was left to his own devices and just told to attend meetings which he learned about from the ‘Agit Prop’ section of the then-radical Time Out magazine. Once at public meetings, he met others and became more involved.

As a result, he fell in with people from the International Marxist Group (IMG) and stayed with them for the duration of his deployment. They were the group most likely to have considered him as a member, of all those he reported on. Them, and perhaps the North London Claimants Union, who he was with for several years and attend conferences in London, Oxford and Birmingham.

Hughes was very active while an undercover, saying he attended between one and six meetings a week as well as weekend demonstrations. He notes that his witness pack has fewer than 200 reports attributed to him, when he would have submitted many more.

Also missing were telephone messages, where he would have called in details, something he says he would have done regularly. Among those he singled out as missing were reports on the North London Claimants Union and a Marxist class held in Streatham. After these events he often went to the pub with the groups.

He believes his reporting helped uniformed police effectively deploy numbers at protests, especially where he was able to identify splinter groups. Likewise, they helped the Security Services in their work on subversion.

NATURE OF REPORTS

Hughes reported whatever information he came across, understanding it would feed into a broader assessment of issues by Special Branch. The sort of issues he understood his bosses were interested in was

i) information on upcoming protests, or public order issues;

ii) identities of those going to meetings or protests, particularly individuals who could be be considered ‘active’ in groups;

iii) major changes within groups – people becoming more prominent or if someone was leaving, who was replacing them;

iv) who was organising things within a group, or who decided policy.

The manner in which he had reported in his previous Special Branch work was continued in his SDS reports. For instance, he reported on IMG interest in organising in factories, as he understood both Special Branch and the Security Services had a role in reporting on subversion. (Weirdly enough, this issue and the relating file [UCPI0000015678], have been mentioned in the Opening Statement of Counsel to the Inquiry as well, but the file is nowhere to be found). ‘Hughes’ notes he was not asked specifically to report on subversion, but he always did if he became aware of it.

‘Sometimes my personal views crept into my reporting. The SDS office never told me this was inappropriate or not permitted.’

He included names of new people, in case they came to prominence later. Sometimes he requested files from Special Branch, to get to know more on someone who was active. The file would then be brought to the SDS safehouse.

Hughes regularly went to the SDS flat for meetings and discussed issues with fellow undercovers – sometimes they’d end up going to the same events. Though he had no welfare issues while undercover, if he had he would have spoken to management privately when there.

At the flat, it could be quite sociable and sometimes someone would cook a meal and they’d hang around chatting – mostly about things unrelated to undercover work. Sometimes he would have a drink with another undercover.

DETAILS REPORTED

Details standing out in his reports, including a note that someone in the Spartacus League (an IMG offshoot) had been a bank robber [MPS-0732356], and that people in one meeting had been selected for a ‘special task’ during a protest which involved breaking the law [UCPI0000007940].

Hughes justified reporting on a film showing Italian activists confronting fascists by the group Fight On, because he believed the showing of such films prior to demonstrations stirred up people and meant they were more likely to become violent [UCPI0000016222].

He was asked why, at a Marxist study group [UCPI0000008823], he reports one person saying that in the event of a revolution about two million people would have to be liquidated. Hughes says that this was particularly extreme and not everyone in the class shared that view:

‘The majority of people I encountered during my deployment were not that extreme.’

One point of concern for Hughes was that the IMG had a policy of entryism into the Labour Party [UCPI0000007598], which they thought would bring them national prominence. He believed this was of interest, as it was subversive in nature. The infiltration was unsuccessful, but he added that many people involved did not engage in subversive activity.

He also reported on IMG activities in relation to the Troops Out Movement (TOM), which he says the IMG tried to take over [UCPI0000006903 – a file not yet disclosed to the Inquiry website]. This was of concern, he said, because some TOM members advocated violence – and an IMG-controlled TOM would be a threat to public order.

Hughes focused on Irish support groups as a matter of interest to Special Branch. However, he thought that much of the support offered by groups such as the IMG was limited to public statements, and that over half were opposed to lethal violence.

Among the other groups reported on were the Irish Solidarity Campaign, Palestinian Solidarity Campaign and at least one individual from People’s Democracy – over their decision to resign [UCPI0000008158]).

Hughes knew of Piers Corbyn at the time, but only in passing. He was also involved in a Marxist Study group organised by Richard Chessum (who will be a later witness at these hearings).

TRADE UNION MEMBERSHIP

Hughes joined the Transport and General Workers Union (TGWU) in his false name to bolster his cover identity. He did not become involved in union affairs but would go to big meetings to report back on speakers and discussions.

However, he would not have submitted reports as they would generally have been covered by ordinary Special Branch officers. His main interest was seeing if ‘members of extreme political groups’ were involved or trying to reach a position of prominence – an issue Special Branch were ‘very concerned about’.

OTHER ISSUES

Hughes did not witness or participate in any public disorder.

His exit strategy was to slowly stop going to meetings, saying he was going back to Glasgow.

He recalled that the then-Commission of the Metropolitan Police, Robert Mark, visited the unit:

‘It was obvious to me that he had concerns about the SDS. I remember words to the effect that “you realise that you could cause me tremendous problems under certain circumstances”.’

Full witness statement of ‘David Hughes’ (HN299/342)

‘Ian Cameron’ (HN344, 1971-72)

Introduction of associated documents

The Inquiry announced it was releasing materials relating to ‘Ian Cameron‘ (HN344, 1971-72). He infiltrated or reported on multiple Irish groups, including the Northern Minorities Defence Committee (where he was elected to the executive committee), Anti-Internment League, and London Branches of Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association and Sinn Féin.

This undercover officer lives abroad and has not provided the Inquiry with a witness statement. Some 22 intelligence reports have been attributed to him between September 1970 and June 1972. Information on him comes directly from the Counsel to the Tribunal’s opening statement (page 90).

Those before March 1972 pre-date his time with the SDS and, according to the Inquiry, he engaged in some unspecified ‘Specialist Operations’. In March 1972, Commander Rodger, head of Special Branch, had him transferred to the SDS.

All bar one report relate to Irish political groups, including the Northern Minorities Defence Force (NMDF), Anti-Internment League (AIL), and London branches of Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association and Sinn Fein, and some of the figures therein. His reporting included reporting on criminal proceedings relating to arrests at demonstrations.

From early 1972, he became focused on the Northern Minorities Defence Force, having been invited to join by the group’s chairman. Little is currently known of this group outside of Special Branch reports, who cite it as believing civil war in Northern Ireland was imminent and they were preparing to assist in this. To this end, they organised a ‘military wing’ and sought training. There is no evidence from Cameron of it engaging in violence, though members apparently had ties to the Provisional IRA.

He quickly reached a senior level within the small organisation, including being part of ‘Headquarters Staff’ and part of its National Executive Committee – where his responsibility was for security [MPS-0734416], and commanding the North West Section.

When the NMDF became affiliated with the Anti-Internment League (AIL), Cameron was selected as its delegate to the AIL. However, he was not part of the Officers Committee.

In May 1972 he was invited to travel to Derry with the NMDF, but senior management appears to have blocked this as too dangerous. After this, there is no further reporting on the group.

He also reports on AIL demonstrations, the reports [UCPI0000008651; UCPI0000007970] hyping the intended violent nature of protests, with notes such as:

‘participants will then rampage down Whitehall and the surrounding area, smashing windows’

However, the only report in which actual violence was reported was a Bristol AIL protest against a march of the Gloucester Regiment (which had been deployed to Northern Ireland), which led to AIL protestors being attacked [MPS-0728828].

There was some support within the AIL for the Provisional IRA [MPS-0728841]. His role in the AIL was sufficient that he was able to attend at least one executive meeting [UCPI0000007950].

‘David Hughes’ (HN299/342, 1971-76) recalled in his statement that Cameron ‘faced detailed inquiries by members of the groups he was infiltrating into his background’ and that he left the field shortly afterward as management did not know how to deal with the situation.

Finally, we note something not covered by the Inquiry in its summary of Cameron’s evidence. We leave you to make of it what you will, but note it was put forward when police were initially arguing Cameron’s real name should be restricted:

‘HN344 is now in his 70s and lives abroad… He has told the risk assessor that he remembers his cover name but refuses to disclose it. Nothing reliable is known about his deployment. He does not consider himself at risk of physical attack from members of his target group or groups. He advances no reason in support of the application for a restriction order in respect of his real name, beyond his understanding that his deployment would be kept confidential and his wish not to be the subject of publicity.

‘He resigned from the Metropolitan Police Service in the early 1980s. Subsequently, he was arrested for the unauthorised possession of official documents. He was not prosecuted on the advice of the Director of Public Prosecutions. Thereafter, he undertook work in the private security sector in Asia.’

Professor Jonathan Rosenhead

Professor Jonathan Rosenhead

Jonathan Rosenhead was involved in Stop the Seventy Tour, an anti-apartheid group formed in September 1969 to oppose a British tour by an all-white South African cricket team. It was just one element of isolating apartheid South Africa in an attempt to bring pressure to end apartheid.

Apartheid was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 until the early 1990s. It categorised people into a hierarchy of racial groups, with whites at the top.

The laws segregated all areas of life, reserving the best for whites. It applied to everything from education, employment and housing to which bench to sit on or beach people could visit. Most of the population was denied the right to vote. Sexual relationships and marriages between people of different racial groups were illegal.

‘Beach and sea whites only’ sign, apartheid South Africa

Rosenhead explained that they had originally targeted the South African cricket team that planned to come to Britain, but then realised there was a planned rugby team tour as well, so expanded their activities.

He said they drew on the non-violent direct action approach of 1960s anti-nuclear campaigners like the Committee of 100:

‘we had the same philosophy or actually in a sense offering ourselves up as a sacrifice to the law, to demonstrate that there were things we thought were outrageous and this was one way we could do it’.

Rosenhead confirmed that many thousands of people took part in these actions across the UK and Ireland, but he was not central to the planning of these demos. By that stage, he was more involved in ‘what we called the Special Action Group’ of anti-apartheid activists seeking to disrupt matches and sometimes invade pitches during games.

Rosenhead ruefully recalled finally reaching the pitch at a rugby match in the barracks town of Aldershot:

‘I tried several but I’m not very good at climbing fences, but I did succeed in Aldershot. The spectators there were very significantly drawn from the armed forces. So it was not just the people on the pitch who were a bit threatening, so were the spectators’

Rosenhead next explained more about the Special Action Group. He refuted the suggestion of being ‘the covert arm’ of the Stop the Seventy Tour, saying they just wanted the element of surprise. The phrasing of this question from the Inquiry seemed to suggest that there is a justification in covert surveillance if organisers have meetings in private.

The Stop The Seventy Tour campaigners felt that it was important to hold as many demonstrations as possible, at sports grounds all over the country, to show the strength of public feeling and to educate people about the apartheid regime in South Africa.

MIKE BREARLEY, ANTI-RACIST

They held a conference in London on the 7 March 1970, which was reported on [UCPI0000008660] by spycop Mike Ferguson (HN135).

One of the people who made a speech was future England cricket captain Michael Brearley, according to the report warning the delegates for the use of violence for violence sake in their demonstrations.

Once again, the Inquiry picked up on the mention of the idea of violence, as if eager to find a way to use it to discredit protesters. But Rosenhead retorted:

‘Based on that paragraph and on other documents, I think it would be unwise to take these reports as a neutral and objective statement of what was going in the meeting. I think there’s an element of self-justification here for police involvement.’

Brearley was one of the few professional cricketers to vote against playing against a whites-only South African team. It’s also likely that he is the only England cricket captain to appear in a Special Branch report.

Asked about a phrase in this report, ‘a hardcore of militants’, Rosenhead said ‘a small number of committed individuals’ would be a more accurate description. He saw it as another example of the spycops’ hyperbolic language.

In reality, Rosenhead explained:

‘Stop The Seventy Tour was a nice floppy liberal alternative organisation, which many people could join who had maybe different activities outside but agreed on this one thing.’

There was no party line and no ‘militancy’ as such, and the only thing everyone agreed on was the need to end apartheid.

There was something both incongruous as well as slightly offensive in the line of questioning pursued by the inquiry throughout this session, repeatedly pushing for any reason to imply STST activists were violent and attempting to demonise their actions.

This is especially galling given the murderous racist violence of the South African apartheid regime they were protesting against. Adding to this, that within the UK it was STST protesters who were routinely assaulted by the police, stewards and some rugby supporters, as detailed in Rosenhead’s contemporary Ernest Rodker’s statement.

SOUPED-UP

A ‘special planning group’ meeting took place at the London School of Economics on 7 May 1970. According to the report [UCPI0000008607] it was attended by Rosenhead and eight others (whose names are all redacted).

He remembers how small the room was and has serious doubts that a meeting of nine people could have fitted into it.

More seriously, Rosenhead complained about the ‘hyperbolic language’ used in the reports, and said things had been misrepresented and made to sound more serious than they were.

There was a militaristic turn of phrase to the report which says mentions how Lord’s cricket ground is ‘defended’ and how an ‘attack can be launched’ against it:

‘I think it’s been souped-up for the eyes and ears of the senior officers.’

It’s noteworthy that this report was signed-off by Mike Ferguson (HN135), whose daughter, Clare Carson, wrote a trilogy of novels around a character loosely based on her father. Perhaps she inherited her talent for creative writing from her dad.

The report goes on to list a whole range of tactics that demonstrators might use at the demo being planned for 6 June 1970.

Asked what was meant by the advice that demonstrators should ‘do their own thing once they had made it on to the pitch, Rosenhead said that in his one experience of once making it on to a pitch, he did not have anything to do except hang around and wait to be arrested. There was nothing sinister intended by this phrase, despite the insinuations of both Ferguson in 1970 and the Inquiry today.

FIREWORKS

Rosenhead noted that the report only says that things like fireworks were ‘advocated’. It means it was mentioned during a discussion, not that it actually happened. Rosenhead said that this sounded like someone who was ‘a little bit more ardent than us’.

Stop The Seventy Tour protest, Lords cricket ground, 1970 [Pic: AAM Archives]

Another SDS report [MPS-0736368] is about a meeting in May 1970 which discussed taking action at the airport when the sports teams disembarked. The violent terminology recurs, with references to a ‘commando group’ of activists who could throw fireworks.

The report also refers to the idea of smoke bombs being used at ‘some form of ‘happening’, and explicitly says that these would be ‘spectacular’. Other tactics brought up, included releasing ticker tape from a weather balloon, and jamming police radios.

The Inquiry asked if this was the plan, to cause fear among people at the airport.

Rosenhead dismissed it out of hand:

‘The whole thing is littered with wishful thinking and wild speculations’

The fact that there is no record of anything like this happening shows the fanciful nature of the report. It’s risible that the Inquiry persisted in taking it seriously.

PERSONAL SMEARS

There was a bizarre report [MPS-0736399] from June 1970 on something called the ‘Keep Politics Out Of Cricket Committee’. The report says it was a front set up by Rosenhead to gather those who opposed his political position in order to invite them to cricket matches and have a confrontation. An advert for this organisation was placed in the Daily Telegraph.

Rosenhead said it was done by someone who wanted to undermine his credibility, and he is surprised that the secret police took such a weird idea at face value.

The Inquiry Chair, Sir John Mitting, for the second time today, said this is not thought to be an SDS document, suggesting that it comes from Special Branch more widely. However, a cursory glance at the end of the report shows that is signed off by SDS officer Detective Sergeant Mike Ferguson. Another case of the Inquiry not doing its homework properly.

MISCARRIAGE OF JUSTICE AT THE STAR & GARTER HOTEL

On 12 May 1972, protesters blockaded the Star & Garter Hotel, Richmond, in order to prevent the British Lions rugby team leaving for the airport to go on a tour of apartheid South Africa. Fourteen people were arrested and thirteen convicted, including Rosenhead and SDS officer ‘Michael Scott’ (HN298, 1971-76).

The protesters were in the car park, which is on private land. However, the police lied and said they were on the public highway, and so the group was convicted of obstruction of the highway. The evidence of the undercover police officer, Mike Scott, should have been given to the defence and heard in court. A police officer should not have infiltrated the defence in a public prosecution. It all adds up to a miscarriage of justice.

Scott would have been privy to discussions between the defendants and their lawyers and would have known what the defence case would be. Rosenhead is clear:

‘All of that.. seems to be a complete miscarriage of justice and speaks very badly for the police ethics of that time or of that place’

It’s unclear how Scott knew about the protest. Rosenhead strongly refutes the story that the guy was invited to it by the mother of one of the others, Peter Hain. She had come to the UK having been politically active in South Africa and was extremely security-conscious. There is no way that she would have invited some random stranger on the phone to attend a private political meeting.

The Inquiry showed a report [MPS-0526782] dated 17 May 1972 about the arrests of Rosenhead and Rodker. Rosenhead agreed that roles were discussed and decided at a planning meeting at Rodker’s house before the action.

Rodker arranged for a skip to be delivered to the hotel car park at 4pm that day in the hope of blocking the exit:

‘I think it was rather impressive – remember we were doing all this without mobile phones’

The Inquiry persisted in trying to make the non-violent direct action look more dangerous than it was, picking up on a word in the report and asking if it was accurate to call the situation ‘a melee’.

Directly refuting that, Rosenhead said:

‘There were no fisticuffs, and there was nobody was trying to restrain us in any way.’

The report stated:

‘Rosenhead volunteered the use of three flares which he had with him… later, at the car park, he lit and threw a flare’.

Rosenhead thinks this may be a case of mistaken identity – and from his memory said that it was a ‘beautiful sunny day,’ and did not remember any smoke.

For himself, he says:

‘I have no recollection of ever owning a flare in my life.’

LEGAL PRIVILEGE BREACHED

In May, after the first court appearance, there was a meeting attended by 13 defendants, which was also reported on [MPS-0737109]. Spycop ‘Mike Scott’ was present, as were Rodker and Gurney. They agreed to meet with ‘highly-esteemed human rights lawyer’ Ben Birnberg, with a view to him representing them in this case, and to prepare some notes about what had happened.

This document, and most certainly a second one [MPS-0737108] (a report of a second meeting of the defendants held shortly before their second court appearance on 11th June) contains legally privileged information.

That a report by a police officer contains such a great deal of such information should have raised concerns to any senior police officer reading it at the time. Legal privilege is a long-standing concept in English law, this is not a new concept and would have been salient at the time.

The court case took place on 14 June 1972. ‘Mike Scott’ was found guilty and given a conditional discharge, as was Christabel Gurney. Rosenhead has no idea why his case and Ernest as well as five others were adjourned until a later date.

It appears from the documents [MPS-0526782, MPS-0737126] as if these seven pushed for their cases to be heard in a higher court, and so were postponed until that next date.

THE POLICE LIE

Rosenhead then interjected and said that his mother was a magistrate at the time of his unsafe conviction and found it difficult to believe that the police had lied about so blatantly about where Rosenhead was in the car park.

Unfortunately, Sir John Mitting appears to take the same uncritical view of police testimony. At the end of Tuesday’s hearing he thanked ‘Alex Sloan‘ (HN347, 1971) for the ‘honesty’ of his evidence.

Rosenhead ended by speaking about the way his case relates to the CHIS Bill:

‘I am concerned, in terms of the behaviour of my very own undercover officer, about the current legislation changing the legal basis for covert human intelligence sources activities. I hope that this Inquiry will perhaps retrospectively get those powers reconsidered.

‘The general picture that’s going on at the moment of reinforcing police powers is worrying given the evidence that we have in this case. And there is a continuing police culture, if you like, of the abuse of power.’

This culture seems to exist, he explained, just because the Establishment gets uncomfortable with people campaigning, instead of seeing them as people essentially performing the valuable community service of political activism.

Full witness statement of Professor Jonathan Rosenhead

Christabel Gurney OBE

Christabel Gurney OBE

In the afternoon, the Inquiry heard evidence from Christabel Gurney OBE.

Gurney was an activist in the Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM) from 1969 until 1994.

The AAM supported people in South Africa struggling against its racist apartheid system. As a British organisation, AAM focused on the ways UK companies, banks and Government supported the apartheid regime. The AAM did what they could to discourage or prevent it.

Gurney was a member of the AAM Executive Committee and the editor of its monthly newspaper, Anti-Apartheid News, from 1970 to 1980. As a result of this work she was awarded an OBE ‘for political service, particularly to human rights’ in 2014.

Membership of the AAM was open to anyone. People paid a fee and were issued with a card. The intention was to have as large a membership as possible, with broad support from those in every political party and from those in none.

Special Branch’s remit, and by extension the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS), was subversion (opposition to the UK’s parliamentary democracy), and threats to public order, However, AAM was clearly neither. In fact, Gurney pointed out, the AAM’s sole aim was to extend parliamentary democracy to southern African nations that were subject to rule by white minorities.

It is now clear that both Special Branch and the SDS spycops have always had a broader remit which extended to threats to police credibility, corporate profit, and the convenience of the government of the day.

By opposing British government policy and businesses supporting and arming the apartheid South African government, the AAM became a target despite being open, democratic and law-abiding.

MAINSTREAM METHODS

Central to the AAM’s approach was to try avoidance of doing anything which would distract the press from the real issue – the violence of the South African apartheid regime. As such it eschewed violence or heated confrontation. Rather, it concerned itself with common campaign tactics such as organising petitions, public meetings, pickets, vigils, cultural events, and mass rallies.

The AAM held many demonstrations and marches, which were agreed with the police in advance.

One example was an 8,000-strong rally in Trafalgar Square on 25 October 1970. The 10-page Special Branch report [MPS-0742860] on it records the presence of a broad range of groups including GLC Labour Party Young Socialists, India Workers Association, Catford Young Communist League, and Putney Young Liberals – all of whom are noted in the report as having their own Special Branch files.

The report shows it was an entirely peaceable affair, although the spycops – always on the lookout for the oxymoronic ‘anarchist leaders’ – say they saw:

‘small contingents of anarchists, obviously intent on “trouble” but lacking the necessary leadership’

SUBVERSIVE BISHOPS

The next report shown by the Inquiry [MPS-0742861] covered the AAM’s 1970 Annual General Meeting, held at the National Liberal Club in London.

Though 200 members were present, it was essentially private as part of its internal democracy. Yet the spycops were there. It’s astonishing that the political secret police were spying on a democratic group electing top level of officials of a decidedly establishment bent.

President was the Rt Rev Ambrose Reeves, an Anglican bishop.

Vice presidents were:

- Sir Dingle Foot QC MP

- Rt Rev Trevor Huddleston, another Anglican bishop

- Rt Hon Jeremy Thorpe MP, then-leader of the Liberal Party

- Basil Davidson, a historian who had worked for MI6 behind enemy lines in the Second World War and been awarded the Military Cross

Gurney was elected to the 30-strong National Committee at the meeting.

SOUTH AFRICAN EMBASSY

A report [MPS-0737006] on the AAM’s International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination on 21 March 1972 said:

‘the organisers are anxious that picketing should be peaceful so as to avoid adverse publicity’

Gurney agreed that this was the case with all AAM demos.

Ahmed Timol, murdered at a Johannesburg police station, October 1971

The AAM was a frequent visitor to the South African embassy in Trafalgar Square, but usually in the form of small, solemn vigils outside, such as when the regime executed anti-apartheid activists.

The Inquiry then displayed a report [UCPI0000008442] by spycops HN332 and Jill Mosdell (HN346, 1970-73) about a meeting on 8 November 1971 on a planned sit-in at the South African embassy. Fifteen people attended, one of whom was a spycop.

Gurney explained that the meeting came in the immediate aftermath of the South African police’s torture and murder of anti-apartheid activist Ahmed Timol. He had been a good friend of many South African exiles who had made their home in London, so they were extremely distressed about his death.

They wanted to do ‘something more’ than usual, explained Gurney:

‘These were exceptional circumstances.’

The report warned:

‘the sit-in would be quite militant and it would be necessary for the security guards to use force to eject the demonstrators.’

Gurney says ‘militant’ is the officer’s choice of word. She explained that they feared violence from guards and didn’t want to provoke them. They knew knew there was a real possibility of arrest.

On the day, they sat down and refused to move. Staff tipped water on them from a balcony above. The protesters passively resisted, going limp and having to be carried out.

This appears to be about as rowdy an action as the police and Inquiry can pin on Gurney or the AAM. The Inquiry, like the spycop’s report itself, paid little attention to the fact that the reason for the protests was the murder of a man thrown out of a window of a police station.

THE MET: AN EXCESSIVE FORCE

She said that the AAM knew that they, like other groups trying to bring about change in society, were likely to be the subject to police surveillance, they heard clicks on their phone lines that indicated they were being tapped, but they never imagined the other forms it took:

‘I am surprised now at the extent of it.’

The next report [MPS-0737656] was of a fundraising Christmas party at Gurney’s home on 9 December 1972. Around 40 people attended, including an undercover police officer, paying 75p for a ticket, and drinks were 12p.

Gurney was aghast that this purely social event had been attended by a spycop:

‘there was absolutely nothing subversive in any way about it.’

STOP THE SEVENTY TOUR

Gurney was involved with the Stop the Seventy Tour campaign which aimed to prevent or disrupt the planned tour by the all-white South African Springboks rugby team.

A Special Branch report [UCPI0000034318] on the AAM’s 1969 Annual General Meeting records campaigner Paul Hodges explaining to the meeting that:

‘detailed plans had already been made to harass the Springboks Rugby Tour that was due to start at Oxford on November 5. He said he appreciated that the Anti-Apartheid Movement could not be linked officially with the protestors because of the possibility of its leaders being charged with conspiracy to commit a public disorder.’

The chair is recorded as saying it was important that no publicity on the issue came from the meeting. The AAM did not ally itself with non-violent direct action, let alone organise it.

However, many individuals would have been involved with both campaign groups. Gurney said there were some tensions, but it was understood that both organisations were ultimately working towards the same aims.

Her name is listed in the report as part of the ‘core of the coming protest movement’, but she disagreed with the description. She was an activist in the campaign, but not an integral organiser. She did not attend the kind of special planning group meetings that we heard about during Jonathan Rosenhead’s evidence earlier in the day.

The AAM organised protests outside the sports grounds on the day of matches. There were demonstrations at all 24 games in the 1969/70 Springboks tour of Britain and Ireland.

The match intended to be played at Oxford was moved to Twickenham, and on the day Gurney was there trying to get on to pitch.

NOT JUST SOUTH AFRICA

The AAM also supported efforts to end white minority rule in the Portuguese colony of Mozambique, and the British colony of Rhodesia, which bordered both South Africa and Mozambique. Rhodesia had unilaterally declared itself independent under white minority rule in 1965.

United Nations Security Council Resolution 202 asked member states not to recognise Rhodesia as independent, and for the UK to work toward an equitable constitution and for the independence with majority-rule. The AAM sought to encourage this. Again, this is hardly undermining democracy or posing a risk of disorder.

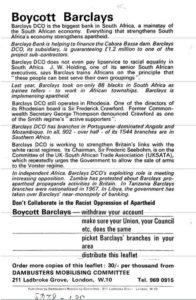

DAMBUSTERS MOBILISING COMMITTEE

Dambusters Mobilising Committee leaflet

Gurney was also asked about the Dambusters Mobilising Committee (DMC), a coalition of groups including the AAM, that opposed the construction of the vast Cabora Bassa dam project in Mozambique.

The dam was a collaboration between South Africa, Rhodesia and Mozambique’s colonial ruler Portugal. It displaced local people without compensation in order to supply electricity to apartheid South Africa, and undermined United Nations sanctions.

The DMC campaigned to dissuade British (and other European) companies from financing or otherwise becoming involved in the Cabora Bassa project.

Reports show DMC meetings were small, attended only by representatives of the organisations in the coalition. Spycop Douglas Edwards (HN326, 1968-70) is among those named, apparently as the delegate from the Action Committee Against NATO.

We’ve been told that spycops often infiltrated a relatively innocuous organisation as a stepping stone to getting into their real target. This appears to be an instance of a spycop infiltrating one organisation that isn’t a threat to public order in order to get in another that is equally unthreatening.

Gurney recounted how they spent a lot of time researching companies involved in the dam. Some campaigners bought shares so they could attend AGMs of companies, such as that of Barclay’s Bank who were guarantors of some of the dam’s financing, and pose pertinent questions to the meeting. These were very successful protests, gaining coverage in the Financial Times, etc.

One report on a December 1970 DMC meeting [UCPI 0000008114] talks of four places suggested as targets for sit-in protests, including Barclay’s Bank and ICI’s offices. The report itself says that they would expect them to be small affairs. Gurney said that she had no memory of this, and was confident she would remember if she had actually taken part in such events.

THE STAR & GARTER INCIDENT

Gurney was one of those arrested at an incident described in detail in yesterday’s evidence from one of the other arrestees, Ernest Rodker. As we heard in Jonathan Rosenhead’s evidence earlier in the day, on 12 May 1972, protesters blockaded the Star & Garter Hotel, Richmond, in order to prevent the British Lions rugby team leaving for the airport to go on a tour of apartheid South Africa. Fourteen people were arrested and convicted, including Gurney and SDS officer ‘Michael Scott’ (HN298, 1971-76).

For years, she had a vague memory of going to court for this, and being fined, and solicitor Ben Birnberg being involved. However, it wasn’t until she conducted some oral history interviews with Ernest Rodker in 2013 that she saw some press clippings with name in that she more clearly remembered being a defendant in this case.

She cannot recall the trial itself. She was convicted of obstruction (of the police and the highway), and was fined £2.

The fact that one of the defendants was a police officer – spying on the defence while working for the prosecution – is only part of the scandal. The prosecution have a duty to give the defence any relevant evidence, but clearly they were told nothing about the secret police reports which may have exonerated them. Either way, it was an unfair trial as not only was legal privilege breached by Scott’s involvement, but it should have been disclosed to the other campaigners that he was a police officer

Gurney says it is a matter of concern that we have seen no documents about whether the prosecutors or court were aware of the undercover officer’s involvement.

Mitting cut in to ask some questions. Does she remember if she was represented by Birnberg, or someone else from his firm? Does she remember if she had to pay for legal representation? Does she remember if they applied for legal aid or not? Gurney drew a blank on them all.

The Inquiry Chair, Sir John Mitting, then indicated that he will be referring the Star & Garter case to a panel with a view to overturning the convictions.

It is also worth noting that Scott was convicted under a false name as well, so lied to the court unless the magistrates were told secretly. It is unknown if he claimed legal aid in that name as well. He will be giving evidence to the Inquiry on 4th May.

ANTI-DEMOCRATIC POLICING

With the questioning over, she made some points of her own:

‘First of all I feel that it was wholly inappropriate for police officers to be spying on members of the Anti Apartheid Movement. Its only rationale was to call for democracy in South Africa, and it was not in any way a subversive organisation’

The AAM’s sole aim was to accelerate the coming of democracy in southern African nations. It was the opposite of subversive. Spying on it was a misuse of time and funds.

More to the point, those who were trying to prevent democracy were active on the streets of London and were very much a threat to public safety. She expressed disappointment that:

‘there has been no investigation into the activities of the undercover operations that were coming out of the SA Embassy.’

Bomb damage at ANC office, London, 14 March 1982. [Pic: AAM Archives]

A former head of the South African security police, General Johann Coetzee, later admitted responsibility for the ANC office bombing at an amnesty hearing of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Why weren’t the UK police investigating these incidents, rather than wasting time and money spying on the anti-apartheid campaigns?

Mitting says we don’t know why the AAM was first infiltrated because one of the spycops involved, Jill Mosdell, has now died.

WHY THE EXCLUSION?

The Inquiry noted Gurney’s concerns about the wider investigations that needed to be made, but repeated this new assertion that this Inquiry had to limit itself just to ‘the Special Demonstration Squad in its various incarnations’, which is simply not true.

The Inquiry’s Terms of Reference limit is investigations to English and Welsh police forces since 1968, but:

‘The inquiry’s investigation will include, but not be limited to, the undercover operations of the Special Demonstration Squad and the National Public Order Intelligence Unit.’

Watching Gurney give evidence today, another question on people’s lips was why did Mitting refuse her core participant status at the Inquiry? She was a leading figure in many groups the were spied on, is named in numerous spycops’ reports, and was set up for a wrongful conviction by spycops.

Being denied core particpancy prevents her from getting proper disclosure of documents or asking questions of her own, something made all the more unfair now it is clear she is the subject of a miscarriage of justice.

Full witness statement of Christabel Gurney OBE

Chrsitabel Gurney is involved in running the Anti-Apartheid Movement archives.

<<Previous UCPI Daily Report (28 Apr 2021)<<

>>Next UCPI Daily Report (30 Apr 2021)>>