UCPI Daily Report, 27 April 2021

Tranche 1, Phase 2, Day 5

27 April 2021

Evidence from police witnesses:

‘Dave Robertson’ (HN45, 1970-73)

‘Alex Sloan‘ (HN347, 1971)

The Undercover Policing Inquiry‘s current hearings (Tranche 1 Phase 2, covering the Special Demonstration Squad 1973-82) had their first day of police witnesses.

‘Dave Robertson’

(HN45, 1970-73)

‘Dave Robertson‘ (HN45, 1970-73) was questioned by Kate Wilkinson on behalf of the Inquiry.

Robertson told the Inquiry was deployed undercover by the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) in 1971, infiltrating Maoist groups.

He spied on Diane Langford who gave evidence in yesterday’s hearing. He was ‘compromised’ – ie, his true role revealed to those he spied on, as Langford described – and withdrawn in 1973.

PREPARATION

Asked why did he not steal the identity of a deceased child, he merely said ‘I just didn’t’, and that he was not aware of what other officers chose to do.

As was common with the early spycops, Robertson joined the SDS after working in Special Branch. He hadn’t done undercover work before. He was invited by serving member Detective Helen Crampton but has no idea why she approached him.

He said he didn’t know much about the unit before joining it, but:

‘Special Branch was quite a small knit community and people knew what might have been happening or not happening… everybody in Special Branch knew to some degree what was happening’

Robertson was vague about many points, even one the approximate number of officers in the SDS when he was serving. He admitted being ‘kind of aware’ of the SDS’s mission, and that it had been formed after disorder at a demonstration against the Vietnam War in March 1968.

He said the anti-war protestors ‘created mayhem’ on the day, and this was due to a lack of police intelligence. This is a familiar narrative, repeated by many of the officers who testified in the November 2020 Inquiry hearings, for instance, ‘Doug Edwards’ (HN326, 1968-71). Robertson embellished the tale, adding that he saw some demonstrators running around with scaffold poles.

According to him, Special Branch:

‘was a secret organisation anyway, and everyone in it was “positively vetted” so by definition it was a secret department.’

Pressed on how much chat there was in Special Branch about the SDS, he said ‘you wouldn’t really talk about the specifics’.

He said that he received no training as such, but does remember spending some time in the SDS ‘back office’ (recalling ‘an old police house’ at the back of a police station) before going out in the field.

This was the headquarters, where the admin was done, completely separate from the undercovers’ various ‘safe houses’.

‘Most of the people who went into that job… they just got on with the job and picked it up very quickly.’

DEPLOYED

He says he recalls Jill Mosdell (HN346) but is not sure about ‘Sandra Davies’ (HN348) – even though some reports indicate he attended meetings alongside her, and they appear to have worked so closely together that managers withdrew both women when Robertson’s cover was blown.

He says he recalls Jill Mosdell (HN346) but is not sure about ‘Sandra Davies’ (HN348) – even though some reports indicate he attended meetings alongside her, and they appear to have worked so closely together that managers withdrew both women when Robertson’s cover was blown.

Robertson confirmed that he did not type up his reports himself, he would write it up and it was taken away to be typed up by someone else in the SDS ‘back office’. He often saw these reports after they had been typed up, and knew they were routinely copied to the Security Services, aka MI5.

The first document looked at was a report [UCPI0000010254] of a Britain-Vietnam Solidarity Front (BVSF) meeting at the Union Tavern in October 1970. Long-term SDS boss Phil Saunders signed off on it.

At this point in the Inquiry hearing, proceedings came to a halt Robertson mentioned the real name of an officer whose name is restricted by the Inquiry. Those following the Inquiry’s online audio (which has a ten minute time lag precisely to prevent these sort of slips going out publicly) had no clue what was happening and assumed it was a technical glitch.

SUPPLYING INFORMATION

Attention turned to a March 1972 Special Branch report [MPS-0739241] in which MI5 had requested details about someone’s occupation. Robertson confirmed that MI5 asking for such things was ‘obviously pretty routine’.

When he joined the SDS, Robertson said he was given no idea how long his deployment would be. He says he was not in the field for three years because, as things turned out, ‘in my case, it came to an abrupt end very quickly’.

The unit’s meetings took place at its ‘safe houses’. These were described as ‘diary days’ by Robertson. Most of the SDS officers would turn up, clutching their expense claims. He sometimes went there on other days too, but there were few people around then.

He had a cover accommodation, known in the unit as a ‘duff flat’, for which he paid approximately £4 week in cash. He would usually travel to and fro after political meetings and events. He was not trained to do this; it is an example of him using his initiative. As we’d hear later on, his cover accommodation has become a point of some confusion.

He would communicate by phone (from a phone box) with the back officer, but did not have any other, personal numbers or direct lines for the SDS managers.

NO MEMORY

He was asked if his colleagues would have spoken about things like relationships and events that occurred during their time undercover? He does not remember this happening. According to Robertson ‘Special Branch officers are renowned as ‘zip-mouths’.

Mike Ferguson (HN135) was deployed to spy on anti-apartheid activists, reporting back on the Stop The Seventy Tour campaign. Asked if he ever discussed this with Ferguson, Robertson replied ‘not to my knowledge’. By this stage, it was becoming clear that Robertson is certainly very zipped-mouthed himself.

Robertson had ‘cover employment’ as well as a ‘duff flat’ – he knew someone who ran a garage so pretended to work there.

IDENTITY CRISIS

Like many of his colleagues, Robertson let his hair grow long after joining the SDS (the Squad was nicknamed ‘the Hairies’). He was not provided with any fake identity documents, and didn’t know of any other spycops being given any either. He now says that it would have been better ‘more professional’ to have these.

He remembered one occasion when a group of activists questioned him about his identity, describing it as ‘a very personal face-to-face grilling’:

‘They didn’t know who I was, and in those days it wasn’t just the police doing that, there were lots of other organisations doing the same thing… Most of the people that I met were paranoid about infiltrators’.

Asked how he convinced them of his innocence, Robertson, once again, said he couldn’t remember specifics. He clarified that they had fear of infiltration from beyond state agencies, such as rival groups; ‘everyone,’ he said.

CAR TROUBLE

Being ‘the man with a van’ was later a standard tactic of spycops, as it made them useful to the group and offered opportunities to talk to members individually.

Asked if he did anything like that Robertson didn’t remember ever doing it. He said there were no SDS cars at the time. He thinks the office may have had some hire cars but has no idea who drove them and what they were used for.

This contradicts the account of one of the people he spied on, Diane Langford, who wrote in 2015 that her group’s suspicions about Robertson were initially raised by the fact that he kept having different hire cars.

Robertson was adamant that spycops could never ever have gone out in public in a car as, if they were stopped, they would have no proper license and identity documents in their fake name. We know that one of his contemporaries, ‘Peter Fredericks‘ (HN345, 1971) did just that – and was involved in a car accident.

MAOIST STUDIES

Next, Robertson was shown his application form [UCPI0000034339] for ‘Studies in Marxism-Leninism-Mao Tsetung Thought (Spring 1971), in which he listed a number of revolutionary texts that he had supposedly read.

Given his answers up to this point, it surprised nobody that he said he does not remember much about the study group or the form.

Similarly, Robertson also cannot recall any guidance about what might constitute ‘extremism’ or ‘subversion’. He said vaguely ‘it was just part and parcel of the whole’.

‘FAIR GAME’

He confirmed that small attendance was the norm at many of these groups’ meetings. He would include everything that he thought was worth reporting – including details of flowers given to speakers. He said that ‘everything was fair game for reporting’ and it was someone else’s job to decide what to do with the intelligence he collected.

Robertson insisted:

‘I never went to anybody’s home unless I was invited’

He was shown a report he had made on the Revolutionary Marxist-Leninist League in December 1970 and asked why he thinks he was invited to attend. He said he did not know.

Robertson was asked how often he visited this home, where Diane Langford and Abhimanyu Manchanda lived. He claims that, despite Langford’s certain and vehement dismissal of the very idea, he definitely did babysit for the couple’s infant child. He said he was asked to by Manchanda and ‘couldn’t get out of it’ but never saw the baby. However, he said he could not even remember seeing the child and thinks they were in a different room from him, and that the couple was not away for an exceptionally long time.

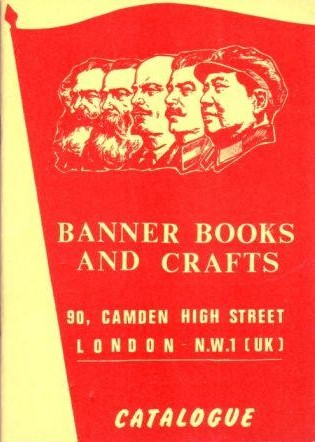

BANNER BOOKS

Banner Books catalogue

Next, a February 1972 memorandum [MPS-0730516] written by an SDS manager, Chief Inspector HN332, concerning London radical bookshop Banner Books. Robertson had infiltrated Maoist groups to such an extent that he was asked to take over running the shop when a enw branch was opened.

The memo specifies the advantages to Special Branch, including access to records and mailing lists, and being able to provide a plan of the shop and a set of keys.

Robertson played all this down, claiming that he was never alone in the shop and had no access to any records (the ostensible reason for this intrusion), and doesn’t think he ever had keys to the shop.

He has no memory of the 1975 fire at Banner bookshop (two years after his employment ended), even though someone died in it.

YOU CAN’T CALL HIM AL

Robertson claimed:

‘I never really went in and analysed things to any great depth’

But it was pointed out that he reported lots of detail about Manchanda, including some very critical comments about the man and his ‘insufferable anecdotes’.

Asked why his reports refer to Abhimanyu Manchanda as ‘Al’ or ‘Albert’ Manchanda, Robertson said that it was the name used by those around him. Langford flatly denies this – he was known as Manu. It is hard to imagine someone whose life was based on opposing to imperialism acquiescing to the practice of taking a common English name in place of their real name.

Yesterday, Diane Langford referred to a long and painful-sounding meeting in which an alleged attempted rape was brought up. She queried why, in Robertson’s report on this meeting, it was misdescribed as a ‘very personal attack on private morals’. Robertson characteristically claimed no recollection of any of this.

The report had ended with his overview ‘that the damage to the RMLL is irreparable’. He said he did not remember any of that either, despite it being a major event in the life of one of the main groups he infiltrated.

WON’T VOTE, CAN’T VOTE

Robertson did speak with certainty on one issue:

‘I didn’t vote on anything.’

Speaking for the Inquiry, Wilkinson patiently questioned him about this comment. How had he managed to never vote on anything, in such small groups? Did he really abstain from absolutely every vote? As with other officers such as Doug Edwards, a straight denial on this subject is issued without any explanation of how he managed to abstain from voting without raising suspicion.

He repeated the line about how he had never really got involved in the groups ‘because it wasn’t my place to do that’, despite his numerous highly detailed reports over a period of years.

Robertson was also questioned about parts of his witness statement.

In paragraph 53 he says:

‘I am not sure that the group posed a threat of subversion or revolution under either xxxxxx or Manchanda’s leadership given how low the membership was, but I suspect this may not have been appreciated at the time.’

Does this mean that he was not entirely convinced that these groups needed to be reported on so much? Did he feel as if he was wasting his time by spying on them? Did he ever go to his managers and suggest that he infiltrate another group instead?

‘I continued doing it until I was told to stop.’

This is inconsistent with an earlier statement that he was using his initiative.

NO PREJUDICE

Racist and sexist attitudes are common in the SDS reports of the era being examined, 1973-82. Robertson’s reports are no exception.

One of the instances was in February 1971 when he reported [MPS-0739236] that it was Manchanda that had decided he would be a stay-at-home Dad and his partner, Diane Langford, should go out to work. Robertson denied that it demonstrates sexist thinking by denying her agency in the decision-making.

Robertson had no recollection of being asked to include details of people’s race or colour in his reports. When shown examples in a report [UCPI0000021998] on a February 1971 meeting of the Communist Party of Britain (Marxist-Leninist), he justified it by saying that he had never come across ‘coloured’ trade unionists at the Post Office before. He then makes the startling observation that:

‘race was not a problem in those days…that is my personal opinion.’

EXPOSURE

Moving on to February 1973, the Inquiry asked Robertson about an incident at a meeting at the London School of Economics which ended his deployment.

His report [UCPI0000016247] appears to be the last one he made. Although it’s dated February 1973, he dates it from memory as December of that year.

According to him, he came face to face with a neighbour, Ethel, who recognised him and said ‘here’s Scotland Yard, come to take us away’.

Robertson said he had only met Ethel once and did not know her surname and cannot remember her being Irish (or otherwise).

This conflicts with the account of Diane Langford, who was sitting with Ethel, and says that she recognised him from living close to her in known police accommodation, and that she already knew him by name.

He said he did not panic but just ‘took steps to ameliorate the situation’, specifically ‘pretended to give her a hug’ and whispered in her ear to say nothing.

‘I turned around, went out, down the stairs, and walked away at high speed for about ten minutes.’

According to Langford’s statement, Robertson was significantly more violent and threatening – grabbing Ethel’s wrist and leading her out, then threatening that ‘something nasty’ would happen to her family in Ireland if she told anyone he was a police officer.

DEPARTURE

It seems that Robertson then phoned one of his bosses, then Chief Superintendent Phil Saunders, at home to report this. (He said earlier that he did not have the managers’ home numbers though). He says he was visited the next day by some very senior officers, including Vic Gilbert, Deputy Assistant Commissioner of the Met and in charge of Special Branch at the time, as well as Rollo Watts.

Robertson’s written statement has more details of this SDS deployment-ending meeting. He says that Phil Saunders was a ‘gentleman and he would have dealt with it appropriately,’ but was not present, and suggests that Gilbert and Watts were only concerned with any damage the incident would do to their own careers.

Robertson knew he could not stay in the SDS after this incident. In all of the annual SDS reports and accompanying letters to the Home Office, the dangers presented by exposure of the work of the unit are repeatedly emphasised.

Although this compromise led to his deployment ending, he says it did not harm his career in the police force. He went to work elsewhere, returning to the SDS to assist with admin in the 1980s.

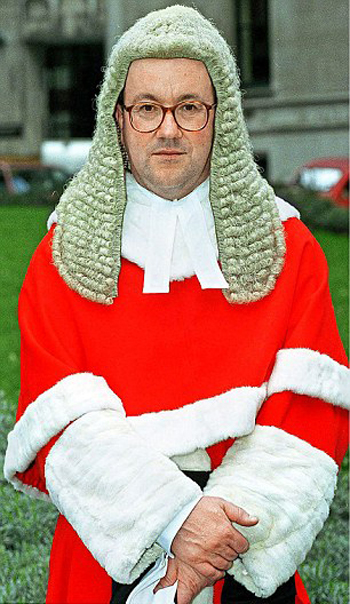

Sir John Mitting

The Inquiry’s Chair, Sir John Mitting, then appeared on-screen with a question of his own. He asked for more details about Robertson’s ‘duff’ accommodation. This appears to be in reference to inconsistency in his account of his SDS accommodation.

Robertson described it as a room in a ‘filthy’ house in West End Lane, run by a ‘large Irish lady’. He said that no, he was not aware of any other police housing nearby at that time.

Quite how this tallies with Ethel’s account is unclear. He says he never saw Ethel again, not that evening or since.

Mitting then returned to the screen to say that he has not received a copy of Diane Langford’s dissertation (which he only requested from her approximately 21 hours ago). It is unclear what this has to do with anything. This Inquiry has been running for years, has had months to avail themselves of her dissertation, or any other useful evidence.

Phillippa Kaufmann QC, representing victims of spycops, then appeared on screen. She got as far as saying that she sought some clarification from the Chair before Mitting rudely shut her down immediately, saying ‘I am not here to answer your questions’.

This is in accordance with the disrespect that he has shown Non-State Core Participants’ legal representatives on other occasions.

Written witness statement of ‘David Robertson’ HN45

‘Alex Sloan’

(HN347, 1971)

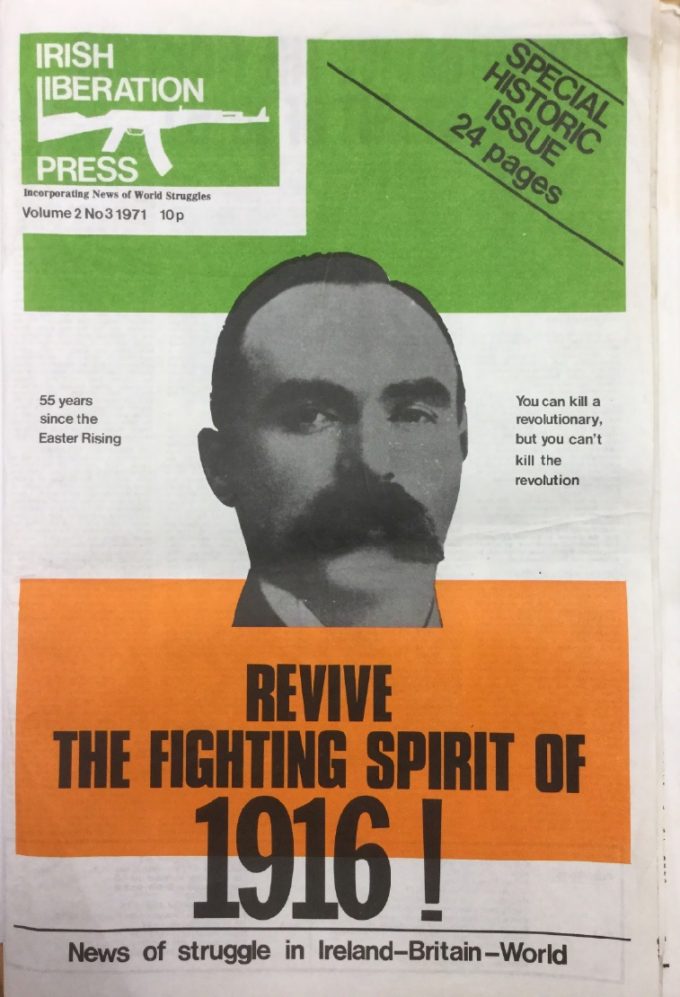

We heard from ‘Alex Sloan‘ (HN347, 1971) in the this afternoon. He infiltrated a number of groups, including the Irish National Liberation Solidarity Front (INLSF) that we heard about yesterday. He also submitted a written witness statement.

Sloan says he has no recollection of being recruited to the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) spycops unit. His witness statement says that he had no formal training. Asked how he knew what was expected of him, he asked if this was in ‘moral terms’ or otherwise.

Sloan knew, from his time in Special Branch, that they ‘would be interested in anything that was subversive to the State’. He said that those who joined the Branch were ‘probably politically aware anyway’.

Asked if he understood what was considered ‘subversive’, he came up with an answer that already starts to sound familiar:

‘It wasn’t for me to judge… I would just listen… and relay the facts to my senior officers.’

He thought Special Branch were quite intelligent, and would make well-considered decisions.

Sloan was quick to add that he never committed any criminal offences and this would have been against his nature. He conceded that some officers might have done something ‘minor’ , but never something that was ‘serious and violent’.

He then volunteered his Thought of the Day:

‘You can remember the truth easily but to remember your lies is very difficult sometimes’

This provoked some laughter in the Inquiry’s hearing room.

NO GUIDANCE, NO ADVICE

Sloan was then asked a series of questions that once again underlined how little guidance and preparation the undercovers could expect.

During his deployment he had a rent book in his fake name, but no pay slips or library card. He told everyone he worked as a mechanic, but nobody ever asked to see his driving license. In fact, he doesn’t recall using any documents to back up his cover story. The use of fake identities was something that evolved further after he left the unit.

He was never asked to write an autobiography for ‘Alex Sloan’. He was not given any guidance about what to do if his cover was blown. He was not told about ‘legal professional privilege’, which means that he should not have been present at any legal discussions between lawyers and their clients. He thought that if an undercover was offered a responsible position of a target group (like treasurer or secretary) they should accept it, but admitted that he didn’t receive any instruction on this from his managers.

He also admitted that he didn’t fully consider the risks at the time, but looking back now, he sees that this work could have been ‘pretty dangerous’.

HOUSING

Looking at a memo on the SDS’ expenditure in 1971 [MPS-0730521], Sloan’s cover accommodation – which he describes as a bedsit – cost £20 every 4 weeks.

He then described the flat where the spycops met – he remembers a large lounge but says he doesn’t remember what other rooms it had or even if it had a kitchen. Attendance at the meetings varied – 6-8 undercovers at the most – plus the two senior officers.

There is some confusion about whether the bedsit of ‘David Robertson’ (HN45, 1971-73), which is listed as costing the same amount, and thus could not have been much larger than Sloan’s room, served as an SDS safe house, but Sloan accepted that he may have been confused about this.

We learnt a little more about the spycops unit’s regular meetings. Sloan says he can’t remember writing stuff down, so may have memorised intelligence before passing it on. He can’t remember who typed the reports. He saw the weekly meetings as a social gathering, a chance for the undercovers to get together and relax.

They obviously didn’t have mobile phones, but in many cases didn’t have landlines either, so would use phone boxes.

This weekly meeting was often the main time when they could communicate directly with their managers.

Sloan confirmed that he felt able to vent about issues at these meetings, and seek advice from his colleagues. He said they were ‘very open meetings’.

Asked if these offered an opportunity to speak privately with managers, he responded:

‘If I remember rightly, you could ask to talk to them privately, take them to one side, and perhaps go in the kitchen…’

At this point it seems to have dawned on HN347 that his memory had magically returned so he ended the sentence with ‘….if it was there’.

Sloan said he was ‘not terribly socially close’ to his colleagues:

‘It may come as a surprise, but being a Scotsman, I wasn’t interested in having a drink. So yes, we just sat there and discussed things.’

They sometimes talked about upcoming demonstrations. Like HN45 told us this morning, they also talked about admin stuff and settled their expenses.

ACTIVE UNDERCOVER

He described his weekly routine. The groups he was infiltrating would often meet/ be active until late at night, so Sloan would sometime sleep at their homes, rather than at his bedsit.

He described his weekly routine. The groups he was infiltrating would often meet/ be active until late at night, so Sloan would sometime sleep at their homes, rather than at his bedsit.

The SDS’s weekly meeting was on Monday, and he has said that he usually spent Tuesday and Wednesday at home and then sold newspapers every Thursday and Friday.

Sloan provided a bit more information about this. He said that they would meet up on a Friday night, and then hawk the papers around Irish pubs and dance-halls, on Saturday nights as well, not just in London but in other cities like Birmingham and Coventry. They would travel up there in minibuses, so he spent a lot of time with other members of the group. They generally sold the paper in pairs.

The Irish National Liberation Solidarity Front (INLSF) met every Sunday afternoon, and Sloan confirmed that these meetings lasted 3-4 hours, ‘probably too long’ in his words.

Asked if he ever tried to influence the direction of the groups he spied on, he said ‘you have to be very careful what you do’ and he explained that he would have checked in with his senior managers first.

When he was in Special Branch, before joining the SDS, he would often attend political meetings at places like Speakers Corner and Red Lion Square. However this was just done in plain clothes, not using any sort of undercover identity. According to his Freudian slip, ‘you garnish a lot more information’ from being inside a group in the way that SDS officers were.

PERSONAL WELFARE

Sloan explained that his wife was ‘very, very supportive’. At the time she worked and they had no children. He understood concerns about welfare – he had colleagues who were deep undercover who may have had more difficulties with their work-life balance – however the spycops’ lifestyle suited him OK.

He was then asked about the Stephen McCarthy campaign – set up after the death of this young man in 1969 (after he’d been arrested and injured by the police). According to a March 1971 report from Sloan [MPS 739483], there were a number of demos about this.

Sloan says he doesn’t remember the name Stephen McCarthy and doesn’t remember the demos, even though relatives of Stephen were arrested at them. He also says he has no recollection of meeting these relatives. Whatever, it is clear that this is an early example of spycops reporting on a family justice campaign.

Another report [MPS739317], from May 1971, includes an update on the McCarthy case. Sloan confirmed that he wasn’t given any advice about reporting on justice cases and campaigns like this that involved complaints against the police. However, he said that he felt he had a duty to give a heads up to the uniformed police if he became aware of any potential public order issues.

Sloan said he doesn’t remember all the demonstrations he attended, but would have gone out on a demonstration if Edward – very much ‘the boss’ of the group – told them to do so. Sloan then made the astonishing assertion that Davoren would have joined the National Front if he thought they would make him leader, ‘because that’s all he was interested in’.

Asked if the INLSF cooperated with the police, Sloan said ‘well, I was there’ <#spycops ‘joke’ alert>.

He agreed that the group had ‘revolutionary aspirations’, but considered it unlikely that these would ever be realised, calling them ‘Mickey Mouse’. He said the demonstrations organised by the group were small. They ‘never had the muscle or the manpower or the will’ for disorder/ riotous behaviour.

When asked if the group would have caused any public order problems for the police if he hadn’t infiltrated them, Sloan said the group ‘would have died a death eventually’, and went on to say that the activists involved ‘were never scary at all’:

‘They never gave off the vibes that they would cause aggravation to anyone, or any person or property.’

He realised that this meant there was little justification for infiltrating them, so was quick to add that it was really important that the police kept an eye on such groups ‘just in case’.

Sloan said he didn’t know much about the INLSF’s relationship with the Black Unity and Freedom Party, or about contact with the Chinese Legation. He didn’t take part in the trip to Ireland (detailed by ‘David Robertson’ earlier in the day), and in fact didn’t even know about it until he recently received the documents as evidence from the Undercover Policing Inquiry.

He was clear that he was never part of the group’s ‘inner core’, so wouldn’t have been present at their discussions. He remembered nothing about any controversy over claims of the INLSF enjoying the support of the Provisional IRA. In his estimation, the IRA would have looked at this group and thought ‘you’re of no interest to us whatsoever’.

ACCUSED OF BEING A SPYCOP

There was an ’emergency conference’ of the INLSF at the end of June 1971. Prior to this, two members of the inner circle had been expelled, and a paper had been circulated within the group. At that emergency meeting, more members walked out.

Sloan’s recollection of that meeting is that Davoren stated that another member of the group, O’Neill, had accused Alex Sloan of ‘being a pig’.

He recalls that he was sitting in the circle when this statement was made, that he feigned anger and raised his fist, and threatened O’Neill verbally, saying something along the lines of ‘don’t you ever say that about me again’.

(He made a comment first about not wishing to incriminate himself, and Barr explained that he didn’t need to fear that, due to an ‘undertaking’ from the Attorney General. He made sure to say ‘I didn’t touch him, I just threatened him’ so it is unclear why he was worried about self-incrimination.)

He says that after the meeting, he went out for some food with some of the group. He said Davoren told him, ‘I never once thought you were a pig, Alistair… or Alex’ which sounded like Sloan making a slip of the tongue, accidentally revealing his real first name.

NO INFLUENCE, NO EXPLANATIONS

Sloan strongly refuted any suggestion that he’d ever tried to influence the politics of the group. Referring to Davoren’s headstrong character, he explained:

‘What could I do to destabilise Ed Davoren?’

He says that he didn’t even realise there was a split of some kind between O’Neill and Davoren until that June 1971 meeting.

He had no explanation as to why there was such a delay between his withdrawal (at the end of June) and the report of the emergency conference (dated 16th July), and this report being produced (in August).

Next report was from August 1971 [UCPI0000007824], submitting the complete mailing list of names and addresses of the INLSF. When asked if he was ever given praise for this, he chuckled:

‘I don’t think I ever had any praise in my police service.’

Faced with a query as to whether he ever felt that he was being asked to report on groups when it wasn’t really necessary, Sloan repeated what we expect to become a returning theme in this Inquiry. He said he just tried to provide a clear picture of the groups that he spied on through his reports, and presumed that his managers would make decisions about which groups needed to be targeted.

The evidence from ‘Alex Sloan’ ended there.

The Chair, Sir John Mitting, thanked ‘Alex’ (or ‘Alistair’) for giving evidence, adding:

‘it is fascinating to me listening to honest witnesses describing unusual events 50 years ago from slightly different points of view. It brings them to light in a way that things on paper don’t.’

It is noticeable that Mitting has never thanked any of the non-State witnesses for their honesty.

Written witness statement of ‘Alex Sloan’ HN347

EMERGENCY BREAK OUTS

Spycop Mike Ferguson, possibly

During the day, there were several ‘emergency break-outs’, with the transcript and the audio of the hearings suddenly grinding to a halt. Each time, it was entirely unclear what was the matter, for people listening at home and for us in the hearing room as well. Even the Inquiry staff present there had to wait until frantic deliberations behind the scenes had been resolved.

Any party can complain to the Chair when something allegedly breaking restriction orders is being said and broadcasted. The first time it happened was the most serious one. ‘David Robertson’ mentioned the name of HN294, the second manager of the SDS.

After a break of some 20 minutes, Mitting issued a brilliantly worded restriction order, specifying the officer by naming the other half of his leadership team; we were forbidden to mention ‘the name of the manager not being Phil Saunders’.

The second time the police hit the red button was when ‘Robertson’ was asked if he remembered fellow spycop Mike Ferguson (HN135). ‘Oh yes,’ he replied, ‘his nickname was Gimli’ – the name of a character who appears in the Hobbit and in Lord of the Rings, a dwarf with a beard so long he wore his belt over it. We‘re guessing the nickname is perhaps beard-related, rather than due to deadly prowess with an axe.

Mitting did not see a reason to keep this detail from us, or the name ‘Alistair’, so didn’t issue any more restriction orders.