The recent hearing of the Undercover Policing Inquiry was a world away from the stereotype of legal proceedings. Whilst other courtrooms seize up with the stale formality and impenetrable legalese, this session was awash with dramatic force that engulfed everyone present. And not in a good way.

The recent hearing of the Undercover Policing Inquiry was a world away from the stereotype of legal proceedings. Whilst other courtrooms seize up with the stale formality and impenetrable legalese, this session was awash with dramatic force that engulfed everyone present. And not in a good way.

The Inquiry’s Chair, Sir John Mitting, was sitting in for his second public hearing after taking over from Christopher Pitchford. Concerns victims had about the Inquiry under Mitting’s predecessor have only multiplied as the bias towards police secrecy becomes markedly worse.

NEITHER TRUTH NOR JUSTICE

Mitting said that he would not tolerate the Metropolitan Police’s former tactic of ‘Neither Confirm Nor Deny‘ (NCND) being used to withhold from the public any information about large numbers of officers.

In his first public hearing in November 2017, Mitting unequivocally stated:

‘Neither Confirm Nor Deny has no part at all to play in Special Demonstration Squad deployments’

Yet he has essentially continued the Met’s policy of NCND, rebranding it by saying that revealing any details about a spycop is ‘a potential breach of an officer’s Article 8 rights’, the human right to a private life. This has been the basis of Mitting issuing blanket anonymity to batches of undercover officers in recent months.

Effectively, Mitting is saying the rights of violators are more important than the rights of the violated. Because he regards the officers’ human rights as paramount, the public won’t be told the names of these spycops who invaded citizens’ lives and breached Article 8 rights – as well as Article 3 (freedom from torture), Article 6 (the right to a fair trial), Article 10 (freedom of expression), Article 11 (freedom of assembly and association) and Article 14 (freedom from discrimination).

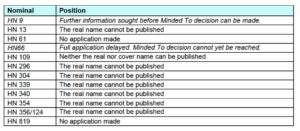

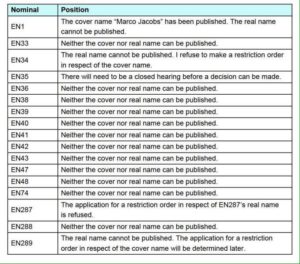

The overprotection of police privacy is now Mitting’s standard procedure. He looks at what the police officer says, and then at a risk assessment performed by another police officer, then he publishes redacted versions of these statements and issues a ‘minded-to note’ of his intentions.

Dutifully, we then go to hearings where Mitting basically goes along with what the police have recommended. He appears oblivious to the possibility that an officer might want to be anonymous because they have something to hide.

The one exception was the U-turn on Rick Gibson, whose real name is to be released, but only because the Undercover Research Group presented shocking new information about him deceiving women into relationships. Without his erstwhile comrades coming forward with the name the officer had used, the groups he infiltrated and when, this investigation would have been impossible.

NO NAMES = NO EVIDENCE = NO TRUTH

This is the fundamental issue of the Inquiry – we need to know the cover names used by officers in advance, so that those spied upon can give testimony on what the officers did. Without that, the Inquiry is reduced to the police selectively self-reporting.

The hearing earlier this month was concerned with seven officers, all of whom Mitting was intending to grant full anonymity.

Counsel for the victims, Phillippa Kaufmann QC, began bluntly:

KAUFMANN: ‘We are in no better position now than we were before the last hearing. On the contrary, we feel the situation has got worse…

‘these oral hearings, or the invitation of written submissions from us in advance, look increasingly like window dressing and look increasingly pointless in terms of actually having any realistic prospect of having any influence upon your decision-making. That is a matter of great public concern’

RUNNING INTO A BRICK WALL

Two of the officers were known by the code numbers HN23 and HN40. We are offered the bare minimum of information about them, basically just telling us that they existed. Mitting claims publishing their cover names could lead to the real names being discovered which, in turn, could lead to the risk of serious violence against the officers.

HN23 was deployed against one group and reported on other groups in the 1990s. They fear their friends and family will feel betrayed that they kept their spycop past a secret.

HN40 was deployed against two groups in the last decade of the existence of the SDS (ie 1998-2008). They were prosecuted under their false name. Despite this evidence of perjury and perverting the course of justice, the Inquiry seeks to fully protect the officer.

Kaufmann said the refusal to say anything at all amounted to Neither Confirm Nor Deny. Mitting responded:

MITTING: ‘With respect it is not a Neither Confirm Nor Deny approach. It is stronger than that. It is a flat refusal to say anything about the deployment in the open.’

Kaufmann then asked, if we can’t know about the officer can we at least be told why that decision has been taken?

MITTING: ‘I am afraid that HN23 as HN40, they are examples of deployments where you are going to meet a brick wall of silence.’

KAUFMANN: ‘It strikes us as extraordinary that we cannot even be told, for example, was this officer engaged in a deployment in relation to left wing groups or right wing groups. How on earth can the disclosure of that fact alone put that officer at risk?

Mitting was aloof and unrelenting, waiting for her to finish speaking and simply repeating himself.

MITTING: ‘I am afraid you are meeting a brick wall in these two cases and others.’

Maya Sikand, representing whistleblower SDS officer Peter Francis, spoke next about HN23.

SIKAND: ‘We come here, we hope to assist but we are not assisting because you will say, “Well, actually, no, this is a brick wall”. So it does beg the question as to why it is we are invited here’

Sikand then raised the stakes, saying that Peter Francis knows who HN23 is and the groups that were infiltrated.

She said of HN23:

SIKAND: ‘This is an officer who would have valuable evidence to give you about the nature of his deployment and what he was asked to do would be something that he needs to give evidence to you about, because it is likely that there was a level of violence authorised by Special Demonstration Squad managers in his deployments.

‘The difficulty with not disclosing his cover name is that you cannot have his evidence properly tested other than by those with whom he possibly perpetrated that violence or who were witnesses to it, in that group that he infiltrated. So that’s why we say it is of particular importance that you do disclose this cover name.’

Moving on to HN40, Sikand added:

SIKAND: ‘It is Peter Francis’s view that once more this officer would have valuable evidence to give you about the violence that was permitted by Special Demonstration Squad managers to be used by Special Demonstration Squad officers.’

At this point Peter Francis interjected in person.

PROFESSIONAL LIARS

Francis started by reminding Mitting that he and his fellow SDS officers lied professionally, that they had been trained to make whatever they say sound plausible.

Rising to his feet, Francis contrasted the dangers faced by SDS officers with those of former drugs squad officer Neil Woods who was sitting in the public gallery.

Pointing Woods out to the court, Francis expounded:

FRANCIS: ‘This man here is a former undercover officer himself, Neil Woods, the author of “Good Cop, Bad War“. He personally has led to more imprisonment of individuals totalling approximately 1,000 years for his deployment from 1993 all the way to 2007…

‘That one man has led to more imprisonment than the entire Special Demonstration Squad from 1968 to 2008. He is sitting here in his own name. I am sure he doesn’t mind saying he’s actually brought his wife along today. He walks in society freely and yet there is hundreds upon hundreds of people who would like to pay that man back…

‘I have great, huge, concerns that these professional liars are spinning you, the Inquiry and definitely these poor solicitors they are working with here.’

LAWRENCE SPYMASTER IS PRESUMED FLAWLESS

The court moved on to what Mitting conceded is ‘the problematic case of HN58’.

HN58 was the senior manager at the SDS during a crucial period in the late 1990s. It was five years after Stephen Lawrence was killed, and the Macpherson inquiry was investigating corruption and racism in the Metropolitan Police’s murder investigation. That inquiry was supposed to get to the truth and be the last word on the issue. But unbeknownst to them, the SDS was spying on the Lawrence campaign for justice, effectively trying to undermine the inquiry.

Mitting gave a clear statement in November 2017, saying that he wants this Inquiry to succeed where Macpherson and other previous processes have failed.

Peter Francis, who as an SDS officer was tasked to ‘find dirt’ with which to discredit the Lawrences and their campaign, said it is essential that HN58’s real name is released so his role can be discussed. Francis explained to the court:

FRANCIS: ‘I personally have promised Mr Lawrence, as in Stephen Lawrence’s father… that I would do absolutely everything for him because I and the Special Demonstration Squad let him down in the last Macpherson Inquiry.’

But withholding the real name is not the only issue with HN58. Like most SDS managers, he had previously been an undercover officer. We want the cover names published. With HN58, where there is evidence of wrongdoing as a manager, it suggests possible wrongdoing when he was an officer. His cover name must be published to allow the people he spied upon to come forward with their experiences.

REAL MEN DON’T LIE

But Mitting intends to withhold HN58’s real and cover names for three reasons:

1. ‘There is no known allegation of misconduct against him’.

This is absurd. How can we make any allegations against an officer if we don’t know who they are? Tell us the name and let those they spied on come forward to say if there was misconduct, otherwise Mitting is conducting his own mini-trials based solely on police evidence. Kaufmann bluntly told Mitting, ‘it is not a reason that actually makes any sense’.

2. ‘The nature of his deployment’.

This is impossible to comment on without knowing any details, but it’s clear that officers exaggerate the danger of their deployments.

3. ‘What is known of his personal and family life make it unlikely it would be necessary to investigate possible misconduct even if details of his deployment were made public’.

This is even weirder than point 1, and nobody seemed to understand what Mitting was alluding to. When challenged, he replied ‘I know more about this man than you do’.

Exactly what he meant had to be teased out of him. Eventually he said it.

MITTING: ‘We have had examples of undercover male officers who have gone through more than one long-term permanent relationship, sometimes simultaneously.

‘There are also officers who have reached a ripe old age who are still married to the same woman that they were married to as a very young man. The experience of life tells one that the latter person is less likely to have engaged in extra-marital affairs than the former.’

There were gasps of incredulity around the court. Does Mitting really believe that if a man has stayed married to one woman for a long time he will not have deceived women he spied on into sexual relationships? And that we can be so confident of this that we don’t need to check if it applies in every case?

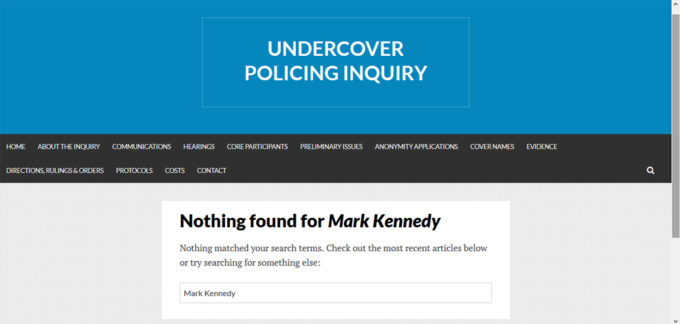

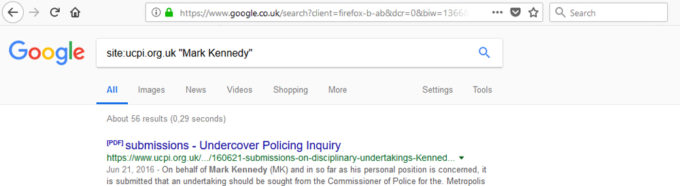

The idea that men do not hide affairs from their wives, or have arrangements where affairs are tolerated, is utterly bizarre. It is patently untrue, as we already know from other spycops. Several are known to have stayed married to the same person (at least until the truth was exposed by those they spied on), including the infamous Mark Kennedy who had relationships with four women who have now reached legal settlements with the Met.

A man possessed of opinions such as Mitting’s has no place running an Inquiry with sexual abuse of women and institutional sexism at its core.

CRIMES IGNORED

This moment also made clear that Mitting had been using ‘misconduct’ exclusively as a euphemism for ‘deceiving women into sexual relationships’. He had already made the women a special case at the November hearing, saying they deserved full answers, but not mentioning any other groups of victims.

It’s important to remember that sexual abuse was only one element of the spycops’ criminal misconduct. Assault, identity theft, incitement, burglary, perjury and perverting the course of justice were all commonplace. Mark Ellison QC found that not only did spycops lie to courts and spy on lawyer-client meetings, they also withheld evidence that could have exonerated accused people.

Officers have admitted to the Inquiry that they were arrested and prosecuted whilst undercover, yet Mitting has apparently decided this is not misconduct worthy of consideration, let alone telling the victims about.

As Alison, who was deceived into a five year relationship by SDS officer Mark Jenner, wrote in the Guardian last week:

‘Rather than one senior judge, this inquiry requires an independent panel of experts, along the lines of the one that advised Sir William Macpherson in the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry, or the Hillsborough Independent Panel.’

WHAT’S THE POINT?

Helen Steel was deceived into a two year relationship by undercover police officer John Dines. He was only exposed through her diligent research.

Having represented herself in the same courts for the McLibel trial, the longest trial in English history, Steel is now representing herself at the Undercover Policing Inquiry, but in effect she spoke for many:

STEEL: ‘Frankly the way that the Inquiry is currently conducting this process gives the core participants absolutely no faith that it is interested in learning the truth because it is basically believing everything the police says and saying, “I don’t need to hear you because you haven’t got anything you can tell us”…

‘it is just a pointless waste of money if we are not being told enough information to effectively participate this Inquiry. It is not going to get to the truth and the whole purpose of this Inquiry is to stop the human rights abuses that were being committed by these units. You can’t do that without our participation and it is a joke that we are being excluded from this process. It is an insulting joke.’

The victims should be heard. They – the people who brought the issue into the light – are the most keen to have the truth publicly established, but they are repeatedly running into Mitting’s brick wall. His excessive faith in police integrity, and refusal to be substantially swayed from that trust, is steering the Inquiry far from its goal.

Last week the Inquiry announced that, despite all that was said at the hearing, it will withhold the real and cover names as intended (with the exception of probably releasing the real name of the now-deceased Rick Gibson). In other words, if an officer is still married to the person they were with at the time of deployment then they are assumed to be blameless and will be protected from scrutiny.

The Inquiry cannot fulfil its purpose like this. Something fundamental must change if there is to be any point in it at all.

Last Wednesday, 21 March 2018, Jenny Jones (aka Baroness Jones of Moulsecoomb) probed the government about Britain’s political secret police in the House of Lords.

Last Wednesday, 21 March 2018, Jenny Jones (aka Baroness Jones of Moulsecoomb) probed the government about Britain’s political secret police in the House of Lords.

The recent

The recent  There are two new names on the list of known officers from Britain’s political secret police; Christine Green and Bob Stubbs.

There are two new names on the list of known officers from Britain’s political secret police; Christine Green and Bob Stubbs. This week sees another preliminary hearing of the public inquiry into Britain’s undercover policing scandal.

This week sees another preliminary hearing of the public inquiry into Britain’s undercover policing scandal.