UCPI – Daily Report: 25 November 2024 – Geoff Sheppard

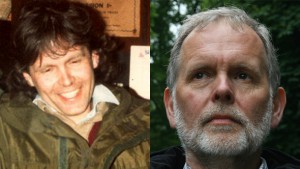

Geoff Sheppard (left) and Paul Gravett in the 1980s

At the Undercover Policing Inquiry, Monday 25 November was devoted to animal rights Geoff Sheppard completing his evidence, which he did remotely.

For yet another week, there was no livestreaming of Inquiry hearings, and once again the public relied entirely on live tweeting from Tom Fowler and ourselves.

RECAP

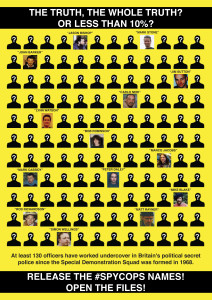

This summary covers Monday of the fifth week of ‘Tranche 2 Phase 2’, the new round of hearings of the Undercover Policing Inquiry (UCPI). This Phase mainly concentrates on examining the animal rights-focused activities of the Metropolitan Police’s secret political unit, the Special Demonstration Squad, from 1983-92.

The UCPI is an independent, judge-led inquiry into undercover policing in England and Wales. Its main focus is the activity of two units who deployed long-term undercover officers into a variety of political groups; the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS, 1968-2008) and the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU, 1999-2011). Spycops from these units lived as activists for years at a time, spying on more than 1,000 groups.

This was the third day of Geoff Sheppard’s evidence – for his earlier evidence, see our report from the previous hearing.

Having already covered his involvement with HN10 Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’, this hearing was intended to focus on the other spycops who targeted him.

Click here for the day’s video, transcripts and written evidence

BACKGROUND

Spycop HN1 ‘Matt Rayner’ while undercover, February 1994

In 1995, Sheppard was set up by spycop HN1 ‘Matt Rayner’ and received a seven year sentence. Rayner’s boss at the Special Demonstration Squad was Bob Lambert who, in his earlier career undercover in the 1980s, had ensured Sheppard got a four year prison sentence.

‘Matt Rayner’ hasn’t had the same level of attention as some other spycops, but he is one of the central figures in the infiltration of animal rights campaigning in the 1990s.

He stole the identity of a dead child, had a long-term relationship with activist Denise Fuller, broke the law many times and was convicted under his false identity, and set Geoff Sheppard up with a wrongful conviction.

Sheppard got into animal rights activism in 1980 when he watched a documentary on factory farming and became a vegan, though he didn’t know the term at the time.

He went on his first demo in 1981 and got involved in direct action in 1984, giving the example of breaking windows of butchers’ shops or burger chains.

Asked if he was ever involved in liberating animals, he said:

‘No, actually that’s one of my regrets, that I was never involved in actually liberating an actual animal. But I could give you an idea as to why that was the case.’

As to whether his animal rights activism ever caused harm to anyone, Sheppard replied:

‘Not physically, no. But possibly to their bank balance… that was a deliberate decision… I wouldn’t have felt comfortable harming anybody.’

He said that he’d only been hunt sabbing on two or three occasions when extra help was required because of potential violence from the hunters. He had become involved in London Greenpeace in part because of its support for animal rights.

DIFFERENT GROUPS, COMMON PURPOSE

The Inquiry showed a secret police report by Lambert (UCPI028517) which said that there was close cooperation between the Animal Liberation Front and London Greenpeace because:

‘The latter is dominated by anarchist Animal Liberation Front activists or supporters, who see the name ‘London Greenpeace’ as a good vehicle for promoting Animal Liberation Front propaganda and actions.’

Sheppard, echoing numerous other witnesses before him, said that simply wasn’t true, and indeed many people in London Greenpeace had no interest in animal rights.

‘I used to attend London Greenpeace quite often and I certainly wasn’t thinking of it as affording me a cloak of respectability, not at all…

I think people attended London Greenpeace such as myself who were interested in animal rights and animal liberation, it was because there were some people there who were interested in those issues.’

It’s one of the major recurring misconceptions we’ve seen in police reports throughout the Inquiry. They imagine activists are looking for ways to hoodwink others into supporting their cause. They seem incapable of believing that people genuinely support the causes and act with integrity. This says much more about those writing the reports than it does about their subjects.

The Inquiry referred to Hackney and Islington Animal Rights Campaign, which Sheppard was involved with in the 1980s and 1990s. He confirmed their meetings were open to the public and held monthly.

‘it was a group that would hold public meetings. It would mainly be at the weekend or on a Saturday going out on the streets handing out leaflets about different aspects of animal abuse. That was the kind of thing that they would do.’

He was shown a range of reports about the group that named him (UCPI02848, 3 January 1986 by Lambert; MPS-074410, 17 March 1992 by HN2 Andy Coles; MPS-074410, 10 April 1992, also by Coles; MPS-0740030, 15 March 1993 by Rayner; MPS-0744116, 12 November 1993, also by Rayner). The last of these said the group was disbanding.

Sheppard disputed the description of him as having a prominent role:

‘Well, I wouldn’t say I was one of the principal organisers. I definitely used to help out to some extent. I seem to remember that for a time I was the person who would go and open up the room if there was a public meeting… I helped in that respect, certainly.’

This is another inaccurate recurring theme of the police reports. The police seem to find it difficult to conceive of loosely affiliated like-minded people acting in concert, and so they try to superimpose a hierarchy on to any groups spied on. They pick members and attribute commanding roles to them. This also helps in making their reports sound like they’ve uncovered secrets.

Additionally, as we’ve especially seen in many of Lambert’s reports, the officers will organise things themselves but attribute it to group members.

IMAGINARY HIERARCHY

Sheppard was then shown a report (MPS-0744109, 20 July 1992, by Matt Rayner and Andy Coles):

‘Geoff Sheppard, the life and soul of the Hackney and Islington Animal Rights Campaign has decided that for the time being the group will confine itself to an educational workshop with public meetings, enlisting the support of guest speakers and videos.’

This makes him not only the central figure but able to unilaterally take decisions on what the group will do. This is not what he was, nor how the group worked.

‘I think these undercover officers tend to exaggerate everything that they say… my nature is not really the life and soul of anything, to be honest.’

The Inquiry turned to the Animal Liberation Front Supporters’ Group (ALFSG), which Sheppard had supported since the mid-1980s and was briefly active in running its finances in the early 1990s. He described the ALFSG as supporting animal rights prisoners, and producing a newsletter.

A 1993 report by Rayner (MPS-0744489) said Sheppard left his role in order to commit himself to more direct animal rights work such as street protests:

‘Sheppard remains convinced that the only really effective way to fight vivisection is through economic sabotage’

This is quite a sensationalist way to describe activities, and also inaccurate, as Sheppard pointed out:

‘I don’t think that was quite right. I would say economic sabotage was certainly one of the ways to fight vivisection, but there were also other good ways to fight vivisection as well, you know, through showing people the reality of vivisection on the streets, with leafleting, back in those days, anyway.’

A 1992 report by Andy Coles (MPS-074225) revealed the supposed command structure of the ALFSG:

‘The central organising figure behind the Animal Liberation Front Supporters Group is Vivien Smith who, despite her incarceration in Holloway Prison, is still able to carry out this role. Smith is assisted by Geoff Sheppard, a regular visitor, who acts as her agent.’

Sheppard rebuffed the whole thing.

‘No, that’s an exaggeration. I remember visiting her in Holloway Prison on one occasion. Just once. So, you know, “regular visiting” is a ridiculous thing to say. It just simply wasn’t true… I certainly have no recollection of acting as her agent, no.’

LONDON BOOTS ACTION GROUP

They then turned to the formation of London Boots Action Group, another campaign against vivisection. At that time, retail chemist Boots had two of its own vivisection facilities. The Inquiry showed reports from HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’, as well as ones from Andy Coles that mentioned Sheppard.

‘we would stand outside Boots stores, not obstructing the entry or anything like that, but we would be handing out leaflets to people as we were standing outside various Boots stores in and around London. Certainly from my point of view, that’s the main activity that I remember. You know, rather boring hours of activity getting probably quite cold standing outside Boots stores.’

A Matt Rayner report from 1992 (MPS-073939) said:

‘11 members of the London Boots Action Group travelled to Margate to join the national demonstration against Charles River, the parent company of Shamrock Farm near Brighton [breeders of monkeys for vivisection].’

It described a peaceful demonstration and then:

‘In bad temper and some frustration, the London Boots Action Group contingent went into Margate to vent their anger on local branches of Boots and McDonald’s. [privacy] and [privacy] let off a handful of stink bombs in both establishments, while [privacy] and [privacy] entered Boots, loaded baskets with goods which they packed very slowly at the checkout before casually leaving the store without the goods and without paying for them.

‘[Privacy] and [privacy], with [privacy], [privacy] and [privacy] repeated the performance in McDonald’s by ordering huge quantities of food and drink, which they abandoned when produced. These actions cause intense annoyance to the staff and management at both places’

Spycop HN1 ‘Matt Rayner’ leafleting at an anti-vivisection protest outside a branch of Boot’s

Sheppard confirmed he was at the earlier demo but has no recollection at all of the later events, and said he never did anything like that.

It’s worth mentioning that even if it all happened exactly as described, annoying retail staff is hardly a matter for an elaborate undercover operation with copies of reports being sent to MI5.

Another Rayner report (MPS-074579) said someone at a London Boots Action Group meeting had suggested a protest outside the home of a director of Boots. Sheppard has a vague memory of doing such a protest once which, he pointed out, was legal and quite common at the time.

Several reports described security concerns in the group and that some members, including Sheppard, dismissed them because the group had no secrets. It was open to the public and produced a newsletter about its activities. They said that if anyone wanted to discuss sensitive or illegal matters they shouldn’t do so at the meetings.

Asked to elaborate on the clear implication of this, Sheppard said:

‘London Boots Action Group, in its own right, was not involved in anything like that, but obviously individuals who attended London Boots Action Group may have been, such as myself, involved in direct action.’

HIDDEN TREASURER

Moving on to 1995 and London Animal Action, a Matt Rayner report (MPS-0741078) said the group held two bank accounts. One had Paul Gravett and Sheppard named as signatories, the other had Gravett and Rayner himself.

Though it’s alarming to think of spycops taking on such a pivotal active position in a group, by 1995 it had become standard tradecraft.

As an illustration of how common this was, we had previously learned about these officers’ roles in a single week of Inquiry hearings:

HN354 Vincent Clark ‘Vince Miller’ (1976-79)

Treasurer, SWP Walthamstow branch

Treasurer, SWP Outer East London District

HN80 ‘Colin Clark’ (1977-82)

Treasurer, SWP Seven Sisters & Haringey branch

Treasurer, SWP Lea Valley District

National Treasurer, Right to Work Campaign

HN356/124 ‘Bill Biggs’ (1977-82)

Treasurer, SWP Plumstead branch

HN155 ‘Phil Cooper’ (1979-83)

Treasurer, Waltham Forest Anti-Nuclear Campaign

National Treasurer, Right to Work Campaign

SPYCOPS PASSING OFF THEIR WORK AS HIS

We were then shown reports detailing the formation and function of the Animal Liberation Investigation Unit. It was described as co-ordinating regional groups to support and attend one another’s activities which were specifically described as within the bounds of the law.

Those setting it up had to be personally informed and vouched for. Sheppard said he has no memory of being invited and doesn’t believe it happened. Despite this, the reports named him as the London co-ordinator, and we were treated to an extensive description of the responsibilities that entailed.

Sheppard apologetically responded:

‘I was not in any way involved in the Animal Liberation Investigation Unit. Not as far as I remember, anyway. I am pretty sure that I was not. So that seems to be fabricated, really.’

Asked why Rayner would have said this, Sheppard said:

‘I would like to know whether he was possibly acting in that role, and maybe he was putting my name there instead.’

We next looked at a Special Branch report from outside the Special Demonstration Squad (MPS-073960), concerning Operation Wheelbrace which targeted animal rights activists:

‘Geoff Sheppard has become very much a force unto to himself and is not part of any specific group dealt with under Wheelbrace. He is behind the new British Anti-Vivisection Association.’

Sheppard was categorical in his response:

‘I was certainly not behind it, I had no involvement in setting it up… I wasn’t really involved, other than buying packs of leaflets off them in order to distribute. Possibly I used to go round door to door putting them through letterboxes. That was my involvement, really, with that organisation.’

Asked about all these groups being spied on, he declared:

‘it was totally unnecessary for the undercover police to be doing this. I mean, these groups had no intention of toppling British democracy, they weren’t involved in violence against individuals, and, as I said before, as far as I am aware there were a lot of police informers in the animal rights movement, apparently, so I don’t see why there was any necessity to have undercover police officers involved.’

THE OFFICERS

Having looked at the various campaign groups, the Inquiry moved on to ask Sheppard about the spycops themselves.

They started with HN11 Michael Chitty ‘Mike Blake’. Sheppard has a vague recollection of meeting him once, when Chitty drove a carload of people back to London after attending a trial in Sheffield.

In 2014, Chitty told Operation Herne – the Met’s self-investigation into spycops before the public inquiry was announced – that he’d known Sheppard well. Sheppard himself denied this.

JOHN DINES & WRONGFUL ARREST

Moving on to John Dines, Sheppard remembered him from London Greenpeace, but without much in the way of specifics.

They never socialised together and:

‘The only main thing with this individual was that he threw a bag of flour at an anti-hunt demonstration and I got arrested for it.’

The Inquiry went into this in some detail. It was a Horse and Hounds ball, held at the Grosvenor House Hotel in 1991.

Sheppard described his presence:

‘this was a hunt ball, so these were people attending the ball who were engaged in the practice of hunting wild animals to death and our presence there was to let them know that we very much disagreed with that so-called sport…

‘there were quite a few people there. So possibly 30 or 40 people, perhaps… it could have been 60 people, maybe… as far as I remember, it was just mainly shouting. Holding placards, that kind of thing.

‘I don’t have a memory of seeing the bag of flour being thrown or landing. I probably saw it but I just can’t remember it. All I can remember is my arrest… maybe John Dines was standing behind me, but I never saw who threw it.’

Sheppard was arrested. He was later told that Dines was the one who’d thrown it. Sheppard was tried and convicted.

‘afterwards, outside, John Dines must have come outside with me and I think one of the officers who had been involved in the arrest was coming out and John Dines shouted at him, “Tell the truth in future”. That’s the bit that I remember.’

This makes it a miscarriage of justice – a police officer had evidence that exonerated the accused, but withheld it from the court. This is far from the only time spycops did this. Mark Ellison KC’s 2015 report on spycops and miscarriages of justice says there was evidence of this happening numerous times.

Spycop HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’ while undercover

The case that brought the whole spycops scandal to the public eye, the exposure of Mark Kennedy, became common knowledge when prosecuted climate activists asked to see his reports. Rather than hand them over, the state withdrew and in January 2011 the trial collapsed.

It later came out that Kennedy had recorded conversations that exonerated the accused. Had he not been unmasked between the arrests and the trial, there would likely have been wrongful convictions.

Plainly, police withheld evidence in cases that resulted in Geoff Sheppard’s more serious convictions too.

Somewhat bizarrely, the Inquiry asked Sheppard at some length about why he didn’t complain to police about his wrongful prosecution.

John Dines had deceived deceived Helen Steel into an intimate relationship. Sheppard confirmed that he knew Steel from London Greenpeace meetings but he didn’t socialise with her or Dines:

‘I was always rather a standoffish type of person. I didn’t go to a lot of social events, so probably I didn’t have as many opportunities to see them together as other people would have had.’

ANDY COLES

Andy Coles was the next officer discussed. He infiltrated peace and animal rights groups from 1991 to 1995. In that time, he groomed a vulnerable teenager, ‘Jessica’, into a relationship.

‘I knew him very little, but I think he was – people called him Andy Van, because he always had a van available to drive people around or move items around.’

Beyond that, Sheppard’s recollections about Coles were scant. He believes they would have been in London Boots Action Group together.

‘I don’t actually remember him being with me on pickets outside Boots, but he probably was doing that… If you ask me to picture inside my mind right now a meeting of the London Boots Action Group with him sitting there, I don’t think – I can’t really picture him…

‘You know, if you are going to talk about Rayner, then I have much more knowledge, because I was closer to him. I wasn’t very close to this Andrew Coles, he had obviously not been assigned to focus on me, because he didn’t focus on me and I had very little involvement with him.’

One of Coles’ reports from 1992 describes a woman involved in London Greenpeace, London Boots Action Group, and other groups in South London. It says she does not approve of ‘lethal force against animal abusers’ and claims this means she disagrees with ‘her boyfriend, Geoff Sheppard’.

Sheppard rejects this outright.

In an undated document called ‘Six months post-op debrief’ (MPS-0743479), presumably six months after Coles’ deployment ended in 1995, he said he was a close associate of Sheppard’s in the ALF, and that he’d gained the trust and confidence of extremely good security-conscious activists, including Sheppard.

‘Well, that’s just completely incorrect, because he was not… he definitely never gained my trust or confidence. I had very little to do with him…

I had a prison sentence already for the Debenhams act, so maybe it boosted his credibility to make out that he was closer to me than he actually was.’

MATT RAYNER

In contrast, Sheppard remembered HN1 ‘Matt Rayner’ well.

‘I don’t even know if you would say we were friends, but I think we developed a situation where we were close associates… And the reason I don’t use the word “friend”, is because I don’t really remember socialising with him all that much, or if at all.’

Speaking to Operation Herne’s investigation into spycops, Rayner described himself and Sheppard as ‘firm friends’.

‘I think that’s a bit too strong. As I said, he was a close associate and that association was all based around animal liberation, based around those issues. I wouldn’t say that we would become firm friends, I think that’s putting it too strongly…

‘I trusted him because he showed a willingness – a great willingness – to be involved in direct action and I was involved with him in direct action on quite a few occasions.’

A police document (MPS-074616) authored by spycops manager HN67 ‘Alan Bond’ in August 1992, not long into Rayner’s deployment, was quoted:

‘Had an informal chat with HN1 [‘Rayner’] – things within his organisation are obviously settling down and he now appears to be progressing steadily.

‘Geoff Sheppard has now taken HN1 under his wing and is telling other comrades that he can vouch for him – almost as if he is acting as HN1’s mentor within the organisation.’

Sheppard called it out as false:

‘I don’t think I started doing direct action with him until some time in 1993. So at that time I wouldn’t have had any idea whether he seemed to be a trusted person or not.’

Sheppard said Rayner visited his home a couple of times.

The first of these he believes was around May 1994, and Rayner was with a woman he had deceived into a relationship, Liz Fuller.

The second was around March 1995, a few weeks before Sheppard was arrested, precipitating his second spell of imprisonment.

‘the thing that has stuck in my mind from that visit is that we were basically we were talking about vivisection, animal experimentation, and the kind of people that were involved in animal experimentation, and we were obviously, you know, very unhappy about these kind of people.

‘And I remember him suddenly dropping into the conversation, “well, if you would like – if you want to shoot the vivisector, then I would be willing to drive you there”. Of course at this time I had already informed him that I was in possession of the shotgun. This was the suggestion that he made to me.

‘My answer to him, because I felt that I was sort of letting him down, because it seemed as if it was something that he wanted to do. I didn’t actually say no. I said to him, “I’ll think about it”, which was my way of kind of gently letting him down. Because I thought – to me it seemed as if I was kind of letting him down by not doing something that he seemed to be interested in doing.’

SPYCOP FACILITATING CRIME

Sheppard remembered Rayner always had a vehicle – at first a van, later a car – that was used to give lifts to activists. This was standard practice for spycops – in a community without much disposable income, and events to go to that were often some distance away, being able to give lifts meant you got told about everything.

SDS officer John Dines whilst undercover as John Barker

Spycops would also use the long drives to get personal information, and drop people at home thus finding out their addresses.

Sheppard said he was with Rayner on many occasions when Rayner was the driver for people committing criminal damage to buildings connected to vivisection. This was after Sheppard’s prison term for the Debenhams actions, and also after a period of several years following his release when he was not involved in criminal activity. He remembers Rayner advocating direct action and responding in agreement.

At this point the hearing took a break for lunch. Despite their earlier promises to publish transcripts of hearings by lunchtime the next day, they have failed to do so on numerous occasions.

At the time of writing, the afternoon transcript is still not online and the Inquiry has not responded to emails asking when we can expect it. This means that we don’t have any extended verbatim quotes for the afternoon session and must work instead from notes and live tweets.

Rayner told Operation Herne that he once appeared in court as a witness after Sheppard had been arrested at an anti-fur protest outside Harrods. Sheppard himself doesn’t even remember the arrest, saying it happened to him so many times they all blur into one.

Sheppard does remember Rayner and his partner Liz Fuller and was well aware they were a couple.

John Dines reported in July 1990 that Sheppard was reluctant to get involved in taking ‘extreme direct action’ following his release from prison that March.

BACK TO ACTION

A 1993 report by Rayner said Sheppard had resumed ‘ALF-style activity’. Sheppard agrees that this is true and says Rayner was ‘putting me in the position he was in’. He explained his resumption as being half due to a residual belief in direct action, and half due to the influence of Rayner:

‘I valued his perception of me… I suppose maybe some part of me wanted to do it to please him’

The report said Sheppard had ‘gathered around him a small group of established, trusted and highly committed activists’.

He says he hadn’t, but that maybe Rayner had done this, and persuaded them all to get involved.

There were 10 to 15 actions, all of them criminal damage (eg breaking windows and throwing paint), all at vivisection institutions. There was no targeting of individuals or homes.

A report dated November 1994 talks about Sheppard developing a new ‘enthusiasm for anti-government public order type confrontation’ and going along to an anti-Criminal Justice Bill protest in October.

These were huge, broad-based protests against planned draconian new laws that criminalised protests and curtailed human rights. The protests had support from most parties except the Conservatives. It was far from ‘anti-government’.

He remembers being in Hyde Park when trouble broke out, and being charged by mounted police officers, one of whom hit him in the head with a baton. He did not break any shop windows that day (as claimed in the report).

INCENDIARY ALLEGATIONS

Sheppard freely admits four of them – including Rayner – were considering an incendiary campaign targeting Boots, but explains he got scared, and only got 95% of the way to producing an effective device. According to an expert who examined the items found at Sheppard’s home in 1995, there were components that could be used to manufacture a timed incendiary device, along with an instruction booklet.

The real Matthew Rayner in his father’s arms. He died of leukaemia aged four, and spycop HN1 stole his identity

Rayner asked to take away the 95% completed incendiary device that Sheppard had built but couldn’t get any further with. Sheppard agreed. Rayner didn’t take the booklet that detailed how to make these devices, and he assumed Rayner had his own copy.

In his witness statement, Sheppard writes of trying to make a working incendiary device, and deciding to turn it into a ‘dummy’, that would look like an incendiary device but not work as one.

Asked about an incendiary device that was recovered from a branch of Boots in Enfield, Sheppard says that was an action of Rayner’s after Sheppard said he didn’t want to be involved any more. The device found in Enfield was examined and found to be ‘viable’. According to the expert, if it had functioned it would have burnt for several minutes.

After the device was discovered in Enfield, somebody called the store and claimed there was a second device hidden there, and so the shop was evacuated. Somebody also rang the media.

Apart from Rayner and Sheppard, the other two people in the cell were both women. Sheppard didn’t make any anonymous phone calls about devices planted in Boots, so if this was a caller with a male voice, the only other person it could be was Rayner.

SHOTGUN

Sheppard didn’t go out with the intention of purchasing a shotgun. An armed robber he’d made friends with in prison asked him to look after the firearm. They dropped off the ammunition (some live and some not) at the same time as the gun.

They contacted him later from another country saying they were short of money and asked if he would buy it from them. He agreed to do this, thinking it could be useful for things like shooting out lights and cameras, or windows. He never intended to use it against a person. He thinks he paid between £100 and £200.

Asked why he kept the gun and the device/ components in his house, Sheppard says he doesn’t understand what was going on in his head at the time, and wonders if he had some kind of ‘death wish’ to have taken such a risk.

He says he and Rayner went out to Epping Forest together to test the gun.

1995 ARREST

When Sheppard’s home was raided the police recovered a double-barrelled shotgun (with only one working barrel) and some ammunition. We were shown a photo.

The Inquiry was shown a typed and handwritten note by Sheppard that included the paragraph:

‘we should trust our instincts above all else and if they lead us to sympathise with the use of lethal violence against animal torturers, then so be it.’

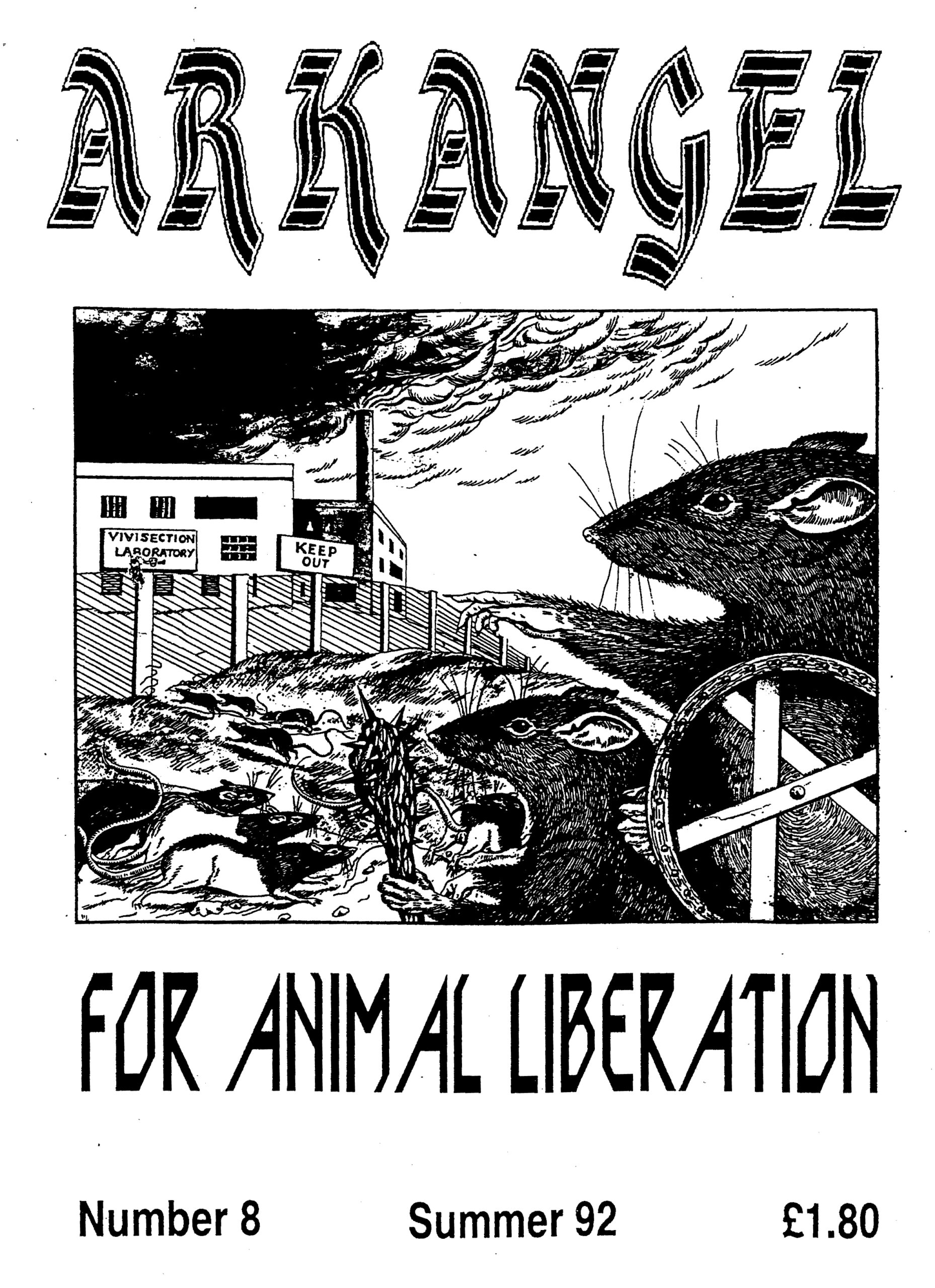

Sheppard says he wrote it in prison for an article in Arkangel magazine, that ‘maybe’ he would have had sympathy for someone who took lethal action against vivisectors, had it happened, but that he had no such intent himself.

It had the title ‘Follow the Force’. Sheppard explained he was referring to the ‘force within’ and the article ended by telling the reader to be true to themselves, which ‘99.95% of the time’ will tend to mean non-violence.

The cover of Arkangel issue 8, 1992

We were shown an intelligence report from 1 June 1995 attributed to Rayner (who claims it is a composite report, not written solely by him). It said Sheppard’s arrest on 26 May 1995 came as a shock to many animal rights activists, and that Geoff Sheppard intended to murder Professor Colin Blakemore, a neurobiologist and outspoken advocate of vivisection in medical research.

We were also shown the debrief of Rayner where he says Sheppard was looking after a shotgun and he didn’t know what to do with it. Rayner admitted Sheppard never told him that he planned to target Blakemore, but says that Blakemore was ‘public enemy number one within the anti-vivisection movement, there was constant talk by many activists, Geoff Sheppard included, of wanting to do him harm’.

Sheppard later appealed against his 1995 conviction, on the basis of Rayner’s involvement, encouragement and facilitation. In his grounds for appeal, he listed the ways in which Rayner had been involved: actively encouraging him to take part in actions, transporting him and others to actions, encouraging him to buy a shotgun and offering him money towards the purchase. Paul Gravett, Sheppard’s comrade, says he remembers Sheppard telling him about it at the time.

Sheppard now says Rayner didn’t encourage him to buy it, and didn’t even know about it until after it was paid for.

Geoff Sheppard was sentenced to seven years for his possession of a firearm and other items to be used for criminal damage. We were shown an authority document from Special Branch for Rayner to visit Sheppard in prison on the Isle of Wight in November 1996. Rayner also wrote to Sheppard in jail, with a number of letters exchanged.

This ended the questions, but not the questioning. The Inquiry went round in circles for a while, literally asking the exact same questions about the shotgun over and over, occasionally adding the prefix ‘are you sure’. It’s not clear what they thought this would achieve, and eventually they stopped.