UCPI Daily Report, 15 October 2024

Tranche 2, Phase 2, Day 2

15 October 2024

This summary covers the second day of ‘Tranche 2 Phase 2’, the new round hearings of the Undercover Policing Inquiry (UCPI), examining the animal rights-focused activities of the Metropolitan Police’s secret political unit, the Special Demonstration Squad, from 1983-92.

This summary covers the second day of ‘Tranche 2 Phase 2’, the new round hearings of the Undercover Policing Inquiry (UCPI), examining the animal rights-focused activities of the Metropolitan Police’s secret political unit, the Special Demonstration Squad, from 1983-92.

The UCPI is an independent, judge-led inquiry into undercover policing in England and Wales. Its main focus is the activity of two units who deployed long-term undercover officers into a variety of political groups; the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS, 1968-2008) and the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU, 1999-2011). Spycops from these units lived as activists for years at a time, spying on more than 1,000 groups.

Opening statements: Day 2

James Wood KC (Albert Beale; Gabrielle Bosley; Jane Hickman; Claire Hildreth; Hilary Moore; Rebecca Johnson; Robin Lane; Dave Morris: Geoff Shepherd; Paul Gravett; Helen Steel; Martyn Lowe)

Rajiv Menon KC (Friends of Freedom Press)

Dave Morris (McLibel Support Campaign)

Peter Weatherby KC (Hunt Saboteurs Association)

Sam Jacobs (Sharon Grant OBE; Stafford Scott)

Owen Greenhall (Joan Ruddock; Diane Abbott)

Fiona Murphy KC (The Category F Core Participants and TBS)

Kirsten Heaven (Non-Police Non-State Core Participants’ Co-ordinating Group)

1) James Wood KC

James Wood KC opens today’s hearing. He is speaking on behalf of 12 individuals represented by Hodge Jones and Allen:

- Albert Beale

- Gabrielle Bosley

- Jane Hickman

- Claire Hildreth

- Hilary Moore

- Rebecca Johnson

- Robin Lane

- Dave Morris

- Geoff Sheppard

- Paul Gravett

- Helen Steel

- Martyn Lowe

Their written Opening Statement goes into much more detail than his abbreviated oral submissions.

Wood began with some strong words about the officers of the Special Demonstration Squad, stating that they had:

‘committed some of the most serious abuses of state power against activists in modern times. They displayed, we say, a complete contempt for the basic rights and dignity of those they spied upon’.

Introductions

James Wood KC

Wood went on to introduce those he represents, all of whom had been targeted for their involvement in a wide range of groups, including London Greenpeace, the women’s peace movement, the Trafalgar Square Defendants Campaign and various animal rights groups.

He noted that their political views, and the tactics they chose to use, varied, but made the point that none of them encouraged or promoted any form of direct action that would cause harm to anyone.

He took some time to explain that London Greenpeace was a small, autonomous, group, established in 1971 and completely independent from the much larger Greenpeace organisation that now exists. He provided pen portraits of those who were active in the group in the 1980s and explained a little about their background and interests.

Both Albert Beale and Martyn Lowe could be described as ‘pacifists’ and had long been involved in anti-nuclear, peace campaigning and projects. Albert is due to give evidence on 11 November and Martyn is scheduled to appear on 4 November.

Dave Morris spoke later that morning, about the McLibel case in which he and Helen Steel were involved. Morris was also part of the Trafalgar Square Defendants Campaign, set up in the aftermath of the anti-Poll Tax demonstration that took place in central London in March 1990. He will be providing more evidence on 5 November.

Like Morris, Steel was also involved in a wide range of environmental and social justice groups over the years. She was also one of the women targeted and deceived into a long-term sexual relationship by one of the spycops, and so is part of the ‘Category H’ group. Helen will give evidence on 27 November.

Gabrielle Bosley got involved with London Greenpeace in the mid 1980s. She will give evidence on 7 November.

Paul Gravett became active at the same time. He was particularly interested in animal rights, and Wood went on to give an overview of the main groups that Gravett was involved in. These included Islington Animal Rights, London Boots Action Group (LBAG), and London Animal Action (LAA).

These groups were heavily infiltrated, both by a string of undercover police officers and by corporate spies (sent by the fur trade and vivisection industry). This Inquiry should examine how much information was being shared by the Special Demonstratoin Squad (SDS) with such players. Paul is due to give evidence on 13 November and 14 November.

Claire Hildreth was also passionate about animals, and involved in both LBAG and LAA. Hildreth formed a very close friendship with one of the spycops, HN1 ‘Matt Rayner’. She will appear on 11 December.

Wood turned next to a discussion of the Animal Liberation Front (ALF), a name used by people who took direct action to end animal suffering. He highlighted that one of the ALF’s principles was:

‘Reverence for Life: In all actions we take the utmost care that no harm should come to either human or animal life.’

The Animal Liberation Front Supporters Group (ALF-SG) had a press officer and an office, that produced publications. It did not take part in direct action.

Robin Lane served as press officer, and spokesperson for the group, between 1986-88. He has a long history of involvement in campaigning against animal abuse, and will give more evidence on 12 November.

Wood also mentioned Greenham Common women’s peace camp very briefly, as it has largely been covered by the evidence given by Jane Hickman, Hilary Moore and Rebecca Johnson during the Inquiry’s ‘Tranche 1 Phase 1’ hearings earlier this year (which examined spycops 1983-1992 who targeted groups not involved in animal rights).

Wood simply noted that there was no real justification for this SDS targeting; it was done on the ‘apparent whim’ of Margaret Thatcher.

Unsafe convictions

Two animal liberation activists in balaclavas, each holding a rescued white rabbit

Geoff Sheppard was convicted of two serious offences, and the safety of both convictions is cast in doubt by the conduct of two different undercovers. Geoff will give evidence on 14 November and 15 November.

In July 1987, times incendiary devices were planted at several Debenham’s stores, set to go off overnight when the buildings were locked and empty, with the intention of them triggering the store’s sprinkler systems and thereby causing huge economic damage to the furs that Debenhams controversially still sold at the time. HN10 Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’ was closely involved in initiating, planning and carrying out this action.

Sheppard went to prison for his part in the Debenham’s action. By the time he was released, Lambert had been made an SDS manager. However he had trained up a protégé, HN1 ‘Matt Rayner’, who encouraged Sheppard to return to activism and facilitated this by providing transport.

Sheppard’s second conviction, in 1995, was for a firearms offence. Rayner was lauded for providing the intelligence that led to this, but kept quiet about the role he had played in inciting Sheppard.

Had the SDS now decided that securing criminal convictions should be one of their roles? Wood contends that the SDS was ‘completely unsuited’ for this, given that they would always prioritise maintaining their cover over the criminal justice system. The involvement of the spycops was never disclosed to the courts and none of the usual safeguards were in place to ensure fair trials.

Legal privilege

In another issue which has come up in other Opening Statements, Wood explored the SDS’s ‘disdain’ for the criminal justice process, and lack of respect for the principles underpinning fair trial processes. SDS reports are full of details about what should have been considered ‘legally privileged material’.

Bob Lambert frequently visited Sheppard while he was in prison on remand. His reports contain information about the two co-defendants, the meetings they had with their lawyers, legal strategies and interpersonal conflicts.

Officer HN109 has told the Inquiry that he did not have a clear understanding of the concept of ‘legal privilege’ and so did not provide any guidance about to the undercovers he managed. It appears that none of the unit’s managers did, and such information was routinely recorded and retained.

Lambert’s lies

Firefighter in the wreckage of Debenham’s Luton store after 1987 incendiary device

Wood then returned to the Debenham’s story, going into more detail about Bob Lambert’s involvement. Lambert organised the first planning meeting, and argued that all Debenham’s stores, even those that didn’t sell fur, were legitimate targets.

He chose the Harrow branch as his target, and told the others that he had successfully planted a device there. £340,000 of damage was caused as a result. Overall, this anti-fur campaign is estimated to have cost Debenham’s around £4m. They stopped selling fur as a result.

Lambert continues to deny that he was directly involved in this action. Wood highlighted some of the discrepancies around this. Most shockingly, we heard for the first time today that CCTV footage from Harrow had been handed over to the (anti-terrorist) police who first attended the scene. It was then snatched by Special Branch officers, and has never been seen since.

From examining Lambert’s reports, it is clear that he was privy to far more information about these improvised incendiaries than he should have been, and that he curated the content of reports in a way that seems designed to mislead, and hide the extent of his direct involvement.

He claimed that these reports had been ‘sanitised’ by his managers but the relevant managers all deny doing so. The Inquiry has not been able to find all the reports that are believed to have been produced around this time.

However, there are SDS reports, identifying another person, ‘MSW’, as a ‘quartermaster’ for the Debenham’s campaign. ‘MSW’ was politically active between 1979-84, but says he had no knowledge of this serious crime, and did not even know the two men who were convicted or ‘Bob Robinson’ (Lambert) himself.

Lambert also made false, unfounded, allegations about Helen Steel being involved, which she denies. It seems that there may be a pattern of Lambert fabricating such stories to cover up his own deeds, and perhaps to advance his career.

Another witness, Chris Baillie, has come forward and told the Inquiry that Lambert had set him up to be arrested for criminal damage done by a third person to a butcher’s window. He will appear as a witness on 6 November.

It is clear that some people were suspicious about exactly what Lambert was up to, However, according to one of his managers, HN109:

‘the value in his intelligence potentially blinded more senior officers to how it was being obtained.’

Other SDS officers, like HN11 Mike Chitty ‘Mike Blake’, are known to have made similar comments.

Spycop Bob Lambert whilst undercover

Having later become an SDS manager himself, was Lambert able to destroy records relating to his own deployment and misconduct? Did he also ensure documents relating to Geoff Sheppard’s relationship with ‘Rayner’ were destroyed?

Interestingly, Lambert also told some activists that he carried out a similar, incendiary, action in Selfridge’s in August 1988.

The Inquiry will undoubtedly have lots of questions for Lambert when he finally appears between 2-5 December. It is estimated that his evidence will require four full days, longer than anyone else in this set of hearings.

Responding to the State

Wood made some comments about the Opening Statements we heard yesterday, in particular the one delivered by Peter Skelton on behalf of the Metropolitan Police.

Some of the mistakes made by the SDS are repeated, for example a failure to distinguish between various animal rights groups and those involved in them – labelling them all as ‘militant’ – along with attempts to exaggerate the impact of animal rights campaigners on those they protested.

Pickets outside shops, offices and homes may have been annoying or unwelcome, but at the time they were entirely lawful, and represented only a minor inconvenience, not a public order problem, and were hardly ‘terrifying’ in the way the police would have us all believe.

Even Bob Lambert is known to have written:

‘By late 1984, however the public order threat posed by various animal rights groups had all but disappeared.’

He notes that the only clients of his who were convicted of criminal offences had been encouraged and supported to take those actions by undercover officers.

It is clear that the SDS had a motive for portraying animal rights activists as ‘extremists’: this boosted their reputation and annual applications for increased funding. The Met continue to make these allegations because they seek to justify the highly intrusive infiltration of these groups.

What was the point?

These deployments were entirely speculative, and, Wood says, ‘entirely without justification’.

Despite spending years in the field, SDS officers didn’t always produce much useful intelligence in their reports, from the ‘cosy world of middle-class animal right campaigning’. Their deployments were not reviewed regularly.

Out of control

There was a lack of supervision or managerial control. Undercovers were given the freedom to operate as they wished, resulting in impropriety. Some (for example, HN2 Andy Coles ‘Any Davey’) took up positions of responsibility in the groups they targeted; others (like Bob Lambert) are known to have used their dominant personalities to influence the direction and activities of their target groups.

Most of the undercovers were older than those they spied on (having followed the advice they were given to ‘knock a few years off’ their real ages), and as a result younger activists often looked up to these men, and sought their advice about personal issues. There is evidence of them abusing their power, manipulating and ‘grooming’ people.

We heard that Claire Hildreth had confided in HN1 ‘Matt Rayner’ about her experiences with ‘creepy’ HN2 Andy Coles ‘Andy Davey’. He did not report Coles’s predatory behaviour to managers at the time.

This feeling of freedom undoubtedly extended to inciting and committing other serious crimes. The spycops believed they could act with impunity, and that their superiors would always have their backs.

Relationship with the Security Service (MI5)

According to Wood:

‘the evidence shows the Security Service and the SDS working alongside each other in close liason at all times’

The written Statement provides a great deal more detail about this. We know there were weekly meetings between the two. There was ‘intense political interest and influence’ in the units’ targets, including the groups listed above.

Re-traumatising the victims of these violations

Helen Steel at the Royal Courts of Justice

The final issue raised by Wood was about the ‘procedural difficulties’ faced by Helen Steel. He explained that she had been finally been given disclosure, but this meant she had been supplied with ‘many thousands of pages of material’ and asked to respond under extreme time pressure.

This material relates to the abuse she suffered, and includes many untrue and unproven allegations made about her by those abusers. Reading this has been extremely distressing and re-traumatising for her, but the Inquiry is not taking a ‘trauma-informed’ approach, and appears not to understand the significant and cumulative effect on Helen.

Her privacy has already been grossly violated by these officers, and now she (like other Non State Core Participants) is being expected to apply for privacy redactions within a very tight and inflexible time-frame.

He reminded the Inquiry’s Chair, Sir John Mitting, that the primary focus of this Inquiry should be to examine police misconduct, rather than unproven allegations made by former officers about their victims. The effectiveness of this Inquiry could well be impacted, by the inability of Helen and others to participate fully and effectively and provide crucial evidence.

A reminder

Wood drew Mitting’s attention to a European Court of Human Rights judgment, ironically from Helen’s own landmark case, Steel and Morris v United Kingdom.

This ruled that:

‘even small and informal campaign groups, such as London Greenpeace must be able to carry on their activities effectively and that there exists a strong public interest in enabling such groups and individuals outside the mainstream to contribute to the public debate by disseminating information and ideas’

He was sure that if the European Court had been aware of the state-sponsored intrusion of London Greenpeace at the time of this case, their words would have been ‘more forceful’. Democratic principles, such as freedom of speech and freedom of expression, do not seem to be recognised by the Met.

He went on to say that the SDS ‘represented the worst in our society’, the police were ‘incapable of properly balancing…civil and democratic rights’ and the unit should not have existed.

Mitting’s response

Having heard all of this, Mitting asked Wood to communicate to Helen that he acknowledges ‘her detailed and informative statement’, saying her evidence ‘is of the greatest assistance to me’.

He went on to add that he is ‘encouraged to hear’ that she will provide oral evidence during these hearings, but wants her to send in the documents she refers to it her witness statement, especially the photos, as soon as possible (before she gives evidence on 27 November).

2) Rajiv Menon KC

Rajiv Menon KC

Menon spoke again on Tuesday, this time on behalf of the Friends of Freedom Press (FFP).

They provided an Opening Statement and other evidence in the Inquiry’s Tranche 2 Phase 1 hearings earlier this year (Steve Sorba from FFP provided a witness statement and gave oral evidence in Week 2), about the SDS’s spying on the anarchist movement.

In particular HN85 Roger Pearce ‘Roger Thorley’ infiltrated the Freedom collective between 1979 and 1984 and later became a commander of Special Branch.

Today’s additional written Opening Statement addresses the evidence of SDS managers and other recently disclosed material.

Menon began by reiterating core participants’ profound concern that the Inquiry will be holding hearings in closed session, and that evidence will remain hidden from public scrutiny, perhaps forever, to protect the privacy of the officers and their families and the interests of the British state.

He then went on to consider the evidence of SDS managers, which raises important questions about SDS practices, where officers were allowed to cross what should have been operational red lines. Managers turned a blind eye, or sanctioned unconscionable behaviour, pointing out that the position of the Met becomes more and more untenable with every Tranche of Inquiry hearings:

‘the SDS did not serve any proper policing purpose’.

Historical overview

Menon noted that the decade under investigation in this tranche, from 1983 to 1992, is critical. The election of Margaret Thatcher in 1979 saw a shift in the political direction of the country. The post-war consensus between organised labour and capital was abandoned, leading to a showdown with the trade unions.

Miners and police clash during a strike at Tilmanstone Colliery, Kent, September 1984

The period was marked by struggles against racism and fascism, and the titanic struggle between the miners and the government. The gloves came off, and the police played a key role as enforcers of government will, known as ‘Maggie Thatcher’s Boot Boys’.

The SDS was an elite squad within Special Branch and they knew their officers would be protected at all costs. That meant attitudes changed.

During the 1980s we see reporting shift from a more old-fashioned objective style, to one that was exaggerated and inaccurate, intrusive, pejorative and laced with scurrilous fantasy. Officers and managers shared jokes inside the intelligence community echo chamber, at the expense of those on whom they spied.

Under the shadowy direction of MI5 the SDS created a culture whereby the supposed public order policing purpose was secondary to the real purpose of the SDS as a secret political police force.

Entitlement and arrests

Menon then examined evidence about the pay and overtime SDS officers felt they were entitled to.

‘SDS officers were overpaid and overvalued. SDS managers colluded in allowing their undercover officers too much independence, Roger Pearce’s mantra was: always defer to the officer in the field. This degree of autonomy spiralled out of control in the 1980s…

‘These undercover officers were likely to have been the highest paid officers in the Met, at least for their rank…

‘undercover officers could claim [overtime] for all their time in the pub or even in bed with an activist, supposedly gathering vital intelligence to protect the state, “Fucking for Queen and country” as Roger Pearce so crudely put it in his first novel.’

Menon also notes that during the Tranche 2 period now being examined (1983-1992), more SDS officers were arrested and ended up in court in their cover names. Although often for relatively minor offences, this was inevitably a stepping stone to more serious criminal involvement by SDS officers, as well as spying on defence lawyers.

It was also in direct contravention of Home Office instructions which unequivocally forbid any use of informants that may result in misleading a court.

None of the SDS managers appeared to regard the reporting on a legal advice as a problem.

Fantasy reporting

He then considered the problems inherent in MI5 using SDS undercover officers as human intelligence sources, often producing ‘fantasy reports for MI5’.

Menon notes evidence that senior managers felt that:

‘being a fantasist was a good trait for a undercover officer.’

‘Productive’ officers like Roger Pearce understood the game. Pearce would sex up his reports with lurid detail that played to the taste of his managers. His reporting style became the new SDS template for the 1980s.

HN115 Detective Chief Inspector Tony Wait says that MI5 received copies of virtually everything that SDS produced. They were ultimately serving the same political masters: a Conservative government, determined to crush the so-called enemy within.

The evidence of HN109 and HN11 Mike Chitty paints a further, worrying picture. HN10 Bob Lambert, HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’, HN8 (names restricted) and another unnamed undercover officer formed a ‘cabal’ within SDS. Lambert was the leader, and Menon notes,

‘There is reference in Eric Docker’s witness statement to the detective superintendent of C Squad, Dave Short, saying of Lambert: “The man’s out of control, you’ve lost him.”’

But was Lambert a rogue officer or was he playing a managed role, a participating agent provocateur? Lambert’s protégé, Dines, expressed the opinion that ‘rules are made to be broken’.

Lambert and Dines were regarded as the elite within a squad, that operated in a culture of impunity.

An inevitable problem

As an anarchist organisation that dates back to the 1880s, Freedom has a long historical memory. They say this is exactly where such state-sponsored spying always ends up, as agent provocateur activity which gets out of control or is carefully orchestrated with appropriate plausible deniability from the people in charge.

And so we come to ‘Operation Sparkler’, the prosecution of two Animal Liberation Front activists after improvised incendiary devices were placed in three Debenham’s stores, where Lambert is suspected of placing the third.

The investigation was taken over by SO12, Special Branch, away from SO13, the anti-terrorist squad. This appears abnormal as SO13 made the arrests. Was Special Branch trying to ensure that certain lines of enquiry were not pursued?

HN39 Eric Docker was promoted to detective chief inspector of SDS in October 1987, the month after the arrests. It was he who wrote up the commendation report for Bob Lambert.

Then, towards the end of the 1980s, things changed again. The Security Service Act was passed and the Service, also known as MI5, came slightly out of the shadows, as its activity was put on a statutory footing for the first time.

Margaret Thatcher was ousted, following the hugely successful anti-Poll Tax campaign in 1990, and MI5 had to do a full re-think. By 1992, there had been a change of focus and approach to ‘domestic extremism’.

This is addressed in the corporate witness statement of ‘Witness Y’. MI5 told Special Branch that they no longer needed all the ‘product’ that the SDS supplied.

This was the exact moment when there should have been a re-think, but instead of disbanding SDS, the Metropolitan Police Service and Special Branch doubled down, expanding their domestic surveillance operations, as we will see in Tranches 3 and 4 looking at later spycops’ activity, when the very officers who were the most responsible for the worst excesses of the SDS – Lambert, Dines and Coles – became the unit’s managers.

Menon ended his statement with the advice that the Inquiry needs to ask some searching questions, especially of those managers who were meant to be supervising the Lambert-Dines cabal:

‘Whether SDS activity was simply immoral or also criminal remains to be fully explored. On behalf of Freedom we suggest that there is now more than sufficient evidence from witnesses and documents for you, sir, to conclude that it was both.’

3) Dave Morris

Dave Morris

Next we heard from Dave Morris, the only Core Participant to make oral submissions (as he is appearing as a ‘litigant in person’), on behalf of the McLibel Support campaign.

The McLibel case ended up becoming the longest trial in English legal history. There were just two defendants, Dave Morris and Helen Steel.

Morris explained that Steel had been unable to contribute as much as she might have liked towards the accompanying written Opening Statement, due to the Inquiry’s delays in making disclosure to her and the unreasonable length of time allowed for her to go through this evidence. She has only managed to write a partial personal witness statement, but aims to produce another before giving oral evidence on 27 November.

It made a refreshing change to hear directly from one of the people who had been targeted by the spycops. Morris will give further oral evidence on 5 November.

Introducing the McLibel case

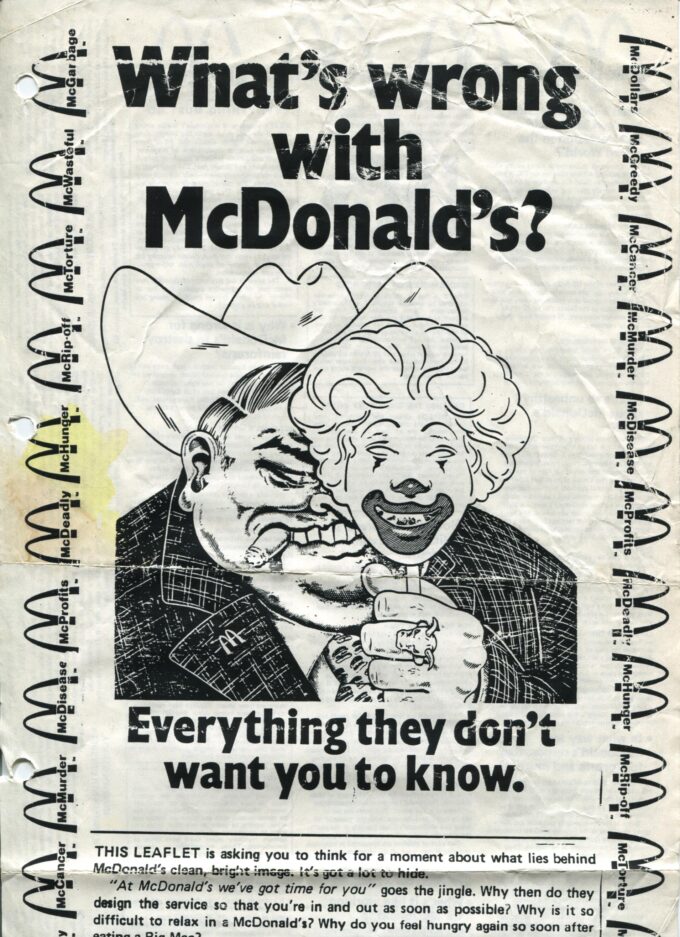

‘What’s Wrong With McDonalds?’ leaflet

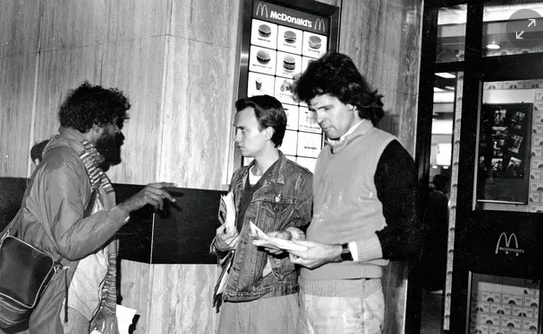

Dave explained some of the background to this infamous legal case. As life-long community activists, he and Steel were both involved in fighting for a better future, they were both involved in London Greenpeace, and along with other campaigners, distributed copies of a leaflet entitled ‘What’s wrong with McDonald’s?’

When the McDonald’s corporation threatened legal action, Steel and Morris refused to back down, and found themselves defending a libel case against a well-resourced, powerful multinational. They had to represent themselves, as legal aid was not available for such cases.

They relied on the help of volunteers to assist them, and received ‘pro bono’ advice from a young barrister named Keir Starmer for around ten years.

As a result of publicity around this ‘David and Goliath’ case, the leaflets which McDonald’s had set out to suppress were widely distributed for many years, all over the world.

We now know that the SDS not only infiltrated the campaign, they also collaborated secretly with McDonald’s before and during the case, something Morris condemned as ‘a serious miscarriage of justice’.

We also now know that one of the undercovers, HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’ engineered a long-term relationship with Steel – they even lived together – and this had been described the day before by the Inquiry’s own Counsel, David Barr KC, as Dines’s

‘cold, calculating emotional and sexual exploitation’

Infiltration

In the 1980s, London Greenpeace was a small group, campaigning about issues that were of widespread public concern, like the treatment of animals and workers and the environment. The trust and privacy of those involved was abused by the infiltration of SDS spies.

HN10 Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’ became a prominent and influential activist in what he described himself as ‘a peaceful campaigning group’. During his time undercover, he deceived four women into sexual relationships and fathered a child with one of them.

In 1986, he helped to create and distribute the original 6 page fact-sheet which asked ‘What’s wrong with McDonald’s?’ and provided the reader with a list of answers (everything from nutrition and diet, environmental damage, unethical advertising, worker exploitation, factory farming, global poverty…).

Morris brandished a copy on screen, and explained this was the leaflet that prompted McDonald’s to threaten libel action. A shorter version was produced and given out during the McLibel trial, with at least 3 million copies being printed and distributed in the UK.

Spycop and leaflet co-author Bob Lambert (right) with fellow London Greenpeace member Paul Gravett, leafleting McDonald’s Oxford Street, London, 1986

When HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’ joined the group, he also helped to produce and distribute these leaflets, organise events and protests, and become the group’s treasurer.

It wasn’t just these two SDS officers who infiltrated London Greenpeace; there were also at least six ‘inquiry agents’, corporate spies sent by McDonald’s to gather information between 1989-91.

McDonald’s hired former police officers for this operation, and one of them had a fraudulent sexual relationship with a member of the group, which lasted for around six months.

As a result of the intelligence gathered by the SDS and these inquiry agents, McDonald’s served libel writs on five named individuals in September 1990.

Three of the group felt they had no option but to pull out of what promised to be an expensive, unfair fight, leaving Morris and Steel to stand up to McDonald’s in court.

The case – including a full appeal – ran until 2005.

The pair went on to win a case against the British Government in the European Court of Human Rights, and were formally represented there by Keir Starmer there (as they received legal aid for this). That court ruled that the state had violated their right to a fair hearing and freedom of expression, but had no idea about the extent of the intrusion they had suffered.

Breaching legal privilege and spying on Starmer

Dines reported that the leaflet ‘is causing much concern within the corporation’, shortly before the McLibel writs were served. According to him:

‘Arrangements are in hand to monitor events arising from these legal proceedings’.

He went on to report on confidential discussions between the recipients of those writs and their lawyers.

In a later report he boasts:

‘It is accurate to say that I was “by the side” of Helen Steel and Dave Morris in 1991 and relaying the legal advice back to my bosses in the SDS’.

He used to collect Steel after she had attended legal strategy meetings with Starmer.

Secret unlawful collaboration between McDonald’s and the Met

It is clear that information flowed in both directions, between McDonald’s and the SDS.

McDonald’s recruited Sid Nicholson in 1983 as Head of Security. In his prior 31 year police career, he had worked in apartheid South Africa before coming to London and rising to the rank of Chief Superintendent in the Met, covering the Brixton area.

He was responsible for McDonald’s security and ran their spying operations. He brought in other former police officers, such as Terry Carroll (also from Brixton), who was hired as a Security Manager, and admitted in 2013:

‘I was aware that Sid would liaise with Special Branch officers about the protestors’.

He also recalled Sid telling him that there was a ‘Special Branch bloke’ inside London Greenpeace.

In 1990, he had sent Nicholson a memo, promising:

‘I will get onto Special Branch to get an assessment’.

Nicholson testified during McLibel that his security team were ‘all ex-police’, and it’s clear that this strategy meant they were all able to get hold of information from mates who were still on the force. One of the McDonald’s spies held two long meetings with a Special Branch officer in June 1990 to share private information.

Morris noted in passing that Bob Lambert had worked on Special Branch’s C Squad, with special responsibility for the Brixton area, while Nicholson was still in post.

A police ‘file note’ from 2002 (disclosed recently by the Inquiry) reveals that although HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’ was heavily involved in the anti-McDonald’s campaign in 1990, the SDS had made sure that his name

‘was deliberately omitted from the McDonald’s libel writ list’

Morris describes this as ‘blatant manipulation of the legal process’, and calls on the Inquiry to investigate the roles played by undercovers in this web of secret collaboration and subterfuge.

The search for the truth

SDS officer HN5 John Dines whilst undercover as ‘John Barker’

Dines began cynically faking a mental breakdown in 1991, and finally disappeared from Steel’s life the following year, telling her that he was going abroad. As a result, she suffered heartache and worry, and spent many years trying to find him.

By 1995, Lambert had been promoted to SDS manager, and was worried about the possibility of either Dines or the Commissioner being sub-poenaed to give evidence at the McLibel trial, if Steel were ever to discover the truth about her ex-partner.

By 1998 Steel and Morris knew only that Special Branch had provided their private details to McDonald’s, and successfully sued the police over this. In 2000, the Met offered to make a pay-out of £10,000, plus costs, rather than go through ‘a difficult and lengthy trial’.

Morris says now:

‘Had the true picture been known we may well have not settled the claim.’

The judgments of the High Court and the Court of Appeal found that much of what had been printed in the leaflet was true, and that McDonald’s had breached both employment and animal welfare legislation. However they were never prosecuted. Why not?

Consequences of the case

London Greenpeace never fully recovered after the McLibel case, and its activities gradually fizzled out.

Although the ‘McLibel Two’ won on some points, they also lost on some. As a result, Steel and Morris had damages of £60,000 awarded against them, which they refused to pay. Morris says the case:

‘certainly had real consequences. Not only Helen and myself, but also Keir had to put in years of unpaid and intense work to help defend the action’.

For Steel, the stress of fighting the case was magnified by the trauma of Dines’s fake breakdown, her concern and her efforts to trace him. She then had to deal with the additional trauma of gradually uncovering the shocking truth about his identity.

Morris says this case is another example of the police:

‘showing their utter disregard for the integrity of legal proceedings’.

4) Peter Weatherby KC

Peter Weatherby KC appeared on behalf of the Hunt Saboteurs Association (HSA).

Before talking about the activities of the HSA, Weatherby made clear:

‘there was no legitimate justification whatsoever for undercover policing targeting it as an organisation or its supporters or its activities or their families or their homes or their private and sexual lives…

‘undercover policing interfered with a fundamental constitutional and convention rights of Hunt Saboteurs Association supporters relating to freedoms to organise, assemble and act as well as their personal rights as autonomous individuals.’

He outlined various transgressions of undercovers, quoting SDS officer HN2 Andy Coles ‘Andy Davey’:

‘Misleading a court is something done by criminals and government ministers alike – we shouldn’t be squeamish about the ends justifying the means in our own case.’

This casual approach to misleading criminal courts is an affront to the rule of law. Managers knew and consented, and:

‘if ever this Inquiry needed evidence that the SDS was allowed to operate beyond any normal lawful limits, this is it… [SDS] was a political policing unit to which normal lawful limits were simply not recognised or applied.’

Hunt Saboteurs

The HSA was formed and still exists to prevent the killing of animals in blood sports. Its core activities were and are to take non-violent direct action to prevent such cruelty and to lobby government to enact laws to criminalise and stop activities such as fox-hunting and hare-coursing. Some supporters report illegal hunting to police and provide evidence for prosecutions, there’s nothing inherently unlawful about those core activities.

Opinion polls show the majority of the public is against blood sports and has been throughout at the whole history of the Hunt Saboteurs Association. The Hunting Act passed in 2004, cementing the HSA’s position on the right side of history.

It is a national association with democratic structures, which takes part in national lobbying. Activities against hunts are invariably through local groups.

The HSA has always believed in non-violence. This is a moral and a practical choice. Confrontation or violence are a distraction. To make a hunt ineffective, saboteurs lay false scents, blow hunting horns to draw hounds away, and make noise to cause wild animals to seek safety.

Weatherby notes:

‘Pursuing wild animals with dogs may well not have been unlawful during the period under consideration and neither was disrupting that cruel pursuit in the ways described.’

Conversely, hunt supporters often sought to deter and intimidate saboteurs through organised violence perpetrated by hired thugs. Hunt saboteurs have been killed and sustained serious injuries requiring hospital treatment. This is an important point which Weatherby addressed at some length and in more detail in his written statement.

Violence directed at hunt saboteurs was so severe that the HSA collated these experiences and submitted a written report entitled ‘Public order, private armies: Security guards of British hunts’ to the Home Affairs Select Committee investigating the use of private security firms. There was little subtlety in the campaigns by hunt supporters against hunt saboteurs and the threats were in plain sight.

Undercover officers witnessed the violent attacks on hunt sabs and on occasion reported on where the real threat lay. Managers refer in contemporaneous documentation to the risk of officers being injured by hunt supporters.

HN2 Andy Coles ‘Andy Davey’ stated:

‘I feared serious assault from terriermen or being shot at by irate farmers more than anything else during my tour.’

In 1992 the British Field Sports Society (BFSS) ran a campaign to encourage hunts to use so-called stewards to deter saboteurs.

In the words of BFSS spokesperson, Nick Herbert:

‘we’re going to start hunting the saboteurs.’

This left little to the imagination.

Herbert went on to become an MP and was policing minister between 2010 and 2012. In that role, he defended undercover officers having sex with women they spied on.

ITV news headline – ‘Nick Herbert: “It’s important police are allowed to have sex with activists”‘, 13 June 2012

He is now Lord Herbert and chair of the College of Policing, responsible for the authorised professional practice for undercover officers.

In this context, Weatherby examined whether the HSA were a public order threat. An SDS report from 1989 summed it up:

‘From a public order point of view the threat of violence these days comes more from supporters of the hunt rather than from the 20 to 30 saboteurs.’

Why then were the HSA made a target? The answer is politicised bias. Put simply, ‘Those associated with hunting had greater access to the corridors of power than those who opposed hunting.’

Weatherby referred to obvious and key areas of questions the HSA urge the Inquiry to focus on.

Justification

Any such deployments should be subject to precise justification based on a rigorous process, based on evidence properly recorded and regularly reviewed and supervised at a high level.

None of this appears to have occurred. There was no tenable justification for the deployments against the HSA.

Weatherby cited the 1995/1996 SDS annual report:

‘The emphasis that penetration of hunt sabotage groups is a means to an end rather than an end in itself in terms of SDS operations remains valid.’

Thus, from the SDS’s own mouthpiece, it seems their justification for infiltrating the HSA was a speculative attempt to identify people who might be involved in other acts. Could this means to an end infiltration ever be justifiable in principle? The HSA firmly refute that idea.

Proportionality

What proportionality exercises were conducted? Were legitimate aims identified at all? Is there evidence of any significant useful intelligence obtained at the time?

Weatherby notes that even if what he calls the ‘Animal Liberation Front excuse’ were accepted, most so-called ALF activity involved low-level criminal damage caused when rescuing animals or damage perhaps to butchers’ shops.

Instructions and training

What were the instructions to undercover officers? What was their training? What were their limitations, not only generally but on those target activities?

Weatherby pointed to undercover officers taking part in, encouraging or organising serious criminal activities; he notes that a number of the women personally violated in deceitful relationships were hunt saboteurs, and adds:

‘you’ll hear from witnesses who were befriended by undercover officers, they not only went to festivals and abroad with them, but they welcomed them into their own homes and families and introduced them to friends unaware of their true identities.’

Finally, he notes that police bias against hunt sabs often led to unlawful arrests. Many such detentions did not result in charges and not infrequently hunt saboteurs took successful civil claims.

Officers like Lambert, Dines and Coles were also arrested, which raises a number of uncomfortable issues. Did these officers infringe legal privilege? Were these arrests used as a means of enhancing the standing of undercover officers in their deployments? Did undercover officers mislead criminal courts?

‘The Inquiry must not only establish the facts concerning these violations of fundamental rights and affronts to the administration of justice, it must also establish accountability and bring to an end such unacceptable practices.’

5) Sam Jacobs

Sam Jacobs

Sam Jacobs appeared next, on behalf of Sharon Grant OBE (in relation to Bernie Grant) and Stafford Scott (Broadwater Farm Defence Committee)

There is an accompanying written Statement.

Jacobs made a brief oral statement, and referred the Inquiry to wider points made in the opening statement of the co-operating group of non-state non-police core participants, about shocking SDS mismanagement, culture and lack of accountability.

He notes that documents disclosed in this Tranche have important implications for all of his clients, including those whose evidence will be heard in Tranche 3 who, because of restriction orders have not yet had sight of the material.

Targeting

How groups or individuals were selected for targeting by the SDS remains opaque. Managers’ statements shed little light.

Only HN115 offers a detailed account of targets identified by the SDS, following consultation with the Security Service and senior managers from other squads.

Jacobs urges the Inquiry to consider:

‘the interests and concerns of the Metropolitan Police which will have informed the apparently amorphous targeting strategy.’

Like Scobie on Monday, Jacobs gives the example of a Special Branch report from January 1983, ‘Political extremism and a campaign for accountability within the Metropolitan Police’, which makes it plain the police viewed any attempt to bring accountability as subversive in itself.

The subversive aims of the Greater London Council included ensuring the police complaints procedure worked effectively. The report describes attempts to develop monitoring groups as ‘grandiose’, and ‘sinister’ and sought to discredit democratically elected officials as having extremist connections.

Jacobs concludes@

‘It is clear that the very notion of police accountability was viewed as problematic by Special Branch…

‘reporting on these groups and the various justice campaigns in the Tranche 2 period [1983-1992] and beyond was a deliberate objective.’

Sharon Grant OBE

Sharon Grant & Neville Lawrence deliver letter about spycops to the Home Office, 24 April 2018. It was ignored.

Managers’ witness evidence about reporting on elected officials is inconsistent and has served only to muddy the waters and to raise further concerns.

The 1 June 1988 briefing paper produced for the Security Service’s Management Board on counter subversion refers to F Branch monitoring of various mainstream political groups, including the Labour Party.

This casts doubt on managers’ claims that there should be no active reporting on MPs or that reporting on members of Parliament by the SDS and Special Branch was either discouraged or was simply incidental.

Reports on Bernie Grant and other MPs were frequently supplied to the Security Service. Special Branch had a direct interest in the activities of elected politicians and they did report on their activities.

The 1983 report on police accountability references dozens of elected officials, including Bernie Grant, with (inaccurate) details of their purported political beliefs and allegiances.

The interest of the Metropolitan Police and the SDS appeared to be at its highest when Bernie Grant was critical of policing methods or of the police. The Met is most concerned with its own reputation and using Special Branch reporting to defend itself from criticism.

Sharon Grant has long-held concerns that the Met was the source of unfavourable media stories about her husband and the evidence disclosed to date heightens those concerns.

Stafford Scott

Stafford Scott

Managers’ evidence has exacerbated Scott’s concerns about why he and the Broadwater Farm Defence Committee were reported on by undercover officers. The Metropolitan Police made it clear that they regarded any campaigns for police accountability and justice to be subversive by their very nature, and Scott was involved in precisely this area of work in his community.

Managers’ statements insist that reporting on such groups was a by-product of reporting on the other political groups, and so was justified in the interests of public order.

However, not one single report on Stafford Scott or of the activities of Broadwater Farm Defence Committee that raises any legitimate concerns about public order, or evidences manipulation of the group by political activists.

Managers approved and submitted reports by undercover officers, yet did not confront or address the racism that was so clearly prevalent. Two of the reports describe speakers at public meetings as ‘negroes’.

HN78 Trevor Morris ‘Anthony “Bobby” Lewis’ is referred to as ‘a coloured potential recruit’.

It is clear that he was regarded as a useful asset, who would be able to obtain access that might not be available to other undercover officers.

HN59 states that managers would edit reports, sometimes removing words or phrases. HN109 states that he had an editorial role over the reports, removing irrelevant or judgmental comments. Yet explicitly racist language was not edited.

Undercovers’ and managers’ constant refrain is that the language used in reports was reflective of its time and should not be judged by today’s standards:

‘yet this is language that is more in tune with the segregated American deep south than London in the 1980s.’

The language and attitude expressed in the reports, which went unchallenged by managers, shows that minorities were regarded as a threat by the Metropolitan Police whenever they sought to organise around issues of justice and accountability.

The opening statement of the Met Commissioner to Tranche 2 Phase 1 described reporting on social justice campaigns, family campaigns and community organisations as ‘indefensible’, resulting from:

‘a critical failure on the part of its managers’.

Scott asks the Chair to be aware that these attitudes and behaviours do not operate in a vacuum, and the critical failures of the SDS managers were also critical failures on the part of the Metropolitan Police and the Home Office, and not just the individuals giving evidence to this Inquiry.

6) Owen Greenhall

Owen Greenhall

Owen Greenhall appeared on behalf of Diane Abbott OBE and Dame Joan Ruddock, who have supplied a written Opening Statement.

Diane Abbott has been a leading anti-racism campaigner for decades. In 1987 she became the first black woman to be an MP, representing Hackney North and Stoke Newington. Re-elected in 2024, she is now the longest-standing continuously serving female MP, the ‘Mother of the House’.

The Right Honourable Dame Joan Ruddock PC is an anti-apartheid campaigner and former chair of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND). She was MP for Deptford from 1987 to 2015 and held several ministerial positions, including Minister for Women, Minister for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, and Minister for Energy and Climate Change.

Greenhall explained that both Abbott and Ruddock were subject to SDS reporting and they share a number of concerns (expressed in their opening to Tranche 2 Phase 1 earlier this year and expanded here)

(i) The targeting of MPs and the adequacy of disclosure.

(ii) Concerns over racial discrimination in the activities of the SDS.

(iii) Concerns over the use of information gathered by the SDS.

(iv) Procedural issues related to the Inquiry.

The targeting of MPs

Reporting on MPs was a central concern in the creation of this Inquiry, and was debated in Parliament in March 2015.

The response from the Minister for Policing Criminal Justice and Victims, Mike Penning, was that he would:

‘do everything I can to make sure that the documents are released… We have to find out exactly what went on.’

Spying on MPs raises serious concerns over the erosion of the Wilson doctrine against police surveillance of Members of Parliament, inappropriate collection of personal information and interference with the democratic process. Greenhall pointed out:

‘It’s notable that only Labour MPs appear to have been targeted.’

Former undercover officer Peter Francis has revealed that Special Branch files on MPs were typically ‘very extensive’ and often contained personal and private information.

HN78 Trevor Morris ‘Anthony “Bobby” Lewis’ was asked whether he ever saw a file on an elected politician. He replied:

‘I was going to say hundreds. Many, many, many… they are all marked ‘Secret’… probably top secret.’

Trevor Morris published a book ‘Black Ops: The Incredible True Story of a British secret agent’ using the pseudonym Carlton King.

Greenhall quoted from that book:

‘It is the job of the Security Service to vet and assess senior politicians; the Branch assisted with this duty where and when required. When the Branch came across intelligence relating to politicians (through its agents, desk officers or SDS operatives et cetera)… it would pass this intelligence to the Security Service.’

Yet very little of this reporting has actually been disclosed by the Inquiry to date (when questioning Morris they didn’t menton his book and later absurdly said MI5 had forced them not to admit he was in fact Carlton King).

Core participants ask that these discrepancies are investigated to ensure that the Inquiry uncovers the full truth of what took place.

Racial discrimination in the activities of the SDS

Greenhall quoted Home Office guidelines produced right at the start of this Tranche, in 1984:

‘Special Branch investigations into subversive activities in particularly sensitive fields, for example in educational establishments, in trade unions, in industry and among racial minorities, must be conducted with particular care so as to avoid any suggestion that Special Branches are investigating matters involving the legitimate expression of views…

‘It is not the function of the force Special Branch to investigate individuals and groups merely because their policies are unpalatable, or because they are highly critical of the police, or because they want to transform the present system of police accountability.’

Yet there was extensive reporting on racial justice campaigns and police accountability issues.

Indeed, Managers appear to have been unaware of the guidelines. Annual reports for the SDS indicate that campaigns on racial issues were a key aspect of targeting, the Anti-Nazi League, a variety of local anti-racist and anti-fascist groups and predominantly black family justice campaigns regularly feature.

The purported justification – concern that these groups might be taken over by other organisations – is racist, assuming black-led organisations could not preserve their own independence.

The use of information gathered by the SDS

Throughout the Tranche 2 period (1983-1992), the SDS worked hand in glove with the Security Service. One primary purpose of the Security Service was vetting. The SDS played a crucial part in this.

‘Witness Y’ accepts:

‘it is in my view highly likely that some (possibly most) of the information sought from SDS officers was sought in order to be used for vetting purposes’

Security Service influence on targeting is confirmed by SDS managers. HN115 Tony Wait states:

‘The Security Service influenced our targeting decisions quite a lot. Most of our deployments were in agreement with them. We would always seek their views before deciding on new targets.’

Security Service requests were often coupled to political and diplomatic concerns at the time (see our report on the Opening Statement on behalf of CND).

As Carlton King, aka HN78 Trevor Morris, writes:

‘the Branch was only one cog in the British state’s domestic national security apparatus, the Security Service (MI5) was an even more central component, as was the Home Office, the judiciary, the press and of course the politicians, in particular cabinet-level government ministers who sat at the centre of this machine and could therefore tweak it to their advantage.’

That past involvement coming in one of the largest anti-nuclear movements could inhibit the future career of those concerned is reminiscent of the authoritarian regimes which the SDS and Security Services claimed to be fighting against.

Greenhall therefore asked the Inquiry to:

‘fully explore the use that was made of SDS reports for vetting purposes, particularly in relation to politicians and civil servants.’

Procedural issues

Greenhall echoed the concerns raised by many other core participants.

‘The disclosure and Rule 9 process for Tranche 2 has been heavily delayed for the non-state core participants and that has had the effect of marginalising their impact and in many respects excluding them from effective participation.

‘The impact of these delays has almost exclusively been to the detriment of non-state core participants… limitations on attendance at hearings has hindered the engagement of the core participants in the Inquiry…

‘The Inquiry is asked to ensure that procedural issues do not reduce the accountability of those responsible for the SDS… [and] to take steps to minimise the prejudice to non-state core participants affected by the delays.’

7) Fiona Murphy KC

Fiona Murphy KC

After lunch, we heard from Fiona Murphy KC, representing ‘TBS’ and ‘Category F’ Core Participants (people deceived into relationships by undercover officers)

‘TBS’

Murphy spoke first on behalf of TBS, whose mother ‘Jacqui’ had a long-term sexual relationship with HN10 Bob Lambert.

TBS was born in 1985 and his father, posing as a committed animal rights activist using the name ‘Bob Robinson’ (an identity Lambert stole from a dead child), was involved in his life until 1988. Then he disappeared, abandoning TBS, who did not learn of the true identity of his father for a further 24 years. He has provided a written statement to the Inquiry.

TBS has given powerful testimony, setting out the difficult process of reconciling himself to his biological father’s absence, his tragic attempts to learn more about the fiction that was ‘Bob Robinson’, to identify with that fiction, and how TBS has struggled to come to terms with the reality that his understanding of his parentage was based on a lie.

TBS complains that the treatment of him by the Inquiry has not been fair, has not been consistent, has not been predictable and has not facilitated him in being heard in relation to decisions that affect him.

He aligns with the remarks of other core participants about issues arising from delay and disclosure. The unorthodox approach to the marshalling of evidence taken by this public inquiry runs the significant risk of the truth being obscured.

The Inquiry also chose to limit TBS’s legal funding, locking his lawyers out from considering the evidence of civilian witnesses, including the evidence of his own mother.

‘These experiences have undermined TBS’s confidence in your Inquiry, sir, and he endorses the analysis of the non-state non-police core participants opening statement that this is an Inquiry in crisis.’

The Commissioner’s responsibility

TBS has outlined in his witness statement:

‘The Metropolitan Police Service do not seem as an organisation to accept that … they had responsibility to try to minimise the impact, to hold their hands up, to accept that they had allowed a toxic culture to develop which led to these issues. To acknowledge the wrongs done and to provide resources to help the victims, such as me, to access specialist psychiatric and psychological help.

‘It feels scary that as an organisation the MPS [Metropolitan Police Service] were happy for me to go through my whole life without knowing the true identity of my biological father. And if it were not for the work of activists and journalists I would probably never have known the truth or had the chance to meet my biological father.

The Metropolitan Police Service simply left me alone to deal with all of this, both before and after I learned of Bob Lambert’s true identity.’

The Commissioner of the Met apologised to TBS in his opening statement for the distress he has suffered growing up not knowing his true parentage, for the fact that the Metropolitan Police should not have allowed Bob Lambert to behave in the way that he did, and committing to ensure that TBS receives answers to his questions during this Inquiry.

Bob Lambert, 2013

The apology addresses Bob Lambert’s conduct, it does not address the organisational responsibility of those who knew of TBS’s existence in the years and decades following his birth. It does not address the Commissioner’s own failings in relation to TBS in the period leading to and following Bob Lambert’s exposure.

TBS invites the Metropolitan Police to provide a corporate evidential witness statement deposed in full compliance with the Commissioner’s duty of candour, addressing the chronology of the organisation’s awareness of the developing public interest in the SDS in general and Bob Lambert in particular.

When did the Met became aware that there was a significant likelihood that Bob Lambert’s true identity would be disclosed publicly? When was it obvious that Bob Lambert’s identity would become known to TBS? What decisions were taken regarding the need to notify Bob Lambert’s identity to TBS before his mother pieced the evidence together from press reports?

Lambert was exposed on 15 October 2011. He made apologies on 23 October to London Greenpeace and to Belinda Harvey, who he had deceived into a relationship. He made no mention of Jacqui or TBS. He made no effort to contact them.

Eight months later, by chance, Jacqui stumbled on the truth when she saw an article in the Daily Mail on 12 June 2012.

‘It was unconscionable for the Metropolitan Police Service to leave TBS and his mother to find out the truth in the manner in which they did.’

Murphy set out the legal framework on the Rights of the Child, citing pronouncements at the highest judicial level that the best interests of children are not served by the concealment of truth. On the contrary, it causes mental and psychological suffering which does not diminish with age.

Knowledge of one’s true identity positively contributes to personal development, to one’s sense of self and there are also of course important practical consequences, including in relation to knowledge of potential hereditary medical conditions.

Had the Metropolitan Police sought advice at the time of TBS’s birth or at any stage subsequently, they would have been advised that notifying TBS of his true parentage was in his best interests.

TBS will learn facts about his childhood and early development during this Inquiry. The decision to restrict his legal funding is therefore particularly cruel. TBS has had to suppress his identification with the non-existent ‘Bob Robinson’ and to come to terms with the true identity of Bob Lambert.

In his own words:

‘The father that disappeared was a fabrication, and I’ve had to grapple with deconstructing that myth that my life was built around.’

The impact upon TBS of this deception has been profound and it endures to this day.

Murphy highlighted some details from the evidence, such as the decision to obscure Bob Lambert’s identity and whereabouts at the time when ‘Jacqui’ was seeking to have TBS adopted by her new husband, misleading social services and the family courts. The name of the individual who did this has been restricted by the Inquiry, preventing publication.

She also notes:

‘Bob Lambert’s deployment as “Bob Robinson” continued for a further three years after TBS’s birth, but that he was permitted to return in a managerial role. Despite his having demonstrated in these starkest terms that his professionalism and propriety could not be relied upon and that he posed a significant risk of ongoing harm to those among whom he was deployed.’

Murphy then made a chilling appeal to the Inquiry:

‘There is evidence, sir, that we ask you to consider with care that there were other children born of these abusive relationships.

‘At a bare minimum, sir, it is the Commissioner’s responsibility to assure you that no other human being is living a life with the truth obscured from him or her as it was from TBS for more than two decades.’

Families whose loved ones’ identites were stolen

‘Category F’ are the families whose loved ones’ identities were stolen by the Special Demonstration Squad and its officers. They have also provided a written Statement.

The Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police publicly apologised to the families on Monday, adding that misconduct by officers while using the dead children’s identities was disrespectful to their memories, and the Commissioner has apologised to all the families for this and for the Metropolitan Police’s failure to stop that misconduct from occurring.

Murphy noted that the apology was welcome, but detailed the inadequacies of the Met’s response:

‘What is apparent is that the risk to families from such events was never considered, although it ought to have been. This is but one example of the SDS’s deplorable myopia.’

Senior officers within the Metropolitan Police were fully aware of the practice but did not take any steps to stop it for two decades, nor to close the SDS.

Few officers turned their minds to the inevitable impact on the families or the devastation that this practice has wrought on their families, already made vulnerable by the premature loss of a child or a young adult, and how the memories they all cherish have been tainted and tarnished by it.

The families participating in this tranche covering the period between 1983 and 1992 are:

• Frank Bennett and Honor Robson in relation to the theft and abuse of their brother Michael Hartley’s identity.

• Faith Mason, in relation to her son Neil Martin.

• Marva and Judy Lewis in relation to their brother Anthony Lewis.

• Kaden Blake, in relation to her brother Matthew Rayner.

They represent only a small proportion of the victims of identity theft by the Metropolitan Police in this period.

![Frank Bennett and Honor Robson, half-brother and sister of Michael Hartley [pic: Mark Waugh]](https://campaignopposingpolicesurveillance.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Honor-Robson-and-Frank-Bennett-scaled.jpg)

Frank Bennett and Honor Robson, half-brother and sister of Michael Hartley (pic: Mark Waugh)

They are concerned that in taking a child’s identity the officers went on to research and use details from the families’ private and family lives, so as to test their identity choice and to build their ‘legends’.

Meanwhile, no care was given to the risks to which the families were thereby themselves exposed.

Officers went far beyond acceptable conduct, seducing women, inveigling themselves into the lives of others, attending parties and weddings and even celebrating the birthdays of dead children as if they were their own. They committed criminal offences and appeared in court as witnesses or defendants in the names of dead children’s names.

They undermined lawful and legitimate protest movements. For the Marva Lewis and her family it was especially bitter to learn that HN78 Trevor Morris ‘Anthony “Bobby” Lews’ sought to undermine campaigns for racial justice while:

‘pretending to be my brother… he had stolen the identity of a deceased young black boy and his work undercover contributed to undermining the investigation into the racist murder of another black boy, Stephen Lawrence.’

‘The restricted family’

The families registered their regret and disappointment with the Inquiry. They are concerned that onerous restriction orders over historical practices are impeding the Inquiry’s investigations.

Many officers continue to enjoy anonymity, to the dismay of the families. This means it is the dead child’s identity with which their misconduct will be forever associated, and not the identity of the officer who was responsible.

The Chair has said that any attempt to challenge the restrictions, which were applied without reference to the families, is ‘discouraged’ and:

‘would almost certainly result in the existing restrictions being upheld… [and it’s] very unlikely that the Inquiry would extend funding for the purposes of any such scrutiny’.

The families have not been placed on an equal footing to the police core participants, and the Inquiry is failing to comply with the principle of open justice.

These problems are at their most acute in relation to ‘the restricted family’, a family who have been forced to participate in this Inquiry anonymously by reason of a restriction order covering their own name, to protect the identity of the officer who stole it.

They have been silenced and disempowered, denied the opportunity to speak openly about the trauma they have suffered, and their hopes that this Inquiry might expose the truth and achieve a measure of accountability have rapidly faded.

8) Kirsten Heaven

Kirsten Heaven

Our last speaker of the day, Kirsten Heaven appeared on behalf of ‘the co-operating group of NPSCPs’ – this means all the Non-Police Non-State Core Participants in this Inquiry, whose lawyers try to work together to represent everyone’s shared interests.

They produced a lengthy written Opening Statement for Tranche 2 Phase 2, in addition to the individual and group statements many of these people have made.

Initial observations

She pointed out that at the same time as making various apologies for the actions of undercover officers and ‘systemic management failings’ in yesterday’s Opening Statement, the Met also sought to persuade Mitting that the Inquiry should really now focus its attention on what they call the ‘primary question’: whether or not the spycops deployments were justified, rather than exploring the way these undercovers behaved.

She said:

‘Put simply, abhorrent behaviour and systemic managerial failure are matters that clearly go to the heart of the question of justification’

The Met are ‘wrong on this issue’, she added.

She then reminded Mitting of how the Investigatory Powers Tribunal dealt with this issue in the case brought by Kate Wilson (one of the women deceived by spycop EN12 Mark Kennedy ‘Mark Stone’).

The ensuing judgment from that case was highly critical of the ‘broad, open-ended authorisations’ used by the spycops units. These deployments were speculative ‘fishing operations’ and resulted in extensive collateral intrusion. They cannot be justified.

‘Abhorrent, abusive, cruel and morally repugnant’

Spycop Andy Coles undercover in the 1990s, and as a Conservative councillor in 2016

The four undercover officers that we’ll hear most about in this set of hearings have still not shown any real remorse, for the impact of what Heaven described as ‘the most abhorrent, abusive, cruel and morally repugnant behaviour in the history of the SDS’.

For example, HN2 Andy Coles ‘Andy Davey’ continues to deny that he – as a 32 year old married man – groomed a vulnerable teenager, Jessica, into a sexual relationship, pretending to be much younger than he actually was. The Met accept that ‘Jessica’ has been telling the truth.

The Inquiry must be sceptical about any evidence it hears from these men. Heaven continued by skewering the laughable idea that these spycops might still have reputations worth protecting.

Coles has claimed that ‘Jessica’ had a ‘father issue’ and was ‘obsessed’ with him. Since his identity was uncovered, by activists, multiple women have come forward to report similar stories of his creepy, predatory, ‘sex pest’ behaviour. He has made denigrating comments about some of these women too.

He was a married man, supposedly trying for a baby with his wife at the same time as grooming and sexually abusing a much younger activist.

HN10 Bob Lambert, after leaving the police, tried to reinvent himself as a respectable academic lecturer.

Bob Lambert receiving an award from the Islamic Human Rights Commission, 2007

Coles, described as ‘another aspiring novelist’, went on to become a Tory party councillor in Peterborough, Deputy Police & Crime Commissioner for Cambridgeshire, and even a school governor.

At one point he endorsed a campaign to protect young people from sexual exploitation despite being a perpetrator of it himself.

Unlike Lambert, Coles did not receive an MBE or a Police Commendation for his work in the SDS, and is known to have complained about not being given the recognition he felt he deserved for his ‘sacrifice’.

‘An elite undercover officer’

We have heard about a ‘cabal’ centred around Lambert, a group of men who saw themselves as a superior elite group within a special secret squad, fiercely loyal to each other.

By all accounts, Lambert himself is an over-entitled, self-promoting, arrogant man, described by HN109 as a ‘charismatic attention seeker’ and by former undercover colleague HN11 Mike Chitty ‘Mike Blake’ as ‘a professional liar’.

Andy Coles promoting the Children’s Society’s ‘Seriously Awkward’ campaign to protect older teenagers from sexual exploitation

He has shown no remorse for the cruel and abusive deception of ‘Jacqui’, or the three other women he had relationships with, claiming now that he did not intend to ‘target’ them, just succumbed to ‘weakness and irresponsibility’.

The ‘Category H’ Opening Statement suggests that Lambert may well have been motivated by a desire to seek out extra-marital sex with a younger woman, and notes that he has not returned the awards he was given for his contributions to policing.

Lambert has continued to use his skills of ‘deception and duplicity’ in his academic career. Despite stating that the animal rights movement was a ‘very serious business’, suggesting that these were dangerous people, he used to take his baby son along to meetings with these activists.

Lambert is known as a manipulative figure, who has already used a range of tactics to deflect criticism of his unethical behaviour and try to control the narrative. He is likely to go to great lengths to defend his reputation, and may well try to feign contrition. Hopefully Mitting will keep this in mind when he hears Lambert give evidence in December.

Lambert has hinted that he might publish a book about his experiences one day, and Heaven suggests that the Inquiry investigate the existence of a draft.

Rather than seeking to understand the serious impact the spycops’ actions had on those they targeted, Lambert seems to have treated many aspects of the SDS as a big joke. Even HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’, probably his closest friend in the unit, said that you don’t get a pointed answer from Lambert ‘unless you ask him a pointed question’.

Lambert rose through the ranks to become an SDS manager, then left the force in 2007. Sir Ian Blair, the Met’s Commissioner at the time, attended his retirement party. We still don’t know how much he and other senior cops knew about the way that Lambert operated, and if they bothered asking questions to find out how the SDS was obtaining its intelligence.

It’s all very well for police lawyers to turn up at this Inquiry with yet more ‘apologies’ for the spycops’ abuses, but we need to hear evidence from these senior officers.

‘Rules are make to be broken’

Dines and Lambert were very close, and frequently praised each other. They seem to have had a lot in common, including a deep-seated misogyny and lack of respect for activists, especially women, or their own wives.

Helen Steel (right) confronts ex-spycop John Dines, Sydney, March 2016

Other officers say that HN5 John Dines was very competitive, a ‘gong hunter’, who ‘wanted to be a gold star SDS officer’ and sought notoriety. It seems likely that this last wish will be granted.

Dines made many disparaging remarks about his time undercover (saying he found it ‘unpleasant, miserable and boring’) and about those he targeted, including Helen Steel. He professed to be in love with her, but coldly stated that he ‘couldn’t give a rats’ about the impact on her of his deception and the way in which he disappeared from her life.

Like Lambert, Dines received a police commendation. He did not want his wife to attend the ceremony in 1992.

Dines has refused to provide oral evidence to this Inquiry, so will not be appearing during these hearings.

Back in 2003, the Met paid out a huge sum of money to enable Dines to relocate his family from New Zealand to Australia. This was due to their fears that Helen Steel – after years of dogged research on her part – would succeed in tracking him down.

It seems that the police knew enough about his misconduct to realise that this could have resulted in a civil claim against the force. The 2003 BBC ‘True Spies’ documentary series had helped to confirm her suspicions about Dines and his true identity.

As well as demanding money for relocation costs, and compensation for the effect on his new career (as an extremely well paid barrister, who often took on cases defending radical activists in the New Zealand courts) Dines asked his former colleagues at the Yard to write him references and help him find new work in Australia.

The fourth officer discussed by Heaven was HN1 ‘Matt Rayner’. He also deceived a woman, Denise Fuller, into a romantic and sexual relationship that lasted around one year. Denise is due to give evidence on 6 January 2025.

Rayner knew that fellow officer Andy Coles had tried to sexually assault a woman, but did not report this incident to the SDS managers.

Loyalty and lies

We’ll be hearing evidence from some of the unit’s managers later in this Tranche (in January 2025).

When SDS officers have spoken publicly about the unit in the past (for example, in ‘True Spies’) others clearly saw this as a ’betrayal’ of the SDS’s secret status.

Heaven commented earlier about officers being ‘selective’ in their evidence and what they chose to reveal to this Inquiry. It seems that many of them still have a strong sense of loyalty to each other.

Their employers, the Met police, have now made it very clear that they consider some of the problems associated with the unit to have been caused by the managers’:

‘failure to lead the SDS properly and effectively’.

They have been admissions of failings in terms of welfare, discipline and misconduct; a lack of proper training; a lack of scrutiny or oversight; a failure to maintain professional standards or to ensure that reporting was appropriate or ethical.

Heaven points out that SDS managers should not allow any perceived loyalty – towards either the Met or the officers they managed – prevent them from providing honest answers to this Inquiry. Some undercovers (including Lambert and Coles) have already made comments critical of their managers, in an attempt to shift blame away from themselves.