Tranche 1, Phase 2, Day 11

6 May 2021

Summary of evidence:

‘Jimmy Pickford’ (HN300, 1974-77)

‘Barry / Desmond Loader’ (HN13, 1975-78)

Introduction of associated documents:

‘Geoff Wallace’ (HN296, 1975-78)

Evidence from witness:

Celia Stubbs

Today’s hearing of the Undercover Policing Inquiry started with the reading of witness statements of undercover officers that could not or did not want to appear in person.

‘Jimmy Pickford’ (HN300, 1974-77)

‘Jimmy Pickford‘ (HN300, 1974-77) infiltrated a number of groups, including anarchist ones, like the South London branches of the Anarchist Workers Association (AWA) and the Federation of London Anarchist Groups (FLAG).

He spent a year in Special Branch – including ‘C Squad’, the left-wing surveillance section – before joining the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) in the summer of 1974. He started off in the back-room, and by October was ready to be sent in to the ‘field’.

His first reports show that he targeted radical newspapers (including ‘Freedom’, ‘Lower Down’, ‘Up Against the Law’ and ‘Pavement’) as well as local, grass-roots groups around Battersea and Wandsworth in South West London.

These included the Battersea Park Action Group (BPAG), the Battersea Redevelopment Action Group (BRAG), and the Battersea & Wandsworth Trades Council Anti-Fascist Committee.

Pickford met an (unnamed) woman during his deployment (in his cover identity), with whom he had a sexual relationship. His expressed desire to tell her his real identity led to his withdrawal from active deployment in 1976. He has since died, so will not be giving evidence.

FAMILY STATEMENT

However, the Inquiry has received a statement from Pickford’s second wife and children, detailing the impact of his undercover work on them.

The family are concerned that publicity from the Inquiry will interfere with their right to a private life, so have asked for his real name to be restricted.

They are concerned about ‘unscrupulous individuals’ who were around him in later life, who might try to ‘cash in’ on this association by selling (untrue) stories to the press. They are also concerned about the possibility of other police officers making connections due to his undercover work, and sharing details of his deployments.

They say that before becoming an undercover officer, ‘Pickford’ was supplied with assurances that his true identity would never be disclosed, to ensure the safety of both him and his family:

‘This was of paramount importance to him and he mentioned this to us many times’

He taught his children to be vigilant, not divulge information, and to be suspicious of anyone seeking information, no matter how innocuous it seemed. He talked about other police work, but never his undercover deployment. After this ended, he took public-facing roles. His family believe this is because he felt his identity was secure.

They believe he infiltrated at least two groups that represented high levels of risk and danger. One of these groups remains active now, in another form. They are worried that people from these groups will try to target the family, physically or via the media/ online. They believe they could easily be tracked down.

UNDERCOVER

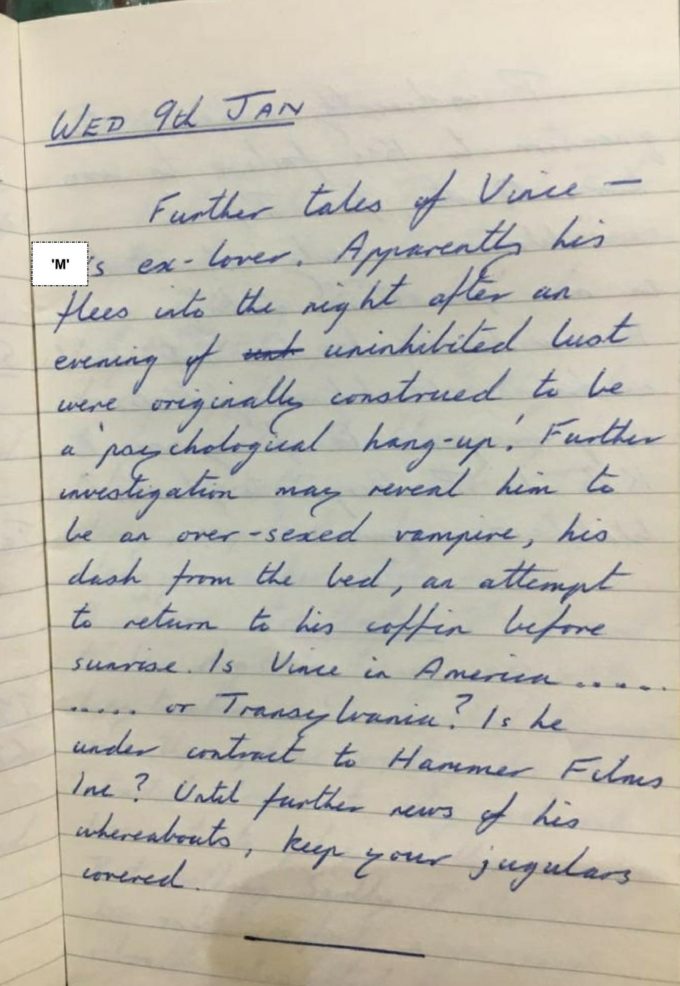

Pickford radically changed his appearance when undercover, growing his hair and a voluminous beard.

The family say that he would disappear for long periods of time, with no way of being contacted. No emergency contact details were provided to his wife, and no support was given during his absences.

IMPACT ON FAMILY LIFE

He parked his cover vehicle away from the family home, to which he returned during the evening and night – there would only be occasional contact prior to his arrival. This caused considerable disruption to the family routine, especially given his children were very young at the time. They feel they have made enough sacrifices as a family for his work, which he saw as protection of the country.

To avoid compromising his cover, there was no going to joint social gatherings or having friends round to their home. This left his wife extremely isolated while trying to raise her children, as she had no family in the UK and so was reliant for support on close friends.

Because socialising, even with fellow police officers, was minimal, she was effectively a single parent, socially vulnerable and alone. There was no support from Special Branch.

RELATIONSHIPS

While undercover, he began a relationship with another woman. This, along with the strains that had been put on the family (by the demands of his deployment), led to their divorce, within a year of Pickford leaving the field.

He went on to marry the other woman and have a child with her. This marriage also ended in divorce, some years later. She has not been traced, having remarried.

The Inquiry has confirmed that another, unnamed undercover officer has now provided an account of being tearfully told by Pickford that he had fallen in love with a woman associated with his targets and wanted to tell her the truth. This officer says that they offered to act as a conduit between him and the SDS managers [UCPI0000034307].

Pickford’s wife and children did meet this other woman, and the children joined them on holidays. They noted that she sometimes called him ‘Jimmy’. This indicates she had met him in his undercover identity.

The Inquiry has caused the family distress and anxiety, causing them to re-live unhappy times. This is exacerbated by needing to keep it from other family and friends. Having kept their obligations of confidentiality about Pickford’s work, they now feel betrayed at the thought of this information being released, especially as it led to the collapse of the marriage.

THE INQUIRY’S ACCOUNT OF REPORTS

Pickford’s time undercover has been set out by the Inquiry. He focused on anarchist and community groups in the Battersea/ Wandsworth area. He came across a number of other people who are now core participants at the Inquiry, including Dave Morris in 1976 [UCPI0000021496, UCPI0000017641].

He was particularly interested in Ernest Rodker, who he reported on throughout his deployment, providing many personal details including legal proceedings and birth of his son. It would appear that Rodker was the key focus of his deployment.

The early part of the deployment in 1975 focused on publications such as ‘Freedom’, ‘Lower Down’, ‘Up Against The Law’ and ‘Pavement’ [UCPI0000007125]. He also reported on small local left-leaning groups which held meetings and lobbied politicians – such as BPAG and BRAG (which Rodker was also active in).

ANARCHIST WORKERS ASSOCIATION

Having joined the Kingston branch of the Anarchist Workers Association (AWA), he helped set up the Wandsworth branch in July 1975 (later it became the South London AWA) [UCPI0000006950, UCPI0000012805].

He was elected treasurer of Wandsworth AWA in July 1975 [UCPI0000012685], remaining in that role until the end of his deployment.

He was highly active in the AWA, particularly at branch level where he was responsible for much of the local organising. This included arranging public events and writing articles for the AWA paper. He was the Wandsworth branch’s delegate to the Federation of London Anarchist Groups.

The Inquiry notes the high degree of activity, in comparison to the small numbers at the meetings, and asks whether it was it in fact him who essentially kept the Wandsworth branch functioning: would it have survived without him?

He also gave him access to the larger AWA network. He attended delegate conferences as well as AWA’s national conference.

The Inquiry notes that there are various reports from Pickford indicating his targets were alive to the possibility of police infiltration. There are also times when he cites some AWA members as having a willingness for violence to advance their aims, but it is all very rhetorical and about future revolutionary moments.

There is little in the reports to suggest any criminality or violence; the most tangible threat is a September 1975 report of some members thinking about disrupting a Royal Navy recruitment event with stink bombs and smoke pellets [UCPI0000007604].

Two local, community-oriented papers, ‘Pavement’ and ‘Lower Down’, are reported on. Even the collective members’ personal relationships and living arrangements are recorded [UCPI0000014967].

‘Up Against the Law’ (UPAL) was another publication, put out by a campaign group that assisted people trying to overturn wrongful criminal convictions.

It is believed – but unconfirmed – that Pickford acted as a distributor for the paper. He certainly reported on them – for example this November 1974 report details a dispute between UPAL and their printers [UCPI0000015096]. As with many Special Branch reports, it hard to imagine the relevance of this information to the police.

Like almost all undercovers from this period, Pickford also spied upon anti-fascist campaigners – in his case an umbrella group called Wandsworth Anti-Fascist and Anti-Racist Committee [UCPI0000021581].

‘Barry / Desmond Loader’ (HN13, 1975-78)

‘Barry / Desmond Loader‘ (HN13, 1975-78) was deployed into the Communist Party of England (Marxist-Leninist) from 1975 to 1978. He is deceased.

His widow confirmed in a very brief statement [MPS-0740967], that he stole his cover surname from a deceased child from Wiltshire, and that he had told her of the surname during his deployment.

The Inquiry says that Loader’s affiliation with the Communist Party of England (Marxist-Leninist) provided entry to several associated organisations, including the Communist Unity Association (Marxist-Leninist), the East London Peoples Front, the Progressive Cultural Association, and the Outer East London Anti-Fascist Anti-Racist Committee.

EARLY REPORTING

The first report held by the Inquiry believed to be attributable to Loader dates from February 1975. These include intelligence on the Marxist-Leninist Organisation of Britain [UCPI0000012145], the Free Desmond Trotter Campaign [UCPI0000007024], and the West London Campaign against Racism and Fascism [UCPI0000007632].

COMMUNIST PARTY OF ENGLAND (MARXIST-LENINIST)

Loader’s reporting from 1977 onward focuses largely on the Communist Party of England (Marxist-Leninist) (CPEM-L), in particular the East London Branch. Loader was also an active member of the Party’s cutural activities offshoot, the Progressive Cultural Association.

Like many of the undercover officers we have heard from in these hearings, Loader reported on people involved in actions against the National Front (NF), such as the organisation of demonstrations, pickets, and leafletting as well as a willingness to confront the NF directly.

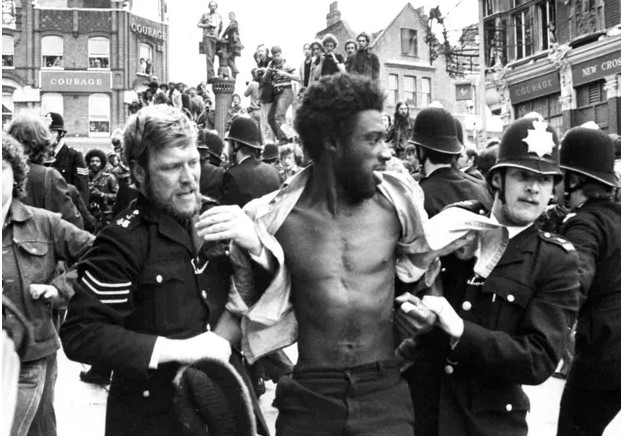

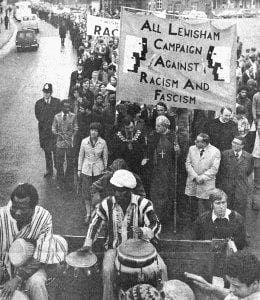

Loader attended the counter-NF demonstration that became known as the Battle of Lewisham on 13 August 1977. He was injured during the event, receiving a blow to the head – the first of the two times he was assaulted by uniformed police.

A report on a meeting of the CPEM-L in the aftermath of the Lewisham demonstration states that the Party were reviewing tactics to ‘attack’ the NF [UCPI0000011180]. Loader also notes in the same report:

‘it is generally agreed amongst members that, with the advent of the police shield, more sophisticated ‘weaponry’ is required in the riot situation.’

Internal Special Branch documents show that Loader met with Deputy Assistant Commissioner (‘A’ Ops) along with Peter Collins (HN303), DCI Pryde and DI Willingale following the Lewisham demonstration.

They wanted to convey his experience and provide recommendations for future policing in similar circumstances [MPS-0732885]. This meeting ultimately resulted in a note authored by DI Willingale aimed to assist with methods of policing future demonstrations [MPS-0732886].

ARRESTED TWICE & ‘BATTERED’ BY POLICE AGAIN

Loader was arrested twice while in his cover identity. The first occasion, in late 1977, was for ‘insulting or threatening behaviour’ following a clash with the NF outside Barking police station. Chief Inspector Craft of the SDS recorded that Loader was ‘somewhat battered by police prior to his arrest’ [MPS-0722618].

Seven other individuals from Loader’s group were also arrested. Superintendent Pryde maintained contact with a court official during the proceedings in April 1978. He informed them that one of the defendants was a police informant who they would be ‘anxious to safeguard from any prison sentence’ [MPS-0526784].

Ultimately, the charges against Loader were dismissed. Three of the other seven individuals were found guilty and fined on 12 April 1978 [UCPI0000011984].

These convictions were the subject of a 2014 report to the Crown Prosecution Service drafted as part of Operation Shay [MPS-0722618], examining miscarriages of justice stemming from undercover deployments.

Discussion in Special Branch Minute Sheets reveals that Loader’s senior officers prioritised keeping Loader’s identity secret over any other consideration.

SECOND ARREST

Just three days after his court appearance, Loader was arrested a second time during trouble at a National Front meeting held at Loughborough School, Brixton on 15 April 1978.

He was again charged with threatening behaviour under s.5 of the Public Order Act 1936, along with three others [UCPI0000011356].

At the hearing, an application was made to hear all the defendants’ cases together. However, the Magistrates decided to hear Loader’s case alone. This was, allegedly, because Loader had been involved in a separate incident to the other defendants, who had infiltrated an NF meeting while Loader stayed outside.

In fact, records reveal that Superintendent Pryde established contact with a court official during the proceedings and told them that one of the defendants was:

‘a valuable informant in the public order field whom we would wish to safeguard from a prison sentence should the occasion arise’.

Unlike the previous arrest, however, it is noted that Loader’s cover name was specifically given to the official [MPS-0526784].

All the defendants, in this case, were found guilty, with Loader being fined and given a one-year bind-over of £100. It is noted in the Minute Sheet that this sentence was considered ‘very useful’ as it would allow Loader to keep a low profile for the remainder of his deployment [MPS-0526784].

The Inquiry said that there is no evidence to suggest that this officer engaged in any sexual relationships in his cover identity.

A note made of a meeting with Commander Buchanan in 2013 suggests that Loader had difficulty reintegrating with the police following his deployment [MPS-0738057].

Loader is recalled by former CPEM-L party members with little detail, although they confirm he was known as ‘Barry’ rather than ‘Desmond’.

One member of the Party applied for Core Participant status at the Inquiry but was refused, despite obviously being in a good position to help the Inquiry with Loader’s evidence.

‘Geoff Wallace’ (HN296, 1975-78)

Summary of Evidence

‘Geoff Wallace’ (HN296, 1975-78) does not reside in the United Kingdom and the pandemic has prevented him from coming over, but he will eventually provide a witness statement.

To introduce him now, the Inquiry cites the account he gave to the Metropolitan Police risk assessor a couple of years ago. At the time he had not had access to the vintage reports attributed to him.

Wallace was a member of the Hammersmith branch of the International Socialists (IS) from summer 1975 to autumn 1978; IS became the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) during his deployment. He stole the identity of a dead child as the basis for his undercover persona.

SPYING ON SCHOOL CHILDREN

We heard earlier in the Inquiry that Paul Gray (HN126) spied upon a group called ‘School Kids Against Nazis’. Wallace also spied on school children.

The first report on the Hammersmith branch of IS signed by him [UCPI000009576] is dated 29 January 1976 and refers to students at Chiswick Comprehensive School’s intention to organise a Right to Work Campaign meeting for school leavers.

SPYING ON LAWYERS

In the course of the Right to Work Campaign, in April 1976 the IS magazine Socialist Worker hired solicitors to represent those arrested during the activities. Wallace reported [UCPI0000012323] on their complaints about police conduct, probably breaching legal privilege.

Wallace’s reporting contains many references to pickets and protests, some upcoming, some containing a list of those involved. In particular, he reports on a number of campaigns to protest the closure of local hospitals, such one [UCPI0000012378] on an April 1976 meeting of the Save Acton Hospital Campaign.

SPYING ON TRADE UNIONS

Wallace seems to be the undercover officer reporting in March 1977 [UCPI0000017818] on the Trade Union Committee Against Prevention of Terrorism Act. This was a Hammersmith group formed in April 1976 by local members of IS, the Troops Out Movement, Camden, Hackney and Hammersmith Trades Councils and various trades unions. Its aim was to provide a solicitor for anyone arrested under the Prevention of Terrorism Act which conferred emergency powers on police forces whenever terrorism was suspected.

According to a report from Wallace in April 1976 [UCPI0000012373] the Committee was suspected of having an underlying political goal; self-determination for the Irish people. In reality, they were actively campaigning for repeal of the Prevention of Terrorism Act by staffing pickets outside police stations holding people detained under the Act.

When the police raided the home of one of the activists in January 1978 [UCPI0000017917] they found a note amongst the seized paperwork that said: ‘In the event of no transport, phone Geoff Wallace’. Having a van available remained a key point in the tradecraft of generations of spycops afterwards.

YET ANOTHER TREASURER

Wallace held a series of positions of authority within his target group. The October 1976 report [UCPI0000021481] of a branch meeting of Hammersmith IS indicates that, as of 6 May 1976, Wallace was branch treasurer. Numerous other spycops of the era held the same post in groups they infiltrated.

By July 1976, it would appear Wallace had become the branch’s Socialist Worker newspaper organiser [UCPI0000017922].

SPYING ON ELECTION CANDIDATES

In a report on 5 August 1976 [UCPI0000011981] Wallace reported on a discussion at a meeting of the Hammersmith and Kensington branch of IS about standing in the Walsall by-election. In March 1978 the SWP talked about standing a candidate in the forthcoming general election in Hammersmith North. As these activities are within the parliamentary system, it is difficult to see how they fall under the counter-subversion remit of SDS.

NOTTING HILL CARNIVAL ‘RIOT’ 1976

The Notting Hill Carnival in August 1976 ended in a protest of young people of colour, harassed by an antagonising large police presence, and defending themselves against arbitrary police arrests. IS encouraged their members to join pickets outside the Magistrates Court where those arrested would appear. In September 1976 the branch also proposed [UCPI0000021361] that IS join the defence committee set up by the Black Liberation Front and Grass Roots and contribute to its funds.

YET MORE REPORTING ON ANTI-FASCIST ACTIVITY

In February 1976, the Coventry and Chrysler Right to Work Committee organised a march, supported by the IS, to counter-protest at a demonstration held by the National Front under the slogans ‘A Right to Work for Whites Only’ and ‘ Stop Immigration’.

According to the report [UCPI0000012230] that the Inquiry attributes to Wallace, after a peaceful march some IS members made their way to the location of the National Front election offices and attacked people with stones and bricks. At least one person was taken to the hospital.

Then, according to the same report, IS members then marched to a shopping precinct to chase away members of the National Party. This breakaway faction of the NF was led by fascist and Holocaust denier John Kingsley Read, who built a reputation for having said, after the murder of a young Sikh man in a racist attack, ‘One down, a million to go’. Read later joined the Conservative Party.

The Inquiry looks to this incident to perhaps justify this undercover deployment:

‘We note that, if the report is accurate, this was an occasion on which the violence was started by left-wing activists from the infiltrated group.’

This is not the first time that the Inquiry has used reports of ‘violent’ anti-fascist protests as a justification for many of the deployments.

ANTI-FASCISM IN BIRMINGHAM

Wallace may very well have have been one of the SDS deployed officers who attended a counter-protest march against the National Front in Birmingham. On 24 February 1977, London branches of the SWP and the IMG sent coachloads of their members to join the march.

An SDS report dated 7 March 1977 [UCPI0000017776] describes a single coach of SWP members being attacked by ‘five coaches’ of National Front supporters at Watford Gap Service station.

For some reason, the Inquiry glosses this incident in neutral terms:

‘The SWP contingent from NW London and West Middlesex districts appears to have been involved in an encounter with the National Front in a service station en route to Birmingham…’

This gives a misleading impression of this serious unprovoked attack by the NF on SWP members.

DS Richard Walker (HN368), representing the SDS management, was also dispatched to Birmingham by DI Geoffrey Craft (HN34) to ‘look after our interests’ as is remarked in a note in February 1977 [MPS-0730703].

BATTLE OF LEWISHAM & ANTI-JUBILEE PROTEST

A member of SWP who announced that he was mobilising local trades union branches to support an anti-Jubilee demonstration during the visit of HRH Princess Anne to Kensington Town Hall on 31 May, ended up in a report dated 26 May 1977 [UCPI0000017437].

Wallace also notes that of the 1,500 demonstrators expected, 1,000 were likely to be trade unionists who were ‘violently opposed’ to Jubilee celebrations, if such a thing were possible.

At the same meeting, branch members were urged to assist in staffing picket lines for the strike at the Grunwick photo processing factory. Again, in the Inquiry’s statement ‘intelligence’ on the Grunwick strike is offered as a supposed justification for the covert policing.

A report dated 21 July 1977 [UCPI0000011055] refers to the intention of the Hammersmith and Kensington SWP to send two mini-vans of people to an anti-fascist demonstration in Lewisham on 23 July 1977 ‘in order that the National Front could take a real ‘hammering’.

Celia Stubbs

Celia Stubbs

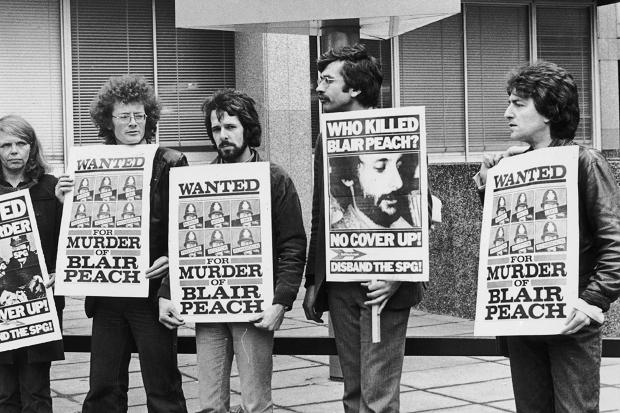

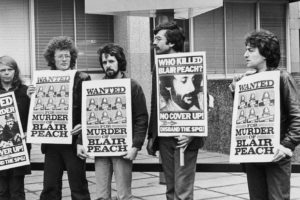

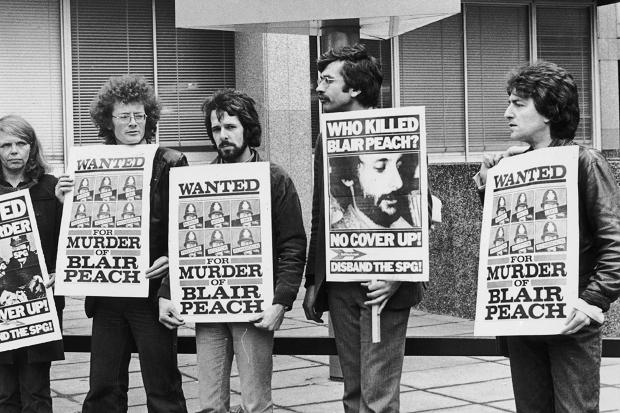

Celia Stubbs is a Core Participant at the Inquiry because of her relationship with Blair Peach and the campaign that followed his being killed by police in 1979, and the police cover-up that continues to this day.

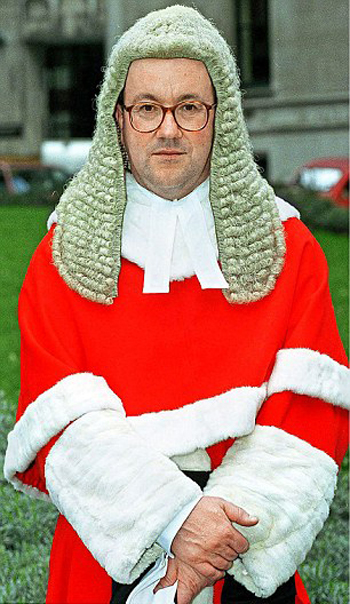

As Stubbs’ lawyer Matthew Ryder QC told the Inquiry two weeks ago, the killing of Blair Peach remains one of the most notorious events in British police history, a national disgrace, and a permanent stain on the Met.

Stubbs believes the spycops reported on her to prevent other police officers from facing justice.

MEETING BLAIR

Stubbs began by telling how she’d first met Peach in his native New Zealand around 1962 when she was there with her then-husband who was teaching there.

Peach visited London after she had separated from her husband, and they became a couple. They lived together from 1971 onwards. Peach took an active role as step-father to her two daughters

Stubbs has campaigned since Peach was killed, seeking greater police accountability and supporting miscarriage of justice cases, and other bereaved family campaigns. She was a founding member of Inquest, and involved in Hackney Community Defence Association.

POLITICAL BACKGROUND

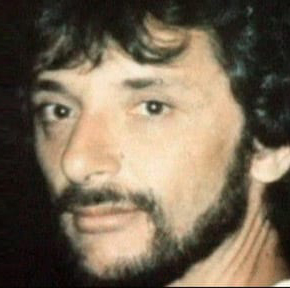

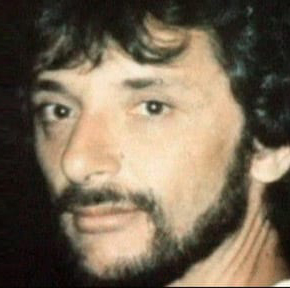

Blair Peach

In 1972, Stubbs joined the Hackney branch of International Socialists (IS), who later became the Socialist Workers Party. Peach joined later, around 1977.

She has recently learnt that Special Branch held ‘Registry Files‘ on both her and Peach – hers began in 1974/5, Peach’s in 1978 – but she hasn’t been shown any of the content of these. She feels that it would be useful to see these files.

Peach was a teacher, and ‘a very fervent trade unionist’ according to Stubbs, active in the National Union of Teachers in Tower Hamlets and Hackney.

IS put a lot of emphasis on building the class struggle, and Stubbs sold the ‘Socialist Worker’ newspaper in many places. She attended the group’s meetings, both public and private, as well as demonstrations and events supporting striking workers.

NATIONAL FRONT

One area of particular concern was a groundswell of far-right sentiment, especially the active presence on the streets of the National Front (NF). Stubbs and her comrades sold the Socialist Worker in the multicultural area of Brick Lane in East London, and regularly came into conflict with racist NF paper-sellers there. Peach and Stubbs joined the Anti Nazi League (ANL) when it was formed in 1977.

There was organised anti-fascist resistance to the NF, and usually a large police presence too. Stubbs recalled talking to people, lots of shouting at the fascists, banners and of course paper-selling.

The Inquiry showed a Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) report [UCPI0000010769] about the first public meeting of Hackney Community Relations Council, which took place at Stoke Newington Town Hall on 22 July 1976. It was attended by 250 people, significantly more than was normal for political meetings at the time.

The officer describes an NF member being ‘ejected from the assembly room amid a shower of fists and invective’, and that as people left they were taunted by NF members but did not physically confront them.

Asked if this was typical, Stubbs said she only remembered even that relatively low level of disturbance at one other meeting. She highlighted the fact that the anti-fascists had not risen to the goading of the fascists, adding:

‘I do remember unprovoked attacks and, you know, of course members of the left were often arrested. We certainly didn’t go out to do that, you know? We didn’t go to provoke’

The next report [UCPI0000021207] is from a meeting in a pub in North West London which took place on 24 April 1979, the day after Peach had been killed.

Persisting with the Inquiry’s habit of emphasising the violence of activists they read out the report’s summary of a speech made by SWP founder Tony Cliff.

Cliff is described as comparing the Southall anti-fascist demonstration with one two days earlier in Leicester, saying the vital difference was preparation, planning and organisation by the ANL. He is reported as saying ANL had provided Leicester stewards with maps of the area leading to:

‘a successful attack here on the police by about 200 demonstrators, high police injuries and a small number of arrests. On the other hand, at Southall, due to the lack of organisation and inadequate ANL stewarding, a lot of police had been injured, many demonstrators had been arrested and, more importantly, many demonstrators had been badly injured, with one death’

The bias of the reporting officer is apparent in the next paragraph which said:

‘many of the contributors from the floor then recounted their adventure during the demonstrations in Leicester and Southall and discussed instances of “extreme police brutality”.’

Stubbs said Tony Cliff was ‘absolutely wrong to compare Leicester and Southall’ or claim Southall just needed better organisation by the ANL in future. She explained that Southall was a very tight-knit community, ethnically diverse, a strong industrial base with factories around Heathrow, and well-organised, by the likes of the Indian Workers Association.

THE FATAL DAY

The NF’s meeting at Southall Town Hall on 23 April 1979 was part of their campaigning in the run-up to the general election two weeks later. Their candidate didn’t even live in Southall, but they were targeting constituencies with large Black and Asian populations.

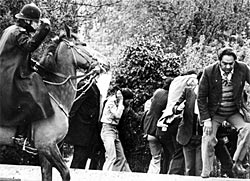

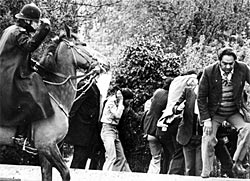

Mounted police intimidate protesters, Southall, 23 April 1979 [Pic: John Sturrock]

She told how the local community called for anti-racists from all over London to come to Southall to support them. She heard about it from her trade union. There wasn’t an IS branch in Southall at the time.

Stubbs and Peach travelled separately to the demo – he was on school holiday, whereas she came after work with some colleagues. She had never been there before.

When she arrived, Stubbs found it very crowded. She recounted finding herself near Southall Park where police were chasing people on horses, and on foot with truncheons, hitting people.

5,000 local residents had signed a petition against the NF being allowed to meet. Stubbs described factories shutting down in protest, and how it had started out as a large peaceful sit-down demonstration. But at 1.30pm, more than 3000 police moved in and it was ‘a town under siege’. Police shut all four of the roads that converged by the Town Hall, creating chaos, and started dragging protesters out.

Stubbs said:

‘it was almost as if the police punished the people of Southall… with the 700 people who were arrested, and then there were 348 people actually charged with offences.’

She made her way back to the station at about 7pm, and got the train back to Hackney without having seen Peach. She only learnt that he had been hurt later that evening when, at around 10pm, she received a phone call from a friend who was at Ealing Hospital.

SPYCOPS IN SOUTHALL

She knows that one of the spycops attended the demo in Southall that day. The Inquiry has taken evidence in secret from officers who it does not want to identify. It has then blended their testimony into a single ‘gisted’ document. In it, an officer says they were at the demonstration in Southall, saw violence and were horrified, and left before Peach was killed.

Stubbs is offended at this. Firstly, the total secrecy around the officer – we aren’t given their name, cover name, or any other details at all. Secondly, the idea that there was only one spycop at the demo is ridiculous.

Stubbs said it looks very much like the officer was distancing themselves as far as they could from the killing of Blair Peach. In this, it reminded her of the statements of the officers from the team responsible for his death, who said their van had actually stopped well away from Peach, that other police were present, and other things that were simply lies.

SPYCOPS AT THE FUNERAL

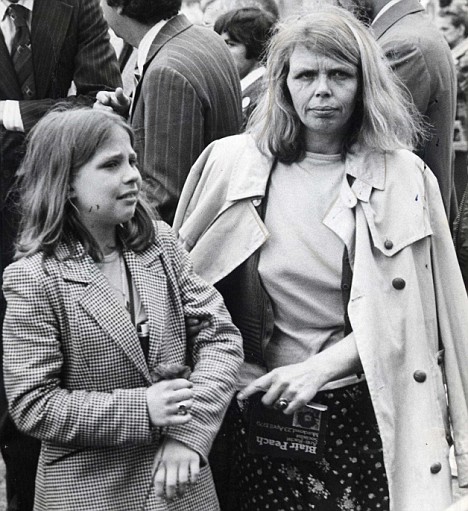

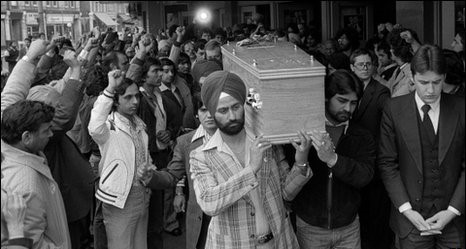

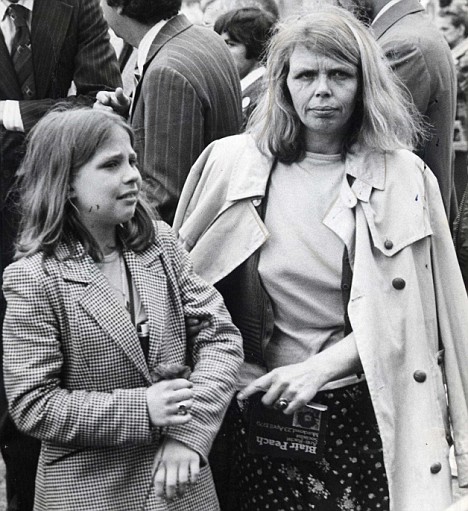

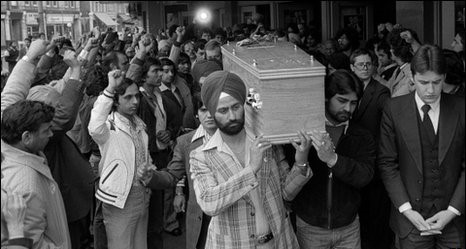

Blair Peach’s funeral, 13 June 1979

Blair Peach’s funeral was held on 13 June 1979. Members of Peach’s family came all the way from New Zealand for it, and 10,000 people came to pay their respects. Undercover police officers took photos of them for later identification.

Spycop ‘Barry Tompkins’ (HN106, 1979-83) says he attended the funeral in case there would be a risk of public disorder, something dismissed by Stubbs as ‘absolutely ludicrous’. 71 mourners are listed by name in Tompkins’ report.

The Inquiry showed several SDS reports [UCPI0000021218, UCPI0000021270] on meetings and protests that showed that the campaign for the truth about Peach’s death was a prominent topic among many sectors of the left at the time.

CAMPAIGNING FOR THE TRUTH

The Inquiry showed a report [UCPI0000021297] which included a leaflet produced by the Friends of Blair Peach. The report, seemingly unable to accept that the police were responsible for his death refers to injuries ‘it is alleged’ caused Peach’s death.

The SDS’ Annual Report for 1979 [MPS-0728963] outrageously suggests that it was the protesters’ fault that he died, saying that his death was the result:

‘of the virulent anti-fascist demonstrations.’

The campaign ideas on the leaflet are what one might expect: writing newspapers, phoning local radio stations, organising collections of money in workplaces, visiting MPs and circulating a petition to push for a public inquiry, putting forward motions at trade union branch meetings, encouraging affiliation to the ANL, and supporting calls for the Met’s notoriously violent Special Patrol Group, whose officers had killed Peach, to be disbanded.

These are traditional democratic campaigning practices, a long way from the SDS’ alleged remit of subversion and public order problems.

BURYING THE FACTS

The Met’s internal report, by Commander John Cass, found that it was ‘almost certain’ that a police officer from the Special Patrol Group killed Peach with a blow to the head.

A search of the officers’ lockers found numerous unauthorised weapons. One officer’s home had Nazi memorabilia and more unauthorised weapons. This information was leaked to the campaign and made public in June 1979.

Stubbs’ solicitor saw the weapons. One was a long cosh with metal at one end, which fits description of weapon that killed Peach.

The Cass report was published on 12 July 1979, then updated on 14 September, but it was not made public. Indeed, Stubbs had to wait more than 30 years before the Met would allow her to see it.

THE INQUEST

An October 1979 report [UCPI0000013435], detailed pickets being planned at Kilburn and Harlesden police stations, to coincide with door-to-door leafleting nearby on the eve of the opening of the first inquest into Peach’s death.

Stubbs explained that over 100 police stations were picketed in this way:

‘people were so angry about it.’

The coroner, John Burton, refused to sit with a jury. He also refused to allow the Cass report to be considered. Campaigners went for a judicial review, stopping the first inquest on that first day.

The Director of Public Prosecutions agreed that there was ‘no case to answer’ and so no police officer would be charged in relation to Peach’s death.

The inquest started again in April 1980, with a jury. The coroner, despite having seen the Cass report, did not accept that established version of events to be taken into account. The inquest concluded in May, the verdict: ‘death by misadventure’

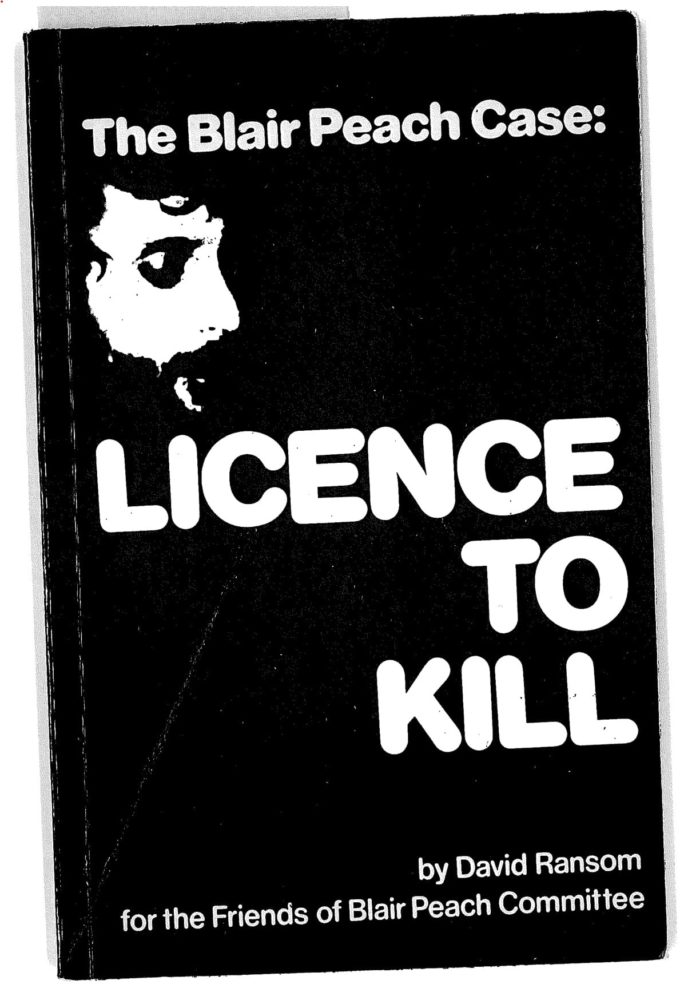

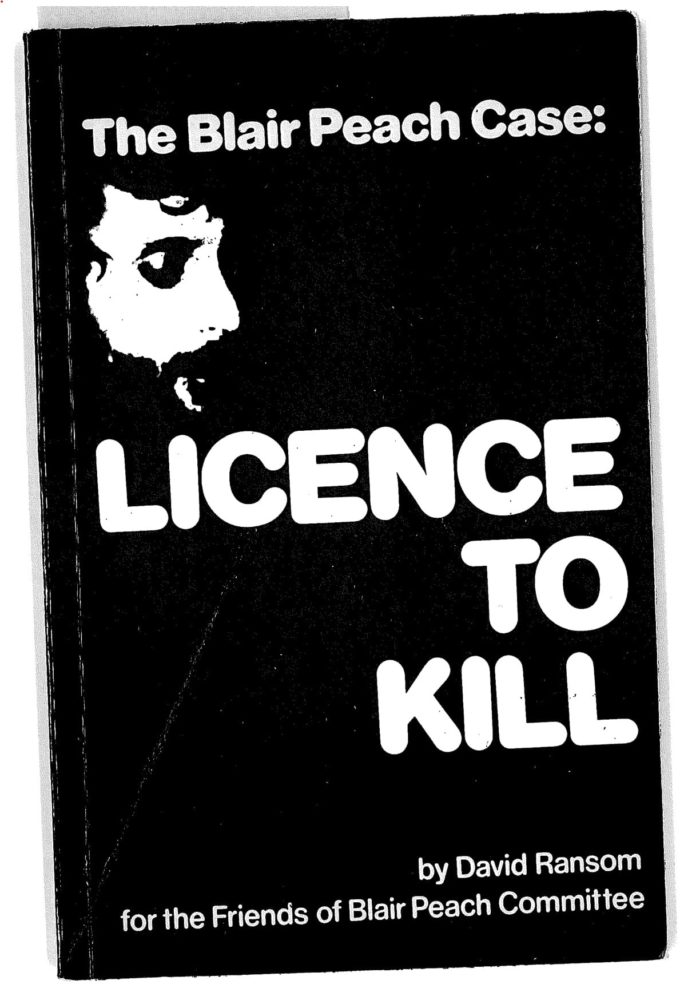

LICENSE TO KILL

One of Peach’s friends and teaching colleagues, David Ransom, wrote a booklet called License to Kill about the killing of Peach and the Special Patrol Group. The chapter on the Special Patrol Group (SPG) is being published by the Inquiry along with the Cass report [UCPI0000034077].

One of Peach’s friends and teaching colleagues, David Ransom, wrote a booklet called License to Kill about the killing of Peach and the Special Patrol Group. The chapter on the Special Patrol Group (SPG) is being published by the Inquiry along with the Cass report [UCPI0000034077].

License to Kill cited the Met’s attempts to defy the facts and portray the SPG as an elite, disciplined unit. They told the press that the SPG was the only specialist unit within the force and around 50% of applicants failed the vetting. Those who qualified did a ‘full tour’ of three years. The Met said it had no room for the ‘headstrong type or those who are liable to over-react to any difficult situation’.

This was all nonsense. The Met had a number of specialist units including, as we’re seeing, Special Branch and the SDS.

The purported ‘rigorous controls’ described by the Met had never existed at any time. At least seven of the officers who gave evidence to the Peach inquest had been in the SPG for longer than four years. One of them had been in the SPG for eight years, and two others had been part of the unit since it was founded, 14 years earlier. One of these was PC White, driver of the vehicle that delivered the killer to Peach.

SELF-INCRIMINATION

On 1 June 1980, the Sunday Times published an interview with the SPG’s Inspector Alan Murray. He is now widely believed to be the officer who killed Blair Peach.

Murray had just left the police and appeared to be trying to use the interview to cast his role, and that of his erstwhile unit, in a good light.

He spoke of how ‘the loony left’ were expected to behave in Southall that day, and that it promised to be ‘a tasty one’. He talked of the ‘elan’ (which Wilkinson said she took to mean ‘enthusiasm’) in the unit, and said they were proud to be known as ‘The Cowboys’. He recounted how they played the ‘Dambusters’ soundtrack as they arrived on duty.

‘When I was out with my unit I was my own boss to a large extent. Before acting I didn’t have to ring up and say “Guvnor, do you think this is right?” I followed my own experience to do what was expected.’

PC ‘Chalkie’ White, who had been suspended, was reinstated, not just as a police officer, but back into the SPG. Murray went on to become a lecturer in corporate social responsibility.

ANNIVERSARY COMMEMORATIONS

On the first anniversary of Peach’s death, SWP and ANL groups organised pickets at police stations all over London, as described in a report [UCPI0000020094] 18 April 1980.

Blue plaques on Southall Town Hall commemorating Gurdip Singh Chaggar & Blair Peach, 2019

Another report from the same day [UCPI0000013891] lists 16 police stations at which vigils were planned.

In 1981, on the second anniversary, public feeling was still high. A report [UCPI0000016434] mentions the South London Right to Work group’s plans to picket Eltham police station on the day.

The next report [MPS-0001219] was from decades later. It was written in the summer of 1998, regarding the plans to commemorate the 20th anniversary of Blair Peach’s killing on 23 April 1999.

The Inquiry wanted to avoid doubt and said that the line ‘Intelligence: Touchy Subject’ refers to the code-name used by the officer who filed the report, and is not some kind of comment on Stubbs or the Peach case.

Stubbs leapt at the opportunity to illuminate this topic. She told the Inquiry that the officer referred to was Mark Jenner (‘Mark Cassidy’ HN15, 1995-2000) who infiltrated the Hackney Community Defence Association and the Colin Roach Centre (also in Hackney). Whilst undercover he deceived an activist, ‘Alison‘, into a long-term relationship.

Cassidy reported that:

‘local trade unions are organising a large rally and demonstration, which will be presented with a strong anti-racist/anti-police flavour… the event will inevitably attract a large left wing presence with particular accent on anti-police type groups and the potential for disorder will be significant.’

Stubbs was indignant at this:

‘we’d had remembrance demonstrations after five years, after ten years, and this was twenty years. There’d never been any disorder. I don’t know why he put that. I think it’s pretty unpleasant.’

In 2019, for the 40th anniversary, a blue plaque for Peach was unveiled at Southall Town Hall, the Inquiry said. Stubbs added that there was also one for Gurdip Singh Chaggar, a teenager killed by white racists in Southall in 1976.

A year later, in June 2020, the plaques were stolen. It is not known if the culprits were supporters of the police, or of the National Front, or someone else.

BANDING TOGETHER

Returning to the aftermath of Peach’s death, the next report [UCPI0000014149] was from July 1980, concerning the formation of a new network of justice campaigns for cases of police brutality.

Stubbs was visibly emotional as she recounted the details of some of these, including:

- Jimmy Kelly, who had been severely beaten by Liverpool police on his way home from a pub in 1979 and taken into custody where he died within the hour.

- Richard Campbell, a 19 year old Black Rastafarian who was in Ashford prison, charged with breaking a shop window which he denied, who was force fed and died alone.

- Liddle Towers, a 39 year old electrician who died after being beaten in custody by eight officers in 1976. His first inquest ruled ‘justifiable homicide’. After campaigning, a second inquest ruled it was misadventure.

- Matthew O’Hara who was remanded to Pentonville prison for withholding his name at a hearing for rate arrears in March 1980. Though he had diabetes, the prison did not administer insulin. He was kicked in the stomach by a prison officer. After four days without insulin he was rushed to hospital and later died.

Stubbs explained that they wanted to get together with these other justice campaigns so they could support each other through the official processes such as inquests, as well as share information and push for reform of the inquest process. She does not see any valid reason to spy on these activities.

We were next shown a report from 1999 [MPS-0001707]. The Macpherson inquiry into the 1993 racist murder of teenager Stephen Lawrence Inquiry had been concluded in 1998, and plans were afoot to commemorate the 20th anniversary of Peach’s killing.

This report mentions many of the family justice campaigners who were active at this time, as well as the Lawrence family themselves.

As with Mark Cassidy’s report, the author feels compelled to make false claims about the likelihood of disorder:

‘Suresh GROVER, who is the organiser of this event, will positively contribute to ensuring that the day passes off without disorder. However, given the large number of groups and individuals who are likely to attend this march, the potential for disorder is high.’

MISSING OFFICERS, MISSING FILES, CONVENIENT AMNESIA

The Met’s own annual report of 1979 described the Southall protest as its ‘most significant event of the year’ yet we don’t see any spycops statement, apart from the single one summarised and blended into the gisted document.

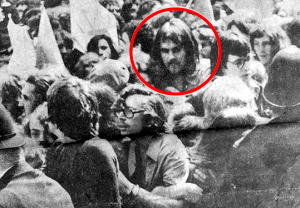

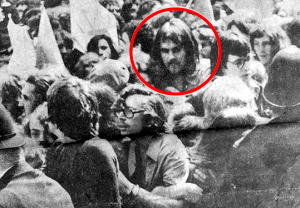

Kevin Gately in Red Lion Square, London, 15 June1974

Stubbs noted there were also scant spycops reports from the 1974 anti-fascist demonstration at Red Lion Square when protester Kevin Gately was killed. ‘Bob Stubbs’ (HN301, 1971-76) told the Inquiry he was at that demonstration but said he could not remember anything about it and only vaguely remembered Gately’s name.

Nothing from the SDS was presented to the public inquiry into the Red Lion Square protest. It’s simply not credible to say so few officers were involved and no significant reports were made.

Contrast these two anti-fascist protests – at which people were killed – with others in the same era where nobody died. Records show at least 18 undercover officers were present at the 1977 ‘Battle of Lewisham’ and we have more than 50 pages of reports.

It’s obvious that when someone is killed, the police don’t want to be associated with it. This looks like yet another cover-up. It makes us feel like we’re not being heard.

EAGER DENIAL

She wonders why spycop ‘Paul Gray’ (HN126, 1977-82) has been flagged up to her:

‘I was told that his statement was pertinent to my being spied upon. In fact, there’s absolutely nothing in his statement that involves me, except when, on 12 June 1979, he said he went with the SWP members of the branch he’d infiltrated to view Blair laid in state at the Dominion cinema in Southall.

‘He said he only went because it would have looked bad for him if he hadn’t and might have disturbed his undercover, but he then, immediately after that, said in his statement, “I never had anything to do with the family or Friends of Blair Peach”.

‘Why did he make that remark? It seems as though he quickly wanted to distance himself from. There must be something.’

Stubbs said that, having seen so many secret police reports, is left with as many questions as she had before.

‘I mean, Blair was killed by police officers and our feelings and campaigns were criminalised. The police, I think, wanted to keep ahead of our campaign so that Blair’s killers: we were never able to hold them to account.’

Speaking of how she and other Core Participants at the Inquiry feel violated, she concluded:

‘Core participants are fighting injustice in a climate where they are vilified by authority and we’ve been targeted. We don’t know why we’ve been targeted. I just hope this Inquiry, you know, will protect core participants, and that when you come to write your report, this will be foremost in your mind.’

The Inquiry’s Chair, Sir John Mitting, thanked her for her evidence, though it’s unclear how much weight he will give it.

Before the Undercover Policing Inquiry’s hearing on 23 April 2021, the 42nd anniversary of the killing of Blair Peach, there was a minute’s silence in his memory. In his introductory words, Mitting referred merely to Peach being killed by ‘a blow to the head’. He did not mention the police at all. It seems the Inquiry is unwilling to fully admit even the facts established by Commander Cass decades ago.

Full witness statement of Celia Stubbs

Stubbs recently spoke about Blair Peach, and spycops, to Channel 4 News.

<<Previous UCPI Daily Report (5 May 2021)<<

>>Next UCPI Daily Report (7 May 2021)>>

Tranche 1, Phase 1, Day 3

Tranche 1, Phase 1, Day 3

![Anti-racist protesters, Lewisham, 13 August 1977 [Pic: Syd Shelton]](http://campaignopposingpolicesurveillance.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Anti-racist-protesters-Lewisham-13-August-1977-300x195.jpg)

One of Peach’s friends and teaching colleagues, David Ransom, wrote a booklet called License to Kill about the killing of Peach and the Special Patrol Group. The chapter on the Special Patrol Group (SPG) is being published by the Inquiry along with the Cass report [

One of Peach’s friends and teaching colleagues, David Ransom, wrote a booklet called License to Kill about the killing of Peach and the Special Patrol Group. The chapter on the Special Patrol Group (SPG) is being published by the Inquiry along with the Cass report [

He says he recalls Jill Mosdell (

He says he recalls Jill Mosdell (

He described his weekly routine. The groups he was infiltrating would often meet/ be active until late at night, so Sloan would sometime sleep at their homes, rather than at his bedsit.

He described his weekly routine. The groups he was infiltrating would often meet/ be active until late at night, so Sloan would sometime sleep at their homes, rather than at his bedsit.