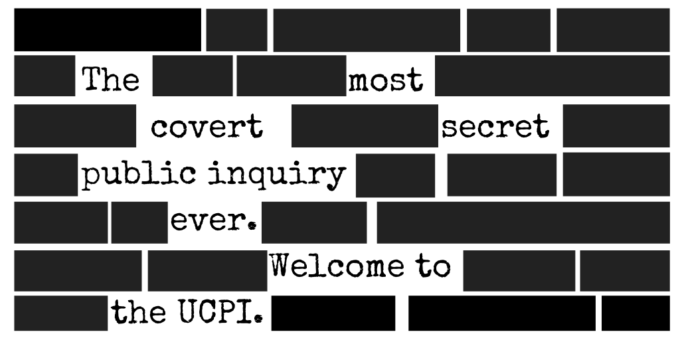

UCPI – Weekly Report 7: 10-13 May 2021

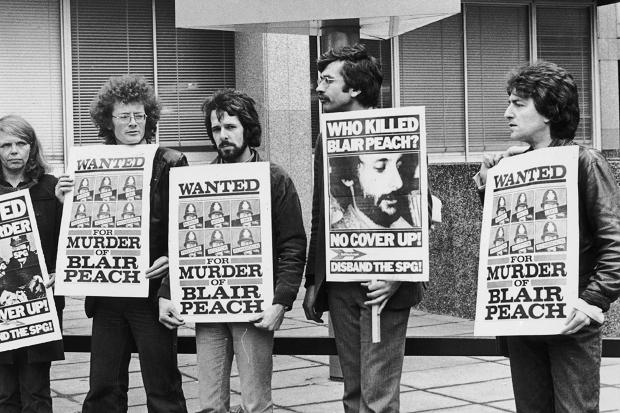

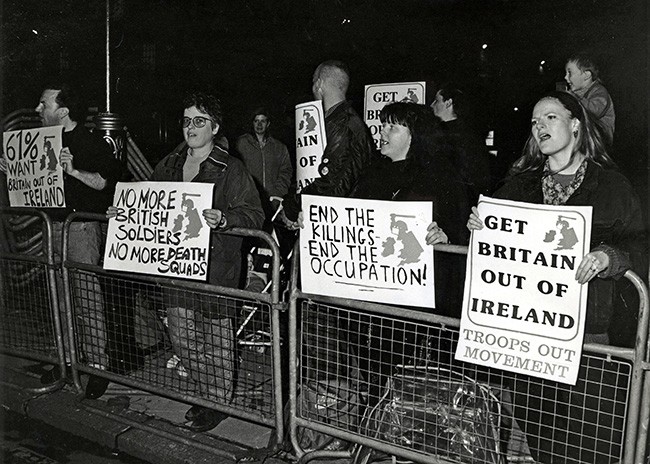

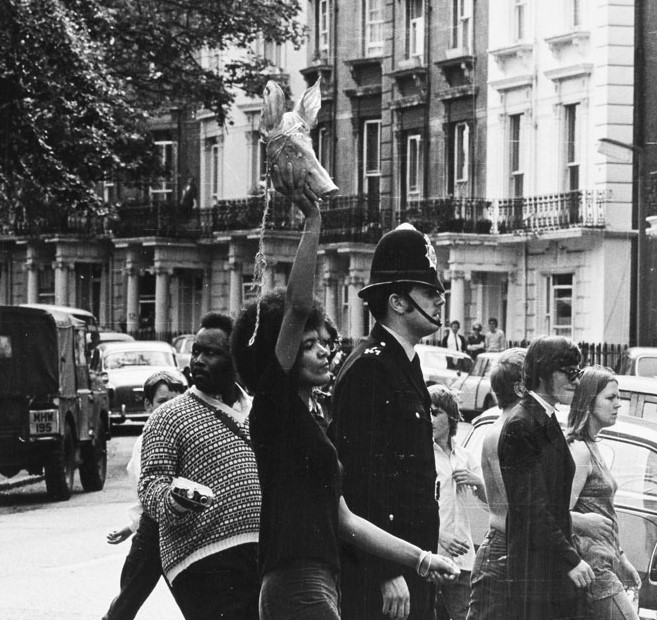

Blair Peach protest, 1979

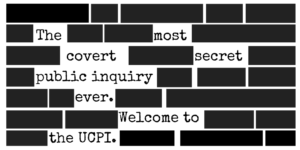

This summary covers the final week of the four-week 2021 hearings of the Undercover Policing Inquiry (UCPI), examining the activities of the Metropolitan Police’s secret political unit, the Special Demonstration Squad, from 1973-82.

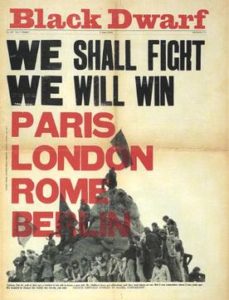

The UCPI is an independent, judge-led inquiry into undercover policing in England and Wales. Its main focus is the activity of two units who deployed long-term undercover officers into a variety of political groups; the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS, 1968-2008) and the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU, 1999-2011). Spycops from these units lived as activists for years at a time, spying on more than 1,000 groups.

THE DECEIVED AND THE DECEIVER

The UCPI hearings on 10 May and 11 May were notable for the consecutive appearances of an activist who had been deceived into a sexual relationship with an undercover officer, and the actual spycop who had deceived her.

‘Madeleine’ was the only activist we heard from this week. State core participants giving evidence were spycops ‘Vince Miller’ (HN354, 1976-1979), ‘Paul Gray’ (HN126, 1977-82), and ‘Michael James‘ (HN96, 1978-83). Summaries of evidence were given for three other spycops, and documents introduced for a fourth, who is now dead.

Owing to the refusal of the Inquiry to release names or photographs of officers, there are many people who may never know if they were spied on. The Inquiry has also refused to call as many spycops as possible to give evidence, so we are unlikely to ever have an accurate picture of their activities.

CONFLICTING ACCOUNTS

Once again, everything we heard this week supported the emerging picture that we do have. People who were spied on gave clear, consistent, and detailed accounts of their actions, including the moral and ethical standpoints that led them to join the groups that were infiltrated.

Spycops gave conflicting accounts of what they did; whether they had intimate relationships with activists, what went on in safe-houses, what their managers were or were not aware of, and even whether or not their work was useful. They contradict each other, and sometimes contradict themselves, whether in different reports or even within the same session of giving evidence.

This was very clearly shown this week when comparing the evidence of undercover ‘Vince Miller’ (HN354, 1976-1979) who infiltrated the Socialist Workers Party (SWP), and ‘Madeleine’, an SWP member who he deceived into a relationship. Madeleine gave evidence on 10 May, Miller on 11 May. Both took a whole day.

Miller was the first unmarried officer to be deployed by the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS). He was in a relationship, however, and this was one of the first things his superiors asked him about.

He believes this was because being married was preferred, as having a wife meant some form of support whilst enduring the stress of an undercover deployment. All the other evidence from spycops this week (and beyond) echoes this statement: family ties would prevent them ‘going rogue’.

‘Paul Gray’ (HN126, 1977-1980), giving evidence on May 13, said he thought ‘you had to be married’ to join the squad, as:

‘It led to a secure background, a secure home… I suppose it was good to have somebody at home when you came back after a long weekend or a long day’

It appears that, despite this being a deliberate choice by the SDS, no thought was given to the impact it had on the officers’ wives. Contact phone numbers for their husbands were not given until 1978, when one wife asked for this.

Wives were expected to do everything to help their husbands, up to and including moving house at short notice if their cover was blown. Many of them were left acting as single parents for weeks at a time. They believed their husbands were doing work crucial to the security of the nation.

UNMENTIONED ONE-NIGHT STANDS

Madeleine is one of four women who Miller has admitted to having intimate sexual contact with. Two of the others were not activists, nor were they connected with his target group. He says he simply met them in the pub – whilst undercover and claiming expenses – and had what he describes as ‘one-night stands’ with them. This was very early on in his deployment, when he was still exploring the area he had to infiltrate.

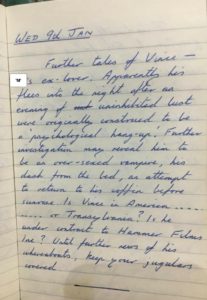

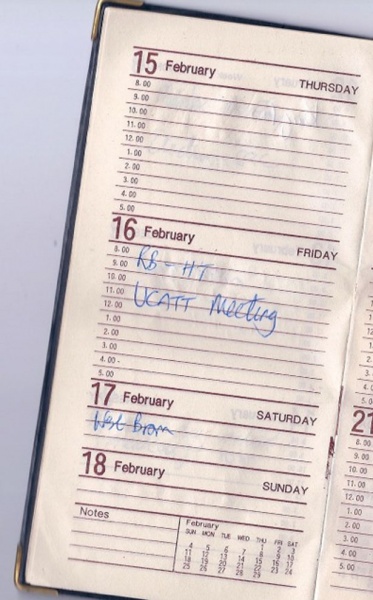

Madeleine’s relationship with Miller described in a friend’s diary, January 1980

Since they were nothing to do with his deployment, Miller chose not to mention them in his ‘impact statement’ to the Inquiry. Even when his solicitor was sent a letter by the Inquiry specifically asking for details of all sexual relationships, Miller remained silent. It was not until a year later – in his witness statement – that he admitted to them.

This alone is enough to bring his overall credibility into question. Everything he says must now be examined through a lens of ‘is this the whole story?’ What would it serve Miller to omit from his evidence?

David Barr QC, Counsel to the Inquiry, seemed to be aware of this as he questioned Miller. Barr kept the pressure on to an extent that made Miller literally sweat, as he contradicted himself repeatedly about matters of procedure and events in the SDS safe house. When questioned about his deception of Madeleine, Miller flushed red and was visibly deeply uncomfortable for the duration of that topic.

On the previous day, Madeleine herself was open and quietly compelling. Miller claims that he only had sex with her once, but she gave the Inquiry a detailed account of their months-long relationship. This is backed up by near-contemporaneous diaries detailing conversations about Miller’s refusal to stay the night after he’d had sex with her.

MANIPULATING PEOPLE BY LYING

Miller told Madeleine his refusal to stay over was psychological, that he didn’t feel safe unless he woke up in his own bed. He also told her he had grown up in a children’s home, and recently had a bad breakup from a toxic relationship. Giving evidence, Miller said it hadn’t occurred to him that his cover story of past pain and not wanting to be hurt again might evoke feelings of sympathy, intimacy and protectiveness.

This is astonishing, given that his entire job consisted of manipulating people by lying to them. Like all the spycops we’ve heard from so far, he says he received little training. However, the ability to gauge people’s reactions to what you tell them is surely a prerequisite for working undercover. For example, Miller was once asked what he was doing for Christmas. To end the topic, he replied that both his parents were dead.

His cynical tale of woe is another piece of spycop tradecraft, one that other women deceived by spycops will recognise all too readily.

‘REALLY, REALLY SINISTER’

Barricade on Cable Street, 4 October 1936 [Pic: Bishopsgate Institute]

Madeleine was about 15 when she joined the International Socialists (IS), which later became the Socialist Workers Party (SWP). In 1970, when she was 16, a Special Branch Registry File on her was opened.

Parts of that file are redacted by the Inquiry, which she finds ‘really, really sinister’; what 50-year-old information about her does the Inquiry not want her to see?

AUTOMATIC TARGETS

Miller explained that it was not unusual for 15- and 16-year-olds to be spied on and have files, if they were ‘sufficiently active’. Additionally, it streamlined the paperwork to open a file on someone if they were ‘constantly being referred to in all sorts of practices’.

The inference is that if children were often mentioned in reports on their parents, it was easier for the SDS administration to open a file on them. This is backed up by the evidence of ‘Michael James‘ (HN96, 1978-83).

In a self-fulfilling manoeuvre, children and adults became automatic targets for the State simply because they had a file.

Madeleine had split up with her abusive husband in the autumn of 1978. By this time, she had known Miller as a member of the SWP for over a year. A flatmate’s diaries show he visited their flat in summer 1977. After the breakup, she increasingly regarded him as a friend.

This was the period during which Miller was infiltrating the Walthamstow branch of the SWP. He became treasurer, then district treasurer and social committee organiser for the Outer East London District Branch. Miller organised fund-raising gigs and other social events. As people dedicated to the same ideals, the SWP members’ lives were very enmeshed.

PUBLIC DISORDER PICNIC

The Queen’s Silver Jubilee in June 1977 saw one such social event. It had been declared a one-off bank holiday; in a gentle push-back against the imperial overtones of the occasion, Walthamstow SWP organised an anti-Jubilee family picnic in Epping Forest.

The Inquiry asked if the picnic was likely to involve any public disorder:

‘Absolutely not, no. It was just a picnic. With children, I might add.’

Given some of the things we are expected to believe from other State witness statements this week, the Inquiry not knowing what a picnic involves is the very least of it.

The direct actions of the Walthamstow SWP were not geared towards public disorder either. A report mentions them ‘occupying’ a Sainsbury’s supermarket, but this is untrue:

‘what they probably did was stand outside with banners, handing out leaflets and talking to shoppers… We felt supermarket prices were kept artificially high to extract profit for shareholders.’

It is hard to see why campaigning for lower prices at Sainsbury’s would be a threat to democracy. This explains why the spycops exaggerated in their report, something that happened throughout this period.

There is a paradox here. On the one hand, the undercovers talk about ‘hoovering up’ information indiscriminately for superiors to make use of, never filtering or questioning the value of the intelligence. On the other, the threat factor of small, peaceful groups is repeatedly made out to be far greater than it was.

On the third – because you need three hands to keep track of their contradictions – they describe the groups as harmless, then circle back round to the justification of information possibly being useful in the future. Or being ‘filed and never used again’, according to ‘Michael James‘ (HN96, 1978-83).

STEALING THE IDENTITY OF A DEAD CHILD…

James infiltrated the Socialist Workers Party and Troops Out Movement, occupying a senior role in the latter by the early 1980s. Like most of the spycops from this period, he was given precise instructions to steal the identity of a dead child and had no qualms about this:

‘I had no moral reservations about this at all… And I couldn’t see why it was a moral issue, because it didn’t involve anybody.’

Pressed on why he thought this:

‘No family were injured or caused any distress because of this practice.’

Later, when queried by the Inquiry Chair, Sir John Mitting, he added:

‘I dismiss what I see in the press about what they say about the stress given to families whose children have been used in the way. I don’t accept that. From my own knowledge that didn’t happen.’

‘Paul Gray’ (HN126, 1977-82) said in his written statement that it was the founder of the SDS, Conrad Dixon, who had instigated the use of dead children’s identities. Giving evidence on 13 May, he changed this to say that the practice was inspired by the film The Day of the Jackal.

When pressed by the Inquiry as to which it was, Gray decided on the latter as he had:

‘checked Wikipedia and the film had just come out when we started doing it.’

He was not alone among the spycops in having a cavalier attitude to the truth, but he was particularly blatant about how much being asked about it annoyed him. He often gave obtuse answers to straight-forward questions, and at times refused to answer them outright, despite having sworn to tell ‘the whole truth’ before giving evidence.

Interestingly enough, he took offence at what was said in what is presented as his own written witness statement:

‘I have not written that, not at all, this is not my kind of English. This was written for me.’

His words and attitude confirm something previously suspected – that the statements were worded for the spycops, not by them.

…TO SPY ON LIVING CHILDREN

Returning to Michael James, a May 1979 report he wrote [UCPI0000021293] gives personal details about a member of Clapton SWP and Hackney Women’s Voice. It describes her as divorced, with a six-year-old child. Why report on her marital state, the age of the child or even that she had a child?

‘All I can conclude is that I was trying to paint a picture of an individual that may have been used in the future.’

Would you have been concerned at all about reporting information on children?

‘Well, all I said was she had a daughter of six years. I mean, I’ve not gone into any more detail.’

In August 1979 he reported [UCPI0000013300] on an under-18-year-old SWP member, including the school they went to. He said he wasn’t concerned about having done this.

James gave evidence on 13 May, a long and somewhat torturous process that saw him evading giving answers and instead suggesting questions he thought should be asked. This left Inquiry counsel Steven Gray QC persistently cutting through James’ repeated shambling around answers, for which he is to be applauded.

The Inquiry discussed other examples of intrusive reporting. When pressed to justify various egregious sections in his files, James fell back on the defence that it didn’t really matter. It was just information that mostly went nowhere, kept on the off-chance it might actually be useful one day; but since that was in the future, who knew, so you reported everything.

INTRUSIVE REPORTING

Despite James’ claims that the information would, in his experience, ‘never see the light of day’, many of his reports were passed to the Security Service (MI5). All the files published by the Inquiry with a reference number beginning ‘UCPI000…’ are taken from the Security Service’s existing records.

As Steven Gray QC pointed out:

‘the fact that it wasn’t going to see the light of day again in your experience is not borne out by the fact that we’re looking at it now, is it?’

The theory that the reports would not be looked at until some time in the future could also explain the fictional tendencies of the spycops who wrote them. A practice familiar from SDS reports seen earlier in the hearings was to take the most extreme statement anyone made at a meeting and portray it as the whole group’s real basis. Realistically, most meetings, from business to Brownies, would suffer under that parameter.

A January 1979 report [UCPI0000013063] from Miller also mentions children. School Kids Against the Nazis (SKAN) had been formed when the National Front held a demo outside a school in multicultural East London. About 200 pupils had opposed it, with 15 arrests – all but one of them Black kids.

SCHOOL KIDS AGAINST NAZIS

‘Paul Gray’ (HN126, 1977-1980) also reported on SKAN, and seemed preoccupied with one Black boy in particular. Gray reported on his family life, that he spoke at a SKAN meeting, and leafletted schools in a campaign against education cuts, among other things.

‘Paul Gray’ (HN126, 1977-1980) also reported on SKAN, and seemed preoccupied with one Black boy in particular. Gray reported on his family life, that he spoke at a SKAN meeting, and leafletted schools in a campaign against education cuts, among other things.

Gray claimed this reporting was justifiable from a public order point of view, but then denied that the reports were his [UCPI0000011997], [UCPI0000011380].

Shown a report detailing minor criminal offending of a minor schoolboy, [UCPI0000011994], he was asked if this was the sort of information he would have reported on SKAN?

‘Although SKAN’s members were young, they were just as violent as any other anti-fascist group.’

The Inquiry then showed a short video of SKAN Hackney – an endearing bit of footage with schoolkids, black and white, explaining they were friends and colour did not play a role, and that they were against the NF stirring up tension.

Gray agreed that this was the impression that he had of SKAN at the time, but claimed:

‘the characters that I was aware of were a lot more violent.’

Asked specifically about the child prominently featured in his reports, Gray conceded he had never seen him committing violence at demonstrations, but ‘he was always the first out of the bus at Brick Lane’. It is also notable that he described the boy as having an ‘effeminate manner’. He says he never thought about whether this was appropriate or not.

SUGGESTIONS OF INSURRECTION

Gray said that in fact, the legitimacy of reporting on SKAN at all was never discussed with him by superiors. It was not talked about at the weekly meetings. Nor was the reporting on girls protesting because they were not allowed to wear trousers to school [UCPI0000021267].

Returning to the 1979 report from Miller, this said SKAN:

‘can, with short notice, get large numbers of school students on to the streets, should the need arise.’

The Inquiry asked Madeleine if SKAN were indeed able to suddenly create a mob ready for street violence. Yet again, she had to deflate suggestions of insurrection. SKAN was a self-organising group of kids responding to the upsurge of racism around them:

‘The idea that we would have somehow had to have planted these ideas in their heads is a bit ludicrous really. It was their own experience.’

Madeleine notes other reports are deliberately facetious, and often selectively quote a few individuals’ opinions rather than the general view, even just picking up on comments made by members of the public. She elegantly described it:

‘There’s a little bit of embroidery going on in many of the reports. There would have been people there who would have expressed opinions that we wouldn’t necessarily agree with, but we would discuss and debate and argue with them.’

MADELEINE BELIEVED HERSELF SAFE

In the summer of 1979, Madeleine was 25 and slowly coming out of her shell after years of her husband’s possessive behaviour and abuse. At a house party in Ilford, mainly attended by SWP members, she was happy when her SWP comrade of three years, Vince Miller, pulled her into his lap, and when he later put his arms around her. She was not looking for a relationship, but believed herself safe with him:

‘I thought he was lovely. A really nice guy. I thought he was a genuine, lovely, easy going person, I thought he was sensitive, he had this story of heartbreak and all the rest of it. I felt he was looking for genuine relationships with people.’

After the party, he took her back to her flat and they began a sexual relationship. It was the only time that he stayed the entire night with her, leaving in the morning.

ABSOLUTE BETRAYAL

Asked how she would have felt to discover Miller’s true identity at the time, she said it would have been devastating. She was young and naïve, and would have been profoundly shocked and distraught:

‘I’d made myself very vulnerable to him and I trusted him, and to me it would have been an absolute betrayal… I would have regarded it, as I do regard it now, as rape.’

Miller claims Madeleine invited him up to her room. Questioning Miller, David Barr QC bluntly asked if he went because he wanted sex – despite the fact that he was a serving police officer on duty?

‘I think I’d have to say yes.’

Asked if he thought Madeleine would have had sex with him if she knew who he really was, Miller admitted:

‘if she knew that I was a police officer then almost certainly not… But I’m both a police officer and a person, so she might have seen the person, not the police officer.’

Had she seen the person, she would have also seen that he was in a committed relationship. What she saw instead was a single comrade she’d known for years, who had become a trusted friend, and then lover.

The Inquiry attempted to downplay the impact the relationship would have had if Madeleine hadn’t latterly found out the truth about spycops. This gives no consideration to the reality of the situation as she experienced it at the time.

THE FOCUS OF HER AFFECTIONS

Madeleine hoped that they would become a couple. She didn’t see anyone else, and her feelings for him grew. They met about once a week; always at her house, never his. She was very keen for the relationship to continue, as she was ‘never looking for a one-night stand or casual sex with anyone’, and ‘he seemed very keen on me’.

Their regular dates continued for a couple of months. He was, she says, the focus of her affections. However, towards the end, things changed:

‘He became increasingly distant, and I began to become disappointed that it didn’t seem to be going the way I wanted it to go. And, yeah, I kind of became a bit upset about it.’

Madeleine found herself wondering if it was her fault that Miller was withdrawing his affection. The last time she saw him was at a friend’s house. She hadn’t seen him for about a week. He was sitting on the other side of the room with a woman, and she sensed from their body language that there was something between the two of them. Madeleine now thinks this is the other SWP member that he has admitted deceiving into a relationship.

FEIGNING EMOTIONAL DISTRESS

Miller ignored Madeleine. When he left, she followed him to ask why he was being so distant. He said that he’d already told her that he couldn’t get too involved and that he didn’t want to get hurt again.

She remembers his departure damaging her self-esteem, leaving her feeling upset, disappointed and rejected. She saw it as part of a pattern with her marriage and thought:

‘God, have I made another mistake?’

He said he was going to go to California to ‘find himself’. This is yet another early example of what became standard practice – spycops would cover the end of their deployment by feigning emotional distress and say they were going abroad to sort themselves out.

The emotional turmoil created by some of the later officers had huge impacts on those who loved them. More than one desperate woman deceived into a relationship went searching in the country where her partner was supposedly living, not knowing he was actually back at a desk job in Scotland Yard.

FURTHER TALES OF VINCE

This was not a relationship that had ‘very little impact’, and it was caused by the spycops whether Madeleine knew of them or not. The revelation that the man she knew never really existed has caused more recent impact, undoing the peace that Madeleine eventually made with the end of the relationship.

‘To discover that I didn’t know him at all and that he was a fiction, that’s been quite difficult to get my head around. He doesn’t actually exist, it was all an act, wearing a mask… it’s really chilling and sinister… I just don’t know how people can behave like that.’

It is indeed abhorrent that Miller chose to have sex with a young woman who had no idea of his true identity, and who he knew was emotionally vulnerable. Perhaps even more so that he claims it didn’t cross his mind that she might feel pressured, after being in a relationship with a controlling man.

When asked by the Inquiry about pregnancy concerns, Miller put all the responsibility on Madeleine:

Q. Did you use contraception?

A. Not that I recall.

Q. Did you give any thought to the consequences of fathering a child when you were in fact an undercover police officer?

A. No, I didn’t. I think my perception was that as a full feminist socialist supporter, then if there was any need for protection, then she would have mentioned it. I didn’t see her as some kind of shrinking violet, or something like that. This was a member of the women’s movement, and women had the same right to ask for things and to insist on things as a man. And I would have supported that then. I incidentally still do. So she would have had the right – absolute right to insist, if it was necessary.

Q. But in the absence of any insistence?

A. Then I assumed everything was safe. In contraceptive terms.

Miller’s account of their relationship differs so wildly from Madeleine’s that even the Inquiry Chair, Sir John Mitting, butted in to question him on it.

AN ESSENTIALLY TRUTHFUL PERSON

Miller repeatedly stated that he had little or no memory of many events during this time. Madeleine has clear recollections of the last time she saw him. Miller said he has no memory of saying goodbye to her before he ended his deployment. However, he maintains that he only had sex with her once, which he now describes as:

‘inappropriate and unprofessional.’

Mitting stressed that Madeleine had impressed him when giving evidence:

‘As a sincere and essentially truthful person, trying to tell me, as best as she could remember, what happened between you and her.’

Their relationship was not the only topic where Miller delivered a different version of the truth.

August 1977 saw a key moment in the fight against fascism in Britain. The National Front (NF) were organising a march in Lewisham, and there was a huge counter-demonstration. The collision of the two became known as the ‘Battle of Lewisham‘.

Miller says Walthamstow SWP members checked out the route the night before, and deposited piles of bricks that could be used as weapons the next day. He also claimed they were armed during the march.

Madeleine utterly denies all of this. There is no evidence that anybody ever planted any bricks at all.

BATTLE OF LEWISHAM

This confrontation is now commemorated with a plaque in Lewisham. It was the turning point in the rise of the right wing, and the beginning of the end of the NF.

Miller remembers that everyone who opposed the NF agreed that the far-right had to be stopped from marching through New Cross, a very multicultural area, and that they all organised and planned to stop it.

Miller was an SWP steward for the march. He described the NF as ‘deliberately confrontational’, adding:

‘I don’t think these situations would be allowed to take place now.’

Despite the Met deploying 4,000 uniformed officers, Miller explained that ‘following the march’ was impossible; ‘it was chaos’. The police had no protective gear in those days. In his words:

‘the mounted branch took a complete hammering.’

There were running confrontations all over the area for the rest of the day. Miller described how, after the march was over, members of the far-right were poised to attack the protestors.

Battle of Lewisham plaque, erected on the corner of New Cross Road & Clifton Rise in 2017

Miller said he was ‘too close for my own comfort’ to the confrontations, but that he avoided getting involved in any ‘direct physical violence’ himself.

He remembers phoning up other spycops after the event, to check they had got home safely. A number of them were present that day, because they were infiltrating many of the other groups who attended, not just the SWP. They definitely discussed the event in the safe-house, he confirmed.

We learned from a report dated 23 August 1977 [MPS-0733369] that Special Branch held a debriefing for eighteen of its officers who were present. Miller says he was not one of them, and explained that other Special Branch plain clothes officers would have gone to the march, and that it’s likely that the SDS’s views would have been represented at the meeting by one or two officers, ‘at a high level’.

He notes the SDS undercovers were disappointed that their pre-intelligence had been ignored, resulting in severe violence. Despite that, in the SDS Annual Report for 1977, the Lewisham event is described as a triumph for the unit.

THE DEATH OF BLAIR PEACH

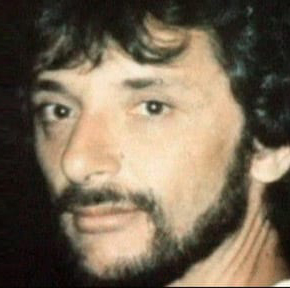

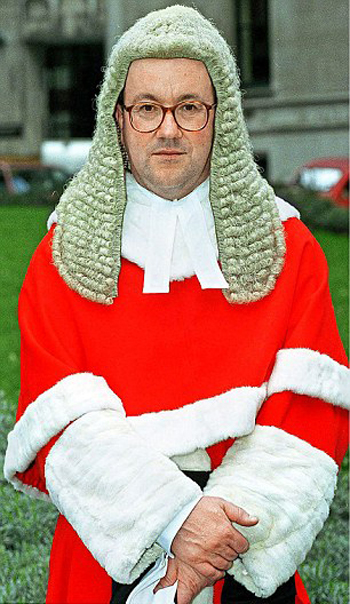

Blair Peach

By way of contrast, we have been told that only one spycop was present at the April 1979 anti-fascist demonstration in Southall where police killed Blair Peach, and he left early because it had turned violent.

The anti-fascist protest was a reaction to a General Election rally held by the National Front in a very multi-cultural area of London. This deliberate baiting by fascists was exactly the kind of event that the SDS should have been reporting on.

Gray said his branch made arrangements for the demo, [UCPI0000021193], but he did not attend, saying he probably had an SDS office meeting if it was on a Monday (which it was not) or had to go to work in his cover deployment (despite stating earlier that he never did any work there).

OBVIOUS LIES

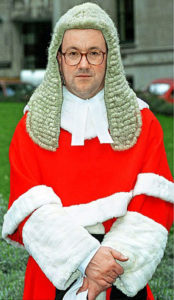

Celia Stubbs, 2021

Gray claimed that he did not hear about what had happened to Blair Peach, apart from what was on the news. Like many of his colleagues, he claims there was never any discussion about it at meetings of the SDS.

This is an obvious lie, not just because it was a fairly significant public order event, but because it was, naturally, discussed at his SWP branch [UCPI0000021218].

Gray also denied knowing Blair Peach’s partner Celia Stubbs (who gave evidence on 6 May 2021), despite having reported on her activities and referring to her as ‘Celia’ during the hearing.

He states he could not remember going to pickets outside Harlesden Court where the inquest into Peach’s death was held, although he reported on it:

‘If there is a report, then I must have gone.’

There were two reports, [UCPI0000013435] and [UCPI0000013498] that show Gray was organising the selling of Socialist Working papers at the event.

Despite a general call-out from the SWP to attend to Blair Peach’s funeral, Gray says he didn’t go. However, photos were taken at the funeral by a separate Special Branch unit. These were collected in an album brought to the office meetings of the SDS for the spycops to identify the people present. It was then used by Gray in standard reporting [UCPI0000013539]. He still says the killing was not discussed.

THE KILLING WAS NOT DISCUSSED

Vince Miller said that demonstrations were discussed during meetings at the safe houses, and there was:

‘informal exchange of information, but also a release so that you could actually talk about things somewhere.’

He too claims that Peach’s death was never talked about.

There are multiple reports from spycops about the 1977 Lewisham and Wood Green demonstrations, both of which featured clashes between fascists, anti-fascists, and the police. There are hardly any about Southall. Every spycop asked about this demonstration has clammed up, even ones who have been quite forthcoming about their other activities.

It is insulting to be expected to believe that neither reports, which were written on the minutiae of people’s lives, nor memories of an event where a member of the public was killed by police, remain within the SDS.

OFFICERS HOLDING OFFICE

There is some contention as to whether spycops were supposed to hold office of any kind, or take influential roles, within the organisations they infiltrated. What is certain is that most of them did.

One of the officers in this era was Richard Clark (‘Rick Gibson’ HN297, 1974-76). He set up a branch of the Troops Out Movement as part of a long-term climb through the ranks to the very top of the organisation, where he then sabotaged it – as we reported earlier.

In the period under examination, from Clark onwards, every single undercover officer took a role in the organisations they infiltrated, except for ‘Graham Coates’ (HN304, 1976-79) who was infiltrating anarchists without hierarchy or official roles.

In some case officers took national leading roles. What resulted from this was not just information, but also the opportunity to have a say in the direction of the organisation, and ultimately the ability to derail that organisation.

This week alone we’ve heard from:

‘Vince Miller’ (HN354, 1976-79)

Treasurer, SWP Walthamstow branch

Treasurer, SWP Outer East London District

Social Committee, SWP Outer East London District

‘Colin Clark’ (HN80, 1977-82)

Treasurer, SWP Seven Sisters & Haringey branch

Treasurer, SWP Lea Valley District

National Treasurer, Right to Work Campaign

Offered a place on SWP Central Committee; turned it down, but did do admin at HQ.

‘Bill Biggs‘ (HN356/124, 1977-82)

Treasurer, SWP Plumstead branch

Newspaper Organiser, SWP Plumstead branch

Treasurer, Briston SWP branch

‘Paul Gray‘ (HN126, 1977-82)

Newspaper organiser, SWP Cricklewood branch

Newspaper organiser, SWP North West London District

Acting Chairman, Coordinating Committee, Anti-Nazi League West Hampstead branch (later Camden Against Racism/Anti-Nazi League -West Hampstead & Hampstead Group)

‘Michael James‘ (HN96, 1978-83)

Newspaper organiser, SWP Clapton branch

SWP Hackney District Committee

Membership & Affiliation Secretary, Troops Out Movement

Chair of Steering Committee, Troops Out Movement

‘Phil Cooper’ (HN155, 1979-83)

Treasurer, Waltham Forest Anti-Nuclear Campaign

National Treasurer, Right to Work Campaign

In 1982 and 1983, Cooper was trusted enough to gather the entrance money for the SWP’s annual national delegate conference in Skegness. This provided him with a list of 1,983 attendees, which he included in his report that was passed to MI5 [UCPI0000018180].

It was noted by MI5 that ‘the SDS office [was] still groaning under the weight of Cooper’s report’, which was subsequently considered to be of significant value to the Special Branch and MI5 alike [UCPI0000028728, MPS-0730009, MPS-0735901].

UNRELIABLE WITNESS

Cooper is not being called to give oral evidence due to his current state of health. However, he has previously provided an updated and amended written statement.

A big question is whether Cooper told the Undercover Policing Inquiry’s risk assessors that he engaged in sexual activity whilst he was deployed.

The assessors were employed by the Metropolitan Police to determine the risk to former undercover officers if any aspect of their identity was revealed. Their report from late 2017 recorded Cooper accepting that he had had two or three encounters with women, and the circumstances in which they took place [MPS-0746710].

Both the author, David Reid, and the second risk assessor, Brian Lockie, were left with the impression that Cooper was describing his own experiences whilst deployed [UCPI0000034397].

In contrast, Cooper suggests both misinterpreted his comments, saying that he:

‘was not as clear as I should have been about the dividing line between the specific, factual details of my particular deployment and more hypothetical comments about such deployments more generally.’

Cooper now denies engaging in any sexual relationships while undercover.

The psychological assessors who spoke to Cooper ahead of the Inquiry say that he is not a reliable witness due to being both highly suggestible, and wanting to avoid subjects that would mean revisiting traumatic experiences [UCPI0000034361], [UCPI0000034360].

CHANGING PARAMETERS

The last witnesses to appear at the Tranche 1 Phase 2 hearings of the Inquiry were the two risk assessors in question, David Reid [MPS-0746378] and Brian Lockie [MPS-0747533]. They were called by lawyers representing a number of undercover officers, including Cooper.

Both were asked to explain some alleged factual errors in their risk assessments for other officers. This line of questioning seemed to aim at undermining the accuracy of their recollections of Cooper’s testimony about his sexual encounters.

Both Reid and Lockie reaffirmed that what they recorded Cooper saying was correct, although they conceded that they were ‘not infallible’.

We also learned that the risk assessment process had been an evolving one. The assessors have been learning as they went, and changing their protocols and procedures accordingly.

It is unclear what this means for the earlier risk assessments, which were used to justify secrecy around the names of SDS undercovers.

WHAT NEXT?

May 13 concluded this round of hearings. The next hearings – ‘Tranche 1 Phase 3’, examining SDS managers 1968-82 – are scheduled for some time in the first half of 2022, but there will be no certainty of the dates for some time.

Though the Inquiry admitted in 2017 that more than 1000 groups were targeted by spycops , it refused to publish the list and for a long time only named fewer than 100. Activist researchers have produced a more complete list of those targeted.

Kate Wilson: Verdict expected

During the first set of hearings in November 2020, the Inquiry disclosed another 126 names of groups that were spied on in 1969-1975. An updated list, with groups named during the current set of hearings, is being put together by the Undercover Research Group (URG) at the moment.

We also hope to receive the verdict in the case of Kate Wilson before the end of this year. Kate was deceived into a relationship by undercover officer Mark Kennedy. Her ten-year legal battle for answers recently culminated in a hearing at the Investigatory Powers Tribunal, at which police admitted their spying breached a number of her human rights, including her fundamental right to freedom from torture, inhuman or degrading treatment.

Regardless of the verdict, however, this landmark case and the disclosure resulting from it is bound to have consequences for the Undercover Policing Inquiry, as it reveals details that the police have been trying hard to keep concealed. Watch this space.

More details can be found in last week’s reports, and in

More details can be found in last week’s reports, and in  This is the second of our weekly reports on the current round of Undercover Policing Inquiry hearings examining the actions of the Metropolitan Police’s undercover political unit, the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS), from 1973-82.

This is the second of our weekly reports on the current round of Undercover Policing Inquiry hearings examining the actions of the Metropolitan Police’s undercover political unit, the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS), from 1973-82.

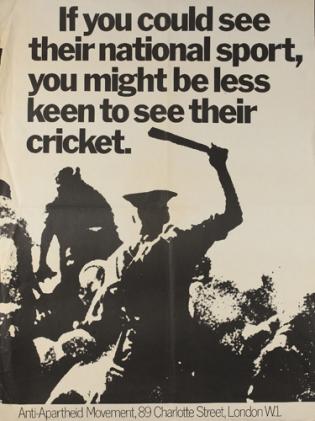

While the AAM resorted to mainstream methods, younger people wanted to do more. This is how the

While the AAM resorted to mainstream methods, younger people wanted to do more. This is how the

The third week of the

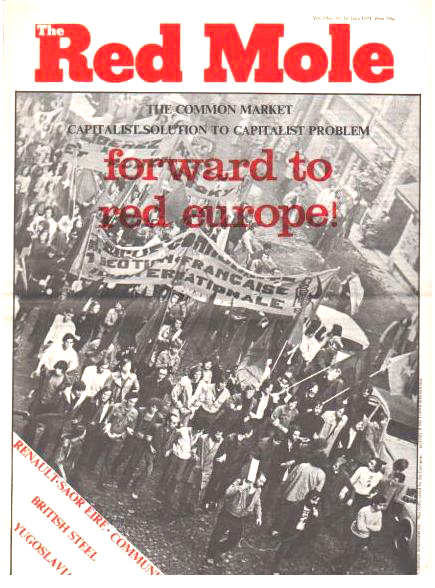

The third week of the  His managers did, however, instruct him to attend the Conference for a Red Europe in Brussels in November 1970, organised by the Fourth International (of which the IMG was a part).

His managers did, however, instruct him to attend the Conference for a Red Europe in Brussels in November 1970, organised by the Fourth International (of which the IMG was a part).

Undercover Policing Inquiry

Undercover Policing Inquiry

Undercover Policing Inquiry

Undercover Policing Inquiry