UCPI Daily Report, 20 May 2022

Tranche 1, Phase 3, Day 10

20 May 2022

Witness:

Trevor Charles Butler (officer HN307)

This was the last day of the 2022 round of the Undercover Policing Inquiry hearings, which have examined Special Demonstration Squad managers 1968-82.

The day began with the Inquiry’s Elizabeth Campbellon reading out summaries of evidence relating to three men who worked in the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) back office towards the end of this period covered by this ‘tranche’.

Richard Reeves Scully (officer HN2152) joined Special Branch in 1968. He’s not entirely sure when he was sent to work in the SDS back office, but it’s thought to have been around 1977. His role was handed over to Paul Croyden in 1979.

Witness statement of Richard Reeves Scully

Paul Andrew Croyden (officer HN350) served in the SDS for two years, from July 1979 to August 1981.

Witness statement of Paul Croyden

Christopher Skey (officer HN308) was also part of the SDS for around two years, and then spent a year as Liaison Officer between Special Branch and the uniformed public order unit (aka ‘A8’). Skey provided two witness statements, one in 2020 and another in 2021 which added a little more detail about his time as a Liaison Officer.

The Inquiry also published documents relating to two deceased senior officers:

Ken Pryde (officer HN608) was described as “the Detective Chief Inspector in charge of the SDS from November 1977 till early 1978” – although this doesn’t correspond with what the Inquiry has told us elsewhere.

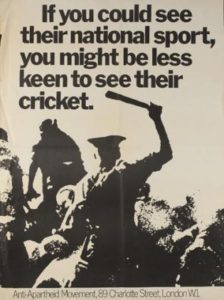

Mike Ferguson (officer HN135) is said to have run the unit from January 1978 until February 1980, having spent time undercover himself ten years earlier (reporting on anti-apartheid campaigners like Peter Hain).

Trevor Charles Butler (officer HN307)

David Barr QC

On this final hearing of 2022 the Inquiry heard oral evidence from one man: Trevor Charles Butler OBE (officer HN307). He was recruited to the unit in 1979 and left in 1982. He was questioned by David Barr QC, Counsel to the Inquiry.

This was a notably reticent witness, who favoured one-word answers (and often that word was “no”).

In his witness statement, Butler referred to True Spies, the 2002 BBC documentary series that detailed the work of the SDS, as:

“an earth-shattering breach of the ‘need to know’ principle”

It’s clear he sees the Inquiry in the same light. Safeguarding a ‘need to know’ principle is his vocation, and he treated the Inquiry as a violation of that.

Butler claimed to remember very little about events that took place in the 1970s, including his time in the SDS and in other parts of Special Branch.

Butler attended police training courses, and learnt about the main principles of police powers, but freely admitted not bothering to consider these while he was in the SDS.

He said that he didn’t think normal police discipline regulations – covering, for example, sexual misconduct – applied to the spycops as they were:

“experienced, trustworthy men, who I had no concerns about.”

He was happy to go along with existing day to day practice, and very happy with the SDS’s method of unfiltered reporting (hoovering up as much information as possible and putting it all on file). He doesn’t seem to have gone out of his way to question anything, to consider doing things differently, or to actively review deployments or assess their value.

He had no qualms about officers stealing dead children’s identities, and said he had no idea that other undercovers had been issued with British Visitor Passports, which did not require a birth certificate.

Butler recalled little contact with the senior managers above him, saying:

“We were left to our own devices”

This was due in part to the move of the SDS office out of New Scotland Yard to Vincent Square. He also professed to be unaware that some of them had previously been involved in running the unit.

He couldn’t recall why the SDS 1979 Annual Report said that “covert policing is being subjected to increasingly close and critical scrutiny” or any concerns at this time about the spycops’ relationship with the Security Service (aka MI5).

There were a lot of subjects that he claimed no recollection of at all.

SUBVERSION

He says that he didn’t receive any training of the type listed in the 1979 ‘Initial Training for Special Branch Officers’ Agenda. He relied on his own “common sense” to guide his understanding of what was or was not ‘subversive’.

He didn’t recall seeing Special Branch’s 1970 Terms of Reference, and its definition of the word ‘subversion’, before. During this period, the Security Service actively tried to expand the working definition of ‘subversion’, and a slightly different definition appeared in a Circular sent out to Chief Constables in 1974 (referring to industrial disputes) . Butler says he doesn’t recall seeing this either.

A similar Circular, referring to subversive activities in schools, was sent out in 1975. Butler does not recall any sensitivity around reporting on school-children, or the School Kids Against the Nazis.

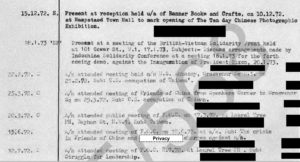

COMPREHENSIVE COLLECTION OF DATA

What were the most important things the SDS did?

According to Butler’s written statement, the main aims of the SDS were public disorder and collecting information to update Special Branch’s files.

Addressing the second of these, Barr asked him to explain why this was so important, and what such information was used for – for example, was this related to public order?

According to Butler, after some waffle, such details weren’t always immediately important, but might have what he called “latent value” – meaning they might

“possibly be relevant at a future date.”

Might the information be used for vetting purposes?

In paragraph 129 of his statement, Butler admits that “parts may seem unacceptable in today’s context” and Barr quoted the whole thing, ending with:

“I do not believe that individuals finding their names on a Special Branch or Security Service file is too high a price to pay for comprehensive intelligence coverage, providing that those individuals were not unlawfully discriminated against because of this.”

Barr asked him to explain what he meant by this, and Butler admitted that he must have been referring to people losing their jobs or being blacklisted – he says this is “unacceptable” but insists that it would only have happened if such information was ‘leaked’ from Special Branch, and he doesn’t believe this happened:

“I’m convinced that Special Branch records were properly maintained and there was no leakage.”

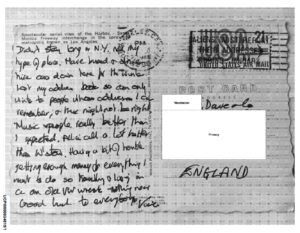

We saw the kind of information that was kept on file for its ‘latent value’ – contact details copied from the address book of “a leading member of the Freedom Editorial Collective”.

Having established that ‘N/T’ stands for ‘No Trace’ – it is clear that the majority of these names have not already come to the attention of Special Branch. These names were retained for decades and Butler doesn’t see it as a problem.

Asked to explain how gathering intelligence on individuals assisted with public order, he claimed that this would enable the police to make arrests after disorder had occurred. The SDS were quick to claim their public order ‘successes’ but nowhere is this kind of success mentioned.

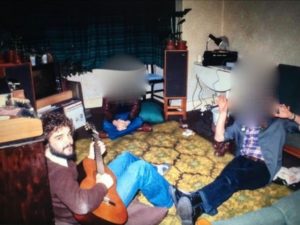

PLAYING SQUASH WITH THE BOYS

Trevor Butler liked to play squash with his colleagues. Because of something Barr said today, we now know that he also played squash with the guys from the Security Service as well (a minor detail that was redacted – and replaced with the word ‘sport’ – in one of the documents released by the Inquiry).

He says he got to know the officers:

“some of them very well, others not so well, but reasonably well, all of them”

The unit was an all-male environment. Butler remembers banter and jokes. Were any of these of a sexual nature?

“I can’t remember, but probably”

However, he insists that he heard no suggestion of spycops being the subject of sexual advances, and nothing about sexual contact actually occurring. He said he didn’t consider this to be a risk:

“they were married men with a stable background who I trusted not to get involved sexually outside of their marriage.”

He says he never asked them if they had come under “pressure to indulge in sexual activity” never mind asking directly if they’d engaged in any form of sexual contact.

If this is true, then the lack of curiosity exhibited by him and other managers clearly demonstrates a culture of ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ within the SDS. He didn’t remind them not to engage in sex on duty, consider setting up ‘cover girlfriends’ or finding other ways of reducing the risk.

Rick Clark (‘Rick Gibson’, officer HN297, 1974-76) is known to have had at least four relationships; he was investigated by the group he infiltrated, Big Flame, and was exposed as a result. Butler claims he can’t remember anything about this.

Similarly, he says he didn’t hear any gossip about ‘Jim Pickford‘ (officer HN300, 1974-77), withdrawn after falling in love with an activist, who he went on to marry.

BARRY’S GIRLFRIEND

Another incident was discussed in more depth. ‘Barry Tompkins‘ (officer HN106, 1979-83), in his witness statement, details a ‘platonic’ relationship with a woman that he met while undercover. He says they were just friends, and he slept in her home – supposedly in her child’s bedroom with a noisy hamster – a few times, rather than driving home drunk.

This woman was often referred to as “Barry’s girlfriend” amongst those he was infiltrating. Tompkins says that he was asked by his manager, Trevor Butler, to account for an intercepted phone call in which an activist had talked about storing “items from Ireland” at “Barry’s girlfriend’s place”.

“I think Trevor said something along the lines of ‘You’re not going to get us in trouble, are you?’ and I simply said ‘no, it’s nothing like that’.”

Butler says he does not recall this at all. He categorically refuses to accept that this may have happened but he forgot about it (like everything else). He is adamant that Tompkins must have confused him and another manager from the office.

Asked what he thinks he might have done if these events had occurred as laid out in Tompkins’ statement, he says “my outlook was probably different then than it is now”, yet goes on to say that he can’t remember what his outlook was then.

Barr was somewhat flummoxed by this and points out that if he doesn’t know what his outlook was before, how does he know it’s changed?

“Now, I think I would have insisted that he ended such a relationship. Then, I might have been more tolerant.”

Butler explained that he has become less tolerant since becoming “older and more disagreeable” (his words, verbatim).

In those days, he goes on, he wouldn’t have been concerned about a platonic relationship like this. Would he have investigated to find out if more was going on?

“That’s a hypothetical question. It didn’t happen.”

But he added:

“I would have investigated very thoroughly.”

Would a sexual relationship have led to disciplinary action? Butler says he would have made sure the officer left the SDS, but agreed that there might have been difficulties taking formal disciplinary action, and that decision would have been ‘above his pay grade’.

Another exhibit was shown: a Security Service note about a visit to the SDS – in the shape of senior managers ‘Sean Lynch‘ (officer HN68) and Dave Short (officer HN99) – in June 1982, after Butler had left. It contains the remarkable line:

“Information on this subject may be bedevilled by the fact that HN106 [‘Barry Tompkins’] has probably bedded [privacy] and has been warned off by his bosses.”

Does he know what this refers to? Is is something he told Dave Short? Unsurprisingly, Butler can’t help with this as, yet again, he can’t recall. (NB: Tomkins himself says that this refers to a different woman, who the Security Service wanted to use as an informant, and who he denies sleeping with).

In his witness statement Butler says that he knew ‘Barry Tompkins’ was married with young children at the time.

“I would have reminded him about his obligations to them and to the job in fairly strong terms if I had even the slightest suspicion that he had or was tempted to stray.”

Barr put it to him that this demonstrated consideration of the possible impact on this marriage, and of the risk to both the SDS and the wider Met, but none for the woman who ‘Barry’ had formed this close friendship with. Butler confirmed that he did not or would not have given her any consideration at all.

NO CONSIDERATION FOR WOMEN

Other officers that are known to have had sexual relationships in this era include Vince Harvey (‘Vince Miller’, officer HN354, 1976-79), with four women; officer HN21, with one woman; and ‘Paul Gray’ (officer HN126, 1977-82).

Butler says he gave zero consideration to the harm that any of these women may have suffered as a result.

He said he knew ‘Phil Cooper’ (officer HN155, 1979-84) quite well, but

“he didn’t give me any reason to suspect that his behaviour was cause for concern.”

He added that Cooper wouldn’t have confessed to doing sex and drugs to Butler anyway as it would have led to trouble for him.

Barr read out a declaration from Butler’s statement:

“As far as I was concerned, then and now, the SDS provided a terrific service’ trouble-free”

Did he still think that, in light of all this evidence?

Butler asserted that:

“I considered I was extremely lucky. I had a couple of years working with a very successful team who presented no problems and I suspected were doing nothing untoward.”

The strength of his loyalty to the SDS is very clear throughout. Pressed about the sexual misconduct that has come to light, the most critical comment he could make was to say that he was “disappointed”.

REPONSIBLE ROLES

Troops Out Movement demonstration at military recruitment office

Butler’s statement refers to undercovers not “crossing the line between acceptable recording and unacceptable direction setting and incitement”, so Barr explored this topic.

In his witness statement, ‘Mike James‘ (officer HN96, 1978-83) said that he’d been advised by colleague ‘Geoff Wallace’ (officer HN296, 1975-78) not to get too involved, or become too prominent, in the groups he was infiltrating.

However, he was elected to the Hackney District Committee of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) and chaired meetings of the Party’s Clapton branch, becoming their ‘District Book Organiser’.

The same officer was then encouraged by his bosses, in around 1980, to get more involved in the Troops Out Movement (TOM), and ended up being elected as TOM’s Membership and Affiliation Secretary.

He didn’t get a chance to discuss this with his managers beforehand – the nomination “came out of the blue” – but says he told them as soon as he could and they were “pleased” with this news.

Butler cannot recall being one of those managers. However he agreed that this would have been seen as “a good thing” as it gave the SDS much more access to information.

He didn’t view this position (which came with a seat on the TOM’s national steering committee) as a problem. He says he wouldn’t have interfered, just trusted the officer’s judgement as to what he felt “comfortable” with.

‘Paul Gray’ (officer HN126, 1977-82) also spied on the SWP, rising beyond branch roles to join its North West London District Committee. This was also “a good thing”, according to Butler.

Surely this meant he could be voting on things and influencing the direction of the group? “I don’t know what they did” was Butler’s response.

Asked if he, as the manager receiving information, he tried to find out what they did, Butler simply answered “no” as a sentence in its own right. Again.

SPYCOPS’ WIVES

Before new undercovers went out into the field, Butler would visit their wives at home. He would explain that their husbands’ working hours and appearance would change, but nothing more about what this “important work” actually entailed.

He says he wanted to ensure they “were happy to support their husband in the role” and “understood the difficulties” – i.e. the disruption to family life caused by long, irregular hours. He agreed that the SDS asked a great deal of these officers’ wives.

ANTI-RACIST ACTIVISM IN 1981

‘Funeral of Winston Rose’ – painting by Denzil Forrester

‘Barry Tompkins’ (officer HN106, 1979-83) reported on a meeting that took place in Walthamstow in August 1981, organised by the Winston Rose Action Committee.

They were campaigning for a public inquiry into the death in custody of Winston (a 27-year-old boxer, who had been born in Jamaica) a month earlier.

One of the speakers was Fran Eden, of East London Workers Against Racism (ELWAR), a group which Tompkins had infiltrated. Butler was asked what he thought the policing value of this reporting was.

Barr ventured to suggest that sending an undercover officer to spy on such a meeting might not be good optics for the Met, and could risk “doing more harm than good”. If he’d been discovered, might that not have served as a catalyst for the community to take to the streets, as they had done in Brixton and other places around the country already that year?

Butler’s said “that could probably be said of every report that an undercover officer submitted”, doubling down on his opinion that “it was wholly justified and a fine report”.

He had no concerns about Tompkins reporting on a Revolutionary Communist Tendency meeting that took place in Brixton directly after the riots, on 16th April, about setting up South London Workers Against Racism, organising legal defence for members of the local community, involving legal representatives.

Also in April, Tompkins reported on ELWAR holding an election meeting in Stoke Newington Town Hall, as one of their members was standing as a candidate in the upcoming local elections.

Barr suggested that electoral activity isn’t exactly subversive.

But in Butler’s view, if a group’s worth reporting on, then it’s worth reporting on every single thing they do:

“my attitude was always it’s far better to report too much than too little.”

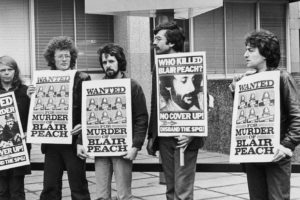

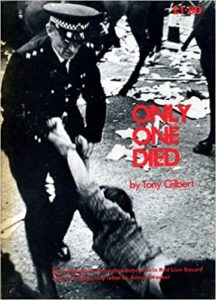

BLAIR PEACH

Blair Peach’s funeral, East London cemetery, 13 June 1979

Just like the other managers we’ve heard from at the hearings, Butler said he barely remembered the events around police killing Blair Peach and the subsequent justice campaign. It is yet another stretch on his credibility.

According to the SDS 1979 Annual Report, there was “a sustained campaign to discredit and criticise the police” after Peach’s murder. Butler admitted that he may well have written this.

The SDS reported on these campaigners, but Butler insisted that the Metropolitan Police’s only interest in such intelligence would be due to potential disorder, nothing to do with collecting information about people who were critical of the police.

Barr pointed out that there was “very little trouble indeed” from the justice campaign, and asked why the Friends of Blair Peach were described in that way.

Butler ended up in another awkward dance, trying to avoid the point that the justice campaign was deliberately targeted for calling for accountability from the police. He did at least concede it was inappropriate to take photographs of mourners at Peach’s funeral.

MESSED-UP PRIORITIES

The SDS 1980 Annual Report said that “anti fascist activity continued to tax the resources” of the police.

Butler explained that when it came to confrontations between the far right and the far left, the police tended to blame the anti-fascists for causing (or as he re-worded it, ‘creating’) serious disorder, for “attacking those they opposed”.

He said the police were also “a good target” for the demonstrators.

He grudgingly admitted that the far right were responsible for lots of serious street violence, but said it wasn’t the SDS’s job to predict or prevent racist attacks, who were “more interested in large scale social disorder”.

His attention drawn to the section of the SDS 1981 Annual Report headed ‘Security’ (on page 7). Operational security is described as always being “of paramount importance” for the unit – both for the “personal protection of the field officers and to prevent embarrassment to the Commissioner by its existence becoming public knowledge” – and the “political sensitivity” around the SDS operations is mentioned.

Squeezing blood from the stone, Barr got Butler to admit that such ’embarrassment’ would stem from the public learning that undercover policing tactics weren’t restricted to drugs gangs and serious criminality, but were also being used in a political way, “to manage public disorder”.

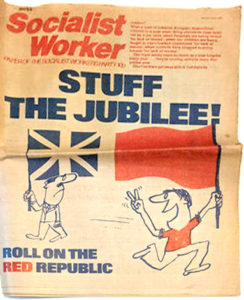

CND protest, London, October 1981

Barr went on to note that the Report says that all infiltrations had to be fully justified on the basis of the Commissioner’s responsibility for the preservation of public order.

Under the heading ‘Coverage’ (on page 4) is a list of groups whose infiltration would be hard to justify on these grounds, such as Womens Voice, the Freedom Collective, and the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND).

Butler claimed not to know who the first two were, but even he couldn’t pretend not to have heard of CND, a hugely popular campaign that held protests hundreds of thousands strong.

Instead, he suggested that CND demonstrations were often ‘infiltrated’ by “extremists”, and then added another explanation for spying on them: that the SDS didn’t have enough undercovers to infiltrate all of the groups, but many of those people attended CND events.

We now know that CND was infiltrated, in its own right, by John Kerry (officer HN65, 1980-84) but Butler claimed he wasn’t involved, saying this must have happened as he was leaving. However Kerry joined the unit in 1980 and Butler didn’t leave until 1982.

HOME OFFICE: PLAUSIBLE DENIABILITY

In his statement, Butler recalled meeting for “a beer and a lunch” with a relatively senior Home Office official every month.

In his statement, Butler recalled meeting for “a beer and a lunch” with a relatively senior Home Office official every month.

His bad memory returned when he was asked about these meetings – he couldn’t remember their purpose or anything about what business was discussed at them, but says that he knew that it had no influence over the unit’s work.

The SDS was set up by the Home Office in 1968, and was directly funded by them for twenty years. Funding had to be applied for and renewed annually.

The 1976 authorisation for the Special Demonstration Squad’s continued existence was signed off by Robert Armstrong, later Baron Armstrong of Ilminster. He was Cabinet Secretary and Head of the Home Civil Service. It is difficult to imagine a more highly placed civil servant.

The Security Service’s ‘Witness Z’ has previously told the Inquiry:

‘the pressure to investigate these organisations often came from the Prime Minister and Whitehall’.

Put simply, the existence and functioning of the SDS was known of, and authorised, at the very top.

There is nothing embarrassing to the police or Home Office about preventing crime. But the destabilising of democratic movements, the wholesale and widespread intrusion on citizens, and their exploitation for political advantage? That is worth keeping secret.

Every annual application for funding refers to the officers fully recognising ‘the political sensitivity’ of the unit’s existence. Authorisation is only ever granted ‘in view of the assurances about security’. In other words, as long as you can promise us we will not get caught, you can carry on.

There appears to have been a lot of careful work to ensure no proof of the link survives. After the spycops scandal broke, in 2015 former Audit Commission director Stephen Taylor looked into the links between the SDS and the Home Office. His report said the ‘investigation did not identify any retained evidence available in the Department of any correspondence, discussions or meetings on the SDS for the 40 year period’ that the unit existed. Nothing. In the entire Home Office.

Time and again Taylor found reference to a file, catalogue number QPE 66 1/8/5, understood to have covered Home Office dealings with the SDS. It has disappeared. It would have contained material classified Secret or Top Secret, which would have strict protocols around its removal or destruction, yet there is no clue as to what happened to it.

They physically searched all storage facilities in the Home Office. It’s gone. Taylor couldn’t make allegations but rather pointedly said ‘it is not possible to conclude whether this is human error or deliberate concealment’.

Butler appears to be well acquainted with the Home Office’s stipulation that details of their involvement must never come to light.

DRINKING ON THE JOB

Finally, Barr asked Butler some questions on issues raised by the Inquiry’s Non State Core Participants (ie, victims of spycops).

One significant issue had been about the spycops’ consumption of alcohol whilst on duty.

Butler was asked about their expenses claims, and clarified that they were not allowed to claim for alcohol they’d drunk, unless it was as “part of a substantial meal”.

He admitted that they could have claimed for drinks consumed by other people, which would have “been shown as an incidental expense”, but had no recollection of any of them doing so.

In his words, most of the officers “drank regularly but not excessively”. He contradicted other witnesses by saying they “usually had a beer” when they met at the safe house.

He went on to explain that they wouldn’t want to drink so much as to be drunk in their activist group, or be caught drink-driving (as having a driving licence was important for their jobs). This contradicts countless reports from the people who were infiltrated.

He had no concerns about anyone drinking to a level that impaired their judgement or affected their long term welfare.

Was he concerned about them buying lots of drinks for those they were spying on? No. He assumed they would buy rounds when out with activists, but “you wouldn’t buy excessive drinks just because you could afford to.”

DEPARTURE

The last thing we heard about from Butler was about his leaving the SDS. He was told by Commander Wilson that he was being moved on, ostensibly on the grounds that he was getting too close to those he managed and losing his objectivity:

“he said that it was time for me to move on to another role before I unquestioningly took the side of the UCOs [undercover officers] in all matters.”

It seems likely that had something to do with him fighting their corner on the issue of overtime payments, possibly another illustration of his loyalty to the undercovers. He continues to insist that they did an “excellent job”.

WHEN WE MEET AGAIN

The Inquiry’s Chair, Sir John Mitting, then closed this round of hearings with the line:

“When we’ll meet again remains to be seen.”

The next set of evidential hearings (covering ‘Tranche 2’, the SDS 1983-92) are not due to take place until 2024. In the meantime there may be an interim report from the Inquiry to look forward to.

Witness statement of Trevor Butler

Transcript, video of the morning and afternoon the day’s hearing

The eighth day of the 2022

The eighth day of the 2022

![Albert Meltzer in his bookshop [pic: Phil Ruff]](http://campaignopposingpolicesurveillance.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Albert-Meltzer-1960s-229x300.jpeg)

Next, Barr explored Trotskyists groups such as the International Marxist Group (IMG), International Socialists (IS, later Socialist Workers’ Party) and the Socialist Labour League (SLL, later Workers Revolutionary Party).

Next, Barr explored Trotskyists groups such as the International Marxist Group (IMG), International Socialists (IS, later Socialist Workers’ Party) and the Socialist Labour League (SLL, later Workers Revolutionary Party). Barr took him through a number of reports which bore his name. Creamer said that while reports were signed by him, that might be a cover for the undercover sourcing the material. Barr pointed out on that the language in the

Barr took him through a number of reports which bore his name. Creamer said that while reports were signed by him, that might be a cover for the undercover sourcing the material. Barr pointed out on that the language in the

![Anti-racist protesters, Lewisham, 13 August 1977 [Pic: Syd Shelton]](http://campaignopposingpolicesurveillance.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Anti-racist-protesters-Lewisham-13-August-1977-300x195.jpg)

The third day of the 2022 Undercover Policing Inquiry hearings concerning the management of the Special Demonstration Squad 1968-82 included opening statements from:

The third day of the 2022 Undercover Policing Inquiry hearings concerning the management of the Special Demonstration Squad 1968-82 included opening statements from:

Morris mentioned one spycop, ‘Tony Williams’ (

Morris mentioned one spycop, ‘Tony Williams’ (

Proceedings opened today in the third round of evidential hearings in the

Proceedings opened today in the third round of evidential hearings in the