UCPI Daily Report, 4 Nov 2020

Tranche 1, Phase 1, Day 3

Tranche 1, Phase 1, Day 3

4 November 2020

Evidence from:

Oliver Sanders QC (Designated Lawyer Officers i.e. speaking for 114 spycops)

Richard Whittam QC (Slater & Gordon Clients representing 12 individual undercover officers / managers)

David Lock QC (whistle-blower officer Peter Francis)

Angus McCullough QC (Category M Core Participants – three ex wives of undercover officers)

Rajiv Menon QC (spied-upon core participants represented by Jane Deighton & Richard Parry)

Oliver Sanders QC

(Designated Lawyer Officers)

Oliver Sanders QC

Oliver Sanders QC, representing the majority of former spycops, concluded the opening statement he’d begun at yesterday’s hearing.

Sanders said the main function of the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) was to assess public order threats, of which many came from political protests in the period currently being examined by the Inquiry (1968-82). However, he said it’s hard to quantify because few records have been kept and even at the time intelligence was ‘sanitised’ to obscure its source.

He turned to the SDS’ secondary function, providing intelligence on ‘subversion’ to MI5. He conceded that subversion is an amorphous concept and ‘difficult to grasp as a threat to national security’ but insisted it was a real threat then and now. He cited hostile states sponsoring cyber attacks as subversion, as if that has anything to do with those of us targeted by spycops. It was an extension of the previous day’s repeated iterations of ‘undercovers protect us from terrorism and paedophiles’, a tactic which only serves to smear victims of spycops.

MI5’s FOOT SOLDIERS

Sanders was keen to emphasise that the SDS was no aberration in its choice of targets, merely reinforcing the established work of MI5. He cited The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 by Christopher Andrew (2009), which estimated that in the 1970s a quarter of MI5 resources went on counter-subversion.

In 1980s the groups that fell under this category included the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (which had around 250,000 members and was mainstream enough to have its aims included in the Labour Party manifesto), trade unions such as the National Union of Mineworkers, and an array of left wing organisations including the Socialist Workers Party, International Marxist Group, and the Militant Tendency.

He said that MI5 and spycops were so allied that MI5 considered funding the SDS, and they liaised to ensure they didn’t duplicate spying – it would not only have wasted resources but they may have ended up spying on each other’s officers.

Most SDS intelligence reports were not only copied to MI5 but were sent with the file reference numbers of the people/group already added. The partnership was active, with MI5 recommended tips to SDS spycops, and they asked for specific info – though he didn’t mention any instances of the flow of information and directives going the other way. Instead, it seems the SDS was used as the foot-soldiers of MI5. Sanders noted that the SDS weren’t in a position to question MI5’s focus, thinking and efforts.

Sanders was at pains to assert that there was nothing sinister, surprising, or objectionable in this collusion, it’s just what both organisations were tasked to do.

The subtext of Sanders’ explanation was that, because MI5 targeted the same people in the same ways as the SDS, it means the SDS was acceptable rather than both of them being unacceptable.

PART OF THE UNION

Sanders then made a few tenuous claims about the limits of SDS activity. He unequivocally stated that the SDS did not have any involvement in industrial blacklisting. It did not target justice campaigns, members of parliament or trade unions directly, it was merely inevitable collateral collection while spying on other things.

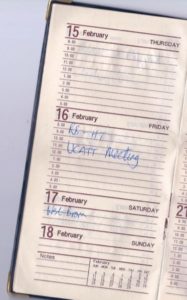

Page from undercover officer Mark Jenner’s 1996 diary, showing his attendance at a UCATT meeting

Mr Sanders appears to have short-term memory issues. On Monday this week, David Barr QC, Counsel to the Inquiry, confirmed that in its earliest years, the SDS spied on the Shrewsbury 2 Defence Committee, a group in support of trade union activists who’d been fitted up with charges after their invovlement in the 1972 building workers’ strike.

Peter Francis was in the SDS from 1993-1998, and believes intelligence he gathered was used in construction industry blacklisting.

SDS officer Mark Jenner was a member of construction union UCATT.

Officer Carlo Soracchi was often on picket lines, and was photographed on an RMT picket in 2004 calling for the reinstatement of Steve Hedley.

Hedley went on to become general secretary of the union and is also a core participant at the Inquiry because it’s credibly established that he was spied on for his trade union activity.

Sanders said talk of the SDS spying on thousands of groups is wholly wrong. Once again, he’s arguing with the Inquiry itself, as that is the source of the fact that more than 1,000 groups were targeted. Sanders did not suggest what sort of figure he would like us to believe.

SPYCOPS STEALING DEAD CHILDREN’S IDENTITIES

Sanders then peeled a figurative onion and tried to sound a bit sad as he came to the issue of spycops stealing the identities of dead children to use as the basis of their undercover persona. He said it was invented in an earlier time when people felt differently about death and risk, and doing this to protect people who were still alive would probably have been OK with the families involved.

He said it was done because having a real birth certificate was the only way to prove a person was real. It was lawful, he reckoned, as ‘it didn’t involve quote-unquote theft’ he said. To the rest of the world, taking someone’s identity without the knowledge of them or their family and then using it to pretend to be them is a solid definition of identity theft.

Sanders said that though it was regrettable, if spycops hadn’t stolen dead children’s identities they would have been at greater risk of exposure, or else there would have to be no spycops and the alternative to that was paramilitary police on demonstrations. So, it was an unpalatable choice but obviously the best of a bad bunch.

This lawyer representing UK police officers, a force that supposedly prides itself on policing by consent, is saying anyone wanting to be politically active must put up with being targeted either by spycops violating fundamental rights in our homes or paramilitary police threatening us on the streets.

Spycops, Sanders informed us, understand why stealing dead child’s identity is upsetting, some were even uncomfortable doing it at the time, but they felt there was no choice. There was no pleasure taken in doing it, and the police hope that is of some comfort. He said it happened until the 1990s.

Sanders doesn’t explain why, once spycops were stealing dead kids identities and the Home Office Select Committee demanded families were told in 2013, the Met refused. In the end the Inquiry had to tell them recently.

SPYCOPS DECEIVING WOMEN INTO RELATIONSHIPS

Sanders said a couple of his clients admit to deceiving women into relationships while undercover, and just two of them say it was long-term. But, unable to deny established facts, he conceded that it appears a significant minority of SDS officers entered into such relationships. These shouldn’t have happened and were wrong, he said.

His excuse was that many of the officers who deceived women into relationships were unsuitable for undercover work, and officers who did so were personal failures who’d lost sight of what they were supposed to be doing. This is palpable nonsense; the very opposite is true. Such relationships were standard practice, known to the managers and seen as integral to the job.

Far from being seen as inadequate misfits, several of the officers who perpetrated them were appointed as role models. SDS officer Bob Lambert deceived at least four women he spied on into relationships and had a planned child with one of them. He was promoted to running the SDS, where he deployed numerous officers who did the same. He received an MBE for services to policing.

SDS officer Andy Coles groomed a vulnerable teenager known as Jessica into a year-long relationship when he was undercover in the early 1990s. He went on to be an SDS cover officer, before being appointed to train the first officers of the SDS’ sister unit the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU). After that, he moved on to being Head of Training for the Association of Chief Police Officers’ Terrorism & Allied Matters committee, which oversaw the NPOIU.

SECRECY AND FEAR

Sanders then criticised the Inquiry itself. Its remit is too broad in covering 50 years. It’s also too narrow in only examining activity in England & Wales when spycops often went to other jurisdictions (like a stopped clock momentarily telling the right time, that last point is the bit of Sanders’ speech that does indeed have great merit).

Sanders accurately said that we can’t say what would have happened if there hadn’t been spycops. He then said the lack of this knowledge means the Inquiry will be inadequate, and that as we can’t say things would have been better, we can’t really say they were a bad thing overall.

He suggested that demonstrations may have been more violent and, as he did the previous day, invoked the death on protests of Kevin Gately and Blair Peach – both of whom were killed by police at events with heavily spied-on groups.

If Sanders’ reasoning were sound, we would expect any deaths to have been in unknown groups, and those who were infiltrated would have been safely policed. Instead, the very opposite happened. The spycops targeted the groups seen as dangerous threats, as did the most violent uniformed police in public order situations, all leading to the very worst consequences.

Sanders said a further limit on the Inquiry is the anonymity granted to many officers, including 34 out of the 74 he speaks for. This is, of course, the anonymity that officers have actively imposed on the Inquiry. But, Sanders said, if their identities were revealed some would be targeted and possibly killed.

Numerous spycops have been outed for years, including real names and photos. Some of them have outed themselves, appearing at advertised public events and doing media appearances. Many would be very easy to find. None have come to any harm, and it’s frankly insulting to victims to portray them as such a threat.

Neil Woods, a former undercover drugs squad officer scoffed at Sanders on Twitter:

‘I’ve gone public with my real name. And I actually did take down some dangerous people. Ridiculous to suggest that UC’s are at risk having infiltrated London Greenpeace or CND etc. But besides that, I ALWAYS understood that my anonymity was a privilege not a right.’

Sanders said that there was some genuinely dangerous work done by SDS officers, so secret that the Inquiry can’t talk about it, meaning that people will only hear about the pointless and outrageous activity and not have things in balance.

This crooked logic pretends that it’s a balancing act, that if you catch enough bad guys it’s OK to abuse some passers-by. The Met have admitted that spycops deceiving women into relationships is a violation of human rights including the right to freedom from torture, inhuman or degrading treatment. This is an absolute right that no circumstances can ever justify breaching. There is no pair of moral scales in which to put anything that can outweigh the abuses committed by spycops.

Despite all the admissions of abuse we’ve forced out of the Met in recent years, Sanders submitted that the SDS was lawful, effective and working in the public interest when gathering intelligence and helping MI5. ‘The SDS was a politically neutral cog as part of a much larger apparatus,’ he said.

There’s a right of free speech but no right to be heard or force views on others, he said. If we had a right to disrupt things without the police knowing it would have to be a right enjoyed by everyone and there would be mayhem. A lot of the groups targeted by the SDS wanted to promote their own views and suppress the views of opponents. It’s not fair to blame the SDS just because these groups had beliefs that were in conflict with the Met’s neutral job.

The accompanying written opening statement from Oliver Sanders QC on behalf of Designated Lawyer Officers

Richard Whittam QC

(Slater & Gordon Clients)

Richard Whittam QC

Richard Whittam spoke for Slater & Gordon clients, 12 individual undercover officers / managers.

He said that an uninitiated observer may think the Inquiry was just about spycops deceiving women into relationships, but it’s much more than that. However, it isn’t about blaming individual officers. The Inquiry will examine inappropriate deployment and tactics; management and supervisory structure, targeting and authorisation, reporting on justice campaigns, management’s attitude to relationships and commission of crime, the welfare of officers and their families. There are many more issues, Whittam said, but these are of particular importance to the people for whom he speaks.

Whittam said that officers can’t properly justify themselves because those who employed them adhere to the principle of ‘Neither Confirm Nor Deny‘ if anyone is an undercover officer (this tactic has been often been used by police to try to obstruct people getting the truth about spycops). The fact that the Met and Inquiry have confirmed the spycops, using ciphers to protect identity if they feel it necessary, means this assertion is simply not true in this case.

Officers committing crimes while undercover isn’t a problem, Whittam said, because there is some legal basis for allowing it. He expanded, saying the CHIS Bill proves the government see that commission of crime is an essential feature of undercover work in getting to the heart of groups that would cause the public harm. He didn’t pause to define public harm, nor to question whether the current government can be trusted as impartial and infallible moral arbiters.

Whittam turned to the personal well-being of the officers he was speaking for. He told us that their undercover careers and this Inquiry have had a significant impact on their mental health. He lamented that it was supposed to conclude in 2018 yet is only just beginning (neatly sidestepping that the bulk of the delays have come from the police).

Some of the officers he represents are further worried by campaigns to expose their identity. Some deceived women they spied on into relationships but, he said, it’s important not to judge the fact in isolation – one of these relationships continues to this day.

One of Whittam’s spycops, Jim Boyling, deceived several women into relationships. One of them, with a woman known as Rosa, was what Whittam termed “a consensual relationship, albeit with an undercover officer using his cover name, which was not regretted until more than a decade later when his true identity was known”.

Rosa has previously told the BBC:

‘If you put all these things together, you have a team of officers conspiring to rape’.

Boyling faced investigation for sexual offences for what he did. In addition to legal action for rape, he was subject to misconduct proceedings, and was sacked in 2018. Whittam said it’s all a heavy burden for Boyling to bear.

Is it credible that no manager knew about these relationships? Did any of them give approval? Perhaps, he speculated, there are too many for it to be possible to blame individual officers.

We shouldn’t blame them separately for the existence of what was clearly an institutionally accepted and encouraged tactic; for that, we must indeed go to the managers. But we can also certainly blame the undercover officers for perpetrating it.

Whittam mentioned the 2015 apology by the Met to some women deceived into relationships by spycops, in which it was said that such activity was ‘abusive, deceitful, manipulative and wrong’.

But, he said, spycops committing crime is essential for national security and the prevention and detection of other people committing crime. So we need to see the Met’s 2015 apology to the women ‘in context’, by which he seemed to mean it should be disregarded.

Perhaps it was justified to have a relationship to build and maintain an undercover persona, Whittam said with the air of someone who hadn’t just cited the occasion on which the Assistant Commissioner of the Met officially and bluntly declared:

‘sexual relationships between undercover police officers and members of the public should not happen. The forming of a sexual relationship by an undercover officer would never be authorised in advance nor indeed used as a tactic of a deployment… I can say as a very senior officer of the Metropolitan Police Service that I and the Metropolitan Police are committed to ensuring that this policy is followed by every officer who is deployed in an undercover role’

The accompanying written opening statement from Richard Whittam QC on behalf of Slater and Gordon Clients

David Lock QC

(Peter Francis)

David Lock QC

Peter Francis was an SDS officer from 1993-98. Like many of his colleagues, he suffered serious mental distress and PTSD after his deployment ended. He sued the Met for lack of psychological care. In 2010, he blew the whistle on spycops with an interview for the Observer. He has been a major source of evidence for researchers and journalists.

David Lock began by saying that we simply wouldn’t have the Inquiry if it weren’t for Francis. But he’s not a policy maker or politician, he’s only of use here as an ex-spycop.

Those giving evidence at the Inquiry have immunity from prosecution based on what they say at the Inquiry, but this doesn’t extend to revelations made elsewhere.

Francis has had no assurance that he won’t be prosecuted under the Official Secrets Act for what he has already revealed. Such a prosecution would leave him open to forfeiture of his pension. He is, declared Lock, hereby asking the Met Commissioner for a cast-iron assurance that he won’t be prosecuted nor have his pension removed because of past disclosures. He wants to receive this before giving evidence to the Inquiry.

On 14 March 2010 Francis began his journey of disclosure because he believes the public have a right to know what is done in their name and with their money. By 2011, the Guardian had published more articles with him using his cover name Peter Black, and in 2013 he unmasked himself. He said he came forward despite threats of prosecution, but he had some confidence that a case would not be brought against a whistle-blower acting in the public interest.

Whistle–blowing is usually of interest not just for the facts, said Lock, but for the failure of the institution to admit the truth early on. Whistle-blowers have inadequate protection, there is no support for those who do it after leaving a job, or release the info to the public domain. Francis faces the additional threat of the Official Secrets Act. Police are effectively banned from whistle-blowing, even if the facts are about public harm. The Met don’t recognise Francis as a whistle-blower, so he has no security.

Although he went public over ten years ago, and the Inquiry was set up more than five years ago, Francis hasn’t been asked to make a statement to the Inquiry, and memories are fading with time. The Inquiry is undermining itself by creating such delays. Under the current timetable, the Inquiry doesn’t intend to take evidence from Francis until 2023.

Lock continued to relay Francis’ thoughts, saying that it’s clear when Francis was undercover in the 1990s that there wasn’t proper governance or oversight to balance the needs of the police with the rights of targets. The Inquiry must decide whether this has changed much, but claims of procedural improvement must be taken with circumspection as they come from professional liars in defence of their position.

The duty of care owed to officers is routinely breached, according to Francis, because the Met doesn’t see the stress of lying and deceiving as part of one’s day job. Those who live untruths for extended periods will find themselves living in the psychological shadows.

Lock said that focus is quite rightly on victims of this barely and badly regulated activity, but dedicated spycops like Francis were badly failed by the state too. He had to resort to litigation, which was settled in 2006. He left the Met with fragile mental health having lost the real Peter Francis from living a lie for so long. There should be long term aftercare for spycops as PTSD is a long term condition.

LOOKING FOR TARGETS

Francis observed that those targeted by the SDS were supposed to be subversives seeking the undermining of the state, but this concept was conflated with the policies and convenience of the government of the day, and of economic interests.

The Vietnam War was the policy of a foreign government, yet opposition to it was seen as so subversive of the British state that the SDS was formed to counter it. None of the original target groups were proscribed. Francis believes it is never justified to spy on non-violent groups.

Such a draconian incursion into the lives of ordinary people expressing peaceable opposition to the government of the day is wholly unjustified, according to Francis. It beggars belief to allege that the Women’s Liberation Movement or Croydon Libertarians posed a threat to society.

Lock said that Francis is clear that undercover policing can destroy lives, both those of the spied upon and those of the officers themselves. It cannot be done lightly. Undercover policing is legitimate in the right circumstances, he says, but policing must be transparent and with the consent of the public.

Obviously, spycops wouldn’t be able to work if they were exposed at the time, but Francis suggests that some time after the deployment people could be told. He’s keen to be clear that he doesn’t have the expertise to speculate about timetables, but there must be a time when the state says who has been lied to and why it was justified, and be entitled to compensation if the targeting was unwarranted. Keeping the lid permanently on the box shouldn’t be an option.

It is an excellent point. The Thirty Year Rule lets us see secret Cabinet papers from 1990, yet we can’t see SDS files from 1970.

The accompanying written opening statement from David Lock QC on behalf of Peter Francis

Angus McCullough QC

(Category M Core Participants: Families of Police Officers)

Angus McCullough QC

If there was any doubt as to how deep the institutional sexism of the spycops goes, look at how they treated their own wives. Angus McCullough represents three women who were wives of SDS officers.

McCullough said the women provide unique insight into the officers and the management. The Inquiry will hear many heart rending stories of betrayal and deceit, he said. The sacrifices of the wives went beyond anything they thought they were taking on. It has shattered their lives.

Each of the women has their own story, he said, but they all felt that being police wives was woven into their identity, as part of the wider police service. They felt pride in their husbands joining Special Branch, thinking they would be keeping people safe. They believed they were supporting their husbands in the fight for the good of the country.

McCullough described how they took on the burden of secrecy and fear of reprisals. They did it without any proper support from the Met. Years later they found out their marriages were based on lies. Their husbands’ jobs, of which they had been so proud, were vehicles for the worst kind of infidelity.

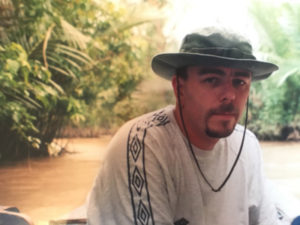

SDS Mark Jenner on holiday in Vietnam with Alison. Jenner is understood to have been in couples counselling with Alison & his wife at the same time, with both thinking they were his only partner

They saw the stress and anger that came with the spycop’s job. One had her husband tell her that they had to relocate the family at short notice, and was visited at home by manager Bob Lambert. She now doubts the necessity of this and other significant family decisions.

None had any idea that their husbands had relationships with women they spied on. All were shocked when they saw the media coverage.

Their children were born into relationships imbued with deceit. They saw them struggle with their fathers’ roles at the time, and had to help them negotiate this, then re–chart the relationships again after the publication of the awful truth. Neither the children nor the women got support.

They were an integral part of the process but also exploited by it. This is a unique position for the Inquiry. They saw close–up the impact on the officers and the lack of support. They occasionally met senior officers and have direct evidence about that and the veracity of what the managers said.

They can testify about the recruitment process into the SDS, including indications they specifically sought married men in order to ‘keep them grounded’ (i.e. outsource the stress relief and psychological care) without consideration of the damage it was likely to cause.

McCullough described how they were vetted as support for their husbands, but no support was offered to them.

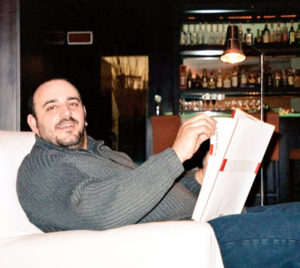

SDS officer Carlo Soracchi on holiday in Bologna with Donna McLean

They were told that their husbands were infiltrating groups of serious violent criminals. When they found out the truth about the groups that were infiltrated they were horrified about how they’d been lied to.

They suffered further with the impact of their husbands’ unsocial hours, absences and missions abroad (which they now know included holidays with the women their husbands had deceived into relationships).

McCullough said the managers promised them support, yet this never materialised. With one exception, there has been no support at all since the scandal broke. They received no warnings before stories appeared in the media, even though the Met obviously knew it was going to happen. They had no support before during or after any of it.

McCullough said the women can also testify as to frequency of contact between spycops and managers, which was basically daily and gives the lie to claims managers didn’t know what undercover officers were up to.

The women who were deceived into relationships have received an apology, but not the wives of the same officers. Why has the Met not acknowledged the sacrifice they had to make and damage to them and their families?

McCullough described the women’s anguish as they’ve been left with so many questions unanswered. How much did their support make the officers a safe bet for spycop duty? Why were they encouraged to have kids even as the stresses piled up? What support were officers offered? Was there anything else the women weren’t told about? Why were the requests for support for wives ignored? Who in the SDS knew about spycops deceiving women into relationships? Were they authorised to have those relationships? Why weren’t wives told before they were made public?

Spycops should not deceive people they spy on into relationships. Nobody should be subjected to it, nor families have to deal with it. The wives are have been dismayed by the statements from police lawyers attempting to minimise and justify the abhorrent practice.

The accompanying written opening statement from Angus McCullough QC on behalf of the Category M Core Participants

Rajiv Menon QC

(Core Participants represented by Richard Parry & Jane Deighton)

Rajiv Menon QC

Jane Deighton represents Audrey, Nathan & Richard Adams, the family of teenager Rolan Adams who was murdered by racists in February 1991 & whose campaign was one of those targeted by spycops. Jane also represents Duwayne Brooks, friend of Stephen Lawrence & prime witness to Stephen’s murder.

Richard Parry represents five targeted activists, two of whom – Tariq Ali & Ernest Tate – will supply evidence to the early phase of the hearings covering 1968-72.

Menon opened with a bold and blunt question: Why has it taken 2,065 days for the Undercover Policing Inquiry to start?

The original Chair, Lord Pitchford, hoped to finish it in 2018. Some delay is understandable as Pitchford fell ill and Sir John Mitting took over and had to get up to speed, and of course Covid hasn’t helped, but this only explains a fraction of the delay.

The main reason for the long wait, said Menon, is the police’s attempt to obfuscate, obstruct, undermine and delay. They made 148 applications for anonymity for real and cover names of spycops, they insisted every document be vetted before others involved see it. Meanwhile, some of the witnesses have died.

The applications for anonymity were not justified, said Menon. There is no evidence that officers would be at risk if they were identified – no harm has befallen any former officers, either those outed by activists, or those who have outed themselves. It is ironic that officers who invaded other people’s privacy so intensely now invoke their right to privacy at an Inquiry into their own misdeeds.

Police compounded this with mass shredding of documents. The Inquiry’s indulgence of police whims led victims to walk out of the Inquiry then processes in 2018. Little has improved since. Yet victims are still here, hoping for answers.

The Inquiry’s forerunner, ‘Operation Herne’, admitted some facts but sought to defend them and portray the problems as historic, as we might expect from a police self-investigation.

The choice is stark. Is this Inquiry also going to blame the victims and give the state a ‘get out of jail free’ card? Will it blame a few rogue officers? Or will it admit that, since 1968, the spycops have been rotten from top to bottom?

There are 219 victims who are core participants. There are surely thousands more who fit the criteria. Special thanks are due to the Undercover Research Group who have tried to list who was spied on, as neither the police nor Inquiry will publish the lists they have.

What do the victim core participants have in common? They were spied on due to direct, indirect, or perceived connection to social justice, be it against war, racism, inequality, police wrongdoing, animal cruelty, environmental destruction, the abuse of corporate power, or the exploitation of workers. Some were victimised simply for challenging a police narrative. Then we have families of children whose ID was stolen by spycops, wives of officers and a lawyer targeted.

Menon went on to list ten general points on the subject of the Inquiry.

1 – Incompatibility. Spycops’ activity is incompatible with a truly democratic society, being targeted just for having anti-establishment beliefs.

2 – Focus. The Inquiry wasn’t created by police wanting to confess, but by the work of people the police were abusing. Particularly, the women deceived into relationships, and Duwayne Brooks, Doreen Lawrence and Neville Lawrence. Also Rob Evans and Paul Lewis, whose book Undercover is a must-read on the subject. Political policing must remain the focus of the Inquiry. This wasn’t ‘serious and organised crime’.

3 – Scope. The Inquiry is about human interaction; only in England and Wales; only police not MI5. Any conclusions Inquiry reaches will this be partial and incomplete. MI5’s escape of scrutiny is alarming given that most spycops intelligence was shared with MI5 but the reverse isn’t true. Their role is essential to understand the issue.

4 – Disclosure. We must see the documents for ourselves, and in good time, if we are to properly engage. Giving Tariq Ali & Ernest Tate and their lawyers over 5,263 pages of evidence five weeks before the hearings is not good enough.

The Inquiry says it has over a million documents. How can we participate if we only belatedly see a tiny fraction of what documents are available? The Inquiry should supply all relevant documents, as in a criminal case.

With redactions, we should be told who made them – police or the Inquiry? On security or privacy grounds? Why were they needed? Some of the names of spied-on groups from 1968 were redacted. Why?

5 – Shredding. We feared spycops would do it, and they did. The Inquiry must investigate this. How can there be trust in police who have definitely shredded relevant files?

6 – Racism. The British police have always been permeated with racism at all ranks. The Macpherson Inquiry ruling of ‘institutional racism’ wasn’t news to black people, but it was the first admission from the state itself.

We’re concerned that the Chair presides alone without a diverse panel. The Chair told lawyers that Macpherson’s definition of racism is ‘controversial’. The Inquiry mustn’t reverse the progress made due to the courage of black people who’ve fought racism.

7 – Burden. The burden is on the police to explain spycops, not on the victims to justify their own actions. To dissect the politics of victims, turning the spotlight away from the police, is the politics of victim-blaming.

8 – Responsibility. The Inquiry failed to ask the state participants to supply their position in advance, so we’re only just finding out what the agencies think. Some of these opening statements have defended abuse of women by spycops by talking about undercover work against serious and organised crime. This is a red herring, spycops were never about this.

9 – Participation. After next week, the only Inquiry live-streaming is to the Chair’s home and one limited venue in London for which booking has closed. The Grenfell and Child Sexual Abuse inquiries are live-streamed – even closed hearings get streamed to the core participants, lawyers and accredited journalists via secure lines. The Inquiry’s proposed live transcription is not adequate.

Reading is not equivalent to, or even close to being equivalent to, the experience of seeing and hearing a witness give evidence, either in person or on screen. It is also impractical to expect people to read five to six hours of transcript each sitting.

This is an Inquiry with hearings shrouded in secrecy, with most of the police hidden from the public. A time delay in the streaming would avoid any wrong things being broadcast, as other Inquiries are doing.

Which non-state participants are excluded from coming to the venue to see the live-stream? Those who can’t travel; black, disabled and older people are especially at risk. This is a breach of Equalities Act obligations.

Even now, the Inquiry can set up a secure link. If the Chair can have this, why can’t others involved.

10 – Objectives. Participants want answers, chapter and verse, not just scraps. Full disclosure, seeing their full files, complete access as Stasi victims had. They want to know when they were spied on, who authorised, who else saw it?

If the Inquiry does have people’s files, why can’t the subjects even see a redacted version? If the Inquiry doesn’t have them, how can they do their job?

WHAT DO WE WANT? WHEN DO WE WANT IT?

Menon concluded his contribution for the day by saying what the people he speaks for want to see as outcomes, and why the defences we’ve heard from police representatives in the last three days should be brushed aside.

We want it publicly declared that spying on us was wrong. We want the full disbanding of the political policing units, and nothing like them to exist ever again.

Since the 1880s, Special Branch has spied on suffragettes, socialists, pacifists, anti-colonialists and more. Ideas are policed; that’s what Special Branch is there for. But in 1968 things changed, and spycops began living undercover as activists for years on end. The SDS were different from other undercovers by gathering intelligence, rather than evidence for use in trials, so their activities went without scrutiny for decades. The SDS was never about detecting crime, but spying on political opponents of the status quo.

The SDS had a clear political orientation to the right of the spectrum. Officers were politically vetted. Targets were initially all on the left. This was secret, anti-democratic political policing. Only in the late 1970s did a couple of far-right groups attract attention.

There appear to have been no safeguards to check if this spying was justified, necessary or proportional, or its methods ethical or lawful. It was given free rein, regardless of norms and values.

Today, the 70th anniversary of the signing of the European Convention on Human Rights, police lawyers are telling the Inquiry ‘don’t judge 1968 by our standards’, as if people in the 60s didn’t care about human rights and liberty.

We have a host of regulations and supposed oversight bodies. So are spycops’ excesses a thing of the past? It would be extremely naive to assume the police have learned and moved on. Note the reluctance of Counsel for the Met to answer Inquiry’s questions about current policing yesterday: The CHIS Bill demolishes our belief in the effectiveness of oversight, placing no limits on state agents from committing crime, and bars victims from seeking legal redress.

Rajiv Menon will conclude his statement on the morning of 5 November.

The accompanying written opening statement from Rajiv Menon QC on behalf of the Core Participants represented by Richard Parry and Jane Deighton

COPS will be live-tweeting all the Inquiry hearings, and producing daily reports like this one for the blog. They will be indexed on our UCPI Public Inquiry page.