Tranche 1, Phase 2, Day 9

4 May 2021

Summary of evidence:

‘Bob Stubbs’ (HN301, 1971-76)

Introduction of associated documents:

‘Peter Collins’ (HN303, 1973-77)

Evidence from witnesses:

‘Mike Scott’ (HN298, 1971-76)

‘Mary’

‘Bob Stubbs’ (HN301, 1971-76)

Summary of evidence

‘Bob Stubbs’ (HN301, 1971-76) was deployed late 1971 to May 1976. His main target was the International Socialists, but he also targeted the main Irish political campaigns of the time. Though still alive, the Inquiry has chosen not to call him to give evidence, instead reading out a summary of his statement

The Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) officer joined Special Branch in 1970/71, considering it an ‘elite unit’. He was recruited to the SDS soon after. There was no formal training, and he picked up all he needed from his three months in the back office.

He says he was given ‘free rein’ to direct his own tasking:

‘I understood that the SDS’s function was to gather information about groups that posed a threat of public disorder and violence. That said, the SDS gradually morphed into more of a general intelligence-gathering unit.’

Once in the field, he visited the SDS safe house 2-3 times a week. Initially this was an informal arrangement, but by the end of his deployment it had become a requirement. All field officers were expected to attend on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays to meet with SDS managers from the New Scotland Yard office.

From the large gaps in dates on the reports in the Inquiry’s possession, it’s clear that a proportion of his reporting is missing. Stubbs himself specifically notes the absence of his reporting on small demonstrations – such as industrial pickets.

COVER EMPLOYMENT & THE PALESTINE SOLIDARITY CAMPAIGN

Stubbs believes that he was chosen in part due to his dark complexion, which may have assisted him to infiltrate groups focusing on Middle Eastern politics. This was a time when Palestinian hijackings were of significant concern.

His first task was to befriend a leading activist in the Palestine Solidarity Campaign – then a coalition of left groups from the Young Liberals to the International Marxist Group, and unconnected with armed groups.

He obtained a job as a laboratory technician at Guys and St Thomas’ Hospital where this activist also worked. It was a full-time job but after a couple of months he had failed to strike up the friendship with his target and so the attempt was abandoned.

MAIN TARGET – INTERNATIONAL SOCIALISTS

He then switched to the International Socialists (later the Socialist Workers Party), joining its Hammersmith & Fulham Branch. He subsequently moved on to the Wandsworth & Battersea branch and finally the Paddington branch in late 1975.

Stubbs believes that the International Socialists were principally of interest to the SDS because of the possibility of public disorder and violence, particularly during anti-fascist counter protests.

He acted as treasurer for both the Paddington branch [UCPI0000009537] and perhaps also the Hammersmith & Fulham branch. In his statement he recalls being told at the beginning of his deployment that the SDS encouraged field officers to take on a position in activist groups that would give them access to membership information.

Stubbs says he was on friendly terms with activists and would on occasion have a drink with others following a meeting. However, he says he did not form any close relationships.

In March 1973, Stubbs produced a report on the IS national conference [UCPI0000007905]. The political committee recommended that IS form factory branches and challenge the communist leadership of industrial action from the shop floor.

In April 1974, Stubbs fed back intelligence on the formation of an IS Lawyers Group, [UCPI0000007915], which aimed to provide legal advice to any member (or trade unionist) ‘who clashes with the law on pickets, marches and demonstrations’. In March 1975, [UCPI0000006921], he noted the intention of the IS to stand a candidate in the Walsall by-election.

As with many undercovers of that era, Stubbs reported on anti-fascist activity. On 6 September 1975, members of the South West London District of IS, with which Stubbs was associated, were in the ‘vanguard’ of IS members who attempted to disrupt a march by the National Front in Bethnal Green [UCPI0000007566].

RED LION SQUARE

During the course of his deployment, Stubbs witnessed public disorder and violence during demonstrations involving IS and the National Front. In particular he was was at clashes in both Leicester, and in Red Lion Square in London – the latter being the anti-fascist demonstration where Kevin Gately was killed by the police.

At this event, Stubbs says he was punched by a police officer, joining a growing list of undercover officers who were assaulted by their uniformed colleagues.

Given that police and the Scarman Inquiry blamed the death on the protestors, the fact an undercover was subject to police violence at the protest is significant. It is one of the reasons why non State core participants would have liked the undercover to give evidence.

ANTI-INTERNMENT LEAGUE (AIL)

He used his membership of IS to report on meetings of Irish political groups, particular the Anti-Internment League (AIL), which campaigned to stop the imprisonment without trial of republicans in Northern Ireland.

Whilst not directly tasked to attend meetings of the AIL, as its activities were related to the Troubles they were of automatic interest. He does not recall the AIL posing a threat of public disorder, but suspects that some members approved of the use of violence as a political tool, and of the activities of the Provisional IRA.

His reporting include AIL conferences where support for both Provisional and Official IRA was apparently voiced, and which delegates from Sinn Fein and Clann na h Éireann attended.

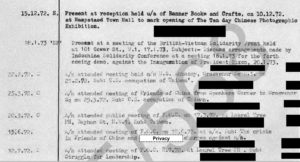

Other examples of his reporting include a 1972 AIL delegate meeting [MPS-0728874], where he records the detailed knowledge that one activist present, Géry Lawless, had of the alleged route to be taken by the Irish Prime Minister on his visit to the UK.

Stubbs and officer HN338 produced a joint report on the ‘Police oppression and victimisation’ conference [UCPI0000015700] organised in response to police raids on Irish homes in Coventry.

TROOPS OUT MOVEMENT – WEST LONDON BRANCH

Stubbs also reported on the later Troops Out Movement, which called for British troops to be withdrawn from Northern Ireland. In particular, he attended meetings and reported on the West London branch, which was possibly the first of the TOM groups.

His earliest report about the TOM is dated 12 November 1973 [UCPI0000009938]. He cannot recall any violence, criminality, or public disorder involving TOM members. Rather, he presumes the SDS interest in TOM was due to a supposed connection to ‘Irish extremism’.

NICRA

Several of Stubbs’ reports related to the West London branch of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association. He does not recall reporting on the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association (NICRA) but accepts that he must have done because there are reports in his name [MPS-0737808] regarding the group’s activities.

BELFAST TEN DEFENCE CAMPAIGN

He also seems to have had access to the Belfast Ten Defence Committee with a report of 2 December 1974 [UCPI0000015115] referring to a Committee member opening a Coop bank account for the group. The Belfast Ten had been accused of carrying out IRA bombings in London in March 1973 and held on remand, leading to a campaign for their release.

VISIT FROM THE COMMISSIONER

Stubbs recalls Sir Robert Mark, the Met Commissioner, on one occasion making a surprise visit to the SDS flat in North West London.

Bob Stubbs’ deployment came to an end in May 1976, after approximately five years, which was considered an optimal length, as he commented:

‘five years would allow time for officers to become comfortable in their role and get to know activists, but it was not such a long period that they would then find it hard to transition back to their normal lives.’

He denies any involvement in criminal activity, sexual relationships, or any kind of legal proceedings. He also stated that he never joined a trade union.

Written Statement of Bob Stubbs

‘Peter Collins’ (HN303, 1973-77)

Introduction of associated documents

Vanessa & Corin Redgrave

‘Peter Collins‘ (HN303, 1973-77) infiltrated the Workers Revolutionary Party (WRP) from 1974 to 1977. He was asked by them to in turn infiltrate the National Front, remarkably something SDS management agreed to.

The officer is allegedly far too ill to submit a written statement, however the Inquiry highlighted reports relating to his deployment in an appendix to its opening statement.

The WRP was a Trotskyist organisation, led by someone called Gerry Healy for many years, receiving public attention due to the involvement of actress Vanessa Redgrave and her brother Corin.

It grew to a sizeable organisation with wide reach in the 1970s. Collins’ reports discuss the size of the organisation’s membership and the circulation of their newspaper, as a report on a 1975 delegate conference demonstrated [UCPI0000022002].

The same report also describes the revolutionary intent of the WRP as seen through Collins’ reporting, in which he quotes Vanessa Redgrave as telling conference that:

‘the ruling class knows that civil war is on the agenda…the time for class compromise is over; the struggle can only be resolved by force.’

Collins’ own focus seems to have been branches in North London.

POLICE RAID ON THE RED HOUSE

In the summer of 1975, Corin Redgrave purchased the White Meadows Villa in Parwich, Derbyshire, which became the WRP Education Centre. Shortly after its opening in September 1975, it was raided by police and some old bullets were found in a cupboard. The WRP’s reaction to this raid was reported by the SDS [UCPI0000009265].

A report dated 4 February 1976, [UCPI0000012240], compiled by Collins after he had attended an educational event at the Centre, details the extensive security arrangements in place there and the purported discovery of listening devices at the Centre following the police raid.

In correspondence between senior Special Branch management [MPS-0741115], Commander Rollo Watts noted:

‘It is valuable for us to learn that, despite all the speculation, the courses at ‘White Meadows’ do not include incitement to public disorder.’

Earlier, in May 1974, Collins had reported [UCPI0000009964] on measures to be taken by the WRP to combat police spies and informants and any other ’spies and agent provocateurs’ who might try to steer them away from their revolutionary Party-building and towards the kind of ‘popular-front’ actions which may expose the WRP to ’police persecution and ridicule in the capitalist press’.

As a counterpoint to the raid, the Inquiry also pointed out that although the WRP was involved with the Free George Davis Campaign, it actively sought to avoid being associated with criminal acts, [UCPI0000009410]. Davis had been jailed for bank robbery and become a cause célèbre over irregularities in the prosecution evidence.

As some point in 1975, ‘Michael Scott’ (HN298, 1971-76) began reporting on the WRP, so the authorship of some SDS reports on the group is unclear.

MI5 INTEREST

It is notable some of the SDS reports regarding the WRP are in response to Security Service (MI5) requests for information. This includes a March 1975 report [UCPI0000006993] where MI5 asked to clarify what was meant by the term ‘sleeping WRP members’.

WRP TRADE UNION ACTIVITY

Collins’ reporting on the WRP regularly referred to the WRP’s associations with trade unions. These included the Union of Construction, Allied Trades and Technicians (UCATT) and the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) – both Core Participants in this Inquiry.

A March 1975 report [UCPI0000006909] details a Conway Hall meeting of the WRP’s Builders Section.

A report dated 24 March 1975 [UCPI0000006961] gives information about a march from Hull to Liverpool organised by the Wigan Builders Action Committee in support of the Shrewsbury Two, and claims the route was chosen to put pressure on National Union of Mineworkers’ leader Arthur Scargill to support the campaign.

SHREWSBURY TWO

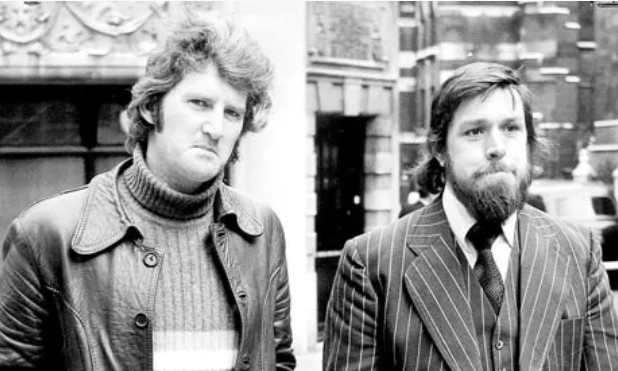

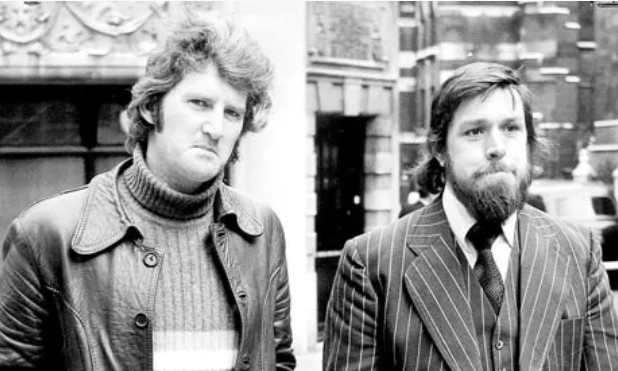

Des Warren & Ricky Tomlinson, the ‘Shrewsbury 2’

There are two reports which reference the Shrewsbury Two – Ricky Tomlinson and Des Warren – who were framed and jailed for ‘conspiracy to intimidate’ for their part in protesting to improve working conditions for builders during the industry’s national strike in 1972.

After nearly 50 years, their convictions were overturned earlier this year. There are two reports, [UCPI0000012752] and [UCPI0000012781], which detail the meeting of the Shrewsbury Two Action Committee organised by the WRP at the Adelphi Hotel in Liverpool on 29 July 1975. This was attended by hundreds of people, including coachloads from London.

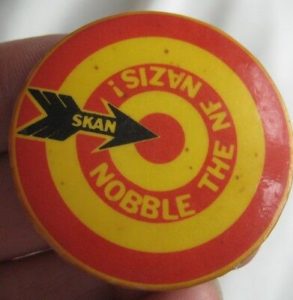

REPORTING ON THE NATIONAL FRONT – ON BEHALF OF THE WRP

In 1975, not knowing their member was a spycop, the WRP asked Collins to infiltrate the National Front (NF), and a small offshoot of them, called the Legion of St George. This was cleared by his SDS managers, so he reported on them to the SDS for several months, until he left the field altogether [MPS-0728980].

It worth noting the two rather different assessments of Collins’ far-right infiltration contained in the SDS annual reports.

The 1975 report [MPS-0730099] mentions it in positive terms – boasting that Collins is now acting as a double agent, and leading a ‘triple life’.

However the 1976 report [MPS-0728980] noted that the NF was no longer of interest to the SDS as ‘the information gained added nothing of real value to that obtainable from already excellent Special Branch sources’ It was not considered worth placing another SDS officer into the NF after Collins’ deployment ended.

The four reports that the Inquiry has published of Collins reporting on the far-right are: [UCPI0000006931], [UCPI0000012751], [UCPI0000009480] and [UCPI0000009553].

PUBLIC ORDER DISCUSSION

In November 1977, Collins and another undercover, Barry/ Desmond Loader (HN13, 1975-78), were taken to meet Deputy Assistant Commissioner David Helm. He oversaw public order policing for the Metropolitan police.

They talked about the perspectives of those on the ground and the changes needed within the police following such events as the street violence during the confrontation between fascists and anti-fascists at the 1977 ‘Battle of Lewisham’ and the Grunwick Strike, [MPS-0732885] and [MPS-0732886], – indicating the presence of undercovers at these events.

‘Mike Scott’ (HN298, 1971-76)

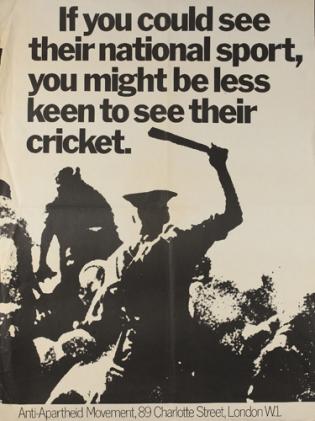

‘Mike Scott’ (HN298, deployed 1971-1976) is the cover name used by a former Special Demonstration Squad undercover officer who – according to the Inquiry – infiltrated the Young Liberals, Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM) and Workers Revolutionary Party (WRP) from 1971 to 1976.

‘Mike Scott’ (HN298, deployed 1971-1976) is the cover name used by a former Special Demonstration Squad undercover officer who – according to the Inquiry – infiltrated the Young Liberals, Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM) and Workers Revolutionary Party (WRP) from 1971 to 1976.

In the Inquiry, he is also known at HN298, his real name is protected. He stole the identity of a living person, Michael Peter Scott, as his cover name.

His evidence is among the most remarkable of the former undercovers heard to date, covering a clear miscarriage of justice among anti-apartheid campaigners, the theft of an identity from a living person with a callous lack of concern over the impact it could have had, and the gratuitous physical assault on a campaigner who had rightfully identified him as an undercover – something he dismissed as not really a crime.

From evidence given by Jonathan Rosenhead and Christabel Gurney on Thursday last week, it is clear that he had infiltrated the Stop The Seventy Tour, a different anti-apartheid group, rather than the AAM.

Crucially, in May 1972, Rosenhead, Gurney and ‘Scott’ were arrested with 11 others for taking part in a direct action to prevent the British Lions rugby team from leaving for a tour of apartheid South Africa. As part of a wider campaign for a sports boycott against the apartheid state, they blocked a coach carrying the British Lions team as it was about to leave a Surrey hotel for the airport.

A press report from the time recorded that he had told the court that his name was Scott and that he lived in Wetherby Gardens, Earls Court, West London. This was the address of his cover flat (at number 16). Scott was convicted of obstructing the highway and obstructing a police officer. He was fined and given a conditional discharge. Rosenhead and Gurney were also fined.

Scott’s superiors authorised him to use his fake identity in the criminal trial and to be convicted under his alias. The Inquiry is also investigating if the conviction became a criminal record attached to the real Michael Peter Scott.

In their opening statement, the Counsel to Inquiry stated:

‘Indeed it appears that senior management encouraged his participation in the criminal proceedings in the full knowledge that he would attend meetings to discuss trial tactics, but there seems little appreciation by senior management either that these meetings may be subject to legal professional privilege or that his participation in criminal proceedings as a police officer in a covert identity raised any legal or ethical considerations.’

This deceiving of a court potentially provides sufficient grounds for the activists to have their convictions overturned, something Rosenhead is considering.

Groups he targeted included:

- Putney branch of Young Liberals – early 1972 to mid-1974

- Commitment and the Croydon Libertarians – early 1972 to mid-1973

- Irish Solidarity Campaign – mid 1972 to September 1972

- Anti-Internment League – September 1972 to late 1973

- Workers Revolutionary Party – Spring 1975 to April 1976

JOINING THE SPYCOPS

Scott had worked in the Metropolitan Police Special Branch’s ‘C Squad’, which monitored communists. Reporting on these meetings gave him a good idea of what kind of information Special Branch was interested in.

The existence of the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) was well known within C Squad and their offices were close to each other inside New Scotland Yard.

Scott says he actively sought out the role. He does not remember any formal interview process, but does recall starting to grow his hair and beard on hearing that he was likely to be accepted into the unit.

He didn’t receive formal training and doesn’t recall any informal advice either – whether about guidance around being arrested and going to court in his undercover identity, or avoiding legally privileged conversations, though these were all issues that played a part in his deployment.

The SDS was ostensibly tasked to gather intelligence on subversion and threats to public order. Asked to define subversion, Scott replied:

‘Well, subversion is when you would do or carry out acts that would endanger the well-being of the State’.

He was clear that he felt this meant anything that would upset whoever happened to be in power at the time:

‘The government of the day, whoever they are, is elected and so therefore they have a right to be there and govern. And so therefore, anything that was likely to endanger that proper democratic situation would be subversive.’

Admitting the SDS cast a wide net, he said:

‘Most groups were not subversive but some of course had a potential to be, and that’s what we were reporting on.’

IDENTITY THEFT

As his previous Special Branch work had made him familiar with researching the background of ‘persons of interest’, Scott was familiar with the government birth registry records at Somerset House. When asked to come up with a fake identity, he went there and located a birth certificate for someone whose name and date of birth were similar to his own.

Asked if he did any assessment of the risks of stealing the identity of a living person, Scott gave an answer that implied yes, but actually means no:

‘I did an instant risk assessment, and that was that there wasn’t any risk.’

As to whether he thought there could be ill effects from having a criminal record applied to the real Michael Peter Scott, he brushed the concern aside:

‘What happened to me was not exactly a criminal record, it was really of no consequence, actually.’

In fact, it was exactly a criminal record.

There could be circumstances where he might break the law, with the permission of superiors. This is not something he’d expect to do – ‘you’re a police officer, after all’ – but says he was given no instructions or guidance, it was just left to ‘common sense’. He said that approach applied to all aspects of the job:

‘you were left to get on with it, but that was no bad thing. To have a big rigmarole about what you should do and what you shouldn’t do would be, I suppose, limiting the intelligence of your officers.’

He used Michael Scott’s birth certificate, and had a driving licence, bank account and other registration documents in the name. He thought this may, if anything, be positive for the real person:

‘It might assist him because my credit record was good.’

This quote typified the cavalier approach Scott throughout his evidence took with regard to the potential impact on the person whose identity he stole. This is seen again when the impact of his conviction in the identity of Mike Scott is covered (see below).

TASKING

Scott states that he was never tasked to infiltrate any particular group, Instead, he decided for himself which meetings and organisations would yield information of interest to Special Branch. To do this, he simply looked out for anything that would involve demonstrations, causing nuisance, or acting contrary to the law.

All the groups he and his colleagues targeted were on the left of the political spectrum:

‘There weren’t any right-wing groups who were demonstrating, or causing any problems as far as I can recall, at the time.’

Scott’s method was meandering. There was no master plan to use one group to get the credibility for a later target. He said it didn’t matter if officers duplicated one another’s work by infiltrating the same group.

Prompted by the Inquiry, he said he never discussed with management whether a group actually warranted infiltration.

MEETING AT THE SAFE HOUSE

Scott was asked about his reports and the weekly get-togethers at the SDS safe house where managers would check in and take information. His memory there was scant.

All the officers would meet there at the same time, around a dozen of them in one living room. He recalled there was high quality food and drink, as it would be ‘a fairly social occasion… it wasn’t all business’.

And yet, having gone to several hundred such meetings with a rarely-changing group, Scott does not remember the undercover discussing their deployments with one another. He claimed they didn’t discuss politics or anything else that affected their work, not even if they were likely to be at the same upcoming event.

He does remember chatting about toy lead soldiers, and claiming expenses though.

When this point was examined, he conceded that he ‘felt quite friendly with’ a few colleagues. When asked to list which ones, he only specified ‘David Hughes’ (HN299/342, 1971-76)

Scott’s skill for drawing blanks extended to his knowledge of colleagues deceiving women into sexual relationships.

Asked specifically whether Richard Clark (‘Rick Gibson’ HN297, 1974-76), who deceived at least four women into relationships, had, as a colleague described, ‘a reputation as a ladies’ man’, Scott said he knew nothing about it.

He also refuted allegations by a colleague that there was banter at the safe house meetings about sexual relationships. If such things had occurred they would not have been spoken about, he explained:

‘It’s a private thing and that’s a matter for them.’

The spycops were visited by very senior officers. Scott remembers the then-Commissioner Sir Robert Mark visited the safe house, and on another occasion Deputy Assistant Commissioner Vic Gilbert.

STARTING SPYING

Early in his deployment, Scott spied on the Spartacus League, which he described as a ‘revolutionary group’. He doesn’t remember them organising any demonstrations, though.

The Inquiry showed a July 1971 report by Scott [MPS-0732350] on a public meeting of the South West Spartacus League. One of the items mentioned was a ‘Revolutionary Training Camp’ – a week-long event under canvas in the New Forest.

When it was suggested this seemed more about public speaking and political teaching than armed revolution, Scott explained it was still of interest to Special Branch:

‘Because obviously armed insurrection starts somewhere. It starts with things like that.’

From there, Scott moved to the Enfield branch of International Socialists (IS), which later became the Socialist Workers Party.

He admitted that IS demonstrations were expected to be orderly, but certain individuals might come along and make them disorderly.

‘Revolution begins with groups like the International Socialists and there has to be some roughing up of the system in order to get on the road to revolution… I don’t think anyone was far down the road to revolution in 1971, but there was plenty of activity.’

In a wry move, Counsel confirmed that revolutionary groups would be of interest to the SDS, and turned to Scott’s infiltration of Putney Young Liberals. This lasted for at least half his deployment, with the Inquiry publishing Scott’s reports between January 1972 and August 1974.

PUTNEY YOUNG LIBERALS

Young Liberals, the youth wing of the Liberal Party (which later merged into the Liberal Democrats), was engaged in the same kind of civil rights and environmental issues that concerned the Party at large. The Putney branch meetings were usually 10-20 people, held at the home of Peter Hain, who gave evidence to the Inquiry last Friday.

Did Scott’s managers have any qualms about spying on a mainstream political party?

‘It wouldn’t have mattered what party they were from. If they were demonstrating and perhaps making a nuisance of themselves, they would have been reported on.’

The Putney branch of the Young Liberals was targeted because it included the Hain family.

In another of his explanations that start off as a denial and end up with an admission, Scott said:

‘It wasn’t the fact of Peter Hain being there. I think he was the president of the Young Liberals at the time. But in any event, much of this activity against South African rugby teams or the cricket teams were because of him. His family were very opposed to apartheid. Not just him, his parents as well, and that was the focus.’

DON’T TELL PARLIAMENT

Scott suspects managers may have thought spying on a mainstream party was risky to their reputation:

‘well of course such things, if it were to flare up, they could make a lot of fuss about it in the Houses of Parliament and people would be then worried about their jobs and, you know, it filters down.’

It’s an extraordinary admission. To say that, if the government of the day found out what he did, then his managers would have been sacked. It contrasts with his earlier claim that the SDS existed to uphold the wishes of the government of the day.

Continuing on the infiltration of Putney Young Liberals, Scott averred he was just ‘an observer’ at meetings. The Inquiry, however, showed report [UCPI0000008240] from January 1972. It’s the minutes of the Putney branch of the Young Liberals at which, of the 14 attendees, Scott was elected as the group’s Membership Secretary.

Two of the others present were Peter Hain’s younger sisters Jo-Ann and Sally, who were under 18. Scott said he didn’t remember them being there, and didn’t remember being Membership Secretary, and in fact even though he’s the credited author he may not have even written the report.

‘I’ve got no recollection at all of Jo-Ann Hain or Sally Hain or any children at any meetings because they’re of course of no relevance’.

In perhaps his most extraordinary denial-admission U-turn of the day, he went on:

‘As has been shown by the green movement, there are young ladies of tender age that can be quite significant, and so I would have possibly put them down anyway if they were in attendance’

HIGH STREET SUBVERSION

Another report on the Young Liberals [UCPI0000008254] of April 1972, describes discussion of the traffic on Putney High Street. There was mention of direct action to close the High Street, and support from a member of the Putney Society are recorded.

Scott defended his reporting by spreading the SDS’s remit to anything that might be of interest to any area of policing:

‘they were talking about closing the roads, closing the High Street. That clearly is of interest to the police. That’s it. The SDS is part of the police… I think the activities of the SDS were well-directed, and I think it was money well spent.’

CENTRE-LEFT EXTREMISTS

The Young Liberals’ 1972 annual conference was the subject of the next report [UCPI0000008255] shown by the Inquiry.

In it, Peter Hain is described as being ‘centre-left’. This report is from a unit who, according to one of its Annual Reports during Scott’s deployment:

‘concentrated on gathering intelligence about the activities of those extremists whose political views are to the left of the Communist Party of Great Britain’

There are some extremely distasteful details in this report – including a mention of the ‘Blagdon amateur rapist’, a comment Scott described as ‘amusing’.

There are details about MP David Steel’s attendance at the conference. Under the Wilson Doctrine, no MP should be subject to state surveillance (this has more recently been amended to it being permissible with authorisation from the prime minister).

Scott said his managers didn’t even remark on his breach of protocol:

‘MPs are not above the law and so in the context of the reporting no, no comment was made’

During Steel’s speech, paper planes were thrown at the stage by members of a libertarian group called Commitment. Scott attended Commitment meetings (see below), ‘as they seemed to be the ones likely to cause trouble’.

The Inquiry asked whether he meant more throwing of paper planes.

‘I expected that they could be more serious than that… none of these people, in the end, turned out to be very serious.’

Scott was asked why he reported [UCPI0000008248] the details of the red Volkswagen used by Peter Hain and his secretary in February 1972:

‘he was a person of interest and therefore it makes sense to note the vehicles such people are using.’

DEATH ON THE STREETS

The next report [UCPI0000008269] is on a Young Liberals Council meeting held in Birmingham in June 1974.

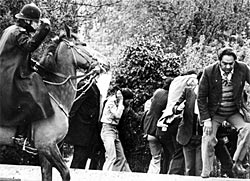

The meeting passed a motion expressing deep regret for the recent death of Kevin Gately at an anti-fascist demonstration in Red Lion Square, London, and called for a public inquiry into the way the police had handled this demonstration and the events that led to Gately’s death.

It was the first time anyone had been killed at a demonstration in England for years. The right-wing National Front were meeting nearby, and the anti-fascist counter demonstration was repeatedly charged by police, including mounted officers swinging truncheons.

At 6’ 9” tall, Gately’s head was well above the level of the crowd. He was found after a police charge, having been struck on the head. It was a major political event of the time. Scott says he has no memory of it at all.

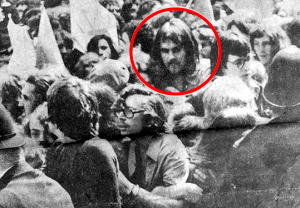

Kevin Gately (circled), anti-fascist demonstration, London, 15 June 1974

Scott’s report records that the meeting Young Liberals Council:

‘condemns the vicious & unnecessary attack on the left wing demonstrators by the police and blatant bias shown by the police in favour of the march organised by the National Front’

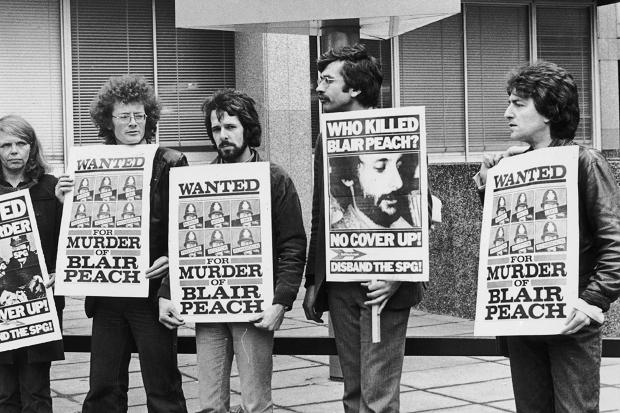

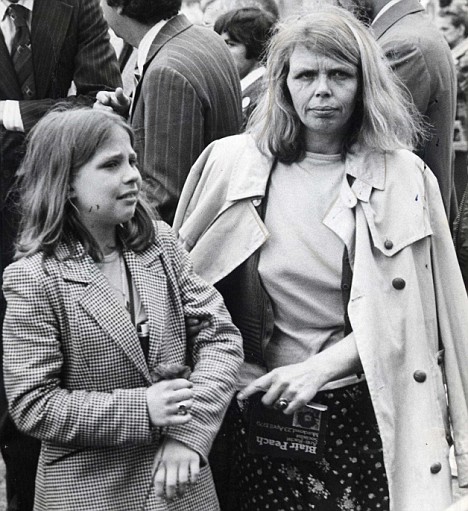

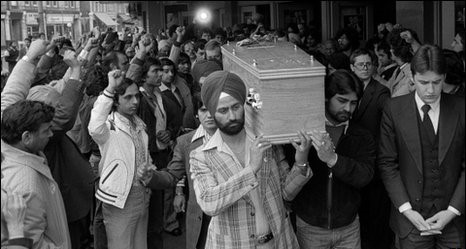

It also asked the Home Secretary to commission a public inquiry and disband the Met’s notoriously violent Special Patrol Group (who five years later went on to kill another anti-fascist, Blair Peach, during another counter-demonstration against the National Front).

Scott said that ‘you need as much information as you can glean’ if you’re allocating resources for forthcoming demonstrations. But, it was pointed out, this is not about any future event, it’s a political party asking for an inquiry into a past event, within the democratic process.

Asked if the Young Liberals were targeted because they were involved in anti-apartheid campaigning, Scott confirmed that the protests at sports matches by all-white teams from apartheid South Africa were scenes of public disorder.

Why would a self-tasking undercover like Scott not choose to spy on the far right?

‘Well, as far as I know, there weren’t any problems with the far right. I guess you mean the National Front… I wasn’t aware of too many demonstrations organised by them’

COMMITMENT

Commitment was a small libertarian anarchist group who met in South London who Scott said wanted ‘to irritate and inconvenience some large companies’. Meetings were usually 6-8 people.

In March 1972, Scott reported [UCPI0000008560] on them and their objection to Rio Tinto Zinc mining in Snowdonia National Park.

He cannot recall Commitment being involved in any public disorder or criminal offences. So why infiltrate them at all? His explanation, once again, ended up opposing where it began:

‘potentially they could cause chaos in the streets. The fact that they didn’t was probably lack of organisation rather than a will to do so… because clearly if you can speak about it you can carry it out.’

Scott also infiltrated Croydon Libertarians, whose membership overlapped with Commitment. One of his reports [UCPI0000008152] from April 1973 describes how Croydon Libertarians used a length of chain to block a road as part of a campaign to create a pedestrian precinct. The chain only stayed in place for five minutes or so, to the consternation of the group. It seems clear that Scott was responsible for this rapid removal.

He said the group was no threat to public safety:

‘it was on this kind of level, no one was thinking of doing anything that was too dangerous or dramatic, it was this kind of level of stuff’

STAR & GARTER ARRESTS

On 12 May 1972, protesters blockaded the Star & Garter Hotel, Richmond, in order to prevent the British Lions rugby team leaving for the airport to go on a tour of apartheid South Africa.

A report [MPS-526782] from 16 May 1972 describes a planning meeting of around 20 people at the house of Ernest Rodker. The activists planned for look-outs – those who kept an eye on the movements of the rugby players – and for cars and deliveries of skips that could be used to block the coach from leaving the hotel.

There was a discussion of methods for signalling to each other. The report includes a story of Jonathan Rosenhead offering flares for this purpose, and later lighting one in the car-park. Rosenhead told the Inquiry last week that he has never handled a flare in his life.

Asked of he might be mistaken, Scott was adamant:

‘If I’ve written the report that said that he did it then he would have done it.’

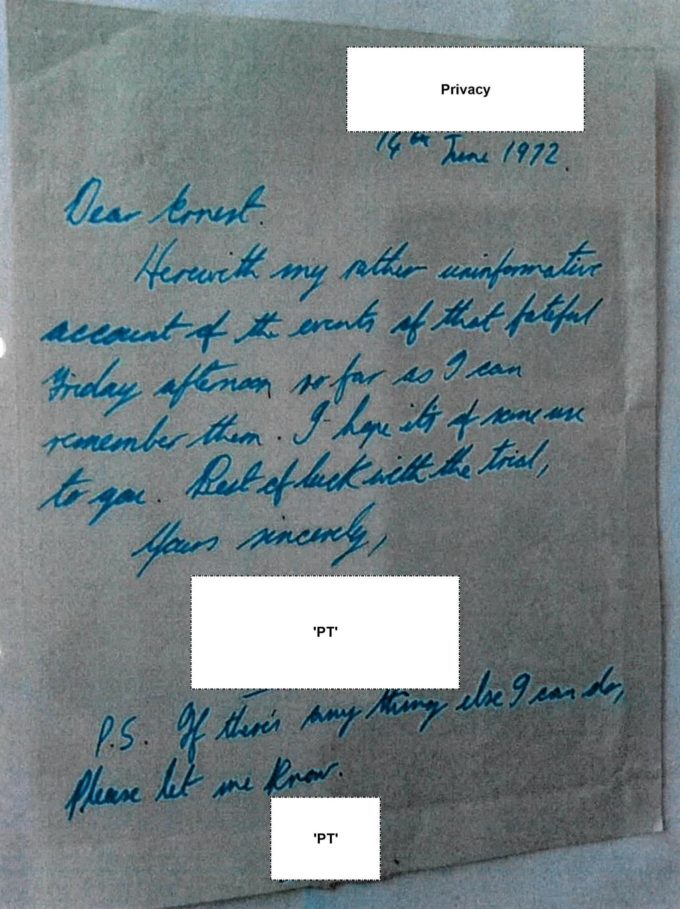

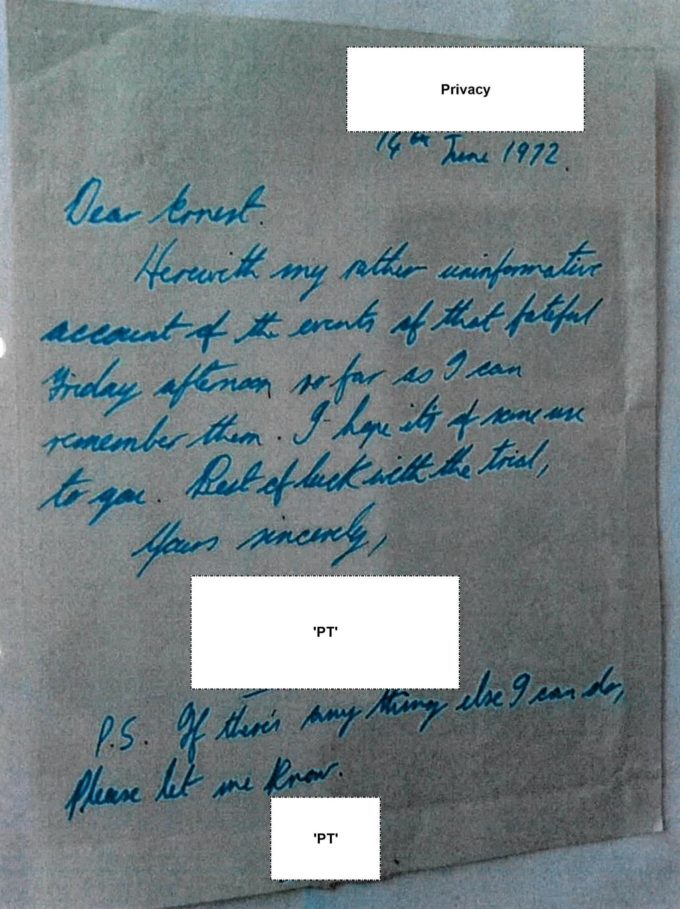

Letter from PT to Ernest Rodker, 14 June 1972

A Special Branch report [MPS-0737087], from the day after the action, tells of activists sitting down to block the British Lions rugby team bus, saying as each small group was arrested, another group would replace them.

Ernest Rodker in his evidence provided at handwritten letter [UCPI0000033628] from a witness to the action. In it, Scott is described as still present after most people had been arrested, and being with a woman who was trying to stop the police from moving a red Mini blocking the entrance.

Scott was one of 14 people arrested that day. His report included comments from the activists’ lawyers – these have been redacted from the documents released by the Inquiry as even now, 50 years later, they are subject to legal privilege. And yet they were put in a report to the prosecution side from a spy among the defendants!

He confirmed that he was present at meetings of the defendants and their lawyers.

The group was summonsed to appear at Magistrates Court on 14 May 1972. All the defendants pled Not Guilty and were bailed to return to court in June.

POLICE PLEASED WITH THEIR CRIME

He did not inform anyone at the court that ‘Michael Scott’ was not his real name. He was not told of anyone else doing so.

Scott had earlier told the Inquiry he did not recall ever seeing the 1969 Home Office circular document on informants who take part in crime, which expressly forbade any course of action that was likely to mislead a court.

After that first court appearance, a report [MPS-0526782] shows Deputy Assistant Commissioner Ferguson Smith also declaring himself happy to ignore Home Office protocol and continue with this subversion of the judicial system:

‘Faced with an awkward dilemma for so young an officer, I feel that DC [redacted] acted with refreshing initiative, as a result of which he must now have both feet inside the door of this group of anarchist-oriented extremists under the control and direction of Ernest Rodker. This man has been a thorn in the flesh for several years now, having had no fewer than 14 court appearances prior to 1963 for offences involving public disorder.’

Ferguson Smith is none other than the officer who oversaw Conrad Dixon’s founding of the SDS in 1968.

Arrest of undercover officers was dismissed as:

‘merely as one of the hazards associated with the valuable type of work he is doing. there is absolutely no criticism of the officer’

The memo said that the Assistant Commissioner (Crime), one of the most senior officers in the Met, had been informed. There can be no longer be any doubt that the SDS’s activities were known and approved at the highest levels of the Met.

According to another report by Scott [MPS-0737109], 13 people attended a meeting at Jonathan Rosenhead’s home on 21 May 1972 which included some discussion on legal strategy in the case – which is reported back. Scott does not recall any discussions with the unit’s managers about this legal case.

A further report by Scott [MPS-0737108] includes advice given to the group of defendants by their lawyer Ben Birnberg. Again, he has no recollection of the managers commenting on this.

Along with the others, Scott was found guilty (of obstructing both the highway and the police) and was fined. He thinks he would have claimed this under his spycops expenses.

CRIMINALISING THE REAL MICHAEL SCOTT

Scott was convicted under the identity of a real person. Asked if possible repercussions on the real Michael Scott bothered him, he was unruffled:

‘It was such a low key thing that it wouldn’t matter who you were. If you had been convicted of such a thing it would mean very little really.’

If the conviction didn’t belong to the real Michael Scott, did the spycop who stole the identity consider himself as a person with a criminal record, did he declare it if he was asked about previous convictions?

‘No, I didn’t. I never gave it another thought really.’

WEST CROSS ACTION GROUP

Scott also infiltrated the West Cross Action Group (WCAG), which opposed proposed construction of an urban motorway.

‘I suppose it’s like anyone that is protesting about a road. There’s the possibility that they would do something to stop it happening, and that’s of interest to the police.’

The reason this particular group was infiltrated became clear when we saw a report [UCPI0000008258] describing a meeting that was convened by Peter Hain and held at his home.

The next WCAG meeting report [UCPI0000008260] is from a different campaigner’s home. According to the report, Hain suggested some form of direct action should be incorporated into the campaign and suggested painting the roads at the points where the motorway would cross existing avenues might be a good idea.

Scott admitted WCAG did not cause disorder, paint roads, nor any other crime. So, were they seeking to overthrow parliamentary democracy?

‘They may well have been. They may well. But I don’t think so.’

And yet, Scott infiltrated the group, attended the meetings, and his reports were copied to the Security Service (MI5).

‘Well it wasn’t all about overthrowing democracy, it was about nuisance value and the fact that they caused problems and possibly danger to the public by their actions and therefore this is the role of the police. This is what we have police for, to look after us’.

IRISH SOLIDARITY CAMPAIGN

There are reports by Scott on the Irish Solidarity Campaign (ISC) for a short period in 1972, following in the wake of Bloody Sunday.

On 30 January 1972, British soldiers in Derry opened fire on a march protesting against internment without trial in Northern Ireland. 26 civilians were shot, 14 died. Many of the victims were shot fleeing the soldiers, and others while trying to help the wounded.

Outrage spread to Great Britain. Scott infiltrated the ISC, reporting on them from May to October 1972. He was appointed the coordinator for the donations of books to send to detainees.

He concedes that the organisation was not violent, but may have been supportive of people who were. Harking back to the formation of Special Branch – founded in 1883 to spy on Irish nationalists in London – he said:

‘this was the function of Special Branch in its origins and therefore they had a responsibility’

ANTI-INTERNMENT LEAGUE

He moved on to infiltrate the Anti-Internment League (AIL), another organisation opposed to detention without trial in Northern Ireland, from September 1972 to November 1973. He was unable to grasp the civil liberties and human rights issues, saying of the group:

‘It was about supporting the rebellion in Ireland really’

Characteristically, he contradicted himself a few minutes later. Queried about his report [MPS-0728845] that detailed a pro-bombing speech at the October 1972 AIL conference, he said such views weren’t common in the group:

‘there were many people that were essentially liberals that really, that just didn’t believe in interning people and that kind of thing.’

His report said that the conference disappointed many who came, and two members of the International Marxist Group, Géry Lawless and Bob Purdie, had taken leadership roles in the AIL.

TROOPS OUT MOVEMENT

In a September 1972 report [UCPI0000007991], Scott mentions the Troops Out Movement (TOM). He admits TOM was not violent, and did not seek to overthrow parliamentary democracy, but nonetheless:

‘Troops, I suppose, are of interest to all of us, including Special Branch. As an organisation upholding the law, they would be interested in anything that was actually anti the troops.’

There was also some crossover between TOM and the International Marxist Group, who were already targeted by spycops.

Lawless was involved in the running of TOM, and was already spied on by SDS officer Richard Clark who – as ‘Rick Gibson’ – had set up a TOM branch in order to climb through the organisation to its top level before sabotaging it. (See also the statement of Mary below.)

‘IMG is a virulent Marxist group and they were endeavouring to infiltrate anywhere they could really cause problems. But in the case of Géry Lawless, he was Irish, of course, and he was – what can I say? – he was a problem wherever he went… he was just a nasty individual actually.’

VIOLENCE AGAINST TRUTH

Scott was told Lawless had accused him of being a police officer. He decided he had to do something about in order to make everyone believe that the allegations were false.

Amazingly, the same night he was told of the accusation, while driving he apparently chanced across Lawless, who was making a call in a phone box. Going to the phonebox, Scott opened the door and confronted him angrily. On being told to ‘feck off’ he punched Lawless hard enough to chip a bone in his hand and require medical attention.

Scott laughed as he remembered this incident, claiming that Lawless was trying to take off his belt to defend himself.

Why was a crime of violence against a member of the public acceptable?

‘It was acceptable to me and I was the one that made the decision. I was the one that was there, and the person that was the so-called victim was Géry Lawless’

It was nonetheless a crime of violence, surely?

‘I don’t think so, no.’

Throughout this section of the evidence, the Inquiry’s Chair, Sir John Mitting, was visible on-screen. He did not appear to be taking this spycops criminality very seriously.

WORKERS REVOLUTIONARY PARTY

Scott chose the Little Ilford branch of the Workers Revolutionary Party (WRP) as his next target. He described the WRP as Trotskyists who were trying to infiltrate trade unions and foment industrial unrest.

We were shown one report [UCPI 0000006961] from 1975 to illustrate their ideological position. It referred to a march from Hull to Liverpool which would pass through the Yorkshire coalfields, where National Union of Mineworkers’ leader Arthur Scargill would be denounced as a ‘Stalinist betrayer of the working class’.

‘Peter Collins‘ (HN303, 1973-77), also infiltrated the Workers Revolutionary Party, with an unusual outcome. Not knowing he was a spy, the members asked him, in turn, to infiltrate a breakaway group of the far-right National Front.

Scott recalls meeting with Collins at the SDS safe house. He says he was not aware of this extra deployment into the far-right, and in fact says the two men never even discussed their shared experience of infiltrating the WRP.

There are many reports on the WRP, including a June 1975 report [UCPI0000012752] of a meeting of around 500 people in Liverpool that discussed the case of the jailed striking building workers known as the Shrewsbury Two.

Despite being credited as the report’s originator, Scott says knows nothing of any of these campaigns events or the case, including that the trials were held in Shrewsbury.

In April 1975, Scott reported [UCPI0000007111] on the forthcoming Catholic marriage of two members of the Little Ilford WRP:

‘It’s important to know that when members change their name by marriage and who they’re married to, it’s important to know. You build up a picture of what’s going on.’

This lack of proportionality took many forms. A month later, Scott reported [UCPI0000007176] that:

‘The Workers Revolutionary Party is actively considering infiltrating Labour Party Young Socialists with a view to the eventual subversion of all branches of the LPYS… Similar infiltration of other groups is being considered but apparently the Young Communist League has been rejected on the grounds that it is virtually non existent.’

Quite where the WRP were going to find thousands of people across the country to take over every branch of the Labour Party’s youth wing does not appear to have been considered.

After attending a WRP training course at White Meadows in Derbyshire, his deployment ended.

In all his five years undercover in the Special Demonstration Squad, Scott can only remember witnessing one occasion of public disorder. It was a demonstration in Whitehall and a man in a bowler hat trying to hit people with an umbrella. Scott can’t remember why, nor what the issue was.

Full witness statement of ‘Mike Scott’

‘Mary’

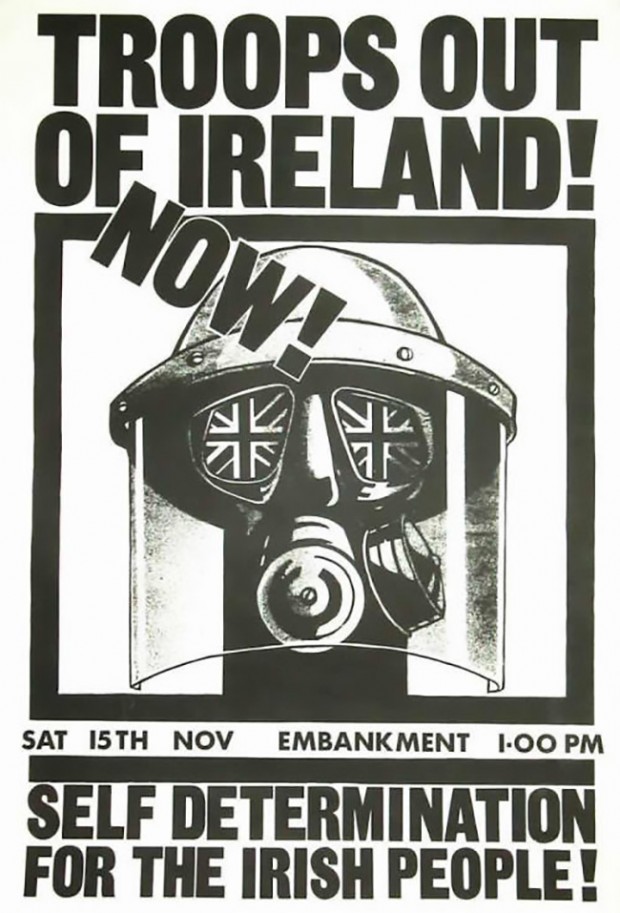

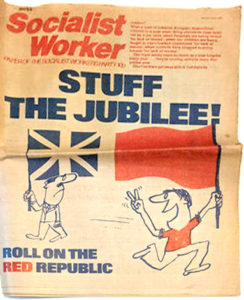

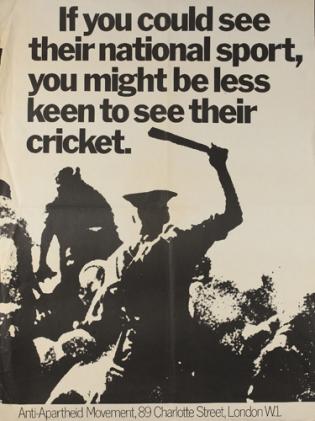

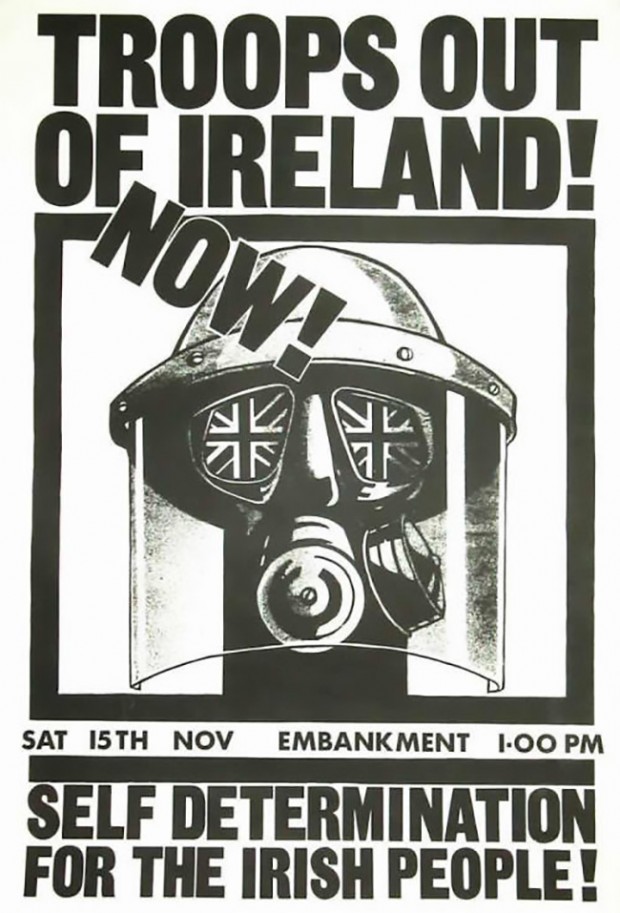

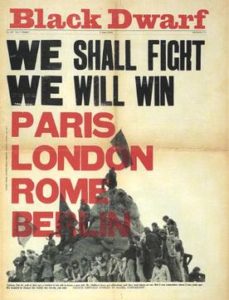

Troops Out of Ireland poster, 1975

‘Mary’ is one of the women who was deceived into a relationship by Special Demonstration Squad officer Richard Clark (‘Rick Gibson’ HN297, 1974-76).

Mary attended Goldsmith’s College in London from 1972 to1975, and joined the Socialist Society formed of students on the far left, including the International Marxist Group, International Socialists, and many independents.

The Socialist Society assisted students, and was involved in many campaigns beyond the campus, in workplaces, factories and communities in South London. It held weekly meetings with speakers on historical, economic and social issues. These often involved topical subjects, such as Vietnam and South Africa.

Mary recalls they also had speakers on issues of anti-racism, women’s liberation, academic freedom, civil liberties, free speech and human rights in general. One of their demands was for a daytime crèche for students who were parents. It was a successful campaign.

We were affiliated to and attended the local Trades Council, and we hoped to support local workers in their struggles for improved pay and conditions.

To support the national miners’ strike in the early 1970s, we adopted a mine in Wales. I visited the town and stayed with a local family to show our solidarity.

The Socialist Society also engaged in campaigns against the fascist National Front. Mary notes that it’s important to understand that during this time the fascists had united in one organisation. They were both racist and anti-democratic:

‘The State was standing by as the fascists organised. The police by their nature were institutionally racist, and as a result let the National Front organise at will’

Mary had come to London from South Africa, so the anti-apartheid movement’s struggle was especially close to her heart

During the period she was spied upon she also supported the International Marxist Group (IMG) and National Abortion Campaign.

‘I feel uncomfortable continuing to answer the questions about the IMG and my involvement in it. The questions appear loaded.

‘My activities were for social justice and in defence of human rights — which the last time I checked, are allowed in a democratic society.’

‘Seriously, I thought this public inquiry was meant to be investigating undercover political policing’

Her statements echoes what others have said last week. With the passage of time, many of the issues we were campaigning around have been shown to be completely justified.

We were on the right side of history.

In order to campaign effectively it required challenging the State, which is our legal right and responsibility as citizens:

‘At no point was I ever involved in conspiracies or discussions to involve myself in illegal or violent activities.

‘In fact, there were a number of occasions where I felt unprotected by the police when I should have been protected. Our meeting in East Ham Town Hall was smashed up, fascists coming into the building. The police who were outside stood back and let it happen.

I had forgotten that I had a ‘party name’ but have discovered from Rick Gibson’s notes that my alias was ‘Millwall.’ I sold Red Weekly every other week outside the Den, Millwall Football Club’s ground, and outside factories in south London. I have to say I was a braver woman than I thought I would ever be.’

EMOTIONAL ABUSE

We then get to the topic of the sexual relationship with Rick Gibson.

‘He was easy to befriend, he was a harmless sort of person and he was not predatory. He was very mild, very bland and also very boring.’

Last week at the Inquiry we heard that Rick Gibson built his career infiltrating activist groups, using relationships with four different women to win trust and build his cover story.

‘He was a frequent visitor to both myself and to my flatmate (who was also an activist). I assumed that our sexual encounters were a manifestation of a mutual attraction. They proved to be half-hearted and fizzled out.

‘Had I known he was a police officer there is absolutely no way I would have had any sexual contact with him at all. His use of sex was a way of consolidating his history, and to cement his reputation. He was using it to get closer to us as a group of activists.

‘I do find it appalling that in the reports for senior management ‘Rick Gibson’ has seemingly left out the sexual contact.

‘I find the whole strategy and practice of spycops having sexual relations with activists as immoral unprincipled and a criminal abuse of emotions. It is also an abuse of their own partners and families.

‘I am totally opposed to any acts of violence. That stems from my background of being aware of State violence in South Africa.

‘I would also add that the sexual contact that I and other women faced was a form of State violence.

‘Finally, I am angry with the Metropolitan Police. It took it upon itself to do this and had a cavalier attitude to privacy. Nor did the Metropolitan Police consider the rights of people to be involved in legal and genuine political activities.’

GIBSON’S ENTRANCE

Gibson wrote to the national office of the Troops Out Movement in December 1974. Quite likely, his membership application was a police response to the Birmingham pub bombing in November. He asked if there was a local branch in South East London.

‘His letter prompted myself and other activists, such as Richard Chessum, to meet with him and launch an entirely new branch. Without the undercover, it would not have existed.’

Mary first met Rick Gibson in December 1974 or early January 1975, when he approached her at a political stall at the University. Soon thereafter, the Socialist Society launched the Troops Out Movement in South East London, and had their first meeting.

As is now clear, befriending Mary and Richard Chessum was just a stepping stone to bigger things. Gibson became London organiser of the Troops Out Movement relatively quickly, and the convenor of the national officers next.

Mary probably saw Gibson for the last time in late 1975. As he became more and more involved in TOM nationally and moved up the ‘career’ ladder he became increasingly peripheral to her.

The Inquiry has asked her if she remembered other undercover officers active as well; ‘David Hughes’ (HN299/342, 1971-76), ‘Jim Pickford‘ (HN300, 1974-76), and ‘Gary Roberts‘ (HN353, 1974-78). Mary said she sadly she can’t be of help without further information, disclosure or contemporaneous photographs that the Inquiry refuses to supply.

GIBSON’S EXIT

Gibson was exposed by members of Big Flame who did not trust him, and in their investigation found both the birth and the death certificates for the real Rick Gibson, whose identity the spycops had stolen.

Mary was simply astounded when she found out he was a police officer. But certain aspects of Rick Gibson’s behaviour clearly fell into place.

‘He was always strangely unobtainable. He would not exchange contact details and he always had reasons why he could not be contacted. He said he worked for the water board and was often away.

‘He had no political back history, no other back history, he seemed to be extremely politically naive and also utterly new to the idea of activism.’

Looking back, it is clear that his sexual advances, and the use of sex was a way of ingratiating his way into the group as a whole.

‘I am disgusted that the police felt it appropriate to spy on people campaigning for better conditions for working class people, for democracy, civil liberties and human rights.

‘I am not traumatised, just feel embarrassed and foolish being used and conned. It really angers me as the police had no right to do this.

‘The only solace I can take is that that everybody else was fooled by ‘Rick Gibson’ as well until Big Flame found out who he really was.’

Finally, Mary wants to know what personal information is held on her by the police, Special Branch and MI5, and what was passed on when she moved to Cardiff. This includes her correspondence, whether her phone was tapped and what records there are of her conversations with her friends.

Mary believes that the intelligence reports that have been disclosed only form a small part of the whole picture, and hopes the Inquiry will disclose more.

‘The reports disclosed to me must have been seen by senior civil servants and Ministers.

‘This type of political policing is completely unwarranted. I would like to know who authorised this activity by the police, and how it was justified.

‘In a democratic society there is a duty to campaign and protest when and where necessary, the actions of the police and the undercover officers bring democracy into disrepute.’

Full Witness Statement of Mary

You can read more about this case at:

‘Rick Gibson’ – spycops sexually targeted women from the start, 28 November 2017

‘Mary’ proves: sexual targeting was always part of spycops, 30 January 2017

<<Previous UCPI Daily Report (30 Apr 2021)<<

>>Next UCPI Daily Report (5 May 2021)>>

Film: Solidarity (UK, 2019, 76mins), followed by panel discussion including director Lucy Parker, producer Kate Parker, and local groups.

Film: Solidarity (UK, 2019, 76mins), followed by panel discussion including director Lucy Parker, producer Kate Parker, and local groups.

The eighth day of the 2022

The eighth day of the 2022

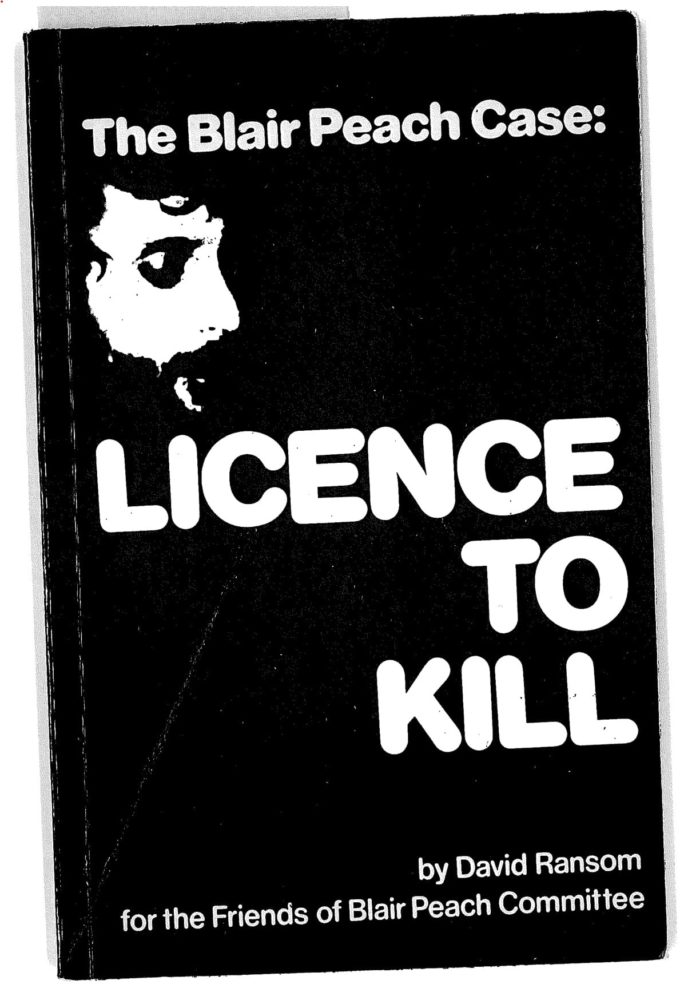

One of Peach’s friends and teaching colleagues, David Ransom, wrote a booklet called License to Kill about the killing of Peach and the Special Patrol Group. The chapter on the Special Patrol Group (SPG) is being published by the Inquiry along with the Cass report [

One of Peach’s friends and teaching colleagues, David Ransom, wrote a booklet called License to Kill about the killing of Peach and the Special Patrol Group. The chapter on the Special Patrol Group (SPG) is being published by the Inquiry along with the Cass report [

‘

‘

Barr asked Ali to account for his use of the word ‘militancy’. He explained that other groups at the time were demanding peace in Vietnam, but the VSC didn’t want ‘the peace of the graveyard’, they supported the Vietnamese people in their struggle against the American occupation.

Barr asked Ali to account for his use of the word ‘militancy’. He explained that other groups at the time were demanding peace in Vietnam, but the VSC didn’t want ‘the peace of the graveyard’, they supported the Vietnamese people in their struggle against the American occupation.

Resources, analysis and archives about the Undercover Policing Inquiry (UCPI).

Resources, analysis and archives about the Undercover Policing Inquiry (UCPI).