UCPI Daily Report, 13 Nov 2020

Tranche 1, Phase 1, Day 10

13 November 2020

Evidence from:

Officer HN330 aka ‘Don de Freitas’ (summary of evidence)

Officer HN321 aka ‘William Paul “Bill” Lewis’ (summary of evidence)

Officer HN322 (real name withheld) (summary of evidence)

Officer HN328 Joan Hillier

Officer HN326 ‘Doug Edwards’

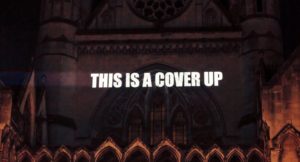

The Undercover Policing Inquiry had a full day of police witnesses, and it was a startling day of discovery.

This phase is only covering 1968-72, and today we learned that many of the spycops activities we’d been led to believe came later on were actually there from the start.

An officer having a sexual relationship with someone they spied on in 1968. An officer spying on a political group in Scotland in 1969. Officers pretending to be a couple to seem credible to the groups they infiltrated in 1968. An officer attending the wedding of someone he spied on around 1970. Officers going beyond the UK in their undercover persona before 1972. It seems that what the spycops units ever did, they always did.

If this is what we’re learning from what we’re told, just imagine what is being concealed by the anonymity orders that the Inquiry has granted to most spycops.

SUMMARY DISMISSAL

As with yesterday, one of the most significant exchange didn’t involve a witness, but the Chair’s irate interruptions of the victim’s barrister in order to prevent him from asking questions.

The day started with two short summaries of ‘Don de Freitas’, (referred to by the Inquiry as HN330), ‘William Paul “Bill” Lewis’ (HN321), and officer HN322, whose cover name is unknown.

Doing summaries of the careers of officers who are dead is one thing, but to have a lawyer simply read summaries of statements from living spycops without any apparent opportunity to challenge the evidence or question them is quite another.

Yet again, the Inquiry acts as if the police – whose decades of deceit and abuse are the subject – can be taken at their word, and those of us who were targeted can have no insight that hasn’t already occurred to the Chair, Sir John Mitting, and he can dismiss our objections out of hand.

‘Don de Freitas’

SDS officer HN330

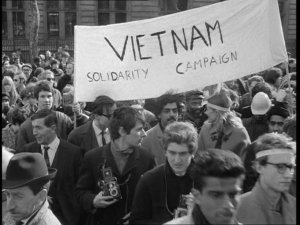

‘Don de Freitas’ served briefly in SDS for a month over September / October 1968, infiltrating the Havering branch of the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign (VSC).

As a Special Branch officer he used various cover names and occupation at different times, but his SDS deployment differed in that he used a fixed false identity.

Prior to his time with SDS, he had reported on Tariq Ali, and also Notting Hill VSC – particularly the Powis Square incident where members of the group were arrested.

Conrad Dixon, founder of the SDS

He knew the SDS founder Conrad Dixon socially and was invited to join the unit following a chance meeting in a corridor. He described the SDS as informal in nature.

Other than standard Special Branch training, he received no training or guidance. Operating out of Scotland Yard, he did not change his appearance other than to dress casually.

He initially went to a meeting of Havering International Socialists on 26 September 1968, which had been advertised in a leaflet distributed in Romford Market. He ingratiated himself with speakers and attendees which led to him being invited to join the private committee meetings.

COUPLED

Conrad Dixon suggested he and officer HN334, ‘Margaret White‘, attend the meetings together as a couple to make them less suspicious.

The remit was to find out as much as possible of the group’s plans for the big anti-Vietnam War demonstration of 27 October 1968. He stopped undercover work shortly after this demonstration, on 29 October. While with the group, he reported on their preparations including leaflet distribution and fly-posting, which he took part in.

His evidence gave a picture of a peaceful group, whose aims were not subversive and most members ‘unwilling to support civil disobedience or terrorism’.

ON THE MARCH

At the October demonstration, he marched with the group, chanting pro-Vietnam slogans. His final report is to note the general opinion of Havering VSC that the protest was a ‘complete and utter disaster’.

Among his reports was information on a Labour Party official, who was a member of Havering VSC. The officer notes this was included because MI5 were interested in whether extremists were penetrating what he describes as ‘legitimate left-wing political organisations’.

At one point, he was tasked to investigate information that an individual was seeking ingredients to make a smoke bomb. Another report in his name notes the plans of anarchists from University College Swansea for the October demonstration, but it is unclear how he came by this information.

Three documents, dated after his SDS time, show he was involved in the monitoring of the Anti-Apartheid Movement from July 1960 to June 1970. These were copied to MI5.

‘William Paul “Bill” Lewis’

HN321

‘Bill Lewis‘ now lives abroad and has provided a witness statement. He was deployed from 18 September 1968 to 30 September 1969. Soon after leaving the SDS he resigned from the police as he had ‘tired of the work’.

The majority of his reports focus on the International Marxist Group (IMG).

Prior to the SDS, he was with Special Branch’s B Squad where he would attend public meetings in casual clothes, noting attendees and their activities; he did not have a false identity for this. He was recruited to the SDS because a Special Branch manager had been impressed by the detail in his reports, and he was encouraged to attend a meeting regarding the formation of the squad.

INVITED TO SPY

He recalled going to a meeting of around 30 people in which Conrad Dixon said their work was going to be secret. HN321 accepted the invitation to join. There was no training or guidance; the objective was to gather intelligence on the 27 October demonstration against the Vietnam War.

His cover job was as an instrument and control technician, which he knew enough to talk about if necessary. He used two cover flats – one in Earl’s Court and another in Acton.

He would attend the SDS safe house several times a week, as advised by Dixon, to keep officers engaged during their downtime. The undercovers learned on the job and by sharing experience – for example how to avoid blowing their cover.

Not assigned to a particular group, he initially attended a demonstration and then a meeting, which he discovered was an IMG one. Dixon instructed him to attend further IMG meetings as they were a group of interest to the SDS.

Lewis’ first report covers a public meeting attended by Ernie Tate and the US socialist presidential candidate Fred Halstead. However, after that the IMG reports all cover private events. He also reported on Lambeth and other VSC branches.

On 26 October 1968, he telegrammed Special Branch to alert them to comments made at a South West VSC Ad Hoc Committee meeting in Brixton, that police coaches on Vauxhall Bridge would be sabotaged during the demonstration the following day. His witness statement however notes that he did not think the IMG would carry this out as they were ‘actually quite passive and intellectual’. He did not express this view to his managers, reporting only the facts of what took place at the meetings.

80 PEOPLE FILED

At one point, he was able to record the details of approximately 80 members of the IMG, which were passed on to MI5.

The subject of other reports related to discussions and planned demonstrations around Northern Ireland, the Middle East, the International Congress of the Fourth International, Scottish nationalism and women’s rights. There was also a debrief after the 27 October demonstration.

His last reports on the IMG were regarding the IMG’s 1969 education camp in Dunbartonshire, which he attended, giving a lift to three IMG members in his cover vehicle.

[This shows that SDS were travelling to Scotland from within the first year of the unit, much earlier than had been previously admitted.]

He states that his only criminal activity while undercover had been obstruction of the highway and perhaps fly-posting. Generally he recalls being advised not to resist arrest if it happened, and that it could be ‘sorted out’ further down the line with charges probably being dropped.

SDS officer HN322

Real name withheld

This individual served in SDS for a short time in its early months and was not deployed undercover. Their real name is being withheld by the Inquiry.

He was approached by Conrad Dixon who personally invited him to join the squad. He was not given much information initially. He had a young family at the time and, once he realised it would mean a lot of time away from them, he asked to be taken off the squad. He went on to have a senior rank in the Metropolitan Police.

In his experience, his time in SDS was much the same as time doing generic Special Branch work – both involved going to meetings and gathering intelligence.

He may have been directed to look at South East London VSC. He recalls being told to attend and report on a few different meetings. Reports show these were Earl’s Court VSC and the South East London Ad Hoc Committee of the VSC.

He wrote reports on behalf of officer HN335, Mike Tyrell, which covered private meetings and planned activities of the British Vietnam Solidarity Front and the Revolutionary Socialist Students Federation.

He notes the lack of direction and supervision within the SDS as compared to the rest of Special Branch. He was advised to go to meetings, but given no direction or guidance about what to do when in attendance, and had a lot of free time.

Joan Hillier

SDS officer HN328

Only known before today as officer HN328, Joan Hillier gave evidence under her real name.

In her oral evidence, there was a lot she said she couldn’t remember, and some contradiction of established facts.

Hillier joined the Met in 1958, and moved into Special Branch in March 1968, coincidentally the day after the disorder at a Vietnam War protest outside the American Embassy in London, which spurred the formation of the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS).

Hillier said there was little in the way of mentoring compared to when she’d joined the uniformed police. She got the impression that the Home Secretary had ordered that there be no repeat of the anti-war demonstration’s uproar and, in July 1968, Special Branch formed the SDS in response.

She remembers no application process, rather officers were invited from various Special Branch squads.

There was no formal SDS decision making on which groups to infiltrate, they ended to be selected by casual discussion among SDS officers. They were given casual, informal briefings on the politics of people they were going to spy on, rather than any structured lectures. Tactics were planned in detail, rather than targets. She said she did not remember any discussions about the risk of becoming involved in criminality.

PUBLIC ORDER OR POLITICAL POLICING?

At the time, Hillier was under the clear impression that the SDS was concerned with public order issues only, centered on the forthcoming October 1968 protest against the Vietnam War, rather than any wider counter-subversion spying. This is at odds with the fact that most SDS files were copied to MI5, who were not involved in public order policing.

She was shown a paper authored by the SDS founder and boss, Chief Inspector Conrad Dixon, about ‘penetration of extremist groups’ [MPS-0724119, not yet published at the UCPI website]. This was something she said she had no memory of seeing before.

Invited to define extremists, she said it was people who use extreme means – violence, disorder – to get what they want, seemingly without awareness that the threat and use of violence is the basis of the power of uniformed police.

The SDS was just another Special Branch squad, Hillier said, but with the added advantage of being members of targeted groups and so able to go to non-public meetings. And yet, many of Hillier’s reports are of public meetings, both before and after she joined the SDS.

WOMEN UNDERCOVER

Hillier’s written statements said that there were no female undercover officers in the SDS at the start, yet we’ve seen that there was not only herself and Helen Crampton, but officer HN334 whose statement says she had a cover job and address, which is even more involved than Hillier’s activity.

Spycops Helen Crampton (left) & Joan Hillier (right, redacted)

Her statements also described how only male spycops went to private meetings, yet reports show Helen Crampton and female officer HN334 did it.

Hillier accepted the evidence as true and blamed fading memories of things that happened over 50 years ago.

Conrad Dixon wrote a document stating that it was important that targets were unaware of spycops, so if there was the desire to get evidence and arrest someone in an infiltrated group, it is better to send female officers in as he believed they were less likely to be suspected. He followed this with a list of female officers including Hillier.

She said she had no memory of ever doing this, nor of Helen Crampton, with whom she worked as a pair, doing it either.

It was pointed out that in 1969, Crampton gave evidence in a prosecution arising from a meeting she’d attended with Hillier (more about this later). Hillier said she has no memory of this at all.

UNGUIDED

The lack of training and guidance was a major theme. Hillier doesn’t remember any instruction on what to include and exclude in reports. Your reports would contain whatever you thought reports should contain, she explained.

She did confirm that personal details (dates of birth, home addresses, etc) would be routinely added to Special Branch files ‘in case it was needed in the future’.

Hillier said that the SDS was able to obtain information that normal Special Branch officers couldn’t get. She confirmed that superior officers wanted to know in advance who would be at demonstrations, and so there was a desire for the supply of details on anyone involved:

‘Information is never wasted, really’

Reporting everything ‘in case it was needed in future’ because ‘information is never wasted, really’ is properly Orwellian. Watch anyone long enough and you’ll find something.

NO NEED FOR TRAINING

Despite her earlier description of only joining Special Branch shortly before the SDS was formed, Hillier blithely asserted that SDS officers didn’t really need training as they were all experienced special Branch officers:

‘Instinct would tell you what you shouldn’t do and what you should do’

Officers would instinctively know not to get involved in people’s personal lives, form intimate relationships, commit crime of appear in court under a fake identity, she said.

And yet, not only were these things standard practice in the SDS shortly after, we know that her contemporaries were dating people they spied on.

Specifically asked about officer Mike Ferguson, who infiltrate the anti-apartheid movement, Hillier said she only knew he was in that political area. She didn’t know any details, nor what managers knew of his activity.

SECRET PUBLICITY OFFICER

A document was shown a page from the Conrad paper mentioned above, describing the structure of the SDS. It said there was a Chief Inspector at the top, with three Detective Inspectors below them, one of which is tasked with ‘press and liaison’, which seems most peculiar for a secret unit.

Hillier had no idea what it meant, and said she’d never seen the document and doesn’t recognise the command structure it describes.

The same document has a section on ‘scope of activities’ which warned against becoming an agent provocateur:

‘The incompetence of the British left is notorious, and officers must take care not to get into a position where they achieve prominence in an organisation through natural ability. A firm line must be drawn between activity as a follower and a leader, and members of the squad should be told in no uncertain terms that they must not take office in a group, chair meetings, draft leaflets, speak in public or initiate activity.’

Hillier said she had never been warned of this, but she wasn’t undercover after October 1968 anyway, as she moved into the unit’s administrative staff.

AUTHOR OR SCRIBE

Asked about the content of a number of reports she made on meetings elsewhere, Hillier said that although she was the credited reporter, she was in fact merely the typist for the officers who’d done the spying. This certainly makes a change from the traditional amnesiac answers from police.

Hillier explained that spycops would hand her a report in pencil with a list of names, and she would look up the people’s file numbers, type it up, sign it on their behalf and pass it to Chief Inspector Dixon.

Signing for others wasn’t standard Special Branch practice, but was easier for the SDS as being split across two sites and not seeing one another regularly could lead to delays.

In her later administrative role, she described herself as the go-between for information between the SDS’ secret base and Scotland Yard, where no undercover officer could afford to be spotted.

Asked what the SDS was like, she replied:

‘when I joined, it was a very nice unit. It was very happy. Everybody got on well together. They were all going for a common cause. And it was a very happy unit. That’s the only way I can describe it really.’

ENTER MENON

When the Inquiry Counsel finished their questioning of Hillier, Rajiv Menon QC, representing some of the people targeted by spycops, applied to ask questions.

As with yesterday’s hearing, the most significant and instructive part of the day came not from a witness, but from the way the Chair treated the voice of those who were spied on. We’re describing this section in some detail to give a strong flavour of what we’re facing.

Menon said he had a number of points that he wanted to ask about:

- Hillier giving evidence in her real name;

- An issue relating to the ‘Penetration of Extremist Groups’ paper authored by SDS boss Conrad Dixon;

- Hillier & Crampton’s involvement with the Notting Hill branch of the VSC;

- Spycops having intimate relationships (the most pertinent one in the list, according to Menon);

- An issue about about Highgate & Holloway branch of the VSC;

- Inter-relations of the SDS with Special Branch and MI5.

Mitting said that disputes of fact can get questioned, but Menon would not be allowed to put ‘general questions’ of the kind he was suggesting.

Menon replied that all his questions were relevant to matters squarely within the Inquiry’s terms of reference, and will assist the Inquiry in its fundamental aim to get to the truth of undercover policing. He wanted to ask open questions to establish the ground from which he foresaw questions of specific fact emerging.

Menon pointed out that the hearing was ahead of schedule, so there was no pressure of time. He asked for a little latitude in favour of a barrister with 26 years experience, and the precise relevance of his questions would soon become visible. He added that his questions that were submitted to Counsel for the Inquiry in advance hadn’t all been asked, and he would only take ten or fifteen minutes.

NOTTING HILL VSC

Mitting homed in on the dispute of fact about Crampton in Notting Hill VSC. Menon wanted to be circumspect and ask open ended questions to see if it would settle a query as he has information from another source.

Mitting vaporised any chance of that approach by asking what the specific issue was. Menon said it was whether Crampton had a relationship with a leading Notting Hill VSC member.

Mitting vaporised any chance of that approach by asking what the specific issue was. Menon said it was whether Crampton had a relationship with a leading Notting Hill VSC member.

Mitting asked which member, and Menon replied that it was a George Cochrane, who is named in the reports as Chairman of the branch. This is an important issue as, if true, it shows spycops were deceiving people they spied on into relationships from the very start, contradicting what has been claimed by the officers of that era.

The Inquiry Chair followed up, asking if Cochrane was still alive (and would therefore have privacy issues). Menon did not know, but as Cochrane’s name isn’t redacted in the numerous documents the Inquiry is releasing, it indicates that the latter believes he’s deceased.

Mitting, though continuing to think Menon was impudent for wanting to ask questions at all, relented on this point. However, he imposed very tight parameters, saying ‘this is exceptional and I do not propose to invite you to ask questions on any other topic’.

QUESTIONING THE WITNESS

Menon then got the chance to question Hillier.

He refreshed what had already been said; that Hillier was with Crampton at all the Notting Hill VSC meetings she went to except one. He asked if she knew this particular branch had been disowned by national council of the VSC because of its politics (one of the three that VSC organiser Ernest Tate described yesterday as expelled Maoists).

Rajiv Menon QC

Hillier said she only went to about four meetings and wasn’t on first name terms with anyone. Menon said that, as she marched with the branch at the October 1968 demonstration, she must surely have exchanged names, which she conceded, adding that it would have been a cover name.

Menon asked if, when Hillier had said she didn’t know of any spycops having relationships with people they spied on, if it included going on dates. Hillier said she couldn’t say absolutely that it wouldn’t have happened, but she didn’t know of any instances.

Menon then asked his central question – did Helen Crampton have an intimate relationship with a Notting Hill VSC member? Hillier said she didn’t know for sure, but very much doubted it.

Menon led Hillier through some of the vintage SDS reports. A report of a Notting Hill VSC meeting on 2 October 1968 [MPS-0739188] shows George Cochrane was chairman, and Hillier was there with Crampton, as well as officers HN68 and HN331. Hillier signed the report. She replied that she didn’t remember Cochrane’s name at all.

ABSENCE OF EVIDENCE

Helen Crampton had given evidence in the trial of a man arrested after handing out a leaflet at the Notting Hill VSC meeting on 9 October 1968. Documents [MPS-0739187] show Hillier was at the meeting, along with Crampton, HN68 and HN331. Crampton’s report written the day after the meeting included mention of the leaflet.

Menon pulled up a file which showed the individual being convicted in 1969, on Crampton’s evidence, and given a two year sentence for incitement to riot. This was the only conviction the SDS directly secured in its early phase.

Menon pressed Hillier one whether she really couldn’t remember Crampton being involved, or whether Crampton getting the leaflet and showing it as something worth reporting for further action. Menon asked if Hillier had herself been a witness at the trial to corroborate Crampton’s account, but again she claimed she was drawing a total blank.

Despite her good memories of other events, Hillier had nothing at all to offer on the topic, and Menon could ask no further questions.

Oliver Sanders, one of the police barristers, then asked Hillier about her role in Highgate & Holloway. She’s already said she had no involvement with the branch, and yet there’s a report [MPS-0722098] on the branch that she signed. It has a list of names and addresses, and matches them with their Special Branch file numbers, or else says ‘no trace SB records’.

Hillier said, once more, that she didn’t author the report but merely typed it.

‘Doug Edwards’

SDS officer HN326

The afternoon was devoted to evidence from former spycop HN326, who used the cover name ‘Doug’ or ‘Douglas Edwards‘. (Despite it not being his real name, we’ll call him Edwards in this report for ease of understanding.)

Edwards was undercover in the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) from late 1968 to May 1971. He infiltrated various groups including anarchist groups, as well as the Independent Labour Party, Tri-Continental and Dambusters Mobilising Committee. He provided a witness statement to the Inquiry in 2018, and a further one relating to photographs in 2019.

UNSPECIFIED REMIT

Edwards said he was not given any training about the groups that Special Branch was interested in, or about the meaning of the word ‘subversion’. He was only in Special Branch for a few months, before his Detective Inspector (Saunders) invited him to join the new Squad. It was so secretive that he had no idea what he was being asked to join.

While he was part of the SDS, he understood that his job was to look at the different ‘left-wing groups that were fomenting trouble on the streets’. Inquiry Counsel Warner said ‘that sounds more like public order policing’.

Warner asked if he was collecting information to work out if the groups were ‘subversive’ or not. Edwards said that you needed to identify individuals and try and understand what their political beliefs were. He said there were all sorts of rivalries in political groups (Trotskyists and anarchists were ‘bent on causing violence’, apparently).

He was on probation within Special Branch for that first year, and recalled that ‘you had to do what you were told in those days’. The existence of the SDS was kept very secret.

Edwards said that SDS officers were told not to break the law, probably by DI Saunders and Chief Inspector Dixon. ‘You couldn’t go into a squat for instance’.

FIRST TARGETS

There wasn’t much else in the way of training, how to begin approaching their targets, nor exactly which groups to target, or other ‘fieldcraft’. ‘You had to play it by ear,’ he explained.

Edwards confirmed that he knew SDS officer Roy Creamer, ‘an intellectual and knowledgeable man about left-wing affairs’. He doesn’t recall a specific political briefing.

If the SDS was there to infiltrate groups intending to ‘undermine parliamentary democracy’, one wonders why the Independent Labour Party (ILP), who stood candidates for election, fit the brief. Edwards said he remembers being told to join the ILP, as this would give him a ‘handle to swing’:

‘The man in charge [HN325], he wanted me to look at an anarchist group; and I was told that the way to do this was to go to Piccadilly Circus and sit about there and I would be recruited; and I’d be able to be joining the anarchists. But of course it was a load of rubbish. You know, when I’d done that for a few nights, I thought, “Well, what am I wasting my time for?”‘

His statement describes visiting the place ‘somewhere in the East End’ where long-running anarchist newspaper Freedom was published. The Inquiry was shown a report that refers to a leaflet being printed by Freedom, about the ‘East London libertarians’ who wanted to occupy council houses for homeless families:

‘You couldn’t go into a squat, for instance. You couldn’t get involved with that.’

He agreed that whistle-blower SDS officer Peter Francis’ description of the early undercovers as ‘shallow paddlers’, who didn’t fully immerse themselves with their targets their successors did, is ‘an apt description’.

It’s a relative term, though. As was standard practice, Edwards integrated himself into the personal lives and social communities of the people he was spying on.

Asked about his attendance at the wedding of two activists, he explained, ‘I couldn’t not do it, that was the thing’.

He said he joined in the celebration at the pub afterwards, but didn’t go to the registry office. This meant that he avoided appearing in any of the photos. He even took a gift along for the happy couple (this was a ‘fancy tin opener’, according to an earlier statement!)

He knew in advance that he’d been invited to the wedding, but does not remember what his managers thought about this.

He recalled the difficulty of doing the job, of being matey with his targets while being ‘on edge’ all the time:

‘it wasn’t always easy to maintain your cover. But I did my best and I was successful with it.’

And what exactly was that success in?

WEST HAM ANARCHISTS aka TEENAGE GRAFFITI WRITERS

Edwards was sent to spy on West Ham anarchists, the oldest of whom was 21.

He reported on a meeting of eight of them, intending to produce leaflets for a forthcoming by-election with the slogan ‘don’t vote, all parties lie’. He reported the personal details of at least one member to be put on file.

He was asked about the rowdy day at the South African Embassy that he described in a statment was with the West Ham Anarchists:

‘That’s a good question. Do you know, I can’t remember that. I was on a demonstration outside in Trafalgar Square at the South African Embassy, and it got a bit tasty. They started smashing windows and it was violent, and there we are. The mounted police came in then, to try and stop things… I know they were anarchist groups because they were all chanting this “Anarchista!” was the order of the day.’

He said the group definitely committed some minor criminal damage and graffiti – ‘just making a nuisance of themselves locally’ – and this was covered in the local press.

ILP – ANTI-DEMOCRATIC SPYING

Logo of the Independent Labour Party

Edwards didn’t just use the ILP as a gateway into politics, he attended meetings and demonstrations with them, describing them as ‘quite left-wing, pleasant, sociable, wrapped up in a world of intellectual Marxism’.

Edwards was asked how a demonstration might ‘undermine parliamentary democracy’, and struggled to answer. He talked of the fear the police had of the ‘sheer volume’ of people involved in the demonstrations, and their revolutionary ideals. He remains confused about whether these revolutionaries were going for ‘total anarchy’ or a ‘socialist society’ though!

He was in the Tower Hamlets branch of the ILP, and reported them talking about organising an anti-fascist rally and a local rent struggle. There are some reports about the preparations for a debate between the National Front and the ILP. The meetings were very small, literally four or five people.

The closest they appeared to come to political violence was a conflagration in a pub between his ILP comrades and some other left-wing faction (he thinks it might have been the International Socialists, but wasn’t clear).

He chortled dismissively about the size of many of the left-wing groups, saying:

‘They got an exaggerated idea of their own importance. They sort of had daft ideas. And of course, it resulted in this punch up in the pub.’

Edwards seemed unaware that the more feeble and insignificant the group targeted, the more unjustifiable the infiltration.

His fellow undercover officers Phil Saunders and Riby Wilson watched the scrapping from a car on the other side of the street. They later told him they’d have come to his aid if he needed it, but he’s not sure they really would have done.

The Inquiry was shown a larger report containing more about the workings of the ILP, with information from ‘very reliable sources’ (the plural was noted). Edwards said that his intelligence would have been included in this report:

‘It’s a big justification really of them sending me to the ILP.’

Edwards denied influencing the ‘direction of travel’ of the Tower Hamlets ILP branch, saying he just kept quiet and made mental notes of what was going on. This isn’t easy to reconcile with the fact that he became branch treasurer.

Edwards explained that this was a small group, a ‘tin pot organisation’. He remembers setting up a Barclays bank account, and the branch didn’t have much money. Funds were spent on banners, or sent to ‘the Chilean earthquake disaster fund or something like that’.

He said he didn’t remember speaking to his managers about accepting the position of treasurer, or any reaction from them to this development:

‘I can’t truthfully say one way or the other. You know, I’m not going to make answers up.’

‘Of course not,’ the Inquiry counsel said smoothly.

IRISH CIVIL RIGHTS SOLIDARITY CAMPAIGN

The Inquiry was shown a report [MPS-0732317] about the Irish Civil Rights Solidarity Campaign’s Islington branch, made by Edwards and counter-signed by CI Saunders.

Edwards said that he never went to the group’s meetings, but he knows another spycop did, and he was ‘on observation’ duty for him at least one time.

He said he only went to one demo outside the Ulster Office in Berkeley Street, but apart from that, he didn’t cover any Irish groups – this was done by someone else.

In his witness statement, he said he’s seen two SDS reports ICRSC meetings, from September and October 1970, and he is their credited author. His statement says that he did not in fact write them. In the same statement he described the ICRSC as ‘a front for the IRA’.

He admitted today, that he would have reported finding out that someone was a member or a supporter of such a group.

TRI-CONTINENTAL

The next document [UCPI0000008209] was a November 1969 report about the ‘Action Committee Against NATO’. There had been a meeting of the committee on 5 November – only three people were present.

According to the report, Tri-continental provided money for the deposit, so they could book meeting space at Conway Hall.

Edwards thought that Special Branch files were automatically destroyed after 30 years and seems perturbed that these have been ‘dragged out from somewhere’. He suggested from the ‘hairy cupboard’ (he likes his ‘jokes’).

He suggested that his managers would have been interested in this anti-NATO group, because they were worried about these ‘demonstration people’ targeting something that was ‘vital for the security of the country’.

He said that he can’t remember anything about Tri-continental. Let alone whether they ever did anything unlawful or got involved in public disorder.

DAMBUSTERS MOBILISING COMMITTEE

The Dambusters Mobilising Committee (DMC) was a coalition of groups opposing the proposed construction of the colossal Cahora Bassa dam project in Mozambique. The project was intended to supply electricity to apartheid South Africa.

Edwards was asked if he could remember the Dambusters group buying Barclay’s bank shares so they could attend the AGM. Did the Dambusters commit any serious crimes? Were they violent? Were they involved in any public disorder?

Edwards was even less forthcoming than he had been about Tri-Continental, saying ‘you’re asking me things I can’t answer. I can’t speak for the managers and what they thought’.

His witness statement from February 2019 was somewhat more expansive but no more specific:

‘DMC was concerned with a dam in Mozambique or South Africa and it had something to do with South African politics too. I do not remember what the group stood for or what they did. I do not remember how I infiltrated the group or why I infiltrated them. It may have been something to do with the group being on the fringes of all of the trouble with the movement against apartheid.’

The fact that the officer can’t even remember the politics of a group he was part of, suggests it made very little impression on him. This is not what we would expect to see from membership of a group committed to serious disorder, which is what the SDS claims it existed to spy on. The fact that he thinks it may be allied to undermining the struggle against apartheid compounds the sense of anti-democratic action emanating from his words.

SOCIALIST ALLIANCE AGAINST RACIALISM

An April 1970 report by Edwards on a new socialist anti-racist group, Socialist Alliance Against Racialism (SAAR), was shown to the Inquiry. Once again, Edwards said he didn’t remember them at all.

Mark Kennedy’s injuries after beating by police, 2006

He was asked if it being a ‘campaign against racialism’ would have made it of interest? Or because of the groups involved in founding it? And what his managers’ attitude towards the group was?

He did did not recall much.

There were some questions about the VSC, and a report about their planning meetings before a peaceful demo which took place in the autumn of 1970. He, personally, considered the VSC a front to cause trouble.

He confirmed that he himself was assaulted on a demonstration in Grosvenor Square, by uniformed police armed with truncheons. Asked why the police had gone for him, he said:

‘it’s just the fact you’ve got long hair and a beard and they wallop you, you know, you’re you’re one of them sort of thing. It’s 50 years ago, this was what they were doing. It’s a different attitude to things.’

His faith in the restraint of more modern uniformed officers is quaint. Any number of undercover officers have stories of the brutality of their uniformed colleagues.

At the 2006 Climate Camp at Drax coal-fired power station in North Yorkkshire, spycop Mark Kennedy was so badly beaten by a group of uniformed officers that he reportedly needed surgery on his lower back.

WORKING ABROAD

In complaining about the difficulties of his role, Edwards casually and seemingly unwittingly dropped a bombshell. It had long been thought that SDS officer didn’t go abroad until later on. Peter Francis believed his trip to Germany in the 1990s was the first.

Yet Edwards, who left the job in May 1971, said:

‘I went to Brussels with this other officer whose name I can’t even mention, I suppose, but, you know, the amateurish way that it was done then, it was a strain.’

Whatever the spycops ever did, it seems they always did.

END OF DEPLOYMENT

Edwards was undercover in the SDS for about two years. He finished because:

‘I’d had enough. I’d had enough of going round with a long beard and long hair and being scruffy. It’s quite a strain on the system doing the job, it really is… until you’ve done the job you don’t know what is involved’

Edwards mused about how it had got more difficult later on, for the spycops who came later and got more deeply embedded, for longer periods.

His deployment’s peculiar mix of pointless triviality and undermining of fundamental rights is captured in his 2019 witness statement in which he said:

‘I did not have any idea of how I was helping, one way or the other: nobody ever told me or gave me feedback and there was no other way of me knowing’

After his time with the SDS, Edwards returned to work in other areas of Special Branch. He took on a more clerical role in undermining democratic organisations, and began working on the ‘industrial desk’, which spied on trade unions and is thought to have illegally supplied details on union activists to private blacklisting companies. He said he didn’t know what was done with this kind of information – ‘obviously it would go to the security service in the first instance’.

Later in his career he worked in the ‘vetting office’. This was primarily security vetting of new recruits to the police, including members of Special Branch itself, done in conjunction with MI5. They sent the completed from off to MI5, who would respond if they considered somebody a security risk.

THE SECRET WASN’T SECRET

Edwards said he was sure the existence of the SDS wasn’t a secret among the top brass. He noted the way ‘all the management all ended up as top commanders and all the rest of it’, and he reminisced about the time that a senior officer brought a bottle of whisky along to the SDS to say thank you for their work.

In his witness statement, he said it was presented at the SDS safe house by the Commissioner or Assistant Commissioner. Whistle-blower officer Peter Francis said exactly the same thing happened to him after the anti-fascist demonstration in October 1993, when the bottle was presented by the Commissioner himself, Sir Paul Condon.

Edwards repeated and expanded on a line from his witness statement:

‘I was just a small cog in a great big machine and I did my little bit as best I could to help the police and the uniformed police and be a good branch officer. That’s what it’s all about, you know. Loyalty to the Branch’

He then veered into a bitter rant about those who’ve exposed decades of the unit’s counter-democratic action and violation of citizens by the thousand. With no trace of irony, he lamented the pain he feels because those he was close to have betrayed his trust.

‘And of course we’ve not seen now any loyalty from some of these people, and that I find very upsetting. You know, when you can’t trust people. I’ve not been to reunions and things like that, because you don’t know who you can trust any more. People are all talking to the press and everybody else, and can’t keep their traps shut. So I’m disappointed. I’m disappointed. You have a long career and that’s what happens.’

That concluded the second week of the Undercover Policing Inquiry’s evidence hearings. They will continue next week (Monday, Wednesday and Thursday are definite, other days undecided as yet), then there will be a break until around April.

COPS will be live-tweeting all the Inquiry hearings, and producing daily reports like this one for the blog. They will be indexed on our UCPI Public Inquiry page.