Spycops – Where It All Began

Police on horseback charge demonstrators against the Vietnam War, Grosvenor Square, 17 March 1968

1968 was a time of tumult around the world. Political dissent was brewing to a boil in Paris, Mexico City, Berlin and beyond. The civil rights movement, and latterly opposition to the Vietnam War, had brought a new wave of confrontation to the streets of America and the screens of the world.

In Britain, the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign (VSC) had been set up in 1966 and attracted a broad mix of people from the left of British politics. It was supported publicly and financially by venerable peace activist, the then-94 year old Bertrand Russell, who had left the Labour Party in protest at its stance on the Vietnam War. (Woodsmoke blog describes the background of its formation and events that followed.)

There had already been a demonstration outside the American Embassy in London’s Grosvenor Square in October 1967 that passed off without much incident. But the militant political mood, galvanised by outrage at the escalating horrors of the Vietnam War, meant the next one on 17 March 1968 would be much larger.

The war, already prolonged and brutal, was intensifying. Though the world wouldn’t know it until late the following year, two days before the march American troops had killed at least 347 people in the My Lai massacre.

SQUARING UP

It has been said that the Metropolitan police weren’t expecting trouble on the day, but that isn’t entirely true. Coaches travelling to the demonstration were stopped and thoroughly searched, and people were charged with possession of offensive weapons using a broad and creative definition of the term – in one case, it was a sachet of pepper.

As always, estimates of the size of the demo vary, but it’s thought around 80,000 people rallied in Trafalgar Square to be addressed by activists including actor Vanessa Redgrave. Afterwards, a crowd of around 15,000 marched to the American Embassy in Grosvenor Square. The plan agreed with police was that demonstrators would be kept on the roads around the square, and a small delegation led by Redgrave and Tariq Ali would go to the embassy itself to present a letter.

The access route was changed at the last minute. The crowds in Trafalgar Square weren’t told, and so there was confusion when entry to the square was bottlenecked by police. Feeling as if police were trying to block the way, then squeezing a gap in police lines only about eight metres wide, the marchers felt the tension markedly increase.

Though police were used to forming solid barriers to protect buildings, (eg buses would be parked across the entrance to Downing Street as demonstrations passed), for some reason they chose to defend the American embassy with police officers on foot, supported by others on horseback. This inevitably drew heckles and the volatile atmosphere headed towards ignition.

As the crowd funnelled out into the centre of the square, as they had at the previous demonstration, police saw them as deviating from the original plan to be in the three streets around the edge. Officers on horseback galloped in to disperse them, batons flailing, with no regard for the safety of those they were charging into.

EYEWITNESS ACCOUNTS

Counterculture legend Mick Farren described it:

‘They came at us like the charge of the Light Brigade, these mounted police sweeping across the square. They had these long clubs, kind of like sabres. We said “get under a tree so they can’t get a clean shot at you”.’

Many among the crowd responded by throwing whatever they could in return – stones, fence posts, clods of earth. Protestors broke the police lines, rocks and fireworks were hurled towards the American embassy. Somewhere in the chaotic scene was Mick Jagger, who shortly afterwards wrote Street Fighting Man, an uncompromising call for revolution.

A magistrate, Mr E Appleby, later described the scene to the Guardian:

‘One case will illustrate. An inoffensive student of exemplary character and integrity, standing some distance from the police, taking photographs, was set upon by four policemen shouting “Let’s get this one!” He was dragged into a van and told not to use his camera or he would not see it again.

‘Next day he was charged by his assailants with assault and summonly convicted. No opportunity had been given him to use a ‘phone or to contact his parents. And no time before or after his arrest had he done anything which could be remotely construed as an assault!’

One of the 25 legal observers from the National Council for Civil Liberties was watching another neutral figure, a journalist, but both were pulled into more involved roles:

‘When the superintendent reached the cameraman—with the clear aim of destroying camera and film (and film-maker too if necessary)—about a dozen other people, half police, half civilians, converged on the pair, the former concerned to aid the superintendent and the latter to rescue the camera and cameraman.

‘For my own part, I took only two steps forward when I was surrounded by five policemen, received a knee in the groin, was thrown to the ground and kicked by five or six boots. After a time I was hauled up and according to accounts of witnesses afterwards two attempts were made to arrest me but I was not in a state to respond and in the end was dropped.’

Mick Brown recalled:

‘The whole thing was disorganised. The police weren’t lined up and charging the way they would be now. There was just a general melee.

‘It was probably not intentional but this young girl of about 18 got trapped underneath a [police] horse and was in a state of panic. I’m not sure the rider was that aware of what was going on. All I did was pull her out. To do that I had to bend down more or less underneath the horse and so the policeman hit me over the head.

‘I left the square – I was a bit stunned. When I was outside the square I saw a friend of mine quite close to me. He leant over to a policeman who had his back to him and he tipped the policeman’s helmet off. He turned and ran. The policeman saw him so I stepped in front of him. I didn’t hit him, but I must have obstructed him. And he said, “Right, if I can’t get him I’ll get you.”

I didn’t realise the seriousness of it and he arrested me. He charged me with assault.’

The officer told the court Brown had grabbed him round the neck and punched him in the face several times. Brown was sentenced to two moths in Brixton prison and never went on another demonstration.

EXTRAJUDICIAL PUNISHMENT

It doesn’t matter whether an action or campaign has violent intent. It doesn’t matter whether it plans anything illegal. Some campaigns are deemed politically unacceptable and they are met with an array of police behaviours that amount to extrajudicial punishment. They are faced with police violence, arrest, protracted spells of detention, trumped-up charges and home raids. These are disproportionate but very difficult to challenge legally. Even if a victim is one of the sliver of a percent who bring a successful claim for wrongful arrest, they have still had to endure the treatment.

Political movements are broken by separating the deeply committed from the rest who can be discouraged from participation or bought off with minor compromises. Police punishments make everyone who hears about them choose between risking being subjected to them or staying away. It’s an effective way to curtail an increasingly popular movement and teach people not to challenge authority.

It’s the instinctive reaction of a state that fears the power of people who are calling for a world different from the one the government delivers.

START OF THE SPYCOPS

By the end of the day on 17 March 1968, 246 people had been arrested. It was political violence on British streets of a kind unknown since battles against fascists in the 1930s. It shocked the public and shot fear into the hearts of the political elite.

The government and police were terrified of the revolutionary fervour sweeping the world. A few weeks after the March demonstration, the French government was almost overthrown by ‘les évènements’ of May 1968. Could the UK be heading the same way?

Chief Inspector Conrad Dixon of the Metropolitan Police’s Special Branch said he could deal with the problem.

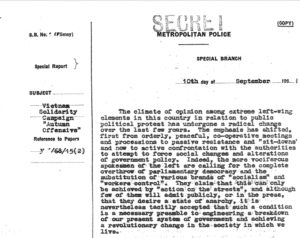

On 10 September 1968, Dixon prepared a report for his bosses.

‘The climate of opinion among extreme left-wing elements in this country in relation to public political protest has undergone a radical change over the last few years. The emphasis has shifted, first from orderly, peaceful, co-operative and processions to passive resistance and “sit-downs” and now to active confrontation with the authorities to attempt to force social changes and alterations of government policy.

‘Indeed, the more vociferous spokesmen of the left are calling for the complete overthrow of parliamentary democracy and the substitution of various brands of “socialism” and “workers control”. They claim this can only be achieved by “action on the streets”, and although few of them will admit publicly, or in the press, that they desire a state of anarchy, it is nevertheless tacitly accepted that such a condition is a necessary preamble to engineering a breakdown of our present system of government and achieving a revolutionary change in the society in which we live”.

(For more on this, see the Special Branch Files Project’s section on released documents about police reaction to anti-Vietnam War protests.)

Conrad Dixon’s Special Branch memo, 10 September 1968

Asked what he would need, Chief Inspector Dixon is said to have replied ‘twenty men, half a million pounds and a free hand’. That’s what he got. He set up the Special Operations Squad (SOS) which, in 1972, would change its name to the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS).

Around ten officers would be deployed at a time. They handed in all their police identity documents, changed their appearance and went to live among their targets, becoming one of the activists they were spying on.

Though we are told they were warned not to become agents provocateur, take office in organisations or have sexual contact with people they spied on, it’s clear that all these things were mainstream tactics in the unit from very early on.

THE NEXT MARCH

Vietnam Ad Hoc Committee leaflet, October 1968

On 27 October 1968 there was another march against the Vietnam War. This time, the police were ready and so were the press. The Observer declared that ‘to allege that the British police are violent is as dazzling a piece of hypocrisy as the big lies that Hitler once remarked deceive people more than small ones’.

Organisers, too, had taken steps to avoid a repeat of the violence in March. The Ad Hoc Committee – an umbrella co-ordinated by the VSC – issued leaflets calling for no militancy and no excuses for arrests.

The VSC said 100,000 attended the protest, while contemporary media accounts (presumably taking figures from the police’s notoriously implausible underestimates) said it was around 30,000.

Whichever, the bulk of the march stuck to the planned route, passing Downing Street where Tariq Ali handed in a petition of 75,000 signatures calling for an end to British support for the American side in the war, before heading on to Hyde Park.

A separate, more confrontational, group on the demo openly planned to go to Grosvenor Square, but VSC activists succeeded in ensuring that the bulk of the march did not join in.

Nevertheless, several thousand broke away for the now-familiar Grosvenor Square set piece. Though there was a four-hour stand off with some fireworks and argybargy, there was nothing on the scale of the March riot.

Despite the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign’s rejection of political violence at that moment, it was the major target of the first spycops. Of the five SOS/SDS officers known to have been deployed in that first year, four were in the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign.

The unit rapidly expanded its remit. Within a year it had infiltrated the Independent Labour Party, and spread out through peace, workers’ rights and anti-capitalist groups to anti-racist campaigns, Irish nationalist campaigns (which had been the sole remit of the Met’s Special Branch when it was formed in 1883), far right groups and later into environmental and animal rights campaigns.

ORDERS FROM ABOVE

This was not just paranoid police inventing a job for themselves. The SOS was to be secretly and directly funded by the Home Office. Who gave the instructions? How much oversight did the politicians have? What did the Home Office think they were paying for?

A short while after the spycops scandal broke in 2011, Stephen Taylor, a former Director at the Audit Commission, was commissioned to investigate the Home Office’s links with the SOS/SDS. He searched every archive and found nothing. Millions of pounds spent by the Home Office yet not one single page of evidence has been kept.

Taylor’s slender 2015 report unequivocally said:

‘it is inconceivable that there would have been no discussions within the Department or with Special Branch’.

Time and again he had found reference to a file, catalogue number QPE 66 1/8/5, understood to have covered Home Office dealings with the SDS. It has disappeared. It would have contained material classified Secret or Top Secret, which would have strict protocols around its removal or destruction, yet there is no clue as to what happened to it. They physically searched all storage facilities in the Home Office. It’s gone.

Taylor couldn’t make allegations but rather pointedly said ‘it is not possible to conclude whether this is human error or deliberate concealment’.

Taylor did not dig deep. He does not appear to have spoken to any of the twelve living ex-Home Secretaries when investigating. The Undercover Policing Inquiry has dragged on so long that two former Home Secretaries and a former Met Chief Commissioner have died since it was announced.

Fifty years on, we still have no answers as to why it all happened, what it was all for and who was really responsible.