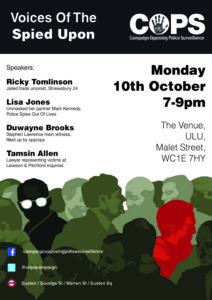

Video: Voices of the Spied Upon

New on our Youtube channel – video of the speakers at our ‘Voices of the Spied Upon’ meeting at the University of London, 10 October 2016.

Lisa Jones was an environmental and social justice activist. In 2010 she discovered that her partner of six years, Mark Stone, was actually Mark Kennedy of Britain’s political secret police unit, the National Public Order Intelligence Unit.

She gathered evidence, confronted and exposed him. This began a slew of revelations that dragged the murky world of the political secret police into the light.

Eschewing media exposure, Jones was one of eight women who took legal action against the police and, after a gruelling four years, received an unprecedented apology in November 2015.

In this, her first public speech, she talks about Kennedy, the court case, political policing, the forthcoming public inquiry and her hopes for the future.

‘Lisa Jones’ is a pseudonym. She has been granted an anonymity order by the courts to protect her identity, and this video has been made without breach of that.

Duwayne Brooks was the main witness to the murder of his friend Stephen Lawrence in 1993. This began a campaign of persecution by the Metropolitan Police.

Special Demonstration Squad whistleblower Peter Francis has described spending hours combing footage of demonstrations, trying to find anything to get Brooks charged. He was arrested numerous times and on two separate occasions he was brought to court on charges so trumped up that they were dismissed without him even speaking.

The Met have admitted that, years after Stephen Lawrence’s murder, police were bugging meetings with Brooks and his lawyer.

A veteran of the machinery of inquiries, a repeated victim of spycops, as the Pitchford Inquiry into undercover policing looms, Brooks’ experience and perspective is especially important and pertinent.

Tamsin Allen has represented many clients who were spied on by political secret police. She is a partner at Bindmans, a law firm who were monitored by the Special Demonstration Squad.

She has represented victims at the Leveson Inquiry into tabloid newspaper phone hacking and improper relationships between police and journalists. She is representing members of parliament who were monitored by spycops.

Her experience of public inquiries held under the Inquiries Act puts her in an invaluable position as we prepare for the Pitchford inquiry into undercover policing. Here, she talks about the issues with setting up the inquiry and what we can expect from it.

Ricky Tomlinson, before we knew him on TV as Jim Royle or Brookside’s Bobby Grant, was a construction worker and trade unionist.

In 1972 he took an active part in the first ever national building workers’ strike. Tomlinson was among 24 people subsequently arrested for picketing in Shrewsbury. Government papers now show collusion between police, security services and politicians to ensure these people were prosecuted. Six, including Tomlinson, were jailed.

He is one of several high-profile figures who, despite concrete evidence of being targeted by spycops, has been denied ‘core participant’ status at the Pitchford Inquiry into undercover policing.