UCPI – Weekly Report 11: 22-25 July 2024

This summary covers the fourth week (22-25 July 2024) of Tranche 2 hearings of the Undercover Policing Inquiry (UCPI), which continues to examine the activities of the Metropolitan Police’s secret political unit, the Special Demonstration Squad, from 1983-92.

This summary covers the fourth week (22-25 July 2024) of Tranche 2 hearings of the Undercover Policing Inquiry (UCPI), which continues to examine the activities of the Metropolitan Police’s secret political unit, the Special Demonstration Squad, from 1983-92.

The UCPI is an independent, judge-led inquiry into undercover policing in England and Wales. Its main focus is the activity of two units who deployed long-term undercover officers into a variety of political groups: the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS, 1968-2008) and the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU, 1999-2011). Spycops from these units lived as activists for years at a time, spying on more than 1,000 groups.

CONTENTS

Introduction

Observations

Monday 22nd July (Day 11)

Live: HN25 ‘Kevin Douglas’

1987-1991: Troops Out Movement / Haringey, and Broadwater Farm Defence Campaign

Tuesday 23rd July (Day 12):

The Case of HN95 Stefan Scutt ‘Stefan Wesolowski’

1985-1988: Socialist Workers Party / Hackney

Live: HN90 ‘Mark Kerry’

1988-1992: SWP / South London

Wednesday 24th July (Day 13)

Live: HN56 ‘Alan Nicholson’

1990-1991: British National Party, Loughton

Thursday 25th July (Day 14)

Live: Lindsey German, Socialist Workers Party

INTRODUCTION

This week’s hearings over-ran from the expected three days into four. In the first three we heard live evidence from three former SDS undercover officers:

- HN25 ‘Kevin Douglas’, deployed in Haringey against the Troops Out Movement and the Broadwater Farm Defence Campaign in the late 1980s and early 1990s

- HN90 ‘Mark Kerry’, who infiltrated various Socialist Workers Party branches in South London in the late 1980s and early 1990s

- HN56 ‘Alan Nicholson’ who was briefly deployed to infiltrate the British National Party (BNP) in Loughton 1990/91

We also had the unusual presentation of the case of HN95 Stefan Scutt ‘Stefan Wesolowski’, a former SDS officer. He was deployed into the SWP in Hackney 1985-88, but is not cooperating with the Inquiry. His troubled time in the SDS and subsequent mental health issues caused something of a crisis within the unit.

On the fourth and final day we heard powerful testimony from Lindsey German, for 30 years a key figure in the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) and currently the convener of the Stop the War Coalition.

German, who had been on the SWP’s central committee from 1979-2009, provided crucial insights into the party’s activities, its involvement in various social justice campaigns, and the impact of undercover policing on political groups.

She offered a refreshing counterpoint to the police narratives heard earlier in the week, challenging the inaccuracies and bias in the secret police reports, the offensive characterisations of activists, and highlighting the long-term consequences of surveillance on political organisations and civil liberties.

OBSERVATIONS

The case of Stefan Scutt was extraordinary, both for the significant ethical and operational breaches that occurred during his deployment and for the handling of his subsequent mental health crisis, details of which were kept secret from both the Home Office and the Security Service.

Another interesting departure from the norm in these hearings was the evidence of HN56 ‘Alan Nicholson’ who, unlike every officer to give evidence so far, was deployed (albeit briefly) against the far-right rather than against the left. It was bizarre that the local British National Party group he was ordered to infiltrate was virtually dormant.

Perhaps the most striking moment of his evidence was his revelation that for some of the time he was undercover he was terrified he might be ‘outed’ by a fellow police officer who may have had far-right sympathies.

The other two undercover officers (HN25 ‘Kevin Douglas’, and HN90 ‘Mark Kerry’) hammered home more familiar themes of minimal training and unclear guidelines.

Evidence continued to reveal the shocking breadth and depth of reporting of private and personal information with questionable relevance to policing concerns, with the striking admission from HN90 ‘Mark Kerry’ that one reason for recording such personal details was for the potential it created to ‘recruit informants’ (ie through blackmail).

Yet again questions were raised about the ideological and political (rather than policing) motivations behind a lot of the surveillance, particularly in relation to the Socialist Workers Party, and the events and campaigns it supported.

Throughout the week we saw a profound disconnect between perceived or alleged ‘public order threats’, and observed reality. In many cases, the groups under surveillance for alleged public order concerns were described as non-violent and posing little actual threat, raising yet more questions about the necessity and proportionality of the operations.

Indeed, once again it demonstrated the police’s unacceptable and anti-democratic efforts to snoop on and undermine people committed to promoting and defending the interests and rights of the public, and to challenge oppression and injustice in our society.

Monday 22nd July (Day 11)

Click here for video, transcripts and written evidence

Live: HN25 ‘Kevin Douglas’

HN25 ‘Kevin Douglas’ provided testimony about his infiltration of the Haringey Troops Out Movement and the Broadwater Farm Defence Campaign in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

He joined the Metropolitan Police in the early 1980s, initially working with C Squad investigating the extreme right wing before moving to B Squad, which focused on Irish nationalism. He then joined the SDS.

Recruitment and Training

His path to the SDS began with gossip and innuendo in the police canteen. Despite being in Special Branch, he claimed not to know exactly what the SDS was, though he was aware of intelligence coming from covert sources. He noted that officers would disappear and reappear after a couple of years, hinting at undercover activities.

The recruitment process for the SDS was informal, relying on word of mouth. HN25 ‘Kevin Douglas’ volunteered because he was ‘interested in politics and how society worked’. He spoke to HN85 Roger Pearce ‘Roger Thorley’ at a social gathering about putting his name forward and also discussed applying with HN350 Paul Croyden, with whom he had worked previously.

He didn’t feel the need for any special preparation for his SDS interview, stating that he ‘always kept a close eye on political issues’. The interview, conducted by three senior officers, focused on his motivations to join and what he thought would make a good undercover officer. Notably, the legal and ethical parameters of the role were not discussed during this process (nor it seems at any time afterwards).

HN25 ‘Kevin Douglas’ described joining the SDS as prestigious, calling it ‘the ultimate for a Special Branch officer’.

Training and Preparation

He described the SDS tradecraft manual as ‘formal’, which is quite hilarious considering its content. He (incorrectly) emphasised that it did not contain any guidance on sexual relationships, saying, ‘it was very safe advice’. He believed lying was sometimes necessary for the greater good:

‘As a policeman you are given tremendous powers. You are in many ways implementing the law which fundamentally requires honesty’

Asked about the dishonesty inherent to his undercover role, he said:

‘It comes back to the greater good, the necessity to sometimes lie in order to achieve issues’

Before his field deployment, HN25 ‘Kevin Douglas’ worked in the SDS back office, handling administrative reports. He stated that he never edited the content of reports and, when unsure about the value of information, would ‘err on the side of caution and report it’. This approach would later be reflected in his own extensive reporting during his deployment.

Cover Identity and Infiltration

Like many SDS officers, HN25 ‘Kevin Douglas’ stole the identity of a dead child. He followed the tradecraft manual in this process, despite feeling uncomfortable due to his own mother having lost a young child.

He shockingly defended the practice:

‘You would hope you would do justice to the youngster involved’

Stealing not only the child’s name but also parts of his life story, HN25 ‘Kevin Douglas’ travelled to Newcastle to familiarise himself with the area where the real Kevin Douglas had been born.

The ghoulish advice he says he was given was that the longer the child had survived, the better for using the identity as cover (as it would be harder for anyone to research and find a death certificate). Incredibly, he was not asked to hand back the stolen birth certificate at the end of the deployment, so he kept it.

HN25 ‘Kevin Douglas’ went to great lengths to change his appearance for his undercover role. He mentioned getting a perm, growing and dying his hair, and acquiring a new wardrobe.

During his deployment, he lodged with a family in Ponders End, eating meals and watching TV with them. He even attended a baby’s christening with them, explaining that it would be rude not to. Despite feeling uneasy about this arrangement (ie lying to them about who he really was), he had trouble finding somewhere else that suited him.

Infiltration Activities, Reporting Practices and Personal Views

HN25 ‘Kevin Douglas’ infiltrated the Troops Out Movement (TOM) in Haringey, but took five months to make contact, claiming there were no public events to attend in that period.

Once embedded, he provided extensive reporting on the group’s activities (including the people active at London and national level), membership numbers, and potential physical threats against TOM members by right-wing groups.

Notably, HN25 ‘Kevin Douglas’ admitted that the Troops Out Movement did not pose any kind of public order risk:

‘They would not be the aggressors’

Despite this, he continued to report on their activities, as well as on various justice campaigns, including those for the Tottenham Three, Birmingham Six, and Guildford Four, linking them with terrorism in his reports, despite the fact that all those concerned were innocent.

He attended and reported on a local public meeting of over 500 people, including a disparaging summary of a speech by local MP Bernie Grant.

He reported on the Broadwater Farm Defence Campaign, referring to the Tottenham Three as the ‘convicted murderers of Police Constable Blakelock’ even though the convictions were quashed in 1991.

He was also concerned that TOM and the various defence campaigns seemed to be communicating with and supporting each other.

When questioned about this he claimed that it was ‘all part of what was seen as an anti-colonial broad front, Ireland being the original colony in the view of Troops Out Movement’.

Challenged on his dismissive tone, he said he makes ‘no apology for that’. He also admitted, without irony, that part of his role was to ‘prevent embarrassment… not just to the Government but to the United Kingdom’.

Despite the Metropolitan Police apologising at the start of these hearings for this kind of unacceptable reporting on justice campaigns, HN25 ‘Kevin Douglas’ claimed he saw no problem with it, not even with his continued reporting on those groups after the Court of Appeal granted the release of those imprisoned as they had been framed by police.

In his first witness statement to the Inquiry he had justified spying on justice campaigns by suggesting it would ‘make the job of the uniformed officers more straightforward’, a sentiment he defended when challenged.

Sexual Relationships

A significant part of the questioning was about his 2013 statement to Operation Herne, the police’s internal inquiry into spycops before the Undercover Policing Inquiry was ordered. In it, he admitted to regular occurrences of sleeping with women and suggested senior management knew about it.

Some of his reports included sexist comments about women activists, described as ‘attractive’ or ‘well-built’.

‘There was a regular occurrence in respect of sleeping with women. It wasn’t regarded as wrong at the time, the person would have to undertake a dynamic risk assessment. I feel sorry for the woman Bob [Lambert, HN10] slept with who was not a target as such’

In fact HN10 Bob Lambert had four sexual relationships, including fathering a child.

In that statement to Operaton Herne, HN25 ‘Kevin Douglas’ had written:

‘The Senior Management Team probably suspected that these relationships took place and that it was not an issue. Most knew of it “in play”. There was nothing direct in place as to not conduct such practices’

He claimed he was mixed up with Bob Lambert to show Lambert wasn’t a rogue officer. He suggested officers used sex to gather intelligence, a justification he later denied.

He told Operation Herne:

‘I think bringing a child into the world as part of an operational decision is wrong’

HN25 ‘Kevin Douglas’ was asked about the accusation that HN10 Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’ had placed a timed incendiary device in the Harrow branch of Debenhams while undercover in an animal rights group opposed to the sale of fur. The incident resulted in major damage.

HN25 ‘Kevin Douglas’ claimed he wasn’t privy to discussions about the incident, but was aware of Lambert’s infiltration of the Animal Liberation Front. He noted that HN10 Bob Lambert was the only SDS officer who visited a certain Special Branch building in Vincent Square and that he had to check Lambert wasn’t being followed.

HN25 ‘Kevin Douglas’ also mentioned HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’ had a fraudulent sexual relationship with Helen Steel, learning about it through gossip.

He wasn’t particularly surprised, outrageously claiming that it was to be expected because:

‘it was more the area he was employed… a place of squats, of that sort of living’

He backtracked on some of these statements during his time in the witness box. He insisted that Operation Herne ‘was meant to go nowhere fast, and not leave the room’, ie never see the light of day.

This is very revealing, as Operation Herne, the police investigation into undercover policing, has long been criticised by victims of undercover policing as essentially a cover up allowing the police to ‘mark their own homework’.

HN25 ‘Kevin Douglas’ appeared visibly stressed when confronted with his Herne statement, talking over the questions, moving back and forth in his seat, sweating, and red-faced in his anxiety to retract the answers he gave in 2013.

Post-Deployment Activities and Reflections

After his deployment, HN25 ‘Kevin Douglas’ mentored new officers for over six years. He believed it was important to pass on knowledge:

‘If you feel you can do some good, and they think you’ve got something relevant to say, I think it is important that you do that’

His mentoring of the first undercover officer went well, but he experienced difficulties with the second and third, possibly due to concerns about the official caveat that information obtained could be passed to senior management.

Reflecting on the impact of undercover work, HN25 ‘Kevin Douglas’ described the difficulty of living a double life:

‘You live in a world of lies. It’s not easy to do and it’s not pleasant to do… the problem being undercover is you tell one lie, you have to tell 100 lies’

We are not entirely sure how he resolved this against his previously expressed view that it would be a huge dislocation to have a police officer who didn’t believe that honesty is the right course.

Tuesday 23rd July (Day 12)

Click here for video, transcripts and written evidence

The Case of HN95 Stefan Scutt

The Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) deployment of HN95 Stefan Scutt ‘Stefan Wesolowski’ was marred by significant ethical and operational breaches.

He reported on the Socialist Workers’ Party in Hackney and related campaigns, including the year-long industrial dispute in Wapping against the mass sacking of 5,000 printworkers by newspaper bosses.

He informed another officer about sexual misconduct by an undercover operative, hinting at the widespread nature of such unethical behaviour.

After his withdrawal, it was claimed that Scutt had apparently embellished his army career on his application to the SDS (claiming he’d been involved in intelligence in Northern Ireland), was allegedly secretly living with a partner and children in Norfolk while supposedly undercover, falsified entries in his SDS rent book, and claimed overtime he wasn’t entitled to.

In May 1988, Superintendent Evans identified the root of Scutt’s problems as a breakdown in his relationship with his superior officer Detective Inspector HN109, noting they were ‘not complementary characters’.

Despite these issues, HN10 Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’, HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’, and HN8 (names withheld) defended Scutt and sought more time for his withdrawal, revealing the unit’s reluctance to address internal problems.

The toxic atmosphere within the unit was further exemplified by reports of HN10 Bob Lambert physically confronting HN109, allegedly pushing him against a wall and making threats if he didn’t leave ‘Stef’ alone.

Mental Health Crisis and Mishandling

Following his withdrawal, Scutt experienced a significant mental health crisis. Superintendent Evans described him as ‘looking grey and drawn’ and ‘quite ill with worry’.

Scutt was removed from the list of authorised firearms officers and subsequently went absent without leave. He was eventually found disoriented in the grounds of York Cathedral, where he disclosed details about his deployments to uniformed officers.

Scutt was later diagnosed with an ‘alter ego problem’. However, management had intervened to protect the unit by insisting this diagnosis pre-dated his deployment.

In the face of these serious issues, Special Branch decided against disciplinary proceedings. DCS Parker justified this decision by arguing that it would be complicated to establish the facts and risked exposing the unit to unwelcome publicity. The events surrounding Scutt’s withdrawal were kept as quiet as possible. Though documents show the Director General of the Security Service was informed, a note from the agency shows:

‘the SDS consider this to be an internal matter only. They may decide to allude to it in their 1988 annual report but were very exercised at the idea of the problem being brought to the immediate attention of the Home Office’

Scutt’s case had broader implications for the SDS. The controversy was followed by changes in how the SDS was funded, with the Home Office switching from annual to rolling funding, effectively reducing oversight.

SDS managers feared that if details of Scutt’s case became public, it could lead to the unit being shut down. We note that the Inquiry, in its Interim Report in 2023, has already concluded that the unit should have been closed down anyway, way back in the early 1970s.

Live: HN90 ‘Mark Kerry’

HN90 ‘Mark Kerry’ testified about his infiltration of various Socialist Workers Party branches in South London in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Recruitment and Training

HN90 ‘Mark Kerry’ joined the Metropolitan Police in the early 1980s, serving in uniform before joining Special Branch in the mid-1980s. His path to the Special Demonstration Squad began with a casual conversation with a colleague in April 1988, highlighting the informal nature of SDS recruitment.

During his selection meeting, HN90 ‘Mark Kerry’ had expressed his views on protest:

‘I said that I believed that people had a right to protest, and I had no problem with that. However, because of the disorder that, you know, I had seen, I didn’t believe that protesters had perhaps the right to impact so much on other people’s lives’

Like HN25 ‘Kevin Douglas’, HN90 ‘Mark Kerry’ received minimal training for his role. He confirmed that there was ‘no formal course or training’ while inside the SDS. Instead, preparation for deployment involved regular meetings and conversations with experienced undercover officers and managers.

After his deployment, HN90 ‘Mark Kerry’ went on to serve as a mentor to undercover officers, attending training sessions to prepare for the role, including one with a psychologist. However, he felt the mentoring scheme had limitations:

‘we may have been ex-field officers but at the end of the day, we weren’t counsellors. So didn’t have, obviously, the benefit of psychologist training or something similar’

This lack of formal training and guidance is a recurring theme in evidence from officers in the SDS.

Stolen Identity

As was standard SDS practice, HN90 ‘Mark Kerry’ stole the identity of a dead child for his time undercover. He conducted research into the real Mark Kerry’s background, including visiting the area where the boy had lived.

‘It was simply so I could familiarise myself with the locality. So if at some point I should be asked on where I was born, et cetera, then I would at least be able to describe something of, you know, where I had been born and brought up’

Influence, Intrusion and Blackmail

HN90 ‘Mark Kerry’ first infiltrated the City of London Anti-Apartheid Group, who had a permanent 24hours-a-day protest outside the South African embassy.

He then infiltrated various Socialist Workers Party (SWP) branches, including Lambeth South, South-West London, Kingston, and Lambeth North. He played an active role in SWP activities, even helping to establish a new branch in Kingston.

As with colleagues who took roles of influence on the groups they spied on, he was at pains to downplay it. When questioned about the appropriateness of his level of involvement, he unconvincingly claimed:

‘my contribution would have made no difference to whether that group would have carried out that activity at Kingston or not’

His deep involvement in SWP activities included attending the party’s annual 2,000-strong rally/social gathering at Skegness, where he shared accommodation with other activists. He drove at least one activist to the event and rented a caravan with three others.

HN90 ‘Mark Kerry’ appeared to be completely oblivious to the inappropriateness of this, responding when asked ‘I just simply didn’t see it as an intrusion’

He provided extensive reporting on SWP activities and members’ personal lives. He consistently argued that all information was potentially valuable and that it was standard practice to report everything he could remember.

Asked about the necessity of reporting all this information, he responded

‘I think really I included everything that I thought was relevant to the character of that person, or to the physical appearance of that person’

His reports often included sensitive personal information. For example, one report from March 1992, detailed someone described as a ‘practising homosexual’ who was no longer a member of the SWP.

HN90 ‘Mark Kerry’ defended reporting such information:

‘It was relevant to report that this ex-member of the SWP went to events about “homosexual rights” despite the fact these events were not subversive of public order issues’

Most significantly, he acknowledged that a range of such personal information (including regarding sexuality and family issues) would be reported because:

‘this might be useful for anyone seeking to recruit [the person] as an informer’

When asked if it was within his remit to report such information, he responded:

‘Sometimes it was, yes’

He claimed someone had undertaken a ‘marriage of convenience’, and ‘this sort of information may have assisted with any efforts to recruit the individual as a source’, ie coerced into becoming a police informant.

The only possible conclusion of this shocking admission is that the SDS was routinely collecting such information on hundreds if not thousands of people to be potentially used by police or security services to threaten and blackmail vulnerable people into becoming informants.

It will be interesting to see how many future SDS witnesses, including managers, admit to this vile tactic.

The Poll Tax Demonstrations

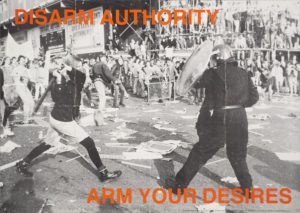

Poll Tax Riot poster – ‘Disarm Authority Arm Your Desires’ – designed & distributed by spycop John Dines to raise funds for those arrested

As the grassroots movement against the Government’s poll tax continued to grow hugely in 1989 and early 1990, SDS officers monitored the many local protests, especially the mass protests at local Town Halls setting the ‘rates’.

There was planned a national demonstration to Trafalgar Square on 31 March 1990, the day before the new tax was to be implemented. SDS officers met to pool their ‘intelligence’ on the numbers expected.

The SDS’s ability to provide such pre-demonstration estimates is regularly used to try to ‘justify’ its extensive and intrusive spying. The officers came up with an estimate of 15,000 people.

HN90 ‘Mark Kerry’ stated:

‘I said, personally, it was going to be as big as the CND demonstration of – I forget how many years before. So my estimate was probably around 30,000 people.’

In fact, over 200,000 attended. So much for SDS ‘intelligence’.

HN90 ‘Mark Kerry’ said that he was aware that fellow SDS officer HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’ had been arrested during what had turned into a riot in and around Trafalgar Square (Dines later boasted of the event, writing an article and making a poster)

HN90 ‘Mark Kerry’ recalled:

‘he had, I think, marbles in his pocket in the riot. I don’t know how that came to police notice, but I understand he was arrested’

HN90 explained that marbles could be thrown in front of police horses (to deter mounted charges).

‘Justification’?

Throughout his testimony, HN90 ‘Mark Kerry’ appeared to have no concept of the inappropriateness of police interfering in political processes. He defended the SDS operations as necessary for maintaining public order and assessing the potential for subversion.

‘I didn’t see that the SDS was trying to achieve a shutdown of political organisations, but more to monitor what was going on and to report back’

When questioned about reporting on democratically elected representatives, he responded

‘I was just simply reporting, you know, on their appearance at a public event and what they had to say. So I didn’t see that as any problem whatsoever’

Unlike some previous officers who expressed regret in hindsight, HN90 ‘Mark Kerry’ remained steadfast in his belief that all his actions and infiltrations were fully justified, even when viewed from today’s perspective. When asked if his infiltration of the Socialist Workers Party remained justifiable on public order grounds, he responded, ‘Yes, I do’.

Relationships with Management and MI5

Meetings between SDS managers and the Security Service were regular occurrences, with the Security Service providing assessments of the value of SDS intelligence. HN90 ‘Mark Kerry’ acknowledged regular contact with his managers and noted the Security Service’s interest in his deployment, describing them as ‘one of our main customers’.

The Security Service played a significant role in influencing targeting decisions for undercover officers, showing interest in specific groups and individuals, and making regular requests for information.

HN90 ‘Mark Kerry’ was aware of these interactions:

‘I knew right from the outset that the Security Service, you know, was an important customer, shall we say, of our intelligence reports’

Spying on the Lawrence Family

While working in C Squad in Special Branch after his deployment, HN90 ‘Mark Kerry’ admitted seeing SDS reports on the Stephen Lawrence family campaign, which was seeking justice for their son who was murdered by a gang of racists.

‘Yes, I – I do [recall seeing such reports], because that was – that was something that, um, obviously the Metropolitan Police were interested obviously in the murder and that question there, whether or not there was any extreme right wing involvement in that. So that was – so any reporting that concerned that campaign, I would sometimes see that material’

He claimed that such reports were ‘very, very, very rare’.

The Inquiry failed to question him further about this highly controversial issue, and one of the key controversies fundamental to the setting up of the whole undercover policing inquiry. We know that former SDS officer Peter Francis has stated that the SDS were spying on the family campaign, trying to ‘find dirt’ with which to smear them.

C Squad was clearly investigating if the racist assailants who murdered Stephen Lawrence had connections with right-wing political groups, and yet were getting the SDS secret reports on the family campaign. Why were such reports written, and how were they used? Why did the police investigation fail to nail the murderers?

Wednesday 24th July (Day 13)

Click here for video, transcripts and written evidence

Live: HN56 ‘Alan Nicholson’

HN56 ‘Alan Nicholson’ was a notable witness as, unlike all the other officers giving evidence in open hearings about spying on the political left, he was deployed to infiltrate the far-right.

In 1990, he was sent to spy on the British National Party (BNP). His deployment was remarkably short lived, lasting less than a year, and therefore sits in sharp contrast to the officers who were deployed into left wing groups for years on end.

Bizarrely he was ordered by the SDS, backed by the Security Service, to join an inactive, even dormant, BNP branch in Loughton. Was this just a token deployment to pretend to ‘balance’ the widespread targeting of the left? Or was it more the case, as we had heard during the evidence in Tranche 1 of the hearings, that fascist groups weren’t infiltrated as they were ‘too violent’?

The testimony of HN56 ‘Alan Nicholson’ revealed the SDS as a highly secretive unit, even within the Metropolitan Police. He described first noticing SDS officers as ‘strange people’ with ‘long hair and beards’ appearing in the office, but ‘nobody would really talk about it’.

The selection process was equally opaque, ‘unlike any sort of selection board I had been through before’.

Once in the SDS, officers worked largely in isolation. Training was informal, as HN56 ‘Alan Nicholson’ described:

‘I believe all of my pre-deployment knowledge was gained through discussions with the officers already in the field’

These discussions often occurred during twice-weekly meetings. HN56 ‘Alan Nicholson’ emphasised the lack of structure as he corrected the implications of the Inquiry’s questioning:

‘Unfortunately you make it sound like a lecture. It isn’t, it’s like a cup of coffee chat’

HN56 ‘Alan Nicholson’ did not steal a dead child’s identity, contrasting with a significant proportion of earlier officers. He also revealed the interesting detail that SDS officers did not know each other’s cover names and that it was considered ‘taboo’ to ask.

Infiltration of Far-Right Groups

The deployment of HN56 ‘Alan Nicholson’ into the British National Party provided insights into the SDS’s approach (or lack of it) to far-right groups.

He seems to have been selected for this role due to being ‘a black belt in Karate’.

At a national BNP rally, he reported hearing a speech claiming that ‘obviously a large number of police understood the sentiments if not supported the British National Party’” and that:

‘if these officers did not soon cast off their uniforms and throw in their lot with the British National Party and join in the struggle for racial purity they would find themselves the targets of British National Party wrath when it finally achieved power – an hypothesis which was greeted by almost deafening agreement in the form of applause by the audience’.

HN56 ‘Alan Nicholson’ also reported on a speech by BNP chairman John Tyndall, who said that the Metropolitan Police Commissioner ‘was no more than a puppet dancing to the tune of the [Jewish] British Board of Deputies’.

Despite the BNP’s well known anti-semitism, HN56 ‘Alan Nicholson’ was renting a flat from a Jewish family. BNP members visited him there, and the Inquiry questioned him about the potential risk to his landlords – he said that the visitors were unaware of the situation.

He admitted to witnessing a brazen physical assault on a left wing supporter by a BNP activist at a march without reporting it, rationalising, ‘there was no point in me trying to report’.

When questioned further, he attempted to justify his inaction:

‘Well, there may have been a crime, whether it was a common assault, actual bodily harm or grievous bodily harm, I couldn’t tell’

He later said that he had ‘significant discretion’ in what he reported, but also claimed he would report ‘anything, really, that was going on that was of interest to the police’.

The deployment of HN56 ‘Alan Nicholson’ focused on the Loughton branch of the British National Party, which he described as ‘moribund’, maybe just one or two activists selling the BNP paper.

This led to periods of limited reporting, causing some concern among his managers about his productivity. He explained:

‘they were not doing anything… I found it quite boring to be perfectly honest’.

He told the Inquiry that the BNP members he interacted with were ‘quite a law abiding bunch of people’ and that he didn’t witness organised attacks, which contrasts somewhat with his statements about the broader far-right being prone to violence.

At a BNP ‘Rights for Whites’ demonstration HN56 ‘Alan Nicholson’ saw that one of the leaders was talking conspiratorially with a member of the Loughton branch, and pointing over at him. He believed that he may have been identified as a policeman. He reported that he was followed twice whist driving in his car.

After being asked by the SDS to attend a BNP branch meeting elsewhere in East London, he refused as he felt was too dangerous. ‘I was concerned that I could have been killed’, he explained.

‘It would have been suspicious for a Loughton British National Party member to turn up to another group’s meeting out of the blue’

HN56 ‘Alan Nicholson’ said that after this the managers turned on him.

This, combined with his earlier safety concerns, led to his unilateral decision to withdraw from the operation. HN56 ‘Alan Nicholson’ ended his own deployment, cleared out his operational flat and reverted to his usual appearance. SDS managers were ‘horrified’ about this, but could do nothing.

He was questioned about an incident from his written evidence where he described a ‘complicated relationship’ with one of the other SDS officers:. He suspected that the colleague done things which could have exposed him. The colleague had asked HN56 ‘Alan Nicholson’ for his cover name at a biweekly meeting. Afterwards two other officers had expressed their shock, because asking for someone’s cover name was taboo.

The implication here is that an officer with right wing sympathies, or maybe an axe to grind, may have sought to expose HN56 ‘Alan Nicholson’ to the BNP.

Sexual Relationships

His testimony highlighted numerous ethical complexities. He admitted to wearing a wedding ring partly as a ‘deterrent’ to romantic entanglements in his cover identity. However, he claimed ignorance of any sexual relationships between SDS officers and targets until media revelations years later:

‘I had never, ever heard of a relationship with a woman’

This claim seems at odds with the widespread nature of such relationships later revealed. When asked about his reaction to eventually learning about HN10 Bob Lambert‘s abuses, he said he had been ‘astonished’:

‘It just seemed ridiculous that he could have been so stupid and irresponsible, and, if you want, immoral. That he could do that to his family’

Nonetheless, he described Lambert as ‘a very capable police officer… a very intelligent man… the most professional SDS officer ever’

That’s certainly a novel view of one of the most controversial of all the spycops.

Management, Oversight and the Impact of Undercover Work

Like so many officers at the Inquiry, the evidence of HN56 ‘Alan Nicholson’ illuminated significant failings in SDS management. He provided insights into his own relationship with other officers and managers. He described HN109’s management style as ‘very difficult’ and said he ‘mistrusted him’.

In contrast, he praised Detective Chief Inspector Martin Gray as one of the best managers he ever had. About Chris Hyde, he said he was ‘one of the boys… not really a very good manager’. When asked if he felt supported after his deployment ended, HN56 ‘Alan Nicholson’ replied simply ‘not at all, no’.

He highlighted the lack of formal support structures within the SDS, both during and after deployments. His experiences suggest a unit that often operated on informal practices and personal relationships, rather than established protocols. Regarding welfare support, he said:

‘There was no welfare or support for me as a former undercover officer. With hindsight, it was not adequate for my needs although I was able to quash any rumours about my deployment’

When he ended his own deployment, HN56 ‘Alan Nicholson’ felt unsupported by management, describing ‘a couple of unpleasant months at work’ where he was ‘treated with some disdain by some colleagues’.

He left us with an impression of a culture where management was quick to blame individual officers rather than examine systemic issues, recounting a particularly telling interaction with superintendent in the corridor in Special Branch:

‘he shook my hand and said “it takes a brave man to admit that he is not up to the job” ‘

The psychological toll of undercover work was evident in the evidence HN56 ‘Alan Nicholson’, which highlights the intense pressure and isolation felt by undercover officers.

He mentioned officers who left the police immediately after their deployments, and spoke about one officer, HN4, who ‘took to drink’ following his undercover work. When asked about HN4’s struggles, HN56 said ‘it was obvious. He got into trouble’.

His account of how fellow officers confronted HN4 about a drink driving arrest was interesting, revealing a deeply dysfunctional approach to internal discipline. He described a ‘self-appointed “Court of the Star Chamber” ‘ in which HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’ and another officer asked managers to leave the room (which they did):

‘they were interrogating HN4 over his behaviour… and it wasn’t just the drink drive’

HN56 ‘Alan Nicholson’ also expressed scepticism about HN5 John Dines claiming to having been beaten up by police following being arrested at the Trafalgar Square poll tax demonstration.

He was present when HN5 John Dines came into the SDS office and said it looked like he’d faked it in a bid for martyrdom credibility:

‘The injuries that he sustained, in my mind, were not consistent with having been beaten up in the back of a police van. In other words, they were self-inflicted, in my opinion. The injuries I witnessed on his face did not resemble being battered’

Taken as a whole, his evidence suggested a toxic culture where officers (for example Dines) took discipline into their own hands and may have exaggerated incidents for ‘glory’ or ‘notoriety’.

While he denied any difference in attitudes towards women or racial minorities between police and non-police organisations, he belied this by suggesting that officers who joined the police young were ‘less likely to recognise’ sexist behaviour as problematic, describing it as ‘the norm’ in some instances. He attributed his own different perspective to his background:

‘Because I think – because I was a late joiner, I was not moulded by the Metropolitan Police like a young man can be when they join at 18’

This is an implicit admission that sexism and racism are normalised and instilled by the police. It is an institutional problem.

Financial Incentives

Documents showed HN56 ‘Alan Nicholson’ received significant overtime payments of over £1000 per month.

When asked if this was a substantial amount in 1990, he confirmed ‘yes, huge, yes’. He insisted money was not an incentive, because ‘if it had been an incentive I would have stayed on’.

Nevertheless, the substantial sums involved raise questions about other officers motivations for undertaking, and seeking to extend, undercover operations and continue useless, potentially traumatic or ethically dubious deployments.

The fact that this officer had collected so much money for infrequent reports and failure to infiltrate any group properly shows how easily the overtime and lack of oversight could add up to a cushy scam.

Thursday 25th July (Day 14)

Click here for video, transcripts and written evidence

Live: Lindsey German

Socialist Workers’ Party

The final day of the week’s hearings featured testimony from Lindsey German, for 30 years a pivotal figure in the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) and currently the convener of the Stop the War Coalition. German’s testimony provided a crucial counterpoint to police narratives heard earlier in the week.

German was elected to the SWP central committee in 1979 and remained in the role throughout the Inquiry’s Tranche 2 period (1983-1992). She was involved in organising meetings, editing publications, and supporting campaigns, demonstrations and strikes.

German said that the committee met weekly to discuss strategic matters. She also mentioned her regular attendance at national demonstrations, though she was less frequent at local protests. She described how the SWP also supported a range of social justice causes, from the Poll Tax protests to the campaign against the 1994 Criminal Justice Bill.

She discussed the annual ‘Marxism’ events organised by the SWP, describing them as public, academic gatherings that attracted a wide range of people, over 6,000 attendees, including many non-SWP members.

2,000 people, including children and many non-members, also attended the SWP’s annual gathering at Skegness. She bluntly condemned the heavy SDS surveillance of all these events:

‘The idea that there was any need for any kind of undercover policing is just ludicrous really’

SWP Activities and Police Mischaracterisations

A significant part of German’s testimony was dedicated to examining documents like the Security Service’s ‘Brief Guide to Subversion in Great Britain’ from 1985 and 1995, which described the SWP as a Trotskyite organisation advocating for the overthrow of the capitalist system, aiming to replace it with workers’ councils.

German agreed with the general description but emphasised the SWP’s commitment to democracy:

‘We believed that you could only achieve socialism, I still do believe this, by an organic movement based on working class people organising themselves, and therefore presenting an alternative to existing government’

German strongly rejected characterisations of SWP members as aggressive or disruptive in police reports.

She pointed out the inaccuracies in many of the reports, and their often derogatory comments – for example she criticised an SDS officer’s description of Wayman Bennett, a university-educated black man, who had been characterised as being ‘not particularly intelligent’.

The relaunch of the Anti-Nazi League (ANL) in the early 1990’s was also addressed with German explaining the SWP’s role in this, emphasising that while the SWP initiated the relaunch, the ANL was a broad organisation with many non-SWP members.

German addressed SDS officer claims about the alleged formation of a group of ‘hitters’ within the SWP or ANL – a supposed group of activists set up to physically defend events from fascist attacks. She denied any knowledge or approval of such a group:

‘I don’t think that would have been sanctioned by the central committee’

The Welling Demonstration and Police Tactics

A significant portion of German’s testimony focused on the mass anti-BNP demonstration at Welling on 16 October 1993. It was organised by a range of groups, and up to 40,000 attended, calling for the closure of a BNP ‘bookshop’ in the area.

The establishment of this ‘bookshop’, in reality an organising base for racists and fascists, had led to a massive growth in racist attacks on local black residents, including murders (for example of Stephen Lawrence).

German explained how the police had banned the march from going past the ‘bookshop’, and agreed an alternative route with the organisers. However, on the day the police halted and surrounded the march at a junction, and then attacked it.

She described the events as a ‘medieval battle’, noting the aggressive police presence, including 83 mounted officers, which was more than twice the number used at the notorious Orgreave miners’ demonstration attacked by police in 1984.

German recounted how the police cordoned off all exits, creating a chaotic and dangerous environment.

A fellow SWP Central Committee member, Julie Waterson, was badly injured.

‘People were injured by police truncheons in numerous police charges. It was extremely fortunate that no one died from police charges that day’

This view was based on her personal experiences, having been present at the 1974 Red Lion Square anti-fascist protest when Kevin Gately had been killed by police, and at a 2001 protest in Genoa, Italy, where anti-capitalist demonstrator Carlo Giuliani was shot dead by police.

German dismissed allegations that the SWP planned to incite violence at the demonstration, including the supposed intention to burn down the BNP bookshop. She explained that the police’s violent tactics, not the demonstrators’ actions, led to injuries and chaos. German emphasised the pattern of police instigating violence at certain demonstrations, a recurring theme in her testimony.

German’s testimony also covered the SWP’s support for various justice campaigns, including those for the Tottenham Three, Joy Gardner, Brian Douglas, and Stephen Lawrence. She explained that the SWP’s involvement was driven by their politics, which opposed injustice and supported those wronged by the system. German firmly rejected SDS slurs that the SWP supported these campaigns for their own political gain.

Reflections on Impact of Undercover Policing and Social Justice

German’s testimony concluded with broader reflections on the role of policing in society and the importance of social justice movements. She discussed the SWP’s view on the role of the police in maintaining capitalist power structures and defended the SWP’s support for industrial disputes, emphasising their role in standing up for better wages and working conditions, and trade union rights.

German was critical of the undercover policing operations and the reports they produced:

‘there is such a level of self-promotion, aggrandisement and inaccuracy about these reports’

She described the emotional toll of undercover policing on activist groups, including a pervasive sense of mistrust and suspicion that lingered long after the operations ended, undermining the work of social justice organisations.

German also touched on the changing nature of protest and political activism over the years, noting the impact of events like the Poll Tax protests and the rise of the BNP on SWP membership and activities.

Her testimony provided valuable historical context for understanding the political climate in which the SDS operated and the motivations of the groups and campaigns they targeted.