UCPI Daily Report, 13 May 2021

Tranche 1, Phase 2, Day 16

13 May 2021

Summary of evidence:

‘Phil Cooper’ (HN155, 1979-83)

Risk assessors of ‘Phil Cooper’: David Reid & Brian Lockie

‘Michael James’ (HN96, 1978-83)

!['Spycops Inquiry Give Us Our Files' banner at the notorious Stoke Newington police station where Colin Roach was killed. [Pic: David Mirzoeff & Artwork: Art Against Blacklisting Collective]](http://campaignopposingpolicesurveillance.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/stoke_newington_police_station_02-680x453.jpg)

‘Spycops Inquiry Give Us Our Files’ banner at the notorious Stoke Newington police station where Colin Roach was killed. [Pic: David Mirzoeff & Artwork: Art Against Blacklisting Collective]

It heard evidence from two undercover officers who infiltrated the Socialist Workers Party, Troops Out Movement, the Right to Work campaign and Waltham Forest Anti-Nuclear Campaign in the late 1970s. Both were elected as treasurers of groups they spied on.

‘Phil Cooper’

(HN155, 1979-83)

‘Phil Cooper‘ (HN155, 1979-83) is not being called to give oral evidence due to his current state of health. However, he has previously provided an updated and amended written statement.

The reporting obtained by the Inquiry shows that Cooper’s initial involvement was with the Waltham Forest Anti-Nuclear Campaign (WFANC), before moving on to the Socialist Workers Party (SWP). With the latter organisation he focused on the Right to Work Campaign, becoming its national treasurer ( a position previously held by his spycop colleague HN80 ‘Colin Clark’).

Cooper recalls that he joined the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) before October 1979 and spent time working in the back office before being deployed undercover.

The first report which can attributed to him with confidence dates to April 1980 [UCPI0000013893]. It notes, however, his election as treasurer at the inaugural meeting of WFANC in February 1980, which suggests he had been deployed for a period before this date. His deployment ended in January 1984.

PREVIOUS UNDERCOVER WORK

Before joining the SDS, Cooper had undertaken ‘a fair amount’ of undercover police work. This as part of the Metropolitan Police Special Branch’s ‘B’ Squad which covered ‘Irish matters’. This work included adopting a cover identity, aspects of which he utilised within his SDS deployment. His story was that he had grown up in Liverpool and had been in the Merchant Navy.

In advance of his SDS deployment, he recalls visiting Liverpool to build his ‘legend’. Cooper accepts that he is likely to have stolen a deceased child’s identity as it was the usual process at the time, although the Inquiry has not been able to identify the individual it was stolen from.

WALTHAM FOREST ANTI-NUCLEAR CAMPAIGN

Cooper adopted two positions of responsibility within the groups he reported on. The first, treasurer of the Waltham Forest Anti-Nuclear Campaign, was at the very start of his deployment. The second role, also as treasurer for the Right to Work Campaign, came later in January 1982.

It seems likely that through this, Cooper also became involved in the campaign opposing the construction of a nuclear power plant at Torness, Scotland, and probably attended the Torness Alliance conference in Oxford in July 1980 [UCPI0000014093].

Although he doubts that the reports on this subject are necessarily his, it seems likely that he attended a protest at the site in the course of his deployment.

RIGHT TO WORK CAMPAIGN

The first example of an SWP report which bears Cooper’s name is from October 1980 [UCPI0000014591]. He began reporting on the SWP-aligned Right to Work Campaign some months after the start of his deployment. He explains that the campaign:

‘was of interest to the SDS because it involved large numbers of people on marches lasting a number of days. Hundreds or thousands of local activists would join the march along the way, which included Marxists and anarchists…

‘it was important to provide intelligence to allow local constabularies to assess the risk of public disorder and ensure an appropriate police presence.’

A comprehensive report [UCPI0000014610] records the events of the 1980 march from Port Talbot in detail, culminating in a demonstration outside the Conservative Party Conference in Brighton in October, is likely to be attributable to other undercovers, ‘Vince Miller‘ (HN354, 1976-79) and ‘Colin Clark’ (HN80, 1977-82). Clark’s withdrawal appears to have coincided with the start of Cooper’s deployment, and his deployment may have been extended to ensure this overlap took place.

Right to Work march at the Conservative Party conference, Brighton, October 1980

Also of note is an April 1981 report from Cooper concerning a National Front counter-march [UCPI0000016599]. It mentions ‘Madeleine’ who had been targeted by Miller for a relationship and who gave testimony to the Inquiry earlier in the week.

From 1982 onwards, Cooper seems to be the only SDS officer involved in the Right to Work campaign. He became National Treasurer in January 1982, with control over the bank account [UCPI0000018091].

He was able to submit detailed reports on the arrangements for the intended 1982 march, which was latterly modified to become a picket of the Conservative Party Conference, which was attended by 400-500 people.

He managed to obtain private documents and correspondence with the organisers (one of whom was the serving MP Ernie Roberts) [UCPI0000017202], and the personal bank account details of those concerned.

AT THE HEART OF THE SWP

As ‘Colin Clark’ (HN80, 1977-82) had done before him, Cooper rapidly rose through the SWP ranks and gained access to the their headquarters. He provided a detailed floor-plan of the office, including the location of his desk as the Right to Work treasurer.

This also allowed Cooper to provide information to the Security Service (MI5) on the state of SWP membership records, and in 1982 they asked him to pass on any old cards should he get access to them made, [UCPI0000027448]. Similarly, he was able to respond to requests from MI5 for the technical details of the SWP computer and passed on membership details contained therein [UCPI0000016862, UCPI0000016946, UCPI0000020522].

Cooper was also able to provide intelligence on the personal lives and circumstances of members of the SWP Central Committee and those close to them.

He attended the SWP’s annual national delegate conference and rally at Skegness between 1981 and 1983 and provided detailed reports on each occasion. He attended alongside ‘Colin Clark’ in 1981, when both were listed as part of the conference administrative staff.

In 1982 and 1983, Cooper was trusted enough to gather the entrance money which provided him with an 18 page list of 1983 attendees, which he included in his report that was passed to MI5 [UCPI0000018180].

In respect of the 1983 report, it was noted by MI5 that ‘the SDS office [was] still groaning under the weight of Cooper’s report’ and it was subsequently considered to be of significant value to the Special Branch and MI5 alike [UCPI0000028728, MPS-0730009, MPS-0735901]. Cooper thinks he received one of two commendations for this work.

Towards the end of his deployment, in November 1983 Cooper appears to have submitted a report on a former member of the SWP Central Committee who had ‘obtained false employment references which he hopes will hide his political activities from prospective employers’ [UCPI0000020466].

REPORTING ON SCHOOL KIDS

Cooper may have submitted reporting on the National Union of School Students, and school-aged children more generally, in 1981 [UCPI0000016563].

He notes that the fact that this involved reporting on children ‘was not considered at the time, but probably would not have involved myself’. Spying on children appears to have been commonplace.

MI5 TASKINGS

In late 1981, several MI5 ‘notes for file’ record requests were made of SDS managers, asking for information to be acquired by SDS officers who had access to the SWP headquarters [UCPI0000027529, UCPI0000028837, UCPI0000027532, UCPI0000027533]. This is very likely to have been directed towards Cooper or Clark, and represents a clear trend at this time of MI5 requests made of SDS officers.

Similarly, by autumn 1982, Cooper was able to answer a detailed request for information from MI5 on SWP structure and branches.

DEPLOYMENT PROBLEMS

In a meeting with MI5 in July 1982, ‘Sean Lynch’ (HN68, undercover 1968-74 but by then an SDS manager) is recorded as expressing ‘serious doubts about the performance’ of Cooper. This relates to the officer’s failure to pay child maintenance, and an incident when he left his cover vehicle outside his real home address.

A subsequent note [UCPI0000027446], records that Lynch:

‘is still very worried because Cooper’s position within the Right to Work Movement gives him regular access to Ernie Roberts MP and meetings at the House of Commons’.

In contrast, Cooper himself does not recall any contact with Roberts, and considers any involvement must have been limited in nature.

PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSESSMENTS

The psychological assessors who spoke to Cooper ahead of the Inquiry say that he is not a reliable witness due to being both highly suggestible, and wanting to avoid subjects that would mean revisiting traumatic experiences [UCPI0000034361], [UCPI0000034360].

We have already heard evidence in this phase of the Inquiry from Cooper’s fellow undercovers ‘Graham Coates’ (HN304, 1975-79) and ‘Vince Miller‘ (HN354, 1976-79). Neither were complementary, with Coates specifically alleging that Cooper fiddled the expenses and Clark saying that he got into ‘all kind of scrapes’.

When it was put to them that Cooper had sex with an activist whilst undercover, they both said that this did not surprise them. Coates said that Cooper was a ‘very charming, easy-going, light-hearted individual’ who found it easy to strike up friendships, and probably would have had ‘small to no’ qualms when it came to ‘accepting an offer of sex’ while undercover.

CAR CRASH

During his deployment, Cooper was involved in a car accident. Documents obtained by the Inquiry suggest he reported this to the police using his cover identity.

In his defence, Cooper said he did so as the car was registered in his cover identity, while he can’t recall if any consideration were given to the lawfulness of this course of action.

FORCED OR PLANNED EXIT?

Cooper’s deployment came to an end at around the time of a telephone call in December 1983 between two members of the SWP [UCPI0000028712]. A transcript of this call says his cover was blown with the group, and that there had previously been suspicions regarding him.

Cooper disputes that this call led to his withdrawal, and claims that it was in fact his exit strategy that caused the conversation to take place. He also recalls some concern from senior managers regarding his possible compromise having an effect on future intelligence and their careers:

‘I felt that some of the senior officers were more concerned about losing intelligence and repercussions for their career rather than concern for my safety or welfare’.

He notes that they were ‘prone to panic when issues [such as this] occurred’, in contrast to his immediate managers and previous unit head ‘Sean Lynch’.

Cooper explains that he went through a divorce during his time in the SDS, and suggests that his deployment was a ‘significant contributory factor in this regard’.

The impact of his deployment does not appear to have ended with his withdrawal. He notes that:

‘The effects are quite deep-rooted and have probably made me more of an insular and secretive person’.

‘PLAYING THE SDS CARD’

Mike Chitty undercover in the 1980s

The Inquiry released a sixty page report from 1994 [MPS-0726956] written by SDS boss Bob Lambert (HN10, undercover 1984-89) concerning undercover officer Mike Chitty (HN11, 1983-87), several years after Cooper had left the Metropolitan Police.

As ‘Mike Blake’, Chitty had infiltrated animal rights groups. Two years after his deployment ended, he returned to the social scene around the animal rights group he’d infiltrated.

He was eventually spotted by another SDS undercover, thought to be Andy Coles, and reported to his former squad. (This is recounted in detail in the Rob Evans and Paul Lewis book, Undercover: The True Story of Britain’s Secret Police.)

Suspended and subject to an investigation, Chitty resorted to threatening to expose the SDS and bring it down if he was disciplined. In his report, Lambert says that Cooper assisted Chitty.

Lambert’s report describes how Cooper himself had ‘played the SDS card’ in 1985 when he was facing dismissal from the police:

‘[Cooper]…was dismissed from the police service for assault. Immediately thereafter he wrote a letter to Commander Operations threatening to expose the SDS operation to the press if the decision was not overturned. Subsequently, the decision was reversed on appeal and [Cooper] left the service with an ill health pension’.

Lambert alleges that Cooper wrote to a Special Branch commander threatening to expose the SDS. Lambert describes this as:

‘the lowest point in the twenty-five-year history of the SDS.’

Given what we now know about the SDS and Lambert’s own undercover deployment – in which he fathered a child, co-wrote the McLibel leaflet that triggered the longest trial in English history, & allegedly burned down a department store – this seems to be something of an exaggerated claim.

Lambert writes that Cooper had:

‘convinced his psychiatrist… that he was suffering from “Stockholm Syndrome”, rather than, say, merely calculated, selfish and devious behaviour.’

He goes on to describe Cooper as:

‘A disgraced former SDS officer who showed a willingness to jeopardize the safe running of the SDS operation… selfish, arrogant, disloyal both professionally and domestically.’

Bob Lambert, 2013

This is a parallel opinion to the SDS’ belief that any group supporting another must be secretly motivated by a selfish and devious takeover bid, rather than actual solidarity. It seems that, living in a world of duplicity, secrecy and power games, spycops and spooks cannot conceive of people acting outside of such urges. So it’s no surprise to see spycop Lambert feels fully confident in dismissing the professional opinion of a psychiatrist and instead imposing the motives that have ruled his own behaviour.

Lambert himself should not be considered a reliable witness in Cooper’s case. Both the letter and threats to expose the SDS are denied by Cooper, who says he never met Lambert, so the report cannot be based on any personal knowledge of him.

SEXUAL RELATIONSHIPS

There remains a significant dispute of whether Cooper told the Undercover Policing Inquiry’s risk assessors that he engaged in sexual activity whilst he was deployed.

The Metropolitan Police employed them to assess the risk to former undercover officers if any aspect of their identity was revealed. The risk assessment prepared in late 2017 recorded that Cooper accepted that he had had two or three encounters with women, and the circumstances in which they took place [MPS-0746710].

Both the author, David Reid, and the second risk assessor, Brian Lockie, were left with the impression that Cooper was describing his own experiences whilst deployed [UCPI0000034397].

In contrast, Cooper suggests both misinterpreted his comments, saying that he:

‘was not as clear as I should have been about the dividing line between the specific, factual details of my particular deployment and more hypothetical comments about such deployments more generally.’

Cooper now denies engaging in a sexual relationship within the context of his deployment.

WITNESSES: DAVID REID AND BRIAN LOCKIE (RISK ASSESSORS)

The last witnesses to appear at the Tranche 1 Phase 2 hearings of the Inquiry were the two risk assessors in question, David Reid [MPS-0746378] and Brian Lockie [MPS-0747533]. They were called by lawyers representing a number of other undercover officers, including Cooper.

Questioned by the Inquiry, they gave highly technical accounts of the risk assessment process and of their interview of Cooper.

Both were asked to explain some alleged factual errors they made regarding their risk assessment for other officers. This seemed to aim at undermining the accuracy of their recollections of what Cooper said about the sexual encounters he had.

In essence, both Reid and Lockie’s testimony reaffirmed that what they had recorded Cooper saying was correct, although they conceded that they were ‘not infallible’.

Also of note was that it was learned that the risk assessment process had been an evolving one, with protocols and procedures changing as they went along to react from lessons learned.

It is unclear how this impacts on the earlier risk assessments, which were used to justify restriction orders over the publication of names of SDS undercovers.

Written supplemented witness statement of Phil Cooper

Written witness statement of Brian Lockie

Written witness statement of David Reid

‘Michael James’

(HN96, 1978-83)

‘Michael James‘ (HN96, 1978-83) infiltrated the Socialist Workers Party and Troops Out Movement. He occupied a senior role in the latter organisation in the early 1980s.

James’ evidence was a long and somewhat torturous process, often never quite addressing directly the questions being asked. Rather, he would repeat what the information was, but say he did not know the reason why it was done or recorded.

There was clear frustration as different points were covered and responded to with the same set of stock answers. To add to the annoyance, James often suggested to the Inquiry questions that he felt should be asked. So, while a lot of material was reviewed, insight and facts were often thin on the ground.

We do have to applaud Inquiry counsel Steven Gray for presenting the material in such a way that cut through James’ repeated shambling around answers, and exposed the rambling claims for the nonsense they were.

JOINING THE SDS

James did know of the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) before he was asked to join, and applied by expressing interest to Chief Superintendent Geoff Craft, who oversaw the squad. He had an informal face to face interview with Craft, but did not hear anything for a while.

Rather, James discovered by accident that he had been accepted, when running into a colleague going to a police exam. It would be several months before he got the telephone call telling him to report for duty with the SDS. It is his understanding that he was informally checked out, with others in Special Branch being asked about him, including supervising officers:

‘I spoke to some of my colleagues there, who said, “Yes, we’d been asked what sort of chap you were”.’

A PREFERENCE FOR MARRIED MEN

As with almost all his SDS colleagues, James was married when he joined the Squad. The Inquiry was keen to probe the reasons for why the SDS managers preferred married officers as undercovers. James had said in his witness statement that:

‘One of the main dangers of the unit was over-involvement with the role. It was felt that if you had family at home, you would approach the job in a different way to a single man who had nothing other than work in their lives. The thinking was that having a personal life away from the job allowed you to retain an objective distance from your work and the group you were reporting on.’

He learned this from comments from his SDS managers – probably from Mike Ferguson, a former undercover himself.

There began a process which repeated throughout the Inquiry hearing, of long answers not directly addressing the point, and going into abstractions or tangents rather than giving clear factual answers.

For instance, if asked about what might have been management reasons, he would talk of his own approaches. When asked why management might have been interested in some details, he would deflect to his own understanding.

The Inquiry tried to unpick the phrases in the above quote with more specific questions, such as what was meant by ‘over-involvement’ and why single men would approach the job differently – would they’d be more prone to engaging in sexual relationships?

James said the risk was of an officer revealing themselves as an undercover. The preference for married officers as undercovers was rooted in the assumption that they would live a more balanced life and it was:

‘nothing to do with their sexual behaviour whilst doing that work.’

MANAGERS MEET HIS WIFE

James said he had thought it would be beneficial for his managers, Mike Ferguson and Angus McIntosh, to meet his wife. They thought this was a good idea and they met her before he was deployed into the field. It then became accepted practice after this.

They addressed concerns she had around the deployment, particularly in relation to communications. She wanted to be able to reach James when he was in the field, if need be, and was given a contact number.

That such had never been done before and came down to the fact no undercover had ever asked for it.

TRAINING

James appears to have been mentored in Socialist Workers Party infiltrations by another undercover ‘Geoff Wallace’ (HN296, 1975-78). James would catch up with him during the twice weekly meetings at the SDS safe-house to pick his brain and those of other officers.

He agreed that alcohol was occasionally consumed at these meetings; later there was a social as well as professional element to the gatherings.

James claimed there was an ‘unwritten rule’; no talking with other undercovers about their actual deployments. The Inquiry returned to this more than once, at one point referring to the recent testimony of ‘Graham Coates’ (HN304, 1975-79) who painted a different picture of this. James insisted the rule included talking with the other undercover he shared a flat with, even though they were friends.

He was advised not to become too deeply involved in the groups he would infiltrate, not to become a leader, not to become someone who was required to be available a lot:

‘A willing worker rather than a leading light. That was some very sound advice I used the rest of my time.’

On personal relationships with targets, his mentor Wallace said be:

‘friendly and helpful, but not getting too close to members of the group.’

He does not recall conversations on the mechanics of the job and:

‘I was clearly drawing my own conclusions about what the objective of the job was.’

For example, he was not instructed what to put in reports but drew on previous Special Branch experience:

‘I knew how to put a report together. But exactly what was required, I think it was left to my own judgement, my own common sense.’

STOLEN IDENTITY AND A TRIP TO BLACKPOOL

James stole a deceased child’s identity to build his cover story. It was standard practice at that time, and he was given precise instructions on how to do it by senior management.

He never asked why it was considered necessary. He thought it might be to do with the Security Service (MI5) supplying cover documents for those undercover. It was good enough for him that other undercovers had done it before him, and that his bosses approved:

‘So I had no moral reservations about this at all… And I couldn’t see why it was a moral issue, because it didn’t involve anybody.’

Pressed on why he thought this:

‘No family were injured or caused any distress because of this practice.’

Later when queried by the Inquiry Chair, Sir John Mitting, he added:

‘I dismiss what I see in the press about what they say about the stress given to families whose children have been used in the way. I don’t accept that. From my own knowledge that didn’t happen.’

He visited Blackpool, the birthplace of the child he had chosen, to work on his cover story. To test the identity, he got assistance of local Special Branch and was assured that it would stand up to future attempts to investigate the cover background. The local colleagues also made discreet inquiries on his behalf into the whereabouts of the family and established they were no longer in the area.

PRETEND GIRLFRIEND

James prepared in advance a story of having a girlfriend, to have a reasonable excuse to rebuff advances. This was something he decided to do himself rather being suggested.

In the end, he rarely used the story. He did not divulge much about himself to targets and they were not very curious about him once accepted.

PRETEND HOME

James had several places to stay while undercover. The second one he had to move from as several activists lived nearby. He then looked around and found a suitable flat. As it was larger, he asked ‘Barry Tompkins’ (HN106, 1979-83), with whom he was already friendly, to move in with him. They both felt it would not be detrimental to their undercover work.

This novel idea was agreed to by management and was repeated in the later years of the SDS.

James was careful to prevent activists from visiting, and spent on average two nights a week there. It was not really a place to go and relax and unwind together.

The Inquiry was keen to know if living with Tompkins meant that they chatted. He was adamant that they rarely crossed paths and never discussed the relationships Tompkins had with women in his target groups.

This was somewhat in contradiction with his written statement, which says he had regularly discussed things with Tompkins. After going round the houses, he retreated to the line that the undercovers did not talk about their deployments with each other, adding that Tompkins never mentioned anything of significance in any case.

Evidence in the vintage documents released by the Inquiry suggests that Tompkins was thought to have a sexual relationship at the time. However, James insisted Tompkins:

‘was a professional officer who did his best to do the job he was being required to do – in the most professional way.’

Nevertheless, he is not surprised that Tompkins had such relationships.

REPORTING

James knew the SDS was set up to provide ‘background intelligence’ and information that assisted policing of large public order demonstrations. There was however:

‘no clear direction about what constitutes the information or intelligence that you might acquire.’

James relied on his own experience and assessment. In his witness statement he set out different ways in which information on individuals might be used. This included assisting Special Branch with the identification of people they would spot at an event or a demonstration:

‘Special Branch is an intelligence agency. It collated information about lots and lots and lots of organisations and individuals, much of which was filed and never used again.’

This was another strong theme of James’ throughout much of the rest of his evidence. Whether or not he was the source of intelligence in SDS reports, when pressed to justify various egregious bits of reporting, he fell back on the defence that it didn’t really matter. It was just information that mostly did not go anywhere. It was kept on the off-chance it might actually be useful one day, but since that was in the future, who knew, so you reported everything.

James is in no position to make that claim. Many of his reports were passed to the Security Service, and he can have no idea what was done with the information after that. All the files published by the Inquiry with a reference number beginning ‘UCPI000…’ are taken from the Security Service’s existing records.

James said his reporting was also used for vetting for government positions:

‘I was a Special Branch officer and that was the way that the system worked.’

As such, he asserted, the chances were that information retained on an individual might only have been:

‘looked at if that individual was applying for a post with some sort of security clearance’.

THE LIGHT OF DAY

The Inquiry showed February 1979 report [UCPI0000013171] profiling Socialist Workers Party (SWP) members, one of whom was a probation officer, and asked James what was the purpose of reporting their employment. James dodged straight to his ‘may never have seen the light of day’ argument.

Counsel to the Inquiry replied drily:

‘the fact that it wasn’t going to see the light of day again in your experience is not borne out by the fact that we’re looking at it now, is it?’

Pressed to explain, James brought out another of his evasive tropes:

‘I was just trying to paint a reasonable picture of these people. That what I perceived as being part of my job.’

Next up was report from June 1981 [UCPI0000015384], again detailing and SWP member, this time an inspector in the Department of Health and Social Security (DHSS). James admitted the report was solely for noting an SWP member was working there. As far as James was concerned, it was for others to decide what to do with that information:

‘I was an individual who had no control what then happened to that information, apart from my understanding that it was in the records that Special Branch retained.’

It was either used or it wasn’t. There was no clear guidance on what to report, he used his common sense, and no, nobody ever took issue with any of the contents of his intelligence reports.

Though not raised in evidence, it is believed the DHSS inspector is the subject of another report, where it is noted that they did lose their job. In the early 1970s, and again in the 1980s, such information was collected by a secret government committee ‘Subversion in Public Life’.

LEAVE THEM KIDS ALONE

A May 1979 report [UCPI0000021293] gives personal details abouta member of Clapton SWP & Hackney Women’s Voice. It describes how she is divorced with a six year old child, and is living with another SWP activist. Why report on the marital stage, the age of the child or even that she had a child?

‘All I can conclude is that I was trying to paint a picture of an individual that may have been used in the future.’

Would you have been concerned at all about reporting information on children?

‘Well, all I said was she had a daughter of six years. I mean, I’ve not gone into any more detail.’

For all he knew, she may well have been of interest to other parts of the police or Security Service – contradicting his claim that he knew what happened to information he reported. He added the chilling statement:

‘But I also knew that it would not be used in an aggressive or detrimental way if it was of no interest. It would just be filed.’

It was not James’ only instance of reporting on juveniles. In August 1979 he reported [UCPI0000013300] on an under 18 year old SWP member including the school they went to. He said he wasn’t concerned about this, chuckling as he said:

‘Under the age of 18, no. If it was under the age of sort of 12, yes.’

The Inquiry discussed other examples of intrusive reporting and asked him about justification. As far as James was concerned, you never knew when you might need it in the future.

TARGET: SWP

Like most of the undercovers heard from at these hearings, James’ first target was the Socialist Workers Party, with management tasking him to look at its organisation in East London.

He went in ‘cold’, with no briefing on the group or what management wanted him to look for in particular. James was fine with that, as he was an experienced Special Branch officer able to draw his own conclusions and make his own decisions.

Part of the justification for targeting the SWP was that their demonstrations were able to attract large numbers. Asked if the SWP presented a threat to public order, he responded:

‘They had the potential to cause problems to the police.’

He said this was borne out by his experiences undercover, where he saw ‘plenty of scuffles with the police and a few fights with members of the National Front.’

The Inquiry drew attention to a report into a planned Stop the Cuts demonstration in autumn 1979 [UCPI0000013343], at which several hundred people were anticipated, although it would be ‘relatively quiet and peaceful.’ However, he warned that SWP elements could attend. This James agreed was a good summary of his experiences of such protests:

‘The SWP, they weren’t an organisation that went out looking for trouble, but trouble often followed them.’

The Inquiry wanted to know if James could have identified this risk in advance through his infiltration of the SWP. Sometimes yes, he said, if he was in the ‘right place at the right time to get a better view of what would take place.’ He agreed the SWP often cooperated with the police in any case.

The Inquiry pressed on the point, if the main body of the SWP was not the problem, how did his reporting help uniformed police? James retreated to his stock answer, that the SDS were just a cog in a big machine.

There was brief mention of Red Action, a group that did confront fascists physically, and had been expelled from the SWP for this. James reported what he heard about them from other SWP members and was familiar with some of the people in the group. He had no response to the point that the SWP actively distanced themselves from Red Action.

TAKING RESPONSIBILITY WITHIN THE SWP

As with other undercovers we have heard from at the Inquiry hearings, James became active in a local branch, this time Clapton SWP, where he took on looking after paper sales and chaired meetings. In September 1979 he was elected to the Hackney District Committee. This was nine months into his deployment.

Asked why he accepted that role in the face of advice not to take up positions of influence in a group, he danced around the issue. He said he had reluctantly accepted, either because he didn’t feel he had much option to say no, or because it gave him better access.

James repeatedly tried to down play his role and influence in the local party organisation, saying that the decisions he was involved in were minor.

The Inquiry did not raise the point that, in such a role, James would have been seen as a significant local figure by other SWP members, whose voice would carry weight of its own. As as a member of the District Committee he would have been reporting back on national decisions and policy.

However, James’ main concern was that his target group would want to be in contact with him more.

A meeting of Clapton SWP, chaired by James himself, discussed the killing of Blair Peach by police at an anti-fascist protest, and that local SWP members were encouraged to attend a picket of Stoke Newington police station and a demonstration at Hammersmith Coroners Court.

Like so many of his contemporaries, James claims he recalled no discussion of Blair Peach among SDS officers.

The Inquiry drew James’ attention to several reports on the Friends of Blair Peach Campaign. Why was it necessary to include a list of those attending a picket the Stoke Newington police station where the Peach inquest was taking place? [UCPI0000013505].

James saw no reason why he would not have done so and fell back on them being probably SWP members, and the information might be important in the future.

‘It would have been remiss of me not to have identified them.’

A second picket took place in April 1980, a year after Peach was killed, and again James reported a list of those attending [UCPI0000013935]. The Inquiry picked up on the point that there had been no disturbances at these pickets, so there was no real public order issue. Yet again James said that:

‘These are people that… have taken part in this particular picket, they may be of interest in the future.’

In James’ view, the reporting was always about public order, never the individuals themselves, unless they were committing criminal activities. It was also about reporting on the SWP as a whole given what it was doing, and ‘the potential that it had to cause police problems’.

FAMILY JUSTICE CAMPAIGNS

Even if James was not the author of various SDS reports on family justice campaigns of grieving people seeking the truth about what happened to their loved ones, the Inquiry wanted to know whether there was a police purpose to some of the information provided in them.

The Inquiry brought up a July 1980 report on a proposed national coalition between family justice campaigns that Friends of Blair Peach was trying to bring together, with amongst others, the Richard ‘Cartoon’ Campbell Campaign and the Jimmy Kelly campaign [UCPI0000014149]. According to James, he was just being helpful to police trying to build up a picture.

The Inquiry notes that the Blair Peach Commemorative Demonstration of April 1981 is given its own Registry File within Special Branch [MPS-0730184]. James was unable to help with the codes for it.

Colin Roach was a young black man killed in Stoke Newington police station in 1983 and became a major cause celebre. In February 1983, James reported that an SWP member had been a steward at a Roach Family Support Committee demonstration [UCPI0000018700]. Asked to explain, he repeated that it could be of interest in the future either to police or security services.

TROOPS OUT MOVEMENT

At the end of 1980, James was tasked to move from SWP into Troops Out Movement (TOM) as there was no coverage of the group by the SDS at the time. He retained some social contacts with the SWP, frequenting the Hackney trades union bar.

James said that Special Branch was interested in TOM for public order reasons, but also:

‘Though there was an element of concern about whether it was providing support for the Irish Republican groups, who may commit acts of terror.’

Asked to be more precise, he said this was because:

‘Activists who openly supported a Republican organisation that included the IRA could be persuaded at some point to provide logistic support to an active service unit.’

The Inquiry returned to this later, pointing out that TOM’s aims were democratic in nature, but that in a final report on the group James said elements would continue to support unconditionally the armed struggle in Ireland, although he agreed that no practical assistance was given.

The SDS spied on groups who simply supported basic rights in northern Ireland (eg no internment without trial, inquiries into British forces killing unarmed civilians) in case they secretly supported Republican violence. They did not spy on any of the far-right groups who openly supported Loyalist violence.

In May 1981, James took part in a protest at the TUC headquarters over its lack of support around hunger strikers in Ireland, in order to report on it, [UCPI0000015367]. It was a peaceful occupation of a room, draping a banner out a window and addressing the public by megaphone. His senior officers were aware he was present.

TOM MEMBERSHIP & AFFILIATION SECRETARY

At the time, TOM was in a state of flux as a national organisation. The East London branch, based around Hackney which James was in, became a leading and active group. In particular, it set up a steering committee for TOM which effectively acted on a national level.

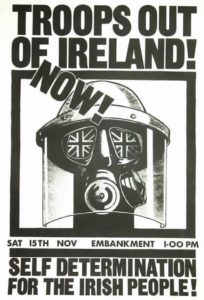

Troops Out of Ireland poster, 1975

James was appointed TOM’s Membership and Affiliation Secretary. As with the SWP, he repeatedly tried to downplay the importance of his roleto the Inquiry.

However, as with other undercovers, he had placed himself to be the first point of contact for new people and have access to names and addresses of members, as well as an idea of which groups were supporting TOM, points he did not address at the hearing.

He says he would have normally shied way from such a position, but accepted it as it would have given ‘closer insight into the things TOM were doing’. Later he claimed he took the job on ‘not really understanding what it entailed’.

James tried to deny he sat on any kind of central committee for TOM, a point that floundered badly when the Inquiry took him to a May 1982 report [UCPI0000018080] that showed that this was effectively what the Steering Committee was. James was so ‘inactive’ that he ended up chairing meetings of the Committee [UCPI0000018365].

He then tried to say he was not very active ‘in any proper sense’ and though he retained the title:

‘I did very little to further the membership of the Troops Out Movement.’

The Inquiry unfortunately failed to raise that inaction also has effects, and that by ‘doing very little’, he was undermining the group organisation. They did point out that while, due to the intensity of the work, most people stayed on the Steering Committee for only six months, James stayed in power for eighteen months, as a September 1982 report shows [UCPI0000015779].

The Inquiry then turned to a TOM demonstration of 8 May 1982. James was treasurer for the organising committee. People’s family members were coming from Northern Ireland. A meeting report [UCPI0000018026] noted that the group wanted to negotiate a route with the police. James confirmed that TOM ordinarily engaged with the police when it came to significant public events.

James said his purpose in being part of a committee negotiating with police was to establish good intelligence on demonstrations:

‘I was in the right place at the right time to feed into the police service the proposed demonstration of this particular organisation.’

It didn’t seem to matter that there was unlikely to be trouble, or that his action wasn’t being done lawfully.

The Inquiry has already heard how undercover officer Richard Clark (‘Rick Gibson’ HN297, 1974-76) set up a branch of TOM and climbed his way to the very top of the organisation before sabotaging it.

It has also heard officer Mike Scott describe how he assaulted TOM leader Géry Lawless for suspecting he was in fact a spycop and how, to this day, he doesn’t regard it as a crime because ‘it was acceptable to me’.

Self-justifying, abuse and crime comes naturally to the spycops. They give little reason beyond their self-defined remit. As Mike James so ably yet inadvertently explained, they are truly a law unto themselves.

Written witness statement of ‘Michael James’