UCPI – Weekly Report 14: 4-7 November 2024

Tranche 2, Phase 2, Week 3

4-7 November 2024

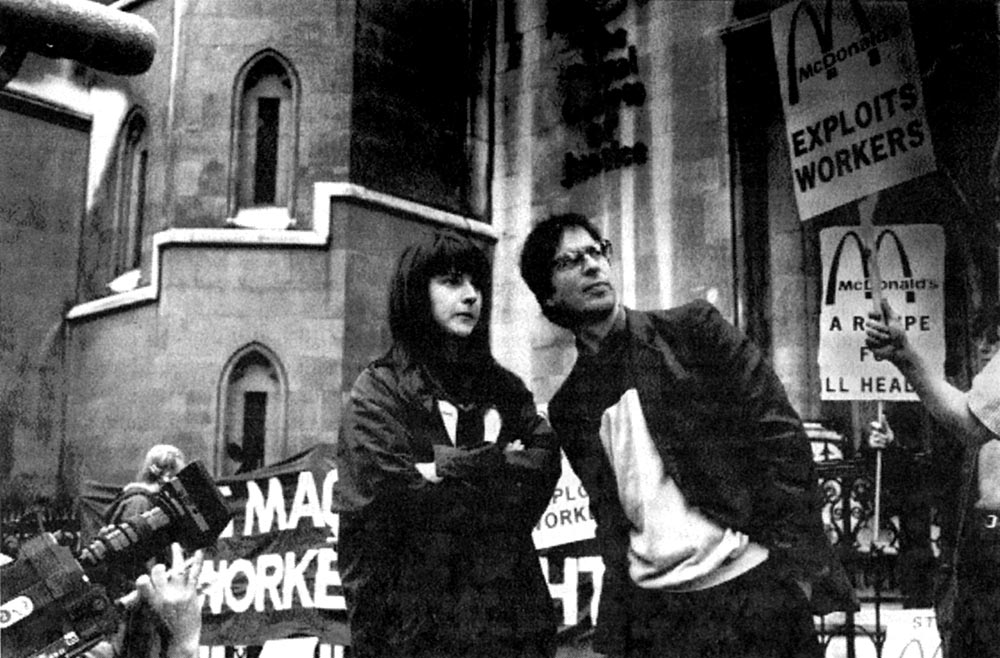

Dave Morris & Helen Steel of London Greenpeace outside McDonald’s (Pic: Spanner Films)

This summary covers the third week of ‘Tranche 2 Phase 2’, the new round of hearings of the Undercover Policing Inquiry (UCPI). This Phase mainly concentrates on examining the animal rights-focused activities of the Metropolitan Police’s secret political unit, the Special Demonstration Squad, from 1983-92.

The UCPI is an independent, judge-led inquiry into undercover policing in England and Wales. Its main focus is the activity of two units who deployed long-term undercover officers into a variety of political groups; the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS, 1968-2008) and the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU, 1999-2011). Spycops from these units lived as activists for years at a time, spying on more than 1,000 groups.

INTRODUCTION

The week was overshadowed by the Inquiry’s shock decision to suspend livestreaming. They say it is in order to prevent any unfounded allegations reaching the wider public.

However, the Inquiry has long used a ten minute delay on its livestreaming, and this has been sufficient to prevent any ‘blurts’ of secret information being broadcast. There is no reason why they couldn’t continue with that. Instead, they exclude the public from a public inquiry.

The Inquiry promised suitably edited transcripts of hearings by lunchtime the next day, and videos within five days. Despite very little of the testimony breaching the orders and needing any editing, they have not kept their word on either point.

All the testimony this week came from activists in London Greenpeace in the mid 1980s.

London Greenpeace was a small organisation, wholly separate from Greenpeace International. It was concerned with a wide range of environmental and social justice issues, opposing greedy exploitation of people, animals and resources.

An open public group with no formal membership, it held weekly meetings, usually attended by 5-25 people. It also held larger meetings with guest speakers, usually attended by 20-50 people.

It was infiltrated by Special Demonstration Squad officers including HN10 Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’ and HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’.

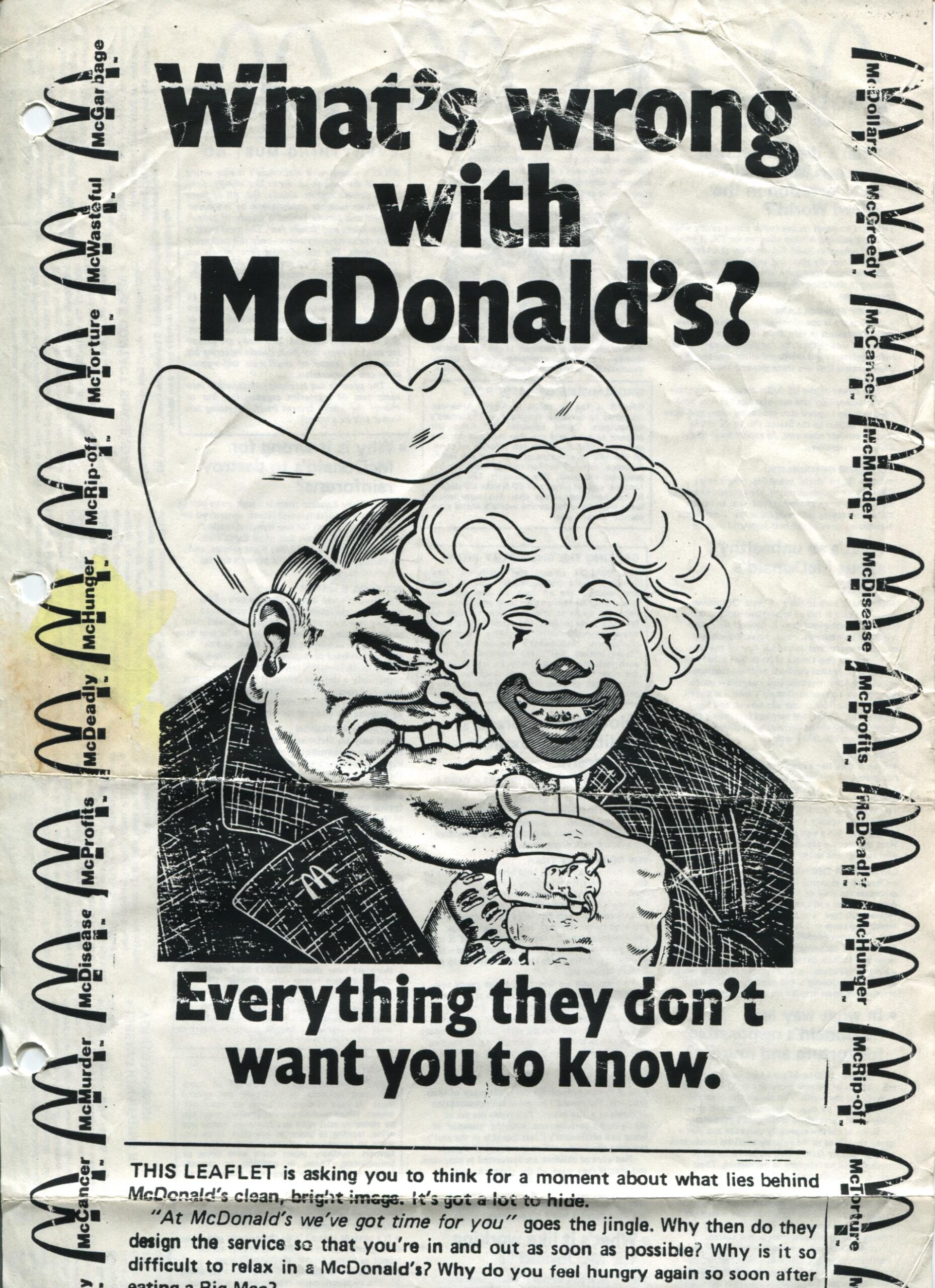

Lambert co-authored the group’s ‘What’s Wrong With McDonald’s?’ leaflet. The police gave briefings about the group to McDonald’s, and the corporation threatened to sue five named members of London Greenpeace for libel. Two members, Dave Morris and Helen Steel, fought the case. Known as McLibel, it became the longest trial in English history.

Despite the huge disparity in resources between the two sides – with McDonald’s spending huge sums on barristers while the defendants had to represent themselves – the court found that much of the leaflet’s assertions were true.

The fact of Lambert’s involvement, and of Dines having deceived Steel into an intimate relationship and so being party to her plans for the defence, were kept from the court.

The Undercover Policing Inquiry has found many of the officers’ secret police reports from the time. They are saturated with inaccuracies, exaggerations and outright false allegations about London Greenpeace and its members. The officers have made formal statements to the Inquiry and these too are full of such lies.

CONTENTS

Monday 4 November 2024

Evidence of Martyn Lowe

Click here for video, transcripts and written evidence

Martyn Lowe is a long-term anarcho-pacifist who has been involved in a number of groups over the years. Mr Hudson asked questions on behalf of the Inquiry.

Lowe has provided a written witness statement [UCPI036683], but this still has not been made available on the website.

The hearing began with him confirming his involvement in the Peace Pledge Union, part of War Resisters International (WRI), a pacifist organisation with sections across the world. They are recognised by the United Nations as an organisation which supports and promotes conscientious objection.

Asked to describe what he meant by ‘nonviolence’, he explained that this, for him, was:

‘a pacifist philosophy of not hurting or causing to be hurt or killed or damaged any individual’

He emphasised that he would not be willing to join any group that advocated violence.

The Inquiry is focussing on one of the many groups that Martyn has been part of during his life: London Greenpeace (LGP). This group was infiltrated by members of the Special Demonstration Squad, including HN10 Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’.

Protest against Torness nuclear power station. (Pic: Sottish Campaign to Resist the Atomic Menace/Friends of the Earth Scotland)

Lowe recalls getting involved around the time of a London to Paris anti-nuclear march, which took place in 1973, a couple of years after LGP was first founded. He remembers it having a democratic, non-hierarchical structure. The group had a series of shared aims and made decisions together at their weekly meetings.

The Inquiry was keen to learn if the entire group spoke with ‘one voice’ on any issues. Lowe remembers that many of the members at that time were opposed to nuclear testing in the South Pacific. They held demonstrations, for example a die-in outside the French Embassy. They distributed a broadsheet; originally this was published within Peace News.

He explains that the purpose of these demonstrations was to get their ideas across and persuade people that change was necessary. He says public disorder ‘was never on the agenda’ and can’t recall any occurring at LGP demos. In his witness statement, Lowe had mentioned a campaign against the construction of a new nuclear reactor at Torness in Scotland, and the Torness Anti-Nuclear Alliance which formed.

He remembers that the different groups involved in it had an agreement not to sabotage or destroy property on the site during the mass protests there, and different forms of direct action were debated.

He points out that ‘some property should never be produced in the first place, so destroying it I’ve got no problem with’.

He doesn’t consider property damage a ‘violent act’, especially when the aim is to immobilise an item and prevent it being used to cause harm.

War Resisters’ International logo

The War Resisters International logo features a broken rifle, an apt symbol of their beliefs, but actually breaking a weapon is not as ‘straightforward’ as the image suggests, and he says this kind of action shouldn’t be romanticised. It is not something he’s ever done himself.

We were shown a description of the work of LGP, written for a WRI conference. Lowe recognised this. Asked who had written this text, he explained that a number of different versions were produced over the years, and various people would have been involved in what was a collaborative process. One person might produce a draft and others would contribute ideas and comments. Such texts would be discussed at the group’s meeting and they generally reached agreement about the content of leaflets before printing them.

SPYCOP LAMBERT

Lowe first met HN10 Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’ at one of the group’s meetings, and remembers that ‘he just turned up’. He still remembers him as ‘highly intelligent and very amiable’.

We know that Lambert’s deployment began in June 1984. How was Lowe’s relationship with him over those first 6 months? ‘Very friendly’. They tended to go to the pub and drink together on Thursday evenings, after the group’s weekly meetings.

The Inquiry wanted to know more about Lambert’s influence on LGP, and the roles he took on within the group, and how his age compared with other activists.

Lowe recollected that Lambert kept trying to persuade him to get involved in hunt sabotage. He would bring up issues in the group, but didn’t take on any ‘formal tasks’ (such as dealing with finances). They were around the same age as each other (35) and at the time the majority of the group were probably in their late 20s/ early 30s.

He was next asked about the direction taken by LGP over the years. Lowe left LGP in around September 1985, after being involved for over a decade. He recollected an incident which made him notice that the group had ‘really changed’. This was the derailment of a train carrying a nuclear flask in Stratford, East London.

When he first joined LGP, it had been very much an anti-nuclear group, but he encountered ‘disinterest’ in the group when this happened.

ANIMAL RIGHTS

Almost all of the rest of the questioning of Lowe was about Lambert, animal rights and the Animal Liberation Front (ALF) and non-violence.

Lowe realised that many of the newer people, who he thinks were influenced by Lambert, were more interested in the issue of animal rights:

‘that’s the point at which I really started thinking: why am I here?’

LGP had been interested in a very wide range of issues before then, and although many activists were vegan or vegetarian, the group didn’t focus its attention on animal rights. It had a more holistic understanding of the way that issues were interconnected, e.g. war is not good for the environment, and harms animals just like it harms humans.

Ronnie Lee was a founder of the Animal Liberation Front in the mid-1970s. He was imprisoned in the 1980s for his part in animal rights actions. Lowe remembers coming across him in the peace movement, and then briefly seeing him at LGP meetings in around 1974.

Ronnie Lee (left) with friend

Over the years Lee would occasionally drop in at meetings or demos, as did other people, but never got involved in running the group.

Lowe recalls being ‘somewhat taken aback’ to hear about Lee’s arrest; his main memory is of Lee’s work with an organisation called Vegfam (a charity set up by Christians in 1963 to distribute plant-based food and fruit trees to people in need around the world).

According to Lowe’s witness statement, the issue of animal liberation wasn’t usually brought up at LGP’s meetings, at least not until Lambert showed up.

The Inquiry then displayed some leaflets produced by LGP. One of these leaflets, dated April 1980, sought to address the confusion about the relationship between ‘London Greenpeace’ and the newly-established ‘Greenpeace UK Ltd’. It explained the philosophical, organisational and political differences.

The Inquiry asked if this leaflet was aimed at people involved in animal rights. Lowe explained that at that time, the philosophy behind animal rights and liberation was still developing, but many pacifists were also vegetarians – the two went ‘hand in hand’.

The LGP leafelt said that ’The one group which which we can express political agreement is the Animal Liberation Front’. It described Ronnie Lee as ‘an ex-group activist’.

Lowe explained that the ALF always checked to ensure that nobody was hurt in their actions, and were non-violent.

Did this leaflet not show that LGP was closely aligned with the ALF as early as 1980, before Lambert arrived? Lowe says no, this was just one of many briefings produced in this era to share information about the range of campaigning groups which existed. There was no ‘working relationship’ between the two groups.

An intelligence report [UCPI020790] submitted by HN11 Mike Chitty ‘Mike Blake’ (deployed to spy on animal rights campaigners in South London) in April 1984 tells of a ‘dramatic increase’ in animal rights activity, increased public concern and support for the movement.

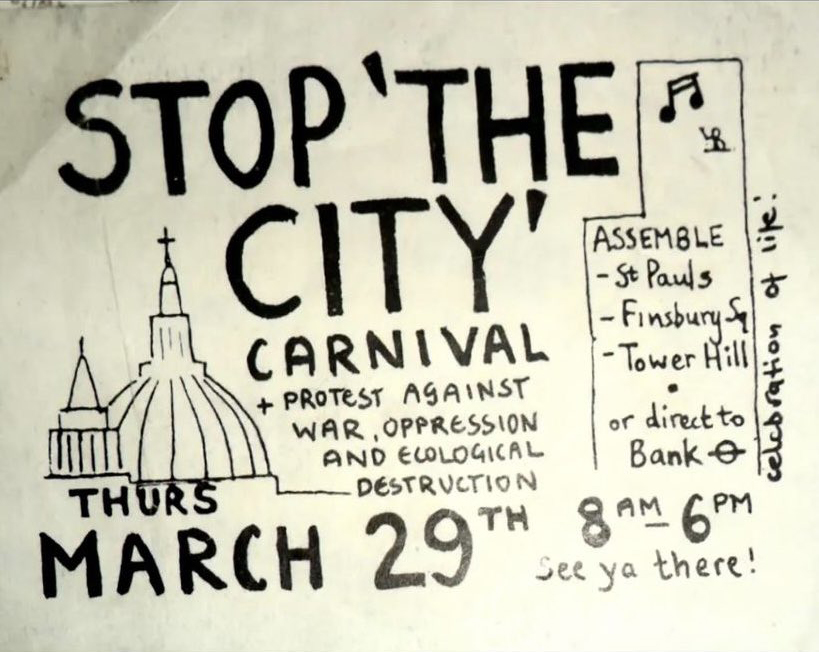

Lowe says he wasn’t especially aware of the issue at the time, so can’t comment on the accuracy of this report. This wasn’t an issue that LGP was concerned with – they were busy in the early 1980s producing a range of educational factsheets, campaigning against the Falklands War, and protests against financial institutions including supporting the ‘Stop The City’ series of protests.

The same report suggests an upsurge in direct action:

‘in the main confined to younger anarchist members of the movement, most of whom will be unemployed and prepared to spend some time in police cells.’

Was LGP’s new interest in animal rights driven by the younger people joining at this time? Lowe believes it was in fact driven by Lambert going out and recruiting people who were interested in animal rights to come along to LGP.

In his statement Lowe recalls being suspicious about Lambert’s involvement in opposing the deer cull which took place in Richmond Park over several summers in the 1980s. He clearly remembers sitting in a meeting, listening to Lambert talking about locking the gates of the park, and thinking ‘he knows more about this than he’s saying’ to the group.

LAMBERT FRAMING OTHERS

We moved on, and saw a handwritten notice about a demo which took place outside the AGM of dairy company Unigate, held at the Dorchester Hotel in September 1984. Lowe is absolutely certain that this is Lambert’s handwriting, and so is the leaflet handed out on the day, titled ‘Unigate Murders Animals’.

However a police intelligence report [UCPI020434] submitted by Lambert dated 31 August 1984 says Martyn Lowe was organising ‘support and publicity’ for this demo. Lowe denies doing anything of the sort; he remembers this as a demo organised by Lambert himself.

Another SDS report [UCPI020189], produced after the demo, lists the names of those who attended, and calls Martyn Lowe the ‘organiser of the picket’. All he did was turn up. A picture exists of ‘Bob’ at the demo.

In another report [UCPI020220], Lowe is describing as organising another demo that same month, this one a picket to protest fur fashion shows held at Claridge’s Hotel. He is adamant that this is not true, and he didn’t even attend that picket, as he was at work until late that day.

His name crops up in relation to a similar Claridge’s demo in one more report [UCPI020230] and again he denies being involved in any conversations about the planning for this protest, and wonders if names like him were just added later by SDS back-room staff.

This was a point that recurred in the other testimony later in the week – Lambert organising animal rights activities but then writing reports attributing them to others.

According to the report of an LGP meeting, Lowe had also expressed concerns about Stop the City being a ‘potentially violent’ demonstration. He denied this. He didn’t have a problem with Stop the City, and saw it as a way of bringing anti-militarist action out of rural areas and into the city where the arms companies were based.

McDONALD’S

How did LGP come to highlight McDonald’s?

Lowe remembers Lambert making a comment in the pub one night, suggesting that it was time to target fast food companies. As a result, he was inspired to draft a spoof leaflet when he got home, referring to McDonald’s as ‘the sawdust people’. This became the basis for a flyer advertising a day of protest vs McDonald’s in January 1985.

It mentions ecological concerns as well as the treatment of animals. Lowe recalls contributing the lines about sawdust, but can’t be sure who added which other bits.

That demo went ahead on 19 January 1985 and Lowe did not attend it. He says he wasn’t involved in organising it either, but an SDS report [UCPI014460] says that he, Dave Morris and Albert Beale were all involved in this.

After Martyn left the group, ‘Bob’ continued to correspond with him, sending him gossipy letters. Some of these have been provided to the Inquiry as exhibits.

One from April 1986 was shown, it contains lots of encouragement to come back to a LGP meeting sometime, or at least join the group in the pub one night. It also asked about getting hold of a book (‘Big Mac: the Unauthorized Story of McDonald’s’). Lowe worked as a librarian at the time. This showed Lambert’s involvement right at the start of the creation of the ‘Whats Wrong With McDonald’s?’ Factsheet, which later led to the McDonald’s libel action.

Lowe did not see Lambert again in person until LGP members exposed him in October 2011.

WITHDRAWING SUPPORT

After a short break, we returned to hear about a LGP meeting that had taken place in January 1985.

According to the SDS report of it [UCPI014474], Lowe proposed that the group, as an anarcho-pacifist one, ‘withdraw its support for the Animal Liberation Front‘ (ALF), following a number of actions which he did not agree with.

He couldn’t remember the exact words he’d used at the time but clearly still felt the same way about those actions, referring to one as ‘stupid’.

The Inquiry was very keen to explore this issue further, and asked if this implied that LGP had therefore supported the ALF up till this time.

Lowe drew a distinction between the non-violent position of the ALF and the more violent tactics of the Animal Rights Militia (which no-one seemed to know anything about). He went on to claim that the ALF had put out ‘a leaflet or a document’ around this time which he took to mean they now supported the use of some violence.

He knew that many LGP activists were sympathetic towards the ams of the ALF, but had no idea if anyone was actually involved in taking that sort of action.

He went on to say that after attending LGP meetings week after week for so long, he had grown ‘tired of it’. There wasn’t anything specifically objectionable about the group; it was the ‘general attitude’ that he struggled with. He saw punk as a trend and for some people a ‘style statement’.

According to the report, ‘Lowe’s comments were met with derision’. Lowe doesn’t remember derision, or exactly what people said, but remembers that they disagreed with him. He doesn’t recall if Dave Morris argued for the group to continue to support the ALF.

LOWE LEAVING

It is reported [UCPI028493] a full year later that Martyn Lowe has now left the group, in December 1985, following ‘many arguments’ with Dave Morris and others. Lowe is clear that he and Morris often disagreed and argued about politics, but he still liked the man. They just had different approaches. He knows that Morris ‘has always been more in favour of doing direct action’.

Even though the type of action used as an example in this report (some butchers’ windows being broken by ALF activists) might be described as ‘non violent direct action’, it is obvious that this is not a form of action Lowe would choose to take himself. He does not consider it ‘wise’ and is very conscientious, pointing out that someone might have cut themselves on the broken glass.

In his statement to the Inquiry [UCPI035081], Lambert says that the reason he was reporting on Martyn Lowe (someone who had been of interest to Special Branch since at least as far back as 1978) was his involvement in LGP, and that his departure from the group was worth reporting too:

‘if Lowe ceased to be involved in supporting violence, future reporting might not be necessary’

Martyn Lowe is adamant that he has never supported violence:

‘I have been a pacifist all my life’.

Lowe was asked for his views on Class War at this time. They ‘had no qualms about using violence’ says Lowe. He felt they were overly confrontational and ‘gave anarchists a bad name’. He never had these concerns about LGP.

We saw one more letter, sent to Lowe in January 1986. It was read out in full, for some reason. In it Lambert mentions Dave Morris, and says he is now in Amsterdam, having been fined £100 in court for shoplifting ‘booze’ (despite being teetotal). [See below for Dave Morris’s testimony the following day, which tells the interesting story about this.]

Asked by the Inquiry to comment on both of these men, Lowe agrees that Morris was a ‘dominant figure’ in the group, with a ‘strong personality’.

He says that in retrospect he’s seen how Lambert exerted influence in a different way, ‘by being the nice guy, the friendly bloke’ who targeted individuals one by one, adding that ‘I just regret that I didn’t pick up on this at the time’.

LAMBERT’S RELATIONSHIPS

Lambert had a number of sexual relationships while he was undercover. The first was with a woman known in this Inquiry as ‘CTS’. She came along to LGP meetings, and Lowe recalls her turning up for the first time about 6 weeks after ‘Bob’.

Spycop Bob Lambert whilst undercover

He says she was ‘very pleasant, and concerned about, you know, changing the world for the better’, and ‘about 19’ at the time. Lambert was a married man in his 30s.

It soon became obvious that she and ‘Bob’ had become a ‘devoted couple’ sometime that summer, but Martyn can’t be sure of the exact date. We can see from Lambert’s report that she was present at the Unigate demo.

They both came over for dinner, he recalls. Again, he can’t give an exact date, and only has his impressions, of them being ‘devoted to each other’. He saw them together at meetings but doesn’t know how much time they spent together.

Lowe is shown a photograph that he took of the couple at his home. There is a second photograph, taken on the same occasion. Asked what these two images tell us about the nature of their relationship, Lowe gave the same answer both times: they were ‘very close’, and ‘devoted’.

‘CTS’ went off to university in October 1984, and came back to London that Christmas. She and Lowe met up, and he had the impression she was planning to see ‘Bob’.

Lowe is not sure when they broke up, or when he learnt of this. It’s not clear exactly how long the relationship lasted but it seems to have been over by the end of 1984. Almost two years later, in September 1986, Lambert mentioned this young woman in another of his letters, saying ‘let me know instantly’ if you see her.

Next, Lowe was shown Lambert’s own witness statement. His version of events is that he formed ‘a friendship’ with ‘CTS’ during the group’s trips to the pub in around July 1984. He claims this became a ‘short sexual relationship’, lasting just one month, before she left town in late September. He says she came back to visit once, ‘probably early October’ , he can’t remember what they did then but hasn’t seen her since.

Why does Lowe believe Lambert ‘ditched’ her? (the word he used in his statement). Lowe explains that he had got this impression, along with the idea that the ditching took place in December, but doesn’t know for sure who ended the relationship. However he believes that Lambert treated ‘CTS’ ‘really badly’. And is still ‘really upset that anyone could behave that way’.

He recalled that after the relationship ended, ‘CTS’ no longer wanted anything to do with the LGP group.

‘She got badly hurt, that’s the only way I can describe it’

Lowe didn’t see her again for a long time. He tried to track her but wasn’t able to find her.

It was only after she saw a story in the Guardian in 2011 that she got in touch with Martyn, via journalist Rob Evans.

How does he feel now about Lambert’s infiltration of the group?

‘I’m not angry, I’m just disappointed that we’ve had to go through this whole process’

YouTube video of Martyn Lowe’s hearing

Tuesday 5 and Thursday 7 November 2024

Evidence of Dave Morris

Click here for video, transcripts and written evidence of Tuesday 5 November

Click here for video, transcripts and written evidence of Thursday 7 November

Dave Morris

Tuesday morning was due to start with Dave Morris’s evidence, but was instead taken up with an emergency hearing where the Inquiry heard legal objections to the Inquiry Chair’s sudden shock decision to not allow livestreaming of hearings for the next four weeks. A bizarre turn of events for a Public Inquiry.

The Inquiry has, up to now, been livestreaming with a 10 minute delay in case a witness mentions something that shouldn’t be said. This has been deemed necessary to protect police secrets and national security. It has been very successful in that, yet this same method is apparently not enough to prevent personal details leaking out about a few named people. That is, obviously, bollocks.

The Inquiry Chair rejected a proposed range of practical options put forward by Core Participants (CPs) and their lawyers for protecting privacy during livestreaming.

The Chair stuck by his controversial decision, but conceded that CPs, their lawyers and accredited media – but not the wider public – would be able to access a livestream through a special Zoom link. They would need to agree to be bound by any Restriction Orders. This would only start on Thursday.

DAVE MORRIS OVERVIEW

The afternoon session was Dave Morris’s second appearance giving evidence as a witness at the Inquiry. Morris had previously given evidence on 8 July 2024, regarding activities of groups spied upon during the mid-1970s to the early 1980s – eg London Workers Group, Anarchy magazine, Person Unknown defence campaign, Torness anti-nuclear protests, and ‘Stop The City’ events.

In this phase of the Inquiry he was giving evidence about London Greenpeace, the McLibel case, and the Poll Tax/ Trafalgar Square Defendants Campaign.

He had given an Opening Statement to this phase of the Inquiry in October:

ORGANISING IN HIS LOCAL COMMUNITY

Tuesday’s session began by Morris verifying his Witness Statement and Section D of his written Opening Statement. Elements of those have been incorporated in this report.

The Counsel to the Inquiry, Emma Gargitter, posed the questions, initially exploring Morris’s local activism in the North London borough of Haringey in the 1980s. His main activism throughout the decade was with Tottenham Claimants Union (TCU).

Dozens of local Claimants’ Unions had existed throughout the country since the early 1970s, linked through a Federation and regular national conferences. They were made up of people on benefits (pensioners, unemployed, people with disabilities, single parents, etc), supporting each other, promoting solidarity and campaigning for people’s needs.

For example, a May 1988 secret police report detailed a planned protest by the Tottenham Claimants Union protesting against a National Front activist being employed at a local Social Security office. The TCU was based in an Unemployed Centre and then set up their own Haringey Unwaged Centre (which later hosted the local anti-poll tax campaign, featured below at the end of his testimony).

A MAN OF CONVICTION

Note: At the end of his evidence, Morris took the opportunity to respond to a letter that spycop HN10 Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’ had sent to Martyn Lowe in 1987 which had been read out during the questioning of Lowe. It had included reference to Morris being fined for shoplifting.

The grave of Mark Robert Robinson whose identity was stolen by spycop Bob Lambert

Morris felt he should therefore explain the full story. A member of the Claimants Union with learning difficulties had been able to get a specially protected job at a local Tesco’s.

However, in the run up to Christmas he was sacked ‘due to not working fast enough’. This outraged union members, who launched weekly ‘Reinstate Steve Now’ protests at the supermarket, including members secreting leaflets on the shelves throughout the store.

Just before Christmas, Morris was helping organise a Claimants’ Union Christmas party, and went to buy provisions at the store. He knew Steve would be attending and decided to get him a bottle of cognac as a present. Morris himself is a non-drinker. Due to what had happened to Steve he thought it only fair not to pay for that and hid it in his jacket.

However, a store detective had recognised him from the previous CU protests and was following him around the store in case he was distributing leaflets. Arrest and fine unfortunately followed! In the end the ‘Reinstate Steve’ campaign was unsuccessful.

Morris was also involved in Haringey Community Action, an open collective supporting a wide range of local campaigning. The Inquiry examined a police report about a bulletin HCA supported called ‘Haringey Anarchist News’.

LONDON GREENPEACE

Organising in his local community had been, and continues to be, the primary focus of Morris’s activism, although occasionally getting ‘side-tracked’ for example by the long McLibel court case and campaign in the 1990s. That case came out of his other key focus in the 1980s, London Greenpeace (LGP).

An early police report, using terminology with the disdain typical of the spycops, (mis)characterised Morris’s ‘naivety and childish enthusiasm’ that supposedly allowed him to be accepted by younger activists despite being an ‘old hippy’. Morris simply shrugged this off, noting that he had been 36 and ‘everyone is entitled to their point of view’.

LGP was Europe’s first Greenpeace group which had formed in the early 1970s. It decided to remain independent when Greenpeace International set up a UK branch in 1977.

Morris joined in 1982 during opposition to the Falklands War, as it was one of the few groups in London explicitly opposing both sides in the war – the UK and Argentina. He already knew some members from his campaigning against nuclear power in the late 1970s.

When questioned about the group’s politics and ‘loose’ organisation, Morris emphasised that, despite the lack of formal structure, they were very focused and effective. The group met weekly with an open agenda and replied conscientiously to more than 50 letters from the public every week.

He detailed how LGP produced numerous leaflets and factsheets on various topics, and included them in regular mailouts. The group’s politics centred on anti-militarism and anti-nuclear campaigns up to the early 1980s, and then with an additional focus on environmental issues, anti-capitalism and class struggle in the mid-1980s.

They were always keen to also promote examples of alternative ways people could use to run society themselves – although anarchist ideas were more implicit than explicit. Animal rights campaigns, which had not featured at all in the group in the 1970s, began to feature in the mid-late 1980s.

He explained their open meeting structure, noting that there was nothing to stop a spycop secretly attending and then disappearing – no-one would have noticed. The agenda was formulated by passing around a piece of paper anyone could write on.

INFILTRATION BEGINS

Undercover police officer HN10 Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’ infiltrated the group and was felt to be highly influential, using full access to set agenda items, suggest topics for discussion at public meetings, help to write leaflets and organise activities, and network with others outside the group.

Spycop Bob Lambert whilst undercover

Morris noted that Lambert was particularly keen on the regular post-meeting gatherings in the pub (which included people not attending the meetings), though Morris himself didn’t drink and was too busy to attend those.

There was also an office that people in the group used for answering letters and ad hoc meet ups, though Morris rarely visited. Looking back now, Morris concluded that Lambert was manipulating and exploiting for his own ends those who trusted him, both within and outside the group.

When asked about LGP breaking the law, Morris’s witness statement indicated the group generally organised peaceful traditional protests including pickets, leafleting, posters, stickers, sit ins, etc.

Morris was questioned about the role of treasurer, particularly as spycop HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’ had held this position of trust and therefore had access to private information on those making donations.

A secret police report of Lambert’s from January 1985 suggested three ‘leading’ figures in LGP: Martyn Lowe and Albert Beale (both involved since the early years of the group), and Morris.

While Morris acknowledged his influence due to his strong personality and commitment, he emphasised that none of them held any real power, explaining that very many people in the group contributed in different ways and all were equally important.

He described how he brought his priorities of community organising and class struggle to the group while respecting its established nature. In particular, he encouraged the group to reach out to new people as much as possible. This included encouraging the environmental and peace movements to support mining communities during the historic 1984-5 miners’ strike.

Morris noted one ‘very worrying’ report by Lambert, sent to MI5, that had detailed information on his planned visit to Poland to meet anti-government activists there. Morris explained that, bearing in mind the savage repression at the time in Poland, this could have put people there (including some mineworkers he met with who were hoping to link up with miners in Britain) at serious risk.

EXAGGERATION AND FABRICATION

Stop The City sticker, 1984

A report by Lambert dated 30 January 1985 (mis)described Morris as ‘a supporter of any action that could be described as anti-establishment’. Morris flatly rejected this, as he judged each activity on its merits.

He emphasised that the fight for a better world wasn’t just about being ‘anti’, but also about finding positive and better alternative ways of doing things, and showing by example.

In the mid-late 1980s numbers attending LGP meetings rose significantly. This, Morris felt, was due to the inclusive and welcoming nature of the group, the many public meetings, and the wide range of issues discussed and campaigns supported.

In a recent interview by the police investigating Lambert’s controversial deployment, Lambert had portrayed Morris as a veteran of LGP and the London anarchist scene, claiming he had a ‘violent anarchist vision’, an assessment Morris disputed.

We’d already heard in Martyn Lowe’s testimony how Lambert exaggerated and invented his descriptions of activists, and it was something we’d hear again too.

Lambert’s reports sometimes alleged the Stop The City protests of 1983 and 1984 to be ‘violent’.

Morris rejected this, explaining they were billed as a ‘carnival against war, oppression and destruction’ and a ‘celebration of life’, and were largely a range of decentralised educational and festive activities and protests to challenge and reclaim the financial district of London.

Despite their almost entirely peaceful nature, the police had seen fit to arrest hundreds of participants in order to try to protect ‘business as usual’.

Lambert’s reports tried to portray Morris and Lowe as at loggerheads, yet Morris noted they agreed on 95% of political issues, and respectfully disagreed on a few points.

Morris criticised the spycops for having what he called a ‘childish view’ of how people operated and how relationships developed, often inventing or stirring up serious personality clashes and power struggles.

The spies fantasies of supposed command structures, and their competition to impress their managers, says more about the officers and the police than it does about the group they’re reporting on.

OPPOSING CRUELTY TO ANIMALS

The Inquiry then spent an hour or more exploring in minute detail London Greenpeace’s connections to the animal rights movement and their campaigning against animal cruelty.

Morris had never been involved in that movement but was somehow expected to answer a raft of questions about it. He noted he’d been vegetarian for nearly 50 years, and only managed to be vegan for a few years in the 1980s ‘out of weakness’.

The Inquiry, just like the establishment and media hysteria at the time, apparently regards the animal rights movement as potentially ‘violent’ or even ‘terrorist’ irrespective of what they actually stood for and actually did.

Morris had at one point attended two hunt sabotage events (shock, horror!) to see what they were all about. One such event involved Bob Lambert’s arrest and release without charge, though Morris couldn’t recall the specific incident.

Morris praised the efforts of thousands of activists going out into the countryside every weekend to try to save the lives of individual foxes being terrorised and killed for supposed sport. He pointed out that these selfless efforts over decades eventually led to such hunting being made illegal.

Animal rights had gradually become one of the key issues in LGP between 1985 and 1988, Morris confirmed. He felt that after the inspiring the Stop The City protests in 1983-4 many new people, especially younger people, became interested in the group’s open and accessible meetings and its radical and non-sectarian ideas.

At one time about 20 people were attending the regular weekly meetings, and 40 or more at public meetings with guest speakers that were monthly.

Lambert – who, like all Special Demonstration Squad infiltrators, was obsessed with identifying sinister ‘leaders’ – implied in a report this influx was down to Morris’s personal ‘vision’.

Crass at the Cleatormoor Civic Hall, 3 May 1984. (Pic: Trunt)

However, Morris described how many young people at the time, particularly in the ‘punk’ movement, were attracted to DIY politics, veganism, anarchism and pacifism – especially through the widespread influence of the anarchist band Crass. And it was clear that Lambert himself was strongly influencing things.

During this period, LGP was invited to do stalls at punk gigs, reaching a new audience.

Morris now believes LGP served as a platform and ‘a sea to swim in’ for Lambert, who showed particular interest in new attendees.

The Inquiry examined a 1980 leaflet titled ‘Greenpeace, Animal Liberation and the Rest’. At the hearing the day before, Martyn Lowe had explained that he had drafted it in response to Greenpeace International’s recent arrival in the UK, to try to clarify some of the confusion this had created.

The leaflet detailed the distinction between the need for rights for all animals and for veganism, in contrast to Greenpeace UK’s focus on conservation, eg regarding whales.

Morris explained that LGP had for many years supported and sent donations to the Sea Shepherd anti-whaling ship which had split from Greenpeace International over this issue. He also noted that Ronnie Lee, who later helped found the Animal Liberation Front, had briefly attended London Greenpeace meetings in 1974 but didn’t stay involved.

The intense and narrow questioning continued. Morris emphasised that LGP was never directly involved in Animal Liberation Front (ALF) direct action activities, though a few individual members may have been. He highlighted the ALF’s non-violence policy, and that none of its actions were to cause any harm to people or animals.

He described Bob Lambert’s significant influence in LGP, noting his focus on animal rights and his pushing for activists to engage in animal rights activities and direct action.

In reality, the group’s support for the ALF was mainly through including ALF Supporters Group leaflets in their regular paper mailouts, which contained a wide range of political educational literature.

A police report of Lambert’s from January 1985 mentioned some concerns raised at a meeting about the ALF’s direction and the group’s continuing support. Martyn Lowe was said to be leaving LGP after 12 years following ‘many arguments with Dave Morris and other group members’ – Lambert again personalising things inaccurately.

Morris explained there was a duplicator printer in his house that he shared with others, which he taught and encouraged others to use. He said a wide range of materials of all kinds would have been printed there, but he couldn’t recall any printing of specific ALF documents.

Morris repeatedly emphasised that while his lack of involvement in the animal rights movement wasn’t a criticism of it, he simply wasn’t involved, just as he wasn’t involved in the anti-apartheid movement, and so on. He did say that, in that house, someone looked after some rescued laboratory rats for a short while.

Morris estimated that by this point, animal rights issues occupied on average about 10-30% of the time during the group’s meetings. He dismissed outright Lambert’s claims that a majority of LGP members were ‘long-standing ALF activists’, calling it ‘total rubbish’.

In contrast with Lambert’s reports and the Inquiry’s line of questioning, in 2011 Lambert himself described LGP as ‘a peaceful campaigning group’ and apologised to members for his deception.

Morris described how Lambert, as an influential character, was seemingly exploiting and manipulating LGP, its meetings, its office, and related gatherings in pubs for his own agenda. He wanted to promote militant direct action and act as an agent provocateur.

DEBENHAM’S

Firefighter in the wreckage of Debenham’s Luton store after 1987 timed incendiary device

The Inquiry examined a July 1987 Lambert report about a regular weekly LGP meeting. It followed media news of timed incendiary devices being planted at three Debenham’s shops to trigger sprinkler systems in their fur departments in protest at the chain selling fur.

The report claimed an older pacifist was critical while everyone else supported the ‘arson attacks’.

Morris, in the witness box and in his written statement, disputed that these were ‘arson’ attacks, and felt that most ‘support’ was likely to be for the aims not the tactics employed.

In fact, we now know that there’s a huge amount of evidence that Lambert himself was involved, even the driving force, behind the Debenham’s action.

Throughout the testimony, Morris had emphasised that LGP maintained a broad and inclusive range of concerns and activities despite the spies’ attempts to portray it otherwise.

YET MORE ON ANIMAL RIGHTS

The questioning during the first part of Dave Morris’s second session, two days later, continued to focus on animal rights campaigning.

There seemed to be an unspoken assumption from the Inquiry’s legal team that such campaigning was itself somehow potentially incriminating.

Morris said that he’d always been supportive of animals having rights, and that they shouldn’t be exploited and killed, but he affirmed yet again that he had never been personally active in the movement.

A police report from January 1988 described Morris preparing a draft LGP statement supporting Geoff Sheppard and Andrew Clarke who were by that time on remand for the incendiary device damage to Debenham’s shops.

Sheppard and Clarke were involved in various animal rights groups and had attended some of the LGP meetings.

Morris explained that movements should always support arrested activists going through the judicial process, but it didn’t necessarily mean support for any specific acts alleged or whether defendants were even going to plead guilty.

And, he pointed out, no serious defence campaign could condemn any alleged action of a defendant. Morris said he made a visit to Clarke in prison to offer moral support.

In March 1988, police reported on a LGP public meeting of 43 people with guest speaker Robin Lane, former press officer of the ALF Supporters’ Group. The report claimed that the Debenham’s incendiary campaign was praised.

Morris couldn’t recall the exact meeting but confirmed some speakers occasionally attended LGP meetings to speak in support of the aims of the ALF (and indeed many other issues). He added that he was not in principle opposed to nonviolent direct action that damages property, but it had to be looked at on a case by case basis and at no risk to the public.

In his witness statement he noted how there were now statues of Nelson Mandela, Mahatma Gandhi and the Pankhurst sisters in Westminster unveiled with great acclamation from the government and public, yet their direct action movements (against apartheid, for Indian independence, and for women’s right to vote) had been panned as ‘terrorist’ at the time they were involved.

A police report also claimed that the ALF Supporters Group shared an office with London Greenpeace. Morris wasn’t aware of this at all, and doesn’t remember them having any meetings in the office, though they may have used the address for a time for receiving mail.

Morris was consistent and clear; LGP was entirely open and transparent. Animal rights campaigning by the group was perfectly legitimate and only ever a minority theme of the group’s activities.

McLIBEL

The questioning at last moved on to other matters that Morris had actually been significantly involved in, including the two issues he could most help the Inquiry about – firstly, the anti-McDonald’s campaign, and then the Poll Tax movement (about which Morris is the only witness to testify in the Inquiry).

The McLibel 2, Helen Steel and Dave Morris, at the Royal Courts of Justice (Pic: Nick Cobbing)

In the mid-late 1980s London Greenpeace organised a number of anti-McDonald’s events, which largely amounted to talking to the public and handing out leaflets in the street outside a branch of McDonald’s. They focused on McDonald’s as a prime example of what was wrong with the consumer-capitalist worldview. It went down very well with the public.

McDonald’s had been separately criticised by trade unions over workers’ rights, by ecologists for environmental damage, by nutritionists for health impacts, by child welfare campaigners for their advertising targeting kids, and by animal rights organisations for the cruelty inherent in factory farming. But LGP was the first to bring the criticisms together to reveal the bigger picture.

Morris would eventually end up as one of the two defendants in the ‘McLibel’ case. The burger corporation served libel writs on five LGP activists. Faced with a horrendously unfair and expensive uphill battle, three of the five reluctantly ‘apologised’.

But Morris and Helen Steel, with the ‘pro bono’ support of young barrister Keir Starmer behind the scenes, refused to do so. So the case went ahead and eventually became the longest and one of the most controversial in English legal history.

The McLibel Support Campaign organised practical support for the defendants, raised funds, helped trace witnesses, generated huge support and much publicity, called a range of ‘days of action’ protests (including a national march) and, perhaps most importantly, launched a coordinated and successful defiance effort to ensure anti-McDonald’s leaflets would continue to be distributed outside McDonald’s stores in their millions all over the UK and throughout the world.

In summary, the McLibel case ran from 1990-2005, encompassing the longest trial in English legal history. Morris and Steel, the ‘McLibel 2’, were denied Legal Aid and jury trial. They represented themselves at 28 pre-trial legal hearings, some lasting as long as 3 days. The trial itself consisted of 313 days from 1994-1997, interspersed with 7 trips to the Court of Appeal.

They again represented themselves at their Appeal in 1999, which lasted 23 days.

The ‘McLibel 2’ finally got legal aid for taking the British Government to the European Court of Human Rights where they were formally represented by Keir Starmer.

In the end it was ruled that McDonald’s:

- ‘exploited children’ with their advertising

- produced ‘misleading’ advertising claiming their food was ‘nutritious’

- regular customers faced an increased risk of heart disease

- were ‘culpably responsible’ for cruelty to animals

- were ‘antipathetic’ to unionisation

- helped to lower wages in the catering industry

It was also ruled that it was true or fair comment to say McDonald’s workers suffered poor pay and conditions.

And in 2005 the European Court ruled that the UK government’s defamation laws had breached Steel and Morris’s fundamental rights to a fair trial and freedom of speech.

But there was also a shocking and sensational hidden story waiting to unravel…

Morris described how in 1984 LGP first produced a short and semi-spoof flyer ‘The Sawdust People’ – shown on the Inquiry screens – calling for protests against McDonald’s.

Morris’s only contribution had been to write by hand the words ‘Campaign for Real Life’ in a corner.

Incredibly, in response, LGP received a letter from McDonald’s threatening legal proceedings if certain statements about McDonald’s weren’t withdrawn. The letter advised the group to contact and take heed of others, including Prince Philip, who had withdrawn criticisms they’d made of the junk food multinational.

LGP ignored this letter and the campaign began to take shape and grow.

A number of spycop HN10 Bob Lambert’s reports of anti-McDonald’s protests were brought up, many fantasising about potential disorder – which never seemed to have materialised.

Morris explained that ‘disorder’ was never intended, and it would have been counterproductive. As history shows, their protests were about distributing leaflets and communicating with the public.

However it was clear a more coherent and detailed leaflet would be needed.

The Inquiry then brought up on screen a personal letter from Lambert to Martyn Lowe, dated 22 April 1986.

In it, Lambert asked Lowe, a librarian, to help him track down a copy of a US book ‘Big Mac: The Unauthorized Story of McDonald’s‘ by Max Boas and Steve Chain. This book was a vital source of information for a new ‘What’s Wrong With McDonald’s? Everything they don’t want you to know’ Factsheet, which Lambert was clearly helping to research and write.

In fact Morris held up the actual book, which had been obtained in 1986, and passed on to him years later for research in the build up to the McLibel trial. He read out a key passage in the book about McDonald’s paper packaging, and showed how it had found its way into the Factsheet almost word for word.

Morris referred to other witnesses who recalled Lambert boasting about and being very proud of his role in writing this Factsheet, usually carrying copies around with him.

Lambert has recently tried to play down his role, but in the extensive interview he gave to Channel 4 TV broadcast in October 2011 after Morris and other members of London Greenpeace had publicly exposed him as an undercover police officer, he openly admitted it.

‘I was certainly a contributing author to the McLibel leaflet. Well I think the one I remember making a contribution to was called ‘What’s Wrong With McDonald’s?’

The campaign became very popular. After Bob Lambert ‘handed over’ his deployment in the group to HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’ – and then disappeared himself – LGP began to be also secretly and shockingly infiltrated over an 18 month period by seven private investigators hired by McDonald’s. Some meetings had as many spies as genuine campaigners.

The Inquiry viewed a report of Dines’s from July 1990, two months before McDonald’s served the McLibel writs, noting that McDonald’s were sending ‘occasional interlopers’ to the meetings. Yet Dines later claimed he only found out about McDonald’s hiring private spies after the writs were served!

Dines admitted, in his internal SDS ‘exit’ interview in December 1991, that he knew in detail about the McDonald’s agents who had infiltrated LGP during 1989-1991. Dines says:

‘McDonald’s made mistakes too. Some of their agents were too old, too heavy; others were in too much of a hurry; all were politically unaware… four or five people, employees of a private detective agency, tried to infiltrate LG, but only the last one, a girl, got close.’

It should be noted that the ‘girl’, Michelle Hooker, was an ex-police officer and had a six month sexual relationship with someone in LGP. She stayed in the group until May 1991, 8 months after the writs had been served.

The Inquiry brought up a clip from the McLibel documentary which had been included because it showed McDonald’s private spy Michelle Hooker distributing the leaflet at a 1989 LGP protest outside McDonald’s HQ in Finchley.

It’s of even more interest now we know it also includes undercover officer John Dines (seen in a red lumberjack shirt at 08:35).

Additionally, Morris revealed, just out of shot in the footage was McDonald’s Vice President Sid Nicholson (an ex-Chief Superintendent of Brixton police) and Special Branch officer Brendon O’Hara standing together at a ‘perch’ in the building watching and chatting about the protesters. This had been established during the evidence in the McLibel trial, as was the fact that Nicholson had taken personal responsibility for the hiring of the McDonald’s spies.

During that trial Steel and Morris had uncovered a small part of the scandal after it was revealed that one of the McDonald’s spies had met twice with a Special Branch officer. They successfully sued the Met in 1999 over that alone, and the police settled the case ‘to avoid a difficult and lengthy trial’. But the police had concealed the full, shocking scale of their own spying and high-level collaboration with McDonald’s.

Writs had been served by McDonald’s in September 1990. The week after, Dines reported on what he called a ‘closed’ meeting of the five people named in the writs. He was apparently aggrandising, trying to impress his superiors with his access to private and legally-privileged information.

Morris pointed out that the material must have come to him via Helen Steel, as Dines had engineered a deceitful relationship with her a short time earlier.

Dines later reported on another meeting that the five LGP members named in the writs had with their lawyers.

In that report, Dines asserts that three of them (including Steel and Morris) had very little to do with the leaflet. It raises the question of how much the police had encouraged McDonald’s to sue, who really chose who to sue, and why.

In the first two years after the service of the writs, the most important period in terms of setting the direction of the case, Dines was living with Steel. He was getting details of all the confidential legal advice and strategy following the private legal meetings she and Morris held with their lawyer Keir Starmer.

As Dines admitted in his recent Witness Statement to the Inquiry:

‘It is accurate to say that I was ‘by the side’ of Helen Steel and Dave Morris in 1991 and relaying the legal advice [ie from Keir Starmer] back to my ‘bosses in the SDS’ .’

Dines then faked a ‘breakdown’ and disappeared supposedly abroad. This greatly distressed his partner Steel. Worried about his wellbeing, she began a long search to find him. It was only after years of trying to find him that she discovered the appalling truth that he was actually a police officer.

SHOCKING MISCARRIAGE OF JUSTICE

A Special Branch ‘File Note’ from 18 December 2002 was brought up on screen. It revealed the explosive information that Dines’ name had been ‘deliberately omitted from the McDonald’s libel writ list’ to protect the Special Demonstration Squad. This underlined the blatant interference with and manipulation of the legal process.

In September 1995, with the trial in full swing, Bob Lambert was now managing the Squad. He knew that Helen Steel, still searching for the truth about her disappeared partner, had attempted to contact Dines’s real parents and might be about to discover the facts.

The Inquiry showed an ‘SDS only’ briefing note Lambert authored that bordered on panic about the fact that if Steel confirmed Dines was a spycop then ‘they’ (ie Steel, Morris and Starmer):

‘would give serious consideration to subpoena-ing John Dines and/or the Commissioner to give evidence at the McDonald’s libel case.’

Morris said there was no doubt Dines and Lambert could have been either forced to give evidence during the trial, or been joined to the case as ‘co-defendants’ because of their responsibility for the publication of the McDonald’s Factsheet.

The police would have had to reveal the full truth about the role of the SDS and the entire trial may well have had to have been abandoned as a serious abuse of legal process.

A ‘What’s Wrong With McDonalds?’ leaflet

Morris said that fundamentally, the Met had collaborated with McDonald’s at a high level and in doing so it had misled not just the defendants and Keir Starmer, but also the High Court, the Court of Appeal, the House of Lords, and the European Court of Human Rights. It was a massive miscarriage of justice organised and covered up by the police.

The damning evidence about McDonald’s and general publicity around the trial made the increasingly controversial lawsuit backfire on McDonald’s spectacularly. It was described as ‘the worst corporate PR disaster in history’. People around the world printed and distributed anti-McDonald’s leaflets in huge numbers, making it probably the most famous and well-distributed leaflet ever published.

In March 1991, a secret police report by Dines said that LGP had then been reduced to mainly just four activists. Morris confirmed that the McLibel trial had taken everybody’s effort and focus and the wider group had significantly dwindled.

This, he said, is one of the reasons that corporations and others sue campaigning groups, to tie them up in long and complicated legal action, to put them out of business, to eradicate criticism. He noted that even Parliament recognised this as there was currently a bill going through to try to prevent vexatious litigation in future.

SNEERING LIES AND CYNICAL ABUSES

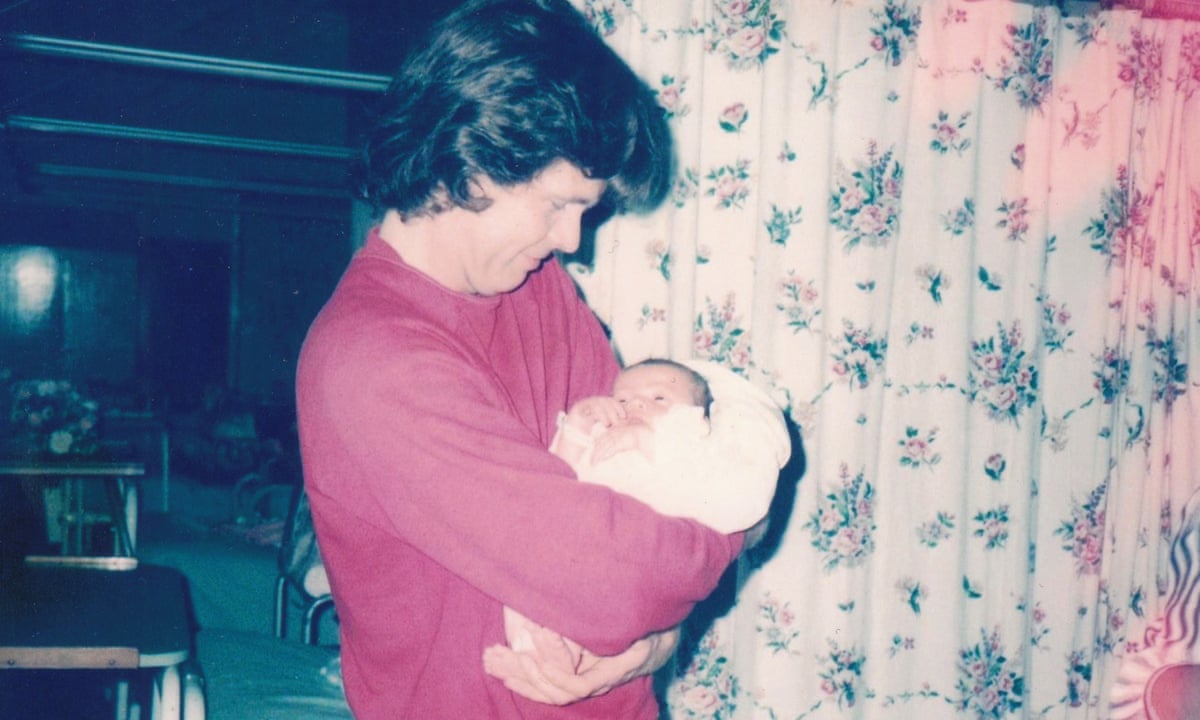

By 1989, Morris had become a new parent and so had less time to commit to London Greenpeace. He’d also become very active in the new and fast-growing anti-poll tax movement.

Spycop HN1 ‘Matt Rayner’ leafleting at an anti-vivisection protest outside a branch of Boot’s

Dines reported that fatherhood had reduced Morris’s activism, claiming he was being forced into ‘occasionally undertaking’ parental responsibilities reluctantly.

Morris was aghast, decrying the description as ‘absolute lies’. It was clear that Dines just couldn’t resist slagging him off for no reason whatsoever. Morris told the Inquiry that he had co-parented for the first two years and then been a single parent for the next 18 years.

During the McLibel trial, supporters organised a rota for childcare for Morris’s son. His next door neighbours did some of that in his house. It just so happens that spycop HN1 ‘Matt Rayner’ deceived a woman activist next door into a relationship and was thereby able to access Morris’s home.

At the same time, HN5 John Dines had engineered the shocking long-term fake partnership with Helen Steel and they were living together in a flat that he’d rented in Tottenham. It just so happened to overlook the family home of Winston Silcott who’d been framed for the murder of a police officer during the Broadwater Farm riot/uprising. The family were campaigning for justice, and Winston eventually had his conviction quashed.

It’s a snapshot of the cynical and shocking tactics with which the out-of-control spycops were able to use and abuse people, invading lives and homes.

POLL TAX

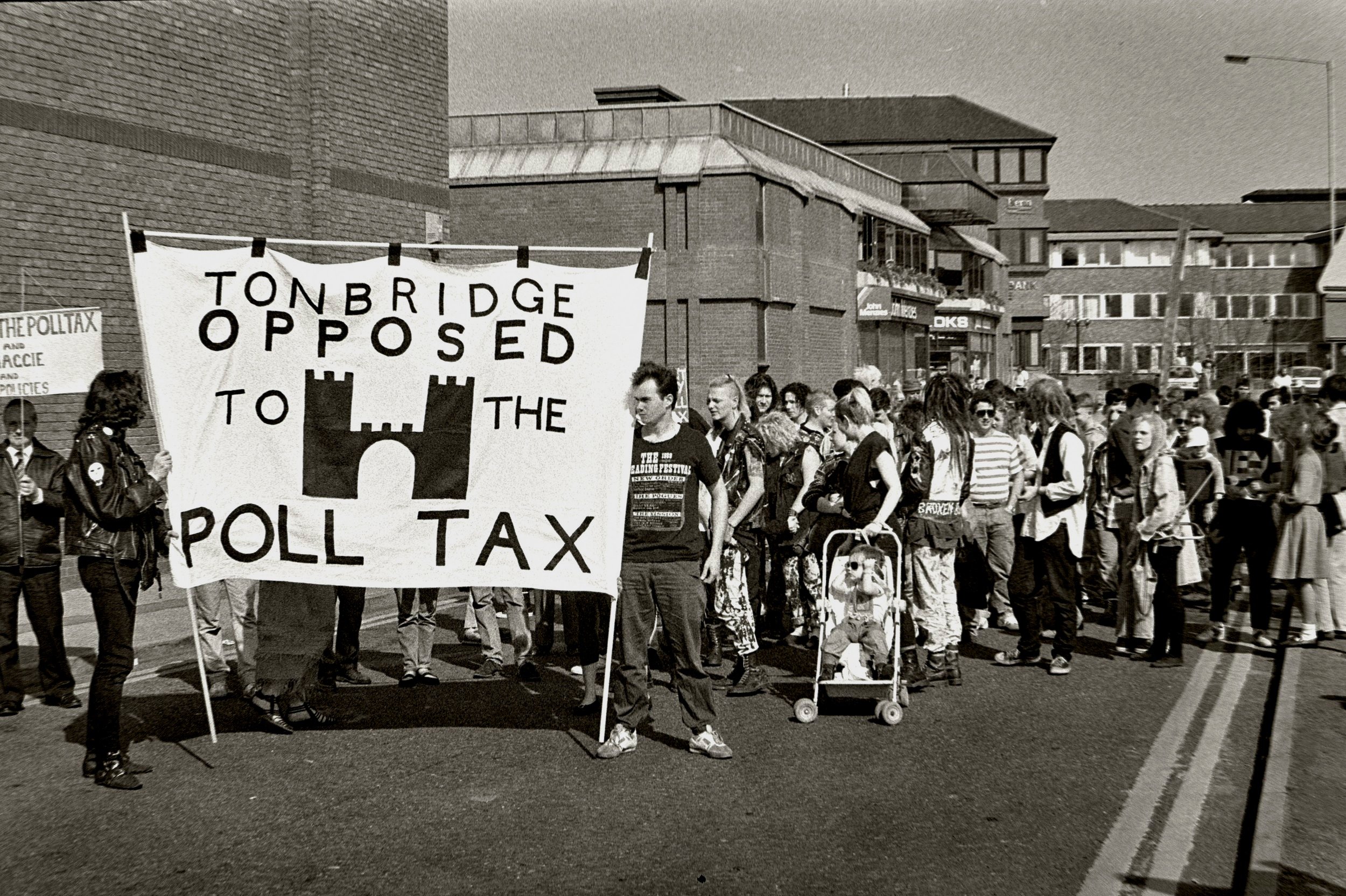

Tonbridge protest. Hated across the country, the poll tax inspired protests in places not normally noted for political dissent. (Pic: Gavin Sawyer)

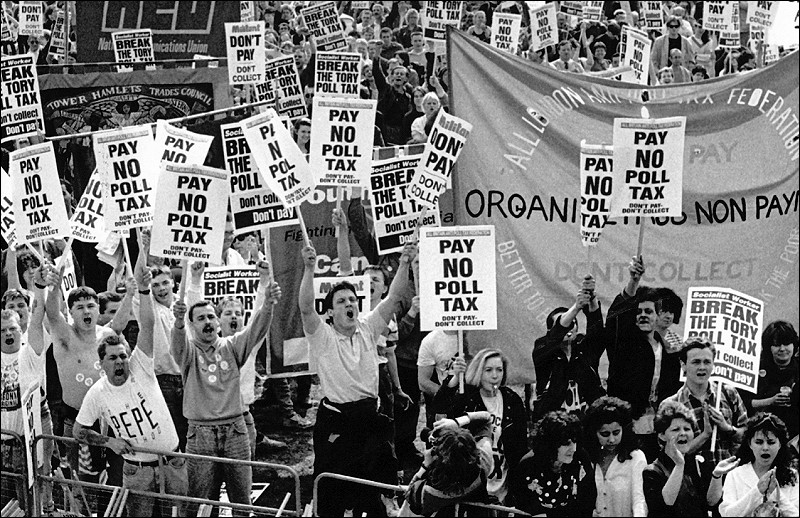

The poll tax was one of the most unfair and hated policies of the Thatcher government (and that’s quite a crowded field). The Prime Minister had called it her ‘flagship policy’. It replaced local council rates – taxation based on property value – and replaced them with a fixed charge per person. A family of four adults in a terraced house would pay four times as much as a single person living in a mansion.

Morris is the only witness to testify to the Inquiry about the epic and historic struggle to scrap the tax. He helped set up Tottenham Against Poll Tax (TAPT) from 1988. The group organised weekly stalls in the high street and distributed tens of thousands of leaflets door to door.

There were thousands of local groups being established across the country, and TAPT – especially as part of Haringey Anti-Poll Tax Union (HAPTU) – was strong and influential, helping to bring together and coordinate the London and national campaign.

TAPT, with Morris as its delegate, was the secretarial group of the London Federation. Morris and HAPTU activists had a key role in organising the first national meeting of anti-poll tax groups in the summer of 1989.

The movement called on people not to register for or pay the Tax, and council workers not to collect it. There were hundreds of large and angry demonstrations outside local town halls (including 1,000 people in Haringey which set the highest charge to pay in the whole country), and people publicly burning their bills.

Morris was asked about the 200,000-strong demonstration on 31 March 1990, on the eve of the Poll Tax implementation the following day.

Undercover reports revealed that SDS officers had met up to ‘pool’ their ‘intelligence’ and had forecast around 20,000 to attend. It was at least ten times that. This was a massive failure by the SDS, and may well have contributed to what became one of the most significant incidents of public disorder of the 20th century.

Morris explained how it further highlighted the SDS’s inability to comprehend what they infiltrate. They’re obsessed with finding individuals and leaders, and sinister or secret plots. They can’t bring themselves to believe that ordinary people can have genuine valid concerns and then mobilise themselves in huge numbers. Radical groups are, he said, a small but useful support to wider movements, no more and no less.

The peaceful and festive demonstration ended in a riot in Trafalgar Square and the surrounding streets. Morris explained that the general view was that the police had provoked the demonstrators and then completely lost control with police vans and horses driving into demonstrators.

Spycop John Dines was at Trafalgar Square that day too, and was arrested with marbles (apparently to use as missiles, or to throw under police horses so they couldn’t run – a controversial tactic generally opposed by most activists). Morris knew nobody else who’d taken marbles.

Dines boasted to activists about his arrest and wrote an account, openly published at the time, saying he had been ‘beaten up’ by police.

TRAFALGAR SQUARE DEFENDANTS CAMPAIGN

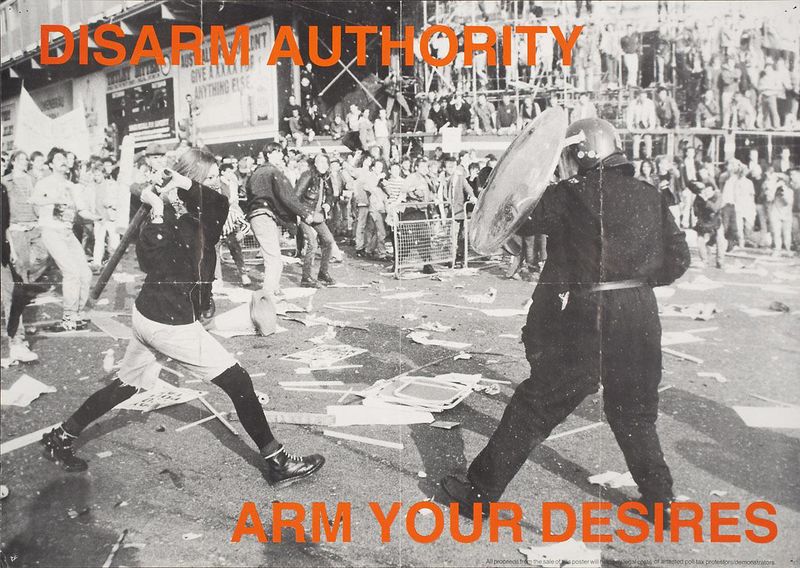

Poll Tax poster – ‘Disarm Authority Arm Your Desires’ – designed & distributed by spycop John Dines to raise funds for those who, like him, were arrested at Trafalgar Square

About 500 arrests were made. Morris was active in setting up the Trafalgar Square Defendants Campaign (TSDC) to support those arrested, and to reassure the movement that it wasn’t going to be terrorised or divided by government or media hysteria.

The TSDC played a vital role in maintaining the unity, solidarity and resolve throughout the ever-growing movement in the face of repression of protests and jailings of non-payers (which he recalled was maybe around 2,000 people).

Morris described media attempts to split the movement into ‘radical’ and ‘moderate’ factions, a division he said was false. This also seems to be a classic SDS tactic, if not its very purpose for existing.

At this point in the hearing, Morris paid tribute to Alistair Mitchell, one of the key people who’d set up the TSDC. He had been due to give evidence to the Inquiry but sadly had passed away in 2019.

Mitchell had been arrested at Trafalgar Square for complaining to police who were assaulting a demonstrator. He himself was then assaulted and arrested, and later found guilty of ‘biting a police officer’.

However, this was overturned on appeal as expert evidence proved that the photos of the ‘bite’ showed the teeth marks could not have been Alistair’s – this case achieved notoriety as ‘the only person in British history convicted for biting a police officer with someone else’s teeth’ – presumably the police officer had done it himself to frame Mitchell. Mitchell later qualified as a barrister.

Minutes of the second TSDC legal meeting, held at the Haringey Unwaged Centre on 10 May 1990, were taken by Morris and shown on screen at the hearing. The meeting was well attended by defendants and solicitors in order to discuss legal matters and strategy.

Dines attended as a ‘defendant’ although later documents revealed that a police Commander ‘pulled’ his case to protect the SDS and the case’s documentation was ‘destroyed’. Once again, the SDS perpetrating an abuse of legal process.

At the end of the minutes, which were circulated throughout the whole movement, Morris had written that the TSDC would ‘expose how the police rioted and ran amok in Trafalgar Square, and ensure that protests and non-payment of the Poll Tax will defeat this hated government measure’.

The movement continued to grow. In Haringey there were 20 local neighbourhood-based solidarity groups at one point, every home in the borough was leafleted 3 or 4 times, and 97,000 were refusing to pay despite threats, widespread use of bailiffs, and even jailings of non-payers. Across the country it was estimated that there were 14 million non-payers.

Morris criticised the poor quality of Dines’ reports on the TSDC and the movement. These unprofessional and inaccurate reports, like so many SDS reports, fixated on sneering at and slagging off personalities, and mischaracterised and underestimated the campaigns and movements they were part of. Dines was obviously trying to impress his bosses and MI5, aiming to justify the continuation of the SDS.

Poll Tax protest (Pic: Dave Sinclair)

The media continued its attacks on the anti-poll tax non-payment movement, and there were calls for a ban on future poll tax demonstrations in central London. The TSDC, however, was determined to defy this pressure and persuaded the London Anti-Poll Tax Federation to organise a march to Brockwell Park on 20 October 1990. 20,000 people attended on the day.

The TSDC itself organised a 1,500-strong protest beforehand at Horseferry Road Court where poll tax cases had been prominent. It was thought to have been one of the largest court pickets of the 20th century, and was followed by a ‘feeder march’ to join the main rally. After the rally the TSDC organised a 3,500-strong march to Brixton prison in solidarity with poll tax prisoners there and elsewhere.

Morris explained that the arrangements had been agreed with the police in advance. He revealed that the Commander of the police operation noted to the organisers that there was ‘talk’ from some police that they (the police) were looking for a ‘re-match’ for what happened at Trafalgar Square. He assured all that this ‘would not be tolerated’.

TSDC took no chances and arranged an unprecedented, sophisticated and full scale monitoring and videoing of the events.

The day had gone to plan until the end when the TSDC march halted outside Brixton prison as agreed. An hour before the large crowd was due to disperse police started to get aggressive.

Morris was the key TSDC coordinator present at this point and tried to find a police commander to restrain his officers – but all senior police personnel had mysteriously disappeared. The police attacked the crowd, including truncheoning Morris on the head. Inevitably this led to a battle and many arrests.

The police issued press statements blaming the demonstrators and there was more predictable hysteria from MPs and the media calling for bans on future demonstrations. But a week later the TSDC held a press conference to reveal a detailed dossier on what had really happened. This got a lot of publicity, and the Met were forced to launch ‘an investigation’.

THATCHER FORCED TO RESIGN

With alarm growing in the Conservative Party about the poll tax, including them losing some ‘safe seats’ due to this issue, Margaret Thatcher was forced to resign in November.

The anti-poll tax movement planned another national march through Westminster on 23 March 1991. The TSDC booked Trafalgar Square. The stakes were very high. This was John Dines take on it all:

‘anarchists and “travellers” alike are just occasionally realistic and recognise that they are unlikely again to create mayhem and destruction in Central London without facing the consequences from a Police Force whom they expect to be buoyed up for retribution’

As Morris explained, aside from showing that the police think in vengeant terms, this ridiculous ‘analysis’ was completely wrong. In fact nobody on any side wanted to get the blame for any breakdown in ‘public order’ and what that might lead to.

Tensions mounted in the weeks before that until, just two days before the march, the Prime Minister, John Major, announced the poll tax was unenforceable and would be scrapped. As a result the demonstration was re-christened a Victory March, much smaller numbers attended, and there were no incidents at all.

TSDC continued in its defence campaign work for the next couple of years, and Morris was then able to properly focus on the McLibel case during its very many pre-trial legal hearings.

Wednesday 6 November 2024

Evidence of Chris Baillee

Click here for transcripts and written evidence

Chris Baillee gave his evidence remotely, and was questioned by John Warrington. He was in very poor health but was determined to contribute to the Inquiry to help it understand the truth about the issues and how he was manipulated by Lambert.

He has supplied a written witness statement to the Inquiry but this still hadn’t been published before this summary was written.

Baillee has supported animal rights for many years. He became politically active around 1980, handing out leaflets and attending meetings, and later got involved in things like graffiti. He described himself as an anarchist.

As a committed vegan, he was also committed to only taking non violent direct action.

He didn’t want to risk harming any animal (and specified ‘humans are animals too, as far as I’m concerned’) and says he was ‘totally against’ the use of incendiary devices. Everyone knew his views.

Spycop HN11 Mike Chitty ‘Mike Blake’ undercover in the 1980s

In 1986, a Daily Express journalist, Eileen McDonald, published a sensationalised account of her alleged infiltration of a secret Animal Liberation Front (ALF) ‘cell’. HN11 Mike Chitty ‘Mike Blake’ included a story in his report [UCPI021974] about her joining Baillee and others at a demonstration against the use of animals in a circus.

Baillee remembers that he and other animal rights activists had to intervene at some point to prevent this reporter from being beaten up by circus ‘heavies’. He also says the activists realised that she was a reporter pretty early on, and said things ‘to wind her up’.

When he wrote his witness statement, Baillee was asked by the Inquiry to list the groups that he was involved in during this era, and comment on whether or not they advocated or supported public disorder, violence, criminal activity or the overthrow of parliamentary democracy. For the most part they didn’t. They did exercise their right to protest, which led to some ‘low level public disorder’, and might have occasionally obstructed the highway.

Class War was an exception. But Baillee says he never got involved in any of their public disorder or violence. He mostly just wrote articles for their newspaper, and went along to a meeting every few months (in marked contrast to what Lambert says about him going to political meetings and protests seven days a week!).

The Inquiry went through some of the reports they had uncovered relating to these groups.

Another report by Chitty [0746458], about a South London Animal Movement (SLAM) meeting in January 1985, described Chris Baillee as an ‘ageing punk anarchist’. SLAM aimed to raise awareness of the mistreatment of animals, and often leafleted and demonstrated outside slaughterhouses, fast food restaurants like McDonald’s and Wimpy. Baillee said that the police sometimes turned up and ‘stopped people protesting peacefully’.

Chitty also reported on the Streatham Action Group, a small closed group of friends who met up every month or so in each other’s houses. There was a leaflet attached, calling for autonomous, localised ‘Stop the City’ style protests to take place on 30 April 1985.

Bailiee was part of this group for around three years, until he moved away from the area up to North London. He rejected Chitty’s description of it as an ‘anarchist’ group, saying its members had a mixture of politics (some were even Labour Party members!).

They sometimes organised public speaker meetings, they put out a magazine, they advertised demos and political campaigns. He laughed off the report’s suggestion that he was responsible for the line ‘stop business as usual’, saying it came from London Greenpeace:

‘I can’t take the credit for that’

Chitty also reported that Baillee and his ‘girlfriend’ were both very involved in a growing campaign against the Leydon Street Slaughterhouse. He points out that this woman was not his girlfriend, she was just one of his housemates. And he wasn’t ‘part of this team’ coordinating the campaign. He says he wasn’t an ‘activist as such’, he only went along occasionally. He recalled that some of the protests started becoming ‘weird and anti-Muslim’ and this put him off going.

The Fur Action Group (FAG) would organise leafleting and sit-ins at places that hosted fur fashion shows or sold fur products. Baillee sometimes took part. All the group did was sit still but this made it hard for shoppers who wanted to look at the furs, and tended to annoy the fur store owners. The owners soon hired security guards and ‘heavies’ and as a result there were some ‘scuffles’.

HUNT SABOTEURS

We moved on to hear about hunt sabbing, and reports written by HN10 Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’. London Greenpeace activists often took part in this lawful form of direct action. Hunt saboteur groups from across South-East England often tried to coordinate their efforts and work together.

As the reports show, the police frequently stopped and searched their vehicles, using road blocks and even a police helicopter to prevent them them from getting near the hunts. ‘Heavies’ associated with the hunts were known for their extreme violence, and as one police report makes clear, had ‘hospitalised’ animal rights activists in the past.

These reports are written in Lambert’s typical style, and contain such unfounded notions about the sabs, such as ‘they might, for once, have shaken off their pacifist inhibitions’. He claims that some ‘chose to carry offensive weapons in their vehicles’ and says that some were arrested for public order offences.

Baillee said that he went sabbing regularly for around two years. Sabs tried to get in the way of the hunt, using scents to distract the hounds. He never saw a hunt sab using any kind of weapon, saying:

‘I would never dream of being associated with anyone who used a weapon at all, because I am very anti-violence’

He was badly beaten by hunt heavies, hired from a local rugby club and armed with sticks, and had to have stitches to his lips in hospital. Baillee rejects Lambert’s suggestion that he knew anything about an incendiary device being planted outside the home of the Master of a controversial hunt.

Hunt saboteurs from the New Forest and Winchester protect a fox earth from the New Forest Foxhounds

Baillee was part of a short-lived group called ‘Anarchists for Animals’ (AFA), explaining that it had been set up as a result of some anarcho-punks not feeling at home in some of the more mainstream animal rights groups. He rejects the idea that he was a ‘founder’ though.

LONDON GREENPEACE

He regularly attended London Greenpeace (LGP) meetings. He went to some London Boots Action Group demos against animal testing. He admits to acting on his own initiative and sometime doing graffiti (on butchers and fur shops, for instance) but wouldn’t describe himself as ‘ALF’.

Another report describes Chris Baillee as having ‘close links with Ronnie Lee’, the ALF founder who was on remand at the time. He says he didn’t visit Ronnie in prison, as it claims, but went there to visit someone else. They weren’t close at all.

He is not happy about all these reports, emphasising that you can’t believe what trained liars like Lambert say. However the description of him being ‘one of the most energetic anarchists in London’ may well have been true! He comes across to observers as incredibly sweet and caring.

Chris Baillee was reported on by multiple Special Demonstration Squad spies.

Baillee has a vague memory of the name ‘Mike Blake’ but can’t remember much about him. He now knows this was the cover name used by HN11 Mike Chitty, and thinks he would probably have seen him in the pub after a SLAM meeting. He says he wasn’t aware of the relationship between him and ‘Lizzie’.

He had no memory of anyone called ‘John Barker’ (a name used by another of the undercovers, HN5 John Dines). He knew Helen Steel, but never asked her about her personal relationships, so didn’t know she and John were a ‘couple’.

He remembers HN1 ‘Matt Rayner’ quite well. But didn’t know him very well, and had no knowledge of the relationship he had during his deployment, with Liz (or Denise) Fuller. He admits that he never paid much attention to other people’s relationships!

‘I wasn’t very keen on relationships. They come and go’.

He met HN10 Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’ at London Greenpeace meetings, at which they were both regulars. ‘Bob’ was involved in many of the same groups as him, and Baillee recalled that ‘he used to take us all over the place in his van’, never asking for money.

He got the impression that ‘Bob’ helped out with the Animal Liberation Front Supporters Group (ALFSG) when Ronnie Lee was away, and says he was always ‘trying to get involved with as many people as possible’. He remembers him as seemingly a ‘likeable character’, but also ‘a very persuasive person’.

As time went on, he ‘became more dominant. He started to suggest things’. One such thing was the idea of demonstrating at Murray’s meat market in Brixton. This led to five activists appearing on trial at Camberwell Magistrates’ Court.

Baillee is listed as having appeared as a witness in this case. ‘Mark Robinson’ (another pseudonym used by Lambert) was one of the defendants. Baillee doesn’t have any recollection of ‘Bob’ giving evidence at this or any any court case.

He does remember ‘Bob’ organising benefits for the ALFSG, including one with the band Chumbawamba.