UCPI Daily Report, 16 May 2022

Tranche 1, Phase 3, Day 6

16 May 2022

Witnesses:

Bill Furner

David Smith

Roy Creamer

The sixth day of the Undercover Policing Inquiry hearing evidence concerned with the Special Demonstration Squad’s managers 1968-82 began with a summary of William Furner’s statement being read out. He was a founding member of the Squad in the summer of 1968.

This was followed by live evidence from David Smith (officer HN103). The afternoon was taken up by Roy Creamer (officer HN3093), present by video link.

The Inquiry also published many documents today relating to other early managers who are now deceased: Conrad Dixon (officer HN325, founder of the Squad), Phil Saunders (officer HN1251), and Riby Wilson (officer HN1748).

Bill Furner

In his first statement, Bill Furner (officer HN3095), a founding member of the Metropolitan Police’s Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) had helped the Inquiry to identify people in photos taken at the SDS Christmas party in 1968. His second statement dealt with his job in the back office of the SDS.

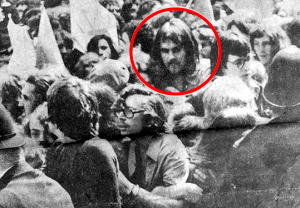

Anti-apartheid activists block the coach taking the Springbok rugby team to Twickenham, December 1969

Furner supported the first group of undercover officers, who infiltrated left wing groups preparing for the October 1968 demonstration against the war in Vietnam. Based at Scotland Yard, his job was administrative.

For instance, he checked officers’ expenses against their diaries, made sure they “paid their rents and that it was all genuine and above board”. He did not deal with cover identities, cars or houses.

He was present at the meetings held at the undercover flat, which all officers came to in order to hand over their diaries and reports, and to talk about who was attending upcoming events.

Occasionally, he also attended meetings and demonstrations, remembering ones at Trafalgar Square and at Twickenham. For these, he was simply part of the audience to make notes; he did not change his appearance other than to wear a scruffy coat.

In his written statement, asked what the SDS achieved for the benefits of policing, his response was that these deployments:

“meant that we had the people under observation and different organisations completely and utterly tapped. They did not make a move that we did not know about. The obvious benefit is that we knew what their aims were.

“For example there was one group that decided to chain themselves to the rugby posts at Twickenham when South Africa were playing. We knew about this, and uniformed police were told to be present with bolt cutters.”

Bill Furner is one of the few officers who says that information from the Security Service (aka MI5) came into their office, implying it was not a one-way street. The next sentence in his statement was gisted as “Reading this information was a major part of my job.”

The SDS had a very close liaison with the Security Service – “we helped each other”.

As Furner added:

“Special Branch were the arm to make enquiries… [we] had the power to effect arrest… The Security Service was divorced from police work.”

First witness statement of Bill Furner

Second witness statement of Bill Furner

David Smith

The appearance of David Smith (officer HN103) as a witness was marked by his ability to recall seemingly mundane administrative details about the SDS and an equal inability to recall anything which might be controversial.

He spent considerable time in his post as back-office sergeant in the SDS – from 1970 to 1974, giving him substantial knowledge of the unit’s administrative side.

Like almost all other police witnesses, Smith claimed he knew nothing about the sexual relationships that officers had whilst undercover. When queried on this – and characteristic of the roundabout way he answered questions – he started musing about there being fewer women involved in radical groups in those days, with the exception of the Women’s Liberation movement.

In his witness statement, Smith was more critical, saying it was “wrong and foolish”, as it posed a risk to the Squad – and obviously had an impact on the other parties.

“Some more wrong than others, but it was wrong, full stop.”

Unlike some of the witnesses we have (and will) hear from in this set of hearings, Smith was adamant that the SDS decided which groups they would target – and that the Security Service did not tell them what to do. He suggested that there was not much interference from outside the SDS. “We knew what we had to do” – “in many ways” the operation ran itself.

Special Branch relied heavily on the two senior SDS managers to oversee the unit – they decided on who was targeted, according to Smith. Unfortunately he wasn’t pressed on this topic, even when he contradicted himself, saying that Special Branch’s C squad advised on tasking.

Later, Smith said he often took Special Branch Registry files about individuals to the safe house, with a note asking the officer in the field if they could assist with information about these people.

Smith also says that right wing organisations weren’t appropriate targets for the SDS at that period in time, not worth infiltrating. However, by the time he had become a Chief Inspector in C Squad in the late 1970s and early 1980s and was responsible for right-wing and animal rights groups, that had changed and he had “put up” an argument for spying more on far-right organisations. Any final decision about targeting would have been made by the Chief Superintendent or similar.

“COMMON SENSE”

As with most officers, when asked whether there was any proactive attempt to advise officers not to become sexually involved with their targets, Smith said it was simply “common sense” not to do so. Obviously, not for everyone.

While there was no official training, Smith said the main thing that was “hammered home” to SDS officers was to avoid being an agent provocateur:

“We wanted them to be a fly on the wall not to be taking a leading part in things.”

He also said there were some organisations which were “pretty common throughout” meaning they were always spied on), then others “sort of came and went”. They adjusted their coverage accordingly, with “the advice of the rest of the Branch … it naturally evolved”.

Most of the undercovers had already spent three or four years in the Branch, so had a good idea about the organisations being infiltrated. He described their “rolling programme” – those whose deployments were ending could give very valuable advice to those whose time undercover was about to start.

The SDS was well-established by the time he joined in 1970: it had become a permanent unit subject to annual review. He was not worried about it being curtailed, saying:

“I thought it would go on as long… as it remained a secret”.

In Smith’s view, if a tactic is proven to be effective, you do not get rid of it.

ENDS JUSTIFY THE MEANS?

Smith said the SDS was necessary because it ‘sharpened’ things to get accurate numbers on demos to inform public order policing levels.

He then explained that joining a less extreme group, such as the Young Liberals, could provide a useful “stepping stone” and give some “street cred”, which would enable an officer to join more radical groups without seeming suspicious.

One officer, ‘Michael Scott‘ (officer HN298, 1971-76) did so and went on to infiltrate anarchist and Irish groups and the Workers Revolutionary Party, for example.

Next, Smith was asked how SDS reports were processed. He told the hearing that he received bundles of handwritten reports from the spycops. Sometimes information also came into the office by telephone. His job was to collate and put them in the standard format for typing up by the typing pool (which was next door).

Kevin Gately in Red Lion Square, London, shortly before he was killed, 15 June 1974. Smith is the latest spycop to suffer selective amnesia about this event

He denied doing any “sanitising” or analysing – he says he was aware enough to recognise if anything “needed to be expedited.”

The next moment he said that sometimes he did “slightly sanitise” reports, getting rid of some specific details and making them “less precise” in order to send them to A8, which was outside of Special Branch. He said this was his “common sense” – nobody needed to tell him to do this, he just “instinctively knew”.

C Squad, the part of Special Branch which oversaw operations against left wing groups, prepared threat assessments for A8, which dealt with public order. The Inquiry suggests that they did 600-700 of these per year – this would have equated to 10+ every week. Smith was not surprised by these figures.

SDS intelligence would have been “woven into” these assessments – he says the unit helped by “padding out the juicy bits,” and being able to provide more precision in terms of numbers and the likelihood of violence. (The role of Special Branch Liaison officer was created at some point around this time, to “help A8” understand enough and act appropriately, while protecting the source of the information.)

Smith thought that about 50-60 SDS reports would have been written in the course of a week, of which around 75-80% went to the Security Service, adding “we didn’t send them the Irish stuff”.

He agreed with Geoff Craft (who we will hear from on Wednesday) that no other police officers were more closely monitored than the SDS officers. Monitored for what exactly? we may ask!

Unconvincingly, Smith says he cannot recall what happened at Red Lion Square in 1974. He was slightly too fast to say the name rang a bell, but that was all. It is quite unlikely that he can’t remember the death of Kevin Gately at a demonstration against the fascist National Front. Gately was the first person to die on a demonstration in England for decades – and to prevent such public order problems was the SDS’ ultimate reason for existing.

PICKFORD AND CLARK

‘Jim Pickford‘ (officer HN300) and Rick Clark (officer HN297) were both recruited as Smith was leaving the unit. Both men were known as ‘womanisers’ within Special Branch. Had he known at the time, he would have advised against recruiting them to the SDS, he now says.

Asked for his view about the sort of person who was suitable for undercover work, Smith said they needed to have a “balanced, calm disposition.” Otherwise, he kept his opinions about the spycops he worked with to himself.

Smith wasn’t hugely concerned about spycops being arrested and going to court – it didn’t happen very often – he can only recall one incident of an officer ending up in court and testifying under a false name. He agreed that “technically” this did constitute misleading the court, but also talked about “different degrees” – and drew upon an unconvincing analogy about speeding to suggest it was not all that serious.

Smith returned for some supplementary questions after lunch but said nothing of consequence.

Written statement of David Smith

Roy Creamer

Roy Creamer (officer HN3903) was an eagerly anticipated witness in this phase of the Inquiry. Originally, the Inquiry’s Chair, Sir John Mitting, had not planned to call Creamer to give live evidence. But after representations were made by non-state core participants (ie victims of spycops) Mitting relented and agreed that we should hear from him.

Though the former Special Branch manager is in his 90s, Creamer was well able to provide a detailed account of his time, his memory often better than younger colleagues.

He was questioned by Counsel to the Inquiry, David Barr QC.

BACKGROUND

Chief Inspector Conrad Dixon, founder of the Special Demonstration Squad, 1968

Creamer was involved in the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) at its formation in 1968, when he worked closely with Conrad Dixon. He was later active with the Bomb Squad, where he is best known for having investigated and arrested alleged members of the Angry Brigade. This topic was not touched on today. Later, he returned to C Squad (which deals with left wing activists) as a Detective Inspector. He retired in 1980.

Whereas, so far, many witnesses were relatively new to Special Branch when they encountered the Special Demonstration Squad, Creamer was already an experienced officer of ten years before the SDS was set up in 1968.

He spent much of the decade prior to the founding of the SDS, working on the left wing desks (B / C Squad). This work involved being sent to meetings, to report back on what was heard and look for the next opportunity to report on. At that time, the main focus was on the Communist Party of Great Britain, not the ‘ultra Left’ groups, which were not seen as much of a threat or considered worthy of police attention. This changed as those groups grew in size and strength.

ANARCHISTS

![Albert Meltzer in his bookshop [pic: Phil Ruff]](http://campaignopposingpolicesurveillance.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Albert-Meltzer-1960s-229x300.jpeg)

Albert Meltzer in his bookshop

[pic: Phil Ruff]

The officer talked about his open approach to talking to anarchists, not hiding that he was from Special Branch. This lead to uneasy relationships with Christie, Albert Meltzer and others. He visited Meltzer’s bookshop to read the notices in the window on upcoming anarchist activities.

Creamer said that in his conversations he got very little on the anarchists themselves, but what he did learn about was their attitude to other groups which provided insight into how the different politics intersected with each other.

Barr noted that while the Angry Brigade was clearly of interest to Special Branch, what about Freedom Press, the anarchist publishers? Creamer was clear they were not targets for public order purposes. They were not a force to be reckoned with and were not really up for a fight.

There were ‘so-called anarchists’ who he considered hooligans, who didn’t want to obey anyone including protest organisers and so were a public order issue. He summed up anarchists as difficult to keep an eye on:

“I don’t think we were up for it. They were cleverer than us in many ways.”

TROTSKYISTS & THE ‘EXTREME LEFT’

Next, Barr explored Trotskyists groups such as the International Marxist Group (IMG), International Socialists (IS, later Socialist Workers’ Party) and the Socialist Labour League (SLL, later Workers Revolutionary Party).

Next, Barr explored Trotskyists groups such as the International Marxist Group (IMG), International Socialists (IS, later Socialist Workers’ Party) and the Socialist Labour League (SLL, later Workers Revolutionary Party).

Creamer described them in terms of how disciplined they were and their ability to discipline their members or the protests they organised. They could be difficult to infiltrate, but if you did you would learn a lot about what was going on. Other groups were easier to infiltrate but one learned less.

The SLL were the most disciplined group which actually meant they were much less of a public order issue. On the other hand, the IMG were not prepared to discipline themselves and did not have the will or numbers to particularly marshal their protests. The IS were a threat to public order, but only in the sense they were prepared to organise large demonstrations – which is what mattered from a policing point of view.

On the Maoists, he said that some of them were from the Far East themselves, and there was an uncertainty about their cultural norms. They could be quite loud and emotional on protests, but how much that came from anger over injustice or how much was their natural way was unclear. Given their numbers were small, he wrote that they were noisy and boisterous, but not dangerous, suggesting that a competent group of police could handle any of their demonstrations.

PRE-SDS PRACTICE

Creamer briefly spoke of the far-right in his pre-SDS work. Then they were a mostly discredited group of little interest. Their demonstrations only received attention when attacked by the left.

Barr asked Creamer about the right of entry into a private home, a recurring legal issues in these hearings. Creamer admitted that in normal police work an officer would not go into a house without a warrant. This was the official line, including when Special Branch officers were sent to monitor meetings. Sometimes it did happen that a plain clothes officer got in, but it happened so rarely people did not think about it as an issue.

They next moved on to an extensive exploration of the usefulness of infiltrating many groups on the left. Creamer in his written statement had been quite critical of the role of the SDS and the unrealistic nature of what it was being asked to in terms of identifying public order issues.

Overall, it was Creamer’s assessment that prior to 1967, the standard Special Branch approach to public order and answering Security Service queries was sufficient, especially given the culture of the time. He was critical of the inefficient organisation and thought the lacklustre reporting back on protests was very weak. The latter was something Creamer actively tried to improve.

In particular, he noted that following a demonstration at the house of the Home Secretary, Roy Jenkins, his commanding officer Victor Gilbert was slammed for not being able to identify those responsible and explain their motivations. Something Creamer resolved.

He also took on Gilbert’s request to improve the quality of intelligence being sent to A8 (the uniformed police’s public order division):

“I felt it was my mission to do that.”

He sought out ways to write reports that would give A8 the correct impression, while noting that it was not possible to quantify the information they wanted, without offending them. For instance, if he thought a protest was going to be ‘lively’, he would up the estimated numbers so there would be sufficient police.

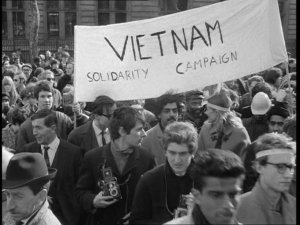

Special Branch’s attitude towards protests changed after the March 1968 anti-Vietnam War protest, which led to the founding of the Special Demonstration Squad.

SPECIAL DEMONSTRATION SQUAD

Creamer was hand-picked by SDS founder Conrad Dixon to play a part at the very beginning of this new Squad. His was almost exclusively a back office role – he says that he refused to be sent undercover, because he preferred to do things in an open way and because he clearly could not have got away with it, being known and recognisable to so many on the left.

He described Conrad Dixon as someone who took on setting up the SDS as an adventure, to Dixon it was difficult work but something he felt he could do. Creamer, in his words, was there to restrain him from ‘doing anything stupid’ – this was a tacit agreement between them.

Creamer helped Dixon with the reports and attended bigger meetings so he had the big picture – which meant that Dixon could tell those higher up the right answer:

“I knew what I had to, and he knew what to expect from me.”

Barr wanted to know if Dixon took legal advice on operating an undercover unit. Creamer was certain he that didn’t and it wouldn’t have been in his nature to do so:

“[Dixon] saw this as a challenge and he didn’t want to be inhibited by any scruples that other people might have because he trusted himself to be scrupulous as the situation demanded, no more and no less, and to be honest, that’s the situation.”

As to his role within the SDS, Creamer did admit that he looked out for the undercovers and helped them with advice. He particularly wanted them to avoid getting arrested, taking drugs, or contracting illnesses (in his words).

Though he conceded the subject was serious, Creamer spoke of the levity the spycops enjoyed as they spied on people and undermined campiagns:

“when we were in that squad, it was a lark in many ways, it was an adventure, and there was no ill will towards the people we were penetrating or whatever. It was an experiment to see if it could be done. That was the theme of Conrad’s police.”

REPORTS

Barr took him through a number of reports which bore his name. Creamer said that while reports were signed by him, that might be a cover for the undercover sourcing the material. Barr pointed out on that the language in the report on the Anti-Imperialist Solidarity Movement was very much the language used by Creamer.

Barr took him through a number of reports which bore his name. Creamer said that while reports were signed by him, that might be a cover for the undercover sourcing the material. Barr pointed out on that the language in the report on the Anti-Imperialist Solidarity Movement was very much the language used by Creamer.

Creamer noted that the two sets of minutes from meetings of the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign’s working committee dated December 1968 could not have been obtained by traditional Special Branch methods.

Of a report which noted that the attraction of the Maoist leader Abhimanyu Manchanda was based on him being willing to take the most revolutionary line, he said that he had to pass on the ‘germ of the ideal’. In fact he thought it would not lead to much, but at that point in time the people around Manchanda fell under the list of groups capable of ‘doing a mischief’.

One unusual report that discussed internal political divisions within the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign coalition remains a bit of a mystery. It was not from an undercover, or an informer, but by a source who knew what was going on. Creamer didn’t want to say more about it, though he clearly knew the origins. He also noted that was of a much higher standard than either he or Dixon could have produced.

VALUE OF THE SDS

The SDS had been established after the police were unprepared for the disorder at a March 1968 demonstration against the Vietnam war. The unit was established to gather intelligence and prevent any repeat in a further demonstration in October 1968.

Police on horseback charge demonstrators against the Vietnam War, Grosvenor Square, 17 March 1968

Barr asked if undercover policing made a difference to the handling of the October demonstration. Creamer was of the opinion that it did in the run up to the day, as A8 received a higher standard of information. But on the day itself, no. It mainly came down to reassuring the powers that be that there was not going to be a violent protest.

Creamer’s most trenchant criticism, both in statement and orally was that the SDS were being sent out to look for evidence of pre-planned violence, which was never going happen. It was an unrealistic request.

He was firm that the SDS should have packed up after October 1968. As far as he was concerned, the unit was ‘hedged around’ with all sorts of difficult problems. Instead, management should have started again properly, picking out the good bits and getting rid of the bad bits. In any case, in his eyes the ‘battle had been won’ in October 1968.

However, the problem was the police were very reluctant to cancel demos outright – it was viewed as more trouble than it was worth. So protests were going to happen in any case. That attitude did not change until the violence at the August 1977 ‘Battle of Lewisham‘ clash between fascists and anti-fascists – which clinched it for Creamer that undercovers were no longer needed.

LATER LINKS WITH THE SDS

After leaving the unit, Creamer had little to do with the SDS directly. He did accept, however, that in his time as a Detective Inspector on the left wing desk in C Squad, he received intelligence that he recognised as emanating from the undercover unit.

Creamer is clear that C Squad did not influence the tasking of SDS undercovers – they had influence, and perhaps a veto, but to the best of his knowledge, C Squad did not use it.

Though he had his own thoughts on how things should be or could be improved, Creamer notes multiple times that any interference from him wouldn’t have been welcomed, so he stayed in his lane. He didn’t want to make waves and didn’t dare interfere with what the later SDS was doing; a fact that’s very iluminating about about Special Branch culture at the time.

Written statement of Roy Creamer

Transcript and video of the morning and afternoon the day’s hearing

The current round of Undercover Policing Inquiry hearings, focusing on Special Demonstration Squad managers 1968-82, continue until Friday 20 May.