UCPI Daily Report, 20 Nov 2025: Doreen Lawrence evidence

Tranche 3 Phase 1, Day 17

20 November 2025

Doreen Lawrence giving evidence to the Undercover Policing Inquiry, 20 November 2025

INTRODUCTION

On the afternoon of Thursday 20 November 2025, the Undercover Policing Inquiry heard evidence from Baroness Doreen Lawrence, the mother of murdered teenager, Stephen Lawrence.

This was a key evidence day for the Inquiry. The Lawrence family’s campaign for justice for their son shone a light on institutional racism in the Metropolitan Police.

The revelation, in 2014, that the Met had sent spies to report on the Lawrence family was the straw that broke the camel’s back in the spycops scandal. It was the trigger that prompted the then Home Secretary, Theresa May, to set up the Undercover Policing Inquiry (UCPI), an independent, judge-led inquiry into undercover policing in England and Wales.

The main focus of the UCPI is the activity of two units who deployed long-term undercover officers into a variety of political groups: the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS, 1968-2008) and the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU, 1999-2011). Spycops from these units lived as activists for years at a time, spying on more than 1,000 mostly left-wing, progressive groups.

Baroness Lawrence has given the Inquiry a written witness statement [UCPI0000038014].

She was questioned for the Inquiry by Sarah Hemingway. The Inquiry’s page for the day has video and a transcript of the live session.

The hearing room was more packed than usual, with several media outlets present, leading to widespread coverage of the hearing at the end of the day (ITVX, The Guardian, The Express).

BACKGROUND – ALL THE INVESTIGATIONS

The Lawrence family have been fighting for justice for Stephen for 32 years. There have been numerous investigations, inquests and inquiries into Stephen’s death and the police response.

In November 1993 there was the Barker review (mentioned in more detail below). An inquest opened on 21 December 1993 which was suspended after new leads came to light. It resumed in February 1997 and found that Stephen had been:

‘unlawfully killed by five white youths in an unprovoked racist attack.’

The family brought their own private prosecution of the five killers at the Old Bailey. On 22 April 1995, the second anniversary of Stephen’s death, a judge issued summonses and warrants to arrest the named suspects.

Doreen Lawrence speaks outside the private prosecution of three of Stephen’s killers

She told this Inquiry that she went into court believing they stood a chance, but it was clear from the first day that the judge was unsympathetic. He did not allow the jurors to hear much of the evidence.

Most of the trial was taken up with technical legal arguments, and the jury were instructed to reach a not guilty verdict. The case was dismissed in April 1996.

Hemingway pointed out that the judge in that case was not criticised in the Macpherson report published at the end of the 1997-8 public inquiry. Lawrence replied: ‘He should have been’.

In 1997, Kent police conducted an independent review of the Met’s murder investigation, following the family’s the formal complaint to the Police Complaints Authority.

Then, in July 1997, the Home Secretary ordered a public inquiry, chaired by Sir William Macpherson.

Macpherson published the Lawrence inquiry’s report in February 1999, and found that the Metropolitan Police were institutionally racist. He defined that as:

‘The collective failure of an organisation to provide an appropriate and professional service to people because of their colour, culture or ethnic origin.

It can be seen or detected in processes, attitudes and behaviour, which amount to discrimination through unwitting prejudice, ignorance, thoughtlessness and racist stereotyping which disadvantage minority ethnic people.’

That definition was raised by the Undercover Policing Inquiry’s Chair, Sir John Mitting, during opening statements to this phase of hearings. He shocked core participants by saying he doubts whether it applies to the work of the SDS because they don’t directly provide a service to members of the public.

Stephen Lawrence as a young child

In January 2012, there was a further review of the killing including fresh evidence. Consequently two of the five killers, Gary Dobson and David Norris, were tried and convicted of Stephen’s murder, almost 20 years after the event.

After several years of shocking revelations in the spycops scandal, in June 2013 it was revealed that the Lawrences had been targeted by undercover officers.

In response, the government set up the Ellison Review into Met corruption in the handling of the Lawrence investigation and the Macpherson inquiry.

The Review confirmed the spying had happened. The fact that it hadn’t been mentioned in any previous proceedings was indefensible. It was the trigger that led to the Undercover Policing Inquiry being announced.

In September 2025, over three decades after Stephen’s murder, the College of Policing was commissioned by the Metropolitan Police to conduct an independent review of the investigation into Stephen’s murder, to determine if there are any outstanding relevant lines of inquiry which can be pursued.

THE UNDERCOVER POLICE

Baroness Lawrence arrived at the UCPI to give evidence to her third public inquiry into the police handling of her son’s death.

The decade that we have all had to wait for this Inquiry to reach this stage pales into insignificance in the face of the thirty years and counting that the Lawrence family have been fighting for truth and justice. Her courage, tenacity and above all, endurance should be an inspiration to us.

Given the number of investigations surrounding the case, Hemingway had to make clear the role of this Inquiry:

‘We have a long line of different investigations, different events that have happened, and it is evident that you are still fighting for justice for Stephen all these years later.

I won’t go into any detail on those previous investigations as I’ve said, but the Inquiry won’t seek to go behind those findings either…

What this Inquiry is interested in is the extent to which matters concerning you, your family, the Stephen Lawrence campaign which was then set up to try to bring his killers to justice, and the groups surrounding the campaign, were reported on by undercover officers.’

Hemingway began by asking Lawrence about her personal background, growing up in Jamaica and coming to London as a child in the 1950s. After leaving school she worked in banking.

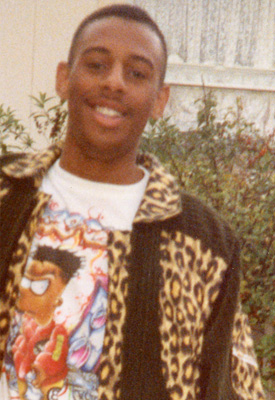

Stephen Lawrence, 1992

She was also asked about Stephen as a little boy. He liked cars, drawing and reading. As he got older he wanted to be an architect. There weren’t many Black children at Stephen’s school, so the majority of his friends were white.

Stephen was just 18 years old when he was murdered in a racially motivated attack while waiting at a bus stop on Well Hall Road in Eltham on the evening of 22 April 1993.

Before going on to look at the police response to the murder, the Inquiry asked Lawrence to explain where she was that night. She explained that she was on a study group field trip to the Black Country as part of a humanities degree.

This question was motivated by a claim made by Special Demonstration Squad officer HN43 Peter Francis in his written witness statement to the Inquiry [UCPI0000036012]. He says he received information that ‘could discredit Doreen Lawrence’ which he passed on to his manager, HN86 (but didn’t write up in a report). The ‘information’ was merely a rumour that she had been out partying the night Stephen died.

The suggestion that her attending a party while her 18-year-old son was doing something else could possibly discredit her is, in itself, offensive, but in any case, it was clearly not true.

POLICE RACISM IN RESPONSE TO MURDER

Lawrence said that she did experience racism in her life. She described the racial prejudice that halted her career progression in banking. However, she had not had any dealings with the police before Stephen was murdered, and nothing had prepared her for what was to come.

Doreen Lawrence found out through Stephen’s friends that, after the murder, the police were going to his school and questioning people: Why was he out that night? Where was he on the way home from? What was he doing?

‘The assumption is that, you know, my son must been a criminal, and that was what they kept bringing up.’

Stephen was a young man with no criminality. The police could not believe that a Black family had had no engagement with the police before their son was murdered. It is perhaps unsurprising. Their racist policing puts so many innocent Black youths in the frame that Stephen must have been comparatively rare.

‘When I heard about the stabbing, the main artery that was severed. I just thought that they would be so outraged that they would want to do whatever they could to bring Stephen’s killers to justice…

They showed no interest whatsoever. And if we hadn’t kept speaking out and challenging what was happening, I think to this day we would never have got any conviction whatsoever…

This is when they start thinking about the racism, because had Stephen been white they would have looked at it completely different.’

MARCHES AGAINST THE BNP IN THE AREA

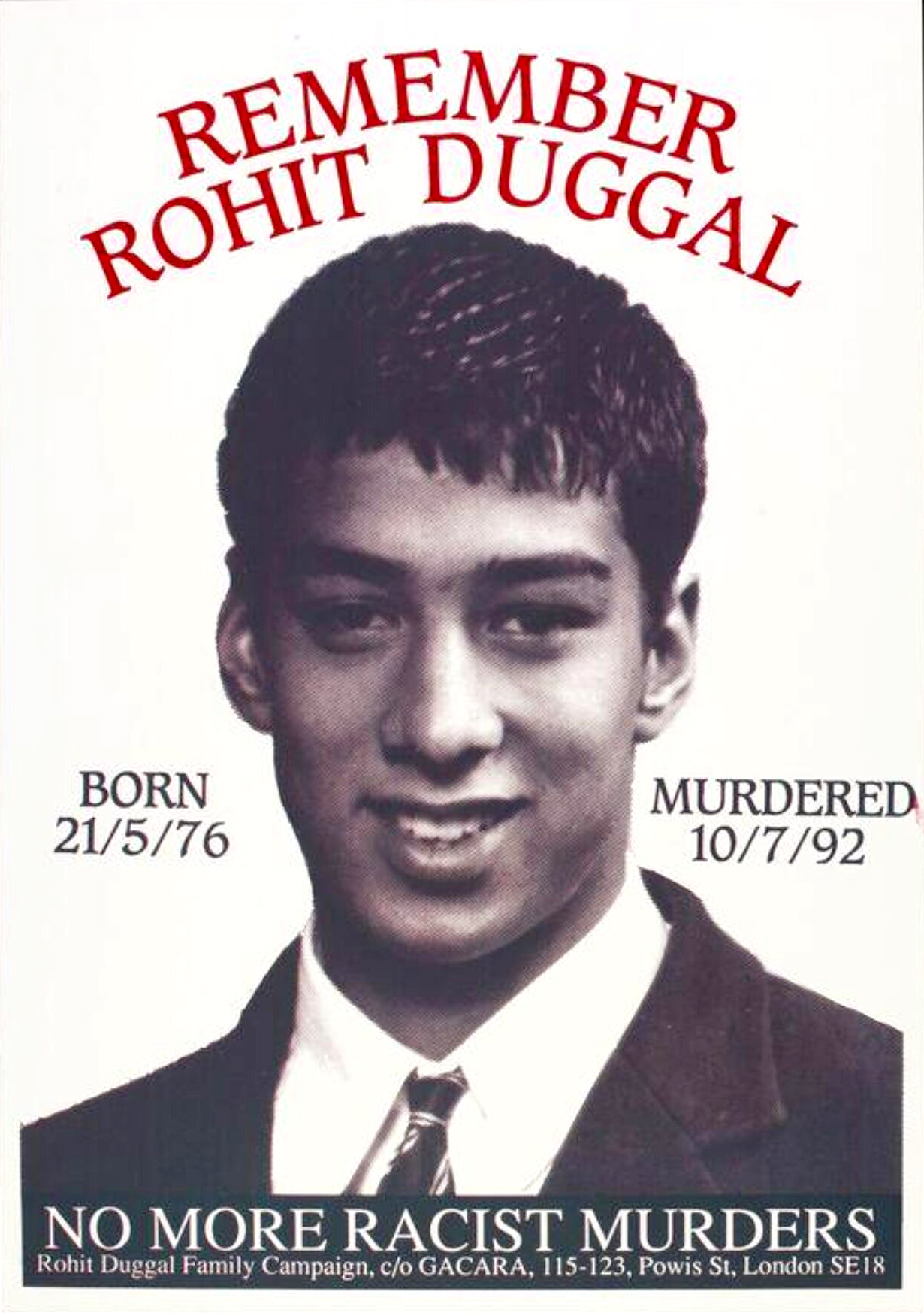

Remember Rohit Duggal poster

Stephen was not the only victim of a racist stabbing in the area around that time. Rolan Adams, Gurdeep Bhangal, and Rohit Duggal were all named as victims.

At the UCPI, we have heard from witnesses like Lois Austin, Alex Owolade and Karen Doyle about the impact of the presence of the British National Party (BNP) in East London.

All spoke of the efforts of the community to protect themselves against a growing fascist threat, including the 1993 demonstrations against the BNP headquarters in Welling.

During Lawrence’s evidence we heard how Stephen’s friend, Duwayne Brooks, who had been with Stephen that night and survived the attack, was arrested after one of those demonstrations.

Brooks attended the Welling demonstration on 8 May 1993 and SDS officers were asked to identify him from photos. He was then arrested for violent disorder. Lawrence pointed out how inappropriate this was:

‘Rather than them investigating Stephen’s murder they wanted to discredit Duwayne…

Duwayne was the witness, then he should be able to tell the police exactly what happened on the night and so by singling him out in the way in which they did, what they’re trying to do is to discredit anything that he had to say.’

Brooks was twice prosecuted on charges so ludicrous that the case was dismissed by the judge as an abuse of process without Brooks having to even speak. This is so exceptional that there is no other person known to have had this type of dismissal twice.

OVERT RACISM IN THE SDS

Regarding anti-racists and anti-fascists as a problem rather than racism and fascism has been a baked-in feature from the start of the Special Demonstration Squad. It has deployed many more officers into anti-racist groups than into racist ones, and even targeted campaigns against apartheid in South Africa.

We saw evidence of overtly racist comments being made by SDS managers like HN86 and his boss, HN593 Superintendent Bob Potter.

In his written witness statement to the Inquiry [UCPI0000036012], whistleblower SDS officer HN43 Peter Francis maintains:

‘The Special Branch attitude towards the Lawrence family was 100% racist. They were viewed as unable to think for themselves or come up with and run their campaign themselves.’

Francis describes management using horrifically racist language, referring to Black justice campaigners as ‘monkeys’. He claims HN86 said the Lawrence family were being led by their lawyer Imran Khan KC ‘by the rings through their noses’.

Lawrence was asked whether she recalls any overt racism from the police. She says they may not have used that language to her face, but their dismissive attitude spoke volumes about their beliefs:

‘I think they believe that as a Black you can’t string two sentences together, and that many times I think they believe that Mr Khan had to had to speak on my behalf and tell me what to say, which is so further from the truth.

So I think that they have this opinion of what a Black person is like or what a Black family is like. So that seems to influence the way in which they think about people…

I think the police is always very clever and not able to speak in those terms. But by their actions you can always determine exactly what they’re saying to you… they’re so dismissive of anything that you have to say…

Nobody can ever say I’ve been disrespectful to any officer, all my questioning has always been in a way in which I expect them to have respect for me as I have respect for them. And so that’s always been my way of behaving. But I don’t feel as if I’ve always had that from police officers.’

The police have claimed they had to spy on the Lawrence family to prevent supposedly subversive political groups from manipulating or controlling them. However, it is obvious that Baroness Lawrence was very clear in her own objectives and more than capable of managing her own campaign. The family were not about to be influenced or overrun by anyone else.

PREJUDICE IN THE POLICE RESPONSE

In the aftermath of Stephen’s murder, two Family Liaison Officers (FLO), Linda Holden and Steve Bevan, were assigned to the family. Lawrence feels that they did not do their job.

She explained that at the time she had no real understanding of what FLOs were supposed to do, but she now knows:

‘They should be informing us about how the investigation is going, and we didn’t get that sense at all from them.’

Instead, it seemed they were suspicious of the family and surveilling them. Many people visited the Lawrence home to pay their respects and offer support. The FLOs asked the family for the names of everyone who visited in the days after Stephen’s death.

We were shown witness interviews with both FLOs. Holden explained that names would be taken down and recorded [UCPI000003258]. Bevan described his role as being there to investigate a crime [UCPI000003259]:

‘If anything comes up that, in my experience as a detective, needs to be addressed then it would have been reported back and to hell with the consequences, to be quite honest…

The family had been taken over, had been overtaken by plenty of different factions trying to obviously make a political point.’

It is evident that, from the very start, the police took a political approach to the Lawrence family.

Paul Condon was the Met Commissioner from 1993 to 1999, including the time of Stephen’s murder and the Macpherson public inquiry. In October 2013, he spoke to the Ellison review [UCPI000003255].

Condon went so far as to try and blame the failures of the police on the presence of political campaign groups. He described:

‘a sense that this was very crowded airspace in terms of campaigners. At the time you had, in no particular order, the Anti-Nazi League, the Anti-Racist Alliance, the Socialist Workers Party, you had Militant tendency, you had, I think, something called YRE, which was Youth Against Racism in Europe…

Most of that was incredibly good people trying to do good things; a tiny, tiny, tiny minority really of bad people hell bent on revolution and anarchy.’

POLICE BLAME AN EXCESS OF SUPPORT

Condon said that the police investigation was being inhibited because there were too many civilians supporting the family:

‘It became apparent very early on that this was not a sort of street fight or rival gangs or whatever, this was a nasty vicious murder of an innocent young man, who was brutally killed.

As Commissioner, I had a sense that there was a frustration that they [the police] could not get close to the family to support them. That seemed to be inhibiting the inquiry.’

Lawrence says that isn’t true, the FLOs and the police had plenty of opportunity to talk to the family and to properly investigate the murder:

‘We have, especially myself, tried at every attempt to support the police in their investigation by passing on information that came to us. We did not withhold anything from them. And when the liaison officer came to our house, we would give them those information.

What they didn’t do was to inform us as to what happened to that information that we had passed on. So there was nothing that came back to us. We were the ones that kept giving, giving, giving.

Nothing was reported back to us and to say that others were impeding the investigation, I would say that’s not true…

I think they read into whatever they wanted to read into it. Because if they were really looking to solve Stephen’s murder, they would concentrate on the investigation and the information that they were given. And obviously they weren’t doing that.’

Spycop Peter Francis says he received a list of names derived from the lists made by the FLOs and he was asked to establish whether these people were ‘known to the SDS’, what their political affiliations were, and whether they could pose an issue for public order.

He says the list was stapled in his diary. He would regularly refer to it during the early months of his deployment, which began in September 1993, five months after Stephen was killed.

Lawrence explained that she doesn’t really know who was at her house at that time, she had just lost her son and she was mostly shut up in her room grieving, but she does recall the FLOs asking who all the visitors were. She says that the people who came to her house were there to support them, whereas the FLOs were not asking about Stephen or even about the family.

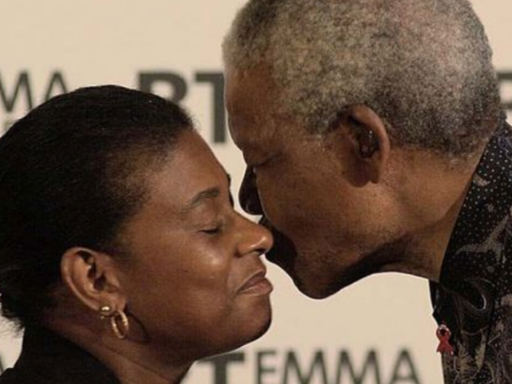

Nelson Mandela greets Doreen Lawrence, 6 May 1993

FLO Bevan said when interviewed that the Anti-Racist Alliance and African National Congress were both present in the house. Doreen has no recollection of the latter ever being there.

However, she did meet the ANC’s Nelson Mandela in London during his visit to the UK. He spoke out after the meeting to say that, while he knew Black lives were cheap in apartheid South Africa, he did not expect it to also be the case in London.

That publicity actually led to some arrests being made for the murder, but prosecutors later dropped the charges.

The family’s lawyer, Imran Khan KC, tried to get answers on behalf of the family about why the police were so interested in whoever was providing support. He was met with a wall of silence.

Many groups organised vigils and demonstrations in the aftermath of Stephen’s death. Lawrence pointed out that she was not concerned with anyone’s political agenda. She wanted the focus to be on Stephen, so they set up the Lawrence family campaign. They had a number of key members, including Khan, and they also had links to trade unions.

They also set up the Stephen Lawrence Charitable Trust in his memory. The Trust initially focused on Jamaica and South Africa, supporting young people who, like Stephen, wanted to be architects.

We saw SDS reports about alleged tensions between some of the political groups that were supporting the Lawrence campaign, for example over whether to hold demonstrations in central or South East London. Lawrence made clear she was not a part of this:

‘I don’t like marches, so I don’t go on marches. I don’t feel that at times that really benefits you in a way.’

She was also still working and bringing up her two surviving children. In any case, she was abroad, burying her son, when the demonstration in question took place. Nevertheless, the family was blamed for the disorder that occurred near the BNP headquarters in Welling, South London on 16 October 1993.

Lawrence was asked what she knew about some of the people who supported her family’s campaign, such as Asad Rehman and the Newham Monitoring Group, Alex Owolade and the Movement for Justice, and groups like the Nation of Islam, the Anti-Nazi League and the Socialist Workers Party.

She says she didn’t really know them, she had heard of some of them but had made clear that she was not about to support the other aspects of their campaigning as she was only interested in justice for Stephen.

In the Inquiry’s morning break, Tom Fowler discussed the hearing with Kate Wilson, author of Disclosure: Unravelling the Spycops Files.

POLICE PROTECT THEMSELVES

From the start, the Lawrence family fought to get justice for Stephen. In 1993, they met Peter Lloyd, Minister of State at the Home Office, and asked him for a public inquiry into the handling of Stephen’s case.

He said they didn’t have the evidence to support an inquiry. Lawrence pointed out that this was because:

‘They did not collect the evidence. And if they did, they did nothing with it…

The struggle that we had to go through, it’s like an everyday thing the police did not want to know. People in authority did not want to know. You know, it’s just another Black boy’s been murdered. You know. So what?

We were constantly being ignored. Even though we raised our concerns, nobody was listening to us.’

In fact, it is not entirely true to say the Lawrence family campaign was being ignored. In private, the police were listening, and they were furious with the family for calling them to account and putting pressure on them.

Deputy Assistant Commissioner David Osland was in charge of the area where the family lived. He wrote of his irritation to Commissioner Paul Condon as early as 8 September 1993:

‘Our patience is wearing thin on 3 Area [south-east London], not only with the Lawrence family and their representatives, but also with self-appointed public and media commentators.’

Osland insisted:

‘I am totally satisfied that the Lawrence family have received a professional, sensitive and sympathetic service from the police’

In autumn 1993, the police commissioned an ‘independent’ review of the case, conducted by Detective Chief Superintendent John Barker (who was an officer in the Met, so hardly independent). He also concluded:

‘The investigation has progressed satisfactorily and all lines of enquiry were correctly pursued.’

He went on to blame the ‘involvement of active politically motivated groups’ for the bad press and public relations the police were suffering around the case.

Lawrence pointed out that if they actually had investigated properly, she would not be here 32 years later, giving evidence to her third public inquiry.

Leaflet for march against racist murders, 12 June 1993

In fact, the family were not even told the conclusions of the Barker review at the time. The Macpherson inquiry described the Barker report as factually incorrect, inadequate, flawed and indefensible.

Lawrence says that with each new inquiry she discovered things about the investigation that the police should have told her before but had not.

In December 1997, Kent police published the result of their investigation into police procedures in the Lawrence investigation. It identified weaknesses, omissions and lost opportunities. Nearly five years after the murder, it was the first time Lawrence had heard that, within 24 hours of Stephen being attacked, someone had walked into a police station to give names but was turned away.

During the first inquest they discovered that Stephen did not really receive first aid at the scene. A qualified first aider came and offered to help but the police didn’t let her. Lawrence recalls this being because they were afraid of ‘a black man’s blood’.

Over and over again we heard how the police failed to keep the family informed about their botched investigation.

SPYCOPS ON THE LAWRENCE CAMPAIGN

SDS spying and reporting on the family began in earnest around 1998, while the Macpherson inquiry was taking place.

The first phase of the inquiry was looking at Stephen’s death and investigation. A second phase examined wider issues of racism in the community, and other justice campaigns.

After the announcement of the Macpherson inquiry, the focus of the Lawrence family campaign shifted to mobilising around it. They were a small group, involved in organised, lawful and public campaigning.

They held regular press conferences, encouraged people to attend the hearings, produced a booklet about what was going on, and linked with other families and organisations to make submissions in the second phase. There was nothing about the campaign that was not either very public or, for very good reason, private as it involved their family life.

The Undercover Policing Inquiry has SDS reports about the Stephen Lawrence campaign set up by the family, the wider Lawrence family support group, and the Stephen Lawrence public inquiry itself. It even has some personal reporting on Doreen and her then husband Neville.

The reports come primarily from HN81 ‘David Hagan’, but also from HN43 Peter Francis and HN15 Mark Jenner. Lawrence says she has seen photographs of the three men but does not recall knowing any of them.

The reports reflect the same racist attitudes we saw in the early days of the police investigation. In January 1998, HN15 Mark Jenner reported [MPS-0000794] that groups like the Anti-Racist Alliance and Movement For Justice supported families like the Lawrences because they aimed to ‘influence the naive from within,’ describing a ‘left-wing scramble for recruitment amongst victim families’.

Spycop HN81 ‘Dave Hagan’ (left) undercover with Movement For Justice. He was ther main spy on the Lawrence campaign.

It’s part of an unyielding narrative in SDS reporting: Black and brown people are gullible and easily manipulated, and left wing groups are trying to take over their campaigns in order to gain political power for themselves.

Lawrence says that if she was naive about anything, it was her expectations of the police and how Stephen’s murder would be investigated. She never felt she was being recruited for anything by political groups.

The undercovers’ reports we saw were about groups trying to prevent racist attacks (something which should have been the job of the police). The tone is derisory, implying that preventing racist attacks is somehow a bandwagon and not a legitimate aim.

Most of the reporting on the Lawrences comes from HN81 ‘Dave Hagan’. His deployment was ironically code-named ‘Windmill Tilter’, a reference to Don Quixote bravely attacking windmills, mistaking them for giants. This suggests that, even at the time, the police were aware that his intelligence was exaggerated and wilfully misinterpreted the groups he targeted.

Hagan mainly infiltrated Movement For Justice (MFJ) which, as the name suggests, campaigned on a range of social injustices. For this they were deemed a subversive threat by the paranoid SDS. Hagan, true to type, continually exaggerated their intentions.

Hagan submitted reports on groups attending the Lawrence inquiry hearings, and his handwritten note on one of them [MPS-0721970] claimed:

‘It was MFJ’s intention to openly or covertly influence the campaign. It was a high profile opportunity to attack the “state”.’

It was quite unnerving to be sat in this Undercover Policing Inquiry hearing, a public inquiry into police wrongdoing, listening to evidence of how the police treat attendance at such public hearings as though it were a subversive or criminal act.

Hagan’s reports, such as one filed on 25 June 1998 [MPS-0001147], note the race and gender of the people attending the Macpherson inquiry hearing.

Lawrence pointed to that report to say that, six years after Stephen died, these so-called police intelligence gatherers had not even bothered to learn how to correctly spell his name, always using a ‘v’ instead of a ‘ph’.

Again, this is a consistent part of spycop reporting, getting the names of the people and groups they spy on wrong. It happens so much that it becomes hard to believe they could be this incompetent, and perhaps instead it’s another way to denigrate those they spied on.

In the hearing’s lunch break, Tom Fowler made two reaction videos. The first was with James and Lauren from Bristol Counterfire:

The second was with John Burke-Monerville whose family camapign for justice is parallel to the Lawrences:

KILLERS TAKE THE STAND

We were shown an extract from the 2018 BBC documentary ‘Stephen: The Murder that Changed a Nation’, which included footage from 29 June 1998, the first day the five men who murdered Stephen attended the inquiry to give evidence. The killers were met with widespread anger from the crowd.

Stephen Lawrence’s killers at the public inquiry, 1998

There is a lot of spycops reporting focused on that day. People were understandably frustrated that these men were still free, and many people wanted to be present in the public gallery for their evidence.

SDS reporting prior to the event [MPS-0001129] describes plans for a demonstration involving people turning their backs on the five killers, and holding two minutes’ silence in memory of Stephen.

The BBC clip played on, showing Commissioner Paul Condon refusing to resign after the Macpherson report was published in 1999. He challenged the finding of institutional racism and refused to accept that his force was racist.

We saw Doreen Lawrence being interviewed at the time, pointing out:

‘for Condon to say it was just a few bad apples… It wasn’t just a few. There were hundreds of them.’

A statement that is as true now, about the events being examined at this current Inquiry and the Metropolitan Police of today, as it was at the end of the 1990s.

Asked if she remembers the events outside the Macpherson inquiry on 29 June 1998, Lawrence pointed out she was inside, so she didn’t witness it. However, it was the arrogant and disrespectful attitude of the five killers as they walked in (which is evident in the video clips) that provoked the crowd.

A key point for this Inquiry, about that day, is that undercover officer HN81 ‘Dave Hagan’ was in the crowd, and he has admitted to taking part in the disorder, joining in with the pushing and shoving.

Lawrence was clearly angered by the SDS attitude to breaking the law:

‘If you are a police officer you should not be engaged in those activities. And yes, he said he was undercover, but why did he feel it was right for him to engage in those activities? You are supposed to uphold the law and there clearly shows that he wasn’t on that day.’

She also pointed out that, given the level of public interest in that hearing, a second public gallery with video link-up should have been installed from the start, which would have made the protests unnecessary.

SUPPORT GROUPS UNDER SUSPICION

Hemingway showed us report after report, mostly filed by Hagan, about groups like the Nation of Islam and the Movement For Justice, their campaigning activities and their relationship with the Lawrence family and the Lawrence campaign.

Lawrence was quite dismissive of these reports:

‘The campaign was just seeking for justice, to get those individuals who murdered my son to be locked away, and that’s the only purpose of what the campaign was there for. What these other groups were there doing, I cannot say.’

In response to questions about whether she disapproved of groups like the Nation of Islam, she pointed out that while she was aware of them, she didn’t have strong opinions, and doesn’t believe anyone else in the family disapproved of them either.

Likewise Movement For Justice:

‘I was not aware of what the Movement For Justice and what their position has been, because it wasn’t anything that I was part of. So I can’t answer anything to do with them.’

She also pointed out that the police focus on these groups was all wrong:

‘To be told how many years later, after Stephen has been killed, that this was going on, it’s just to show the disregard for us as a family and it is more important for them to look into other groups.

We weren’t concerned about other groups. What we were concerned about is how the investigation was being carried out.’

However, the police even treated Lawrence’s indifference to these groups with suspicion. One report [MPS-0001129] included a handler’s speculation:

‘It is not beyond the realms of possibility that the inactivity of the Lawrence family in not supporting the various groups is that they have been spoken to at a senior level and been promised some sort of carrot. (Perhaps a resignation).’

Lawrence responded that she never received any such promise:

‘It was suggested to me about we should ask for the Commissioner to stand down and I felt at the time it wasn’t for me to ask the Commissioner, it is for the Commissioner himself to know his role and for him to step down on his own accord and not for me to suggest to him. That’s how I felt at the time.’

In fact, despite intense public pressure and the long procession of shocking revelations, there were no resignations over the handling of Stephen Lawrence’s murder.

She was asked about the accuracy of SDS speculation in their reporting about the levels of activity in the Lawrence family campaign. Lawrence brought us all sharply back to the reality of what was happening to her at the time and the utter lack of humanity displayed by the police in spying on her family:

‘It weighed heavily on me, trying to manage my life, my children, as well as all this was going on. It’s really difficult, and we shouldn’t have to be put through all of this.

As a family we should not have gone through this. We’ve not had an opportunity to grieve over our son, because we are constantly battling, fighting for something that should be there readily for us.’

Her answers also exposed the inherent sexism in the reporting which described her as ‘less politicised’ than her husband. She pointed out that she was simply unable to attend a lot of meetings because she had to be there for her children. She is angry that the police tried to pit her against her husband:

‘They saw Neville as being more reasonable than I was. Because I was asking intrusive questions, because I wanted to know more than what they were telling us.

And they seemed to feel that I was probably too inquisitive, whatever, I don’t know. But I know they were trying to pit us against each other. So they see Neville as quite being reasonable and me not so.’

PERSONAL INTRUSION

The reporting also touched on her private life. On 24 July 1993, Hagan recorded in an intelligence report [MPS-0001212] that Neville and Doreen Lawrence were separated.

SDS officers and reports have variously claimed that this information came from Suresh Grover (who denies it could have come from him), or that they heard it from Duwayne Brooks.

Interviewed in 2013 for the Ellison review [MPS-0721973], Hagan defended the fact that he reported it on the grounds that:

‘All intelligence is good.’

This incredibly intrusive reporting of Lawrence’s private life is of particular concern to the Inquiry because the information ended up in the press.

Lawrence says she has no idea how the police or the press would have come to know that. She recalls having confidential meetings with the police and then hearing what was said in the media. There were so many leaks to the press, she couldn’t trust anyone.

She also reminded Hemingway that, as well as being spied on by the Metropolitan Police, her family was also targeted by the press in the phone hacking scandal. However, wherever the information that she and her husband were separated came from, she made clear:

‘Our family life is private and should not be in a police report.’

Asked about the allegations that the SDS tried to find information to discredit the family, Lawrence replied:

‘I wasn’t looking for special treatment. Somebody had died. It is your job to investigate that murder. And that’s all I was asking for, nothing else.

And so to spend their time looking to smear and to find things to destroy us as a family. As I say it’s hard to believe that people go to that extreme.’

In the afternoon break at the hearing, Tom discussed the evidence with Heather Mendick:

RACIST SPYING ALL THE WAY TO THE TOP

Once she had finished presenting the SDS intelligence reports about the Lawrence family, Hemingway moved on to examine the attitudes of SDS managers to campaigns for justice, and the Lawrence campaign in particular.

We were shown a management document dated 1 July 1998 about Hagan’s deployment [MPS-0748092], which described him as being ‘in a unique position to report on the “victims” of deaths in police custody’, sneeringly putting the word victims in quotes.

Bob Lambert, 2013. As SDS manager in 1998, he vetoed the suggestion to tell the Lawrence inquiry about the unit’s spying on the family

We also saw a Special Branch note [MPS-0748392] which referred to ‘perceived police corruption and racism’, demonstrating the police attitude that the very real grievances being highlighted by these campaigns didn’t really exist.

Lawrence was asked about the 1997-1998 SDS Annual Report [MPS-0728620], which indicated a shift in focus towards spying on community-based groups in areas like Brixton, groups like the Movement For Justice and their supposed threat to public order.

She says there is nothing that would justify reporting on her and her family. They had done nothing that could give cause for concern for public order.

HN10 Bob Lambert was an SDS undercover officer who gave evidence about his deployment in tranche 2 of the Undercover Policing Inquiry in 2024. After his time undercover ended, he was promoted to running the unit. He became its controller of operations from 1993 to 1998, a few months after Stephen’s murder to the middle of the Macpherson inquiry.

In an interview in 2013 [MPS-0722549], Lambert claimed his spies were actually there to protect the Lawrence family from campaigners.

Lawrence says if that was their aim, why weren’t they communicating that with the family?

‘Those who were doing things against us, they were well protected. And who was there to protect us? You know, there is no one out there to protect the family.

So it goes at the beginning when Stephen was killed, and the fact that we were sort of thrust into the limelight of things happening, there was nobody supporting the family. We were just left exposed, constantly.’

CORRUPT OFFICERS FALL UPWARDS

However, perhaps the most shocking aspect of the spying on the Lawrence family is the fact that the Stephen Lawrence Review Team, the senior police team producing the Commissioner’s submissions to the Macpherson inquiry, were making use of the SDS spies.

Richard Walton from the Review Team met with HN81 ‘Dave Hagan’ in Bob Lambert’s garden on 14 August 1998 to get information about the Lawrence family supporters’ campaign.

Immediately afterwards, Bob Lambert described that meeting as follows [MPS-0728625]:

‘It was a fascinating and valuable exchange of information concerning an issue which, according to RW [Richard Walton], continues to dominate the Commissioner’s agenda on a daily basis.

RW thanked WT [‘Windmill Tilter’, aka HN81 ‘Dave Hagan] for his invaluable reporting on the subject in recent months. An in-depth discussion enabled him to increase his understanding of the Lawrences’ relationship with the various campaigning groups (like MFJ).

This, he said, would be of great value as he continued to prepare a draft submission to the Inquiry on behalf of the Commissioner. MFJ’s future plans were also discussed at some length.

RW explained a lot of the behind the scenes politics involving the Home Office. It emerged that there is great sensitivity around the Lawrence issue with both the Home Secretary and the Prime Minister extremely concerned that the Metropolitan Police could end up with its credibility – in the eyes of London’s black community – completely undermined.’

Lawrence pointed out that the concerns of the Prime Minister and the Home Secretary were well founded:

‘At the end of the day, within the Black community, the police had no credibility in how they police us and how, you know, what’s happened over the years.

So, yes, in fact rather than doing things to make it better, or to make sure [people] within the Black community they feel supported, what they were doing is the complete opposite.’

When the meeting that Lambert brokered between Richard Walton and HN81 ‘Dave Hagan’ was revealed in March 2014, there was major outrage. Not only did the government set up the Undercover Policing Inquiry but Walton, who had risen to be head of Counter-Terrorism Command, was removed from his post.

Seven months later, despite a pending report from the Independent Police Complaints Commission, the Met reinstated him. Less than a week after the damning report was published in January 2016, Walton resigned, thus avoiding misconduct proceedings.

Lambert had retired from the police in 2007 and had two academic posts teaching new generations of police managers and spycops. He resigned from them both just before the Independent Police Complaints Commission report was published. He retains his MBE awarded for services to policing.

KEEPING IT ALL SECRET

Another briefing note from the time of the Macpherson inquiry [MPS-0720946] contains comments from Operation Commander Colin Black to the Detective Superintendent of Special Branch’s S Squad.

He says:

‘SDS is, as usual, well positioned at the focal crisis points of policing in London. I am aware that Detective Inspector Richard Walton of CO24 [the Met’s race and violent crime task force] receives ad hoc off-the-record briefings from the SDS.

I have reiterated to him that it is essential that the knowledge of the operation goes no further. I would not wish him to receive anything on paper.

I have established a correspondence route to Deputy Assistant Commissioner Grieve via Detective Sergeant McDowell, formerly of SO12, and opened an SP file for copy correspondence with CO24.

It will, of course, fall to C Squad to provide the bulk of that material. They will undoubtedly consult SDS as appropriate.’

It is evident that SDS reporting on the Lawrence campaign was going to the very top of the Met at the time, and that they planned to keep spying on the family and their supporters for quite some time. This is a long way indeed from the police’s claim that it was just a bit of incidental reporting because of other groups that supported the campaign.

It’s also clear that the senior officers knew at the time that it was wrong, as evidenced by requests for the operation to be kept secret and nothing to be put in writing.

Asked how she feels about this, Lawrence almost seemed to deliberately misinterpret the question:

‘It seems as if all during Stephen’s case that senior officers had been informed or continued to be informed about Stephen’s case, but none of that was ever communicated to us. No information was shared to us for us to understand how they are working.

And to say whether or not there was anything to come out of the work that they are doing… Were they looking to arrest any of these individuals?’

She reminded Hemingway that she was never even kept informed by the police about how the murder investigation into her son’s death was going, so she certainly never knew anything about the rest of their activities.

She then cut to the heart of the matter:

‘It just seems as if they are just trying to cover themselves, protect themselves from criticism.’

Had the police put as much resources and attention into this case when Stephen was murdered as they did into spying on the family at this late stage, they would have caught the killers.

Worse, had the police put the resources in finding the gang the first time they attacked someone, they wouldn’t have been still on the street and able to kill Stephen.

STILL AVOIDING THE TRUTH

At the end of her evidence, Lawrence was re-examined by her own counsel, Imran Khan KC, who has been with her since the very beginning of her campaign. There was a marked difference between Hemingway’s persistent queries about disorderly intent and Khan’s connection with the outrageous truths of the issue.

His questions gave a mother, very clearly still grieving her murdered son, an opportunity to tell the Met Police how she really felt.

She pointed out that the police knew who was carrying out racist attacks in the area at the time:

‘Those individuals were known to the police before Stephen’s murder… and the local people within the area knew of them and were giving as much information as they could to the police. And the mere fact that they did nothing with those information.

Q. Would it be fair to say that had they put resources into looking at the previous murders and the racism in the area, do you think that might have made any difference to Stephen and what happened to him?

A. Definitely… if that had been a Black family who the police knew about, they would leave no stone unturned in either to arrest them and to make sure that those individuals were brought to justice.

But when it comes to a Black individual that has been murdered by whites, it’s as if they don’t care. His death is meaningless and that’s why I was just so adamant in making sure that Stephen’s name is never forgotten, because he did nothing wrong.’

She expressed her anger at Sir Paul Condon, who knew all about the police failures and the spying. He entered the House of Lords before she did and she says he cannot even look at her when she is there:

‘He’s never approached me. And even if he walked past in the corridor, he would just hold his head straight, he would never communicate with me.’

Khan asked her about her meetings with successive Home Secretaries. Michael Howard was Home Secretary from the time Stephen was murdered until just before the Macpherson inquiry was announced four years later. He did not meet with her.

But in 2014, just after the Undercover Policing Inquiry was announced, he requested an urgent meeting in which he eagerly assured her that he had known nothing about the spying.

‘He’s the one who invited me to a meeting and he was quite keen to express that he knew nothing about the undercover policing that was happening around my family…

But I don’t believe anything that he was saying, because I think as a Home Secretary, between the Commissioner, so they report to each other, they have conversations, so he would have known about what was happening. I don’t believe that he didn’t know.’

He is now Lord Howard, and Lawrence notes that, like Paul Condon, he studiously ignores her in the House of Lords:

‘We pass each other in the corridor and he’s never spoken to me. So that was the very first time, when he invited me to a meeting. And since then, he hasn’t spoken to me again.’

Her message to the Home Office was this:

‘I would say that the Home Secretary, whoever they are, they have a duty of care. You know, they are there to – especially around the police – there to protect society. And I am part of that society. And none of that took place for us.’

She said the Home Office needs to come and give evidence and explanations to this Inquiry.

She pointed out that, despite it all, she is there giving evidence:

‘It’s something that I am obliged to do. And I think if I was to turn around and say, “I don’t want to be here”, I am sure there would be eyebrows raised saying I have been very critical but yet I am not here in person to give evidence. I don’t like being in the spotlight, I really don’t like it.’

And she had a very clear message for the SDS officers accused of racism and spying on her family, HN86 and HN81 ‘Dave Hagan’, who are both refusing to come to the Inquiry:

‘The least you can do, and have that respect, is to come and give your evidence in public.’

TRUTH MUST ACCOMPANY APOLOGIES

Lawrence spoke about institutional racism, an issue she has worked on for many years and clearly understands deeply. She made clear that the failure to investigate Stephen’s murder was driven by institutional racism, a fact firmly supported by the findings of the Macpherson inquiry.

‘Stephen was a Black young man and in their eyes he must be a criminal. He must be up to something. He cannot be innocent.

And so they set about in whatever they are doing is to undermine we, as individuals, that we do have feelings…

I thought they would be so disgusted in how Stephen was murdered that they would want to do all that they could to bring his killers to justice. And the reality is no, they weren’t interested.’

She also made clear that the attitudes of the SDS in assuming she was being led by others, or that she was not particularly intelligent, or that they were seeking to protect her so they put resources into the undercover operations, were all driven by institutional racism as well:

‘I find it quite insulting really, for them to think that I couldn’t string two sentences together, and also the fact that they needed to protect me.

Yes, they needed to protect me, because I am part of society. They needed to protect my son, which they didn’t do…

It is what followed that, that their intent was completely different.’

Lawrence received an apology from the Met Commissioner Bernard Hogan-Howe on 27 March 2014 for the spying on the family.

Deputy Assistant Commissioner John Saville attended this Inquiry in person on the day she gave her evidence, to apologise to her again. He apologised in private, but Lawrence spoke publicly to him from the witness box:

‘I would welcome the apologies, because I think I have had so many over the years, you know, when is an apology going to be where I feel satisfied that they understand what has happened, and it has taken 32 years for us to get to this point…

It’s like when things become in the public domain, they feel that they need to apologise, that’s the thing…

Whatever happens out of this Inquiry, this now, is for the truth to be heard and to be published…

So I would like, at the end of this, is the report should be shown that what had happened to us was so wrong; and not just apologies just for the sake of apology, it must be meant that way.’

Doreen Lawrence ended her evidence by talking about her son Stephen:

‘Stephen was a decent young man. He like most young people growing up, you know, cheeky, has his faults about him. But at the end of the day he was respectful. He was respectful. He would never have gone out of his way to hurt anyone… nobody had a bad word to say about him. Nobody.

And the mere fact that his life was taken and to have these people who are supposed to be there to protect him and look after and to make sure that whatever happened to him, they did nothing…

For the past 32 years I haven’t had opportunity to grieve my son properly because I have to challenge every step of the way what has happened to him…

Your skin colour should have nothing to do with it. When somebody has done something wrong, they need to be punished. Stephen did nothing wrong, but we have been punished for the past 32 years.’

The Inquiry’s Chair, Sir John Mitting, thanked Doreen Lawrence at the end, not only as a judge, but as a father:

‘I am the father of three sons. I would understand if something had happened to them of the kind which has happened to yours. Thank you for putting yourself through what I know has been a difficult experience and giving evidence to me. Thank you.’

It was an astonishing admission that he’d missed the whole point. Doreen Lawrence wasn’t here because her son died. Rather, it was because of a vast range of racist actions, from the murder itself, through the decades of police reponses to the failure of official procedures and state agencies. These things would never happen to a white family, let alone one where the dad is a knighted judge.

Mitting’s family cannot and will not ever experience what Lawrence has been through. It’s only possible to portray it as the simple loss of a son if you haven’t understood anything about the institutional racism that you’ve just spent the day having laid bare in front of you.

After the hearing ended, Tom Fowelr and Kate Wilson reflected on it: