UCPI Daily Report, 14 October 2024

Tranche 2, Phase 2, Day 1

14 October 2024

The first day of the new round of Undercover Policing Inquiry hearings, setting out what to expect in the next three months.

The first day of the new round of Undercover Policing Inquiry hearings, setting out what to expect in the next three months.

CONTENTS

Introduction

Provisional timetable of upcoming live evidence

David Barr KC (Counsel to the Inquiry)

Peter Skelton KC (Commissioner of Police for the Metropolis)

Oliver Sanders KC (Designated Lawyer’s Core Participant Group, HN122; HN1; HN32; HN69; HN39; HN109)

Neil Sheldon KC (Home Office)

Quincy Whitaker (John Burke-Monerville)

Rajiv Menon KC (Richard, Nathan and Audrey Adams)

Charlotte Kilroy KC (The Category H Core Participants)

James Scobie KC (Michael Chant, Lindsey German, Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament)

Introduction

The Undercover Policing Inquiry held its ‘Tranche 2 Phase 1’ hearings in the summer of 2024. ‘Phase 2’ has just begun, two weeks later than scheduled, and these hearings are due to continue until 23rd January 2025. There are 39 days when hearings will be held. The Inquiry has scheduled some breaks.

The majority of witnesses will be civilians who were spied on by undercover officers from the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS), but we are due to hear evidence from at least four of the undercovers, and five officers who worked in the unit’s back office (four of them senior managers).

This round of hearings kicked off on Monday 14th October 2024. Opening Statements were delivered online over Days 1 and 2.

Provisional timetable of upcoming live evidence

Please note that this timetable is a provisional one and may well change over the coming weeks; it’s already been altered a few times. Check the Inquiry’s website to be sure!

Click on each hearing’s title for more detailed information and timings for each day.

Day 3 (Mon 21 October)

• 2:00 PM: ZWB

Day 4 (Tue 22 October)

• 10:00 AM: Kaden Blake

Day 5 (Wed 23 October)

• 10:00 AM: HN122 ‘Neil Richardson’

Day 6 (Thu 24 October)

• 10:00 AM: Richard Adams

• 2:00 PM: John Burke-Monerville

The Inquiry takes a break for the week commencing Monday 28 October

Day 7 (Mon 4 November)

• 2:00 PM: Martyn Lowe

Day 8 (Tue 5 November)

• 10:00 AM: Dave Morris

Day 9 (Wed 6 November)

• 10:00 AM: Chris Baillee

Day 10 (Thur 7 November)

• 11:00 PM: Gabrielle Bosley

Day 11 (Mon 11 November)

• 10:00 AM: Timothy Greene

• 2:00 PM: Albert Beale

Day 12 (Tue 12 November)

• 10:00 AM: Robin Lane

Day 13 (Wed 13 November)

• 10:00 AM: Paul Gravett

Day 14 (Thu 14 November)

• 10:00 AM: Paul Gravett

• 2:00 PM: Geoff Sheppard

Day 15 (Fri 15 November)

• 10:00 AM: Geoff Sheppard

The Inquiry takes another break during the week commencing Monday 18 November

Day 16 (Tue 26 November)

• 10:00 AM: Belinda Harvey

Day 17 (Wed 27 November)

• 10:00 AM: Helen Steel

Day 18 (Thu 28 November)

• 10:00 AM: ‘Jacqui’

Day 19 (Mon 2 December)

• 10:00 AM: HN10 ‘Bob Robinson’ Bob Lambert

Day 20 (Tue 3 December)

• 10:00 AM: HN10 Robert Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’

Day 21 (Wed 4 December)

• 10:00 AM: HN10 Robert Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’

Day 22 (Thu 5 December)

• 10:00 AM: HN10 Robert Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’

Day 23 (Mon 9 December)

• 10:00 AM: ‘Callum’

• 2:00 PM: ‘Walter’

Day 24 (Tue 10 December)

• 10:00 AM: AFJ

Day 25 (Wed 11 December)

• 10:00 AM: Clare Hildreth

Day 26 (Thu 12 December)

• 10:00 AM: ‘Jessica’

Day 27 (Wed 18 December)

• 10:00 AM: HN2 Andrew Coles ‘Andy Davey’

Day 28 (Thu 19 December)

• 10:00 AM: HN2 Andrew Coles ‘Andy Davey’

Day 29 (Fri 20 December)

• 10:00 AM: HN2 Andrew Coles ‘Andy Davey’

The Inquiry takes a break for the two weeks commencing Monday 23 & 30 December

Day 28 (Mon 6 January 2025)

• 10:00 AM: Denise Fuller

Day 29 (Tue 7 January)

• 10:00 AM: HN1 ‘Matt Rayner’

Day 30 (Wed 8 January)

• 10:00 AM: HN1 ‘Matt Rayner’

Day 31 (Thu 9 January)

• 10:00 AM: HN1 ‘Matt Rayner’

Day 32 (Mon 13 January)

• 10:00 AM: HN115 DCI Tony Waite

Day 33 (Tue 14 January)

• 10:00 AM: HN115 DCI Tony Waite

Day 34 (Wed 15 January)

• 10:00 AM: HN69 DCI Malcolm MacLeod

Day 35 (Thu 16 January)

• 10:00 AM: HN32 DS Michael Couch

Day 36 (Mon 20 January)

• 10:00 AM: HN39 DCI Eric Docker

Day 37 (Tue 21 January)

• 10:00 AM: HN39 DCI Eric Docker

Day 38 (Wed 22 January)

• 10:00 AM: HN109

Day 39 (Thu 23 January)

• 10:00 AM: HN109

Opening Statements: Day 1

1) David Barr KC (Counsel to the Inquiry)

David Barr KC

David Barr KC is the Counsel to the Inquiry (CTI), and his written Opening Statement outlines the position of the Undercover Policing Inquiry.

He was the first to address this set of hearings, known as Tranche 2, Phase 2 (T2P2).

Although Mitting and Barr were clearly in the hearing room, Core Participants who showed up were not allowed in and public access to the opening statements was ‘online only’. This was a cruel decision.

CTI’s statement included multiple accounts of predatory undercover officers lying about their ages in order to target and groom very young and vulnerable women. He described ‘cold, calculating emotional and sexual exploitation’, while the victims of these and other officers were denied the opportunity to be together at the Inquiry venue. Instead they were left isolated, listening to disturbing revelations at home.

Barr explained that T2P2 will examine the deployments of 7 ‘open’ former Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) officers (for whom at least the cover names have been made public), 11 ‘closed’ officers (whose real and cover names have been withheld, and who will give evidence in secret) and 14 former SDS managers. It will look at the infiltration of activist groups from 1983-1996. 26 members of the public have made statements and 22 will give oral evidence.

The Inquiry’s work in this period will include:

‘Whether the undercover deployments in question were capable of justification, the sexual deceit of women (both admitted and alleged), reporting on black justice campaigns, the alleged participation of undercover police officers in serious offending, potential miscarriages of justice, failure to declare the involvement of undercover officers to prosecutors or courts, violation of legal professional privilege, alleged participation in torts, the influence of UCOs within groups, the continuing use of deceased children’s identities and officer welfare will be key aspects of our investigation in this phase.

‘So too will the knowledge, attitude, actions, or inactions of managers within the SDS in relation to these and other issues. Standing back from specific events, the culture of the unit will remain an important overarching theme.’

The language Barr used is interesting. The Inquiry will investigate whether these undercover deployments were ‘capable of justification’, not whether or not they were justified. It may already be clear to Counsel to the Inquiry that the actual conduct of the unit cannot be justified. Any assessment of justification must therefore be hypothetical, ignoring the facts of the operations.

It is also encouraging that he appears to have kept the role of managers and the culture of the unit in his sights.

He focused his statement primarily on the 7 ‘open’ officers:

• HN11 Mike Chitty ‘Mike Blake’ – deployed April 1983-June 1987 into the animal rights movement in South London. Chitty will not give evidence. The Inquiry believes he lives abroad. However, interviews he gave to ‘Operation Herne’ will be published.

• HN10 Robert Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’ – infiltrated London Greenpeace, in North

London, and other groups between 1984 and 1989. CTI states ‘his ultimate target was the Animal Liberation Front.’ Lambert will give live evidence from 2-5 December.

• HN87 ‘John Lipscomb’ – successor to Chitty, who infiltrated the animal rights movement in South London between 1987 and 1990, first in Bromley then Brixton. His reporting focused on hunt saboteurs. He provided a witness statement but ‘Lipscomb’ is considered too ill to give evidence.

• HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’ – infiltrated anarchist groups, including London Greenpeace, 1987 -1991, overlapping with and replacing Lambert. He has made witness statements, but Dines is refusing to give oral evidence. He lives abroad.

• HN122 ‘Neil Richardson’ – infiltrated the West London Branch of the Revolutionary Communist Party and then Class War, 1989 – 1993. ‘Richardson’ will give oral evidence on 23 October.

• HN2 Andrew Coles ‘Andy Davey’ – infiltrated a number of animal rights groups in South London between 1991 and 1995. Coles will give oral evidence from 18-20 December.

• HN1 ‘Matt Rayner’ – infiltrated animal rights groups 1992-1996, including London Boots Action Group, London Animal Action, and the West London hunt saboteurs. Based in north-west London, he reported on activists as far afield as Liverpool and Manchester. ‘Rayner’ will give live evidence from 7-9 January 2025.

Barr addressed a number of themes:

Sexual Relationships

This was perhaps the strongest yet from Barr on sexual relationships the officers had. He addressed the relationships each officer had:

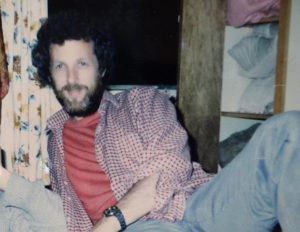

Spycop HN11 Mike Chitty ‘Mike Blake’ undercover in the 1980s

On his own admission, Chitty entered into sexual activity with female activists whilst he was undercover. This included a relationship with the woman known to the Inquiry as ‘Lizzie’.

He remained in contact with members of his target group, including ‘Lizzie’, after his deployment had ended, and this was eventually discovered. There is evidence that Detective Sergeant Chitty went so far as to propose marriage to ‘Lizzie’.

Lambert admits to having sexual relationships with at least 4 women while undercover between 1984-1989, including fathering a child with an activist known as ‘Jacqui’. Lambert has told the Inquiry that he informed his manager (DI Barber) of this pregnancy in the pub. Barber allegedly decided not to report it and left Lambert ‘to deal with the situation’. (‘Jacqui’ will give evidence on 28 November)

Lambert went on to have a nearly 2-year relationship with Belinda Harvey starting in 1987. Harvey states Lambert ‘often professed his love for her, expressed a desire to have children with her and had planned with her to settle down in a home of their own.’ She describes being ‘deeply troubled’ when Lambert suddenly claimed he had to flee the country. (Belinda Harvey will give evidence on 26 November).

Dines admits to a sexual relationship with activist Helen Steel while undercover from 1990-1992. Dines claims in his statement that he used Steel ‘to maintain his cover and obtain intelligence.’ Barr pulled no punches, describing Dines’s behaviour as ‘cold, calculating emotional and sexual exploitation.’ (Helen Steel will give evidence on 27 November).

‘Lipscomb’ admits to multiple instances of sexual activity with female activists, including ‘sexual fumbling’ while sharing beds in activist squats.

Coles is accused of having had a sexual relationship with a 19-year-old activist known as ‘Jessica’ in 1992, when he was actually 32 and married. Barr noted that Coles denies this. However his statement went on to give detailed accounts of how he initiated sexual contact and a relationship with ‘Jessica’. (‘Jessica’ will give evidence on 12 December)

Barr mentioned other women who recall unpleasant incidents where Coles ‘lunged’ at them, and chased them around. Fellow officer ‘Matt Rayner’ also confirmed in an interview that a woman he spoke to at the time described Coles as ‘creepy’ in his undercover persona:

‘it felt like she described him with a shudder.’

‘Rayner’ admits to a sexual relationship with activist Denise Fuller from 1993-1995. He describes his feelings as ‘genuine’ despite being married in his real identity. However Fuller draws attention to his contemporary intelligence reports about her which suggest his claims of ‘genuine feelings’ are a lie. (Denise Fuller will give evidence on 6 Jan 2025)

Management knowledge of sexual relationships

A key issue is the extent to which SDS managers knew about and condoned these relationships. Several officers claim managers must have been aware. DS Chitty is recorded as telling ‘Operation Herne’ that Lambert bragged about fathering a child through a relationship whilst deployed. Lambert states he believes managers knew about his relationships with both ‘Jacqui’ and Belinda.

Dines explains in his statement that ‘he believes that his managers knew about his sexual relationship with Steel.’

HN1 ‘Matt Rayner’ states relationships:

‘were seen as a grey area – they were not advised or encouraged… but they were not prohibited either. This understanding was reinforced by the fact that my managers were aware of [my] situation and did not tell me to stop.’

‘Rayner’ had quite a lot to say about back-room knowledge of sexual relationships. Barr explained:

‘Rayner’ also overlapped with officers whose deployments will be considered in Tranche 3. HN26 ‘Christine Green’ [was] deployed at the same time as ‘Rayner’ into animal rights circles… ‘Rayner’ states that he knew of her ‘friendship’ with an activist ‘and assumed it was sexual… The office would have known’.

‘Rayner’ further recalls that HN14 Jim Boyling ‘Jim Sutton’ made reference to being in a relationship whilst deployed and acknowledges that he also knew that HN15 Mark Jenner ‘Mark Cassidy’ was having a sexual relationship whilst deployed.

‘Rayner’ later acted as mentor to HN16 James Thomson ‘James Straven / Kevin Crossland’, another officer who went on to form intimate relationships in his undercover identity, albeit ‘Rayner’ denies knowing about them.’

Barr’s account here is quite striking, giving one of the clearest impressions to date of how prevalent sexual relationships were within the SDS, and how generalised and widespread knowledge about them must have been within the unit.

Barr made it very clear that there will be no consideration in this Inquiry of whether these relationships could have been justified:

‘We shall need to examine the utility of the deployment in order to help answer the question whether it was capable of justification. That does not mean that we will be examining whether sexual deception was justified. It was not.’

Identity theft

The grave of Mark Robert Robinson whose identity was stolen by spycop Bob Lambert

‘Bob Robinson’ (Lambert) and ‘John Barker’ (Dines) were cover names stolen from the identities of deceased children.

The cover name ‘Neil Richardson’ (HN122) was derived in part from the life story of Neil Robin Martin who died aged 6.

Neil’s mother, Faith Mason, has provided a powerful witness statement which tells his story and describes the impact on her and her family of learning his identity had been used in this way. There is evidence that HN122 traveled to the area where Neil’s family lived.

Coles used the first name and date of birth of a deceased child and added the surname ‘Davey’, to form his cover name ‘Andy Davey’.

HN1 used the identity of Matthew Edward Rayner, who died of leukemia at the age of 4. Matthew’s brother has provided written evidence to the Inquiry and his older sister, Kaden Blake, will give evidence about her brother and the impact the use of his identity has had on the family. (Kaden Blake will give live evidence on 22 October)

Officers committed serious crimes

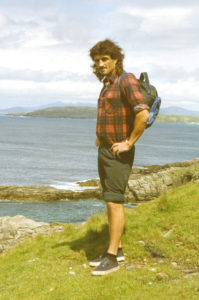

Spycop HN2 Andy Coles ‘Andy Davey’ (2nd from left) on a peace march at RAF Fairford, 1991

A major issue to be examined during this Tranche will be about undercover officers who incited or participated in serious crime.

Andy Coles claims he participated in animal liberations and other criminal activity to maintain his cover.

‘Matt Rayner’ is accused by Geoff Sheppard of encouraging him to use a firearm to shoot a vivisector and offering to act as driver.

Bob Lambert is accused of perpetrating an arson attack on a director’s home and writing leaflets inciting criminal acts.

Witness Chris Baillie alleges that Bob Lambert drove him to a butcher’s shop where another activist threw a brick through the window. Baillie was then arrested and convicted, while Lambert was not. (It is expected live evidence about these allegations will emerge throughout the T2 evidence hearings).

Most significantly, Lambert is accused of planting an incendiary device at the Debenham’s store in Harrow on the night of 11 July 1987. Barr noted that DS Chitty is recorded as telling ‘Operation Herne’ that he believed that DS Bob Lambert had led the cell which attacked Debenham’s stores. Core Participant Paul Gravett accuses Lambert of being

‘involved from the start and of being the person who attacked the Harrow branch.’

Geoff Sheppard also states:

‘Lambert was deeply involved and committed the attack in Harrow.’

Helen Steel and Belinda Harvey provide corroborating accounts of Lambert’s alleged involvement. Lambert claims he had no advance knowledge of the action. However, the convictions of Andrew Clarke and Geoff Sheppard for the attacks are currently under appeal ‘based upon DS Lambert’s alleged actions and undisclosed role.’

(Paul Gravett will give evidence on 13 and 14 November and Geoff Sheppard will give evidence on 14 and 15 November)

Undermining the justice system

Spycop HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’ while undercover

Barr cited multiple instances where officers were arrested or appeared in court using their false identities, without disclosing their true identity or status to the court.

Lambert was arrested and bound over in court for a protest at a meat market in 1985. Documents show a senior police officer was informed of Lambert’s true identity but there is no record of the court being informed.

Dines was arrested at the Poll Tax riot in 1990 and charged under a false name. Managers directed him to fail to appear in court and ‘cancel all records’, suggesting contact with the court or prosecution.

HN1 ‘Matt Rayner’ recalls giving evidence in court as a defence witness for two activists, without disclosing his true identity to the court. His manager Bob Lambert commented he had ‘behaved in a thoroughly professional manner throughout.’

Coles was arrested and charged under a false name at a hunt saboteur demonstration in 1994. His managers instructed him not to appear in court.

Barr noted that:

‘The Inquiry will explore further with SDS managers in tranche 3 [hearings next year examining 1993-2008] what this reveals about their attitude to the criminal justice system.’

He describes the hierarchy of SDS interests:

‘the first and primary interest being to ensure that deployments were not interrupted by overt involvement in the criminal justice system, even if that meant providing a false name to a court, and/or failing to provide significant information to the prosecution or a court (vis. that a defence witness was in fact a police officer).’

There are also concerning allegations about officers’ reporting and conduct towards Black justice campaigns.

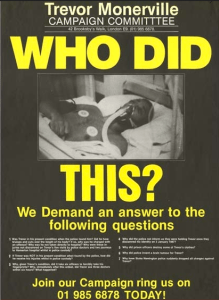

The Rolan Adams Family Campaign and Trevor Monerville Defence Campaign, both involved Black teenagers who died in racist attacks. Rather than properly investigating these murders, the SDS sent officers to report on the justice campaigns.

The Security Service

The Inquiry is also investigating the SDS’s relationship with the Security Service (MI5). Alongside CTI’s Opening Statement, the Inquiry also published the written statement by someone known only as ‘Witness Y’, on behalf of MI5.

Barr described how the Security Service’s assessment of subversion as a threat declined significantly during the T2 period.

Witness Y explains the Security Service ‘scaled back’ counter-subversion work in three steps in 1988, 1992 and 1996. By 1996, subversion was assessed as a ‘low to negligible level’ threat.

Despite this, undercover deployments into activist groups continued throughout this period. Documents show regular discussions about targeting took place between the two agencies.

A 1989 Security Service briefing described the SDS as ‘sympathetic and responsive to the needs of the Service,’ and stated it was ‘extremely important that everything possible’ be done to maintain SDS coverage of certain groups.

Justification

As noted above, despite recognising that aspects of police behaviour could never be justified, the Inquiry does intend to investigate whether the targeting and infiltration of these activist groups was ‘capable of justification’.

However, Barr noted that several officers’ statements cast doubt on whether the groups posed a serious threat.

HN87 ‘John Lipscomb’ states in his witness statement that he ‘doubted the utility of his reporting’ on animal rights activists.

HN122 opined at the end of his deployment that ‘the threat to national security from CWO and CWF was very low.’

Barr said:

‘the question that arises is… whether he should not have been deployed into these groups at all?’

An SDS report authored by HN1 ‘Matt Rayner’ in 1996 asserted there were only ‘about 20’ committed Animal Liberation Front extremists in the UK and stated ‘the overt groups such as LAA [London Animal Action] are only of passing public order interest, not significant in its own right.’

In all, there was a sense in Barr’s delivery that he gave rather short shrift to the police interpretation that these deployments were justifiable. He ended a long list of misconduct allegations in Lambert’s deployment with the observation that:

‘Lambert’s deployment was regarded as an outstanding success by his managers such that he was awarded a Commissioner’s Commendation.’

However, whether the deep irony of that comment was intended is difficult to assess. Barr’s delivery is always very dry; and what the Chair of the Inquiry’s view will be of the justification or not of these blighted operations remains to be seen.

More evidence uploaded

Barr also mentioned several hundred new pieces of evidence being uploaded onto the Inquiry website.

These include correspondence between the United States Air Force and the Ministry of Defence in 1983, on the subject of ongoing protests at RAF Upper Heyford and the potential ‘political repercussions’ if an American serviceman were to shoot a British peace protester on the base.

Another item is a report which lawyers acting for the ‘Category H’ (individuals in relationships with undercover officers) victims had recommended for Mitting’s reading list back in Tranche 1, and the lawyer acting for the Met referred to in the last set of hearings.

Entitled ‘The police in action’, this is a detailed study carried out by academic researchers and published by the Policy Studies Institute in 1983. It describes the pervasive sexism and racism found in the force.

2) Peter Skelton KC

Peter Skelton KC

Next we heard Peter Skelton KC deliver an Opening Statement on behalf of the ‘Commissioner of Police for the Metropolis’, ie the Metropolitan Police as an institution.

A longer, written, Statement is available on the website; this was a much shorter, oral, submission.

Skelton only spoke for around 15 minutes, but used much of this time to apologise on behalf of the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) to various Non State Core Participants.

Apology number 1

He began by thanking two more families for speaking about the distress they had suffered after making the shocking discovery that spycops had stolen the identities of their loved ones.

The Met apologised to Francis Bennett and Honor Robson for the theft of their brother Michael Anthony Hartley’s identity by HN12, and to Marva Lewis and Judy Lewis for the theft of their brother Anthony Lewis’ identity by HN78. There were assurances that this sick practice is no longer being used to create cover identities, and ‘will never be used again’.

Apology number 2

There were also apologies for ‘Bea’ and ‘Jenny’, two women who gave ‘moving accounts’ of the impact of discovering they had been deceived into sexual relationships by HN78 Trevor Morris during Phase 1.

According to Skelton, the Met was ‘profoundly disappointed’ by his failure to ‘take responsibility for his actions and to apologise for the hurt he has caused them’.

Apology number 3

Finally, apologies were made to two Black families whose justice campaigns were spied on: the families of Rolan Adams and Trevor Monerville. The Met now say that they were spied on due to undercovers ‘following their existing targets into them’, but admit that this reporting should have stopped earlier and the information gathered should not have been retained.

Smearing the animal rights movement

Apologies over, Skelton went on to talk about the police’s justification for infiltrating animal rights groups. He spoke of a growth in ‘militant’ animal rights activism during the 1980s and ‘90s, describing direct action as ‘serious crime’.

He name-dropped groups such as the Animal Liberation Front (ALF) and Animal Rights Militia (ARM), and suggested that these ‘attacks’ were ‘violent’, ‘prevalent’ and ‘widespread’, claiming this justified the deployment of long-term undercovers in the animal rights movement.

However, he went on to acknowledge that these deployments were marred by officer misconduct, particularly regarding deceitful sexual relationships. Every single officer sent in to the animal rights movement during this period (1983-1992) engaged in sexual activity while undercover.

Apology number 4

The first was HN10 Bob Lambert, whose deployment lasted over 4 years. During this time, he had relationships with at least four women, fathering a child with one of them. The Met now also apologised to that child, now a man known as ‘TBS’, for the distress he has suffered

Details were given of the other officers:

- HN11 Mike Chitty, who had a sexual relationship with ‘Lizzie’ between 1985-87, and has admitted other ‘sexual impropriety’

- HN87 ‘John Lipscomb’ admitted to sexual activity with at least four women

- HN5 John Dines had a serious long-term relationship with Helen Steel

- HN2 Andy Coles had a relationship with ‘Jessica’

- HN1 ‘Matt Rayner’ had a relationship with Denise Fuller.

Apology number 5

Spycop HN10 Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’ holds his newborn son TBS, September 1985

Skelton reaffirmed that the Met ‘unreservedly apologises’ for these relationships, and the ‘widespread culture of sexism and misogyny’ they represent. Again, there is disappointment about the failure of some of these officers to provide oral evidence and/or witness statements to this Inquiry.

According to the police, and contradicting the level of ignorance claimed by previous witnesses, SDS managers knew, or should have known, about these relationships. There should have been ‘vigilance, critical enquiry, explicit prohibition and training’ but there wasn’t.

More management failures

The Met’s statement details a number of instances of undercovers being arrested, and sometimes charged and taken to court in their false identities.

They now admit that proper disclosure should have been made, to investigators as well as prosecutors and courts, and that miscarriages of justice are the inevitable result of their failure to do so. The unit’s managers failed in their duties and responsibilities, to protect fair trials and not allow courts to be misled.

Skelton also made some comments about the welfare of undercover officers, pointing out that the SDS managers could have been more proactive about intervening to offer them support (perhaps with trained psychologists). He stated that each manager had their own unique style of management, meriting individual examination, but admitted that there were ‘systemic management failings’ that the Met could take corporate responsibility for.

One of these was a failure to intervene when it came to the ‘overall tone and content’ of reporting. Another was what seems to have been an ‘aversion to discipling wrongdoing’, which, coupled with commendations and praise for Lambert, contributed to a growing culture of impunity for increasingly serious misconduct.

Justification

Before ending, Skelton reiterated that the animal rights movement was viewed as ‘subversive’ and dangerous, and the covert infiltration of these groups was therefore necessary. He suggested that any final assessment of the justification and value of these deployments, and the reports they generated, could only be done by consulting the ‘wider intelligence community’, and mentioned the statement from ‘Witness Y’.

3) Oliver Sanders KC

Oliver Sanders KC

Our final speaker in the morning session was Oliver Sanders KC, who represents the ‘Designated Lawyers’ group of former officers.

These are two undercover officers, whose real names are being kept secret: HN1 ‘Matt Rayner’ and HN122 ‘Neil Richardson’.

The rest worked behind the scenes. These were HN32 DS Michael Couch, and three managers: HN39 Michael Docker, HN69 (Malcolm MacLeod), and HN109 (whose real name we don’t know).

Again, there is a much longer written Opening Statement but this was quite a short speech.

Whinging about the Inquiry itself

Sanders began by complaining on behalf of his clients about the Inquiry and how it was being conducted.

To the amazement and disgust of listeners, who reacted furiously on social media, he ended up spending approximately half of his time on this topic. He claimed that the Inquiry was now a ‘two tier process’, and that former officers were being maltreated, ‘belittled and sneered at simply because they served as police officers in a different era’.

They felt that they were being subjected to ‘heavy adversarial challenge’ (translation: they were asked questions, by David Barr on behalf of the Inquiry – unlike most public inquiries, the Non State Core Participants in this one are not being allowed to ask questions, either themselves or via their own lawyers).

In comparison, they thought that ‘civilian witnesses’ (i.e. those they spied on) were being allowed to share their experiences without being challenged at all (which viewers of the Tranche 1 hearings will know is not true).

He complained about the length of time each hearing took, and about the fact that some of the recent hearings in the summer went on past 6pm (going so far as to produce a table in the written document detailing exactly how many minutes each witness spent giving evidence).

Spycop HN10 Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’ handing out the McLibel leaflet he co-wrote, McDonald’s Oxford St, London, 1986

He pointed out that many of the officers are now in their 70s and so a long day is tiring for them – obviously many of those they spied on are also getting older now, as is Mitting himself! – and was anxious to tell us how they had ‘voluntarily given up their time’ to provide witness statements.

Many of the Non State Core Participants have still not received any disclosure from the Inquiry, or the police, despite repeatedly requesting their files for the past ten years. As a result, even though they were involved in groups known to have been spied on, they may never find out the identity of the undercovers who infiltrated those groups (because these officers have been granted full anonymity).

In Sanders’ view, it’s a waste of time to give space to anyone who can’t specify which officer reported on them. He tells us that the Inquiry need not bother hearing oral evidence from such members of the public ‘simply for the sake of it’.

He went on to say some stuff about how public order policing wasn’t just about violence and riots, but about preventing any disruption to a ‘tranquil state of affairs’.

Sexual relationships are not the same as each other

He started well, saying that ‘all sexual misconduct’ by officers was wrong, and should be condemned, not condoned. But he quickly went on to tell us that his clients are upset that their sexual activity (described variously as sexual fumblings, one-night stands and oral sex) might be thought of as some kind of ‘sexual relationship’. It seems they are keen not to be seen as ‘on a par with Bob Lambert’.

Spycops campaigners were astounded to hear him use what was quickly termed ‘the Bill Clinton defence’.

According to him, as so far, we only know about six officers committing some kind of sexual misconduct, the other 30 who served in the SDS during these years are therefore all innocent of such deeds. He claims this would have made it harder for managers to spot the problem.

Furthermore, he says his clients don’t recognise the description – of an institutional ‘culture of sexism and misogyny’ – as something they were part of in the 80s (despite the Met themselves using these words).

He went on to talk about more about ‘sexual attraction’, saying it wasn’t just heterosexual male officers who committed sexual misconduct (as we’ll hear about women officers in future Tranches, and there is one known case of a gay male officer infiltrating the far-right).

Tradecraft Manual

Sanders ended by saying that he was keen to ‘dispel any myths’ about the SDS ‘Tradecraft Manual’ that’s come to light since this Inquiry started.

According to him, it’s just an ‘unfinished draft’, and was never ‘officially endorsed’. However one of the authors of this text, Andy Coles, is scheduled to make an appearance as a witness in December, so he can be asked about this.

4) Neil Sheldon KC

After lunch, we heard from Neil Sheldon KC, who represents the Home Office. The Home Office is considered a Core Participant in the Inquiry, and separately is responsible for funding the Inquiry – no conflict of interests there!

We heard that the Home Secretary awaits the findings and recommendations of this Inquiry with great interest, and has noted Mitting’s ‘public commitment’ to wrap it all up by producing a final report before the end of 2026.

Interestingly, the current Home Secretary, Yvette Cooper, is the first Labour Home Secretary since this Inquiry was first announced by Theresa May. There have been many reshuffles since then, with six different Tories occupying the post in the intervening years, but as we’ve already heard, many Labour MPs were reported on by spycops, and it’s entirely possible that they targeted Cooper (or her father, a prominent trade unionist) at some point.

Their written Opening Statement is online. This has been written to address both Parts of Tranche 2, citing the 2024 General Election as their reason for not submitting a separate statement for Part 1. They hope to add more evidence before Mitting reaches Tranche 5.

It’s all changed now

They fully agree with Mitting’s earlier comments, that:

‘the arrangements for overseeing undercover policing deployments are now very different from those which obtained in the past’.

In the Tranche 2 era (1983-1992), there was no statute law in place to govern the use of undercover officers. Since then, we have seen the enaction in 2000 of the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (RIPA), followed by the Investigatory Powers Act of 2016. The fact that undercover units’ abuses continued well after RIPA came into force shows that it had no real effect on political undercover policing. The problem isn’t what the rules say, but that polce officers ignore the rules with impunity.

Sehldon said that any use of undercovers nowadays must be considered ‘necessary and proportionate’, and be formally authorised at a more senior level than before. Deployments lasting longer than 12 months require the approval of a judicial commissioner.

The law was further amended in 2021, and there is now even more guidance governing criminal conduct by what are now termed ‘Covert Human Intelligence Sources’

The Home Office is keen to prove that ‘the picture is dramatically different today’ from how it was in the years 1983–1992.

Home Office ignorance

Sheldon went on to make a few comments about the evidence seen so far. The Home Office provided annual authorisation – and funding – for the SDS, and correspondence up till 1989 shows that in return they received what he terms ‘a high level description’ of the unit’s work, with reassurances about issues such as officer welfare and supervision, and a few examples of the spycops’ successes.

Sheldon went on to make a few comments about the evidence seen so far. The Home Office provided annual authorisation – and funding – for the SDS, and correspondence up till 1989 shows that in return they received what he terms ‘a high level description’ of the unit’s work, with reassurances about issues such as officer welfare and supervision, and a few examples of the spycops’ successes.

However, they state that they did not seek to direct or monitor the way the unit worked and had very limited knowledge of the actual operations. It was suggested that ‘operational partners’ deliberately kept any concerns to themselves, as they were anxious to avoid the Home Office examining Special Branch/ the SDS too closely.

He says the Home Office did express a direct interest in two particular movements during this era; anti-fascist action and the animal rights movement. He understands that this set of hearings will focus on the officers who infiltrated the animal rights movement.

He reiterated that the Home Office was not aware of any of the ‘deeply disturbing behaviour and conduct’ (by which he meant sexual misconduct, the theft of deceased children’s identities, and any conduct which might have led to miscarriages of justice).

Back in 2020, the Opening Statement provided by the then-Home Secretary referred to a report produced by Stephen Taylor in 2015. According to this, a small number of Home Office officials knew about the SDS’s operations (especially in 1983-86), the identity of some of the groups being targeted and the type of information being gathered about them.

However they were not aware of the issues listed above, and there has been no new evidence since to suggest otherwise (partly because the Home Office has been purged of every document relating to the SDS).

Requests for the Inquiry

The Home Office would like witnesses who make references to ‘the Government’ to be pressed to clarify which branch of the government they are referring to, and not be allowed to use ‘the Home Office’ as a shorthand for the entire apparatus of the British State.

Sheldon’s final point was about an assertion made by HN78 Trevor Morris ‘Anthony “Bobby” Lewis (also aka Carlton King) in his witness statement, about the Home Office deeming the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) to be a ‘subversive organisation’.

When questioned by Counsel to the Inquiry in July, Morris was unable to provide any evidence of this. The Home Office hopes the Inquiry continues to ‘rigorously test’ and seek corroboration of any such allegations in future.

5) Quincy Whitaker

Quincy Whitaker appeared on behalf of John Burke-Monerville, who has also submitted a written Opening Statement for this Phase.

What happened to Trevor

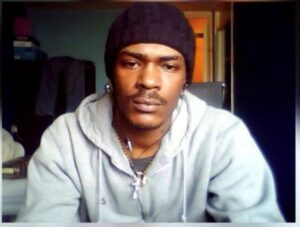

Trevor Monerville

Whitaker began by relating the tragic story of what happened to John’s son, Trevor Monerville. On New Year’s Eve 1986, as a teenager of 19, he went out with his aunts to a nightclub in Hackney. He was seen outside the club, then disappeared, and was found, badly injured and semi-conscious, inside a car parked on a nearby estate.

Instead of taking him to hospital, the police arrested him. His father visited Stoke Newington police station while out looking for his son, and was told he was not there – a lie the police later apologised for.

Over the next few days, Trevor was transferred from custody to Homerton Hospital’s A&E unit and back again several times. Because he was too unwell to attend court, a magistrate visited him in his cell to conduct a remand hearing. From here he was sent to prison – HMP Brixton – with yet more hospital visits, culminating in emergency brain surgery on 6 January.

Medical evidence suggests that his injuries, including the blood clot in his brain, and the memory loss and epileptic fits that plagued him for the rest of his life, were caused by him being beaten ‘multiple times’.

The Crown Prosecution Service finally dropped the charges against him on 8th January, but despite this, Trevor was frequently stopped by the police. By the end of 1988 he had been arrested five more times, although each case was dropped or ended in an acquittal.

Joseph Burke-Monerville

His family were so desperate to help him escape this near-constant police harassment that they put out a fundraising appeal to help him leave the country. He lived in St Lucia for a number of years, but had to come back to London when his epilepsy worsened.

In 1994, Trevor was stabbed 10 times on his way home, in front of witnesses, and died as a result. Nobody has been brought to justice for his murder.

Another of John’s sons, Joseph Burke-Monerville, was shot and killed in 2013, but due to police failings, those responsible were never put on trial.

A third son, David Bello-Monerville, was fatally stabbed in 2019, and the perpetrators found guilty the following year.

As Whitaker put it, this family’s entire lives have been ‘blighted by tragedy, stonewalling, and the consequences of endemic racism’.

The family’s campaign for justice

Understandably, the family have been asking for answers, and accountability from the police, ever since Trevor was first injured, all those years ago. They set up the Justice for Trevor Monerville Campaign (JTMC) and campaigned for a public inquiry.

Understandably, the family have been asking for answers, and accountability from the police, ever since Trevor was first injured, all those years ago. They set up the Justice for Trevor Monerville Campaign (JTMC) and campaigned for a public inquiry.

The entire family have suffered police harassment. Even John’s mother, in her 70s at the time, was arrested on trumped up charges, and successfully sued the police for malicious prosecution.

Burke-Monerville met with ‘Operation Herne’ (an internal police investigation into the spycops operations) in 2016, and was shown a document which mentioned the JTMC, listing it as a group which had been ‘directly penetrated, or closely monitored’ in 1987.

They told him that this didn’t mean that officers had infiltrated his family, just attended meetings around the campaign, adding that the SDS might have made it up anyway, to help justify their operations.

According to them, there were no other records relating to JTMC; they had all been destroyed. The Met then sent him an apology for retaining that document, but not for spying on him and his family in the first place.

More reports have come to light since then, making it clear that the campaign was spied on for at least 9 years. These date from March 1987 – a report in which HN95 Stefan Scutt ‘Stefan Wesolowski’ describes the JTMC and its entirely legal aims – up till February 1996 – a report into preparations for a memorial event on the second anniversary of Trevor’s death.

Interestingly, this last report shows that the campaign had now been allocated a Special Branch reference number of the kind given to people with files for active ongoing monitoring – John wonders why.

We now know that another undercover officer, HN15 Mark Jenner ‘Mark Cassidy’ attended the first such memorial, in March 1995, something John considers a ‘gross violation’ of his family’s privacy.

David Bello-Monerville

Burke-Monerville also learnt for the first time in 2016 that the inquest into Trevor’s death had resumed in 1996, concluding on the same day. None of the family were there. The police told the Coroner that they could not be contacted, and so they were neither invited nor informed. John had lived and worked at the same addresses for many years, and the intelligence report proves that the police knew exactly where the family were in 1996.

He would like this Inquiry to get to the truth of all of these matters. He wants to know why his family’s campaign was targeted by the police, instead of being assisted in their quest for justice. He is keen to hear from anyone with information about any of his sons’ deaths, describing racism in the police as ‘the rotten thread that mats these tragedies and police failings together’.

Despite what the police have said, it is clear to Burke-Monerville that his family was directly targeted by the spycops. There is no evidence that the campaign posed a threat to public order, or that it had been infiltrated by ‘left wing extremists’ (two reasons they’ve given in the past to explain why such groups might have been spied on).

He believes that police racism ‘was at the heart of the police brutality and corruption that the black community experienced’ and ‘underlay the targeting of black justice groups seeking accountability’ for this.

The police don’t like being criticised or held to account

Whitaker drew the Inquiry’s attention to the Met’s ‘excessive interest’ in any groups which criticised the police, especially those who sought to raise concerns about institutional or individual racism in the police.

The Inquiry’s Chair, Sir John Mitting, was reminded that he’d said that he ‘must examine the possibility that the deployments into black justice groups were influenced by conscious or unconscious racism’.

The Inquiry has now published excerpts from the Met Commissioner’s annual reports (covering the years 1983-1994), and these provide evidence of the police’s attitudes towards any groups seeking accountability for police misconduct, who are all seen as ‘anti-police’.

For example, the 1985 report includes a section entitled ‘Divisive Activity’ and later draws a distinction between statutory police ‘consultative’ groups (set up in the wake of the Scarman report) and the other, independent, police monitoring groups, often associated with the GLC Police Committee, described here as ‘purposively hostile to the police’ and not ‘constructive’ enough in their criticism.

Whitaker noted that there was detailed evidence of police officers using extremely crude, derogatory, racist language, and that this went unchallenged, with displays of racist prejudice being ‘expected, accepted and even fashionable’, according to the 1983 report mentioned by Barr this morning. More recent reports (such as Baroness Casey’s review in 2023) find that the Met continues to suffer from a problem with institutional racism.

Now in his 80s, John Burke-Monerville is tired, and considers this Inquiry his last chance for the truth; he hopes it can provide some answers so that future generations don’t have to go through what he has been through.

6) Rajiv Menon KC

Rajiv Menon KC appeared next, representing Richard, Nathan and Audrey Adams, yet another Black family who had been forced to campaign for justice. A racist attack on two of their sons in 1991 resulted in the death of Rolan Adams. Nathan survived this attack, and together with Richard and Audrey, his parents, has submitted a written Opening Statement to the Inquiry.

The origins of racist policing

Menon began by stating that ‘one of the defining features of British policing in the last 50 plus years has been its racism’, and went on to provide the Inquiry with a long and comprehensive list of how this institutionalised racism manifested itself.

He explained that this embedded racism had its origins in Britain’s Empire. A significant number of British police officers in the 20th century – including many Metropolitan Police Commissioners and other senior officers – had backgrounds in colonial and/or military policing.

As Menon pointed out, these colonial police forces were often used to enforce ‘racial, discriminatory and authoritarian laws’. Any opposition to British rule was viewed as ‘sedition’. The police ’had paramilitary training and draconian powers’ and were rarely held to account for abusing those powers.

As the Empire shrank in size, many of these men came back to Britain and took up posts in the Met and other police forces around the UK, binging these attitudes with them.

In Menon’s submissions:

‘Sir Kenneth Newman’s reign as Metropolitan Police Commissioner was a particularly grim time.’

During these years (1982-87) those who opposed racist policing, young black people in particular, were targeted and blamed for the public’s lack of confidence in the force.

Undercover policing was ’blighted by the same racism that blighted every other area of policing’ and there is a danger of this Inquiry ‘reproducing this blight’ unless it starts seriously considering the impact that racism had on the spycops operations.

The attack on the Adams boys

Rolan Adams

The way that the Adams family were spied on, following the racist murder of Rolan and racist attack on Nathan, are a clear example of the way that racism affected the police response.

A photo of the Adams family was shown on screen, as Menon explained the events of 21st February 1991. Rolan and Nathan (aged 15 and 14) had gone to a youth club in Thamesmead to play table tennis. On their way home, they were chased by a gang of 12-15 white youths, shouting racist abuse, who caught up with Rolan and stabbed him in the throat. Nathan was chased but managed to get away, and came back to find Rolan dying.

This was not the first case of racist violence in the area. Other black boys were attacked, hospitalised and in some cases killed in similar racist group attacks. Community groups, such as the Greenwich Action Committee Against Racial Attacks (GACARA), the local council’s Racial Equality Committee and even youth workers from the youth club, had all tried to raise the problem but the police failed to act, or even to recognise the threat posed by far-right and racist criminal groups.

The gang responsible for this incident – who called themselves the ‘Nazi Turn Outs’ – were all known to the police, and described as ‘something of a British National Party (BNP) youth group’.

Even after Rolan’s murder, they were arrested and released on bail, and only one of them was charged with murder. Menon compared this with the police and Crown Prosecution Service’s enthusiastic over-use of ‘joint enterprise’ against other groups of young people. Nobody was ever charged with attacking Nathan.

The police were reluctant to treat it as a racist crime, insisting that it was some kind of deracialised dispute over territory. However the trial judge recognised that this was a racially motivated murder, and said so in his summing up.

Nathan began to be harassed by the police shortly after the attack: as well as being stopped and searched, he was arrested and told that he was banned from going to Thamesmead. The police demonstrated their hostility towards the Adams family in other ways, for example, stopping friends and relatives on their way to visit them.

The Rolan Adams Family Campaign was set up in the aftermath of Rolan’s murder to support his family as they fought for justice. A campaign leaflet was shown on screen. They organised memorial marches and demonstrations, and campaigned for the closure of the controversial BNP bookshop. They reached out to other victims of racist violence and prejudice.

They did not trust PC Fisher, the ‘Family Liason Officer’ assigned to them. They felt that he only pretended to show any ‘empathy’ and tried to ‘tease out information’ from them when he showed up, unannounced, at their home.

They kept getting threatening phone calls, gloating about Rolan’s death, and just a few months after the murder, were advised by the local council that they were in such danger that they should move house immediately. Why did the police not offer them any protection from these threats?

Richard Adams wants an explanation for why the police chose to spy on him and his wife, parents who had just lost a child, law-abiding citizens who just wanted justice after the murder of their son. He asks if a white family would have been spied on in these circumstances.

He says that they long suspected that they were being spied on and that their phones were bugged, but were told they were being paranoid. Nathan now says ‘learning I had been spied on made me a bit sane again’. He goes on to add:

‘I want the Inquiry to get to the truth, to be transparent and to hold people in high places accountable’.

The Adams family feel let down by the police, the justice system and politicians. They believe that if the police had taken more action to tackle racist violence, they could have prevented other murders, like those of Rohit Duggal and Stephen Lawrence, in the following years.

‘Puzzled and angry’ about this Inquiry

They are ‘puzzled and angry’ about a number of issues. They say they have received so little disclosure that don’t know much more now than they did back in 2019, when they were granted Core Participant status.

They reiterate that there is no way that this Inquiry can possibly ascertain the role and contribution of undercover policing towards detecting or preventing racist crime, something which should be of ‘overwhelming public importance’, unless it openly and publicly investigates the undercover policing of far-right and racist criminal groups.

Mitting previously told them that the issue of racist criminal groups would not be covered in Tranche 2 because the SDS did not infiltrate such groups, begging the question ‘why not?’ SDS managers should be asked to explain their targeting decisions.

They note that the Inquiry’s Terms of Reference clearly state that it will:

‘include, but not be limited to, the undercover operations of the Special Demonstration Squad and the National Public Order Intelligence Unit’ (NPOIU)’

The Inquiry is still due to examine undercover policing by units other than the SDS and NPOIU, in Tranche 5, and the Adams family would like confirmation that this issue will be covered then.

So far we have only heard about one deployment involving a far-right group, and this was about HN56 ‘Alan “Nick” Nicholson’ spying on a ‘fairly inactive BNP branch’ in Essex. Mitting has said that the infiltration of far-right groups will only be discussed in ‘closed’ hearings.

The Adams family contend that it is important to hear from as many spycops as possible in open, public hearings. They says there is no value to Non State Core Participants, or the wider public, in the Chair hearing these witnesses’ evidence in secret, and using Restriction Orders to prevent everyone else from accessing it. They ask again for a proper explanation of this level of secrecy in what is supposed to be a ‘public inquiry’.

Mitting popped up on screen to respond to Menon (as always). He confirmed that the SDS had indeed infiltrated right wing groups from the 1980s onwards, but repeated that ‘for reasons that I would hope would be obvious’ that he still intended to hear about these in closed hearings.

For most of us, it is not obvious why this material cannot be heard in public. Plenty of other officers have been granted anonymity and the Inquiry is using screens and voice modulation to protect some from identification. It is unclear why this cannot be done for these deployments, and what the real risks would be.

7) Charlotte Kilroy KC

Charlotte Kilroy KC represents the ‘Category H’ Core Participants (women who were deceived into relationships by spycops).

‘Married 32-year-old undercover police officer (UCO) Bob Lambert dropped five years from his age when, in 1985, he stole a deceased child’s identity as his ‘undercover persona’. During a four-year deployment… he had sexual relationships with four women, fathering a child…

‘In 1987 Lambert’s close SDS colleague 32-year-old UCO John Dines also dropped five years from his age when he stole a deceased child’s identity to infiltrate the same group of activists. He befriended Helen Steel when she was 22 and pursued her as a 24-year-old with propositions of love for months… eventually persuading her in 1990 to enter into a relationship…

‘Dines trained UCOs Andy Coles and HN1… [who] assumed the names and birthdays of deceased children, also losing more than 5 years from their real age…

‘Married police officer HN1, had a year-long sexual relationship with Denise Fuller in his cover name ‘Matt Rayner’…

‘When aged 32, married police officer Andy Coles had a year-long sexual relationship with 19-year-old Jessica, for whom he was her first boyfriend. He has since risen to high ranks within the police…’

The opening paragraphs of Charlotte Kilroy KC’s written Opening Statement hit like punches to the guts. She outlines the misconduct of SDS officers, one after another, until we were left with the impression of something more akin to a predatory sex ring than a unit investigating crime: officers knocked years off their ages and used their training and trade craft to groom and manipulate young and vulnerable women.

In her oral opening statement, Kilroy looked at the devastating impact of that abuse. Her statement focussed on four women: Belinda Harvey, Helen Steel, Denise Fuller, and ‘Jessica’, all of whom will give evidence in the coming months.

Kilroy highlighted the deeply personal and long-lasting trauma caused by the deceptive relationships, exposing the systemic issues of misogyny and institutional indifference within the Special Demonstration Squad and the Metropolitan Police Service.

Bob Lambert and Belinda Harvey

Bob Lambert, a 32-year-old married officer, fathered a child with a woman named ‘Jacqui’ while infiltrating activist groups, before starting a relationship with Belinda Harvey, who was not involved in any of the groups targeted by the SDS.

Harvey, a 24-year-old aspiring accountant, met Lambert at a party in 1987. Lambert, using the cover name ‘Bob Robinson’, quickly pursued her, initiating a romantic relationship within days.

He manipulated her emotionally, altering her lifestyle and encourage her to abandon her career aspirations. Over two years, Lambert maintained the deception, making Harvey believe she had found her life partner.

SDS managers were fully aware of Lambert’s behaviour. They knew he had fathered a child with another woman during his deployment. Kilroy explained:

‘For the Metropolitan Police and SDS management, Belinda’s life and body had little value’

John Dines and Helen Steel

SDS officer HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’, on holiday while undercover

Dines, another married officer, deployed alongside Lambert, targeted Helen Steel, a 22-year-old environmental and social justice campaigner. Ten years older than Steel, Dines befriended her in 1987, apparently at Lambert’s suggestion, and mounted an elaborate campaign to seduce her.

Like Lambert, Dines used various tactics to manipulate Steel, including fabricating stories about his parents’ deaths and even staging a fake arrest to gain her sympathy. Once Steel succumbed to his advances, Dines showered her with love notes and promises of a future together. The relationship lasted two years.

When the time came for Dines to exit his deployment, he pretended to have a breakdown, drawing out his disappearance over several months, even after his deployment ended, leaving Steel devastated.

Kilroy emphasised the cruelty of Dines’ actions, noting that Steel spent years searching for him, genuinely concerned for his well-being, unaware that his entire identity was a fabrication. The SDS, rather than offering Steel any protection or compensation, assisted Dines by moving him and his family to Australia to avoid discovery.

Dines has shown no remorse for his actions, filling his witness statement with insults and false allegations against Steel, furthering her suffering. Kilroy described Dines as a man with ‘so little empathy for other human beings and so much hatred for women,’ calling for a closer examination of how someone so callous could be allowed to operate unchecked.

‘Matt Rayner’ and Denise Fuller

Like Lambert and Dines, ‘Matt Rayner’ exploited Denise Fuller’s vulnerabilities, using her mental health concerns as a means of gaining her affections. He portrayed himself as caring and supportive, but his reports to his SDS colleagues are filled with sarcasm and contempt.

‘Rayner’ initiated a sexual relationship with Fuller immediately after a traumatic life event, and reported on her continuously throughout that relationship, which lasted more than a year. He was encouraged by his managers and his relationship with Fuller was no secret within the unit.

Kilroy highlighted the ongoing injustice Fuller faced, pointing out that Rayner had managed to conceal his real name from both Fuller and the public, maintaining his privacy while she continued to suffer the emotional and psychological consequences of his deception.

Andy Coles and Jessica

The final case Kilroy discussed was that of Andy Coles, who, at the age of 32, posed as a 24-year-old and began a relationship with ‘Jessica’, a vulnerable 19 year old, having had a difficult childhood.

Coles used manipulative tactics to gain her trust, visiting uninvited and hanging around until he could initiate a relationship. Coles groomed Jessica into an awkward sexual relationship – her first – which lasted a year. ‘Jessica’s’ lack of confidence made it difficult for her to resist Coles’ advances.

Coles had since risen to high ranks within the police, becoming head of training for the Association of Chief Police Officers and later deputy Police and Crime Commissioner, all the while callously denying the relationship with Jessica and trying to discredit her with false claims.

Difficult and uncomfortable questions

Kilroy then went on to discuss the ‘difficult and uncomfortable questions’ arising from the evidence, which go beyond the misogyny and sexism of the police and the culpability of individual undercovers and SDS managers. Misogyny alone cannot explain the way the officers behaved.

There is a further sinister and disturbing dimension: while undercover, officers were liberated from ordinary moral codes and:

‘they indulged themselves in a wide range of fantasies, apparently untrammelled by any sense of moral or ethical responsibilities towards other people…

‘They toyed with their victims’ feelings. They often wielded the extraordinary power they were given with breathtaking cruelty or recklessness…

‘Their experiments with these women have left a trail of emotional devastation which continues to reverberate up until the present day.’

Kilroy made the point that undercover deployment in alternative personae effectively released undeercovers from the moral constraints and supervision ordinarily applied by their communities and families, thereby unleashing:

‘a range of dark behaviour for which the men faced no real consequences.’

The SDS leadership, along with the higher echelons in the Met, the Home Office and MI5, should all have been aware that the serious dangers inherent in this kind of undercover operation means such long-term deployments are unlikely to ever be appropriate. They certainly could never be justified in the context in which they were used by the SDS.

It is deeply concerning that they experimented with the lives of the general public and either were not aware, or did not care enough to avoid the obvious dangers.

Kilroy concluded:

‘the Commissioner suggests that the SDS’s infiltration of what he describes as the militant aspects of the animal rights movement was justified, but marred by the misconduct of its officers. He also suggests further justification comes from the evidence of Witness Y, for MI5.

‘This is wrong. It indicates the Commissioner still does not appreciate the serious inherent risks involved in these kinds of long-term deployments. Such deployments are too intrusive and too dangerous ever to be justified in this kind of context.’

The ‘James Bond’ effect

Kilroy also highlighted the role of MI5 in ‘soliciting and perpetuating the conduct of UCOs which led to the abuse of women’.

MI5 were ‘eager and appreciative consumers’ of SDS intelligence and ‘they must have been aware of the tactics used’.

She argued that MI5’s encouragement caused officers to believe they were domestic James Bonds:

‘There is no doubt though that many revelled in the perception that they were a “secret and reliable source”. The idea that they could, like Mr Bond, play fast and loose with both women and the rules seems to have been a powerful fantasy for more than one UCO.’

The culture of ‘backing up’

Kilroy notes that many undercover officers:

‘continue to conceal their own sexual misconduct or that of their colleagues. To this day they feel little or no remorse or empathy for the Cat H CPs [women deceived into relationships by undercover officers].’

She notes how much other undercovers and managers must have known about the relationships and the fact that:

‘the longstanding culture of “backing up” which requires police officers to cover up for each other, even when there has been wrongdoing, continues to take priority over the public interest’.

Eliminating this culture must become an Metropolitan Police goal.

Apologies

The women deceived into relationships are critical of the lack of genuine apologies or acceptance of responsibility from most of the undercover officers.

Coles denies the relationship occurred, Chitty and Dines have declined to cooperate with the Inquiry. Trevor Morris refused to apologise when given the opportunity to do so. Even those who have offered apologies, like Lambert and ‘Matt Rayner’, have done so in ways these Core Participants consider insincere or inadequate.

They welcomed the apologies and admissions made by the Commissioner for the Metropolitan Police in his opening statement, including accepting that at least nine SDS undercovers, including all the officers targeting animal rights campaigns, had engaged in sexual activity with women in this period, which were, in the Met’s own words:

‘a gross violation of the women’s dignity and human rights’.

However, Kilroy noted it:

‘should not have taken until 2024, well over a decade since the revelations about police misconduct became public, for these apologies and admissions to be forthcoming.’

Taking a trauma-informed approach

Kilroy ended her statement by highlighting the profound trauma caused to the women by engaging engaging with the Inquiry itself. It was always going to be hard to read and respond to the evidence of the undercovers who abused them, and to confront their abusers in hearings.

But this inevitable pain has been compounded by lengthy delays followed by extreme pressure to produce evidence in short time frames.

They have been distressed by strict rules prohibiting them from communicating with each other, disregard for their privacy concerns, and disparities in the approach taken to police witnesses.

They are disappointed that no panel members with relevant experience will be appointed to consider recommendations.

They do not consider that the Inquiry has taken a trauma-informed approach, which recognises their special need as victims for fairness and due process. They have suffered as a result.

‘They continue to hope that improvements can be made to the Inquiry process which properly recognise their status as victims, and accord them the special care and respect they need.’

8) James Scobie KC

To end the day, we heard brief opening submissions from James Scobie KC, representing the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), a former leading member of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP), Lindsey German, and Michael Chant of the Revolutionary Communist Party of Britain (Marxist-Leninist). The Inquiry has published a written Opening Statement.

Scobie already made opening submissions on behalf of these clients in Tranche 2 Phase 1 hearings earlier this year, and plans to make more in future. Today’s submissions relate to CND, specifically addressing the continued attempts by both the security services and the police to justify the infiltration of this group.

Those justifications are not supported by the evidence that has now been released. The security service witness, known only as ‘Witness Y’, weakly claims that CND was assessed to have been infiltrated by communists and that it took MI5 until 1985 to work out this wasn’t true.

However, the SDS assessment in February 1982 was that the Communist Party’s influence within CND, and in particular its national council, had waned quite dramatically and was unlikely to grow again. MI5 agreed with that assessment. Witness Y conceded that MI5 did not consider CND to be a ‘subversive’ organisation. So why were they still being spied on?

Witness Y tries to imply that spying on the peace movement was more acceptable then than it would be nowadays. But as early as 1963, Lord Denning said that for most British people it would be:

‘intolerable to us to have anything in the nature of a Gestapo or Secret Police, to snoop into all that we do’.

Spying on CND would have been considered an unacceptable intrusion, a waste of resources and an egregious example of state interference in the democratic process, even at the time.

The most damning proof of that, Scobie asserts:

‘is the Security Service’s own collusion in deceiving the public by stating that they and the Special Branch did not cover law-abiding non-violent activities like CND activities. They plainly did.’

Scobie highlighted the ‘evidential void’ surrounding the decision to target CND:

‘The senior police officers in charge of the SDS between 1981 and 1986 have not assisted the Inquiry. Most of the officers who managed CND deployments have passed away. The documents associated with their period as managers disclosed by the Met Police and Security Services are silent as to both justification and authorisation.’

Chief Inspector Malcolm MacLeod – who has now said that the infiltration of CND was not justified – referred at the time to the decision to target CND ‘coming from his masters’. Those masters were clearly not MI5, because he used that term in documents addressed to them.

Scobie notes that:

‘MacLeod claims that he cannot now remember who he was referring to. In respect of CND, whoever was pulling the strings was bypassing MI5.’

Scobie looked in some detail at internal discussions between the SDS, Special Branch and MI5 about the deployments into CND from 1984 on, particularly the fact that MI5 requested a new officer, ‘Timothy Spence’, be deployed into the SWP. Very unusually, the SDS refused MI5’s request, and insisted he be sent into CND. Once again the ‘masters’, whoever they were, were bypassing MI5 on CND targeting.

The Home Affairs Select Committee set up an inquiry into Special Branch’s activities in 1984, and a number of other incidents around that time raised serious questions about the targeting of CND.

There was widespread public denunciation of the investigations into Madeleine Haigh. Haigh was a CND supporter who wrote to her local newspaper protesting about the cancellation of an anti-nuclear event in Worcester. Shortly afterwards she was visited by two policemen who claimed to be investigating a mail order fraud, but turned out to have come from Special Branch.

Cathy Massiter was an MI5 intelligence officer who was tasked with investigating left-wing subversive influence within CND, and became a whistle-blower after leaving the job. In 1985 she appeared in an episode of Channel 4’s 20/20 Vision programme, entitled ‘MI5’s Official Secrets’, saying:

‘We were violating our own rules. It seemed to be getting out of control. This was happening, not because CND as such justified this kind of treatment but simply because of political pressure; the heat was there for information about CND and we had to have it.’

Chief Inspector Wait claims not to recall any discussions with senior Special Branch managers about the justification for infiltrating CND, and not to recall why he refused to go along with MI5’s requests to deploy ‘Spence’ into the SWP.

Astonishingly, there is no mention of Cathy Massiter in his statement, even though he acknowledged the breach of SDS security in an Annual Report at the time, and as Scobie says, the impact of her revelations would have caused ‘unforgettable’ panic within Special Branch at the time.

Scobie asserted that the Inquiry has received ‘no assistance’ from SDS managers ‘on the issues of justification and authorisation’.

The Met has offered two outlandish suggestions as possible justification:

‘concern that CND could be infiltrated by communist groups and the KGB’ and ‘venturism around the US air bases could lead to protestors being shot.’

Neither assertion is backed up by the evidence. If evidence does exist, the Commissioner should look to the Met Police’s own documents and disclose them.

Scobie then reached the heart of the matter:

‘The Commissioner submits that the Metropolitan Police Special Branch was obliged to monitor the CND, linking that obligation to significant government and military interests in the 1980s. That is the firmest indicator yet of where the authorisation for the CND deployments came from. Government targeting.’

Scobie examined relations between the Met Police and the Home Office in the early 1980s, and described a rift which developed around 1983.

That year, Special Branch produced a report with the title ‘Political extremism and the campaign for police accountability in the MPS district’, about the efforts of the Greater London Council (GLC) police committee and others to hold the police accountable for their actions. The report was politically partisan, and the response from the Home Office expressed ‘very serious concern at the breadth and tone of, and market for, that report’.

Deputy Assistant Commissioner Hewett replied on 4 March 1983:

‘We are dealing here with a broader concept of public order intelligence, and on this particular aspect I probably had gone as far as the Special Branch should go.’

There was nothing in the report that could be said to relate to public order. The Home Office saw that the response did not stand up to examination, and it was Hayden Philips’ view that Special Branch had gone too far, by looking into legitimate political activity which could not be considered subversive.

What is most interesting about this is that the most senior Special Branch officers had decided not only that they could use Special Branch resources, including the SDS, to resist lawful attempts by a democratically elected council to make the police accountable to the community they were supposed to be serving, but also that they could do so despite having been told by the Home Office that they could not, and having said that they would not.

Scobie made clear:

‘This was a wilful assault on democratic activity, acting beyond police powers with knowingly unsustainable justification, in contravention of an order from a Government Ministry…

‘They would not have acted in this manner unless they were confident of support from an authority higher than the Home Office.’

There is evidence that in February and March 1983, Special Branch were engaging directly with the highest levels of government. Margaret Thatcher made a direct and specific request to the police in respect of intelligence on the police accountability movement.

The same appears to be the case for CND. Chief Inspector Martyn MacLeod has indicated that he would not be surprised if the Prime Minister had a role in tasking because ‘the whole thing became very politicised’.

National Archives releases from 1983 show a government scared of losing the battle of public opinion on disarmament. The Prime Minister’s office was devising ways of neutralising CND.

It seems MI5 let the Government down by rightly refusing to cooperate on party political issues targetting law-abiding groups. The evidence now suggests that the Met stepped into that void.

This evidence comes on top of the arguments outlined by Scobie earlier this year in his opening statement to Tranche 2 Phase 1 about the creation of the Ministry of Defence DS19 Propaganda Unit, and Michael Hessletine’s use of SDS intelligence to undermine opposition to the government in the general election of 1983.

The 1984 SDS annual report has a section on CND, but its focus was not on public order or subversion; it was on (a) membership numbers; (b) the political position, noting the Labour Party’s official espousal of unilateral nuclear disarmament; and (c), that:

‘CND has skilfully manipulated public opinion over issues about which people are genuinely concerned.’

He ended his submissions with some comments on disclosure, or rather, the lack of it.

The evidence provided MI5 is ‘woefully inadequate on an issue of such importance.’

In respect of the Met Police, there is evidence of ‘a high level Special Branch directive that led to all files on CND being destroyed. While there may have been some justification on the basis of the Home Office guidelines for destroying files on the individuals, there can be no justification for the destruction of files on policy, liaison, authorisation and justification.’

Scobie urged the Inquiry to investigate this political interference further and to focus not only on the role of the Home Office but also on the engagement between the Met and the Ministry of Defence, the Cabinet Office and the Prime Minister’s office, noting that:

‘[CND] had hundreds of thousands of members in local branches and nationally. The CND was a mass democratic movement of ordinary people, but like governments before, and since, the Thatcher Government was terrified of two things: first, a mass movement of people; and, secondly, democracy itself.’