UCPI Daily Report, 20 Oct 2025: Dennis ‘Ben’ Gunn evidence

Tranche 3 Phase 1, Day 5

20 October 2025

Spycop chief HN143 Ben Gunn at the Undercover Policing Inquiry, 20 October 2025

INTRODUCTION

Spycop boss HN143 Dennis ‘Ben’ Gunn gave evidence to the Undercover Policing Inquiry on 20 October 2025 at the International Dispute Resolution Centre in London.

Though the Inquiry has started its ‘Tranche 3 Phase 1’ hearings, examining the final 15 years of the Special Demonstration Squad 1993-2008, Gunn was actually a holdover from Tranche 2, which covered 1983-1992.

Gunn was commander of operations for the Metropolitan Police Special Branch from February 1988 to November 1991. This meant he had oversight of all the operational work of the various Special Branch squads, including the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS).

The Inquiry’s page for the day has video and a transcript.

The Undercover Policing Inquiry (UCPI) is an independent, judge-led inquiry into undercover policing in England and Wales. Its main focus is the activity of two units who deployed long-term undercover officers into a variety of political groups: the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS, 1968-2008) and the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU, 1999-2011). Spycops from these units lived as activists for years at a time, spying on more than 1,000 groups.

Gunn has provided a witness statement to the Inquiry [MPS-0749634]. Questioning him was Sarah Simcock, her first appearance as Counsel to the Inquiry.

Gunn is in his 80s but comes across as someone still sharp, though there are some blanks in his memory. He demonstrated the attitude of someone certainly used to wielding authority, not used to being questioned. He is not afraid to express his opinions on matters.

He could also be quite patronising and talked down to Simcock when she drilled down into the version of events that he wanted to present.

This is a long report, use the links to jump to a specific topic:

The Man and His Mission

Gunn’s career and outlook

The Scutt Affair – Reputations At Stake

Stefan Scutt, the spycop who went off the rails. His breakdown and the desperate measures taken to protect the secrecy of the unit

Spycops Methods

Oversight, stealing dead children’s identities, operating beyond the law

Relationships

Officers deceiving women into long-term intimate relationships

Criminal Spycops

Officers arrested under false names, deceiving courts, and their managers’ efforts to protect them

SDS Targeting Strategy

Who they spied on and how they justified it

Public Disclosure

The True Spies documentary and the public inquiry

The Man and His Mission

Sarah Simcock, who questioned Gunn for the Inquiry

As commander of operations for the Metropolitan Police’s Special Branch (February 1988 to November 1991) Gunn was in charge of many intelligence gathering units, including the SDS. He had not formally played a role in the SDS prior to this, but that did not stop him having very firm opinions about it all.

It is worth nothing that from the outset at the Inquiry, Gunn exhibited a tone that we have not seen before. He wasn’t combative, but at times he bordered on the aggressive, leaning forward and displaying anger. Particularly so when lines of questions took him into areas where he had strong views on the appropriateness of matters.

Repeatedly, he would return to restate points such as how upset he was that interviews given to Operation Herne, the Metropolitan Police’s internal investigation into the spycops scandal, had been given to the UCPI.

GUNN RIDES TO THE DEFENCE OF THE SDS

Gunn’s took the position it was only ten or so officers who had let the side down, and the Inquiry was simply not hearing about all the great stuff the SDS had achieved to prevent the collapse of civilisation.

He was determined to be the voice of all the SDS officers he considered as having been wronged. It became clear that he is following the Inquiry closely, listening to much of the testimony.

If officers such as HN10 Robert Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’, or HN78 Trevor Morris ‘Anthony “Bobby” Lewis’ came off as tone deaf, Gunn took it another step forward. It was difficult listening. However, in his eagerness to defend the SDS, he also let a lot out of the bag in the process, demonstrating the value of hearing such witnesses live rather than just taking written statements.

Being questioned about events from forty years ago while now an elderly man, Gunn could be expected to have poor recollection. There were things he could firmly answer, but there were quite a few topics where he simply had no recollection whatsoever, not even vaguely, which he said bothered him. However, he was clear he stood by his decisions at the time and the minutes that went with them.

PROTECT THE POLICE

He didn’t shy away from anything in this respect and felt able to justify why decisions were made as they were back then. Pretty much that came down to the need to protect the police, the Home Office and government more generally from embarrassment had certain matters being made public at the time – which included even the existence of the SDS.

This embarrassment was another regular theme of his: he was determined to ensure that the good, honest, hard-working police officers of Special Branch were not going to take the blame for just doing what they had been told to do by their political masters.

It was clear he had come with points to make, and he would make them at every opportunity. In the process, he would demonstrate his annoyance with the questions coming from Simcock that made him repeat what was so obvious to him. For him, it was all part of the Inquiry having the wrong approach and not considering all the laudable work that the SDS had done.

One came away from his evidence with a sense that there is disquiet among the former Special Branch managers that the Metropolitan Police has been shifting its stance to condemn the SDS.

At the outset of the scandal, the MPS relied on the ‘rogue agent, bad apple’ excuse. However, as more became exposed, it was the undercovers to blame. As the managers gave evidence, even that limited damage control became untenable with the managers increasingly shown to be incompetent or turning a blind eye.

Finally, the Met seem to have begun washing their hands of the entity of the SDS as the evidence has become overwhelming. At the beginning of Tranche 3 they conceded it was ‘a dysfunctional unit’, an admission forced by the Inquiry’s publication of the Met’s damning internal Closing Report [MPS-0722622] written when the SDS was shut down back in 2009.

Now the senior managers from the time, such as Gunn, can apparently see the spotlight slowly shifting to them, and with it the entire reputation of their dearly beloved Special Branch. As such, his fighting approach can be seen in this context.

OPENING SALVOS

The first question from Simcock is whether Gunn spoke to other current or former police officers before making his witness statement.

Gunn is quick to set the tone, rushing ahead with:

‘If I could just explain: I was a coordinator of a group of former senior Metropolitan Police Special Branch officers. That group, of which there were 15 of us when we started, sadly there are only seven left, that group was formed and I coordinated it to help this Inquiry with factual information of the background to the SDS.

Under no circumstances did we collude in any way, shape or form on the evidence presented or would be presented by potential witnesses.’

He added he had spoken to Piers Doggart, Solicitor to the Inquiry, to whom he had:

‘made it absolutely clear that whatever we discussed in terms of former colleagues it was not about the evidence, it was about process, facts and help.’

This included his close friend and colleague HN587 Peter Phelan. A Special Branch officer who was Gunn’s predecessor as Commander of Operations, for a time Phelan was directly above Gunn as Deputy Assistant Commissioner – Specialist Operations/ Security (DACSO).

Phelan was due to give evidence in the same week as Gunn but was withdrawn due to ill-health. We have been told he will be rescheduled.

Gunn says he is in contact with Phelan:

‘but under no circumstances would either of us talk about the evidence. And we were absolutely sacrosanct in making that distinction when we spoke to one another. We are friends and former colleagues, but under no circumstances did I collude in any way talking about the evidence that either he or I give.’

Simcock then points out that the Inquiry asked both Gunn and Phelan the same questions about knowledge of relationships.

Gunn’s responses to them are at paragraphs 131 to 133 of his statement, and Phelan’s at 144 to 146 of his statement [MPS-0749627]. She notes that they are similarly worded and in fact, bar one word, the middle paragraph is identical.

Gunn says he’s unsurprised because the question was the same, and again denies any collusion with Phelan.

CAREER

Gunn had been Detective Chief Superintendent in charge of R Squad, that part of the Metropolitan Police Special Branch which dealt with policy, communications and statutory powers.

Protest against Huntingdon Life Sciences vivisection laboratories in Cambridgeshire, where Gunn was Chief Constable

Unfortunately, this is all we learned as, despite questions being submitted by core participants, the Inquiry didn’t feel the need to explore this aspect more.

It is hard to see how R Squad is not relevant, as this department was not just responsible for overseeing policy and statutory powers, but was also where top-secret policy files were kept. Even if it is not of direct concern, why it didn’t play a role in oversight of the SDS ought to have been explored.

Following this Gunn did a stint as a uniformed Chief Superintendent in Area 6 (West London) from 1986 to 1987. This was something senior officers did as part of their progression to higher positions.

From February 1988 he succeeded Phelan as Special Branch’s Commander of Operations.

In late 1991, Gunn left the Metropolitan Police, having been appointed Deputy Chief Constable of Cambridgeshire Police – going on to become Chief Constable. There, among other issues, he dealt with hunt saboteurs and animal rights campaigns, particularly in relation to the notorious vivisection laboratories at Huntingdon Life Sciences.

COMMANDER OF OPERATIONS

It is Gunn’s time as Commander of Operations that is of most relevance to the Inquiry. He is the first officer to give testimony who held this senior position.

He did not really have a handover from Phelan, but didn’t need one as they had worked closely together for 30 years and he knew what the job entailed. If he had any questions, they had adjoining offices so could speak at any time. Had there been anything sensitive to know about S Squad, they would probably have discussed it, but he doesn’t recall any specifics.

At the time the Deputy Assistant Commissioner – Security was the Head of Special Branch, with the Commander of Operations (also at this time at commander rank) being the effective deputy.

Commander Ops, as it was known, had responsibility for all operational work carried out by the Met’s Special Branch. This included the SDS, which sat in S Squad but moved to C Squad (which monitored left wing political activism) in 1988. Alongside him was Commander Administration – at that time HN295 Don Buchanan who would later succeed Gunn as Commander Ops.

Every morning at 10am, all the senior managers, including Phelan, Gunn and Buchanan, met with the Detective Chief Superintendents of each of the Special Branch squads. Also there was George Churchill-Coleman, the Commander of SO13 Anti-Terrorist Branch. They discussed the business of the day as it affected the different squads, and made decisions (this was the ‘prayer meetings’ mentioned by other senior Special Branch managers).

Gunn is questioned on who would have known of the SDS at this rank. He replied that until an officer reached Commander rank, most Special Branch officers ‘did not appreciate the full remit or the existence of the SDS’.

He is certain the senior ranks of Assistant Commissioner, Specialist Operations (ACSO) and the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police were aware of the unit, in the sense of what they were doing, though not about the day-to-day running or the techniques and tactics used.

It is at this point, only 15 minutes in, that Gunn makes a statement he would return to repeatedly:

‘And don’t forget we did this work on behalf of the State. We were asked to do this by the Home Secretary in 1968, when the febrile atmosphere of demonstrations and extremism in this country was much greater than it is today.

And I don’t know how many of the Inquiry team were experienced and understand what we went through in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. But it was important that the Commissioner, who was asked by the Home Secretary in 1968 to get our act together on the intelligence side, we were performing those duties on behalf of the State. For the State.

And don’t forget, we had no statutory power to do what we were doing at the time. We were operating in a statutory vacuum – and that meant we had to make decisions on what we did from our own pragmatic knowledge, staying within the law.’

OVERSIGHT OF THE SDS

The SDS, a small unit in itself, was accordingly a relatively small part of Gunn’s responsibilities as Commander Ops. He had other issues such as terrorism to deal with. He didn’t ignore the SDS, but left it to the Chief Superintendent of S Squad to inform him of operational and reputational matters.

Hence, Gunn did not involve himself in the day-to-day management of the SDS, but had an oversight role. Asked that that oversight meant, he replies:

‘Well, the oversight of the SDS was demanding that they stayed within the law, that they perform their duties properly. Both from a discipline and criminal law aspect and any matters that affected the reputation of the Metropolitan Police would obviously need to be brought to my intention…

But I would have been informed in any matters that affected the reputation and the operational credence of such a unit.’

Hence, he only became involved in SDS matters when they were referred to him. He didn’t have a daily meeting with the Chief Superintendent of S Squad about the SDS (HN103 David Smith, HN115 Tony Wait), and Gunn had sufficient confidence in them to be telling him what he needed to know. They were in charge and he, Gunn, relied on their operational judgement.

Matters he would expect to be referred to him were:

- any arrest of an undercover, whether in real or cover identity

- any prospective disciplinary issue

- any substantial increase to the public risk to an undercover officer, whether as a result of suspicion by targets or otherwise

- any welfare issues that required the support of the wider Met or outside agencies

It is only 19 minutes in, and Gunn interjects into the questioning to make the second of the points he was determined to hammer home throughout his evidence:

‘Could I just put into context some of what you are asking? The matters of the SDS, it was a highly sensitive and secret operation [redacted] and it was on behest of the Government and the Home Office that we performed such duties.

An overriding consideration for all matters affecting the SDS was the reputation of the Metropolitan Police and the Home Office and the Government, that these very sensitive issues are not traded about daily so that it would become an embarrassment to the Home Office and Government.

We were operating under that pressure, when everything we did we had to bear in mind the fact: was the reputation of the Metropolitan Police going to be in jeopardy if information leaked on some of the things we were doing?

And that to some extent explains some of the rationale that I put later when dealing with the arrest of people, undercover officers and/or informing or not informing the court.’

He is asked who within the Met would see the SDS Annual Reports. Phelan did, and if necessary the Commissioner himself. Ask why the Commissioner would see them, he is back on his hobby-horse:

‘Because, as I explained, the delicacy and sensitivity of much of the work we were doing on SDS was unique. It had not been done before. It’s helpful to the Inquiry to distinguish between undercover policing as we knew it at the time and the new form of undercover, deep-cover policing, that occurred with the SDS.

The two are different and I am not absolutely sure that this Inquiry has entirely understood the difference between what we started to do uniquely in 1968 and what was going on in terms of the normal undercover work in respect of crime.’

Gunn brushes over the fact that the SDS had been going twenty years by the time he came along, and predated the formalisation of undercover work elsewhere in policing including the Met. But the point he wants to drive home here, as well as later, is that the Inquiry doesn’t understand how special and unique the SDS were.

The Scutt Affair – Reputations At Stake

Even by SDS standards, the actions of HN95 Stefan Scutt, ‘Stefan Wesolowski’, was one of the lowest points in the unit’s history. Infiltrating the Socialist Workers Party in 1988, this undercover went off the rails spectacularly.

His withdrawal from the field appears to have tipped him over the edge, causing him to act erratically and eventually leading to him retiring on medical grounds – rather than facing disciplinary proceedings for his actions.

It created an existential crisis for the SDS, which it ought to have learned lessons from. However, such lessons were not really learned. As such it has been a point of focus by the Inquiry when questioning multiple officers, particularly how decisions were made and especially what motivations underlay choices made by senior managers.

Gunn was closely involved at the time as Special Branch sought to contain the fall-out. However, he states he has no recollection of it whatsoever. He doesn’t deny he was involved in the decision making process and involved in the aftermath, but just doesn’t recall any of it and he cannot understand why he does not remember, and is troubled by that.

However, having read the documents, he does not think he would have done anything differently. Regardless of this, he’s asked questions and his responses are illuminating in their own way, not least in how his answers demonstrate his mindset as a manager.

Issues such as possible criminality by spycops, welfare and disciplinary matters would have been decided as a whole rather than being compartmentalised. They would be part of the totality of the decision-making process.

Counsel to the Inquiry asks if there was generally a prioritising of SDS operational security and the secrecy of the unit over potential disciplinary or criminal investigation of an undercover.

‘Ms Simcock, as I mentioned in an earlier answer, there was an overriding concern that the secrecy of the SDS and the classification of the work of the SDS should be kept to an absolute close need to know. And, yes, it would have been a consideration in making judgements on whether or not a discipline or a criminal case would follow a particular incident.’

Counsel does not rise to his patronising tone, and asks whether there was a concern that if the Scutt affair became public there was a risk the SDS would have been closed down.

‘Well, it just wasn’t Scutt. Any detail in respect of the work of the SDS – and I can’t emphasise highly enough it was a top secret unit operating in a statutory vacuum at the behest of the Government/Home Office.

And as far as the [Special] Branch were concerned, any handling of SDS information, intelligence, et cetera, had to be at the highest and most discreet level because of the embarrassment it could have been caused to the Home Office and to the Government if the work and understanding of the SDS had been made public at that time.’

Pressed on this, he says that maintaining the secrecy and operational security of the SDS was not a deciding factor in decision-making, but it was a significant one. He and the head of S Squad would have taken into account:

‘the need for the utmost secrecy of this operation. And I can’t emphasise that enough. And that was not our doing, that was the Government and the Home Office wish.’

COVERING UP CRIMINALITY

Counsel asks about whether there was a concern that a culture of covering up criminality had developed in Special Branch, and whether that was a necessary consequence of the level of secrecy.

Gunn says no, he doesn’t think there was such a culture of secrecy to avoid doing things or admitting things. Rather the culture of secrecy was about the very existence of the work of the SDS:

Q: But if criminality or misconduct on behalf of undercover officers became public, that secrecy would be in jeopardy and therefore the unit itself and its existence could be in jeopardy?

A: Obviously. And that was part of the decision-making process that I and others had to make when it came to the delicate area of undercover officers committing criminal offences.

And we had to take into account not just the circumstances of the case, the overriding need of the interests of justice, but also the overriding need of the Government and the Home Office that whatever action we took should not jeopardise the publicity of SDS activities. And I can’t emphasise that enough.

Asked why he would have recommended Scutt be removed from the list of authorised firearms officers, he explains:

‘Well, obviously, we were taking into account the risk [Scutt] posed to himself and to the organisation in respect of the activities or alleged activities.’

It’s extraordinary seeing a high ranking police officer admit that the SDS was operating outside of any legal basis, its officers were permitted to commit crimes because disciplining them would risk them becoming disgruntled and exposing the unit’s existence, and yet he talks about this as if it were all right and proper.

TO DISCIPLINE OR TO RETIRE

Gunn stands by the judgement to let Scutt retire on an ill-health pension rather than following a disciplinary route. He states that welfare considerations at the time in the police were not sophisticated, and they didn’t know the potential psychological damage undercover work was doing to the officers. That said, he suspects they wouldn’t have dealt with Scutt differently if they’d known, but they would have been forewarned.

It’s also clear from his contemporary minutes to Phelan that Gunn preferred to take the medical route rather than disciplinary in dealing with Scutt. This was apparently less about the welfare needs of the troubled undercover, than, as Gunn recorded at the time [MPS-0740892]:

‘the very real possibility of compromising his position in his covert role and possibly other S Squad activities. I did not feel it prudent indeed practical to launch into a discipline investigation at that time’.

Counsel asks about the thinking behind him writing that, to which he responds:

‘Well, I think as I have already explained in some detail, there was an overriding need to protect the security, sensitivity and classification of the SDS’s activities. It would have been a feature and a very strong feature in my decision, as indeed was shown by the minutes…

I felt it was best for Scutt and it was best for the Metropolitan Police, and, I have to say, it was best for the Home Office and Government, that he should be allowed to retire in a dignified and quiet way, rather than the paraphernalia of a discipline case which would have attracted huge publicity.’

He is pressed if publicity was an overriding factor. He says no, but it was nonetheless a powerful factor in the consideration.

Could he have done both disciplinary proceedings and ill-health retirement at the same time? No, he responds, because it would not have solved the issue of publicity. It was agreed by him and other senior managers that ill-health was best for all concerned. And he wouldn’t change that now.

It is clear that Gunn has, in his own mind, made a distinction between cover-up and keeping things secret – the latter being the way he can justify dubious decisions – and he will not deviate from this. It is his version of plausible deniability that he will rely on to justify his management of situations as the issues on his watch mount up.

It’s noted that after this decision was made Gunn met with medical professionals involved with treating Scutt. He says he would not have brought pressure to bear to go down that route, and that would have been ‘wholly improper’.

OUR SIDE OF THE BREAKDOWN

Counsel notes that Gunn had minuted to Phelan that he had spoken with the consultant psychiatrist treating Scutt and emphasised ‘our side of the case’.

He is asked what that might mean, to which he answers that would have been about the sensitivity of what Scutt had been doing.

‘I don’t think he would probably have been aware, but the sensitivities of explaining the background to the work the officers were doing, which I say again was unique, we haven’t done this before, we were on the rim and the outside of the law on many occasions and these issues had to be based upon judgement taken in good faith at the time.

And 40 or 30 years later, trying to rewrite history and/or reassess the circumstances that we were under then I think is not particularly fair.’

There he is again, even more clearly admitting that he knew the spycops’ remit was unlawful, but claiming it’s unfair for the Inquiry to objectively judge what they did.

Continuing with Gunn’s reaction to Scutt’s breakdown, Counsel notes that he recorded at the time:

‘I reiterated to the doctor our concern in this case both about the sensitivity of the issue… and the need to protect our continuing operations. I also mentioned our concern about the alter ego problem.’

The note recorded that a consulting psychiatrist, Dr Farewell, had told Gunn that given his condition, Scutt should not be seen by any police officers until further notice.

Counsel points out that he ignored this advice and got Phelan’s permission for SDS manager HN337 to visit Scutt to recover documents relating to his cover role.

She said that the Inquiry understood their recovery was necessary to prevent compromise of Scutt’s undercover work and SDS operations more generally and to protect the safety of his colleagues still deployed.

She asked if that was right, to which he answered:

‘I think that’s entirely sensible.’

Once HN337 had successfully done this did Gunn instruct that no other police officer should contact Scutt, as he was concerned about Scutt’s mental health and welfare.

Gunn met with the Met’s Chief Medical Officer, Dr Bott, and the consulting psychiatrist, Dr Farewell. Following this meeting, they agreed [MPS-0740892]:

‘The pressing operational need to assess potential damage limitation factors overrode potential concern for Scutt.’

Gunn recorded that Dr Bott was happy with Special Branch’s actions to date in a memo to Phelan, adding:

‘I am now confident that adequate damage limitation measures have been taken to protect SDS activities and I am hopeful that that aspect of the Scutt affair has been resolved.’

ABSCONDING TO YORK

As part of his breakdown on being told his deployment was ending, Scutt vanished, only to turn up in a distressed state in York. He was detained by local police there, who found his Met personnel assessment paperwork.

Gunn visited North Yorkshire Police to find out what they had on Scutt. He is troubled he cannot remember this, but thinks he must have seen someone at assistant chief constable level or higher, and have been driven to Yorkshire and back.

He adds:

‘But whatever happened it would have been for the specific purpose of maintaining the security of the SDS in respect of the reputation of the Metropolitan Police and the need to know.

And if we had information around Scutt’s activities in North Yorkshire or elsewhere, then we would need to verify and/or try and minimise the damage that could potentially have been caused from that.’

Counsel notes that records say North Yorkshire Police agreed to destroy records. Gunn doesn’t recall that, and doesn’t know why he would have wanted the paperwork destroyed:

‘We weren’t trying to hide anything. But again, if I said that, I can’t recall why.’

He agrees that he likely sought assurance that they wouldn’t disseminate anything they’d been told further.

Shortly afterwards, Gunn adds:

‘It is unfortunate that Scutt not only broke his cover but also reprehensibly gave details of the nature of his SDS work to unauthorised persons.

I fear that little will be achieved in pursuing any disciplinary action against Scutt. Indeed, we have more to lose.

Suitable damage limitation has been taken in respect of North Yorkshire Police Force and I feel this particular facet of the Scutt saga must rest there.’

Why did you consider there was little to be achieved by pursuing disciplinary action? Again, Gunn is emphatic that going down the disciplinary route would risk the severe downside of publicity.

‘I stand by the judgement I made in respect of the sensitivity and security needs of the work that Scutt was involved in, and the potential for that matter becoming public with the huge danger and difficulty it would create both politically and police-wise for us and Government.’

GOVERNMENT INVOLVEMENT

It’s only an hour in to his day at the Inquiry, but it is already apparent that Gunn is very keen to bring the Government in whenever he can.

He does however accept that the reputation of the Met would have been an issue for making that judgement and agrees that if the Scutt affair had become public the SDS’ existence would have been in jeopardy.

In a regular feature of his evidence, he immediately adds:

‘The efficiency and effectiveness of the SDS at the time in terms of the information it was providing, the intelligence it was providing, was crucial to the Home Office, to the Government, to the Security Service at the time.

So it wouldn’t just have been a question of the SDS folding. That vital intelligence that we were asked to gain – which we did over the years – would have gone. Where is the vacuum that would have filled that? And I think we are viewing some of that today with the mismatch between intelligence and public order problems.’

We see again his determination to defend the SDS and what it was doing, bigging up (without ever substantiating) the value of its work.

Gunn’s eagerness to say that the government directed the spycops is startling. Other police witnesses at the Inquiry have downplayed everything and refused to point the finger of blame higher up the command chain.

The Home Office: set up and funded the SDS for 20 years, received annual reports, yet retained no documents whatsoever.

Gunn is so emphatic that it’s easy to read it as an attempt to avoid the blame, and maybe that’s all it is. But then again, it does fill a few of the major blanks.

The big question, far beyond what the spycops did, is who ordered it. The Home Office set up the SDS and directly funded it for the first 20 years. It received annual reports detailing what was done. The funding was renewed annually.

Right at the start, government documents showed that they felt the secrecy about the SDS’s existence was paramount, fearing ’embarrassment to the Home Secretary and HM government’.

So, they knew the public would be outraged, and they knew they wanted plausible deniability.

Despite two decades of working for the Home Office, a search of all Home Office archives found that not one document about the SDS has been retained. This can only be to ensure that if – as has happened – the public did find out about the SDS, the blame stays with the police rather than their paymasters.

AND MI5 TOO

It’s not just the government that Gunn has his eye on. When the interest of MI5 in the Scutt affair is raised, he cant recall the detail, but is quick to declare:

‘The Security Service knew exactly what we were doing in the SDS. They lived off the product. They enjoyed the product. They even targeted and helped targeting. So it’s important that the Security Service were part of the equation when it came to decision-making process on all matters dealing with SDS that might affect the Security Service work.

And it is no good saying, “I was upstairs collecting fares at the time”. They were involved in most of the work of the SDS, particularly in the early days when we were dealing with subversion, extremism left, which was the Security Service’s province.

And I think I have to say, having listened to each of the tranches, every bit of evidence that’s been delivered to this Inquiry so far, I don’t see much from the Security Service in terms of supporting or justifying what we did in those days. And I think that is a matter of concern.’

Gunn doesn’t like to miss an opportunity to make criticisms of the Inquiry’s approach to things. It’s clear he has been following the Inquiry’s progress avidly and is not happy with its conduct, not least because the fine men of the SDS are not getting the credit he thinks they deserve, while the government and MI5 don’t get the same scrutiny.

Counsel ask if, at the time, there was any consideration that the influence secrecy and security of operations had over decision-making was setting a dangerous precedent?

‘Well, Special Branch had many experienced and diligent officers at all levels. Although you would be surprised thinking it from some of the details that have been presented to this Inquiry.

But the experience of the Special Branch officers – particularly the managers – in conjunction with the Home Office, in conjunction with the Security Service, there was a common agreement. And I can’t emphasise this enough.

There was a common agreement that the secrecy and confidentiality and knowledge of the work of the SDS should be kept to an absolute need to know. And that need to know, I don’t think has fully been explained yet to this Inquiry.’

Gunn is the man to do that, apparently. Though no other manager has said nearly as much as he has done. In his determination to defend the SDS and by extension Special Branch, he is content to throw everyone else under the bus. Seemingly, as we’ll see, because in his eyes that’s what’s happening to them.

Before the Stefan Scutt debacle, there had been the case of HN155 ‘Phil Cooper’, who was also retired on ill-health. He had infiltrated the Socialist Workers Party 1980-84, and was on close terms with some MPs. He wrote a letter to the Commissioner complaining about his treatment in his disciplinary case.

Gunn is asked about whether there would have been a concern about someone like this raising a disciplinary matter with the Home Secretary.

He answers that it was not about the individual case but any disciplinary inquiry would have been public and hence the exposed the SDS:

‘It was about the circumstances that the Home Office would need to have known if there was a reputational issue coming their way.’

SCUTT, MI5 AND THE HOME OFFICE

Counsel returns to MI5’s interest in the Scutt affair, and a note of a meeting they had with SDS managers. In it they note that nobody was going to say anything about the matter to the Home Office [UCPI0000030663].

In his written statement to the Inquiry, Gunn said Scutt would have been an operational matter for the Met police not the Home Office whose role was just policy and funding, so Scutt’s removal and welfare concerns were matters that were solely the concerns of the Met.

He adds, unprompted:

‘And I think it underlines again what I tried to say earlier, that the Security Service were head and shoulders and above dealing with these matters in respect of keeping the secrecy of this operation sacrosanct and we, in addition to the Security Service, would take into account the position of the Home Office and Government in making those judgements. And that, I believe, is the clear implication of those minutes.’

Counsel presses whether the real reason is the Home Office would have cut funding if they found out. Gunn doesn’t like the question.

‘No, that’s your judgement and I don’t agree with it. It would have been an issue. And, as I’ve said, the Home Office was very sensitive about the activities of the SDS and how we controlled the need to know.’

He doesn’t think it would have necessarily cost the SDS its funding, adding:

‘The [Home Office] knew that these were very sensitive, difficult operational matters. So the line between operations and policy in respect of the police, the Security Service and the Home Office was a thin one, but it was very important.

And we had to take into account the sensitivities of each of those players, if I can put it that way, in respect of any action that was taken by the SDS.’

He’s asked directly if the Home Office should have been told of the Scutt affair. He tries to manoeuvre around the question. Counsel does not let go, saying that given it was known in Special Branch that the secrecy and operational security of the SDS was a primary concern to the Home Office, surely they should have been notified.

Gunn caves and says once more that he was between a rock and a hard place, and made that judgement, though he doesn’t recall it. Again, he doesn’t think he would have changed the decision he made at the time.

At the end of the morning session, the Inquiry Chair, Sir John Mitting, intervened to ask questions. He had picked up on what Gunn said about details of the Scutt affair being detailed up to the Deputy Assistant Commissioner level and beyond. He wanted to know who he meant by ‘beyond’?

Gunn says depending on the seriousness and jeopardy it would have gone up the line of command in the Metropolitan Police. He cannot recall at all, but thinks in the circumstances it would have gone as high as the Commissioner, or very close to him.

Mitting notes that the Commissioner at the time was Sir Peter Imbert, prompting Gunn to state:

‘Ah, well, I would have thought almost certainly it would have gone to Sir Peter because he was a former Special Branch officer. He would have been trusted and understood the security of the operation of the SDS.’

Gunn probably didn’t realise how big a statement he just made, both on knowledge of issues in the SDS, but that there was corollary to his words, that Commissioners might not have been trusted. But that Special Branch men trusted one another to a degree that wasn’t extended to outsiders, even if they were their superior officers.

That is quite a position to have, demonstrating the sheer arrogance of Special Branch towards the rest of the Metropolitan Police, let alone the rest of the human race.

Spycops Methods

Eric Docker giving evidence at the Undercover Policing Inquiry, 28 January 2025

Following the Scutt affair, Gunn had asked HN39 Eric Docker, then the Detective Chief Inspector running the SDS, to conduct a review [MPS-0726998].

Docker’s report made a number of recommendations, among them was one for psychiatric testing of SDS candidates at the recruitment stage, and of former undercover officers as part of the post-SDS procedure.

Gunn says that was a sensible reaction to the Scutt affair, that he was trying to learn lessons and correct things.

In his reponse to Docker’s review [MPS-0726998], Gunn had expressed concern about the ‘necessarily long reins of supervision given to field officers’ and said they needed to be tightened. Counsel wants to know what the concern was here.

OVERSIGHT ISSUES

Gunn responds that normal undercover work was short-lived and focused on getting evidence to charge someone. The SDS deployments were different.

‘It was built upon the same – this is a point that’s not necessarily I think been understood by the Inquiry. Undercover policing is all about deception, deceit, intrigue. I am sorry, but that’s the reality of what undercover policing is.

When you have officers dealing with that, there is a sensitivity that they should understand the problems that they are going to face, which we tried in terms of management, but the SDS officers who were undercover were out on their own in the field, sometimes in dangerous circumstances, and their command was back in the office.

I thought at the time, was there some way we could put at management level or a supervision level to shorten the lines of communication between the poor – the undercover officers out there on their own in dangerous circumstances and the back office in respect of supervision.’

Gunn wanted closer links between the back office and the undercovers, not just for the officer’s welfare but also overseeing some of the behaviours:

‘I mean, these officers were out on their own and sadly some of them transgressed. That’s a matter of huge regret, but it happened. If there had been a closer supervision from the office to the field, it is possible we could have obviated the need for the distress that that caused.’

He adds that one shouldn’t expect someone who’s at the head of the organisation, as he was, to know all the details of the SDS’s operational activities. They inevitably had a lot on their plate. With a bit of buck passing, he reiterates that he relied on all the levels of the chain of command that stretched between him and the undercovers.

In a telling way, as he answers this point it’s clear he sees those undercovers as somehow victims in all this:

‘But the idea in that minute of closer supervision was to shorten the line of command between those in a difficult position and those in the office.’

This tightening of the leash never took place. Instead, as Gunn acknowledged in his witness statement, the intended level of senior oversight never materialised. He attributes that to a looser attitude towards supervision at that time, in the SDS chain of command and higher up.

THE VALUE OF THE SDS: THE REDS ARE STILL UNDER THE BED

Docker wrote at the time:

‘Officers of the Special Demonstration Squad are in a prime position to be able to report on any threat from London’s principal subversive groups and it is therefore essential that the SDS be allowed to continue its role as hitherto.’

Gunn agreed with that and had given no consideration to closing the unit down. In any case, such a decision would have involved the Commissioner, the Home Office and the Security Service.

Counsel drew attention to a 1988 MI5 briefing on the reduced threat from subversion. Gunn recalled it followed a change in the definition of subversion to the ‘Harris Definition’:

‘Those which threaten the safety or well-being of the State, and which are intended to undermine or overthrow Parliamentary democracy by political, industrial or violent means.’

MI5 took the view that they would not be so interested in public order issues in future. Special Branch command, including Gunn, took a wider, more pragmatic view of public order.

‘We did not accept that certain elements of the activity that caused public order wasn’t described as subversion.’

He then cites the current Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation, Jonathan Hall KC (Inquiry watchers may recall him as the barrister for the Metropolitan Police in 2017 and a keen proponent of anonymity for the undercovers) who recently said there should be a new law against subversion.

Gunn is passionate about this:

‘It is still a matter that was burning into our souls at the time that we were taking on, without necessarily the support or encouragement of the Security Service, on public order matters.’

DEAD CHILDREN’S IDENTITIES

Gunn says that the theft of dead children’s identities as the basis for undercover personae was a well established practice when he became Commander Ops.

Faith Mason and her son Neil Martin whose identity was stolen by officer HN122 while Gunn was in charge of Special Branch operations

He’s asked what he understood about the legal basis of this. He says the subject troubles him greatly, but then goes on a historical digression in order to demonstrate that Special Branch didn’t invent the tactic. They didn’t invent burglary or mugging either, but those would still be crimes if they committed them. A crime doesn’t become legal just because it’s committed by a police officer.

He understands the distress it would have caused the families had the information got out at the time, something that’s hard to justify.

Similarly, the current distress they have is, he says, a matter of personal regret for him. He acknowledges some of the evidence heard by the Inquiry from the families affected, calling it heartrending, and ‘that’s a great burden’.

Gunn could have stopped there, but he wants to defend the SDS. He says the practice was ‘necessary because we needed secure legends for our undercover officers’.

He points out that the decision to adopt this practice was made before his time, saying he believes that two or three undercovers using purely fictitious ‘legends’ had been compromised as a result. This method was judged to be better for for the interest and safety of the officers. Gunn makes it clear that he considers this to have been the right decision: ‘necessary operationally’.

Asked for more details about these compromised undercovers, Gunn says he can’t remember the details. He says he was aware it was part of the rationale that the use of birth certificates as officers had been compromised in the past.

There is no evidence to show these ‘two or three’ exposed officers existed. However, the fifth SDS officer to steal a dead child’s identity, HN297 Richard Clark ‘Rick Gibson’, was investigated by suspicious members of the group he’d infiltrated and confronted with ‘his’ death certificate. Despite this, the tactic continued for another 20 years, into Gunn’s time and well beyond.

Counsel points out that HN56 ‘Alan Nicholson’, an undercover deployed during his period as Commander Ops, had used a completely fictitious identity. Gunn says he can’t remember him.

Gunn isn’t stopping with that fictional excuse for identity theft. He adds that it was 40 years ago, without issues of computerisation. He marches on with his tone deaf defence, blaming the fact that this secret eventually got out as the real cause of the families’ pain.

‘And if I could just say, we did not believe with the secret nature of the work and the tactic, we did not believe that would ever get into the public domain. It didn’t get into the public domain from the SDS or the police. And I will leave the judgment as to how it got into the public domain for others to make.

But it was that that caused the stress, hurt and unhappiness of the poor families. Not our particular specific use of the tactic, although obviously the use exacerbated the problem.

But it was a very difficult and a very stressful time for officers and commanders and senior officers, and with the benefit of hindsight we would never use it again. We wouldn’t need to use it again. And I personally apologise to the families that were involved in that, because there were some heartrending cases.’

NO LEGAL BASIS

He’s asked what the legal basis for the tactic and he responds with one of the stand-out quotes of his already spectacular evidence:

‘Well, there was no legal basis for it, as I understood. And indeed there was no legal basis for a lot of the work we were doing…

We had no statutory backing for what we were doing until the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act, in 2000. We had no authority, legal authority, to have covert human intelligence sources until that Act. We were operating in a statutory vacuum.

We had very little statutory backing for what we did. It was fly by the seat of your pants and make judgements on difficult political operational decisions in everything we did.’

Gunn is on a roll, back where he wants to be, defending the brave SDS, constantly referring to them as ‘we’, as he identifies himself with them.

‘And, I think in 40 years of activity, I think we did that. We achieved – and this is another thing that I don’t think this Inquiry has fully covered – the importance of the work and the results that were achieved by our brave officers, who didn’t go off piste, who didn’t engage in sexual relationships, and that’s regrettable and should never have happened.

Where have we heard about all the excellent undercover operational work that took place for 40 years? Where have we heard that in this Inquiry?

I accept entirely that much of it is secret and will probably be held in camera, but that will never reach the public domain.

What the public have heard and will hear is the mistakes, the cock ups, the faults, the damages of the people who did wrong. And that’s wrong, and I take full responsibility as Commander Ops for whatever happened on my watch.’

Counsel notes his 2013 statement [MPS-0723255] to the Met’s own internal spycops investigation, Operation Herne, on the topic where he said:

‘I am not aware that the identities of dead children were used in creating the false identities and do not believe that to be so.’

After going off on one about Herne (see below), he claims that this was incorrect and he had said so at the time. In his written statement, he tries to explain this away by saying that to the best of his knowledge, he had never signed off on an application for a birth certificate of a dead child while he was Commander Ops.

Czechoslovakian spy Vaclav Jelinek, whose theft of a dead child’s identity was big news in 1977.

He tries to claim that his straightforward, unequivocal, total denial actually just meant he didn’t believe he answered any queries about it or approved any applications.

He doesn’t recall when he first learned of the tactic, but he can say it was not common knowledge in Special Branch. He accepts that as Commander Ops he could have ended the practice but the issue was never raised with him.

He is asked why he would need to wait for the issue to be raised with him.

He replies that it was considered operationally necessary, plus it hadn’t leaked into the public domain and caused any problems, so seemed the most suitable method. He says if the legality or propriety of it had been raised, he would have taken inquiries, but it wasn’t and hence it wasn’t a burning issue, and he never thought to question the legality of identity theft himself.

He accepts that with hindsight it would have been better had he taken a closer look, but can’t help having another dig at the Inquiry for having exposed the tactic.

NO ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Earlier Gunn had raised the case of Vaclav Jelinek, a Czechoslovakian spy who also stole an identity in this way.

Jelinek received wide publicity when he was exposed in 1977, and it caused huge distress to the family of the child whose identity he’d stolen. Why did that not give Gunn pause for thought to its moral and ethical implications?

As usual when he’s annoyed, Gunn employs Counsel’s name in a patronising way:

‘Well, as I have tried to explain, Ms Simcock, it was morally wrong. We shouldn’t necessarily have used that tactic in terms of the distress and hurt that it has caused, and I accept that entirely.

All I can say is in terms of the torrid period we were in, in the 1970s and 1980s and some of the 1990s, the security and safety of our officers undercover was of great importance.’

He says that judgement is supported by the fact that not only did everyone think the tactic would never would get out, but also that it shouldn’t have got out.

Counsel ask what might have happened if in the process of unmasking an undercover the tactic was discovered by activists. Was that consideration at the time?

‘Yes, it was a constant concern and the matter was continually considered as to whether or not the tactic should remain.’

The careful listener probably picked up on this inconsistency in his evidence. For someone who didn’t have involvement with SDS until he became Commander Ops, and said that he left all such matters to the Squad’s managers, Gunn betrays here and elsewhere a deeper role than he wants to let on.

Such a review of identity theft was because of its unethical nature and the Met would do everything in its power to keep it secret. If they could have done without it, they would have.

This is nonsense. In the early years of the SDS officers simply made up names. Then the tactic was described in spy thriller book and film The Day of The Jackal, after which SDS officers started doing it.

CHANGE TO CREATION

From the mid 1990s onwards, they reverted to making up names. They themselves proved they could do without it.

Gunn says that at the time it was an appropriate and necessary means to protect undercover officers:

‘We did take into account, I am absolutely certain, and I was at the time troubled if this ever got out it was going to be extremely embarrassing, not just for the police but for the Home Office and the Government. But it didn’t get out.

Now that’s not justification, I understand, for using it. But it is a consideration in terms of context and proportionality of the risk that we faced and how we deal with that risk.’

So the concern at the time was only for state actors, not for the bereaved families.

He reiterates his apology to the families. It is clear this topic troubles him a lot, but he cannot stop himself trying to square it with appeals to necessity and the belief it would never get out to the public. Even though it had done so, thanks to both the Jelinek case and The Day of the Jackal.

Our attention is taken to the 1990-1991 SDS Annual Report [MPS-0728958]. It noted that creating cover backgrounds became increasingly difficult as public records were computerised.

Was this not an opportunity to reconsider the necessity of the theft of dead children’s identities? Gunn says he would have seen the report, but was busy dealing with Irish and international terrorism. However, he accepts, with hindsight, that he should have acted on it.

He can’t say if he knew whether the Home Office was aware of the tactic. He says he doesn’t recall them being involved with the SDS while he was Commander Ops. He states that Home Office support of this tactic would have helped clarify the judgement of the officers who took the initial decision on the use of stolen identities. He says that given that the unit existed for 50 years, the Home Office must have been aware of these undercover operations.

He says he can’t confirm the exact degree of knowledge officers above him in the Metropolitan Police hierarchy had. However he finds it difficult to believe that they didn’t know about the spycops unit, particularly the ‘Assistant Commissioner Specialist Operations’.

HORRIBLE HERNE

Operation Herne is another bugbear of Gunn’s, and he is determined that the Inquiry will hear his views on it repeatedly. Herne was the Metropolitan Police’s own investigation into the spycop scandal, set up when the story first broke in 2011 and focusing on the SDS.

Counsel draws his attention to the statement he gave Herne in 2013 [MPS-0723255]. Gunn is glad she’s raised this as apparently Herne has been troubling him, and other officers involved in the Inquiry, ‘quite considerably’.

He points out that when they gave their interviews to Herne’s investigating officers, it was to provide them with a history of the unit, because they had no idea. It was done from memory, without looking at any documents, and they made ‘mistakes’. Gunn is very upset that the details have since been released into the public domain by the Inquiry.

‘They were notes of interviews that were never, ever signed by the officer who made them. That is wrong and I don’t believe it should have happened.’

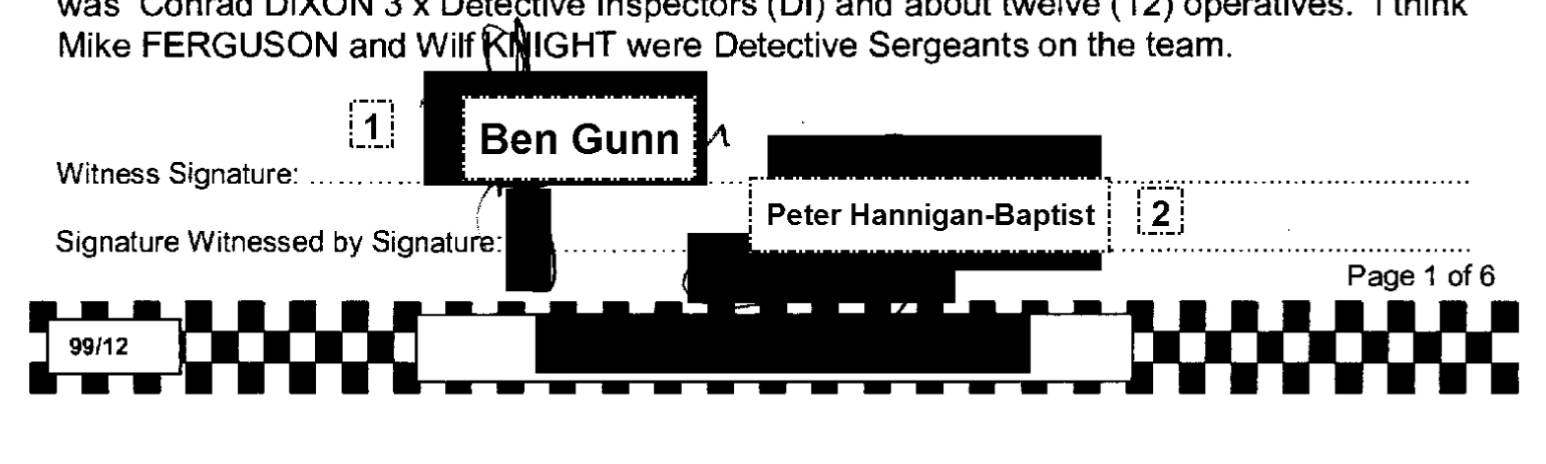

This is odd, as every page of his own Herne statement has a line at the bottom marked ‘witness signature’, and on each page it has been signed. He put his signature on it seven times. The Inquiry has redacted the signature but marked it as his.

One of seven instances of Gunn’s signature (redacted by the Inquiry) on his statement to Operation Herne. He told the Inquiry under oath that no officer ever signed their Herne statement.

He is not the first officer to be upset at the Herne statements being used in the Inquiry and made public.

It seems a lot of officers lied to Herne because they didn’t think anyone would check the plausibility and veracity of their claims, such as Gunn’s blanket denial of the theft of dead children’s identities.

Others went the other way and, in being interviewed by fellow police officers, were more frank and forthcoming than they’ve been at this Inquiry.

The Herne statements were, Gunn said, made for a different purpose and a different reason and not under caution. Counsel points out that he signed it with a statement of truth.

Later in the hearing he will bring this subject up again, referring to the statements (which he refers to as ‘unsigned notes’) and the outrage he feels about them appearing in the public domain thanks to the Inquiry.

Relationships

Another of Docker’s recommendations was:

‘Whenever possible, only married officers with a stable family background should be selected for SD duties. Although there should not be a total bar on the recruitment of single officers who may be deemed especially suitable.’

Gunn supported these recommendations at the time, and emphasised:

‘Only in wholly exceptional cases should single officers be considered, and then only after prior discussion with the candidate’s squad chief superintendent and Commander Ops.’

He doesn’t recall it.

Earlier, Counsel had pointed out that at the time of the Scutt affair, Gunn had stressed [MPS-740892] that:

‘There was a concern that the role of having an alter ego as an undercover became an easy excuse for any SDS officer to put forward whenever he experienced a professional/domestic problem.’

She asks about what sort of domestic problem such a defence would apply to.

Gunn explains that the undercovers were operating under extreme stress, but that it wasn’t really understood at the time:

‘They were living a lie. They were living a different world to their home life with their family, and we didn’t fully understand that, I am quite sure. It is a matter of regret, but it’s a fact of life 30, 40 years ago, I am afraid.’

He’s pressed about whether the reference to ‘domestic problem’ meant undercovers having sexual relationships outside marriage.

‘Yes, well, obviously. There was obviously a risk that any extra-marital sexual relationships of the undercover officers would affect their marriage. And taking into account the interests of the family was part of the process. But it probably didn’t — obviously didn’t work, because it wasn’t good.’

Pressed again whether it was an acknowledgement of the risk of deceitful sexual relations, he answers:

‘I don’t think it’s an acknowledgement. I think it’s an accepted risk.’

He didn’t explain what the difference was. Once again, the nuances that are apparent in Gunn’s mind are lost on the rest of us.

ANOTHER SPYCOP BOSS WHO DIDN’T KNOW

He claims that he wasn’t aware of any allegations of sexual relationships by undercovers at any time during his tenure as Commander Ops.

He says it was wrong and had he known it would hopefully have been stopped. He says ‘hopefully’ because he’d have had to take into account the circumstances.

‘And I apologise again, as everyone else seems to apologise, but I do it sincerely in respect of the sexual activity.’

But he wants to immediately add ‘context and proportionality’:

‘Nine or ten people allegedly transgressed in my period. What about all the dozens of other good, brave, intelligence-gathering undercover officers who didn’t go off piste, who didn’t go on a journey of their own and commit sexual offences. When have we heard about those?

All I am saying, Ms Simcock, is there is some balance that is not being drawn upon this and I want to put the context and balance, without in any way justifying the activity. Because it shouldn’t have happened.’

He is clear that when one of his chief superintendents was alleged to have known of a sexual relationship that officer should have told him. And likewise, that such knowledge should have been passed up the chain to him more generally. He is definitive that it was known to be wrong:

‘It is self-evident that that behaviour jeopardised the security and classification secret of that operation. The dangers that those officers exposed themselves to by that behaviour was paramount in terms of the whole exercise being revealed.

You don’t need police discipline regulations to know that unauthorised sexual activity in the job, when we were dealing with targets, is wrong, not right. They knew that. They must have known that.

But each one had circumstances which may or may not have put a different shade to it. I am not saying that. I am not suggesting that it justified the behaviour at all. But it should have come to the knowledge of Commander Ops.’

He is declaring the relationships to be wrong because of the operational problems they might cause for the spycops. There is, even this late on, still no consideration of the harm that was done to the women.

Counsel notes that Scutt had alleged that another undercover was having a sexual relationship, but the investigation of his claim was left to two SDS managers. And given all that had happened, they were unlikely to have believed him.

Spycop Bob Lambert deceived Belinda Harvey into a relationship during Gunn’s tenure as commander of Special Branch operations. Gunn says he had no idea about it.

Gunn’s answer is telling. He asks what the alternative would have been, asking if he was supposed ‘to bring in an outsider into the SDS to deal with matters that were highly secret’. For him it was proper to do the initial inquiry in-house, to see if there was anything behind this allegation. He doesn’t recall how this inquiry concluded.

It appears from contemporary documents that the undercover was exonerated. No action was taken.

However, Gunn accepts that this could have been because of the need to keep SDS operations secret. Such a decision would have to happen at commander level, but he doesn’t recall it coming to him.

Asked what he’d have done at the time, he says he would have considered all of the circumstances and sought the views of the SDS managers and line-managers. He would have made a judgement, ‘taking into account the wider issues involved, including reputation, security and all the other matters’.

It’s a non-answer with no actual action described, but given his earlier emphasis on the need to keep the SDS secret and avoid officers being disgruntled, it’s easy for us to imagine what he would have done.

SYMPATHY FOR ABUSERS

He’s taken to his Herne interview again (which he moans about some more). It gives an impression that he sympathised with the undercovers who entered into deceitful relationships:

‘I am conscious of the extreme pressures on the undercover officers and it may well be that, to maintain their deep cover, some officers may have engaged in sexual activity.’

Gunn disagrees, saying he didn’t sympathise, and repeats that this conduct was wrong and shouldn’t have happened. He does acknowledge that there was a risk of it happening, that had to be analysed alongside all the other risks.

He says his response would have depended on the circumstances. He claims that if the allegation was true, the undercover would likely have been removed from the field. Their continuing such a relationship could have risked not just their own cover, but the security of the entire spycops operation. Again, there is no mention that these officers were violating citizens they were supposed to protect.

Counsel points out that HN10 Bob Lambert and HN5 John Dines both had long-term sexual relationships on his watch. Gunn claims not to have been aware of this sexual activity at the time. Why does he say (in his witness statement) that he doesn’t consider this to be ‘a failure of oversight by senior managers’?

He accepts that, again with the benefit of hindsight, this issue should have been treated more seriously, but he wants to remake his point that the Inquiry is concentrating here just on the ‘miscreants who misbehaved’.

‘In terms of context and balance, all I can say is it is regrettable, seriously regrettable, that these officers went off piste and engaged in that behaviour. But there are so many others that did not, and I cannot emphasise that enough in terms of balance, proportionality and context.’

Counsel notes that Lambert disclosed his relationship to his manager, HN115 Tony Wait, at the time, and the latter took no action. Was that a failure of oversight?

Certainly, say Gunn. He adds that he should have been told at the time and would have done something. Counsel then asks how does he know that was an exception, as Gunn seems to rely on, rather than standard practice for managers?

Gunn admits he can’t be certain, but that doesn’t mean that senior managers would have known of the other relationships. He points out that the undercovers may not have all made such disclosures to their managers; after all they must have known these relationships were wrong. He claims to find it ‘distressing and almost unbelievable’ that he had no knowledge of this when he was in charge.

Later it is brought to his attention that, in his evidence, Wait said he reported Lambert’s relationship to his superior HN113 Ray Tucker. Gunn says he does not recall Tucker being associated with the SDS.

DECEIT, SUBTERFUGE, CONFUSION

In his written statement, Gunn states that the undercovers were aware that if such inappropriate sexual activity was discovered, the consequences could well be ‘career-ending’ for them. He says that this, combined with their skills in subterfuge, explains why they ensured that their managers didn’t discover these relationships.

Surely the managers should have overseen the deployments more closely, precisely because the undercovers had those skills in subterfuge?

‘Yes, well, I have already said, the whole essence of undercover work is based upon deceit, subterfuge, confusion. And it is quite clear that officers who had the skills and the ability to do that sort of work don’t grow on trees. But it is also quite clear that they all knew that they had to stay within the boundaries of the law.

But I have also explained, the boundaries of the law as far as SDS was concerned in the first 30 years of its operations were very sketchy. And you don’t need a law to say officers on duty shouldn’t engage in unwanted sexual behaviour.’

He accepts, though, that there was a risk. For him, this is yet another opportunity to make a point about how the Inquiry is failing to recognise how great the undercovers were for not commiting even more sexual misconduct!

Gunn is certain that the undercovers really suffered, repeatedly using words like ‘extreme’ to characterise their deployments. Bear in mind he’s largely talking about people leafleting McDonald’s and going to Socialist Workers Party meetings.

He does not excuse the officers who did engage in deceitful relationships, but he wants the other undercovers to be recognised for managing not to:

‘If you put a man and woman together in the circumstances that these officers were actually acting under, it was clearly a risk. These officers were going to squats, sleeping on mattresses, rooms full of individuals. The context of exactly what happened has not been properly discovered by this Inquiry, as far as I am concerned.

The circumstances – we put those officers in that position. We must take the responsibility for that. Not because they misbehaved – they should not have misbehaved – but we put them there and they behaved in the vast majority of cases properly, with integrity, with honesty and not a little bravery. And I don’t think that has been understood.’

In his statement, he says such relationships would have fallen under the definition of ‘disreputable conduct’. Does that not understate the seriousness of it?

‘Yes, it does. But let’s go to context again, Ms Simcock. I am trying to illustrate the boundaries within which managers’ and officers’ work within the SDS were very close to the limits of the law.’

The world was a different place back then, he reminds us.

MARRIED MEN ONLY

Counsel returns to the recommendations made in Docker’s report, especially the one about not deploying single men except in exceptional cases. Gunn agrees that the rationale for this was to mitigate the risk of sexual relationships, admitting that at the time, it was acknowledged as a risk that needed mitigation.

He agreed with Docker that a stable family background was an important anchor for the undercovers. Inappropriate sexual activity was not foremost in his mind but it was a consideration. It was not a priority for him. He says he had other concerns, especially in the aftermath of the Lockerbie bombing in December 1988.

Shouldn’t it have been acknowledged that some risk still existed, even if officers were in a supposedly stable relationship, such as marriage? Gunn claims this must have been considered, but agrees that they got it wrong.

He doesn’t recall any other action being taken to mitigate the risk of inappropriate relationships. He doesn’t think these could have been prevented by additional training, and says that any closer supervision would have meant undercover monitoring of the SDS undercovers.

Later on he’s asked whether he would have taken any steps to inform the woman being deceived, had he discovered such a relationship? He says that’s a difficult question, falling back to say that he would have needed to take all the circumstances into consideration first.

He says again that such relationships were wrong and shouldn’t have happened. He adds that he watched the recent TV show on the women affected, The Undercover Police Scandal: Love and Lies Exposed, and it was clear that the women were hurt, and this tugged at the heartstrings.

However, in their cases the relationships were not casual. He says the undercovers were certainly not directed to seduce the women in order to gather intelligence. It’s clear from how he says it, that for him there is a difference between a sexual encounter and a long-term affair.

Criminal Spycops

Every week, Gunn signed the diaries of the undercovers. He told Herne that the spycops’ accounts and expenses were strictly controlled. In testimony, Gunn says this was not unique to the SDS, it was ‘part of the general operational supervision in Special Branch’.

Every Friday, Branch officers submitted their diaries, which recorded what they had been up to, as well as their expenses claims. Usually it was signed off at Chief Superintendent (head of Squad) level, but for the SDS it went higher, to Gunn, because of the sensitivity involved. This was also done by Gunn’s predecessor as Commander Ops, Peter Phelan.

Could a more thorough examination of this kind of administrative paperwork have helped mitigate the risk of relationships and/or lead to their discovery? Gunn says it’s possible but notes that he had a lot of responsibilities:

‘And some of the matters you are raising in the cold light of day here – which are important and I don’t decry that – but actually they may pale into insignificance slightly when you’ve got a Lockerbie.’

ARRESTS OF UNDERCOVERS

Home Office Circular No. 35 from 1986 [MPS-0727412] sets out unequivocal rules:

‘The police must never commit themselves to a course which, whether to protect an informant or otherwise, will constrain them to mislead a court in any subsequent proceedings.

If his use in the way envisaged will or is likely to result in its being impossible to protect him without subsequently misleading the court, that must be regarded as a decisive reason for his not being used or not being protected.

The prosecution should be informed of the fact and of the part that the informant took in the commission of the offence.’

Gunn says he was aware of all this at the time. He says it applied to the SDS but that it was guidance only. He says there were only two undercovers who were arrested on his watch. One (HN4) was for drink-driving.

The other was HN5 John Dines, who was not only arrested in the 1990 Poll Tax riot but also wrote an article bragging about it.

In his written statement, Gunn said that as a starting point, the undercovers were supposed to avoid involvement in criminality, and anything beyond that was supposed to considered and authorised by managers.

Did that always apply, irrespective of the kind of group or activity the undercover was being deployed into?

Gunn responds more broadly:

‘Well, it was in part consideration of the circumstances involved in each incident. I had to make a judgement as Commander Ops as to whether or not the guidance was followed to the letter or whether the guidance was followed to the spirit.

On occasions I found myself between a rock and a hard place. John Dines was a classic example of a rock and a hard place, not so the previous drunk drive.

But I took the action I took in the best interests (1) justice, (2) the reputation and safety of the officer, (3) the reputation of the Metropolitan Police. And I had to make a judgement.’

IMMUNITY FOR SPYCOPS

He goes on to note that recent legislation – the Covert Human Intelligence Sources (Criminal Conduct) Act 2021 (aka the ‘spycops bill’) – recognises that undercovers could commit criminal offences for reasons of national security.

‘We never had that. But I had to do and take the spirit of the recognition that sometimes you are on the edge of the law.

And I was on the edge of the law but made that decision in the full cognisance of the guidance, my judgement against the circumstances of the time.’

The controversial law was opposed by many human rights advocates including Amnesty International, Reprieve, the Pat Finucane Centre, Privacy International and the Centre for the Administration of Justice.

Gunn says he was not aware of an acknowledgement within the SDS at the time that those targeting animal rights groups would inevitably need to participate in criminal activity.

He says he doesn’t recall any discussion with the Security Service about the difficulties of infiltrating the animal rights movement. Or the possibility that doing so might necessitate committing criminal offences, in order to gain acceptance from ‘hardened activists’.

He agrees though that this is highly likely, as animal extremists were seen as a much greater threat than many other target groups:

‘Not too many people remember the febrile atmosphere there was in this country at that time concerning animal extremism and the threat and risks that this country faced from those elements at the time.

They were extraordinary circumstances and we had to use extraordinary measures to deal with them. And animal extremism in respect of potential for criminal offences would have been top of the list.’

He rejects Counsel’s suggestion that perhaps there was an acknowledged risk that in such cases, the Home Office Circular’s directions wouldn’t necessarily be followed.

‘What I did was take into account the principles of the decision and the guidance, match it against the principles of the circumstances, and come to a judgement. And as I said: sometimes it’s a rock and a hard place.’

In his written statement, Gunn says he believed that the SDS had a process in place (to assess the involvement of undercovers in criminality) that appeared to work. Undercovers would inform the SDS if they were arrested and the managers would monitor the case as it went through the judicial system. They would report to the S Squad chief. Gunn says that as Commander Ops he would expect to also be made aware of the case.

He maintains that this process was entirely appropriate, even though it meant that the police got to decide what the courts were allowed to know. Gunn is not happy about such abuses of the judicial system being regarded today as ‘miscarriages of justice’:

‘As I have said, we were faced with circumstances that we had to deal with according to the law as it stood at that time – and I emphasise “at that time” – and the circumstances of the offence. And I go back to what I said earlier this morning about the need for security of the operation in respect of the Government, the Home Office and others.’

Essentially, he seems to be saying that if the law didn’t allow them to do what they wanted, then they’d ignore the law and do it anyway, because it was the law that was wrong.

TELL ME ABOUT IT

Gunn says he would expect to be informed of criminal activity carried out by an undercover even when it didn’t lead to their arrest. He cannot think of any offences or arrests Commander Ops should not have been told about, or any circumstances that would warrant not telling him.

In this, he includes criminal activity which the undercover was involved in, or on the periphery of, which led to the arrest of other people. He says he would expect to be informed of any charges or prosecution which followed, and if any undercover was expected to appear as a defence witness.

He states (in his witness statement) that if operationally necessary, it was acceptable for an undercover to commit minor offences, such as bill posting. However more serious offences were unacceptable.

When would it be considered ‘operationally necessary’? What would you have classed as ‘more serious’?

He says this means ‘offences which involved public safety, injury to others, serious criminal damage’, then, exhibiting another one of the nuanced differences that exist only in his head, adds: