New Spycops to Be Named But Still Hidden

The public inquiry into Britain’s political secret police has issued brief notes on applications for anonymity by another cluster of officers. As usual, these former spycops who invaded people’s lives want to have their true identities kept from their victims.

The Inquiry intends to release the cover names of most of them. After last week’s announcement concerning five officers whose real and cover names the Inquiry intends to keep secret, this is a bit of improvement. However there are still some fundamental flaws that undermine the Inquiry’s stated desire of uncovering the truth.

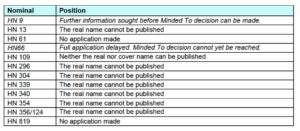

Known by their HN-numbers, there are 12 ex-spycops in the new list. The Inquiry is still looking into officers HN9 and HN66. Officers HN61 and HN819 are backroom staff, so there are no cover names involved, and presumably we will get their real and cover names.

As for the other eight, the Inquiry does not intend to release any of their real names, but wants to release the cover names of seven. They are all men. Here’s the rundown:

NEW NAMES COMING

HN13 is now dead. He was deployed 1974-78, thought to be infiltrating the Communist Party of England (Marxist-Leninist) though the name of the group may be wrong. He was prosecuted twice under his false name, one of these leading to conviction. His widow wants her husband’s memory left in peace. However, the police risk assessor thinks there is no chance of the cover name leading to the real name, so the Inquiry intends to release that.

HN109 is a mystery. Neither the real nor cover name will be made public and we cannot be told why. We just have to trust the veracity of what the police told the Inquiry.

The Undercover Research Group have done a characteristically meticulous job of cross-referencing the new information with what’s already known, and have found that HN109 was around the spying on Stephen Lawrence’s family.

The Inquiry’s Chair, John Mitting, has said getting definitive answers about spying on the Lawrences ‘is one of the central issues which the Inquiry must investigate’, yet he intends to keep this officer completely hidden.

HN296 infiltrated an unnamed left wing group from 1975-75.

HN304 infiltrated ‘a number of non-violent groups’ from 1976-79.

HN339 infiltrated two unspecified groups between 1970 and 1974.

HN340 was deployed against an unnamed group from 1969-72, and reported on others.

HN354 infiltrated an unspecified group 1976-79 and admits to ‘two fleeting relationships’ with women he spied on.

HN356/124. This one was accidentally given two numbers. Now dead, he infiltrated the Socialist Workers Party from 1977-81. He was on the April 1979 anti-racist demonstration in Southall where Blair Peach was killed by police.

NO NAMES, NO TRUTH

Time and again in the new list, the Inquiry says that publication of these officers’ cover names

‘may serve a purpose: to prompt former members of the group against which he was deployed to provide information about his deployment.’

Indeed, it is the only way those who were spied upon can be prompted to come forward. Without a cover name, an officer remains in the dark forever. This is why we are so insistent that all cover names be released.

We have no faith in the self-reporting of officers about their abuses, nor in their ex-colleagues who are carrying out the risk assessments on behalf of the police for the Inquiry. Any public servant should be publicly accountable, let alone one from a covert institution guilty of so many serious abuses that it needed a public inquiry into its misdeeds.

Even those who still find the Met a trustworthy body must accept that the spycops units have no credibility left. Since the scandal broke we have been subjected to a flurry of desperate lies from everyone involved, from the officers themselves right to the top ranks. As one lie gets exposed, they change their story until that, too, falls under the weight of new evidence. So the more they want to hide an officer, the more suspicious the public becomes.

POLICE PERJURY

The Inquiry has said that people who were deceived into sexual relationships by officers deserve the fullest answers, and it will be seen as a reason to release an officer’s real name as well as the cover name. They appear to take a less stringent approach to officers who deceived the judicial system and orchestrated miscarriages of justice.

The one in the new list, HN13, was far from the only spycop to be arrested. The five spycops the Inquiry spoke of two weeks ago – and whose real and cover identities the Inquiry intends to withhold – included two who admit being arrested whilst undercover, one of whom was prosecuted under their false identity.

There is plenty of evidence that this was common practice throughout the era of the spycops units. When they were arrested alongside people who were convicted, it means their evidence was withheld from the court and the conviction is unsafe.

Undercover officer Mark Kennedy was arrested and involved in cases that led to 49 wrongful convictions that have now been quashed due to his exposure by activists. The detail of his actions also made it clear that the police and Crown Prosecution Service colluded to orchestrate these miscarriages of justice.

Mark Ellison QC’s 2015 report into the issue found many more among the Special Demonstration Squad’s remaining records.

‘Using the SDS Annual Reports it has now been possible to identify 26 SDS officers who were arrested on a total of 53 occasions.’

That’s just what can be deduced from the SDS annual reports. The true total is likely to be higher. It’s notable that Mark Kennedy was from another unit entirely, the National Public Order Intelligence Unit, and other officers there, such as as Rod Richardson and Lynn Watson, were repeatedly arrested as well.

All of this contravened strict instructions from the Home Office that officers should be withdrawn if they risked misleading a court.

In 1969, the year after the Special Demonstration Squad was set up, the Home Office issued Circular 97/1969, and it was clear and unequivocal.

‘The police must never commit themselves to a course which, whether to protect an informant or otherwise, will constrain them to mislead a court in subsequent proceedings. This must always be regarded as a prime consideration when deciding whether, and in what manner, an informant may be used and how far, if at all, he is allowed to take part in an offence.

‘If his use in the way envisaged will, or is likely to result in its being impossible to protect him without subsequently misleading the court, that must be regarded as a decisive reason for his not being so used or not being protected.’

The officers cannot feign ignorance. They knew the gravity of the situation and they chose to lie.

Either courts were told it was an agent – meaning it was an unfair trial for other defendants – or else this was perverting the course of justice and perjury. The Inquiry and the wider public should treat this as a negation of police duty and an affront to justice.