UCPI: Weekly Report 5: 26-30 April 2021

This is the second of our weekly reports on the current round of Undercover Policing Inquiry hearings examining the actions of the Metropolitan Police’s undercover political unit, the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS), from 1973-82.

This is the second of our weekly reports on the current round of Undercover Policing Inquiry hearings examining the actions of the Metropolitan Police’s undercover political unit, the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS), from 1973-82.

These hearings are scheduled to run for four weeks before taking a break for about a year. Subsequent hearings will look at the unit’s later years.

This report summarises the main points of the second week of this set of hearings. For more details, see our daily reports linked from our Inquiry page. For background information on the Inquiry, see our UCPI FAQ.

WHAT’S NEW THIS WEEK

Following last week’s opening statements, the focus this week was on witnesses from both the undercover unit the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) and the ‘non-state core participants’ (ie the people spied on) in the era in question.

Many of the same themes emerged as during the first round of hearings in November 2020, which looked at the SDS from its foundation in 1968 until 1972. Further evidence has done nothing to contradict the impression of the SDS as a secret and secretive unit with a remit to report every detail of the lives of the people they spied on.

‘BY ANY MEANS NECESSARY’

Spycops picked their own targets, or were assigned them by the Security Service (aka MI5). Miscarriages of justice would be authorised in order to prevent the unit being exposed. The foundations laid in the early days of the SDS were rapidly built upon during 1973–82, eventually resulting in the credo revealed by whistle-blower officer Peter Francis – ‘by any means necessary’.

And yet, the information obtained by those means was characterised by some spycops this week as being of little use; the groups they went to such lengths to infiltrate as basically harmless. Other undercovers fell back on the refrain that they reported everything and left it to their superiors to filter out what was useful. Both spycops were simply pulled out without strategy.

This doesn’t explain why some reports contained passing remarks made by individual activists that had been deliberately exaggerated, or even invented, so that the groups would seem dangerous or in favour of violence.

In this report we highlight some of the week’s events as examples of recurring themes, and look at the infiltration of various anti-apartheid campaigns. Full coverage can be found in our daily reports.

LITTLE TO NO TRAINING

‘Dave Robertson‘ (HN45, 1970-73) and ‘Alex Sloan‘ (HN347, 1971) – who both gave evidence on 27 April – spoke of having little to no training for their roles, and being expected to pick it up – or just make it up – as they went along.

It seems that the higher-ups were doing the same thing. A statement from spycop ‘David Hughes’ (HN299/342, 1971-76) details how SDS management did not really know what to do when another officer was suspected of, or in the case of Robertson, identified as being undercover by the people they were spying on.

Alex Sloan explained that he was not given any guidance about what to do if his cover was blown. He was never instructed on what to do if offered a responsible position like treasurer or secretary in a target group (but thought he should accept it). He was not told about ‘legal professional privilege’, a long-established legal convention prohibiting his presence at discussions between lawyers and their clients. This last point came up more than once this week.

In most cases, the spycops themselves chose which people to spy on and which groups to infiltrate. David Hughes attended public meetings advertised in then-radical magazine Time Out. As we saw last week, none of these groups (bar one) was right-wing.

Special Branch’s remit, and by extension the remit of the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS), was to deal with ‘subversion’ (opposition to the UK’s parliamentary democracy), and threats to public order. From the evidence this week, the spycops were not given clear criteria on how to assess what was subversive.

Robertson could not recall guidance about what might constitute ‘extremism’ or ‘subversion’. He said vaguely ‘it was just part and parcel of the whole’. Alex Sloan, when asked if he knew what was subversive, replied that it wasn’t for him to judge – another recurring standpoint of the spycops.

Rajiv Menon QC, representing Piers Corbyn, defined it as activity that:

‘threatened the safety or well-being of the State and was intended to undermine or overthrow parliament by political or industrial means’.

Two justifications for spying on non-subversive, non-violent, law-abiding groups emerged: a) they might lead to violent groups b) it was useful to confirm that they were indeed what they seemed to be. Neither of these justifications seem to have been borne out by the results of decades of spying.

It is now clear that both Special Branch and the SDS spycops have always had a broader remit, which extended to threats to police credibility, corporate profit, and the convenience of the government of the day.

The campaigns infiltrated were all what we would now describe as social justice groups. The one exception – as mentioned before – was when a spycop was asked to infiltrate a right-wing group by the left-wing group he was spying on.

LITTLE TO NO USE

Once the spycops were embedded in these groups, their initiative appears to have deserted them.

Another repeating theme is the spycops themselves reporting that the groups were no real threat, and / or giving evidence now that the intelligence they gathered was basically useless. Descriptions given in evidence included:

- ‘Mickey Mouse’, ‘never scary at all’, not causing ‘aggravation to anyone’, (Alex Sloan on the Irish National Liberation Solidarity Front);

- ‘The majority of people I encountered during my deployment were not that extreme’ (David Hughes)

- ‘I do not think my work really yielded any good intelligence’ (Sandra Davies)

And yet, rather than withdrawing and trying to find a group that was bent on public disorder (such as Column 88, Nazis who were using firebombs), they continued to report on the peaceful groups working for positive social change.

UNFILTERED ‘INTELLIGENCE’

Nor were they directed to filter what ‘intelligence’ they gathered – every detail went into the reports, from activists’ body types to cigarette brands. Robertson said that ‘everything was fair game for reporting’, including details of flowers given to speakers. It was someone else’s job to decide what to do with the intelligence he collected.

The spycops reported highly personal information, such as the condition of Ernest Rodker’s health and the birth of his child. Some would give their own slant to their reports. Hughes stated:

‘Sometimes my personal views crept into my reporting. The SDS office never told me this was inappropriate or not permitted.’

They reported ideas from activists that were what executives now would define as ‘blue-skying’, involving fireworks, ticker-tape, and weather balloons, as though they were serious plans – despite the groups having no history of such actions.

Christabel Gurney

They reported on Christmas parties. One held as a fundraiser for the Anti-Apartheid Movement in the home of Christabel Gurney was 75p a ticket, 12p for drinks, and attended by a spycop. Sandra Davies seems to think that festive cakes and sweets made by the Women’s Liberation Front at the request of the Black Unity and Freedom Party were a ruse to ‘get their philosophy across’ to children.

Many of the reports went to MI5. Some fifty years later, MI5 still has them. Dave Robertson talked about not typing up his own reports after writing them, but knowing they were routinely copied to MI5. He said it was ‘obviously pretty routine’ that MI5 would request details about someone and the SDS would supply them.

This week Piers Corbyn, Diane Langford, and Ernest Rodker all specifically asked that their files be withdrawn and handed over to them. They are by no means the only activists who want this. It has always been one of the core demands of COPS.

A CULTURE OF DUBIOUS PRACTICES

We heard from various spycops this week, some in person and some via written statement. Despite – or because of – some convenient bouts of amnesia, their reports are consistently similar, and not just for this period (1973 – 82). They clearly indicate a culture of dubious practices that began with the very start of the undercover units and intensified, fostered by a climate of complicity, as the years passed.

All of their statements uphold the fact that knowledge of SDS activity went all the way to the top of the command chain. Hughes recalled the then-Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, Robert Mark, visiting the unit:

‘It was obvious to me that he had concerns about the SDS. I remember words to the effect that “you realise that you could cause me tremendous problems under certain circumstances”.’

The motivation for the miscarriages of justice resulting from spycops violating lawyer-client privilege and standing trial under cover names, as demonstrated this week by ‘Michael Scott’ (HN298, 1971-76), was clear from the very beginning.

Scott was arrested as part of an anti-apartheid action. To avoid revealing the existence of the SDS, he was instructed to stand trial under his cover identity, including deliberately lying from the moment he took the witness stand. He was to attend meetings with genuine activists and their lawyer – violating lawyer-client privilege; and to withhold evidence that would have exonerated the activists (the protest took place on private land – a pub car park – and did not, as claimed, block a public highway).

Scott received a conviction – or rather, as he had chosen to steal the identity of a living person, the real Michael Scott did. The police reports show no concern at all about deceiving the court and orchestrating a miscarriage of justice, purely to avoid any ‘potential embarrassment to police’ if it became known that a spycop was involved.

Rodker sees this as part of a repeating pattern:

‘The failure to view activists as individuals with their own legitimate rights and interests, and the decision to place those second to the unfettered gathering of information on them may be a precursor to some of the more gross abuses of activists that, I note, happened in later periods of undercover policing of campaigners.’

Judge Mitting has said he will turn this matter over to the Inquiry’s panel that is due to review likely miscarriages of justice. The Inquiry has known about these miscarriages for years now, and in light of the age and health of the activists whose convictions may now need overturned, it is shocking that this Panel has still not been set up by Mitting.

IN CONTEXT

During the first week of the hearings, the police lawyers stressed the importance of looking at the activities of spycops in context, rather than through a modern lens. It was a different time with different values. A time when it was apparently fine to include in reports that: an activist couple had ‘a Mongol child’; ‘large Jewish nose[s]’, or the fact that a woman activist didn’t wear a bra, as merely objective descriptions.

It is true that the activism under discussion should be fully understood in the context of what it was trying to achieve. To properly assess the impact on the groups they infiltrated, one must know what causes the spycops were undermining.

WOMEN’S RIGHTS

Diane Langford co-founded the Women’s Liberation Front in 1970. At this time women could not get a mortgage, credit card or loan without a male co-guarantor. They did not have the right to equal pay or maternity leave, and could be fired for becoming pregnant. They had no legal recourse against discrimination in employment, education, and training. Contraception was not available on the NHS; there were no rape crisis centres. It is indefensible to say that this is a status quo that should have been maintained.

However, as spycop ‘Sandra Davies’ (HN348) told the Inquiry in November:

‘Women’s liberation was viewed as a worrying trend at the time.’.

The aims of the WLF – equal rights for women and a society free from all forms of discrimination – were clearly and publicly stated in the application for membership, which Sandra Davis would have signed when she infiltrated the group in 1971. Their methods were also clear and public: demonstrations, open meetings, street theatre, film screenings, boycotts, and other collaborative actions. Diane Langford stressed the importance placed on collective action over individuals ‘indulg[ing] in macho posturing’.

Diane Langford, New York City, 1996

‘Dave Robertson‘ (HN45, 1970-73) reported on the WLF, and several other groups that Langford belonged to, including the Revolutionary Marxist-Leninist League (RMLL) which she formed with her late husband and fellow activist Abhimanyu Manchanda. A small group focused on studying deep political theory, the RMLL aimed to guide and advise the WLF and other groups campaigning against oppression.

When the RMLL eventually suspended Manchanda, splitting that group and destabilising two others, Robertson would play a part or even had a vote in that decision. When the WLF ousted Langford, leading it to change its name and then fall apart, Sandra Davis voted against her (and was elected treasurer shortly after).

As with Richard Clark (‘Rick Gibson’ HN297, 1974-76) last week, we see spycops deliberately taking positions of influence within the groups they infiltrated and then using this to weaken them – and bring about their demise.

There is a deeply unfunny irony in that Sandra Davis was working to delay equal rights for women on 10% less pay than her male colleagues. It is also worth noting that despite police lawyer David Perry QC (in Kate Wilson’s case) attempting to deny a culture of sexism in the SDS, this is the era in which the unit developed and consolidated the methods and practices that it would use for the next thirty years.

ANTI-APARTHEID CAMPAIGNS

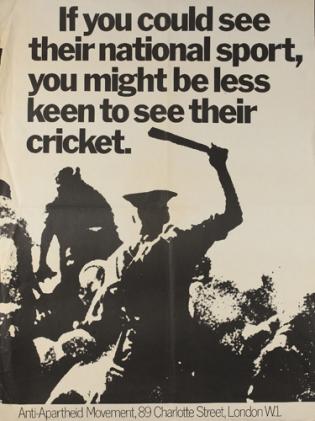

Not content with preserving sexism, the SDS was also deeply suspicious of any group that sought to end racism. Again, to look at their operations in the context of the times is to see violent right-wing and fascist groups on the rise in the UK, and a government cheerfully doing business with South Africa’s apartheid regime.

Apartheid was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 until the early 1990s. It categorised people into a hierarchy of racial groups, with whites at the top.

‘Beach and sea whites only’ sign, apartheid South Africa

The laws segregated all areas of life, reserving the best for whites. It affected everything from education, employment and housing to which bench people could sit on or which beach they could visit. Most of the population was denied the right to vote. Sexual relationships and marriages between people of different racial groups were illegal.

Groups fighting against apartheid in the UK were infiltrated by Mike Ferguson (HN135), ‘Michael Scott’ (HN298, 1971-76), HN332, Jill Mosdell (HN346, 1970-73), and Douglas Edwards (HN326, 1968-70).

THE ANTI-APARTHEID MOVEMENT

The Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM) was set up to unite as many people as possible with the same goal: bringing equality and democracy to South Africa. As a UK group, they focused on the UK institutions and companies that were trading with and supporting the South African government, and attempted to stop these practices.

Anti-Apartheid Movement demonstration, London, 15 July 1973

Central to the AAM’s approach was to try and avoid doing anything that would distract the press from the real issue – the violence of the South African apartheid regime. As such it eschewed violence or heated confrontation. Rather, it concerned itself which included common campaign tactics such as organising petitions, public meetings, pickets, vigils, cultural events, and mass rallies.

In 1970, the AAM President was the Rt Rev Ambrose Reeves, an Anglican bishop. Vice presidents were Sir Dingle Foot QC MP; Rt Rev Trevor Huddleston, another Anglican bishop and Rt Hon Jeremy Thorpe MP. Also on the board was the then-leader of the Liberal Party Basil Davidson, an historian who had worked for MI6 behind enemy lines in the Second World War and been awarded the Military Cross.

This is hardly a group of radical subversives; far from overthrowing parliamentary democracy, the AAM’s sole aim was to extend it to southern African nations that were subjected to racist rule of colonial white minorities.

Despite this, the AAM was infiltrated by the SDS.

STOP THE SEVENTY TOUR

While the AAM resorted to mainstream methods, younger people wanted to do more. This is how the Stop The Seventy Tour (STST) was born, its immediate and principal aim was to stop the white-only South African cricket team from touring in the UK in the summer of 1970. More broadly, its aim was to make a very strong political point that people representing apartheid were not welcome in the UK.

While the AAM resorted to mainstream methods, younger people wanted to do more. This is how the Stop The Seventy Tour (STST) was born, its immediate and principal aim was to stop the white-only South African cricket team from touring in the UK in the summer of 1970. More broadly, its aim was to make a very strong political point that people representing apartheid were not welcome in the UK.

STST used all classic forms of non-violent direct action (NVDA), pitch invasions being the most prominent. They sought to follow the well known principles of civil disobedience learned from recent history such as the struggles for Indian independence by Mahatma Gandhi and for black civil rights by Dr Martin Luther King.

They would run on to cricket pitches and sit down. Painting slogans on the walls outside Lords cricket ground, and even these were things like ‘stop the tour’ and ‘go home’ rather than anything more profane or aggressive.

According to Prof Jonathan Rosenhead (non-state core participant):

‘Stop The Seventy Tour was a nice floppy liberal alternative organisation, which many people could join. There was no party line and no ‘militancy’ as such, and the only thing everyone agreed on was the need to end apartheid.’

Yet the STST was infiltrated by the SDS.

SPECIAL ACTION GROUP

A small group of anti-apartheid activists believed in direct action and organised in private to add an extra layer to the campaign – calling themselves the Special Action Group (SAG). Rosenhead, who took part in the SAG, refuted the suggestion of the Inquiry calling them ‘the covert arm’ of the Stop the Seventy Tour, saying they just wanted the element of surprise.

For instance, one of them would check into the hotel where the rugby team stayed, overhearing their room numbers to either glue their locks, or write a message on their bathroom mirror with shaving cream At a certain point the team just wanted to go home.

The SAG was infiltrated as well.

DAMBUSTERS MOBILISING COMMITTEE

The Dambusters Mobilising Committee (DMC) was a coalition of groups including the AAM, that opposed the construction of the vast Cabora Bassa dam project in Mozambique.

The dam was a collaboration between South Africa, Rhodesia and Mozambique’s colonial ruler Portugal. It displaced local people without compensation in order to supply electricity to apartheid South Africa, and undermined United Nations sanctions.

The DMC campaigned to dissuade British (and other European) companies from financing or otherwise becoming involved in the Cabora Bassa project.

DMC meetings were small, attended only by representatives of the organisations in the coalition. They spent a lot of time researching companies involved in the dam. Some campaigners bought shares so they could attend Annual General Meetings of various companies, such as that of Barclay’s Bank who were guarantors of some of the dam’s financing, and pose pertinent questions to the meeting.

Even this Coalition was reported on.

MCCARTHYIST QUESTIONING

There was something both incongruous as well as slightly offensive in the line of questioning pursued by the inquiry throughout the week, repeatedly pushing to imply STST activists were violent and attempting to demonise their actions.

This is especially galling given the murderous racist violence of the South African apartheid regime they were protesting against. Adding to this, that within the UK it was STST protesters who were routinely assaulted by the police, stewards and some rugby supporters.

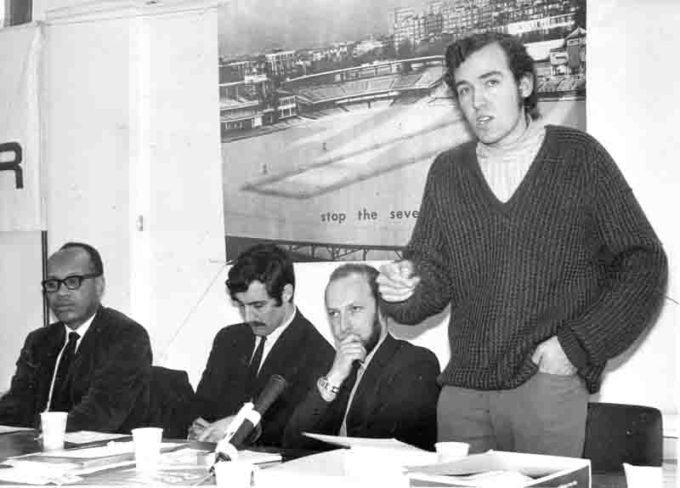

Peter Hain at a press conference called by the Stop the Seventy Tour (STST) campaign, 7 March 1970. Left to right: Jeff Crawford (Secretary of the West Indian Standing Conference) England cricketer Mike Brearley, STST member Mike Craft, & STST Chair Peter Hain.

On the final day of the week, the Undercover Policing Inquiry was devoted to hearing evidence from just one person, Lord Peter Hain. He had a rich career as an activist, and hence a thick secret police file that include decades of reports from undercover officers of the SDS

Hain founded and chaired the STST campaign, from its launch in September 1969 until it was disbanded in late May 1970.

Hain refused to be put in a position where, as an activist, he had to defend his campaigning, telling the Inquiry this attitude put both them and the police at the wrong side of history.

Like earlier in the week, the Inquiry opted for a line of questioning reminiscent of the McCarthy Un-American Hearings of the 1950s, in which guilt by association with radical groups or ideas is seemingly used to justify the State’s spying.

Their first question was whether Peter Hain’s parents, who had fled South Africa, were ‘communists’, when it is well known they were active members of the Liberal Party.

WASTE OF POLICE MONEY

Asked if it was understandable that police ‘faced with these novel, rather effective tactics’ should seek to gather all the information they could on campaigners’ secret plans, Hain cut in:

‘I know what you’re trying to insinuate, but… we were transparently public, some might say unwisely honest, about what our intentions were, which was to stop the tour by non-violent direct action.’

Hain made the point that the Anti-Apartheid Movement suffered extreme violence from agents of the South African State in London. This included the bombing and arson attacks on their offices, letter bombs being sent to their homes. Hain himself was sent one – it was opened by his teenage sister, and the matter was never fully investigated by the police. Hain demanded to know why this was.

Hain put it to the Inquiry that the SDS was a completely disproportionate waste of police resources: ‘

Why were they not targeting the agents of apartheid bombing and killing and acting illegally and violently in London at the time?’

In response to the Inquiry’s repeated suggestions that the STST took risks with their actions, that could have led to violence, Hain insisted that the main violence came from the other side. He described the brutal response to a pitch invasion at the Springboks’ match in Swansea in November 1969:

‘They ran on, they sat down, they interrupted play for, as I recall, over ten minutes, as it was intended. They were then carried off by the police and thrown to rugby stewards, rugby vigilantes, if you like, recruited for these purposes, and thoroughly beaten up. A friend of mine had his jaw broken, a young woman demonstrator nearly lost an eye…

‘They could have been carried out of St Helens, but there was clearly a pre-planned attempt to beat the hell out of the protesters, and that’s what happened.’

‘SOUTH AFRICAN TERRORIST’

The mindset and political framework of the undercover policing units seems not to have changed over the years.

A police report from 1993 – as the apartheid regime was collapsing and Nelson Mandela, three years out of prison, was poised to become president – refers to the Anti -Apartheid Movement as ‘Stalinist-controlled’. If that is the type of thinking of these units, Hain said:

‘we have a particular ideology of undercover policing which frankly cannot be defended.’

He has also learned recently, from a document revealed last month in Kate Wilson’s case in the Investigatory Powers Tribunal, that in November 2003 he was described as a ‘South African terrorist’ by undercover police officer Mark Kennedy.

Kennedy was in the National Public Order Intelligence Unit, a parallel unit to the SDS, and deceived Kate (and other environmental campaigners) into a relationship.

At the time this spycop was calling him a terrorist, Hain was was a member of the British Cabinet, Secretary of State for Wales, the leader of the House of Commons and the Lord Privy Seal.

Hain retorted with a with a question that summarises the hearings of this week effectively:

‘What is it in the DNA of undercover policing that allows its officers to get such a biased and reactionary view of the world, that they make these kind of biased and completely unrepresentative and libellous and defamatory statements?’

<<Previous UCPI Weekly Report (21-23 Apr 2021)<<

>>Next UCPI Weekly Report (4-7 May 2021)>>