UCPI Daily Report, 18 Nov 2020

Tranche 1, Phase 1, Day 13

18 November 2020

Evidence from:

Officer HN348 aka ‘Sandra Davies’

The penultimate day of the Undercover Policing Inquiry’s first phase was scheduled to have two people appear.

Helen Steel, a lifelong environmental and social justice activist who was in numerous spied-upon groups and was deceived into a relationship by undercover officer John Dines, was due to deliver her opening statement. However, she was unable to do so.

The rest of the day was given over to evidence from Special Demonstration Squad officer HN348, which seemed something of an odd proposition, given that she appeared to have had about as minor a deployment as is possible for a spycop – long ago, not for long, deployed into one group that doesn’t appear to have warranted spying on even by the police’s standards.

As it turned out, this was the point; her testimony demonstrated the lack of guidance given to officers, and the seemingly total absence of any consideration of the impact of this intrusion on the lives of those targeted.

She infiltrated the Women’s Liberation Front for about two years, 1971-73, using the name ‘Sandra Davies’. A small feminist group with Maoist leanings, its meetings were attended by about 12 people, hosted at one of the member’s homes.

’Davies’ was a full-time spy on them for two years, producing no intelligence of any value, and would have stayed longer if she hadn’t been compromised by another officer. It’s the generalised, hoover-up approach to information gathering, checking on people who pose no threat.

PRIDE OR SHAME?

Davies has been granted anonymity by the Inquiry despite being assessed as having a low risk of any kind of reprisal. In her ‘impact statement’, she said that she wanted anonymity because she would be embarrassed if the group’s main activist found out the truth. She also said her reputation would be tainted if her friends found out she had been a spycop.

It’s an extraordinary display of mental gymnastics – when we question the purpose of spycops, police tell us that they’re doing vital & noble work ensuring the safety of everyone, yet when we question why they want anonymity, they say it would be humiliating to be known as one.

This feat is matched by the idea that although the spycops used the Stasi principle of gathering all information on anyone close to political activity, with the expectation that some of them might turn out to be a problem at some point in the future, this was necessary to protect us from having to live in a repressive Stasi-like State.

MAXINE PEAKE IS A SPYCOP

As the Inquiry persists with the idea that a glitchy live transcript is adequate public access – denying the feel of the witness’ evidence, causing eyestrain for viewers and excluding anyone visually impaired – Police Spies Out of Lives once again provided a read-along on their YouTube channel.

Today, guest star Maxine Peake read the words of ’Sandra Davies’.

The read-along’s popularity exceeded the Inquiry’s own ‘viewing’ figures.

There will be another read-along, of HN345‘s evidence, on Thursday 19 November, starting at 11:30.

SANDRA DAVIES WAS ALSO A SPYCOP

HN348 made a written statement to the Inquiry last October.

She recalled using the cover name ‘Sandra’, and having seen some documents listing members of the Women’s Liberation Front that name ‘Sandra Davies’, she conceded this may well have been her. The evidence – which we’ll come to a bit later – seems conclusive, yet she still wouldn’t completely confirm it was her.

It set a pattern for the afternoon, of the documents showing things, and her saying that she was unable to recall anything beyond what the documents showed.

In this report, we’ll call her Davies for ease of reading.

JOINING THE SPYCOPS

Davies was vetted before joining the police, and joined Special Branch in January 1971, having passed an exam and several interviews. She didn’t have any undercover experience before being asked to join the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS), and it appears that she did this remarkably quickly – by mid-February.

She was asked if this meant there were only 3-4 weeks before she was recruited into the SDS, She said she couldn’t remember, but thought it was longer, perhaps a few months. However, her first SDS report is dated 17 February 1971.

She explained her motivations for joining Special Branch – these included her career development within the police, which she viewed as a long-term career.

RECRUITED BY HIGH-FLIER IMBERT

Until she was approached by Peter Imbert (who later became Commissioner), she had never heard of the SDS. He was the one who asked her to join, and explained that her job would be to ‘collect and disseminate information about anti-social behaviour’. She understood that intelligence was needed to prevent the police being unprepared for serious public order situations like the demonstration against the Vietnam War in March 1968.

Imbert will not be giving evidence at all, as he is one of the three Metropolitan Police Commissioners who have died since the Inquiry was announced. Between them, Imbert, David McNee, and Kenneth Newman ran the Met from 1977 to 1992. More than that, as Imbert’s recruitment of Davies to the SDS shows, they will have had a lot of relevant knowledge from the time before they became Commissioner.

It’s not enough to know what the officers did. We need to know who authorised and sanctioned these operations. The loss of testimony from those Commissioners, who were ultimately in charge of the SDS for a third of its existence, is one of the effects of the colossal delays the police have inflicted on the Inquiry process.

TRAINING? WHAT TRAINING?

Apart from being advised to keep a ‘low profile’, Davies was given very little training or guidance. She didn’t know how long she would be deployed for. She doesn’t remember any ‘home visit’ from a senior officer.

Asked why she was recruited, she said:

‘perhaps they were just looking for a woman, and in those days there weren’t that many of us! Perhaps there was nobody else.’

The SDS’ annual report of 1971 [MPS-0728971] said:

‘The arrival of a second woman officer has added considerably to the squad’s flexibility and has proved invaluable in the comparatively recent field of women’s liberation.’

The other woman was Jill Mosdell – Sandra confirmed that she knew Mosdell well and they became good friends. Mosdell was deployed into the Anti-Apartheid Movement from 1970-73.

DEPLOYMENT

She described her preparation for going undercover as taking off her wedding ring and make-up, finding a cover address (a shared house in Paddington to which she went only occasionally) and being ready to tell people she was a student at Goldsmiths if they asked (they never did).

She said that she would go to meetings and other events, then a day or two later visit one of the two SDS ‘safe houses’, where she would draft a report. This would then be discussed with her manager, amended, and sent for typing up.

She attended the safe house most days, and would talk to the other officers there, though, she claims, not in any detail about their deployments.

She didn’t have any experience of writing such reports beforehand, and was given little in the way of guidance. Her approach was to report anything she observed. According to her, the spycops were ‘building up a picture of the people who were involved in these various groups’.

PERSONAL INTRUSION

Davies was shown a report she’d made [UCPI0000026387] in August 1971, about a member of the Women’s Liberation Front (WLF) and the North London Alliance in Defence of Workers’ Rights (LADWR) travelling to Albania on holiday. The activist’s photo was attached to the report.

Asked why she’d felt that degree of personal information was necessary, she replied that it might be:

‘to do with the bookshop in North London, and the links with other extreme groups associated with that bookshop’

She said that the Women’s Liberation Front merited investigation by the spycops because ‘of the way they were expressing themselves, and their links’ to other groups of interest.

Most of her reports concern her attending regular meetings, often in people’s homes.

Was she ever given guidance about balancing people’s privacy vs what was needed for ‘effective policing’ – for example was she given guidance about entering people’s homes?

She was told that her job was to “be an observer, not a participant”, that she should avoid being an ‘agent provocateur’ but stick to recording what was said in the meetings she attended.

Her supervisor would accept her hand-written report, she said she didn’t always see the typed version; neither did she know who typed it or where it went. She claimed not to have realised that reports were routinely sent to MI5, but concedes it might have happened (most of the SDS reports that have been published for these hearings are marked as copied to MI5). She said she didn’t think much about this at the time.

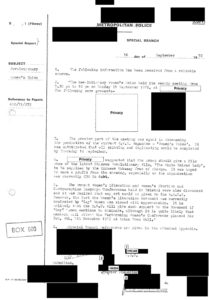

SHARING SECRETS

Sandra Davies’ report, 14 Sept 1972, stamped ‘Box 500’, meaning it was copied to MI5

The Inquiry was then shown a document [UCPI0000014736] which is Special Branch’s response to a request for intelligence from ‘Box 500’ – that is to say, the Security Service, MI5.

Two weeks earlier, they had asked Special Branch to find out about a couple of WRU/ LADWR activists’ recent house move.

It appears that Davies (whose name is attached to the report) was tasked to find out where they had gone, and duly supplied the information to her bosses, to send on to the security services. Davies said, again, that she had no memory of this.

She described some of the large women’s liberation meetings that she attended, some of which involved hundreds of women, and said that there were lots of stalls, leaflets being handed out, she didn’t have to work hard to be invited to meetings.

She checked in with her managers to get approval for any meeting she attended.

EXTREMISM & SUBVERSION

Officer HN45, ‘David Robertson’ was already deployed, and he gave her a presentation about the Maoist movement, and Abhimanyu Manchanda who led the Revolutionary Marxist-Leninist League.

Davies said:

‘I can’t remember one word of that presentation, but it was really a group that was opposed to our form of democracy’.

Asked what she was told about ‘subversion’ and ‘extremism’, she repeated:

‘We all understood that these groups were working against our form of democracy’

There was the feeling that she meant something else. Just as previous officers have conflated national security with the convenience of the government of the day, so Davies seemed to use ‘democracy’ to mean the current political hierarchy. As Dave Smith said yesterday, capitalism and democracy are not the same thing.

The SDS was spying on numerous open, democratic organisations, including political parties whose sole function was to participate in our form of democracy. Her close colleague Jill Mosdell was infiltrating the Anti-Apartheid Movement, whose sole objective was to bring democracy to South Africa.

Sandra said that her purpose was to see if the Women’s Liberation Front would ‘take direct action or whether it was just words’.

Asked if direct action was a problem, she said that in our country:

‘we’re entitled to our opinions and we can say what we like, well no, we can’t say exactly what we like but we’ve got Speakers Corner…. people can say what they like as long as they don’t go too far’

She seemed unaware that every regime on earth would describe their system in that way. Davies had a glaring absence of any questioning of the inherent rightness of the morals and intentions of the police and State.

DON’T DO CRIME

The next document was a Home Office circular about informants taking part in crime. Sandra does not recall seeing this before, but felt she understood the principles. She was very clear that she did not get involved in any criminal activities.

‘You’re there to uphold the law not break it… regardless of what role you’re playing’

According to her the police do use informants that are involved in criminality, but police officers shouldn’t get involved in criminality.

Were there rules about forming close relationships with activists?

Davies said she was told to ‘listen, learn and report back’, the spycops were not to get close to their targets. She was confident that officers in her day did not have sexual relationships with the people they spied on:

‘It didn’t need to be discussed specifically, it was something that didn’t happen’

Davies said she hadn’t heard about spycops deceiving people into relationships until she was contacted about this Inquiry, about three years ago. She hadn’t been to any SDS reunions over the years, so hadn’t heard stories from anyone else. She watched a documentary, ‘found it quite shocking’ and didn’t know what to believe.

MANAGEMENT

She described the SDS as being run by two Superintendents, a Chief Inspector, and two Sergeants.

Davies mainly reported to Phil Saunders and, to a lesser extent, HN294. They would have a direct debrief at the safe house.

She wasn’t provided with any back-up or support, she was sent out alone. She actually created her own security arrangements (with her husband) for travelling home late at night.

WOMEN’S LIBERATION

In her written statement, Davies said:

‘Women’s liberation was viewed as a worrying trend at the time.’

It seems clear that this is why she was recruited. Asked who exactly was worried by women’s liberation, she could only vaguely offer ‘all sorts of people’. She hurried to clarify that this didn’t mean those people were worried about the entire movement, just ‘factions within it’.

Counsel to the Inquiry then led her through a set of questions that exposed the hypocrisy and absurdity of Davies’ deployment in the Women’s Liberation Front.

She confirmed that, as a uniformed constable, she’d had the same powers and responsibilities as her male colleagues. However, women officers got 90% of the men’s wage at that time.

She was reminded of an violent confrontation in which she’d helped rescue injured officers and come back covered in blood. She was given no support or aftercare following the incident, beyond being told ‘you joined a man’s job so get on with it’.

According to her statement, the WLF mainly campaigned for equal pay, free contraception, and free nurseries. These are things that seem not just reasonable, but far more in keeping with a fair and just society than the practices of the police who employed her.

The policies and campaigning methods weren’t subversive by any real measure, so why was she sent to infiltrate the women’s movement, and specifically the Women’s Liberation Front?

Davies said it was because the WLF had links with ‘more extreme groups’. Asked if she was told the names of these groups that were supposed to be her true target, she once again became vague, referring to ‘a lot of unrest’ at the time. She mentioned the Angry Brigade, and added that the ‘Irish situation was very volatile’.

Davies’ own statement says the activists she spied on were not breaking any laws, just hosting meetings, leafleting and demonstrating – ‘all within the bounds of the law’ – and that she did not witness or participate in any public disorder during her entire deployment. So what was the point?

‘I was tasked to observe them because Special Branch did not know much about them’

IRISH CONNECTIONS

The Inquiry was shown a report [UCPI0000026992] of a WLF study group on 11 March 1971, comprising of seven people meeting in someone’s home.

Davies reported that one woman present praised the recent actions of the IRA, which she described as ‘a good way to start a revolution’. She’d put the words in quote marks.

We should note that, at this time, the IRA was only attacking British military targets in Northern Ireland. It is extraordinary that this comment on current affairs, made in a private home with no intent for action of any kind, was deemed worthy of reporting and filing by Britain’s political secret police. So much for ‘you are free to express your opinions’.

There seemed to be little else in the way of Davies reporting on the Irish situation she’d suggested as one of her true targets.

CHINESE CONNECTIONS

The next report [UCPI0000026996] was of another meeting of the study group, on 15 April, with 11 people present this time. Davies reported ‘general discussion’ of a ‘The East is Red’ – which she described as a ‘Chinese Revolutionary film’ – which was due to be shown twice that weekend.

Then came a report [UCPI0000026997] on a meeting of the Friends of China, that took place on 27 April. It was held in another private house, the home of Diane Langford, Besides Langford, her partner Abhimanyu Manchanda (a prominent Maoist), and Davies, there were only five other people present. Once again, Davies told the Inquiry that she had no memory of this meeting, but accepts that this report was hers.

According to the report, the Friends of China’s first matter of business was discussing the WLF’s magazine. Someone [their name is redacted] criticised the effort and resources put into it, before two members agreed to each take away 50 copies to sell.

There was more discussion of ‘The East Is Red’, which had been screened again, at the Cameo Poly Theatre in Regent Street. One person said it had shown too much violence, but another replied that there hadn’t been enough. A completely legal discussion about a legal film screened in a public venue.

The next document [UCPI0000027026] was a report of a WLF meeting, dated 8 December 1971. The speaker at the meeting had just returned from a trip to China and was ‘was clearly very impressed by the Chinese system’. This developed into a group discussion about all aspects of everyday life in China, including the use of acupuncture.

The speaker showed photos of life in China and is reported as saying Britain was ‘in desperate need of change,and that the Chinese methods would work here’; in his opinion ‘violent revolution’ was the means of achieving this change.

THE REVOLUTIONARY WOMEN’S UNION

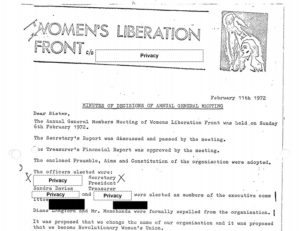

The Women’s Liberation Front held their AGM on 6 February 1972. They agreed to adopt a new constitution (that meant only women could be members) and new aims. There was also a proposal to change the organisation’s name to the Revolutionary Women’s League, but this was left for another meeting

Its new list of aims said it sought:

- ‘To organise women in general, working class women in particular, to fight for the elimination of all exploitation and oppression and for a socialist society.

- ‘To expose the oppression suffered by women and to relate this to capitalist society and to oppose those who confuse the effects of women’s oppression for the real cause, ie the private ownership of the means of production.’

This is entirely lawful, and not anti-democratic unless, like the spycops, you think democracy and capitalism are the same thing.

The group wanted to achieve these things as a path towards things that sound largely moderate and desirable to modern ears:

- ‘To demand equal opportunities in employment and education.

- ‘To fight for equal pay for work of equal value.

- ‘In order that women have real opportunities to take part in social production, we demand that crèches and nurseries are installed at the place of work, education and in the community, wherever there is a need.

- ‘All women should have the right to have children or not. In order to make this right effective, alongside child-care facilities, adequate contraceptive and abortion information and facilities should be made available free on the NHS.

- ‘To demand maternity leave for a definite period with no loss of pay, in the pre-natal and post-natal periods, and the right to return to the same job, guaranteed by law.

- ‘To fight against all discrimination and injustice suffered by women in all realms of society, in laws as regards marriage and divorce, in the superstructure; customs and culture.

- ‘To fight against the discrimination suffered by unmarried mothers and their children.

- ‘To wage a consistent struggle against male chauvinism and to strive to educate and encourage men to participate in all our activities.

- ‘To take our full part in the struggles against the growing attacks on our standard of living and our democratic rights and against the growing racism and fascist policies of the ruling class.

- ‘To mobilise women to support the anti-imperialist struggles of all oppressed peoples for the realisation of our common aim, the ending of the system of exploitation and oppression.’

ANGRY BRIGADE

Having cited the Angry Brigade as one of her true targets, she was asked about her reporting on them.

The Angry Brigade, a left wing group responsible for around 25 bombings in the early 1970s (the term should be qualified with the fact that they were relatively small devices and, between them, caused slight injury to one person).

Davies had reported [UCPI0000008274] attending a women’s liberation conference in 1972. She wrote that one woman associated with the Angry Brigade gave out copies of their ‘Conspiracy Notes’. The ‘Stoke Newington 8’ – a group of people facing serious charges connected with the Angry Brigade – were reaching out to other radical groups at the time for support.

The meeting was reported as chaotic, with calls for better structure to the discussion being heckled by Gay Liberation Front activists.

That appears to be the extent of her reporting on the Angry Brigade.

BLACK POWER CONNECTIONS

One of Davies’ reports [UCPI0000027028] was about a WLF weekly meeting that took place on 18 November 1971 – again in someone’s home – where 15 people attended.

There was a talk by Leila Hassan from the Black Unity and Freedom Party (BUFP)

There was a talk by Leila Hassan from the Black Unity and Freedom Party (BUFP)

Asked if Special Branch had asked her to pay special attention to this group, Davies said ‘not to my knowledge, no’.

Was she aware of the trial of the ‘Mangrove Nine’, a group being prosecuted following an incident in the Mangrove restaurant, a venue that had been raided by (racist) police officers many times?

Davies claimed to know absolutely nothing about this case, and nothing of Leila Hassan’s connection with them.

All in all, it seems Davies had done basically nothing about her supposed true target groups, only mentioning them in passing when they came into the orbit of the WLF.

SO WHAT DID SHE ACTUALLY DO?

The reports Davies made show a pattern of weekly WLF meetings held in the evenings at people’s private homes. They were mostly study groups, reading political texts and discussing them. One example [UCPI0000026990] describes reading ‘Lenin Conversation with Clara Zetkin’ which deals with women’s emancipation in 1920.

Asked how she avoided revealing anything personal about herself, Davies said it was easy because she was never asked. Others liked to talk a lot, and liked to be listened to. Yet she also said that she doesn’t remember those soliloquies mentioning any personal details about any of the people in the group.

She was asked if she ever felt uncomfortable spending time with those women every week, knowing that they didn’t knowing her true identity and role:

‘I was doing a job at the time, so I wasn’t – I don’t think I considered that, no. I was just doing my job.’

SUBVERSIVE BAKED GOODS

According to one of Davies’ reports [UCPI0000010932], the Black Unity and Freedom Party was planning a children’s Christmas party in 1971, and they asked the WLF to contribute home-made sweets and cakes.

Asked why the intention to bake was worthy of reporting by police charged with preventing disorder, Davies seemed to suggest it was a ruse to spring some indoctrination on the kids:

‘They were involving themselves with children and the sweets and cakes were an addition. They wanted to get their philosophy across to as many groups as they could. That was their aim’

Another of Davies’ reports [UCPI0000010907] mentions a jumble sale being organised by the WLF. Again, she defended this because:

‘they would have used it as another opportunity for advertising their aims’

Both of these reports were copied to MI5.

At this point, the fact that Davies herself admits the WLF’s aims didn’t warrant intrusion by undercover police is largely obscured by the absurdity of her claim that a jumble sale was a recruiting ground for radical political activist.

IDLE GOSSIP

Davies reported [UCPI0000010931] a letter which criticised an un-named activist for having an affair, and mentioned the termination of the employment of an un-named person (who may or may not be the same person – we can’t tell because of the name’s redacted) at Banner Books.

Why was it necessary to report this personal gossip?

Davies, yet again, didn’t remember, but accepted she had written the report.

Then how would it have helped effective policing of public order situations?

‘It just shows how the group was functioning… giving people an insight into what was happening at the time.’

She said that it wasn’t felt irrelevant by her managers, as it wouldn’t have got as far being typed-up if that were the case.

DIRECT INFLUENCE

Some of Davies’s reports are on meetings of the WLF Executive Committee. This was a group of six people, and the only way she could have been in those meetings is if she was a member. That required holding office in the group and thereby influencing its direction, something that SDS founder Conrad Dixon had specifically forbidden.

Women’s Liberation Front AGM minutes 1972, showing spycop ‘Sandra Davies’ elected as treasurer

The documents show that somebody called Sandra Davies was elected treasurer of the WLF (the same post that ‘Doug Edwards’ took in the Tower Hamlets branch of the Independent Labour Party).

Despite allegedly having no memory at all being on this Executive Committee, or attending any of these meetings, she was remarkably adamant that she didn’t influence the direction or policies of the group in any way.

The Inquiry returned to Davies’ report of the WLF Executive Committee meeting of February 1972 [UCPI0000010906] again.

This meeting appears to mark a change of leadership and a change of direction for the group.

This was when the idea of changing the group’s name to the Revolutionary Women’s Union (RWU) was first formally proposed, and eventually agreed. As part of such a tiny group, how much influence did Davies have? Was she responsible for its adopting a more radical, ‘Revolutionary’ name?

A month later, Davies reported [UCPI0000010911] on an emergency meeting of the RWU’s Executive Committee.

This time, the Committee decided to suspend three members from the wider group for ‘disruptive behaviour’. They agreed to serve them the three with written notices of suspension, and spend three weeks compiling a dossier with details of their ‘disruptive tactics’. These would then be circulated to all members.

Despite this prolonged, controversial and divisive work being agreed and carried out by the small group, Davies says she remembers none of it.

Did she remember that this internal division then led to reduced enthusiasm and drive within the group?

‘I can’t comment on that. I have no idea’.

Six weeks later, on 4 May 1972, Davies attended another Women’s Revolutionary Union meeting at a member’s home.

According to her report [UCPI0000010913], it opened with comments about a general lack of enthusiasm within the group, older members dropping out and not being replaced by new ones. This appears to be a direct consequence of the suspensions Davies had a hand in. One of those present was convinced that her phone was tapped, and warned/ reminded the others not to discuss their WRU activities over the phone.

END OF DEPLOYMENT

Davies’ deployment was terminated in February 1973. There had been ‘an incident’ involving another officer, HN45, ‘David Robertson, with a risk of his cover being blown. As a result, he, Jill Mosdell and Davies were all withdrawn from the field at the same time.

Despite serving in the Met’s elite subversion, demonstration and disorder unit for two years, Davies said in her witness statement:

‘I did not witness or participate in any public disorder whilst serving with the SDS. I do not even recall going on any marches or demonstrations. I did not witness nor was I involved in any violence.’

Looking back, she continued:

‘I do not think my work really yielded any good intelligence, but I eliminated the Women’s Liberation Front from public order concerns’

That is a mitigation that could be applied to thought-crime spying on literally anyone. More to the point, it was a fact that must have been obvious very early on in her deployment. And yet, she was still there, spying full-time on that group, two years later.

There was no suggestion that her managers gave much thought to whether what she was doing was worthwhile. As with other deployments, it seems that once they had their spycops in place, keeping them there was more important to the police than the information they gathered.

The rights of the people being spied on – who had police officers in their lives and homes week after week – didn’t get a look-in.

Had it not been for the incident with HN45, she probably would have stayed on even longer, as there was ‘no indication’ that her managers wanted to withdraw her. Nor is there any indication she would have left:

‘I was submitting my reports and was guided by superior officers’

Davies told the Inquiry that she stood by what she wrote in her statement:

‘In hindsight, I would not have joined the SDS as I was putting myself too much at risk and there were more worthwhile things I could have been doing… I question whether police officers should be undercover at all’

And that remains her view now, 50 years after being deployed herself.

Here ended the Counsel to the Inquiry’s questioning.

ARE YOU SURE ABOUT THAT?

After this, Ruth Brander, representing non-state core participants at the Inquiry (ie people who were spied on), was permitted to revisit three of the topics raised.

First, Brander asked about the SDS officers meeting at the safe house. Davies had said they much of the day was spent waiting around, yet did not discuss much detail of the deployments that they were all immersed in. What did they talk about?

Davies said the spycops would write their draft reports, and wait for their turn to have one-to-one talks with the managers. She said the atmosphere was good and – despite the common values of the times and them being outnumbered by men – the women officers were not subjected to any sexist behaviour.

So, Brander asked, if they didn’t talk about the people they spied on, what were the topics of conversation?

Davies said it was general chat, probably ‘holidays and houses and families’.

Moving on, Brander asked if, although she said she wasn’t aware of any sexual relationships between spycops and people they targeted, there were other emotional involvements, such as going out for dinner or drinks. Davies insisted not.

SPYING ON CHILDREN

Finally, Brander asked about Davies’s report [UCPI0000010928] on a school strike organised by the Schools Action Union in May 1972.

Several North London schools had taken part in the strike with a list of demands that, rather like the Women’s Liberation Front’s calls for an end to gender inequality, appear moderate:

- Teacher-pupil committees to run the schools

- No school uniforms

- No corporal punishment

- Free school meals and milk

- Freedom to leave school during the lunch break

Davies said that she hadn’t been involved in it, she would just have picked up details from what people said.

Brander asked if she’d given any consideration to the appropriateness of reporting on school children.

‘I wasn’t reporting on children,’ Davies protested.

‘Well, the report here is about action taken by children, isn’t it?’ Brander pressed her.

Davies, her memory apparently intact now, replied:

‘I don’t know anything about the Schools Action Union, I wasn’t involved in any of that.’

Brander’s eyebrow could be heard raising, even through the silent transcription. She pointed out that it’s quite a lengthy report – running to 13 separate numbered paragraphs of intelligence – with a lot of detail. It named several of the children who’d been arrested.

The fact that the typed report exists means that, as with the others, it was discussed and approved by the spycops’ managers.

The accompanying written witness statement from HN348.

COPS will be live-tweeting all the Inquiry hearings, and producing daily reports like this one for the blog. They will be indexed on our UCPI Public Inquiry page.