UCPI Daily Report, 16 Nov 2020

Tranche 1, Phase 1, Day 11

16 November 2020

Evidence from:

Officer HN336 aka ‘Dick Epps’

Officer HN340 aka ‘Andy Bailey’ or ‘Alan Nixon’

At the Undercover Policing Inquiry, Monday 16 November was taken up by hearing evidence from two former spycops. Both were deployed between 1969 and 1972. Both have scant memories of key incidents, yet still yielded vital details.

Last week we learned that many of the spycops abuses of power ‘- deceiving people they spied on into relationships, attending family events, spying beyond their jurisdiction – were around from the very earliest days of their unit. Today we added another one to the list – another MP has been confirmed as being spied on by these officers of the counter-democratic political secret police.

SELECTIVE AMNESIA

Tom Fowler, who was spied on in the 2000s by officer ‘Marco Jacobs‘, has been following the hearings and said:

‘Given that the events being talked about are up to 52 years ago, it doesn’t seem unreasonable that memories of the details of many events don’t come to mind.

‘However, it is very telling that all five of the former professional falsifiers had rather good memories on certain matters, generally ones that absolved them of blame, like “it was definitely just one drink one, one time”, only to have blank memories on other issues that might unearth more detail on what kind of operation Conrad Dixon was running with the Special Demonstration Squad, like “my closest colleague acting as a prosecution witness in a case that successfully convicted an innocent man of incitement to riot, based on a leaflet she collected at a meeting I attend with her? I really can’t remember anything”.

‘No one remembers any discussion with any of the colleagues about anything to do with any of their deployments, even ones that overlapped their own undercover roles…

‘A number of the officers remarked that the evidence bundle that had been presented to them was missing an unknown number of reports they had written… [while there are] plenty of others which bear the names of officers who dismiss the contents as “far too eloquent” for anything they might have written.

‘You begin to get the impression that one section of the SDS was putting together all the reports that justified the existence of the unit, whilst the rest of the officers were there to sign off whatever was written, regardless of whether they had picked up the intelligence themselves or not.’

GUERILLA COVERAGE

The Undercover Policing Inquiry still refuses to live-steam its hearings, only giving us a time-delayed on-screen transcript that can’t be paused or rewound. It makes the whole process much harder to follow.

The women from Police Spies Out of Lives, which represents women who were deceived into relationships by spycops, have taken matters into their own hands by doing a live feed of them reading the Inquiry’s transcript.

There is, of course, no reason why the Inquiry can’t provide us with its audio of the hearings. It would be no different to the readalong in terms of security. It’s further evidence of the way regards victims of spycops as marginal and the wider public as an irrelevance.

Once again, it falls to those abused by spycops to do the work to bring the facts to the public. This one doesn’t even have security excuses, it’s just that they feel the public are an irrelevance.

Follow the readalong when the hearings are happening on the Police Spies Out of Lives YouTube channel.

Back to the day at the Inquiry:

‘Dick Epps’

SDS officer HN336

‘Day 11’ of the Undercover Policing Inquiry began with the testimony of officer HN336 – ‘Dick Epps’.

In his time undercover in the Special Demonstration Squad between 1969 and 1972, Epps infiltrated:

- Britain Vietnam Solidarity Front

- Vietnam Solidarity Campaign

- British Campaign for Peace in Vietnam

- Stop The Seventy Tour

- International Marxist Group

Later, he worked for Special Branch’s Industrial Section and appeared as ‘Dan’ in the 2002 BBC documentary True Spies.

Dick Epps’ testimony touched on several issues, including chauvinistic reporting of targets, Special Branch burglaries, and the connection between Special Branch and the blacklisting of trade unionists.

Counsel to the Inquiry, David Barr, kicked off proceedings by asking the former undercover questions around search warrants – your general police training, pre-Special Branch – did it cover entering private dwellings?

Epps answered that it did so. However, there was no special training regarding attending political meetings – Special Branch officers learned ‘on the job’. This included how to write up reports – he was expected to record who attended meetings (if he could identify them) and admitted that just attending a meeting was enough for someone to be included in a report.

He was given verbal instructions, and provided with general support by his colleagues:

‘I was never sat down in a classroom or a training room and given a training manual, or training lectures… We were all, if you like, being thrown into a maelstrom, and seeking to find some sense of what we were trying to do’

He admitted that there was no actual training or briefing about the groups that were being spied on.

Epps couldn’t recall making a separate report about any person but did talk about how someone might draw attention to themselves at a meeting and this would be recorded.

Epps also described it as a ‘fundamental requirement’ that undercovers report on a group’s plans, activities, discussions and interests. He then spoke about those days being different and added that ‘political correctness’ hadn’t been invented yet. He said that his superiors were always curious about the content of his reports, but didn’t give him much feedback. Reports would be altered and ‘tweaked’ by the SDS office staff to match the ‘style’ used by the unit.

Later he added that his reports would include personal details of any ‘new faces’ he met at these meetings – though he claimed he had no idea if this info was used for vetting or not. However, he had admitted to working within Special Branch for five years before joining the SDS, and knew that most forms went to MI5.

SUBVERSION

As with previous witnesses, he was then asked about his understanding of the term ‘subversion’. Specifically, what he meant by distinguishing (in his written statement) between ‘peaceful genuine protest’ and that which was ‘divisive or venomous’ – was that a personal distinction or an official one?

His answer eventually settled on it being more a personal one:

‘my feeling was, and is, that we existed within a very sophisticated political system that’s evolved over many years, and there is an order to the way that system might be changed. As a parliamentary democracy, it’s through the ballot box.

‘And there were and are those that seek to disturb that balance of matters and subvert that system by other means. And so that would be, in the broadest terms, my understanding of “subversion”.

He was asked how secretive the SDS was within Special Branch – he thought that in the early days some people within the Branch knew of the new unit’s existence, but many did not: ‘you didn’t ask questions’.

Oddly, he has also claimed that he was never actually ‘targeted’ into any specific group or individual, but just went out ‘fishing’ to see what groups he could latch onto. In fact, something that stood out strongly with Epps (as well as some of the other undercovers) is that he seemed to drift aimlessly between one group and another.

BRITAIN VIETNAM SOLIDARITY FRONT

The first group that Epps spied on was the Britain Vietnam Solidarity Front (BVSF) – politically Maoist in belief. They met weekly at the Union Tavern Pub on King Cross Road and the meetings were large enough (20-25 people) that a new person wouldn’t stand out too much.

Epps protested that for the BVSF:

‘I think “infiltration” sounds rather too strong a word. I attended the meetings and I was interested from a professional point of view in terms of learning what their viewpoints were, and also trying to glean anything from that that might take me elsewhere, in time.’

He also said the BVSF provided him with a useful introduction to political nuances and the various factions that existed at the time. He hoped it would be a ‘gateway’ to other groups.

The Union Tavern, Kings Cross Road. London

He said he was never an established member of the group, even if he became ‘an accepted part of the furniture on a Sunday evening’. He saw his task as keeping tabs on people who were seeking to disrupt the status quo.

He was asked about Tariq Ali and Abhimanyu Manchanda, who he described as ‘prominent individuals’. He wasn’t given any briefing about either man by his managers but would report back on them.

Epps later commented on both individuals of being worthy of SDS attention, claiming that their rhetoric, especially that of Ali, could stir-up trouble. However, when pressed, he could not give examples of violence from either group.

Barr then asked him about a deceased member of the SDS, Mike Ferguson, inquiring as to why both officers had infiltrated the BVSF at the same time – and how it came to be there were reports signed in both their names.

Epps explained that he was ‘a new boy’ and this was an opportunity for him to ‘learn a trade, learn a skill that I was going to find useful’. However, he denied collusion with Ferguson: ‘We would not sit down together and compile a report, no’.

He suggested that SDS officers had an advantage over normal Special Branch officers:

‘the fact that your face was known made it possible to sort of glide in and slide into the grouping, rather than stand out as a total stranger. There was always a sensitivity about strange faces.

He tried to stress that the context of the time as a justification for the surveillance:

‘it was a hotbed at that time of — of street activity. And some of it was — was very reasonable in its protest, but some of it was really, really violent… And so there was a need to protect, if you like, as I say, in the wider sense’

Then another nickname for the SDS officers unit emerged – he called them ‘the Hs’, short for ‘Hairies’.

One of his reports from a BVSF meeting included details of two forthcoming marches, one about Palestine and another about women’s equality. Epps was at pains to tell us that his focus was the group, not these issues, even though he reported on them.

Barr asked him bluntly, ‘From what you could see of the BVSF and its members, was it a violent organisation?’

Epps had to concede:

‘No, not compared with other groupings at that time, no.’

CAMDEN VIETNAM SOLIDARITY CAMPAIGN

After some time with the BVSF, Epps moved on, to the Camden branch of the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign (VSC). Asked why he left the BVSF, he explained that it ‘got to a point where I felt uneasy…there was never finger-pointing, or a moment where any accusations were made’ but he felt that its leader Manchanda was suspicious of him, and read it as the time to move on.

Epps noted that Camden VSC had previously been infiltrated by SDS founder Conrad Dixon. The officer recalled that the group had remembered Dixon as a ‘figure of fun’ recalled by the Camden VSC members as wearing ‘a yachtsman’s outfit’ – he had a ‘big sailor type beard’, a ‘jaunty’ cap and a smock – ‘slightly out of place in Camden, dare I say’.

He described the Camden VSC group as ‘loose-knit and very friendly’, with ‘wide-ranging views’. He developed the impression they ‘had a Communist party leaning’ and they referred to him as a ‘Trot’, and therefore a reformist in their eyes.

Justifying it, Epps said:

‘The whole objective of the penetration of what was going on was to provide your individual persona with credibility.’

He subsequently moved on to target the Kentish Town VSC, but had very few memories of that branch.

BRITISH CAMPAIGN FOR PEACE IN VIETNAM

Next, Epps targeted a north London branch of the British Campaign for Peace in Vietnam (BCPV). This entailed attending meetings that were held in a private house, though he did not recall any reaction from his managers to this.

His witness statement mentioned regularly going out for post-meeting drinks with members of this group throughout the six months that he was infiltrating them.

One of the members was a woman with whom he later went out for a drink. He made sure to state:

‘There was never anything beyond that ordinary conversation. If she had any desire to develop a relationship or a friendship, she didn’t convey that and neither did I.’

He said they just had a ‘nodding acquaintance’ relationship afterwards. He believes going out for drinks with her aided his acceptance and credibility in the group. This obviously foreshadows the use of women to gain access to activist groups.

Later in the hearing, after Barr had finished questioning Epps, barrister Ruth Brander, on behalf of non-state core participants, was also permitted to ask him a couple of questions about this drink with the woman from the BCPV. He confirmed that he could even still recall her name, fifty years later, but brushed away the idea there was any significant reason for this.

STOP THE SEVENTY TOUR (STST)

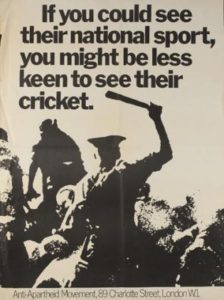

Epps next targeted the anti-apartheid Stop The Seventy Tour having been introduced to this campaign by a member of the BCPV. (Peter Hain, a member of this group and due to give evidence in the Inquiry next year, recently made an impassioned speech in the House of Lords against the current CHIS Bill, most of which is in a Guardian Column today.)

Peter Hain, arrested at Downing Street, 1969

STST opposed sporting tours of white South African teams in the UK, and British teams going to play in apartheid South Africa. Epps recalled ‘there was a lot of passionate revulsion’ towards the apartheid regime.

His witness statement mentioned two incidents – digging up the pitch at Lords cricket ground and pouring oil over the wickets – but Barr explained that the Inquiry has been unable to find any press coverage of such an event during the STST’s campaign. This issue was later pursued in questions by the Chair himself, and at that point, Epps conceded he had muddled up events.

Epps did talk more about the STST activists, citing an incident at a match he attended with them. STST tried to disrupt these matches, with the aim of delaying play, or better still, causing the entire match to be postponed. The group’s tactic was to ‘rush’ the pitch, upon a given signal. Epps could not recall what this signal was, or who gave it, but says the activists tried to ‘push the police around’, and alleges that one or two of them even threw punches at uniformed officers, something he found hard to watch.

Barr then returned to the undercover officer Mike Ferguson, reminding Epps that he had described Mike as ‘Peter Hain’s right-hand man’ in his statement. Epps now claimed he had meant that as a bit of a joke. He added that you did not have to go as far as Ferguson to do the job – but admitted that he lacked the ‘drive or nouse’ to be as effective as some of the other undercovers.

ANARCHY IN THE UK

On more than one occasion in his written evidence, Epps claimed it was anarchists who were the likely cause of any public disorder. Reasonably, Barr asked why in that case he did not attempt to infiltrate the anarchist groups?

Epps responded with some reminiscing about some ‘spontaneous moments by hair-brained bunches’ including ‘a dozen or so cars set alight in the vicinity of Claridge’s’ when Ronald Reagan visited London in the 1980s.

When pressed Epps said:

‘I don’t know that it ever occurred to me that that was a route that I might find useful. But some of them were, as I say, harebrained and a little overexcited at these moments, and I didn’t feel drawn to that sort of grouping.’

Putting aside the accuracy of Epps opinions about anarchism, this seems wholly at odds with the SDS’ supposed public order remit.

RACIST & SEXIST REPORTING

Again, in regards to his infiltration in the London STST committee, Epps wrote a report about a member of the group:

‘She is, in fact, a somewhat immature, naïve person and it would seem that she was made Secretary of the group because of her clerical experience.’

More worryingly, he went on to describe her physically:

‘Aged about 23 years; height 5’0″; short fair hair; slim build with well-developed bust; slightly Jewish appearance’

Barr asked him to explain this racialised and sexualised reporting, and suggested that the reports were based on stereotypes.

‘Can I say, that’s a modern-day interpretation and not how it would have been viewed then?’

In a similar manner, Epps also described another woman as being ‘attractive’. He was unable to explain how useful either of these descriptions would have been to Special Branch.

Epps was asked more about the STST campaign’s plans. This included a suggestion that they hold a torch-lit midnight procession. Why did the police need to know about an entirely peaceful demo? According to Epps, street demos are ‘still something that the police should be aware of’.

The officer also said he didn’t get to know members of the STST very well, but rather he ‘drifted in and out’.

INTERNATIONAL MARXIST GROUP – BURGLARY

Epps said he does not remember how he first got involved with the International Marxist Group (IMG). They were possibly targeted because they ‘took part in every demonstration going’.

He admitted that he didn’t remember any IMG members being violent or disorderly at demos but claims ‘they were much busier than other groups’ – as if that was justification in itself.

He admitted that he didn’t remember any IMG members being violent or disorderly at demos but claims ‘they were much busier than other groups’ – as if that was justification in itself.

Epps said he was instructed by his managers to make a copy of the IMG’s office keys. He had also mentioned this in True Spies, where he claimed he ‘just happened’ to have clay on him to take the pressing. Today, however, he admitted he had told his boss he had an opportunity to get a pressing of the key and was then told to go ahead, possibly with plasticine provided by them (his oral and written evidence vary on this).

Under questioning, Epps gave more details. He recalled attending an IMG meeting, where they were looking for someone to look after the office. He ‘reluctantly volunteered’ for the task. Epps also intimated that burgling activists offices was not something that Special Branch would do – although there are countless anecdotal reports, spanning many years, of mysterious break-ins of campaign premises where nothing was actually taken.

FALL OUT FROM ‘TRUE SPIES’

Epps said that he lost a lot of good friends as a result of taking part in the BBC TV series True Spies, even though his participation was authorised by Special Branch.

He was ‘still at a loss to understand’ why they were so upset and was disappointed ‘that some seemed to take such exception to rather frivolous comments.’

Barr then asked: Do you think your colleagues were upset because they were concerned you had compromised the operational security of the SDS, or did they regard you as a whistle-blower?

Epps replied:

‘I don’t think they viewed me as a whistleblower. I think it was just a rather shortsighted thing to have said on my part. And maybe they were right in that respect.’

As with all police witnesses to date, he loyally gave his colleagues an absurdly uncritical tribute as a ‘committed bunch of individuals and people I have great admiration for. ‘

However, earlier in the questioning, Epps made some seemingly less than favourable comments about SDS founder, Conrad Dixon – in contrast to previous police witnesses – saying that he was a dominating force in a manner that wasn’t wholly positive.

His written witness statement said:

‘Conrad was a clever man, but also an ambitious and devious man. He saw an opportunity for himself as well as an opportunity to create something useful.

Barr asked Epps to elaborate on this, and he replied:

‘personally, to me, would always come across as a gambler. And I don’t mean that in a well, a chancer. He was brash.’

SPECIAL BRANCH INDUSTRIAL SECTION – AND BLACKLISTING

At the beginning of this part of the questioning, it was revealed that Chief Superintendent Bert Lawrenson, the former head of C Squad in Special Branch, who spied on left-wing union activists, went on to work for blacklisting and union-busting organisation The Economic League after the left the police.

Epps later worked in the ‘industrial section’ of Special Branch. He covered the engineering sector and described the concerns regarding Soviet infiltration of that industry. However, to his knowledge, SDS officers had nothing to do with the Economic League although they ‘swam in the same pond’.

Recalling an induction lecture at Special Branch, ‘I remember being quite alarmed by Lawrenson’s assessment of the infiltration of British groups by the Russians’. Epps claimed that ‘people would come to us’ – suggesting these were trade unionists who were ‘not tainted by communism’. This information was included in True Spies as well.

Barr pressed Epps to confirm that, while at the industrial desk, Epps would have access to Special Branch records – given that if the SDS had reported someone’s trade union activities, that report would have been available to the Industrial Section of Special Branch?

Epps replied, claiming:

‘There would be no overlap between the – whatever was held within the SDS would remain there. I can’t conceive of any situation where SDS information, intelligence would leak into the normal pool of Special Branch records activity.’

This would seem strange, as some, if not all, SDS reports were fed into the enormous Special Branch registry file system. However, he did agree that it was ‘reasonable to assume’ that many of his reports went to MI5.

After Ruth Brander asked her questions about Epps’ drink with a member of the STST committee, Owen Greenall, a barrister appearing on behalf some non-state core participants, asked about the dates of his deployment and the STST’s actions at Twickenham. However, Epps said he didn’t make any written record of these events. There ended a lengthy first session.

PDF of the accompanying written witness statement of HN336 ‘Dick Epps’

‘Andy Bailey’ or ‘Alan Nixon’

SDS officer HN340

In the afternoon, we heard evidence from officer HN340, who infiltrated various groups – including the International Marxist Group (IMG), North London Red Circle and Irish Solidarity Campaign – between 1969 and 1972.

He is now known to have used the cover names ‘Alan Bailey’ and ‘Alan Nixon’. Here’s his Undercover Research Group profile.

Though it’s not his real name, we’ll call him Bailey in this report for ease of reading.

BEFORE THE SPYCOP

Bailey joined the police in the 1950s. He can’t remember much about the first two years of probationary training, or being told anything much about ethics or standards.

He then joined Special Branch in the 1960s. There was a written exam. He said that he was not required to do any undercover work prior to joining the spycop unit.

Occasionally Special Branch officers would go along to Speakers Corner, in their normal clothes, but he never went to any ‘closed meetings’.

JOINING THE SPYCOPS

After about five years in Special Branch, Bailey was invited to join the Special Demonstration Squad by Phil Saunders. He was only then given an outline of what the unit did, and was told it would involve weekend working.

The unit wasn’t well-known. He said he knew ‘basically, nothing’ about the SDS before joining it. This was, he explained, in keeping with the wider Special Branch ethos of working on a ‘need to know’ basis; ‘you didn’t need to spell it out’.

His written witness statement recounts a conversation with Mike Ferguson, who had already been deployed undercover by the SDS. Ferguson advised Bailey to get a cover name, cover address and cover job.

In today’s hearing, Bailey couldn’t clarify where this conversation had taken place – at first he claimed it had been in the ‘back-office’ at Scotland Yard, but then he admitted that Ferguson would never have visited the building while deployed undercover.

STOP THE SEVENTY TOUR

He claims not to have known much about Mike Ferguson’s role in the Stop the Seventy Tour (STST) campaign, or his position in the anti-apartheid movement – something the Inquiry seems to be asking every officer about.

The Inquiry seems to be focusing on a few ideas that now fit with modern mainstream sensibilities – that apartheid was wrong, or that singling out people for their disabilities is unacceptable – rather than seeing them as part of the SDS’s wider attack on progressive politics and citizens’ personal integrity.

The Inquiry seems to be focusing on a few ideas that now fit with modern mainstream sensibilities – that apartheid was wrong, or that singling out people for their disabilities is unacceptable – rather than seeing them as part of the SDS’s wider attack on progressive politics and citizens’ personal integrity.

Bailey didn’t create any kind of back-story or ‘legend’ for himself, and in retrospect admitted that this might have been useful later on.

Like all SDS officers, he spent a little time in the ‘back office’ of the unit, ‘probably typing up reports and checking out various bits and pieces’, which will have given him an idea of what would be expected from him when he went undercover.

He doesn’t recall other former or waiting-to-be-deployed undercovers being in the back office at the same time as him (somewhat contradicting his earlier written statement, according to Rebekah Hummerstone, who was asking questions for the Inquiry).

Bailey didn’t recall much preparation, and confirmed that he received no training in undercover work. He said Ferguson told him to ‘play it by ear’:

‘I was hoping he might have given some pearls of wisdom but as I said once you’re out there nobody knows exactly what’s going to turn up next and you’ve got to be prepared for anything’

Bailey’s written statement said that as an undercover you ‘were trusted to use your common sense and good judgement’.

He does not recall receiving any guidance about entering private addresses, even though he did inevitably attend meetings held at activists’ homes.

He would go the SDS flat each day and write up his report of the previous evening’s political meeting. His reports would routinely include details of the group’s plans and events, and personal information, including identifying information, about the individual people he met. They would then be typed up by back-office staff.

Bailey’s memory has a lot of gaps which, after 50 years, isn’t really surprising. Did he see any of his reports after they’d been typed up? Did he see them to sign them? He doesn’t recall.

He expressed surprise that any of his reports are still in existence 50 years later, and is sure the ones he’s seen are only a fraction of the ones he made:

‘there are certain little incidents that I do have vague recollection of, which aren’t contained in the bundle’

Pressed for details on what this meant, after he consulted with another person, he said he remembered the explosion at the Post Office tower, for example.

On 31 October 1971, a bomb went off in the restaurant at the top of the Post Office Tower (now BT tower) in central London. Responsibility was claimed by the IRA, and later by the Angry Brigade anarchist collective.

Bailey had attended a ‘function’ with members of the Irish Solidarity Campaign nearby that evening. Senior officers, who must clearly have been aware of which groups he was infiltrating, asked him if he had any information that might help their enquiries. However he had left the area when the pubs closed and ‘it must have occurred after that’ (the explosion came at 4:30am).

Bailey stated his role was to gather intelligence about forthcoming events, pickets and demonstrations, in order to prevent public order problems. His statement says that Special Branch had no formal role in counter-subversion.

However, he said the SDS (and therefore Special Branch) did collect information about people who were ‘unfriendly towards the State and its institutions and might use criminal methods to undermine it’. In fact he went on to say that this ‘secondary role’ was in fact one of Special Branch’s ‘main functions’.

However, he said the SDS (and therefore Special Branch) did collect information about people who were ‘unfriendly towards the State and its institutions and might use criminal methods to undermine it’. In fact he went on to say that this ‘secondary role’ was in fact one of Special Branch’s ‘main functions’.

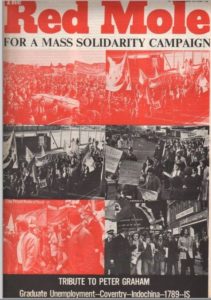

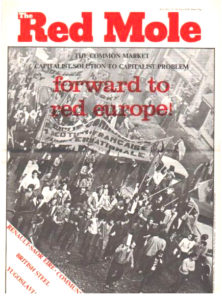

RED MOLE

The spycops worked weekends; Bailey often stood outside Archway tube station selling Red Mole, a newspaper edited by Tariq Ali that was the voice for many in the International Marxist Group.

Bailey estimated that he only went to his cover accommodation two or three times a week, and only slept there ‘very rarely’.

In contrast, he visited the SDS flat almost every weekday afternoon, as did most of the other spycops at that time, where they would write up their reports. He described this a functional arrangement, and spycops didn’t really discuss their experiences with each other, not even in a ‘sanitised’ way.

His written witness statement suggested that his deployment was very open-ended – and he could be ‘re-tasked’ as necessary.

Bailey said a lack of praise was a continual feature of his work, and that he just made up his methods and activities, and presumed he was doing the right thing unless his managers told him otherwise:

‘If they’d thought it was a waste of time I’m pretty sure they would have said “don’t bother”.’

Managers regularly visited the SDS flat but Bailey doesn’t remember being given many specific instructions by them, or directed to infiltrate any specific groups.

Rebekah Hummerstone, the Inquiry’s barrister carrying out the questioning, said that we know they did step in to give some direction on at least two occasions, telling him – and told him not to become a member of the International Marxist Group, and that he should to attend the Conference for a Red Europe in Brussels in November 1970, organised by the Fourth International (of which the IMG was a part)

He accepts that his attendance of a meeting at Conway Hall must have been on instructions:

‘I must have been told because I wouldn’t have gone off wandering off to Red Lion Square just off my own initiative’

There was a lot of this in his answers – an inability to recall events at all, let alone in detail, but a readiness to accept the accounts and implications of the documents. This contrasts with other officers’ evidence that the reports were often written by their superiors, without their knowledge, or that reports were credited to the person did the typing rather than the one did the spying.

The report of the Conway Hall meeting says Bailey approached and talked with both Tariq Ali and Vanessa Redgrave. They had both spoken at the meeting, he didn’t know anyone else, so did what Ferguson had recommended, he ‘played it by ear’, and went over for a chat. Ali invited him to attend the next meeting of the North London Red Circle.

Bailey didn’t think he had heard of the Red Circle before, he’s not sure if his managers were very aware of the group, they certainly hadn’t tasked him to target it; he fell into it by chance because of this encounter with Ali. He hoped that attending Red Circle meetings would provide him with useful intelligence about ‘potential flash points’.

NORTH LONDON RED CIRCLE

Bailey’s written witness statement described North London Red Circle as a ‘recruiting ground for the International Marxist Group’, with a presumption that the IMG was in itself a serious threat to public safety, so anyone in its orbit was fair game for spying.

Bailey became the Red Circle’s ‘tea club secretary’, on his own initiative, in order to learn the names of group members. Echoing what other spycops have recounted, he said he felt it was best to gather as much information as possible, in case it became useful later.

The reports show the Red Circle was a tiny left-wing discussion group. It held talks on Israel, Black Power, trade unions, the Fourth International, the National Union of Mineworkers, the Upper Clyde Shipbuilders’ dispute, anti-racist campaigning, unemployment, apartheid, and more.

Asked about the content of these meetings, Bailey once again only offered an apologetic blank memory.

SPYING ON WOMEN’S LIBERATION

Another report was about a meeting on the topic of women’s liberation. The speaker talked about attempts to form a union for women night cleaners.

When queried on the relevance of these campaigns and whether Special Branch spied on the trade union and women’s liberation movements, Bailey said he didn’t think he could speak for Special Branch as a whole, and then failed to speak even for the Branch unit he was in.

He agreed that this report was a good example of him writing down everything that might possibly be of interest, and leaving it to the back-office to decide what to include in the final typed-up version.

IRISH POLITICS

An August 1971 report on a Red Circle meeting [UCPI0000008196] describes an unusually large crowd for the group – all of 24 people – were present to hear a talk by a Provisional sympathiser followed by questions.

The speaker said that if the IRA did commence terrorist activities in England, they considered it the ‘duty of all revolutionaries to render whatever assistance was asked’. Bailey can’t remember if any Red Circle attendees agreed with this view.

Thirty people attended a Red Circle meeting in February 1972, according to Bailey’s report [UCPI0000008944], to hear civil rights campaigner Bob Purdie speak about Ireland, in place of a scheduled talk about Spain.

Purdie talked about the Republican movement, explaining that the recent split was due to tactical differences rather than political ones. In answer to a question afterwards, Purdie said extending the armed struggle to England would be politically wrong, but if the Irish movement’s leaders called for assistance, then the IMG line was that revolutionary groups in Britain should support them.

Bailey admitted that the name Bob Purdie rings a bell, but he could not remember much more. Again, he followed his absence of specifics with supposition because on residual understanding of the group:

‘From what I remember I can’t think of any of them now that I would consider to be tending towards any kind of violence”.’

A very faint report from April 1972 shows the Red Circle again having a talk about Ireland because the scheduled speaker (this time on Cuba) couldn’t make the meeting on the day.

The Red Circle ‘was a talking shop’, Bailey said in his written statement to the Inquiry:

‘It did support a revolutionary agenda and was subversive to the extent that it advanced the overthrow of the established political system in the UK, albeit never took any concrete steps… violence would have been the last thing on many of their minds’.

IRISH CIVIL RIGHTS SOLIDARITY CAMPAIGN

Bailey also infiltrated the Irish Civil Rights Solidarity Campaign (ICRSC). His name appears on a report on the group’s activities filed in September 1970.

He said he attended their meetings ‘almost as a co-opted member of the North London Red Circle’ but struggled to explain why.

Bailey doesn’t remember being ‘tasked’ to attend the ICRSC meetings, it was again more a case of chance, but that it his managers had disapproved he would not have gone.

IRISH SOLIDARITY CAMPAIGN

His involvement with the ICRSC resulted in Bailey attending the founding conference of the Irish Solidarity Campaign (ISC) in Birmingham, in October 1970.

It was unusual for an SDS officer to go beyond London. Asked if he got special permission to make the journey to another constabulary’s jurisdiction, he once more failed to remember anything:

‘I must have slept somewhere overnight… but quite honestly I can’t remember where we stayed’

For an SDS officer to go beyond the Met’s area, the unit must have either secured the permission of the local police, in which case they were complicit in what the spycops did, or else it was done without local approval, which is a serious breach of police protocol.

That Irish Solidarity Campaign founding conference was also attended by Bailey’s colleague, SDS officer HN68 ‘Sean Lynch’, whose deployment was mainly focused on Irish solidarity groups. The two tried to avoid any contact – ‘there was no reason that we should know each other, so we didn’t’ – but Bailey thinks it likely they knew of each other’s plans to attend the event in advance.

A report was produced afterwards, with both their names attached to it. Bailey has no recollection of collaborating on this with HN68, but ‘it seems as if it would have been inconceivable that we hadn’t discussed it’. The report contained a long list of all the groups (and ‘fraternal delegates’) who attended the conference.

He explained:

‘They were there and so I reported it; it was then down to the back office to do their filtering, vetting, or whatever you call it.’

The report was sent not just to MI5 but also to the Home Office. The Deputy Assistant Commissioner commended the ‘first class work’ and asked that the officers be praised (though Bailey does not remember receiving or being told about such praise). It will have been obvious to that senior officer that the depth of knowledge in the report can only have come from sustained infiltration.

There is no way to sustain the claim we’ve heard from the Met that the SDS was a rogue unit, so secret that nobody outside really knew what was going on.

It is already clear – and getting even clearer – that the SDS’ work was known and approved of at the highest levels of the Met, as well as its paymasters in the Home Office who have managed to lose every single document about their 21 years of direct funding.

Hummerstone read out the six main aims of the ISC (as laid out in Appendix D of [MPS-0738150]). Would that information have been of interest to Special Branch?

‘At the time I may have thought so, but…,’ he tailed off, unhelpfully.

PAUCITY OF MEMORIES

The Inquiry was then shown a report from January 1971 on a meeting of the central London branch of the ISC. There was mention of tarring and feathering incidents, and the speaker was very critical of the Republican leadership at the time.

Next came a report from the following month, February 1971, about a talk on ‘people’s democracy and the civil rights anti-apartheid movement Northern Ireland’ by Gerry Lawless.

This rung the lonely sound of a bell in Bailey’s memory, who said Lawless was ‘one of the very few names that I remember from then, because he was so active’.

Lawless was described as being involved in the ISC, as well as the IMG, and he additionally sometimes attended Red Circle discussion meetings.

Later in 1971, the Red Circle held a discussion entitled ‘why the Provisionals’. Bailey could not remember anything about what attendees thought of the speaker’s views.

ALDERSHOT

Finally on this theme, a report [UCPI0000008500] dated March 1972, a week or two after the bomb explosion at Aldershot army barracks which killed seven civilian staff. The ISC slogan at the time was ‘Victory to the IRA’.

Bailey was asked if he had any contact with the police investigating this bomb. He replied that ‘off our own bat there’s no way any of us would have had contact with a non-Met police force’.

Even within the Met, Bailey’s description made it appear that the sharing of information was left to managers, if it happened at all. He said that he only had contact with the SDS back-room staff, nobody else. Special Branch’s B Squad dealt with Irish matters, yet Bailey said he had no contact with them at all.

Bailey could not recall ISC members ever taking part in any acts of violence, or any public disorder at any demonstrations organised by the ISC. Again, he elaborated with a suggestion interpreting his lack of specific memory:

‘I’m sure something like that would have stuck in my memory and it definitely doesn’t’.

A few weeks after the Aldershot bombing, then-current and former members of the ISC had their homes raided. It may well have stemmed from Bailey’s reports on them; he professed not to know if that was the case.

BERNADETTE DEVLIN MP

His reports would mention whether or not events were attended by Bernadette Devlin, a young independent Irish republican MP.

According to Bailey:

‘if she was known to be going to attend any meeting or demonstration or whatever, then of course that would increase the likelihood of more people arriving at the demonstration’.

Interestingly, one of the files suggests that there was not yet a Special Branch file opened on Bernadette Devlin at this time.

He said he couldn’t elaborate beyond that because he merely reported, and what happened with the information he gave, or because of it, ‘was not my concern’.

Bernadette Devlin joins the growing list of MPs confirmed as having been spied on by the SDS, the unit that was supposedly formed to monitor those who would overthrow parliamentary democracy.

His reports also contained what was described as an ‘unflattering portrait of Irish solidarity groups’; a report of a conversations between another Northern Ireland political activist Eamonn McCann and others, and of McCann turning up late at a meeting.

SPYING ABROAD

Bailey attended the Conference for a Red Europe in Brussels in November 1970, having secured specific permission to travel abroad from his managers.

Bailey attended the Conference for a Red Europe in Brussels in November 1970, having secured specific permission to travel abroad from his managers.

As with the ISC conference in Birmingham a month earlier, Bailey says there was no direct contact between him and the other spycop who attended that conference. That other officer was officer HN326 ‘Doug Edwards’, who complained about the trip in his evidence last Friday.

Until last week, it had been thought that Peter Francis’ 1995 visit to an anti-racist gathering in Germany was the first time an SDS officer had gone abroad undercover.

VIETNAM SOLIDARITY CAMPAIGN

Although his name is attached to several reports on the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign, Bailey said he cannot remember attending any of their meetings.

He said he couldn’t comment on whether spycops would have been more likely to attend a meeting that Tariq Ali attended. Neither could he remember if he already knew the name Piers Corbyn in 1971.

BLACK POWER GROUPS

Bailey also reported on the Black People’s Defence, the Black Defence Committee, and Black Power. Asked if he had been directed to report on anti-racist groups he was, once more, at a loss to say.

END OF DEPLOYMENT

Bailey’s managers had instructed him not to join the International Marxist Group because it was ‘recognised as more of a political party’, something that doesn’t tally with the fact that his contemporary, ‘Doug Edwards’, was not merely a member of the Independent Labour Party but the Tower Hamlets branch treasurer.

Bailey’s undercover career lasted around two years, well in excess of the 12 month maximum stipulated in a document written by SDS founder Conrad Dixon. Bailey can’t understand how 12 months would be enough time to gain the trust to make detailed reporting worthwhile, and can’t imagine many had so short a deployment unless something went wrong. He says he was unaware of the supposed limit until the Inquiry told him about it.

He suffered from headaches, nosebleeds, and migraines, which he attributes to the stress of his job. thought to be caused by stress. He recalls negligible support in the macho world of the spycops, saying ‘you got on with it’.

PDF of the accompanying written witness statement of HN340 ‘Andy Bailey’/ ‘Alan Nixon’

COPS will be live-tweeting all the Inquiry hearings, and producing daily reports like this one for the blog. They will be indexed on our UCPI Public Inquiry page.