UCPI Daily Report, 12 Nov 2020

Tranche 1, Phase 1, Day 9

Tranche 1, Phase 1, Day 9

12 November 2020

Evidence from:

Officer HN 329 aka ‘John Graham’

Ernest Tate, anti-war & Marxist activist (written statement read in full by Nick Stanage)

Officer HN 218 aka Barry Moss (summary of evidence)

Officer HN 334 aka ‘Margaret White’ (summary of evidence)

The morning was taken up by that first police witness, officer HN 329 aka ‘John Graham’. After many years of waiting, we finally heard a former undercover officer speak from the witness box. Unfortunately, most people could not see or hear as only a near-contemporaneous transcript was broadcast.

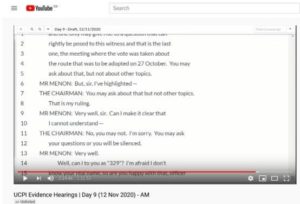

‘YOU WILL BE SILENCED’

With the very first police witness giving evidence at the Undercover Policing Inquiry, barrister for the victims of spycops Rajiv Menon QC wanted to ask a series of questions. But the Inquiry’s Chair, Sir John Mitting, cut him off lest it be stressful for the spycop. When Menon tried to debate the matter, Mitting told him to obey or ‘you will be silenced’.

This outburst was just an unruly version of what we’ve seen from Mitting all along – the prioritisation of the comfort of spycops over the desire of victims and the public to know the truth. He ignores the fact that this is an inquiry into police wrongdoing and is clearly affronted at the impudence of those who would challenge a police officer.

Screenshot of UCPI live transcript with Chair telling Rajiv Menon QC: ‘You will be silenced’

Most of the afternoon was devoted to lifelong anti-war and left-wing activist Ernest Tate, on of the organisers of the 1968 demonstrations against the Vietnam War that sparked the founding of the Special Demonstration Squad and, as such, events to which the Inquiry is giving a lot of attention.

At the end of the day, there were summaries of the statements from two former spycops who aren’t giving evidence in person, then brief details about the careers of six deceased officers.

Officer HN 329, aka ‘John Graham’

[Note, throughout this we refer to the officer by his cover name, John Graham].

Graham principally spied upon the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign (VSC) of whom protest organiser Tariq Ali’s testimony we heard yesterday.

The questions were put by David Barr QC, Counsel To the Inquiry. He began by asking him some questions about joining the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS). Specifically, he was asked whether he volunteered or if he volunteered by someone else. He replied that he thought he was told to join the new unit in 1968.

He had joined Special Branch early on, initially working for the ‘naturalisation inquiries’ section, which gave him insight to the sort of reporting Special Branch generally wanted. Senior officers would check over work to ensure nothing ‘irrelevant’ was included.

Prior to joining the SDS, he also worked in ‘C’ Squad in Special Branch – responsible for monitoring communists and this involved ‘normal’ plain-clothes Special Branch work with no undercover name or persona used.

UNDERSTANDING SPECIAL BRANCH

There were a number of questions that Graham could either not help with or gave unhelpfully vague answers. These included what Special Branch’s definition of extremism was.

He was a little more helpful on Special Branch’s duty regarding the ‘Security of the State’ – or at least his earlier written statement was. There he suggested that by collecting information covertly, Special Branch would be able to find out about any violent intent on part of protesters.

Expanding on this line, Barr again referred to the officer’s written statement, eliciting about the Special Branch’s role vis-a-vis policing political groups:

‘I understood the role of Special Branch to be carrying out enquiries concerning the security of the State, in other words gathering intelligence on activities that sought to undermine the status quo, the government of the day and the political establishment’.

The conflation of national security with the convenience and policy of the government has always been a central factor in what spycops do.

TRAINING & ACTIVITIES

On training, he explained that his time in Special Branch had already given him a good idea of what was expected, and what kind of information they would have been interested in collecting. For instance, they would have been interested in personal details, any distinguishing features. It also included info about the dynamics of the group he was reporting on and any analysis that he thought useful. He left any ‘filtering’ of the information to someone else.

Graham explained that there wasn’t much of a difference between normal Special Branch duties and those within the SDS in terms of attending political meetings. As part of the ‘general inquiries’ section of Special Branch, he would attend in plain clothes.

Once he joined the SDS, he would just wear ‘nondescript clothing’. He said that sometimes people who were dressed smartly might be regarded with suspicion (and asked to leave a meeting) but ‘if you were scruffy.. nobody bothered you’.

A REVOLUTIONARY PERSUASION

Graham infiltrated various VSC branches in North West London, attending meetings in Camden, Hampstead, Kilburn, and Willesden. He added that the Camden group was ‘considered prominent as it contained Geoff Richman’. (Geoff and Marie Richman were prominent in the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign itself, and Geoff, a medical doctor, was a member of the Socialist Medical Association.)

Graham describes the Richmans as ‘nice people’. A question might have been put here whether this made the officer feel uncomfortable in spying on them. However, there was no hint of regret or remorse at any point in Graham’s oral hearing.

Barr asked Graham about the revolutionary sentiment he found in Camden that was apparently so in need of infiltration and monitoring:

Barr: You describe the Camden VSC in terms which suggest they were revolutionary but they were not going to use violence to try and achieve their ends. Could you describe in what sense you understood them to be revolutionary?

Graham: Well, they – they wanted to change the government.

Barr: And if they were not going to use violence, how were they going to seek a change of government?

Graham: To try and persuade people to their point of view.

Graham said that the Camden VSC group once did a performance in a market, but apart from that they only really went on the big demonstrations. None of the groups he spied on tried to do anything secret, he said.

He confirmed that SDS boss Chief Inspector Conrad Dixon sometimes attended these VSC meetings too. Most of the time Graham was alone at these meetings. However, if more than one SDS officer was in the same meeting, they would play it by ear, and maybe not even acknowledge each other saying.

A PUBLISHED AUTHOR

Next a publication called ‘Red Camden’ (UCPI0000007701) was referred to. This was the journal of the Camden VSC. In one 1969 issue was an article which was attributed to the name ‘John Grahame’, which spoke of him attending a Vietnam Solidarity Campaign Working Committee meeting, where he was expecting political infighting.

Article by spycop ‘John Graham’, 8 June 1969 issue of Red Camden newsletter, a publication of the Camden Vietnam Solidarity Campaign

Graham had no recollection of writing it, but said it was possible that it had been written by Dixon or another SDS colleague, and his name added to it. A clearer copy can be found on the Undercover Research Group’s profile of John Graham.

Another document referred to was a report from a VSC meeting at Conway Hall on 17th September 1968. Barr noted that this was attended by at least seven members of the SDS. As well as John Graham, this list included squad head Chef Inspector Conrad Dixon, DI Saunders, DS Wilson, DS Fisher, DS Creamer and DC Moss.

The obvious question of why so many police attended the same meeting, to which Graham could only reply:

‘It may have been a question of, that there was nothing else on, so people felt that they ought to be doing something.’

Even among the extreme stories of the spycops, this was an extraordinary moment.

Last week police lawyers emphasised that the SDS was established because 1968 was a volatile time with feral subversives everywhere. Today we’re told seven of them went to the same anti-war meeting because of a lack of work. They’d rather spy on the undeserving than not spy at all.

Graham also explained that this might have made it easier for the undercovers’ to remember stuff (as they couldn’t make any notes during the meeting) and to identify attendees (who were numerous). This explanation doesn’t ring true, as if it were it would be common practice.

Graham was asked if he and fellow SDS officers would take part in ballots at meetings, and thereby influence the results? Not understanding the significance of this obvious interference with the political process, Graham just said he voted on motions without giving it much thought:

‘it’s just a question of sticking your hand up with the majority once you knew which way the vote was going to go anyway.’

The next meeting mentioned involved the Anti-Imperialist Solidarity Movement. In this context, Graham was asked why he felt the need to record the ethnic origin of attendees, or use the word ‘coloured’ to do so? Only answering the second part of the question, He said that it was common to do so at the time.

ACTIVE PARTICIPATION

Barr then moved on to the officer’s attendance at a much smaller meeting, of the VSC ‘working committee’ – by this time he had been embedded in the group for many months, and so was able to access these less public discussions, that took place in private homes.

In his first written statement, Graham states that none of these meetings were ‘closed’ – you just had to have had attended a previous open meeting to know about it. He claimed not to recall much about his participation in these meetings – said that he probably just went along with the majority opinion as to the most ‘sensible and safest tactic’ and that no guidance was given about meetings in private homes, or in travelling outside of the Met’s jurisdiction.

MOBILE ESPIONAGE

On this, he said he said he attended an event in Sheffield in May 1969. When asked if it was common for SDS officers to travel to other areas, he said he had ‘no idea’ as ‘everyone was working separately in their groups.’ This illustrates the lack of day-to-day oversight of these early deployments.

A protest of particular note in the evidence was an early 1969, Australians and New Zealanders Against the War in Vietnam organised a meeting at Australia House then marched along the Strand in London to the Savoy Hotel, where the Australian prime minister was staying.

Graham remembered that event as he was punched in the ribs by a security guard while being ejected. He expanded on this, saying the rest of the group had got up to shout in defence of one guy who was being ejected from the building, so Graham felt he had to partake to maintain his cover saying: ‘I thought I better get to my feet and I remember saying ‘let him speak’. He was grabbed and dragged out and recalls he pretended to resist.

DINNER DATES & GHOST WRITERS

The next questions were about Graham inviting a woman activist out to dinner, and going through on it even though by this time he was aware he was being withdrawn as an undercover officer. He said he couldn’t remember why he had done this, or really anything about it at all, though his statement noted he hadn’t wanted to let her down. He denied there was any sexual motivation for the date. This still leaves the puzzle of why he invited her out in the first place, or why he did not cancel it.

When asked about the possibility of signing his name to any reports which he hadn’t written, which had been written by another undercover, Graham said in general ‘I wouldn’t have signed anything I didn’t know to be true.’

More then was asked about the ‘ethos’ of the SDS – ‘were you open with each other or secretive with one another’, to which he replied that ‘In the main, I suppose we were open’. On the stresses and strain of being undercover, Graham was blasé, neither finding his deployment stressful or felt that he needed any special support.

SIMPLY THE BEST

Finally, when asked for his view of those early days of the SDS, Graham said:

‘The original group, from Conrad Dixon down, were the finest representatives of Special Branch. And they were excellent officers who did exactly the proper job.’

This was the end of David Barr’s questions, which were thought unsatisfactory by many watching as issues raised were not followed up in the search for more firm answers.

‘YOU WILL BE SILENCED’

Tariq Ali’s barrister, Rajiv Menon QC, then rose, requesting permission to ask supplementary questions. He wanted to ask Graham about:

1) the political motivations of the VSC in those early days;

2) the selection and targeting of the VSC, and some more detail about what the officer was told to do;

3) the general methodology of the SDS, and what happened at these near-daily or daily meetings at the unit’s ‘safe house’ (the rented flat used by the SDS away from New Scotland Yard to spend their daytime and write up reports, as the political meetings they spied on tended to take place in the evenings)

4) what information the officer had collected that made a difference, particularly resulting in a lower level of public disorder in the October 1968 Vietnam demonstration than there had been in March;

5) the use of ‘Box 500/MI5’ (how much intelligence was passed to the security services)

6) and finally, some questions in relation to one of the documents already exhibited – the meeting attended by 7 SDS officers.

Menon added that the early finishing of Barr’s questions meant there was sufficient time before the next witness. What happened next was truly shocking. Mitting refused Menon’s request, saying it would repeat questions that Barr blatantly had not asked, and that it may be uncomfortable for Graham. Mitting’s words were:

Mitting: ‘That may be so, but I have to keep order in the proceedings and to ensure not merely that this witness is not troubled by questions that have already adequately been covered by Mr Barr and by his statement and by the documents, but also that this does not set a precedent for future such requests.

‘Of the seven topics that you have given to me, one and one only may give rise to a question that can rightly be posed to this witness, and that is the last one: the meeting where the vote was taken about the route that was to be adopted on 27 October. You may ask about that, but not about other topics.’

Some what perplexed, Menon began to ask for clarification:

Menon: ‘But, sir, I’ve highlighted -‘

Instead of giving him a civil reply that the point deserved, a visibly agitated Mitting interrupted:

Mitting: ‘You may ask about that but not other topics. That is my ruling.’

Menon accepted and sought to clarify, saying:

Menon: Very well, sir. Can I make it clear that I cannot understand –

At which point Mitting cut straight across him with a threat of censorship:

Mitting: No, you may not. I’m sorry. You may ask your questions, or you will be silenced.

This outburst from Mitting was met with shock, but for many core participants is symptomatic of the general hostility and downright contempt with which the Chair has treated the non-state participants in both his decision-making and his attitude throughout the Inquiry. Campaign Opposing Police Surveillance have since issued a media release questioning Mitting’s behaviour.

A PERMITTED QUESTION

The only question that Mitting was prepared to allow was the one about the VSC meeting when a vote was taken about the route of the 27 October Grosvenor Square demonstration. Menon asked the officer about the voting that took place at this meeting. His explanation (earlier on) was that if he hadn’t voted, he would have stood out like a sore thumb. So he must have put his hand up but has no recollection of it.

When asked whether this vote discussed later on, back at the flat, Graham claimed not to remember how he’d voted, or any discussions with other undercovers afterwards about how they had voted. He also said that they would have all gone off on their separate ways, and that other SDS officers who were normally back office staff wouldn’t usually have come to the flat anyway.

Asked about whether the information the police spies gathered would have made it into other officers’ reports, he answered ‘it would have assisted at some stage with identifying people’.

After the stormy and frustrating end to the questioning of the first police witness, the Inquiry broke for lunch.

The accompanying first written witness statement of officer EN329 and the second written witness statement of officer EN329

Ernest Tate

Political activist

(written statement read in full by Nick Stanage)

Ernie Tate & Jess MacKenzie

Ernest Tate was unable to give evidence in person, his statement was read for him by Nick Stanage QC.

Tate was born in Belfast in 1934. He emigrated to Canada at the age of 21 and worked in mechanical engineering.

Politically active all his life, Tate has written a memoir of his activism in the 1950s and 1960s, relating to his time in the International Group (a section of the Fourth International, as founded by Leon Trotsky in 1938) which, in Britain, became in the International Marxist Group (IMG).

Tate was in Britain for almost five years between 1965 and 1969, and in that time was heavily involved in the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign (VSC), which was set up in 1966.

Returning to Canada in 1969, he became involved in the trade unions and for many years was Chief Steward and Vice President of a major local of the Canadian Union of Public Employees. He is now retired, and living in Toronto.

ERNEST TATE, FILE 402/66/451

The Undercover Policing Inquiry had sent Tate a ‘Witness Pack’ of 23 Special Branch intelligence reports dated between 8 February1965 and 3 March 1969 in which his name is mentioned. The Inquiry asked him to answer questions about his activity in general and the documents in particular.

The reports were based on on activity of officers of the Metropolitan Police Special Branch’s undercover political unit, founded in 1968 as the ‘Special Operations Squad’ (SOS), and re-named the ‘Special Demonstration Squad’ (SDS) around 1972-3.

Tate’s Special Branch ‘Registry File’ has the reference number 402/66/451, which indicates it was opened in 1966. Such reports were routinely copied to MI5. Like many others targeted by spycops, Tate’s full file remains ‘Top Secret’. The fact that he left the UK over 50 years ago and the groups he was in no longer exists make no difference to the secrecy.

The few reports given to Tate are only a fraction of the secret surveillance files held on him, the International Marxist Group [RF 400/58/152] of which he was a full time organiser, and the

Vietnam Solidarity Campaign [RF 346/65/15], in which he was was also heavily involved.

FEW FACTS, FEWER ANSWERS

The Inquiry has made it harder for Tate to contribute, because it has chosen not to let him see any of the Witness Statements made by any of the SOS officers who spied on him, nor any statements from managers or an appropriate officer who could provide evidence on behalf of a deceased officer.

Additionally, he hasn’t been shown any photographs of officers in their undercover guise, save for one of Chief Inspector Conrad Dixon.

The undercover officers who have been identified as having spied on him are:

• TN0039 Chief Inspector Conrad Dixon

• HN299/342 ‘David Hughes‘ (despite the Inquiry website saying he was only deployed from 1971, more than a year after Tate had left the country)

• HN321 ‘William Paul “Bill” Lewis‘

• HN329 ‘John Graham‘

• HN326 ‘Douglas Edwards‘

• HN332 whose details do not yet appear on the Inquiry website

Conrad Dixon, founder of the SDS

The path to clarity is further obstructed by the failure of the Inquiry to ask the Metropolitan Police to provide Position Statements, which would set out exactly why the SOS was set up, what its operational parameters were, and why it was necessary to begin more intrusive surveillance, including forming intimate relationships with targets.

Tate presumes the State will argue that this clear breach of the basic human right to privacy was justified due to a threat of serious violence from those groups or individuals spied on. In which case, the Met should have to explain why the SOS was allowed to continue to operate after the 27 October 1968 demonstration against the Vietnam War had passed off largely peacefully.

Tate completely refuted the notion that he, the VSC, or the IMG, threatened violence, especially serious violence. Equally, he rejected any suggestion that any of them deserved to be targeted because infiltration would allow the police to monitor others.

He asserted that there is no justification for the gross intrusion by the police into people’s private lives on the basis that a person’s, or group’s politics is frowned upon by the State, unless there is a real, not fanciful, threat of serious violence. The UK had been a signatory to the European Convention of Human Rights for many years by the time the spycop unit was formed, and the Article 8 of the respect for privacy, private and family life, should be applied to any judgment about the legitimacy of its actions.

SECRECY WITHOUT END

Special Branch records from 1887 onward are subject to almost complete secrecy regardless of age. A few documents were obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request by journalist Solomon Hughes 10 years ago in an attempt to establish what happened in 1968, and these were put onto the Special Branch Files Project website.

The advent of the Inquiry has seen the release of some spycops’ documents, but it’s a sliver of what was created. It means it’s almost impossible for Tate and other core participants at the Inquiry to counter any narrative given by the Home Office and the Metropolitan Police

Tate then turned to the specific questions the Inquiry had asked him, saying:

‘It is clear in my mind that these questions focus very narrowly on the issue of violence, hence it appears to me that this will be the justification used by those in charge of SDS throughout the period…

‘The other major interested parties, the Metropolitan Police and the Home Office who oversaw the wrongdoing of SOS officers, have full access to every file they want’

He pointed that, in contrast to the clandestine and secretive nature of the British State, he has nothing to hide. The Inquiry, the Police and members of the public can read what he has written about his activities in his two-volume memoir, Revolutionary Activism in the 1950s and 60s, Ernest Tate, A Memoir’ (Volume 1 Canada 1955-65, and Volume 2, Britain 1965-1970).

Tate was asked to clarify his role in the VSC. He was one of its founders in June 1966. He was a member of its National Council and its executive committee, from that date on until April 1969. The executive committee, a sub-committee of the National Council, provided leadership to the VSC between National Council meetings and was responsible for its national functioning on a day-to-day basis. Beyond that, Tate publicly wrote and spoke for the VSC.

Tate was asked to clarify his role in the VSC. He was one of its founders in June 1966. He was a member of its National Council and its executive committee, from that date on until April 1969. The executive committee, a sub-committee of the National Council, provided leadership to the VSC between National Council meetings and was responsible for its national functioning on a day-to-day basis. Beyond that, Tate publicly wrote and spoke for the VSC.

A million people perished in the Vietnam War, including 50,000 US soldiers, most of whom were teenagers. Tate explained that the VSC aimed to build a solidarity campaign with the Vietnamese against the American aggression, calling for its immediate end and the withdrawal of all of American forces, and the end of British collusion with the Americans. It also called for support for the Vietnamese National Liberation Front.

It sought to achieve this through building broad united-front coalitions of like-minded organisations and individuals to create mass mobilisations on the streets against the war.

NOTHING TO HIDE

There was no vetting of members, they merely had to agree with the broad aims, provide funds and attend meetings. The political debates were quite open, and as a result, at the founding conference in 1966, a large number of Maoist delegates withdrew to a separate location and formed the rival Britain-Vietnam Solidarity Front (BVSF). The anarchists also held separate conferences, as they wanted to be clear they were ‘neither Washington nor Hanoi’.

There was no secrecy of any kind. All VSC business and policy meetings were open to all members, though not to the general public. They knew the police were interested in what they were doing, but because none of it was illegal they didn’t worry about infiltration. They specifically warned members against pointing fingers of suspicion at anyone, knowing how that had been used in other groups in the past to divide and destroy the movement.

The Inquiry asked if there was violence planned for, or witnessed at, the March 1968 demonstration.

Tate unequivocally affirmed that there was none planned. He described how the march, tens of thousands strong, tried to enter Grosvenor Square, they were met by hundreds, if not thousands, of uniformed police, many on horseback, who in aggressively confronted them in order to prevent anyone getting near the American Embassy. Violence erupted with many police and demonstrators injured and/or arrested, the blame for which Tate lays firmly with the police.

INTERNATIONAL MARXIST GROUP

Tate also described the IMG and his role there. He helped to organize the group and was a member of its National and Political Committees. His primary loyalty was to the IMG, rather than the VSC. The IMG was primarily responsible for the creation of the VSC, its members functioned as an open caucus to prepare for its various conference and activities.

He confirmed that the IMG was a revolutionary group, and gave a series of refreshingly direct and concise answers.

Inquiry: Did the IMG believe that revolution would, or might, require the use

of force?

Tate: Yes.

Inquiry: Did the IMG believe that force should be used to bring about revolution in 1968-1969?

Tate: No.

Inquiry: Did the IMG believe that public disorder would advance its cause?

Tate: No.

Inquiry: Did the IMG believe that breaking any laws was justified or necessary to advance its cause? If so, which laws and for what purposes?

Tate: The IMG did not believe in breaking the law, but if a particular law was oppressive or dangerous to our democratic rights, and there was mass opposition in society to it, then the IMG might have explored ways to challenge that law.

Tate declared the infiltration of the VSC and the IMG and scandalous:

‘It reveals how far democratic tights in Britain have been abused over the past fifty years. It has become the norm, it seems to me, for the State to put the boot to anyone it doesn’t like. If you’re a socialist or Marxist or someone who has different ideas about how the economy and society should be organised, should we expect dirty tricks from those who are supposed to protect us?’

A HANDFUL OF FILES

The Inquiry then ran through the documents it had revealed to Tate, and asked for his opinion on their accuracy. He criticised the selection of documents as a ‘bizarrely selected and highly partisan package of material’ that had the huge absence of the great bulk of contemporaneous relevant documents that must have been created. What have the Met and the Home Office got to hide?

‘if this is really meant to be a Public Inquiry then the public – journalists and academics, historians and those of us who were involved at the time – should be allowed to see the material.’

Tate went through the documents methodically, giving a facinating insight into how much the spycops targeted one person. The documents included:

MPS-0739885: This was a report of a meeting on 8 February 1968.

According to Special Branch officer “David Hughes’ (HN299/342), it was an open public meeting attended by about 70 people at Toynbee Hall in Whitechapel to show the film ‘American War Crimes in Vietnam’. One of the future protests mentioned was against Dow Chemical in Wigmore Street, London, the manufacturers of the notorious substance napalm which burnt people alive and was being extensively used by American forces in Vietnam.

June 8, 1972: Kim Phúc, (centre left) running down a road naked near Trảng Bàng after a South Vietnam Air Force napalm attack

What is interesting is that this routine report is prior to the formation of the covert SOS/SDS unit. This shows that Special Branch were easily able to access the meetings and report on everyone without the need for deeper-cover infiltrators.

Tate highlighted the lack of any witness statement from ‘David Hughes’ in his Witness Pack, in which ‘Hughes’ might have explained the difference between his routine Special Branch duties in monitoring these meetings and his later doing the same thing within SOS/SDS.

No photograph of this officer, who was then presumably in his twenties, has been supplied to assist Tate in trying to recall him and his activities. But ‘Hughes’ has been granted anonymity at the Inquiry.

In a decision typical of the orders that are allowing the overwhelming majority of spycops to get away unnamed, the Inquiry ruled that:

‘publication of his real name would risk unwelcome media attention and the attention of those who maybe disposed towards him within his small community… The interference with his right to respect for his private life which it would risk would not be justified’.

Tate wryly replied:

‘I am pleased to see that the Inquiry is underlining the importance of the right to respect for private and family life. and I trust this same important right will be afforded to the people who were spied on when and if any judgments are reached concerning the gross interference with this right as practiced by the Metropolitan Police Special Branch and others.’

MPS-0739886: Report of a private meeting of 35 people on 15 February 1968, though ‘David Hughes’ was there again to report on it which, said Tate, indicates that it would have been an open meeting for anyone who wanted to be involved in VSC activities.

The report says that towards the end of the meeting some people present said they intended breaking windows at the US embassy and were prepared for a ‘punch up’ with the police; others said they wanted a sit-down protest.

Tate responded:

‘To be clear, VSC policy was always non-violent, we were only too aware that the violence was a particularly strong attribute of the State. The officer’s assessment that a ‘fair amount of violence’ could be expected at the forthcoming solidarity demonstration in March 1968 was not an assessment I would have shared at the time.’

MPS-0730911: This report of the 17 March 1968 demo was submitted by the Special Branch

Commander to the Director of Public Prosecutions. This means that, rather than gathering intelligence, it was explicitly prepared for the sake of supporting prosecutions by the State, presumably of the VSC leadership.

It is surely unusual that Special Branch officers (including the later head of SDS, Chief Inspector Conrad Dixon) were tasked to take ordinary witness statements from members of the public. It would help to have a witness statement explaining the reason for this report too, but there is none.

It details two particular incidents that resulted in the confrontation with police in Grosvenor Square, firstly the initial refusal to allow the letters of protest to be delivered to the Embassy, as had been agreed with the Met beforehand; and secondly the fact that the march was blocked by police at the corner of North Audrey Street, in such a way that the demonstrators were very compressed and so burst forth.

This created panic among the authorities which, in turn, led to the formation of the SOS/SDS in the summer of 1968. And yet the answer to this militancy is given in a leaflet enclosed with the report, which described how the mood and temper of the demonstration was determined by the American aggression, and that it was impossible to remain calm and peaceful before the barbarism of American aggression in Vietnam.

MPS-0722106: This report of 2 April 1968 by Chief Inspector Conrad Dixon, signed off by Chief Superintendent [name redacted, presumably A Cunningham] is another report into the March

1968 VSC demonstration.

Noting that the author was the founder and head of the spycops unit, Tate mused:

‘I think that Conrad Dixon is an important player in the history of the SDS and it is a shame that he is now deceased as I am sure he would have plenty to say. In his 1999 obituary in The Times it is stated that he was the leader and founder of SOS, having been born into an army family, educated at Oxford and joined the Royal Marines. At Special Branch he apparently “specialised in anarchists, Trotskyists and anarcho-syndicalists”.’

When setting up the unit, Dixon had legendarily asked for men, a budget, and a free hand. Tate homed in on this point:

‘I would like to emphasise the words “a free hand” as this suggests a complicity at higher levels with the SDS being allowed to thrive in a culture that broke the rules. I also note that his obituary is quite open about his role in SDS, in contrast to the institutional secrecy of the Metropolitan Police.’

Though Dixon’s report suggests there were proposals for violent action at the demonstration, he also said:

‘it is not possible to use these sources for evidential purposes, and no evidence of violent intentions was obtained by police officers who gained entry to some of these closed meetings.’

Tate laid the contradiction wide open and, having already shown that Special Branch had infiltrated the VSC, speculated that we may have found the real reason the spycops unit was established:

‘This can only mean that there are existing Special Branch reports (perhaps filed in RF 361/68/12 Ad Hoc Committee?) that detail these supposed discussions. I would like to see them… This all sounds like make-believe; Cl Dixon obviously knew what his masters wanted to hear. One wonders if the future creation of SOS/SOS was not out of desperation to try and find this supposed ‘evidence’ that was so sorely lacking.

‘The truth is there was not the slightest evidence that VSC planned any form of violence. VSC only believed in lawful resistance to police violence (i.e. lawful self-defence). It seems clear to me that this Special Branch report is obviously expressing and reflecting the political prejudices of the British government of the day and the police, it is utterly self-serving and the Inquiry should beware of placing too much weight on it.’

Tate said the Inquiry should examine the dossier compiled by the National Council for Civil Liberties, that provided independent observers on the day of the demonstration. This dossier is referred to by Peter Jackson MP in his speech to parliament on 4 April 1968. His account supports Tate’s.

MPS-0741312: Documents, placed in the files in July 1968 for Chief Inspector Dixon to action, are the first that are dated after the creation of the Special Operations Squad. They include copies of the minutes of a VSC Executive meeting held on 5 July 1968, and the VSC National Council on 10 July

1968. There is nothing in these meetings or minutes that was secret.

MPS-0738746: A report of a VSC meeting at Conway Hall on 20 August 1968, seemingly from Detective Sergeant Roy Creamer. Tate noted that Creamer is absent from the Inquiry’s list of officers. Who exactly was he?

Since the Inquiry started, it has posted this report and one other document by Creamer, as well as a photo of him that it did not send to Tate in its Witness Pack.

The report is was marked ‘Box 500’, meaning it had been copied to MI5. Tate notes that the Registry File numbers have been redacted, as well as what is presumably the word ‘Secret’ at the top of the document.

MPS-0730063: This is another significant report, dated 10 September 1968, by the head of the new SOS unit, CI Conrad Dixon. It written up just a few days after the VSC National Council meeting in Sheffield on 7 September 1968 – about which there is inexplicably no report disclosed – which confirmed the route of the October demonstration.

Tate described it as:

‘an utterly superficial and very opinionated police summary of contemporary British radicalism… very distorted, but just what I would expect from a secret policeman. His characterization of Tariq Ali as a “mob orator” and Ralph Schoenman as a “notorious agitator” and the general tone of the report suggests a policeman with a deep loathing of his subjects: he is perhaps aware that his career is better assisted by producing alarmist reports of this nature for his superiors than more carefully considered ones: the creation of SOS had to be justified.’

‘As for the supposed rumours or reports about the acquisition of (fire)arms and the preparation of Molotov cocktails, these are the product of a febrile imagination; even he admits have no evidential basis. He even accepts that the anarchist conference of 8 September 1968 in London condemned ‘senseless violence’.

‘I believe that there was a deliberate State tactic to foment public hysteria to frighten people away from joining future demonstrations – notwithstanding that the increased publicity may have actually had the opposite effect.’

MPS-0738815: A report of a meeting of the NW London Ad Hoc Committee on 11 September 1968 at the Friends House in NW3. Two officers were present, CI Dixon and a Detective Inspector HN 332 whose identity has still not been disclosed. Tate has no memory of the meeting.

UCPI0000005782: A report of PC Barry Moss and CI Dixon dated 19 September 1968 attaches a report, said to be written by Tate, on the Revolutionary Socialist Students Federation. Unfortunately the copy is almost completely illegible and impossible to read. Whatever was in it, it was sent to MI5.

MPS-0722099: A report on a meeting of 32 people of the VSC Lambeth branch at the ‘Duke of Cambridge’ pub on 26 September 1968, authored by ‘William Paul Lewis’.

Tate agrees with the report detailing his attempts to secure the support of the working class and trade unions for the demonstration. As for ‘Lewis’ himself, Tate observed that the Metropolitan Police applied in July 2017 for his cover name to remain anonymous, despite the fact that this is meant to be a Public Inquiry.

The application said that he did not steal his identity from a deceased child, but aside from this we know nothing. Again, the absence of the officer’s statement in the Witness Pack has constrained Tate’s ability to comment.

The Inquiry’s decision to grant ‘Lewis’ anonymity has some curious elements:

‘It is likely that disclosure of his real name would prompt intense and unwelcome media interest in him and so would give rise to serious interference with his and his family’s right to respect for their private life under Article 8 of the European Convention which would not be justifiable under Article 8(2). Closed reasons accompany this note.’

Why would the media be especially interested? What are the ‘closed reasons’ that we’re not allowed to know?

MPS-0730096: Another report by CI Conrad Dixon, this time dated 3 October 1968 and described as a ‘regular weekly report’ on the preparations for the national demonstration three weeks hence. Tate is mentioned as an IMG member and member of the VSC executive.

Interestingly, this document was made public in 2008, obtained by the journalist Solomon Hughes – but paragraph (b) was redacted for some reason; it mentions a supposed attack by London School of Economics (LSE) students on the Stock Exchange and an occupation of the LSE itself.

According to his Times obituary in 1999, Dixon was involved as an undercover officer in that occupation on 25 October and seized the telephone exchange. This is presumably the reason for the redaction.

Dixon said students have provided the bulk of the support for the VSC demonstrations thus far, and ‘their behaviour on demonstrations is largely spontaneous’.

Tate concurred with this assessment, adding that it actually proved his point:

‘there was never any plan for violence from the IMG or the VSC, rather the complete opposite, we wanted a huge but peaceful demonstration. Insofar as the Maoists wanted a more militant approach by confronting police in Grosvenor Square, we in the VSC were opposed to this and the three Maoist-controlled VSC local branches had been disowned by the National Council for this reason.’

Dixon says the Maoist contingent was said to number no more than 100 people. He concludes that it is the people who are not represented on the VSC – anarchists, Maoists and ‘foreign elements’ – who are most likely to use violence and be hostile to the police. In saying this, Dixon completely undermines the supposed reason for infiltrating the VSC at all. If it wasn’t about violence, it must have been about politics.

When all this is considered, it’s pretty clear that police and organisers only expected a tiny number of people who were desirous of a clash with the police, and any such situation that arose would be largely spontaneous. All that undercover policing made not the slightest difference to the

manner in which events transpired on 27 October 1988.

The Times obituary of 1999 gives Dixon credit for advising that the police lines needed to be thicker to prevent demonstrators breaking through. It did not take undercover police, or indeed any police at all, to come up with that idea, it’s just obvious crowd control stuff.

MPS-0730091: This is Cl Dixon’s next weekly report, dated 16 October 1968, and signed off by Chief Superintendent A. Cunningham. It notes both Tate and his partner Jess MacKenzie as being prominent in VSC affairs.

MPS-0730093: This appears to be the definitive police report of the 27 October 1968 VSC demonstration, submitted by Chief Superintendent A. Cunningham.

Tate refuted the claim the VSC was ‘to a considerable extent responsible for the violence which occurred at the demonstrations in London on October 1967, March and July 1968’, and wondered why, if the July demo was of interest to the police, no documents have been shown to him:

‘It is unfair to characterize the approach of the VSC and myself as simply ‘paying lip service’ to

the concept of an orderly demonstration. This is what we wanted. We did disagree with the Maoists and excluded them. His statement that ‘the majority were well disciplined and acted in an orderly manner under the direction of the VSC marshals’ is correct and rather belies his earlier dire warnings of considerable public disorder being likely.’

MPS-0731634: A report on an IMG meeting of about 30 people held in ‘The Earl Russell ‘ pub on Sunday 3 November 1958, to discuss the political situation in Northern Ireland, where Tate is from. ‘William Paul Lewis’ wrote the report, and had presumably become an IMG member. A copy of this report went to MI5 and another copy to ‘B Squad (“Irish Extremism”).

Tate commented:

‘The context was that the first Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) march had

taken place on 24 August 1958 in Dungannon, drawing 4000 people. This passed off peacefully, but on 5 October 1968 another NICRA march was attacked by police officers of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), this was the start of what became known as The Troubles.’ Once again, the serious violence was from the police not the protesters.’

MPS-0730768: A report by Cl Dixon of a meeting of the VSC at Conway Hall on 11 November 1968. 100 people came to discuss the 27 October demonstration.

Further undercover officers were present:

TN0034, a Detective Sergeant;

HN321 ‘William Paul Lewis’;

HN329 ‘John Graham’;

HN326 ‘Douglas Edwards’.

No witness statements of any of these officers were included in Tate’s Witness Pack.

Tate then returned to the Inquiry’s questions. They asked, having seen the reports, what additional access to the VSC would the use of undercover police officers, as opposed to plain clothes detectives, have given to the police?

Tate said, ‘I don’t know, It probably made it easier for them to steal membership lists.’

The Inquiry went back to the report dated 30 July 1966 (MPS-0738693) in which Tate is described as a ‘dove’ on the question of violence by comparison to the ‘hawk’, ‘Albert’ Manchanda.

Tate’s response was at once exasperated and dismissive:

‘This is gossip I have never heard before. My disagreements with Manchanda were fundamentally political, about what should be the program of the VSC. I did not know at that time what his views were about violence in relation to the Vietnam protest movement, I never ever discussed this issue with him. I never trusted him. He led a splinter group which tried to wreck the founding conference in 1966. The Maoists formed a separate organization, the Britain-Vietnam Solidarity Front (BVSF).’

The Inquiry also highlighted a report’s claim that ‘the more cautious representatives of International Socialism and International Marxist groups paid lip service to the vision of a peaceful demonstration’.

Tate rebuffed the sneering insinuations:

‘This is gossip from sources that were not involved in the campaign. We in the leadership of the VSC and the Ad Hoc Committee, were totally committed to peaceful demonstrations, and if violence took place, it was incidental and outside of our control. This is why we did not go to Grosvenor Square on 27 October 1968. It was mainly a peaceful event, much to the surprise of the police, who by that time had frightened the authorities into a state of panic.

‘I and the rest of the leadership of the VSC suspected the Maoists would make an effort to hijack the demonstration as it made its way past Trafalgar Square; that’s why we stopped the demonstration in the middle of the street when they tried to divert it to Grosvenor Square. We effectively policed our own demonstration.’

Responding to a list of tactics which spycops regarded as having been suggested at branch, but not national level, Tate was equally disparaging:

‘This is the product of the fevered imagination of the security services who seemed to be out to frighten their superiors and the Wilson Labour Government. It looks like every little piece of scary information from whatever source, or whatever they invented, was used for this purpose.

‘We, the organizers of the demonstration, wanted the largest mobilisation possible, one to which the participants could bring their families without the fear of being exposed to violence. That’s why the Ad Hoc Committee adopted a march route that ended up with a rally in Hyde Park. What happened on that day highlights the wisdom of that decision. Over 100,000 people turned out.’

The Inquiry moved on to ask Tate about the impact of the spycops revelations. He cited the Canadian McDonald Commission (1977-81), which had comprehensively dealt with a similar scandal there, while the American Church Committee (1976) had done a similar job with the comparable COINTELPRO affair. At the time these bodies were delivering their damning verdicts, the SDS was escalating its activity in Britain. It’s time for a reckoning.

He summed up his position:

‘The Inquiry has to decide whether it will simply protect the interests of the police and the State, even after all these years, or whether it will come down on the side of civil liberties and the right of people to have a private life free from intrusion by State security forces. I hope that the Inquiry will lead to legislation and public oversight that will limit their ability to harass those who happen to be critical of society or are fighting for social change.’

The accompanying written witness statement of Ernest Tate

For the last session of the day, the Inquiry then had one of its own staff present a summary of evidence supplied by two early SDS officers, HN218 (Barry Moss, aka ‘Barry Morris’ or ‘Barry Morse’) and HN334 (‘Margaret White’).

Officer HN 218, aka Barry Moss

(summary of evidence)

Moss was in the SDS from its formation in July 1968 until late September 1968. He returned to the SDS as a manager in 1980. His real name is Barry Moss, and while undercover he used Barry Morris or Morse. He had been a detective constable in Special Branch for only several months when he was told by Detective Chief Superintendent Arthur Cunningham that he and a dozen or so others, were joining the newly formed SDS.

He recalls:

‘I didn’t opt into it and I don’t think it occurred to anyone there that we could opt out. There was no formal training or guidance provided for the role.’

He used a cover flat merely as an address to write on attendance lists at meetings. He did not live there. He used his own vehicle registered in his own name to attend those meetings.

He believed the unit had a short term remit, gathering information about the upcoming October 1968 demonstration against the Vietnam War. In his witness statement, Moss noted the only real difference from Special Branch work was actually joining groups instead of just attending meetings.

SDS boss Conrad Dixon told him which groups to spy on, but not how to do it. However, while undercover, he had almost daily contact with his cover officer, Detective Inspector Phil Saunders.

He joined the Maoist Britain-Vietnam Solidarity Front (BVSF). He does not recall joining the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign (VSC) which was something of a rival group, but reports on the VSC include his name.

The reports mention five different groups; the Joint Committee of Communists, the Committee for Solidarity with Vietnam, the VSC’s Ad Hoc Committee, and two branches of the VSC.

MIXING WITH THE MAOISTS

He remembers people being in several of the groups at the same time and there may have been a shared Maoist ideological connection (even though the VSC had a significant ideological split with Maoists).

His reports show a mix of public and private meetings mostly concerned with planning for the October 27 demonstration, including, banner making and choosing slogans. On 24 September 1968 at a meeting of the October 27 Committee for Solidarity in Vietnam, it was recorded that a decision was made to break away from the main demonstration to target the American Embassy.

Moss confirmed at that some meetings there were SDS officers and ordinary uniformed officers not working together. At other meetings there would be more than one SDS officer, simply because their respective groups had attended the same meeting.

NINE OFFICERS VOTING

At a public meeting of the VSC’s October 27 Ad Hoc Committee, nine police officers are stated to have been present, including the majority of the SDS’s senior officers. According to the report, the significant occurrence at the meeting appears to have been a vote against the proposal made by Maoists to march to Downing Street on 26 October and then to Grosvenor Square (home to the US Embassy) on 27 October 1968. Presumably these nine officers all voted to avoid looking conspicuous.

Moss said some of the meetings raised ‘of particular interest to Special Branch’. Reports have detailed descriptions of branch members, including those with no previous trace or Special Branch record, notes of speakers expressing political opinions, and reporting of contacting journalists to arrange a private meetings.

ANTI-ANTI-APARTHEID

After he left the SDS, Moss wrote a report analysing the support of the Anti-Apartheid Movement.

Moss was the first spycop to leave the SDS, withdrawing even before the 27 October demonstration the unit had been set up to target, in order to attend an accelerated promotion course. He thinks he may have made up a family incident that required him to leave London as part of his withdrawal strategy.

Before he left, he introduced his replacement – Detective Constable Mike Tyrell HN335 – who he introduced as his “best pal” to a meeting of the Earls Court VSC. Tyrell’s cover name is unknown and he is now deceased. He is absent from the Inquiry’s list of SDS officers.

Moss said he didn’t actually see any subversive activity whilst undercover, stating:

‘The group I joined wasn’t really trying to overthrow the government, they just wanted a big demonstration’

He does recall two pieces of information that ‘were probably passed on for use in policing’ in his two months undercover; the possibility of protestors carrying ball bearings to use on police horses, and women being told to flirt with officers on the frontline to try to win them over.

Moss said that, whilst his reporting alone would not have made a great difference to policing, he does think that the October demonstration was well policed and any disorder at it was controlled as a result of the intelligence provided by the SDS as a whole.

BACK TO MANAGE

He returned to the SDS as a Detective Chief Inspector in February 1980. He was promoted to the rank of Superintendent in early 1981, and left the SDS in December of the same year. In 1995, he became commander of operations in Special Branch, with a remit that included the SDS. He became Head of Special Branch in October 1996.

[Note: Moss will be heard from again in later tranches, not least because he was a pivotal officer in the founding of the National Public Order Intelligence Unit.]

Officer HN 334 aka ‘Margaret White’

(summary of evidence)

The Inquiry has granted anonymity to the real name of HN334 ‘Margaret White’.

Prior to joining the SDS, she was a Detective Constable in Special Branch. She remembers attending the same sort of political meetings, both as an officer serving with Special Branch and with the SDS. The distinction she draws between the two roles is the need for her identity to be completely secret as an undercover officer, unlike with Special Branch where she would give her name, if asked.

Neither her memory nor the documents can say exactly when she joined and left the SDS. Whilst in the unit, she attended meetings of the Havering branch of the VSC between 30 September and 29 October 1968. She does not appear on the list of the unit’s personnel in the document entitled ‘Penetration of Extremist Groups’ dated 26 November 1968 suggesting, in accordance with her recollection, that she left the unit shortly after the 27 October demonstration.

She does not remember having any training for the role. She created her assumed background over a couple of days, altering her appearance by wearing a long haired wig, adopting a cover name and cover employment, and finding a flat where she would stay occasionally. In her witness statement, she said she knew she would be on a short term deployment that concluded with the October demonstration.

DOUBLE TROUBLE

She was deployed to Havering VSC along with fellow SDS undercover HN330 ‘Don de Frietas’. They were instructed to act as a couple, attending all of the meetings together. She describes the group as having no formal membership structure or procedure. She understood that she was to report exactly what she saw and heard. She never attended any meetings alone, nor did she author the police reports.

She was tasked to this particularly group because senior officers thought that it would be a trouble-making group. From what she saw and heard, it was not.

The Inquiry holds reports relating to the branch dated between 30 September and 29 October 1968. They record small private meetings, mainly concerned with preparations for the October demonstration, including discussions about the composition, printing and distribution of leaflets, lines to take with the press, elections for the post of secretary and treasurer and the likely maximum size of the Havering contingent (about 100 people).

Apart from them considering doing some fly posting, she gives is no evidence of any intention to break the law, or a militant attitude.

EXIT STRATEGY

In addition to information about preparations for the October demonstration, the reports record information about political activity of an individual in the Labour Party.

The final report concerning a meeting held on 29 October 1968 contains the officer’s account of the views of her group about the demonstration, that it had been ‘a complete and utter disaster’. The officer used this as an excuse to leave the group. She then withdrew from her service with the SDS and returned to Special Branch.

She only remembers infiltrating the one group during her time. Any other Special Branch reports by her were, she said, the result of specific tasking whilst a member of Special Branch and not in her SDS undercover identity.

One report authored by her in August 1968 concerned an individual and her correspondence in connection with the funding of an art college’s October 25 revolution account. Other reports from the same period have her and another SDS officer HN68 ‘Sean Lynch’, attending a private meeting of the Camden Branch of the International Socialists. The subject of the meeting was ‘Negro struggles in America’, with associated information about activism for racial equality.

Five reports in the hearing bundle relate to her work in Special Branch after leaving the SDS. They relate to groups on which the SDS did report and appear to be examples the SDS working from other sources of information such as informers on those groups, such as the Women’s Liberation Workshop and the anti-apartheid the Stop The Seventy Tour Committee.

Details of Deceased Spycops

Beyond the hearing today, the Inquiry also published documents relating to deployments of six other former SDS officers who are now deceased.

HN 68 – ‘SEAN LYNCH’, REAL NAME NOT PUBLISHED

1968-1974

Also held a managerial position in the SDS 1982-1984.

‘Lynch’ targeted the International Socialists (forerunner of the Socialist Workers Party) and Irish campaign groups, including the Irish Civil Rights Campaign, the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association and Sinn Fein. His real name is withheld by the Inquiry to protect the privacy of his widow.

HN 331 – COVER NAME UNKNOWN, REAL NAME NOT PUBLISHED

1968-1969

This officer infiltrated the Notting Hill branch of the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign. His cover name is unknown. He was killed in road traffic accident in the 1970s. His real name is withheld by the Inquiry to protect the privacy of his widow.

HN323 – HELEN CRAMPTON, COVER NAME UNKNOWN

Crampton also infiltrated the Notting Hill branch of the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign.

HN327 – DAVID FISHER, COVER NAME UNKNOWN

Fisher infiltrated the Notting Hill and Croydon branches of the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign.

HN318 – RAY WILSON, COVER NAME UNKNOWN

Wilson infiltrated various manifestations of the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign, including the north-west London Ad Hoc Committee, the Notting Hill, Croydon and Earl’s Court branches, plaus the North-West London Ad-Hoc Committee and the October 27 Ad Hoc Committee, as well as the libertarian left. Previously referred to by the Inquiry as ‘back office/ management’ rather than undercover, implying an additional later role. Author of ‘Special Branch: The History 1883-2006’.

HN335 – MIKE TYRELL, COVER NAME UNKNOWN

Tyrell infiltrated Maoist groups, plus the Earls Court branch of the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign, the October 27 Committee for Solidarity with Vietnam, the south-east London Ad Hoc Committee, the Britain-Vietnam Solidarity Front, the March 9th Committee for Solidarity with Vietnam, and the Revolutionary Socialist Students Federation.

COPS will be live-tweeting all the Inquiry hearings, and producing daily reports like this one for the blog. They will be indexed on our UCPI Public Inquiry page.

<<Previous UCPI Daily Report (11 Nov 2020)<<

>>Next UCPI Daily Report (13 Nov 2020)>>