Tranche 1, Phase 2, Day 2

22 April 2021

Opening Statements from:

Diane Langford

‘Madeleine’

Phillippa Kaufmann QC, representing Core Participants who had relationships with undercover officers

Matthew Ryder QC, representing three anti apartheid activists (Ernest Rodker, Professor Jonathan Rosenhead & Lord Peter Hain) & Celia Stubbs

The second day of Tranche 1 Phase 2 of the Undercover Policing Inquiry, being the 28th anniversary of the racist murder of Stephen Lawrence, began with the Chair, Sir John Mitting, reading out a statement from Neville & Doreen Lawrence about their son.

He spoke of the police failings, of the suspects not being charged, and that the Macpherson report from the public inquiry was a landmark in showing the police’s racist faults. But Stephen’s legacy is ultimately one of hope, reminding us change is much needed, but also possible.

There was a minute’s silence for Stephen.

Diane Langford

The first speaker today was Diane Langford, an activist in groups who were infiltrated by undercover officers in the era that the current hearings are examining (1973-82). She will also give evidence on the afternoon of Monday 26 April.

The contrast between the opening statements of yesterday’s legal representatives of the police, spycops and the establishment compared to the emotional, direct and articulate submission of Diane Langford could not be more marked.

Her statement cut to the heart of everything that is wrong with the Undercover Policing Inquiry. This summary hardly does justice to her powerful speech, which is worth reading in full, or watch on YouTube.

POOR TREATMENT BY THE INQUIRY

Diane Langford has only recently become a Core Participant at the Inquiry. In 2018, the Undercover Research Group (URG) found her story of the exposure of spycop ‘Dave Robertson’ (HN45). Later, URG discovered that the group she had set up, the Women’s Liberation Front, was infiltrated by ‘Sandra Davies’ (HN348), and had let her know.

Her name appeared unredacted in many reports of the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) disclosed at the previous Inquiry hearings last November, but it turned out the Inquiry had only reached out to her just beforehand.

‘When I was given copies they ironically came with a legal warning not to show them to anyone else.’

The Inquiry failed to ask her to give evidence, or tell her that she could seek legal representation.

By the time she knew Sandra Davies was giving evidence to the Inquiry it was too late to book a place at the limited screening venue.

Despite the poor treatment she has received from the Inquiry, Diane Langford is grateful to the Chair for, belatedly, granting her Core Participant status. She was perplexed however that, despite her 50 year history of activism, in his ruling, the Inquiry chair, Sir John Mitting, introduced her as ‘the widow of the late Abhimanyu Manchanda’ as if she was merely an appendage. Yet another example of the institutionalised sexism being present in the Inquiry as it was in the spycops.

Langford identified six undercover officers who spied on her:

Langford expressed solidarity with others targeted by spycops, especially those no longer here to tell their story and push for justice, asking:

‘how many others who were spied on are completely unaware that their names appear in these files?’

‘I’ll never know what career opportunities were denied to me, or what other barriers have been placed in front of me during my life, as a result of the machinations of the Special Demonstration Squad. I’ll never know whether unpleasant incidents – for example, being denied credit or visas, or break-ins at my home – were connected to the surveillance I was being subjected to.’

WITNESS OF INJUSTICE

As a young person Langford saw injustice in Aotearoa/New Zealand where she grew up, including racism, sexism and class discrimination. Her brothers got an education, but she left school at the age of 15. Coming to London at 22, ironically to support her brother who had won a scholarship at the Royal Academy of Music, opened her eyes. Going to movies, and reading De Beauvoir and Sartre, Barthes, Kristeva, and the Autobiography of Malcolm X after he was killed, opened the way into political activism. She was very much influenced by the events of 1968.

Talking about being part of the women’s liberation movement, Diane Langford said that, as with many others, her commitment was based on personal experience, recognised as political. She gave the example of how, when she was in her early twenties, her flatmate died of an illegal back street abortion, aged nineteen.

‘The memory of her death remains vivid for me still, at the age of 79.’

That the basic goals of the movement remain unachieved and resisted confirms their profound nature.

Langford began her involvement in the Women’s Liberation Front, which believed that patriarchal, racialised capitalism cannot, and will not, meet those goals.

She listed three dramatic events that spring to mind when recalling the period under scrutiny:

– Dave Robertson threatened my friend with violence when she outed him as an undercover.

– Banner Books was burned down by fascists while undercover officers had surveilled and had access, and I believe a man died. This needs investigating.

– Robertson ignored an allegation of attempted rape at a meeting, instead focusing on my domestic arrangements and ridiculing my partner.

WHAT IS THE POINT OF THE INQUIRY NOW?

Langford then connected the spying in the past to the new Covert Human Intelligence Sources Bill rushed through Parliament just before the November hearings in 2020, which allows police to self-authorise to commit all crime, which undermines much of the point of the spycops Inquiry.

In January 2020 the current counter-terrorism spycops unit listed peace protesters as extremists. One of them was the Palestinian Solidarity Campaign seeking to uphold international law and to promote peace, yet it is targeted as a problem to be undermined.

In Langford’s activist life, women’s liberation has always been entwined with the Palestinian struggle – there is no liberation for women under the apartheid regime in Palestine. She asked:

‘If I was under surveillance in 1970 as a member of the Palestine Solidarity Campaign, am I still under surveillance now? I became a busier activist in the 2000s, more than in the 1970s that police have admitted. Where are the files?’

INCAPABLE OF UNDERSTANDING

‘Sandra Davies’ (HN348) spied on 77 meetings, of which 55 were related to the women’s liberation movement.

‘Sounds like more than I did! Why is the women’s movement not a focus of the Inquiry? The Inquiry is colluding with the state to limit the search for evidence…

‘To read these reports is to see some of the greatest ideas of our time crushed into the narrow confines of a mentality absolutely lacking in the capacity to comprehend them…

‘We see the callous use of women’s bodies by misogynous male officers who see such abuse as a perk of the job, and, a confluence of the sexist behaviour and patriarchal attitudes of so-called left wing men in socialist groups and that of those spying on them.’

THE REFUGE OF POOR MEMORY

‘This Inquiry reiterates the intrusive processes of surveillance, requiring the victims of spying to explain and justify themselves, when it is the perpetrators of surveillance who should be interrogated and held accountable.

‘Remarkably we witnesses are again being subjected to intrusion into our personal and political lives, as if some retroactive justification could be thereby found for utterly dishonourable and indefensible police actions, whereas the perpetrators of abuse are granted impunity, anonymity or the refuge of poor memory.’

The SDS reports of the 1970s show sexist and racist ideas were endemic.

This was illustrated time and again by HN45 and HN348. For example, a report from August 1, 1972:

‘so-and-so is a member of the Revolutionary Women’s Union. She lives in a council flat at ADDRESS GIVEN with her two children aged 6-and-a-half years and three years and her mother so-and-so. She is a divorced woman and is in receipt of £8.50 per week Social Security. She attends Revolutionary Women’s Union meetings regularly and is particularly interested in agitating for 24-hour nurseries. This woman is on very friendly terms with so-and-so. Her description is: Aged about 23 years, very thin build, medium length fair hair, blue eyes, very pale complexion, poorly clothed but neat and tidy, wears black rimmed glasses, cockney accent.’

The internationally celebrated artist David Medalla, who passed away in January, is described by HN348 like this:

‘Asian features and colouring, dirty appearance, very poorly clad. He is very opposed to the current Government in the Philippines.’

That government was the notorious Marcos dictatorship – just to provide historical context.

Browsing the disclosure provided by the Inquiry, Langford found other disgusting examples of racism and sexism: On 1 June 1978, a report about the Federation of London Anarchist Groups informs the Special Branch that a subject had cut his beard off ‘to reveal that he has a long face, large Jewish nose and full lips.’

A report signed off by Angus McIntosh, about the Women’s Organiser of the International Socialists, dated 22 October 1976, states she has :

‘typically Jewish lilt to her … and rather prominent nose, always scruffily dressed in blue jeans and T-shirt (without a bra).’

‘A negress was in the audience’ according to a July 1976 report of a meeting of Hackney International Socialists that discussed self-defence strategies for victims of physical attacks by the National Front.

What did 1970s undercover officers do to stop the National Front attacking people of colour? They were spying on anti-fascists.

‘These patronising violations of people’s personal space, of suppressing a child’s right to demonstrate against state-sanctioned physical abuse, the racist, anti-Semitic, sexist and judgemental descriptions of people’s personal appearance that filled the notebooks of the secret police may not amount to much in the eyes of the Inquiry. It’s the accretion of them that are the stuff of authoritarian regimes, hence the expression “petty apartheid”.’

ABHIMANYU MANCHANDA

Diane Langford was also very critical of the portrayal of her late former partner, Abhimanyu Manchanda (‘Manu’):

‘HN45 displays a vindictive hatred of Manu and a peculiar obsession with our personal relationship and child-care arrangements. He sent detailed reports to the Special Branch about what he apparently saw as transgressive behaviour – a man looking after his own child – and expressing horror that I was “sent out to work.” He informs his superiors of Manu’s “insufferable anecdotes” about our baby.’

In her Witness Statement, she dealt with the Inquiry’s inappropriate Rule 9 written questions about my personal relationship with Manu – in fact repeating this behaviour.

There is nothing in the reports about them overthrowing the state. Nevertheless, HN45 portrayed Manu as a danger, saying he only went on demos to cause violence. Which is rubbish, he knew you can’t tackle the state head on.

Why is Manu referred to in reports by his surname while others get their full names? That too smacks of imperialism.

FROM NAPALM TO BUNNY GIRLS

‘What did the Inquiry have in mind when they asked me about Dow Chemicals? Is the implication that Dow Chemicals, whose inhuman war crimes have never been accounted for, was under the protection of the British State? It may help the Inquiry to know that Dow Chemicals was the manufacturer of Napalm, a firebomb fuel/gel mixture used by the American military against Vietnamese civilians…

‘The continuum I spoke of earlier, can be perceived in UK state protection being accorded to Israeli arms manufacturers, in particular Elbit, who boast that their equipment is “battle tested” on Palestinians, despite widespread public disgust at the brutal treatment meted out to Palestinian civilians.’

What was behind the Inquiry’s question about picketing the Playboy Club? Does the Inquiry regard The Playboy Club, whose employees are referred to as ‘Bunny Girls,’ as an institution worthy of special protection by the secret police?

HN348 referred to the 1970 Miss World protest as an event that was organised by the Women’s Liberation Front, prior to her deployment. They actually didn’t organise it, but Langford did attended the demonstration.

‘It was a magnificent disruption of an exploitative commercial event degrading to women. It was not a threat to public order or security.’

THERE’S NEVER JUST ONE COCKROACH

Inquiries since the Macpherson Inquiry into the death of Stephen Lawrence have been devalued by the manner in which they’ve determinedly obstructed genuine ‘inquiry.’

For example, Priti Patel set up an inquiry into the atrocious police violence against women at Clapham Common, an incident that she herself set in train.

‘While the Inquiry is heavily weighted in favour of the State, how are we going to find out when the abuse started? I hope the Inquiry will not be deflected by the myth of “a few rotten apples.”

‘The cynical attitudes of the UCOs as evidenced by their misogynist reporting in the past and current lack of remorse makes it inevitable that any opportunity to take advantage of women would have been taken. There’s never just one cockroach.’

‘Where are these files kept? Who has access to them? Dozens of people, whose names recur in the files I’ve had sight of, have absolutely no idea that the secret police came into their homes under false pretences and spied on them. At the bare minimum anyone whose private space was violated, resulting in them being named in these files, should be informed and invited to be part of the inquiry.’

We need to see the faces of undercover officers, if only to stop suspecting our innocent old comrades of being cops. Why are the officers not compelled to supply contemporaneous photos themselves?

A request for a contemporaneous photograph of HN348 was declined by the Inquiry as they were not holding one in their files. Why not ask HN348 to supply one, as Langford’s legal representative suggested?

‘it bears out the idea that, as Audre Lorde put it, “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house”. It is clear that women, People of Colour and others working for a better world will need to continue with our grassroots campaigning on behalf of ourselves and one another.

‘However, my hope is that this Inquiry will, in fact, prove useful to us in such struggles for justice, human rights and freedom.’

For more, see Diana Langford’s blog and her political memoirs

Full opening statement from Diane Langford

‘Madeleine’

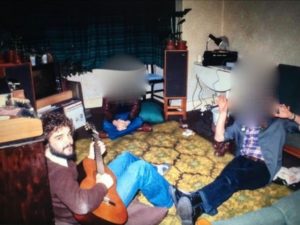

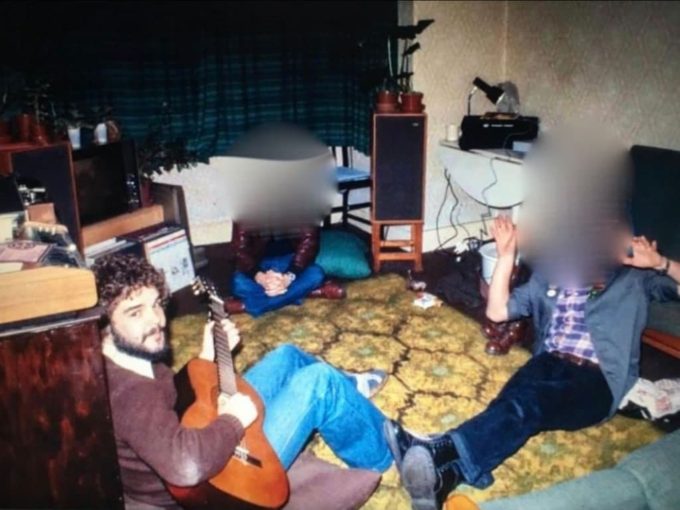

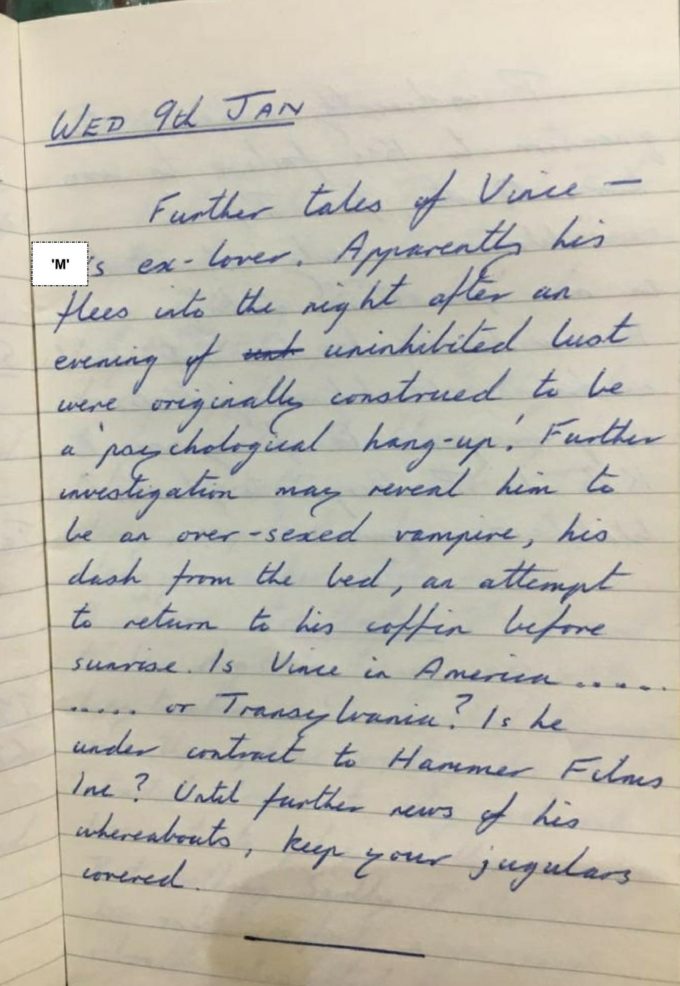

‘Madeleine’ was deceived into a relationship by ‘Vince Miller‘ (HN354) towards the end of his infiltration of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) while undercover from 1976 to 1979.

She had known him for three years by the time the relationship began. The relationship lasted for a short period of time over the summer and early autumn of 1979 until he suddenly disappeared.

Miller has admitted to a total of four sexual relationships during his deployment but insists they were all one-night stands. Despite him admitting that, the Inquiry had previously referred to his deployment as ‘unremarkable’ and granted him anonymity.

Madeleine not only describes a relationship lasting several months, as verified by her diaries, she also emphatically condemns Miller’s account of how they initiated their relationship.

‘the implications of some of the disclosures made by Vince Miller are also deeply offensive and revelatory. Describing the night we first got together he has stated that I “unexpectedly invited him to my bedroom” after we had both been drinking.

‘What exactly is he trying to say? That I was drunk and looking for a random man to have sex with? This is a deliberately untrue misrepresentation of the events of that evening.’

Since Madeleine has come forward to challenge such claims, Mitting has now agreed to release Miller’s real name to Madeleine. But she asserted:

‘HN354 shouldn’t have had his identity protected in the first place. HN354 lost the right to privacy due to his abusive acts and no legitimate reasons have been given for withholding his real name’.

POLITICAL ORIGINS

Madeleine described how her politics stemmed from her family background. She grew up in a large poor working-class family. Her father was a lifelong socialist and an active trade unionist, and both her parents were anti-racists.

Her father was part of the anti-fascist protests at Olympia in 1934 and at Cable Street in 1936 where he joined thousands of East Enders who fought to stop Oswald Mosley and the British Union of Fascists marching into a largely Jewish area to intimidate and attack the community.

Madeleine’s dad went on to join the International Brigades fighting fascists in the Spanish Civil War. He was at Guernica when the Nazis destroyed the city. He came back to the UK and volunteered to join the British Army at the start of the Second World War to continue his fight against fascism.

Madeleine wonders whether her father, a double war hero, would also have been considered a ‘subversive’ and a ‘dangerous extremist’.

The spycops reports just released by the UCPI and branding political activists as ‘subversives’, ‘dangerous extremists’, and ‘troublemakers’ paint a picture of people unrecognisable to Madeleine’s experience as an activist. To find out that the words were written by Miller, someone she trusted and cared about, is doubly painful.

She described the bigger picture, with the stilll-unfolding spycops scandal needing ‘to be understood and framed as the logical expression of the actions of a state and security apparatus wedded to the interests of the ruling class.’

TEENAGE ACTIVISM

Madeleine moved on to her youthful activism with the Socialist Workers Party. She recalled organising branch and public meetings, and endless discussion and debate. The SWP was open and welcoming, and had nothing to hide. It was public, selling the weekly Socialist Worker newspaper and leafleting on the High Street, on housing estates, pickets and demonstrations.

Madeleine said that Miller embedded himself deeply into the life of the SWP branch for three years. He described the branch as a ‘social and inclusive bunch’ – a fact that which he took full advantage of. He became treasurer (which seems to have been a common role for spycops taking office in groups), and was also on the social committee and in the industrial group.

She has found out that:

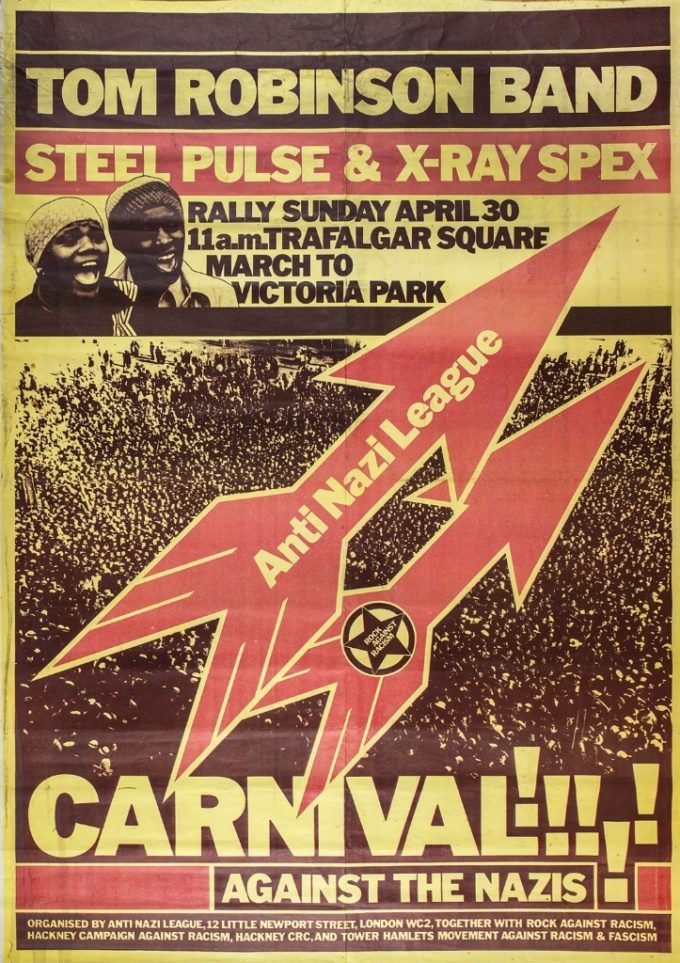

‘17 spycops were embedded in our party and yet in truth, the biggest threat to democracy in the UK at this time was not from the left but from the reinvigoration of fascism which once more began to emerge from the shadows and reveal its ugly face.’

THE GROWING THREAT OF FASCISM IN THE 1970S

Madeleine spoke about the political and economic backdrop in the UK during this period, which would prove a fertile breeding ground for fascism. Fascists attacked the left with increasing violence, attacking paper sellers, and committing arson against bookshops. In May 1978 a young Asian man, Altab Ali, was stabbed to death in Whitechapel. So where was the monitoring of the far-right by our security services?

The area around The Bladebone pub at the top of Brick Lane in London’s East End was a well-known haunt of the National Front (NF). After repeated attacks on the diverse community, protection was organised and the SWP were part of it. Miller describes the area as ‘heavily policed’ but Madeleine says she only saw that happen when there was active left wing presence. The protection that the community received was from activists like herself, not the police. Miller depicted the confrontations as a mere territorial dispute between the Swp and NF.

Miller’s analysis in his witness statement, describing the SWP and the NF as similar is very telling. Madeleine mentioned that a police report on a speech given by fascist John Tyndall at the NF ‘Battle of Lewisham’ march, describing him speaking in his ‘usual forceful manner’, but his exhortations to violence went unrecorded by spycops.

Madeleine gave another more personal example of police bias towards the far right:

‘I recall one Saturday selling papers at Barking Station in the week following a violent sledgehammer attack on a young female SWP member by a fascist who broke her pelvis. Jeering NF members watched as a tall man who had previously approached us in a friendly manner to buy a paper came up behind me and snatched my papers calling me a ‘red bitch’ and telling me to go away. He then walked over to the police who had witnessed his act and proceeded to laugh and joke with them. When I asked the police if they had seen what he’d done they smirked and told me to go home’

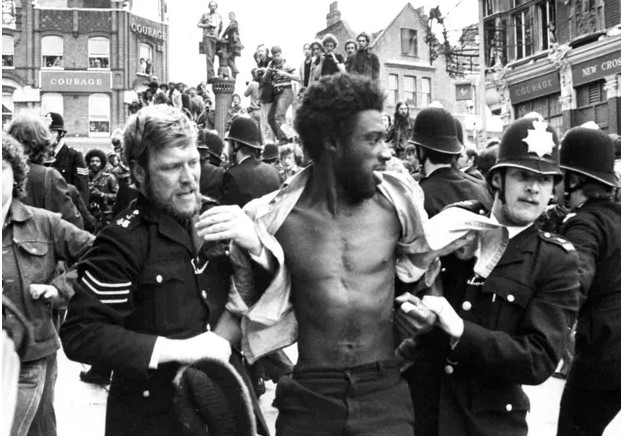

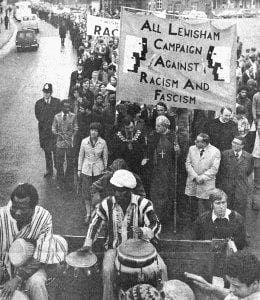

THE BATTLE OF LEWISHAM

On 13 August 1977, 500 NF supporters planned to march from New Cross to Lewisham. There was a huge mobilisation against it. At an anti-racist rally beforehand, a crowd of thousands was addressed by those notorious subversives the Mayor of Lewisham and the Bishop of Southwark.

Police tired to guide the NF marchers but thousands of people blocked them, and there were extended disturbances on the streets. It quickly became known as the Battle of Lewisham.

Madeleine emphatically refutes a claim made by Miller – and repeated in the SDS Annual Report that year – that bricks were stockpiled at various locations by the SWP along the planned NF route and that members of the SWP carried weapons to the march in bags.

‘I was at the demo on the day and can state categorically that no one that I knew had weapons or would have done such a thing. It is an easy assertion for HN354 to make – where is his evidence? Where are the names? Or should this be seen as an attempt to blacken the name of the SWP?’

The police were in reality undermining the efforts to fight fascism and combat racism by the only forces mobilising to protect communities and defeat those evils.

Madeleine continued:

‘The Battle of Lewisham is now rightly considered a watershed moment like Cable Street in the fight against fascism in this country. Unable to control the streets, the NF went into decline and the event is now proudly remembered as the moment when the far right was again defeated. It is now commemorated by the local council and seen as a symbol of a community coming together to say yes to black and white unity and no to the forces of hate.’

A KNOCK AT THE DOOR

All that was over 40 years ago.

Early one Saturday morning at the end of February 2020 Madeleine received an unexpected visit. Like anyone door-stepped early on a Saturday morning by someone with a hand-delivered an official-looking letter, she felt a wave of anxiety and stress.

‘What was I about to be told? Was I about to be given some terrible and tragic news?’

It was a solicitor from the Undercover Policing Inquiry. Madeleine received the news that ‘Vince Miller’ was not a boyfriend and comrade.

She couldn’t think of the man she’d known as a devious abuser. She remembered him as someone who seemed emotionally vulnerable – as she was herself at the time, having just left an abusive partner. This targeting and use of trauma as a means of getting close to surveillance targets is emerging as one of the most common themes within SDS deployments.

‘I now know that the Vince Miller I thought I knew doesn’t actually exist. He is a wholly constructed fiction, a fake identity used as a tool for the purposes of political surveillance sanctioned by the state which infiltrated the most intimate parts of my body and my life…

‘The initial revelation of the true identity of a man with whom I had enjoyed an intimate sexual relationship and shared thoughts and feelings of a deeply private nature left me feeling nauseous and revolted. I felt degraded and abused and continue to feel a real sense of violation. I feel that both my trust and my values have been betrayed by an agent of the state.’

THE TRUTH IS SECRET

Madeleine was told that there were a substantial number of intelligence reports on her and her friends which she could only see if she signed a secrecy agreement not to even discuss the contents with anyone else apart from her lawyer.

‘The knowledge that the state holds secret files on me filled me with anxiety and a sense of paranoia. I wanted to know. What is in those files? What information is held? What details of a personal nature do they contain? And how personal and intrusive are those details?’

For Madeleine, not being able to share this with her husband was especially hard. It cuts off a source of support for both of them as they deal with the impact of the truth.

All the Inquiry’s core participants have been in this position, not being able to share it or discuss it with anyone – even others who’ve been given the same documents.

She condemned the cruelty of the police and Inquiry refusing to hand over documents until just before the Inquiry hearings will discuss them. There are women who have known their partner was a spycop for many years, and who are not due to receive the reports on them for many more years.

Later, at the end of Madeleine’s testimony, Mitting said that he would ask the Inquiry lawyers to see that her husband could see the documents. This is too little too late.

When another core participant had earlier asked whether she could share her disclosure with one other trusted person it was refused. Not being able to discuss these matters with anyone else other than your legal representative adds another layer of trauma and stress for those affected by the actions of the state.

‘The files that I have seen contain information of a very intrusive and personal nature. They reveal detailed physical descriptions of myself and my flatmates and information about my employment, my wages, my address, and the precise time, date, and registry office location of my first marriage which happened before Miller’s deployment but appears in a report written by him.’

CRADLE TO GRAVE SURVEILLANCE?

‘I have also discovered, to my horror, that MI5 has had files on me since 1970 when I was aged 16 more than 6 years before HN354s deployment. This is shameful. Most people would consider a 16-year-old little more than a child and the Inquiry now knows that other children have been spied on too. I was incredibly young when I first became politically active in left-wing groups. We know the SDS was formed in 1968 and that extensive spying was happening at that time. I therefore wonder if I was spied on as early as 13 when I was a schoolgirl?

‘Miller has even reported on the pregnancy of a woman in our branch and the name her baby was to be given. This went straight to MI5. Was this unborn baby given a security service’s file? Was my child given a registry file too? I find it outrageous and deeply offensive to realise that we have been treated as “targets” regarded as “subversive and dangerous extremists” and that relationships have been used as a tool for state surveillance via the invasion of our lives and bodies.’

WHAT’S CHANGED?

Madeleine questions how much has changed in police culture. Did Miller contribute to the prevailing culture within the Metropolitan Police at that time and since, as he later became a senior officer?

She asked for all reports on her to be removed from the archives and destroyed. The SDS has shown us that secret policing, by its unscrutinised nature, is liable to abuse citizens. There is no telling how the information on file may be used against its subjects in future.

We’ve already seen Miller downplay the harm he did to others, and he is far from alone among the spycops in this regard. Madeleine said spycops should be given no leeway for their behaviour because any allowances made to them because of their position or role in society will be exploited by them in order to cover themselves.

As well as today’s opening statement, Madeleine will giving evidence to the Inquiry on Monday 10th May.

Full opening statement from ‘Madeleine’.

Phillippa Kaufmann QC

representing Core Participants who had relationships with undercover officers

Phillippa Kaufmann QC

Kaufmann began by saying it is now clear that in the era being examined by the current UCPI hearings, 1973-82, numerous spycops had sexual relationships with women while using their undercover identities.

Some of these women were the targets of their spying operations, others came into contact with the spycops socially.

We were told in the past that these deceitful relationships only rarely occurred, but the evidence now being published provides a different picture.

It has now been confirmed that at least eight officers entered into such relationships over a five year period. Of these, ‘Jim Pickford‘ (HN300, 1974-76) and perhaps ‘Alan Bond‘ (HN67, 1981-86) had children with women they’d spied on.

The practices and culture established in this period led to what came later. It shows the long running sexism which infected the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS).

WHY WEREN’T WE TOLD?

It’s not just the SDS that’s at fault. The Inquiry only contacted Madeleine in February 2020, and got a lawyer late in the year, yet she was known about when the Inquiry first dealt with the spycop who abused her, ‘Vince Miller‘ (HN354, 1976-79), in 2017.

Why wasn’t she contacted earlier? Why were we assured a woman would be sent to tell her the awful truth, but instead a man went to her home?

Why wasn’t Madeleine put in touch with Police Spies Out of Lives – which represents and supports women deceived into relationships by spycops – as the Inquiry had promised?

In 2017, Miller gave the Inquiry the name of the other Socialist Workers Party member he had sex with. Why did the Inquiry also wait three years before starting to try to to find her?

The Inquiry accepted his version at face value, called his deployment ‘unremarkable’, and ruled that his real name would not be published because he deserved privacy.

The order to protect his name will now be revoked. Why has this changed, apart from the fact that Madeleine is now actively involved in the Inquiry? Why should that make the difference, given his acts remain unchanged? Why was he ever seen as deserving of anonymity?

NOT JUST ACTIVISTS

Miller also admitted to having sex with two other women (who he says he wasn’t sent to spy on) during his deployment. Why didn’t the Inquiry tell us about that straight away?

Those other two women were also deceived by a paid State character who was the opposite of what he claimed to be. This isn’t a private matter for the officer, it’s as relevant to the Inquiry and the public as a relationship with an activist. We have no idea how many other spycops the Inquiry knows about who have also already admitted they had sex with non-activist women while undercover.

The Inquiry must already be well aware that spycops are liable to lie about this subject. Jim Boyling told the Met that Rosa, with whom he ended up having two children, had nothing to do with his target group. It was a bare-faced complete lie. Any instance of a spycop using their identity to deceive women into sex is an abuse of power and a violation of the women. It always needs investigating.

The Counsel to the Inquiry told us yesterday they won’t investigate every relationship, which is one thing. But why isn’t it telling us about ones they know about, and whether it is trying to find the women involved?

Trust is a major issue for these deceived women. The lack of transparency from the inquiry generates gratuitous anxiety, distrust and fear.

Any spycop who deceives someone into sex forfeits their right to anonymity. It was not necessary to their deployment. This practice was gratuitous and a grossly intrusive invasion of private citizens’ lives.

HN21 also admitted, in 2019, that he had sex with 2 women while undercover, yet still has anonymity for both his real and cover names. Why?

SPYCOPS SEXUAL RELATIONSHIPS 1973-82

In the era 1973-82, which the Inquiry is currently examining, eight officers are known to have deceived women into sexual relationships.

HN302 (cover name restricted, 1970s), whose deployment began in 1973,admits one sexual encounter with a woman from another group rather than the one he spied on. He said ‘circumstances presented themselves’. He says it wasn’t necessary to his deployment and he didn’t think it important.

Richard Clark (‘Rick Gibson’ HN297, 1974-76) had relationships with ‘Mary‘ and her flatmate in 1975, and two women in Big Flame. He told his cover officer that this had caused his cover to be compromised, which implies that he told these women different stories and they realised.

Big Flame found the birth and death certificates of the child whose identity he’d stolen. Mary and Richard Chessum’s statement to the Inquiry on Friday will give more detail.

‘Jim Pickford‘ (HN300, 1974-76) fell in love and wanted to tell the woman the truth about himself. Another officer helped him tell the SDS managers. His wife found out and their marriage ended. He married the new woman and had a child with her, though that marriage didn’t last and she can’t be found today.

HN21 (cover name restricted, late 1970s-early 1980s) admits to occasional sexual encounters with women he knew from ‘an evening class’ (we don’t know what kind of class that was).

‘Barry Tompkins‘ (HN106, 1979-83) is mentioned in a security liaison note as having a relationship, though he denies it. The Inquiry hasn’t called him to give evidence, so we may never find out more about this.

‘Vince Miller‘ (HN354, 1976-79) deceived Madeleine and three other women into relationships. He’s blamed it on having been drunk every time. He lied to the Inquiry about it. He is adamant that his sexual relationship with Madeleine was a one-off event, but she is very clear that they had an ongoing relationship, for months. She still has a diary showing the dates they spent together, but it is notable that he never stayed overnight.

‘Phil Cooper‘ (HN155, 1979-83) told the Inquiry’s risk assessors he had several relationships, but now denies having said it. The officials he spoke to will be giving evidence.

‘Alan Bond‘ (HN67, 1981-86) lived with Vince Miller before Miller was deployed. He may have had a child while undercover. Despite this, he was promoted, and went on to be second in command of the SDS in the 1990s. This means that he oversaw many of the officers who we know also deceived women into relationships, including John Dines, Matt Rayner, Bobby Lewis and Andy Coles. His attitude to this issue must be explored.

‘Paul Gray’ (HN126, 1977-82) was alleged to have had an affair with a fellow officer, in a letter received by his managers that is thought to be from his wife. His managers found allegations ‘were not totally accurate’. Does that mean the affair was with someone he was spying on, rather than a colleague? None of this is actually mentioned in HN126’s witness statement.

We now know that during those five years, a third of the officers in the unit engaged in sexual relationships while undercover. There may be more. But the Inquiry is only calling one, Vince Miller, for evidence.

The issue of sexual relationships is one of the main reasons for the inquiry’s existence and must be prioritised. At the November hearings, we were provided with extracts from each individual officer’s witness statement (with their cipher number attached).

However, it appears that this time, the Inquiry intends to only supply a short ‘gist’, blending the officers’ accounts together, rather than directly quoting any extracts, or identifying which officers are addressing which points. This makes it impossible to ask any meaningful questions of these officers, and makes the gist almost worthless. There’s no good reason why the inquiry cannot provide individually identifiable extracts like last time.

When these spycops give evidence in secret ‘closed hearings’ we will be demanding that as much of this evidence as possible is published afterwards and only the minimum details necessary are kept confidential..

NOT JUST ACTIVISTS

Sexism was endemic in the SDS – reports rate women’s attractiveness and comment on the size of breasts. No account was taken of the impact of the officers’ behaviour on their wives and families. When Paul Gray’s wife alleged an affair the managers’ only concern was protecting the unit’s secrecy; there was no concern for her welfare.

‘Sandra Davies’ (HN348, 1971-73) the first female SDS officer, had her welfare totally disregarded. She was just a tool, used to spy on women’s groups that were closed to men.

Spycops gave no thought to the dignity of women, to their right to choose who they had sex with, the risk of harm if they found out the truth, or what would happen if they got pregnant. Most officers involved readily admit there was no necessity for these relationships.

Numerous women’s organisations were spied on, despite posing no threat at all to public order. It was just a deep hostility to women’s equality.

With at least a third of officers having sex with women while undercover, management cannot claim ignorance. By 1971 they knew deployments were going to be long, about four years. It was clear spycops were becoming important activists and socialising. Deploying married officers clearly didn’t prevent them deceiving women into sexual relationships.

‘Graham Coates’ (HN304, 1976-79) reports officers making joke references to sexual relationships in front of managers, who were ‘deliberately blind’. Jim Pickford and Rick Gibson had reputations for chasing women.

Why would Coates be lying? We’ve confirmed the officers Coates names did in fact have such relationships. His account is clearly credible. If he is telling the truth, the other ‘amnesiac’ officers must be lying.

QUESTIONS FOR BOSSES

It appears Rick Gibson may have deliberately targeted women in order to reach an influential position in the group he was infiltrating. This is hugely significant for the management.

The SDS’ 1974 annual report say security is top priority, and the frequent meetings of all spycops keep close tabs on what officers are doing and feeling. Later reports reiterate that there is constant contact with supervisors and very close monitoring of every spycop.

There’s no question that supervisors would have listened carefully to what spycops reported. Officers must be hiding the truth from the Inquiry. We can’t take their word at face value.

We know Pickford and Gibson’s relationships were disclosed to managers, and that they suspected Tompkins of having one. They absolutely knew that this went on, and they did nothing. The message to the spycops was therefore that there’s nothing wrong with the practice Doing nothing to safeguard the women is the result of the police’s institutional sexism.

From the early days, the SDS had a culture of spycops using the bodies of women as a perk of their jobs. A state institution that exists to serve the public they’re abusive. It is deeply misogynistic. And it appears to have become part of the armoury of tactics.

If Alan Bond fathered a child while undercover, this has major implications. But he won’t give evidence to the Inquiry due to ill health. The Inquiry has known of his condition for three years yet has not taken a statement from him.

After all this misogyny in the 1970s, a 1981 Special Branch memo refers to an early spycop named Miss Pelling, who infiltrated the Communist Party of Great Britain in 1921. She remembers colleagues as gentlemen who never took liberties.

The memo says:

‘This, naturally, is as true of the present Branch’s treatment of the fairer sex as it was in Miss Pelling’s day’

WE NEED EACH OTHER’S KNOWLEDGE

The Inquiry needs the help of those who were spied on. They must not just be contacted but given full disclosure of documents relevant to them with plenty of time to read and respond so they can expose the lies.

‘Alison‘, deceived into a relationship by spycop Mark Jenner in the 1990s, has highlighted lies in the reports about her. Jenner’s reports don’t identify her even when she was at events. He appears to have deliberately written both himself and her out of reports. But Alison can shed light and show the lies, and the real impact Jenner had.

There are so many Alisons who could do the same for this phase of the Inquiry but who won’t get a chance to, because the Inquiry is keeping the facts secret.

Spycop Mark Kennedy told the Home Affairs Select Committee that the ‘two’ women he had sex with (real number: at least 11) ‘provided no intelligence at all’.

Yet at this moment, one of those women, Kate Wilson, is at the Investigatory Powers Tribunal abundantly proving she was a main target of Kennedy’s deployment.

Spycops lie, the women they abused can prove this and help to uncover the truth.

The new extra delays to the Inquiry are simply cruel to the people waiting for answers. Women deceived into relationships by spycops should be given their files, and any documents that mention them immediately. The Met have said they’re happy to do this, if the Inquiry decrees it.

The Inquiry Chair, Sir John Mitting, responded that delays are inevitable, and that ‘perhaps the request cannot be fulfilled’. He gave no reason at all as to why this might be.

Full opening statement from Category H Core Participants (Individuals in Relationships with Undercover Officers)

Matthew Ryder QC

representing three anti-apartheid activists (Ernest Rodker, Professor Jonathan Rosenhead & Lord Peter Hain), & Celia Stubbs

Matthew Ryder QC

Finally today, an opening statement from Matthew Ryder QC. He represents anti-apartheid activists Ernest Rodker, Professor Jonathan Rosenhead and Lord Peter Hain, as well as Blair Peach’s partner Celia Stubbs.

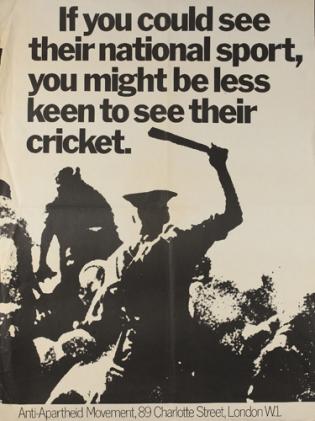

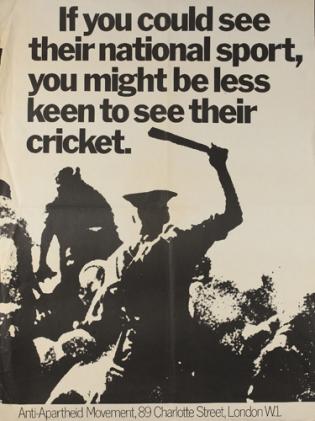

From the 1960s there was a large, global, anti-apartheid movement. They were right, and their opponents were wrong. The British government appeased and supported a regime it should have opposed.

Ryder stated that It should be a matter of deep regret that spycops targeted anti-apartheid campaigners. The real threat to democracy was the apartheid regime itself.

The Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM) was formed in 1959 and was not affiliated with any political party. Peter Hain was part of the ‘Stop The Seventy Tour’ (STST) which campaigned against tours by South African sporting teams.

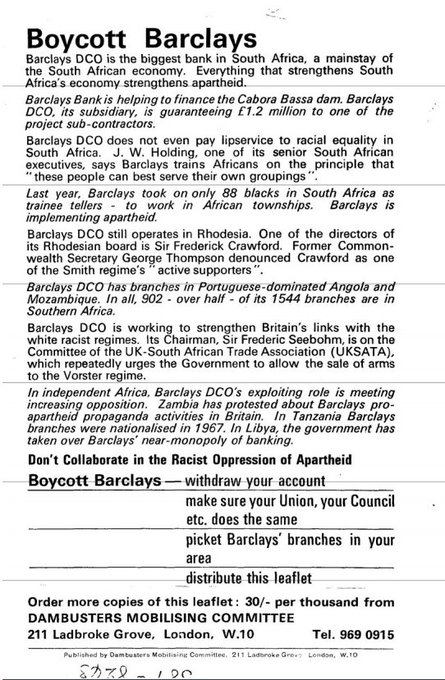

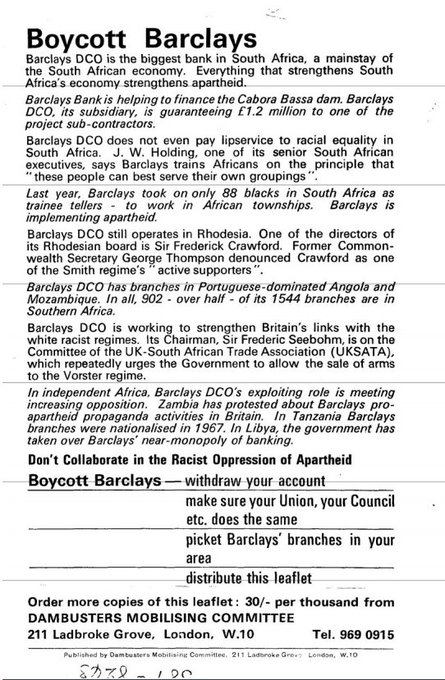

Dambusters Mobilising Committee leaflet

The Dambusters Mobilising Committee opposed the sanctions-busting Cahora Bassa Dam project in Mozambique, which would directly benefit South Africa’s apartheid system. DMC was also targeted by spycops.

The spycops were partisan; they spied on anti-apartheid groups well into the 1970s, long after the Stop The Seventy Tour, while ignoring the growth of far-right groups. The right-wing intimidation and violence suffered by anti-apartheid groups were seen as regrettable but understandable by the spycops. Those promoting racial equality were seen as the problem, rather than the racists.

The bias was so pronounced that the first spycops infiltration of the far-right National Front came about by accident when an officer infiltrating the Workers Revolutionary Party was asked by his unwitting targets to spy on the NF!

Spycops suffered from ‘mission creep’, spying on not just the ‘ultra-left’ but anyone on the broad left, irrespective of whether they had anything to do with disorder. Spying on any group could be excused as a stepping-stone to a group that was more of interest to the police. This was apparent in the deployment of Doug Edwards (HN326, 1968-70)who infiltrated the (law-abiding) Independent Labour Party.

MURDER IN LONDON

The South African State’s security service was active in London in the 1970s, targeting the African National Congress and Anti-Apartheid Movement. Peter Hain had a letter bomb delivered in 1972, opened by his 14-year-old sister. The incident remains uninvestigated.

Bombings and murders were committed against anti-apartheid campaigners. Military materials were used. Few charges were ever brought. Some of these attacks were later admitted to by South African agents.

The spycops seem to have been wholly uninterested in pro-apartheid violence. Instead, they obsessively collected information on a wide range of left-wing groups who opposed it.

The police lawyers told us yesterday that we needed historical context to understand the spycops. Well, here it is.

Yesterday the police told the Inquiry said they would have behaved identically if a racist campaign had opposed a black sports team touring England. But supporting racism is different from opposing it. Equivocation between the motivations and actions of the left and far-right was apparent in the witness testimony of Madeleine earlier.

Yesterday the police told the Inquiry said they would have behaved identically if a racist campaign had opposed a black sports team touring England. But supporting racism is different from opposing it. Equivocation between the motivations and actions of the left and far-right was apparent in the witness testimony of Madeleine earlier.

This sounds a lot like the police 23 years ago, telling the Macpherson Inquiry into the murder of Stephen Lawrence that it had a colour-blind approach. It is as if they have learned nothing.

It is also a lie, given that there were active violent racist campaigners at the time and the undercovers left them alone. That now, today, they cannot see why this is wrong is highly regrettable.

The SDS officers recorded extraordinary and gross levels of detail. The birth of Ernest Rodker’s son and a note saying that Ernest himself had been admitted to hospital were reported and copied to MI5, as were reports about who was at Peter Hain’s family home including his younger siblings.

This is what a totalitarian regime would do with dissidents. Parents are now having the chilling experience of reading secret police reports on their children.

A 1975 report on Ernest Rodker names elected councillors and their choice of reading material. It was also copied to MI5. The Labour Party conference was reported on by spycops. Peter Hain asks if the Liberal and Conservative conferences were ever spied upon?

If, as is plausible, this information was passed by MI5 to their South African counterparts, it is the very opposite of protecting the public.

The Stop The Seventy Tour was not ‘subversive’. SDS officer Mike Ferguson (HN135) had a key organisational role in the group. He then went on to hold senior positions in the spycops unit, recruiting and advising new officers. It seems his work was perversely viewed as a good example.

WRONGFUL CONVICTIONS

The excuses for targeting anti-apartheid groups need debunking. Contrary to the police version, violence was never an aim or method. Contemporaneous documentation proves it. It was not secret or revolutionary, it simply opposed the cruel and racist South African regime. Mike Ferguson’s reports do not suggest any violence at any time. Officer Dick Epps says at one demo people were told to attack police. This was emphatically denied as a lie by all of the activists involved.

The arrest and prosecution of spycops officer ‘Michael Scott‘ (HN298, 1971-76) at the ‘Star and Garter demonstration’ is a powerful example of how spycops deliberately abused their power and eroded the judicial process.

On 12 May 1972, in the car park of the Star and Garter Pub in Richmond, activists blockaded a coach of rugby players on their way to the airport, about to embark on a tour of South Africa. One of those arrested and convicted was undercover officer ‘Mike Scott’.

As mentioned in yesterday’s hearing, Scott was using the stolen identity of a man who was still alive. Scott spied on privileged legal conversations between lawyers and defendants. He did not correct the police ‘s claim in court that the protesters were on the road, when in fact they were on private land: the car park. Senior officers endorsed his going to court to lie about this.

This is an early example of spycops creating miscarriages of justice.

Home Office guidance in 1969 is unequivocal – undercover agents should avoid misleading courts at all costs. The spycops unit simply ignored this .The SDS tradecraft manual of the 1990s specifically told spycops that they could disregard the usual rules about not lying to courts.

If we conservatively estimate that there was one wrongful conviction per officer per year of service, it means the spycops caused about 600 wrongful convictions. It is a huge scandal that is going relatively unremarked upon.

Another example was the prosecution of ‘Desmond/Barry Loader‘ (HN13, 1975-78) in 1977. He and others were tried for public order offences. Barry’s charges were dismissed while the others were convicted of public order offences. He was arrested again shortly after this, leading to a conviction. However he was only given a small fine and ‘bound over’. Neither the defence nor prosecution was told that he was an undercover officer. It appears that the only disclosure was to ‘a court official’ (name redacted so we have no idea who this was) who fixed the results.

The 2015 Ellison Review of Potential Miscarriages of Justice said that spycops must have withheld evidence from court, including evidence that would have exonerated the defendants.

In 1974, infiltrating the Troops Out Movement, spycop Mike Scott was accused of being a spycop officer by Gerry Lawless. Some spycops chose to accuse genuine activists of being spies to distract attention from themselves. Scott, however,chose a different tactic – of punching Lawless in the face, so hard that he broke a finger. These officers considered themselves to be above the law in many ways.

Mike Ferguson, who infiltrated the Anti-Apartheid Movement, is – uniquely – known by his real name, but his cover name is restricted. This means those he spied on cannot know he was a spy and cannot come forward. This has led to another Mike, a real campaigner called Mike Craft, being accused of being the spycop. Craft’s comrades here emphasise that he was wholly innocent. This is also a reminder to all activists to never accuse comrades of being a police spy without any hard evidence.

Even by the standards of the day, the SDS’ targeting anti-apartheid campaigners was an unjustified, disproportionate, and erroneous political choice. The Inquiry should confirm that as a matter of historical record.

CELIA STUBBS

Celia Stubbs, 2021

Ryder then moved on to talk about Celia Stubbs. She is a Core Participant because of her relationship with Blair Peach and led the campaign about his murder by police in 1979. Stubbs recently spoke movingly about it, and spycops, to Channel 4 News.

Peach and Stubbs were both members of the SWP as well as active anti-racist campaigners. Stubbs has campaigned all her life, always to strengthen civil society, and was targeted by the undercovers as a result. Both Stubbs and Peach had spycops files kept on them, opened in 1974 and 1978, long before Peach was killed. We have not seen any of the documents involved that pre-date Peach’s death.

On 23 April 1979, there was a plan to march and sit down at Southall Town Hall protesting at a National Front meeting. Special Patrol Group (SPG) officers piled out of a van and one struck Blair killing him.

All six SPG officers refused to cooperate with the investigation that followed.

Commander Cass’ report at the time confirmed a police officer had killed Peach and identified Inspector Alan Murray as the person most likely to be responsible. Illegal weapons and Nazi regalia were found in the lockers and homes of the SPG officers. Cass’ report was not published until more than 30 years later.

No officer was ever brought to justice for due to a major police cover-up. Officers refused to cooperate with investigations.

The Met told their lawyers to give a knowingly false version of events at Blair Peach’s inquest. They will have seen the Cass report that contained the truth, but still, they lied. The corruption extended beyond the police.

The killing of Blair Peach remains one of the most notorious events in British police history, a national disgrace, and a permanent stain on the Met.

An SDS annual report to the Home Office cites the death of Peach and the ensuing campaign for justice as a key focus for the unit. This is not about subversion or disorder. The Home Office’s response was to renew the SDS’s funding.

The SDS reported on the campaign for promoting actions like writing to MPs and local newspapers, and phoning in to radio shows. Again, this is not public disorder or subversive activity. A number of spycops even attended Blair’s funeral, while police evidence gatherers photographed the attendees for later identification by the SDS.

Combined with the cover-up, it is clear that the infiltration of the Blair Peach campaign was about preventing guilty police officers from being held to account.

THE SPYING HASN’T STOPPED

The spycops units have continued to take an active interest in the Blair Peach campaign ever since. A commemorative event was organised for the twentieth anniversary of his death in 1999, and this was targeted by spycops, with the excuse that such campaigns were ‘anti-police’. Justice campaigns were routinely portrayed as some sort of risk to public order even when they plainly weren’t.

Blair Peach

Campaigners for police accountability in cases where the police played a part were a major target for the SDS, and this continued for decades. Police admit undercover officers spied on at least 18 family and justice campaigns, and the true total is likely to be much higher. On our website we name thirteen examples that we are sure of and summarise these cases of police incompetence, arrogance and murder.

Police lawyers told the Inquiry last November that the SDS and NPIOU never directly targeted justice campaigns. But the documents we see in these hearings prove that is untrue. Officers were tasked to spy on the Peach campaign.

Why would the SDS highlight the Peach campaign to the Home Office if it were not a direct focus? Why are some reports only about the Peach campaign? Why were so many other campaigns targeted later? The denials of the police lawyers are simply not plausible. Their statement should be publicly corrected and withdrawn.

The 1979 SDS annual report describes the Peach campaign as a main focus, yet the Inquiry has disclosed suspiciously few documents relating to this.

It is striking that there is so little evidence relating to either the 1979 Southall demonstration where Peach was killed, not the 1974 Red Lion Square anti-racist protest at which Kevin Gately was killed. There is a real concern that reports may have been destroyed by the police in order to cover up the facts around both fatalities.

Earlier in this Inquiry, there were references made to a report about the Southall demonstration at which Peach was killed, This report – key evidence about an extremely important and relevant historical event – has still not been disclosed to us, and we are left wondering if it has been deliberately withheld from the Inquiry, or just not shared with us?

For Stubbs, this conspicuous lack of evidence is just one more obstruction to truth and accountability.

TRUTH, THE WHOLE TRUTH

Celia Stubbs was also involved in the Hackney Community Defence Campaign and Colin Roach Centre, both of which were targeted by spycops. She is extremely disturbed about the fact that her lawyers were put under police surveillance, and Special Branch files were opened on them.

This Inquiry has had police material for years, yet only passes it to witnesses shortly before the hearings, giving us little time to properly analyse and respond. The extremely limited opportunity for victims to question witnesses limits the Inquiry’s ability to get the truth.

Celia Stubbs and Blair Peach sought to bring people together and make a fairer world. They were spied upon. She wants answers and accountability. She does not have to prove her innocence; the state must show why it spied on her.

There is nothing in the police documents disclosed by the UCPI that justifies spying on Celia Stubbs.

Bringing the hearing to an end, Mitting reminded us that tomorrow is the 42nd anniversary of Blair Peach’s death. The Inquiry will resume at 10 am with Mitting speaking briefly about Blair Peach and then there will be a minute’s silence.

Full opening statement from Ernest Rodker, Professor Jonathan Rosenhead and Lord Peter Hain

Full opening statement from Celia Stubbs

<<Previous UCPI Daily Report (21 Apr 2021)<<

>>Next UCPI Daily Report (23 Apr 2021)>>

The third day of the 2022 Undercover Policing Inquiry hearings concerning the management of the Special Demonstration Squad 1968-82 included opening statements from:

The third day of the 2022 Undercover Policing Inquiry hearings concerning the management of the Special Demonstration Squad 1968-82 included opening statements from:

Morris mentioned one spycop, ‘Tony Williams’ (officer HN20), who became treasurer and secretary of the London Workers Group and whose reporting was no doubt passed on to the Security Service for blacklisting purposes. Apparently the SDS told the Security Service they considered Williams’ withdrawal from the field ‘no great loss’ as he had not been ‘particularly productive’.

Morris mentioned one spycop, ‘Tony Williams’ (officer HN20), who became treasurer and secretary of the London Workers Group and whose reporting was no doubt passed on to the Security Service for blacklisting purposes. Apparently the SDS told the Security Service they considered Williams’ withdrawal from the field ‘no great loss’ as he had not been ‘particularly productive’.

Yesterday the police told the Inquiry said they would have behaved identically if a racist campaign had opposed a black sports team touring England. But supporting racism is different from opposing it. Equivocation between the motivations and actions of the left and far-right was apparent in the witness testimony of Madeleine earlier.

Yesterday the police told the Inquiry said they would have behaved identically if a racist campaign had opposed a black sports team touring England. But supporting racism is different from opposing it. Equivocation between the motivations and actions of the left and far-right was apparent in the witness testimony of Madeleine earlier.