New Spycops Public Inquiry Chief Named

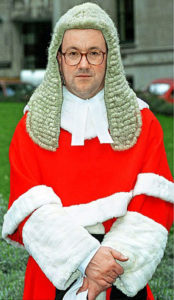

Sir John Mitting

Sir John Mitting has been appointed to take over as chair of the public inquiry into undercover policing.

It comes three months after the current Chair, Lord Pitchford, announced he has motor neurone disease and does not expect to be able to complete the inquiry. Mitting will work alongside Pitchford for the time being and will succeed him as chair at an appropriate time.

The inquiry was commissioned in March 2014 after years of revelations about spycops. The three years since have been characterised by police delays and obstructions, and the inquiry has still yet to formally begin.

As a High Court judge, Mitting has had a little involvement with the issue before, ruling in a March 2015 hearing of the case brought against police by activists abused by undercover officer Marco Jacobs.

On that occasion, he orchestrated an ingenious solution to the problem of police saying they would ‘neither confirm nor deny’ (NCND) if Jacobs was their officer. Mitting got them to agree that, while they would not officially drop their stance of NCND, neither would they contest the activists’ assertion that Jacobs was an officer, and if damages are awarded then the police will be liable to pay.

However, there are many elements of Mitting’s professional and personal life that cause serious concern.

JUDGE IN SECRET SPY COURTS

He is vice-president of the Investigatory Powers Tribunal (IPT), a bizarre secret court dealing with government surveillance cases. It was formed in 2000, when the state realised that surveillance authorised under the new Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act may breach human rights or other law.

Most of its claims are held in secret and not even the spied upon citizen is allowed to be at the hearing. Their lawyers don’t get to be at the hearing either. There is no chance to cross-examine. Complainants just send some papers to the court. In contrast, the police (or whichever state body is accused) and their lawyers are allowed to be at the hearing. The citizens and their lawyers do not get to see what’s in the state’s submissions – they may omit evidence that incriminates them, or invent evidence about the citizens. The court then considers the case and makes a decision. It gives no reasoning for its decision. It doesn’t even have to confirm whether the citizens were under surveilance. The citizens cannot appeal the judgement.

It’s unsurprising that it finds in favour of the state over 99% of the time. Between its formation in 2000 and 2012, the Investigatory Powers Tribunal upheld 10 complaints out of 1,468.

Kate Wilson, who was abused by undercover officer Mark Kennedy, has a case pending at the IPT.

From 2007-2012 Mitting sat as a judge in the Special Immigration Appeals Commission. This is another Kafkaesque secret court, dealing with applications to deport people accused of being a threat to national security.

The cases are based on secret evidence which has never been heard by either the appellants themselves or their lawyers. In many of the cases, a return to their country of origin would be likely to result in detention and a high risk of torture.

Whilst Mitting was involved in a number of cases, the judgements that have come to prominence are ones that have been unpopular with the press, such as ordering the release of Abu Qatada and preventing the deportation of an Algerian terror suspect on humans rights grounds.

INSTITUTIONAL SEXISM

Mitting’s entry in Who’s Who reads:

MITTING, Hon. Sir John Edward

Kt 2001

Hon. Mr Justice Mitting

Born 8 Oct. 1947; s of late Alison Kennard Mitting and Eleanor Mary Mitting; m 1977, Judith Clare (née Hampson); three s

a Judge of the High Court of Justice, Queen’s Bench Division, since 2001

Education

Downside Sch.; Trinity Hall, Cambridge (BA, LLB)Career

Called to the Bar, Gray’s Inn, 1970, Bencher, 1996; QC 1987; a Recorder, 1988–2001; Chm., Special Immigration Appeal Commn, 2007–12; Vice-Pres., Investigatory Powers Tribunal, 2015–Recreations

Wine, food, bridgeClub

GarrickAddress

Royal Courts of Justice, Strand, WC2A 2LL

The mention of the Garrick Club is noteworthy. It’s an elite London ‘gentleman’s club’ that is one of the last to prohibit women from becoming members. That a bastion of codified sexism is Mitting’s choice of environment is of serious concern as he takes charge of an inquiry with institutional sexism and abuse of women at its core.

Incidentally, the Garrick Club was the scene of a confrontation between Mitting and former Conservative MP Andrew Mitchell, who Mitting had ruled against in the Plebgate case, ordering him to pay substantial damages to a police officer Mitchell had insulted.

The appointment of a spycops Chair whose past is at odds with the aim of the public inquiry does not necessarily doom the process to failure. When the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry were given Sir William MacPherson, the family campaign saw his history regarding cases with racial elements and tried to have him removed. They failed, yet MacPherson appeared truly outraged at what he found and issued a damning report that forced the police to admit they were institutionally racist, and recommended reform of state institutions far beyond the police.

WHICH KIND OF CHANGE?

With Pitchford stepping down, there is an opportunity to change the structure of the inquiry. As the Hillsborough families showed, even with its most powerful tool – a judge-led public inquiry – the state is not very good at investigating state wrongdoing.

The Child Sexual Abuse inquiry which, like the undercover policing inquiry, was commissioned in 2014 but has yet to properly begin, has lurched from crisis to crisis and is now on its fourth Chair.

The Stephen Lawrence Inquiry had the benefit of a panel of lay members, familiar with the issues, who played an important role in adding a broader dimension to the chair’s work. The undercover policing inquiry covers many of the same issues as the Lawrence inquiry (and indeed the Lawrence campaign and family themselves). It also deals with abuse of people who have been campaigning against state and other power. To be effective it must have input from people who understand those perspectives and subcultures.

This inquiry is not about mere serious allegations of officers’ wrongdoing, but proven and systemic abuse of citizens. It is not there to arbitrate between police and activists, but to uncover the full facts of this victim/perpetrator situation. The voices of the abused must be heard above the police who lied for decades and, since discovery, have done all in their power to avoid accountability and keep the truth hidden.