UCPI – Weekly Report 13: 21-24 October 2024

Tranche 2, Phase 2, Week 2

21-24 October 2024

This summary contains descriptions of child deaths, serious injuries, and a strong racist slur.

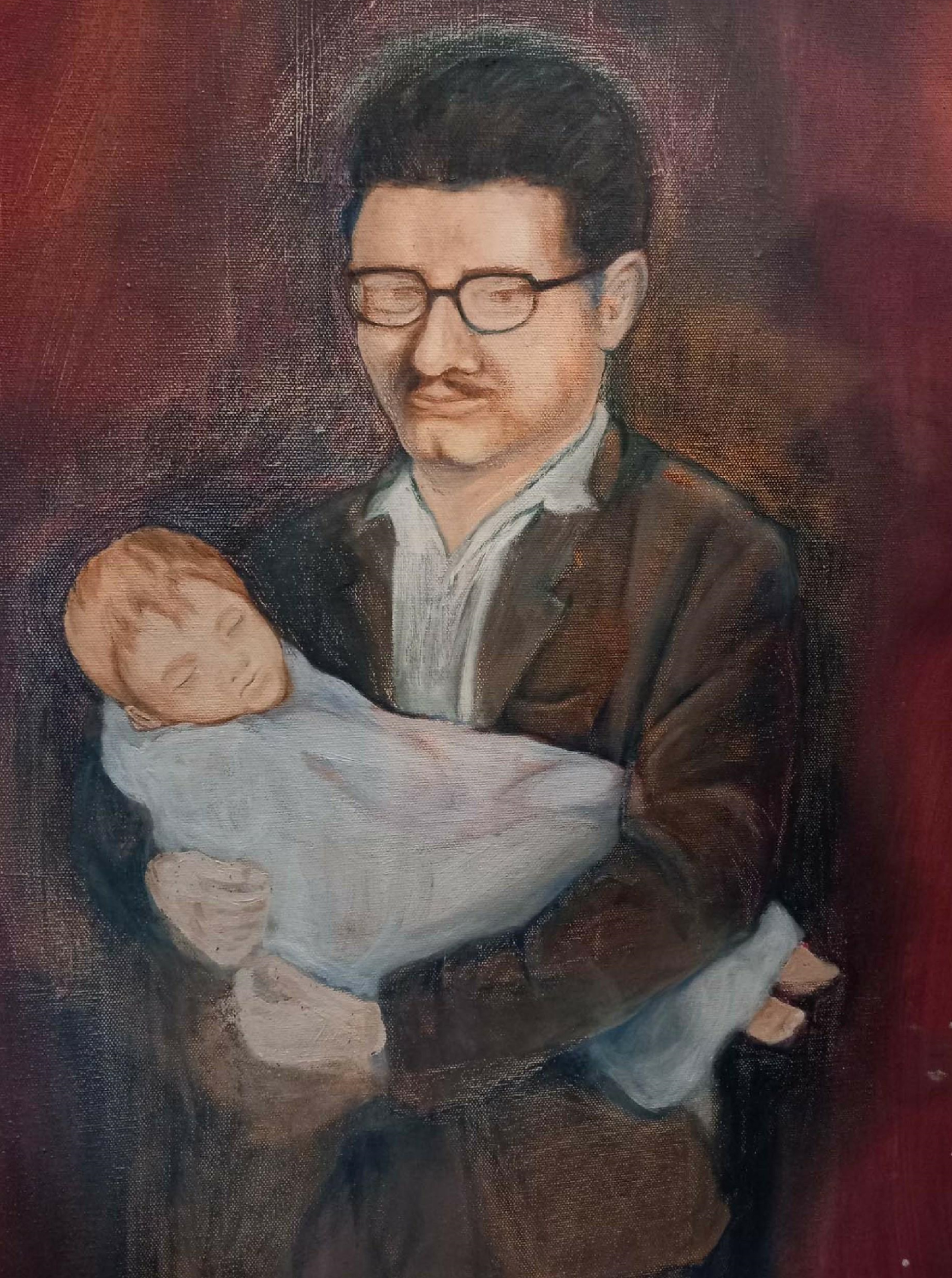

Painting by Kaden Blake – the last time she saw her brother Matthew Rayner, in their father’s arms. Matthew’s identity was stolen by officer HN1.

The summary covers the second week of ‘Tranche 2 Phase 2’, the new round hearings of the Undercover Policing Inquiry (UCPI), examining the animal rights-focused activities of the Metropolitan Police’s secret political unit, the Special Demonstration Squad, from 1983-92.

The UCPI is an independent, judge-led inquiry into undercover policing in England and Wales. Its main focus is the activity of two units who deployed long-term undercover officers into a variety of political groups; the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS, 1968-2008) and the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU, 1999-2011). Spycops from these units lived as activists for years at a time, spying on more than 1,000 groups.

INTRODUCTION

The week brought a lot of harrowing testimony from people whose children died in awful circumstances, and whose agonies were then intensified by the abuses of the Special Demonstraton Squad.

Before that, the first day of live evidence in this set of hearing was not broadcast. Proceedings were covered by strict reporting restrictions, so there is very little we can say at this time about the evidence of ‘ZWB’. He was a civilian witness. The Inquiry has said it will be producing a ‘gisted transcript’ of his evidence, but it has not yet done so.

The evidence that was broadcast this week was truly harrowing stuff. Witness after witness was made to relive deep family tragedies, in order to recount the awful behaviour of the police towards their families. They did so with overwhelming dignity and grace.

The one exception was Wednesday’s evidence from officer HN122 ‘Neil Richardson’. His real name is protected and the cover name he used was stolen from someone’s dead child, who you can read about below.

There was no video feed of his evidence, in order to protect his identity, and the audio broadcast was outstandingly dull. Nevertheless the Inquiry sat late that day. He is the last officer we will hear from until HN10 Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’ gives evidence (2-5 December).

Many of the officers in this tranche, examining 1983-1992, have refused to appear.

This week (beginning Monday 28 October) is half term so there are no hearings.

Live evidence hearings return on Monday 4 November with the evidence of Martyn Lowe.

CONTENTS

Kaden Blake, sister of Matthew Rayner

Faith Mason, mother of Neil Martin

HN122 ‘Neil Richardson’

Richard Adams, father of Rolan Adams

John Burke-Monerville

Tuesday 22 October 2024

Evidence of Kaden Blake

Click here for video, transcripts and written evidence

Matthew Rayner, whose identity was stolen by a spycop, with his father

Kaden Blake is one of four children. Matthew Rayner, her youngest brother, died when he was four years old.

His identity was stolen by the Metropolitan Police Special Demonstration Squad to create the cover identity of officer HN1, who got a criminal record and abused a woman while using Matthew’s name.

Kaden gave oral evidence remotely, supported by her partner. She has also provided a 28-page written statement with exhibits, including photographs of Matthew as a child, letters and Kaden’s own artwork showing the end of her brother’s life, in his father’s arms.

She was about nine when Matthew was born.

He was a a calm baby, not fractious, even when he became ill:

‘I loved helping out my mum and looking after him, and just watching him play.’

Matthew was around two years old when he became poorly. The diagnosis was leukaemia.

He had short stays in hospital, but his father tried to keep him at home as much as possible. It was very difficult for the family.

‘we didn’t know how ill he was but obviously my parents did so it must have been an incredible strain on them…

‘it was difficult to live around that as a child… at my age I hadn’t necessarily processed in my mind that it – you know, that he would die… I just thought he would get better…

‘over time obviously I did realise that he was getting progressively ill. Just looking at him you could see that…

‘it was difficult to have a normal childhood… because it was always in the back of your mind.’

In early 1972, after many unsuccessful treatments that had increased Matthew’s suffering, his parents made the agonising decision to bring him home.

On 25 January 1972 he died in the family home.

The family moved out of the house shortly afterwards.

‘[it was] mostly my father’s decision, my mother wasn’t capable really at that point in time… it must have been the way my father intended to cope with things I think… And he perhaps thought he was protecting us from any more pain.’

However, for Kaden it was as thought she never got to say goodbye. They moved around for months, stopping in bedsits.

The Inquiry asked about her mother.

‘She was devastated isn’t a good enough word, it’s not… I even remember distinctly her saying that she didn’t feel that she could ever laugh again. That’s how she felt at the time and now I understand it but hearing that as a child as well made you feel totally inadequate… I know that wasn’t her intention at all and that was her grief speaking…’

Kaden and her brothers didn’t dare talk about Matthew after he died because of how much it hurt her mother:

‘we just wanted to save her from any more pain.’

In the early 1990s the family home was burgled. A few days later a small cardboard box was left near the gate. It was her brother’s ashes.

‘whoever took them obviously realising what it was at least had the decency to return them.’

Seemingly there was more honour among house thieves than in the identity theives of the Special Demonstration Squad.

Matthew’s identity was stolen by officer HN1 as his cover identity during his infiltration of the animal rights movement in London between 1992 and 1996.

In 2018 an official-looking gentleman showed up at Kaden’s door to let her know.

‘It felt unreal… I didn’t know what reaction to give. I’d never heard anything like this before.’

Her brother James has written a letter to the Inquiry setting out how the news affected him. Both her parents had already passed away.

‘My mother would’ve taken it really badly. My father was a strong stoic person so his reaction could have been different, could have been quite angry actually. But my mother would’ve been mortified so at least she was spared that.’

Officer HN1 chose Matthew’s identity from the register of births and deaths.

He described the process in his witness statement, going to the Registry and finding a few death certificates of children of roughly the same age which he submitted to the Special Demonstration Squad’s back office, who would eliminate unsuitable names from the list.

‘They would do checks to make sure you had not selected a person whose parents were traceable or otherwise posed a risk of detection. Once approved the name was used as a cornerstone of documentation’

Kaden says that description makes her emotionally sick. She also notes that her parents were easily traceable at the time, so it doesn’t make sense.

She also commented on HN1 visiting Sheffield for a day, to shore up his back story.

‘That felt really strange and sort of creepy and then I was wondering if he’d been to the house, 44 Psalter Lane, and then any schools or anything. I didn’t know how far he’d taken it.

‘I know he said he only went there once but to think that he possibly went to the actual house where we were living at Matthew’s death is very unpleasant to think about that…

‘did he find out what schools we all went to, did he mention our names, you know, the siblings all my siblings’ names as well, in conversation? Which does naturally occur if you’re talking to somebody. You say do you have any brothers and sisters. And that felt really creepy, really creepy.’

HN1 used to celebrate his ‘birthday’ using Matthew’s date of birth.

‘it feels so raw… that should have been a family occasion for the real family, not for somebody pretending to be him.’

We were shown a document (MPS-0746169) outlining HN1’s cover identity: It sets out the name and date of birth of Matthew Edward Rayner, born 16 September 1967, the address where he was born, details of his parents: father, Allen Alfred Rayner, with his date of birth, his job, and his parents names; and mother, Florence Jean Rayner, maiden name Smith, with her date of birth and the details of her father, his occupation and her mother.

There is a note which says:

‘All grandparents now deceased. Father is now retired and both parents now live at Thorganby House, Thorganby North Yorkshire.’

This was all real information about the family in 1991-92 and includes far more detail than would be found on a birth or death certificate, suggesting detailed and invasive research was done into the bereaved family.

It also shows that the family were not only traceable, but traced by police. The risk to the family that someone who was spied on by the officer and became suspicious could have shown up looking for ‘Matthew’ was obviously very real.

The questioning then moved on to HN1’s actions during his deployment. He was arrested in 1995 and charge with threatening behaviour. Kaden described this as ‘horrible’.

The arrest took place in North Yorkshire, the county where her parents were living. She pointed out:

‘the name could have been mentioned in or on the press [for being arrested].’

It could have put her parents, particularly her mother, at risk of great upset. Yet the hearing was shown an internal management document which stated:

‘This incident presents us with no particular difficulty; the officer maintained his cover and is none the worse for his short incarceration. Indeed we may well accrue longer term benefits from his arrest in terms of contacts made and intelligence gleaned.’

Meanwhile, somebody with Kaden’s brother’s stolen name now had a criminal record.

HN1 also appeared in court as a defence witness during his deployment giving evidence using Matthew’s name.

Kaden said:

‘I’d like to wash his mouth out with soap.’

HN1 entered into a relationship with a woman, Denise Fuller, whilst he was undercover, yet another sullying of Matthew’s name.

Kaden expressed sympathy for the woman involved and added:

‘It’s a very, very surreal thing to think about… if my brother lived he should have had a proper relationship with somebody. You know I’d have had nephews and nieces hopefully, you know, and a sister-in-law but that was obviously never to be.’

HN1 was asked about using Matthew’s identity. His witness statement was read aloud:

‘I have been asked whether consideration was given to the particular personal circumstances of the bereaved family and the likely consequences for them if the use of their loved one’s identity became known to them or to others. This consideration did not feature in my conversations with the back office.’

Kaden responded:

‘He says “loved one’s identity”, well, I hope he realises what that means.’

Counsel to the Inquiry then read from the Special Demonstration Squad tradecraft manual:

‘By tradition the aspiring SDS officer’s first major task on joining the back office was to spend hours and hours St Catherine’s House leafing through death registers in search of a name he could call his own.

‘On finding a suitable ex person, usually a deceased child or young person with a fairly anonymous name the circumstances of his or her untimely demise was investigated.

‘If the death was natural or otherwise unspectacular and therefore unlikely to be findable in newspapers or other public records, the SDS officer would apply for a copy of the dead person’s birth certificate.

‘Further research would follow to establish the respiratory status of the dead person’s family, if any. And, if they were still breathing, where they were living.

‘If all was suitably obscure and there was little chance of the SDS officer or more important one of the wearies running into the dead person’s parents/siblings et cetera the SDS officer would assume squatters’ rights over the unfortunate’s identity for the next four years.’

(Emphasis added by Kaden Blake for her witness statement)

Kaden commented on this:

‘My brother’s memory was abused and all our grieving meant for nothing, and some of the words used are extremely callous…

‘they looked at so many death certificates of children, did it not tweak any emotions in them of what they were doing? They were looking at people’s utter grief, and where that didn’t matter, because although these children are dead they’ve had such impact on the relatives…

‘it affects the rest of your life, your behaviour, your self-worth, everything… such a callous way of doing things and like I’ve said before for such a — I’m not saying invaluable reason but very low value reason I think.’

Kaden Blake was offered an apology from the police. She did not accept it.

The Metropolitan Police apologised anyway, but she was very clear:

‘I feel it’s worthless and it is only, you know, in hindsight that they’ve issued it… they’re saying they didn’t realise the hurt that it will cause until after they were told the hurt it caused. Any human being surely has compassion and has the ability to put yourself in a situation…

‘It’s an extremely callous thing, not to be able to put yourself in in somebody else’s situation especially grief.’

At the end, the Inquiry Chair, Sir John Mitting, made a point of personally thanking Kaden Blake for giving live evidence:

‘It brings to life what the use of a technique, which I think all now accept should never have been used by a police officer, can have on real people.’

He also acknowledged the distress caused by the Inquiry alerting her to the use of her brother’s name.

Officer HN1 is expected to give evidence on 6, 7 and 8 January next year.

Evidence of Faith Mason

‘I am desperate to find out the truth of what happened and get justice for my Neil.’

Faith Mason

Officer HN122 infiltrated Class War and the Revolutionary Communist Party from 1989 to 1993 using the name Neil Martin Richardson, an identity stolen in part from a boy, Neil Martin, who died young of a rare disease.

In 2019, the Solicitor to the Undercover Policing Inquiry turned up on the doorstep of Neil’s mother, Faith Mason, to inform her. The news was devastating.

Faith Mason did not give live testimony. She provided a written statement to the Inquiry, but she was not called to give evidence, nor were her words summarised to be read onto the public record. The statement was simply released on the Inquiry website.

Nevertheless, we have opted to including a summary of her powerful testimony here.

Neil Robin Martin was born on 5 September 1963 in County Durham. Faith was 16 at the time. Neil was a happy baby, but after she gave birth to her second child she started noticing issues:

‘He would start throwing his leg out to the side, would not walk properly and would limp.’

She made an appointment for Neil at the local doctor’s surgery to find out what was wrong. The doctor initially said there was nothing wrong, but Neil got worse.

‘I found it so hard to be taken seriously… they just would not listen to me. It makes me sad to think that most of Neil’s short life was spent in doctor’s appointment after doctor’s appointment, tests after tests and constant trips in and out of hospital… His condition seemed to baffle doctors, who could not work out what was wrong.’

Neil’s health declined and he was in hospital for long periods, kept physically apart from his mother:

‘He could not walk. His spine was bending up and his back was arched over. He could only move around by dragging himself on his bottom. His hands were all rough from him having to drag himself everywhere. The skin on his hands became very thick, like a pig’s hoof…

‘once, he was sat on the sand, watching the builders and his brothers, and he looked at me and said “I can’t walk like them.” It broke me.’

Neil was completely disabled by the summer of 1969. A doctor told her he was ‘going downhill.’

‘I just kept saying “no, no, no, no”. I refused to believe it… I just believed he was going to live, even though the doctor was telling me he was going to die. I just would not accept it.

‘The day before Neil’s passing was a strange day. I remember feeling very happy and hopeful as Neil seemed to be doing well…

‘I had Neil in my arms. The song “He Ain’t Heavy, He’s My Brother” by The Hollies was playing on the radio. I was holding Neil close to me, singing to him, “He’s not Heavy, He’s my Son”. He was laughing and smiling. I was so happy. I thought he was on the mend.’

She had been in the hospital for a week, refusing to leave Neil’s side, sleeping in a chair. That day, a doctor convinced her to go home and get a proper night’s rest. At 7.45am the following morning police officers knocked on her door to tell her Neil was unwell and she should go to the hospital.

‘I arrived at the hospital and rushed down to Neil’s room and saw a nurse and a doctor standing outside. I knew then that he had died.’

Neil passed away in his sleep, aged six years old, on 15 October 1969. A post-mortem showed he had Progressive Cerebral Sclerosis – a rare disease, especially in children.

‘My heart shattered when Neil died… My flat was just opposite the cemetery… I would go to the cemetery every single day and just sit with Neil from morning till night… I couldn’t bear thinking of him being alone in the cold. This lasted for months and months…

‘There were some days I would climb into the cemetery at midnight just to sit with him. Over the years I visited the cemetery less frequently, but knowing where Neil was and where his gravestone was, was of deep importance to me.’

On 13 January 2019 there was a knock on her door. Piers Doggart, the then Solicitor to the Inquiry, explained that a Metropolitan Police officer had stolen Neil’s first and middle names and date of birth to create the fake persona Neil Martin Richardson.

‘It felt like I had crashed into a brick wall. I was in a state of absolute shock. Mr Doggart was talking to me and explaining, and I was listening but I was not really hearing the words…

‘I just could not believe that in this day and age someone could do something so vicious and heinous as that, especially policemen.’

The news impacted her so much that she went to see a doctor in April 2019.

‘I would say that the stress, upset and anxiety caused by finding out about this situation has put my health in serious danger…

‘I am a 72 year old woman… I am grieving Neil all over again… There is something particularly painful about an adult man taking my Neil’s identity, to live in a way that he would not have lived. I wanted so desperately for my Neil to get to grow up, but he couldn’t.

‘HN122 took that future and lived it as if he was Neil, and that makes the loss all the worse…

‘I am back to a place where I can no longer speak or think about Neil without feeling absolutely heartbroken and breaking down… any happy memories that I was able to enjoy about my Neil only feel painful now since finding out about HN122.’

HN122 also went to Durham to research the identity.

‘I have been told that the officer might have looked up background information about Neil. I realised that the officer could have visited Neil’s grave. This horrified me as Neil’s grave was the most special place to me…

‘it made me feel like the police had dug up Neil’s body and stolen it… for a long time I could not go back to the cemetery as it was too painful. In February 2023 I had Neil’s headstone replaced. It felt like some closure and some healing, after feeling all my memories had been tainted by HN122.’

Neil’s uncle was a policeman. She used to look up to the police, admiring the work they did.

‘every time I see a police officer now, I feel like shaking them and asking them “do you know what you have done to me?”…

‘I do not want to be someone that feels bitter towards the police, but learning about the Inquiry and what all these officers did, and the more you hear on the news, it is hard not to.’

She criticised both undercover officers and their managers:

‘These were adult men in positions of power that should have had consciences to speak up about doing something wrong. If we cannot trust police officers to challenge things that are immoral and cruel to innocent children and their families, who can we trust?’

In November 2021 Faith lost another son, Paul, to a heart attack. He is buried next to Neil. She feels she has not been able to grieve him properly due to the impact of the grief she was reliving over Neil.

She had hoped HN122 would express remorse as Peter Francis did, however HN122 merely said that he did not intend to cause offence but the use of such identities was a necessity and was carried out for legitimate purpose.

To this she says:

‘I am not offended, I am horrified and devastated and feel that my child and his memory have been tainted. I feel that HN122 used the most awful tragedy to his advantage, treating my child’s identity like it was nothing. What ‘legitimate purpose’ could there possibly be?’

Like Kaden Blake, Faith also referred to the horrible language used in the SDS Tradecraft Manual.

‘My Neil was not an “ex-person” whose name HN122 could call his own. He was a real child who suffered and deserved to live. His unexplained, incurable illness and death were not ‘unspectacular’; they were tragic and traumatic, impacting my whole life…

‘It is as if the police as a whole and the SDS officers specifically did not see us as human beings, but just objects to be used as they liked, and to be joked about. It is so disrespectful and dehumanising.’

Faith is clear in her position about apologies from the police.

She told the BBC four years ago

‘I don’t want an apology, I just want to know who stole my little boy.’

In 2024, she is no nearer the truth. And she is still adamant:

‘I don’t want an apology, I want the truth. The more I find out about the practice of taking deceased children’s identities, the more I feel that the police are only apologising because they have been caught…

‘they are just saying sorry because they know normal decent people are horrified by what went on, and they don’t want to get into more trouble…

‘What I want is accountability from the police and for the Inquiry to facilitate me and other families in getting answers’

She believes the personal safety of herself and her family was put at risk.

‘I have seen that so many officers have been granted anonymity by the Inquiry because they have said their personal safety would be threatened…

‘There was no thought about my family’s personal safety, let alone respect for our private and family life. And there is no consideration of my right to know the real identity of the man who stole my child’s identity. It seems to me that it would be justified and proportionate for me to know this, but I have not been allowed.’

She wants justice and answers for her son and for all the other families.

‘I think of the other families often. I know there are lots of families who did not feel able to participate in the Inquiry, who may not even know that their loved one’s identity was stolen.

‘I feel that I am seeking answers and justice for those children and families, as well as for my Neil. I am grateful for all the other families who are fighting for this alongside me.’

Wednesday 23 October 2024

Evidence of HN122 ‘Neil Richardson’

Click here for video, transcripts and written evidence

Wednesday’s hearing was devoted to the oral evidence of one of the spycops, HN122 ‘Neil Richardson’. He appeared in person, and was questioned by one of the Inquiry Legal Team (barrister John Warrington) about his time in the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS).

HN122 was deployed undercover for four years, from 1989–1993. He was tasked first with infiltrating the Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP), and then Class War. He spent a number of years in Special Branch, and was approached in late 1988 about joining the unit.

Recruitment and training

According to the SDS’s Annual Report, sent to the Home Office in May 1989, the unit’s DCI had been told to review ‘recruitment, operational deployment and supervisory aspects’, and as a result there were now ‘selection criteria’ in place, to ‘ensure that potential recruits were equipped psychologically and emotionally to cope with the pressures of this posting’.

However the recruitment process described by HN122 consisted of an informal interview with DCI Gray and another manager (HN109). He was told that his deployment would run for 4-5 years, and would entail a lot of time away from home.

In his witness statement, supplied to the Inquiry in 2021, HN122 said he considered it:

‘an honour to be thought capable of gathering intelligence because this was the pinnacle of Metropolitan Police Special Branch work’

However, he said that he was not confident about his ability to do it. They reassured him about this, and said he could walk away if it didn’t work out.

These two also paid him a home visit, and asked him and his wife some general questions about how long they’d been married, but there was seemingly no in-depth assessment, formal testing or psychological evaluation. It was considered important to check that an undercover’s family would pose no security risks, and carry out basic background vetting.

Standard SDS procedure was for new recruits to spend about six months in the back office, familiarising themselves with their target groups and creating their cover identity. During this time, they would have the opportunity to talk to the officers who were already in the field, and see their reporting. There was ‘intensive discussion’ but no training as such.

He says he was not given any guidance about how much he could or should involve himself in his targets’ lives, or where to draw the line.

He thought it was fine to visit homes, meet families and socialise with them, saying ‘it was a necessary part of the job to become on friendly terms with these people’ but says that he had no intention to form ‘intimate relationships’ with anyone he spied on.

HN122 says in his statement that he only saw the SO10 ’Code of Conduct for Undercover Officers’ after his deployment had ended. Despite being provided with a copy when he wrote his statement, over three years ago, he says now that he still hasn’t read it ‘in detail’. There was no other training, manual, or written guidance, to prepare him for his new role.

Sexual relationships

Asked about officers having relationships while undercover, HN122 stated that it there was an obvious risk of extra-marital affairs occurring in any job which entailed men working away from home for long periods of time, and it would be ‘naive’ to think otherwise.

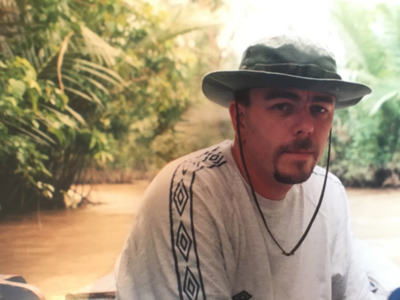

HN15 ‘Mark Cassidy’ Mark Jenner in Vietnam on one of the holidays he took with Alison, who he lived with for 5 years. Officer HN122, Jenner’s mentor, says he was totally unaware of the relationship.

He was able to come up with a list of tactics to rebuff any advances. He says he never discussed this issue with his managers, and only did so with one other SDS officer, who shared his view that such behaviour would be morally wrong.

He claims not to have known – or even heard any rumours about – about any SDS officer ever having such a relationship, with the exception of HN11 Mike Chitty ‘Mike Blake’ (deployed in the 1980s) during his time in the unit.

He says he ‘had no idea’ and was shocked to later learn that many (at least seven) of the officers who served at the same time as him had done so. He was interviewed by ‘Operation Herne’ (an internal police spycops inquiry) in 2013, and the handwritten notes taken then suggest that he knew that HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’ had a relationship with Helen Steel.

We heard that the SDS operated an informal mentoring scheme. Those who joined the unit were given a ‘point of contact’ – a more experienced officer they could call on for advice.

HN122’s ‘mentor’ was HN19 ‘Malcolm Shearing’; they met in a pub for a chat every six months or so.

Later on, he served as the point of contact for another undercover: HN15 Mark Jenner ‘Mark Cassidy’. According to HN122, Jenner was reluctant to meet up or engage. The scheme was just supposed to offer an extra ‘channel’ of support for officers who needed it, so he didn’t feel it was appropriate to push it, and their meetings petered out within a year or so.

He says Jenner didn’t confide in him about any problems, in his personal life or in his work. He certainly didn’t mention that he’d started living with ‘Alison’, the woman he deceived into a long-term relationship, and had even gone travelling abroad with her.

HN122 is adamant that there were no indications of this, and that he didn’t learn about this relationship until it became public knowledge, many years later. He said if he’d known at the time:

‘Well, I’d like to think I would’ve reported to the office immediately’.

Other inappropriate conduct

He admitted regularly staying over at activists’ homes, especially during his time in Class War.

In 1991, he was invited to the wedding of an RCP supporter, and attended it, claiming that the bride-to-be thought he was ‘not as fanatical’ as the Party members, who she felt ‘intimidated’ by. Under questioning, he admitted that he could have made up an excuse rather than intruding on such a personal occasion.

Although HN122 understood the phrase ‘legal privilege’ (as referring to confidential communication between a lawyer and their client) he doesn’t remember any training about this issue after he’d joined the SDS. He freely admitted that if he’d come across any such information he would have put it in his reports anyway.

He says he never received any feedback about the content of his reports, and always included all the ’relevant’ details, but never used his own judgement about what was appropriate. He left these decisions to more senior officers.

Reports were routinely ‘sanitised’ (stripped of information that might identify the ‘reliable source’, i.e. the undercover) before being sent to their ‘consumers’, but he claims to have only done this ‘under supervision’, when he worked in the back office.

He felt that taking part in ‘low level’ criminality, such as fly-posting, in his cover name was acceptable. He said he believed that if he was caught doing so, he should give his cover name, and the office would pay any fine that resulted.

However, he says he hadn’t thought about how this could entail misleading a court – something that the Home Office insisted should never happen under any ircumstances, even if it meant an officer’s depoyment beng ended early or their cover being blown.

Asked about racism in the Met, he said he witnessed police officers outside of Special Branch making ‘derogatory comments about Black or Asian people’, and claimed that he would challenge and report them.

However he denied that there was a problem with the fact that Special Branch had a ‘Blacks and Browns desk’. According to him, its remit was to study a range of anti-racist groups because they were ‘victims of extreme left wing infiltration’. He repeatedly claimed that the groups themselves (most of whom were engaged in police monitoring) were not the police’s focus, saying the desk’s name was ‘simply shorthand’.

Similarly, he openly admitted hearing police officers making derogatory comments about women, but claimed that he didn’t encounter this kind of sexism within the SDS.

Creating his cover

Like other spycops, HN122 trawled through the records at St Catherine’s House to find details of a suitable deceased child’s identity, eventually selecting that of Neil Robert Martin.

Faith Mason and her son Neil Martin whose identity was stolen by officer HN122

In what he seemed to consider clever tradecraft, he combined that child’s first name and date of birth with a different surname, lifted from somewhere else. He claimed this gave him a ‘safety net’, that this would make it harder for anyone to find the birth certificate but still allow him to obtain a particular document.

He says that although he felt ‘uncomfortable’ about using any part of a dead child’s identity, and ‘it would have been much preferable’ not to do so, he felt he had ‘no option’.

The Inquiry then told him about other SDS officers (including the one he mentored, HN15 Mark Jenner ‘Mark Cassidy’) who used wholly fictitious names. Having now seen the statement provided by Neil Martin’s mother, he says he is aware that ‘an apology would not assist her’.

He knew that unlike some other groups, the RCP took security very seriously. Each branch had a security officer, and new supporters were interviewed, their identity documents and address checked. They would be invited to attend meetings, and political education sessions, but not everyone was then selected to become a Party member.

HN122’s cover ‘legend’ was that he worked as a carpet cleaner, so an RCP member invited him to do this at their house. He snooped around while he was there and came across a list of supporters, which he copied and included in his report. He couldn’t explain what lawful authority he had to do this; he claimed that this was this a ‘perfectly legitimate way of operating’ as the rules only applied to ‘evidential searches’ and this was a case of him searching for intelligence rather than evidence, a defence which prompted audible reactions from the public gallery.

Reporting

Many RCP activists had aliases that they used within the party, and HN122 considered figuring out their real names to be one of his main roles, saying this information would have been important ‘for vetting purposes’.

He estimated that he’d produced between 400-500 reports during his four years undercover. The Inquiry has unearthed some of these. He included all sorts of information about individuals: their education, employment, living arrangements, intellect, interests, parentage, death, bereavement, relationships, marriage, pregnancy, children, wider family, attraction to others, sexuality, serious illness, alcoholism and drug use, victims of crime and previous criminal conduct.

Some of the reports and photographs he submitted related to under-18s, including teenage supporters of the RCP. One such report related to a school boy, described as ‘an immature individual’.

Another of his reports suggests a teenage school girl’s recruitment may have been due to a ‘crush on her teacher’.

When questioned about these, he retorted that they were young people rather than children, insisted that they were a threat as they were bound to become full members of the Party in future, and caused a stir with his claim that in this second case ‘there are obviously safeguarding issues that needed to be addressed’.

Even the Inquiry’s barrister raised an eyebrow at this, asking pointedly if safeguarding fell ‘within the SDS remit’?

We also saw a report about a young woman which noted that she was a ‘lesbian’. Asked why her sexuality was included, HN122 said it was to help with identification, going on to add that vetting was different back then, and ‘you’d have to ask the Government’ why sexual orientation was ‘one of the criteria set for national vetting’.

We were shown some reports about public order situations involving the RCP, sometimes in the guise of their front organisations, such as the ‘Hands off the Middle East’ (HOME) committee or ‘Workers Against Racism’ (WAR).

HN122 sometimes acted as an RCP steward at demos, and was part of a ‘protect the banner’ group at an anti-racism march in November 1991, when the WAR contingent tried to run an alternative rally in Altab Ali Park, and were attacked by some Class War people. He said if there was disorder he ‘would have to act the part’ but tried to avoid committing any offences.

He considered the RCP to be ‘subversive’ but not much of a threat to public order.

By the beginning of 1991, the Security Service had decided that the RCP wasn’t much of a threat to national security either. There are reports of them meeting with SDS managers and saying they were now only really interested in hearing about the activities of another of RCP front, the Irish Freedom Movement (IFM).

HN122 supplied reports about several IFM events that year but says his managers never told him to stop reporting on the RCP, and he wasn’t redeployed elsewhere until a whole year later.

Spying on a very different group

In early 1992 he was retargeted to spy on a completely different group, Class War, and we heard more about this in the afternoon session. His transition from one group to the other was rushed, taking weeks instead of the three months he requested, because there were worries about Class War holding another ‘Summer of Discontent’ that year.

He says the Class War Federation (CWF) was disorganised and divided. He travelled around the country for Class War meetings and demos, taking a sleeping bag so he could stay on activists’ floors (and memorably once in the home of Chumbawumba band members).

He was at the national conference in Leeds in November 1992; he reported the split (‘considered permanent’) caused by Tim Scargill’s departure from the organisation. Scargill is said to have taken ‘roughly half of the useful membership’ (estimated to be 20-25 committed people) with him. According to the ‘consumer comments’ section, the Security Service considered this report ‘most useful’.

The SDS went on to produce a fuller briefing entitled ‘Developments in the CWF’ that December, which described the rift, and the two factions that emerged, in more detail. Scargill is said to have wanted a ‘more disciplined’, committed group with more structure, and a more ‘rigorous and energetic approach’.Its conclusion is that his group ‘will be the dominant one’.

HN122 says that following this report, he was tasked to stick with Tim Scargill, who he was already close to. However Scargill’s new Class War Organisation (CWO) dwindled in size until there were only three core activists left, all based in London – Tim, ‘Neil’ and one other.

It’s been alleged by a witness involved in Class War at the time that ‘Neil’ had ‘played an active role’ in its break-up, but he denies this. He admits that it became increasingly hard not to ‘influence’ the group as it got smaller. He represented Class War at anti-racist networking meetings, and wrote what he says was an ineffective industrial strategy for them.

The end: his exfiltration

It is clear that neither the CWF or CWO really recovered from the implosion, and even the SDS managers seem to have realised there was little point in continuing to spy on them. In June 1993, they told the Security Service that HN122’s deployment was due to end in September, but it’s unclear when the officer himself was told.

A former member of Class War, Phil Gard, remembers a fractious phone call around this time, during which he accused ‘Neil’ of being a cop and engineering the split in Class War. He wondered if this is the reason he never saw ‘Neil’ again.

HN122 denied ever being accused of being a police officer, and reverted to a line he used a few times, saying that Phil must have confused him with someone else. However he can’t think of anyone he might have been confused with, and doesn’t remember anyone else being accused of being a cop. He claims to have exfiltrated himself without raising suspicions, feigning gradual disinterest then telling comrades that he’d met a girl, and was going off to Wales to live in a commune.

He claimed throughout that he had no knowledge of the feedback or ‘briefs’ given to his managers by the Security Service, and says he only realised they were interested in Class War at the time of his post-deployment debrief with them.

Overall, HN122 claimed not to ‘recall’ lots of specific events, and gave vague, non-committal answers to the Inquiry’s questions. He maintained that he just did what he was told by managers

He was asked about overtime payments. HN122 recalled that there was a ‘cap’ on how many extra hours an SDS undercover could claim for each month (an average of 115) and as a result, he often worked more hours than he was paid for.

The day’s testimony ended with HN122 looking exhausted, having faced hours of questioning about his actions and their justification. His final responses remained as evasive as his first, leading Chairman Sir John Mitting to dismiss him just as he appeared ready to offer one last ‘I can’t recall’.

Those who sat through the day’s hearing described it as ‘dry and difficult’.

Thursday 24 October 2024

Evidence of Richard Adams

Click here for video, transcripts and written evidence

Richard Adams, 2018 (Photo: Teri Pengilley)

On Thursday morning we heard evidence from Richard Adams. He has supplied the Inquiry with a written Witness Statement. The family (he, his wife Audrey and son Nathan) contributed an Opening Statement as well

His two sons were attacked by a racist gang in 1991, resulting in the death of the older boy, Rolan, who was just 15 at the time.

Aphra Bruce-Jones, the Inquiry’s barrister, led Richard through his statement, starting with his memories of Rolan’s birth and boyhood, giving us a rounder picture of him and his interests. These included making music and playing football. He was close to Rolan; the two brothers were also close, just one year apart in age.

The family lived in Abbey Wood, next to Thamesmead. On the day of the attack, 21 February 1991, the boys went there, to play table tennis at the Hawksmoor Youth Club and collect some records. As they were waiting at the bus stop to catch a bus home, they were confronted by a group of aggressive white youths.

Nathan’s account of the incident was recounted. He remembers Rolan starting to run – and telling him to run too – whilst holding his neck. The brothers split up to evade the gang, and by the time Nathan saw Rolan again, he was lying on the ground. He had been stabbed in the neck.

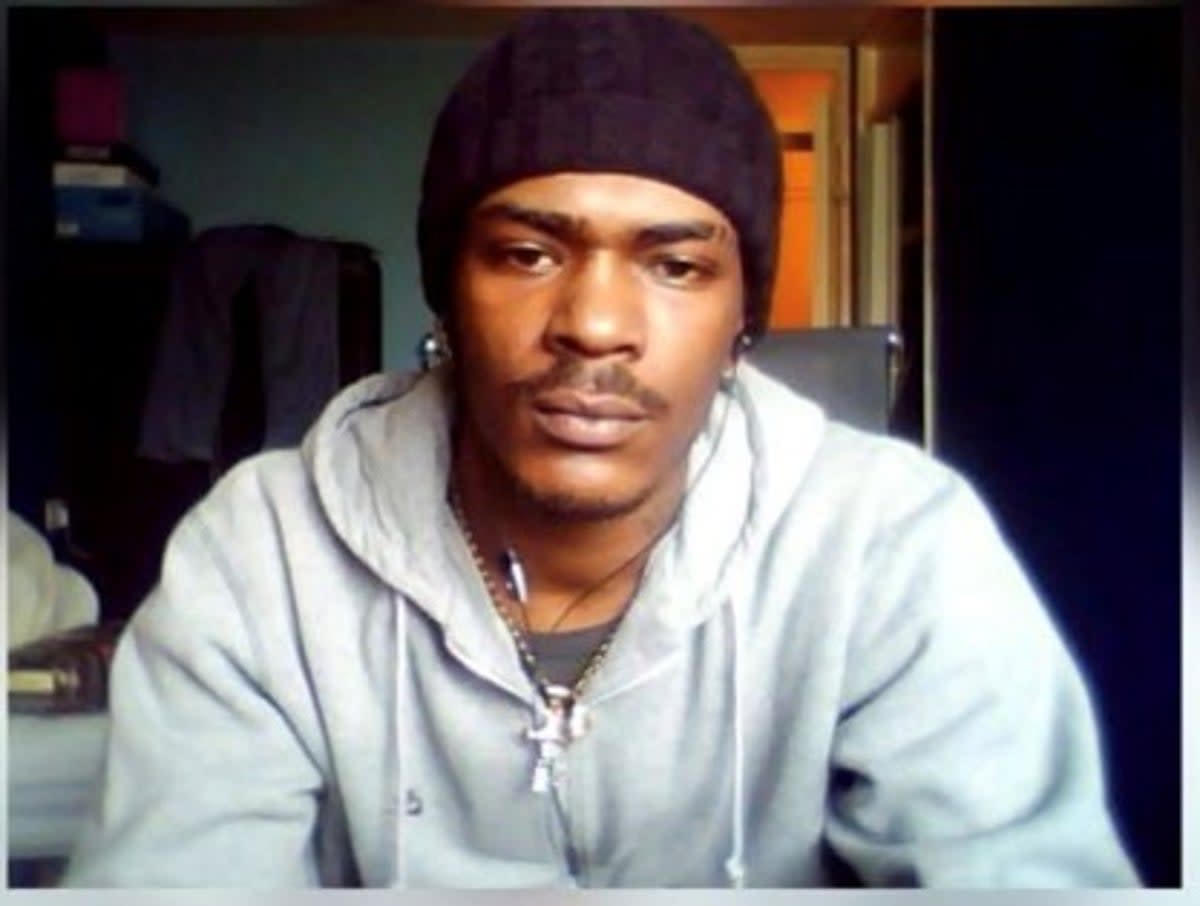

Rolan Adams

An ambulance arrived, and tried to treat Rolan, eventually taking both boys to hospital. Upon arrival, Rolan was taken off somewhere. Medics told Nathan that his brother had died of his injuries.

Instead of treating him sympathetically, or taking him home, the police who were present restrained him, put him in a headlock and hauled him to the police station. There he was questioned and swabs were taken. Despite being injured himself, and covered in his own and his brother’s blood at the time, they treated him as a suspect rather than as a victim.

The family soon learnt more about the youths responsible for Rolan’s murder. They were members of a gang, who called themselves the ‘Nazi Turn Outs’, KKK and/or Goldfish Gang, and were described as ‘something of a British National Party (BNP) youth movement’.

Rchard explained that this gang had caused problems for years, terrorising other Black families locally and carrying out a string of racist attacks. It wasn’t until Rolan’s death that the media took any interest. Richard said that if he’d known about the level of violence being endured by Black people in the area, he would never have moved his family there.

The racists congregated next to the Wildflower pub, close to the youth club. This pub was known as a meeting point for BNP members and a centre for drug dealing.

Nine people were arrested following this incident, but only one of them, Mark Thornborrow, was ever charged with murder. Four others were charged with violent disorder; nobody was charged with the attack on Nathan.

The police and Crown Prosecution Service refused to consider this a racist crime (despite the white boys saying ‘kill the nigger’ as they carried it out – Richard gave the Inquiry permission to quote their use of this word).

Richard says he is very grateful to the judge at that trial for ruling that it clearly was a racist murder, and for sentencing Thornborrow accordingly.

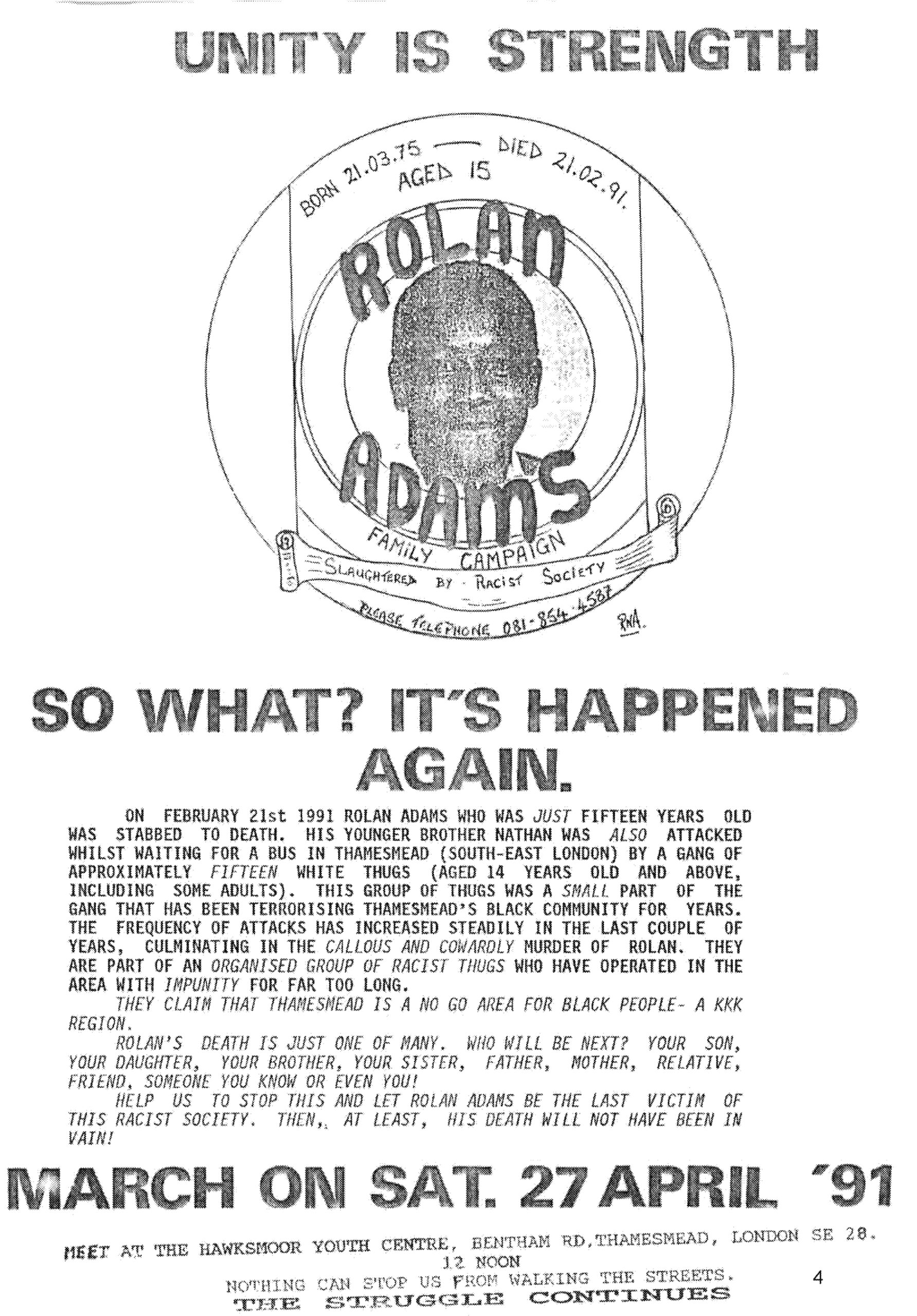

The family sought justice, set up a campaign, and organised a march on 27 April 1991. The flyer for this was exhibited.

Richard explained why this said Rolan had been ‘slaughtered by racist society’ – because they considered it a societal problem, of institutional racism, that the only person in authority who recognised this as a racist murder was that one judge.

‘We knew from the outset that, you know, we weren’t going to get justice’.

There was a youth worker at the Hawksmoor, Anne Brewster, who had become increasingly concerned about the rise in racist attacks, and gone to both Greenwich council and the local police to raise this. After Rolan’s death, the youth club was firebombed.

Rolan Adams campaign 1991 flyer

The family didn’t know who to trust. After Rolan’s death, they started receiving anonymous phone calls, day and night, some of which specifically threatened Nathan, who was in hospital at the time. Rihard told the police that if they didn’t provide any protection for Nathan he would organise this himself, and so the police finally sent one officer to the hospital.

As well as the arson attack on the youth club, wreaths laid by the family to mark the spot where Rolan fell were also burnt. As a result, they felt that they had to bury him outside of the borough, to avoid his grave being desecrated. They were well aware that the BNP knew where they lived, so were afraid of being the targets of more violence themselves.

In April 1991, just a few months after Rolan’s murder, while they were still deep in grief and trauma, his family were informed (by Ros Howells – now Baroness Howells – Mavis Clark and Noel Penstone, all connected to Greenwich council at the time) that they were in imminent danger. They moved out of their house that night.

The Rolan Adams Support Campaign, which later became the Rolan Adams Family Campaign (RAFC), was set up ‘to campaign on many fronts’.

According to the minutes of their inaugural meeting, they aimed to combat racist attacks and harassment. They planned to raise awareness, provide practical support and solidarity to other victims, and even help families who wanted to move out of the area.

Richard said:

‘We were there trying to use our grief and our pain to help others, you know. There’s nothing we could do for Rolan’

Those involved in the campaign were anxious to prevent any more children becoming victims of violence, or becoming perpetrators.

One of the issues they campaigned about was the BNP’s bookshop/ headquarters in Welling. Since it opened in 1989, there had been a noticeable rise in racist attacks in south east London. Another Black boy, Orville Blair, was stabbed to death in Thamesmead three months after Rolan. An Asian boy, Rohit Duggal, was similarly murdered in nearby Eltham a year later. They supported Rohit’s family, and later Stephen Lawrence’s family.

Richard stated that the family ‘had a clear agenda on what we wanted’. They would have ‘open and frank discussions’ with anyone who came along to their meetings, including members of Anti-Fascist Action, as minuted.

One of the spycops, HN90 ‘Mark Kerry’, mentioned the RAFC in a report in September 1991. He said they had called for a picket outside the court when Thornborrow’s trial began on 7 October, and this has been advertised in the pages of the Socialist Worker newspaper.

Richard was unconcerned about this. He explains that the family were on friendly terms with a number of Socialist Workers Party members, as individuals, adding that ‘some of the members are still a friend of mine now to this day, 30 years later’.

The Socialist Workers Party (SWP) had been extensively infiltrated by the Special Demonstration Squad for decades by this time, and any groups the SWP supported became suspect to the Squad.

We moved on to hear that Reverend Al Sharpton had also supported the family, and remained in contact ever since. Asked about the campaign’s attitude towards physical confrontations with fascists, Richard explained that they had a ‘mantra’ of non-violence:

‘Everything about the literature that we’ve ever put out and everything that we’ve ever believed in, it was about ensuring that our young Black men stayed out of trouble’.

Minutes from another RAFC meeting, in February 1992, mention the Anti Nazi League (ANL), a group that the Special Demonstration Squad had long targeted.

We heard more about how the ANL had been reinvigorated after Rolan’s murder, and swung into action to mobilise around RAFC, in particular their campaign to close down the BNP bookshop.

There were other organisations and networks that supported RAFC’s aims and demonstrations, including Anti Racist Action, and Richard explained again that he and his wife tended to form personal relationships with individual supporters, and that was more important to them than people’s party allegiances.

The Inquiry seemed very keen to understand their attitude towards ‘violence or physical confrontation’ at such demonstrations and kept asking Richard about this, forcing him to repeat what he’d said earlier.

‘We often felt that we were under some sort of surveillance’.

The family had suffered break-ins when nothing valuable was taken, something familiar to those whose campaigns are disliked by Special Branch.

They didn’t know whether it was the local police or some ‘special squad’, but were not surprised to learn years later that they had been the subject of SDS reports.

Richard says now:

‘we felt more vindicated to know that what we thought was true, was in fact true’

His son Nathan’s statement echoed this, saying:

‘he realised that he wasn’t paranoid after all’.

After the Inquiry had asked all their questions, the family’s barrister, Rajiv Menon KC, asked a few more.

Richard remembers the police sending a Family Liaison Officer, a PC Fisher, to their house. He only found out afterwards that Fisher was supposedly the local ‘Racial Incidents’ officer.

The family didn’t warm to him. He would turn up uninvited, without warning. He didn’t really support them:

‘there wasn’t any empathy or any genuine warmth or anything like that’.

Fisher tended to pump them for information about their visitors and campaigning. He kept telling them that suspects were being released on bail or their charges were being dropped.

Rather than the police using their resources to investigate racist crimes, they regularly stopped and searched friends and relatives on their way to visit the Adams family, including Richard’s brother. He recalls being angry about this, but also frightened – how did the police know which people were visiting him?

Richard went on to make some comments about how ‘effective policing’ might have prevented the deaths of his son and other sons. He wants to know who made the decisions about undercover policing and why the spycops were directed to spy on him, rather than on the BNP and other racist criminal groups. He believes ‘the wrong people were being policed’.

Richard wants this Inquiry to provide answers to the questions he and his wife have been asking for years, and believes the public needs these answers too.

The Inquiry chair, Sir John Mitting, appeared again after this, and repeated what he said last week – that he intends to investigate these matters in ‘closed’ hearings, and it is likely that any resulting report will also be ‘closed’ (i.e. kept secret). He warned Richard plainly:

‘you may not learn the outcome’.

Evidence of John Burke-Monerville

Click here for video, transcripts and written evidence

John Burke-Monerville (back) with family members, 2017. (Photo: Linda Nylind)

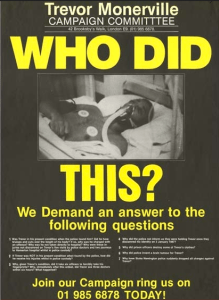

John Burke-Monerville came to talk about the Trevor Monerville Defence Campaign, set up to pursue justice for his son. He has also made a written statement.

His wife Linda sat beside him while he gave evidence:

‘She asked me this morning could she be near me to cuddle me if I break down.’

He placed a photograph of Trevor in front of him while he spoke, although he explained that he personally has no photographs of Trevor:

‘I find it too painful looking at him day after day. So I keep no photograph of him at all. I just want to remember him the last time I saw him alive.’

Now in his eighties, John gave powerful testimony and showed more dignity and humanity in a few minutes than we have seen in the countless hours of evidence from all the undercover officers combined.

Trevor was born in 1967. John struggled to remember Trevor’s birthday, but he remembered the day he died, 18 March 1994. He was 26 years old.

Trevor was injured when he was 19 years old. An active young man in good health, he was out with two aunts on New Year’s Eve 1986-87. They went into a club and Trevor waited outside, and when they came out, they couldn’t find him.

The family was unable to track Trevor down until Sunday 4 January:

‘The first thing I did [on 1 January] was I walked into Stoke Newington Police Station, and asked them if they had Trevor in custody. And they said they did not have him.’

On 2 January 1987, John filed a missing persons report with Stoke Newington Police.

‘I went to the police station to make enquiries again with a photograph of Trevor… They still maintained they did not have him in custody… We had members of the family phoning hospitals…

‘I was told that he’s a 19-year-old by the custody officer, maybe he has scored for the night. That is what I was told.’

They finally found Trevor in Brixton Prison. He was incoherent and had soiled himself. He was covered in bruises and congealed blood. His left eye was black and puffed up. His right eye was in an abnormally fixed position. His mouth was slack and open, and the inside was swollen.

‘It turned out to be Trevor. I was shocked. Truly, truly, truly shocked. The only thing I could say to him, “Boy you got a good body on you, hold on in here I’ll be back” and he asked me “Why dad? Why did they arrest me?”

‘I went back to Stoke Newington Police Station and asked questions about Trevor… they realised that I’d found Trevor, and they had him in the prison’

The custody record shows Trevor was arrested at 22:40 that night, having been found unconscious in somebody’s car. It records him continuously sleeping, incapable of being aroused, refusing food. He wasn’t provided with legal representation.

Trevor Monerville

He was seen by three different police medics, on five separate occasions. He suffered a number of seizures whilst in police custody, and had been taken to Homerton Hospital twice. The Accident and Emergency department doctor advised he just needed to sleep off whatever it was.

He was charged with criminal damage on the evening of 2 January. Six police officers restrained him to take his fingerprints by force. Within two hours of the fingerprints being taken and Trevor being found ‘fit to be detained’, he was again admitted to hospital.

On 3 January he was produced at the magistrates’ court, but wasn’t well enough to be physically brought into the courtroom. The judge remanded him to Brixton prison anyway.

When his father was able to visit he kept saying ‘Why did they arrest me, dad? why did they arrest me, the bastards’.

Soon after that he was rushed to the Maudsley hospital with a suspected brain injury. There was a police officer at the hospital, guarding his bed, but eventually he informed the family that charges had been dropped and they were able to see Trevor.

He had a fracture to the right temporal lobe and a haemorrhage, and swelling to the right side of his brain. He had to undergo emergency brain surgery. He was in hospital for around three weeks.

Doctors informed the family’s solicitors that Trevor had a degree of brain damage, skull fracture, injuries to the left eye, nose, elbows, knees and shins; such multiple injuries was inconsistent with a fall. A medical report was later prepared by a neurosurgeon. Trevor sustained an intracranial clot caused by assault. Blows to the head. Not a fall.

Trevor was unable to take care of himself when he left the hospital.

‘He wasn’t be able to talk properly. He wasn’t even interested in going to the loo. All these things I had to teach him to do them again… Feeding him was like a baby, feeding a baby… he could walk but on a side with his head bend on the side…

‘his questions to me was, why did they arrest him, why did they beat him up, why did they assault him…

‘I do not know who arrest him. I ask for the arresting officer’s detail, but nobody gave me anything.’

The police went on to claim that Trevor’s behaviour and his comatose state was due to drink and drugs. It was insinuated that he must have had some sort of pre-existing brain condition or brain tumour.

‘there was absolutely nothing wrong with Trevor… It made me believe that Trevor had an encounter with the police at the time and they were lying about everything to us…

‘the thing is that that particular station has been a very notorious place for a long time… my suspicion was that something was wrong and I wasn’t being told the truth’

After those events, Trevor became the subject of continuous stops by the police. He was arrested five times in less than two years, while he was still suffering the after-effects of the surgery, including epileptic fits.

In November 1987, he was arrested and charged with 11 offences, all of which were either not pursued, dismissed at court or found not guilty. In 1988 the police apologised for yet another wrongful arrest.

‘It was constant harassment… these sort of things were very painful to cause a boy at this time after his operation. He wasn’t functioning properly then…

‘I believe the prognosis of the doctor they were frightened of it… they were sure that Trevor would get his old memory back and he will be able to say everything that happened to him… whoever it is that caused Trevor’s injuries was pretty worried.’

Trevor was sent to stay with family in St Lucia.

‘I cannot remember exactly how long he spent there, but that was his happiest time… as soon as he got back here it all started again… it resume itself just as ugly as before.’

The Trevor Monerville Defence Campaign

John instructed solicitors to liaise with the authorities. Legal action was taken on Trevor’s behalf against the City and Hackney Area Health Authority, the Metropolitan Police and the Home Office.

John instructed solicitors to liaise with the authorities. Legal action was taken on Trevor’s behalf against the City and Hackney Area Health Authority, the Metropolitan Police and the Home Office.

The family ran the campaign. The aims were to learn the truth about what happened to Trevor, how he got his injuries, why he didn’t receive proper medical assistance, why he got no legal assistance whilst in custody, and whether the police were covering anything up.

There was also a wider aim to expose racist policing in Stoke Newington and Hackney, and provide support to other campaigns for Black youths who had been either hurt or killed while in police custody.

Two of John’s sisters, Annette and Cassie, were significantly involved in the campaign, along with Dr Graham Smith, who Inquiry counsel described as ‘a prominent civil rights activist in the area’.

John corrected him there:

‘I wouldn’t say he was a civil activist – but he was a very nice person, who wanted to help those suffering.’

The campaign made a number of public appeals and organised demonstrations outside Hackney Police Station, Dalston Police Station and Stoke Newington Police Station. Always peaceful. Nevertheless, the Inquiry asked John three times whether the campaign was ever disorderly or violent.

The campaign attracted significant wider support, including interest from Tommy Sheppard, member of the Hackney London Borough Council and chair of the council police committee at the time.

Sheppard spoke to the press and publicly questioned the behaviour and accountability of the local police. MPs such as Diane Abbott, Paul Boateng, Bernie Grant all lent their support to the campaign. Ken Livingstone raised the question in Parliament in April 1988.

The MP for Hackney South and Shoreditch, Brian Sedgemore, wrote to the then Commissioner of the Met, Sir Kenneth Newman and to the Home Secretary, Douglas Hurd, from whom John received a strange reply:

‘I had a very strange letter from Douglas Hurd, paying me condolences for Trevor’s death while he was still alive… but like everything else that was at the back of my vehicle, the letter disappear…’

Counsel asked whether the theft was reported to the police. John replied ‘what for, sir?’

He clearly believes it was the police who broke into his car, and he may well be right. They were certainly spying on the campaign.

We were shown posters and fliers from the campaign, which included a graphic photograph there of Trevor taken at the time.

John commented:

‘We did break the law there because we sneaked into the hospital with a camera and took that picture.’

The Inquiry reassured him, ‘you may have broken the rules but I’m not sure you’ve broken the law.’

‘All these years I thought that we broke the law,’ John replied.

The campaign received a public apology from the officer in charge of Stoke Newington police station.

‘He apologised for not telling us, well telling me and the rest of my family and the crowd that was supporting us at the time that Trevor was in their custody. So he’s sorry for not letting us know.’

However no satisfactory explanation as to how Trevor sustained his injuries was ever given. Whilst the Campaign was active, the family was treated very badly by the police. The police arrested John’s parents.

‘My mother was treated very badly… my father was 79. And my mother was 73.’ No charges were brought.’

The campaign was wound down while Trevor was in St Lucia.

Bak in London, Trevor was stabbed in the street and killed on 18 March 1994. The police did nothing at all. The inquest into Trevor’s death concluded on 13 March 1996. The family wasn’t informed.

Spycops spying on the campaign

At this point in the hearing, the Inquiry began to exhibit intelligence reports filed by the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS).

In February 1996, the police were filing secret reports about a demonstration for Trevor due to take place three days after the inquest, yet they failed to notify the family that an inquest was taking place.

The police claimed:

‘The original FLO [Family Liaison Officer] was apparently unable to contact Trevor’s father prior to Inquest.’

John still lived in Hackney at the time.

A police report closing the investigation into Trevor’s murder was dated 2 March 1995. It was not made available to John until September 2023.

Asked how he felt that it took 28 years for him to learn of the report into Trevor’s murder, John replied:

‘I couldn’t answer that, sir, because the anger that bring on, it would take angry language to discuss that.’

The Inquiry then showed suggestions from the time, made by Stoke Newington police, that the Trevor Monerville Defence Campaign was being manipulated by political agitators. That was untrue.

John explained that the campaign did receive support from other groups.

‘I suppose [some of those groups] wanted to try and manipulate us… then they had to take a walk and all.’

Nevertheless, this suggestion that the group was being manipulated was revived by the Metropolitan Police to try to justify SDS reporting on the campaign. The extent and nature of the reporting we were shown totally undermines that claim.

SDS officer HN95 Stefan Scutt ‘Stefan Wesolowski’, who infiltrated the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) in Hackney South between 1985 and 1988, reported:

‘The parents of Trevor Monerville are understandably still extremely distressed… They will seek public support only in pursuing their objective, for example an independent inquiry’

His report indicated that the Trevor Monerville campaign had Special Branch ‘Mentions’, ie previous reports by other officers had mentioned them.

On 9 September 1988, HN10 Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’ also reported on the Hackney Community Defence Association, who supported the campaign, describing it as a ‘front organisation’.

John said of Bob Lambert

‘He’s the greatest liar I’ve ever heard speak.’

On 13 December 1988, HN25 ‘Kevin Douglas’ filed a report concerning the Broadwater Farm Defence Campaign and a picket that was held at Wormwood Scrubs Prison, noting chants at the picket in support of the Trevor Monerville Defence Campaign as well as other causes.

A report dated 13 February 1996, attributed to HN15 Mark Jenner ‘Mark Cassidy’, notes an event to mark the death of Trevor Monerville, who he describes as

‘A black man who died allegedly as a result of his treatment at the hands of Stoke Newington police.’

Counsel to the Inquiry questioned the claim that Trevor died as a result of his treatment at the hands of Stoke Newington police, but John set him straight:

‘It is quite right. That is my belief. And I can’t see any other way but that. If they didn’t do it their self… in my mind they had something not quite right to do with it.’

By February 1996 it is clear that the Trevor Monerville Campaign had its own Special Branch Registry File, number 400/87/146.

We also heard how HN15 Mark Jenner ‘Mark Cassidy’ infiltrated a meeting held by the family on the first anniversary of Trevor’s death, and how whistleblower SDS officer HN43 Peter Francis subsequently told John that he was also on the campaign before being sent over to the Stephen Lawrence campaign.

SDS interest in the Trevor Monerville Defence Campaign was extensive and spanned at least five different undercover officers, and at least eight years.

Notes from a meeting between Operation Herne and HN2 Andrew Coles ‘Andy Davey’, who infiltrated the animal rights movement, record him commenting:

‘I know about Trevor Monerville.’

John’s frustration at this was clear.

‘All these people know about Trevor Monerville, but no one is telling the truth about what they know. What does he know about Trevor Monerville? He should have the decency of letting me know what he knows about my son. He must know as a father that I would love to hear what he knows about my son… Because I am in the dark.’

On 26 August 2014 Operation Herne contacted the family about the spying and they later received an apology.

‘The Metropolitan Police Service fully accept that a significant amount of information was incorrectly gathered, recorded and retained as a direct result of the way in which the Special Demonstration Squad operated…

‘we fell so far short of our responsibility to properly handle information.’

However, Operation Herne told the family very little documentary information had been found, just one document, two or three lines. That was untrue.

In fact, as early as 1987 the SDS Annual Report included the Trevor Monerville Defence Campaign in a list of organisations directly penetrated, or closely monitored, during the year (redacted by the Inquiry in the report, they nonethelss confirmed it in the hearing).

John is being forced to relive the horrific memories of his son’s brutalisation now because undercover police deliberately targeted his family for seeking answers and justice in respect of police violence, racism and corruption.

Nevertheless, John explained:

‘I do not have any mis-feelings about police. I believe in law and order. When I was a young man when I first arrive in this country my initial thoughts was to join the police force and become something in it and then rush back to Saint Lucia and become a big boy…

‘I was told I was too short. And when I was told that they are recruiting at my height… I couldn’t live on the police cadet wages…

‘I do regret it. But I had two sons to take care of. I have no ill feelings about the police. But I do not enjoy what they practise.’

The understatement of those words.

Joseph Burke-Monerville

We were told how John had other sons: twins, Joseph and Jonathan were born just six months before Trevor died. Educated in Nigeria, they returned to London just before they turned 19.

On 16 February 2013, Joseph and Jonathan were with another brother, David, at a gym in Hackney. They were approached by two men and shot at, in a case of what the police later concluded to be mistaken identity. All three boys were injured. Joseph was shot in the head and died.

At this point John left the room for a moment to be with his wife.

In fact, John has had to engage with the Metropolitan Police in tragic circumstances involving three of his children. His son David was killed in a violent robbery in 2019. Only David’s killer was ever brought to justice.

Three men were charged in connection with Joseph’s killing but the prosecution didn’t proceed. At that time, the Family Liaison Officer brought up Trevor’s name, telling John that Trevor was a strong boy; that it took six officers to restrain him, and asking to be provided with a Monerville family tree.

The pain of all this was evident throughout the testimony.

John told us:

‘When you are done with me and things have quietened down a bit that I have to go and rest my head for three reasons: my son Trevor, my son Joseph, and my son David. I have not left this country for the last 14 years and yet they couldn’t find me…

‘The last time I was away was 2010… all of Trevor’s jewellery that he always wear, including his clothes, phone, jacket, never got any of it back’

We were left in no doubt about the root causes of so much grief. Charlotte Kilroy read aloud from John’s written statement:

‘The behaviour of the police towards Trevor, me and my family since he sustained his life changing injuries – the failure to look for him when I reported him missing, to tell me he was at the police station or to investigate what happened to him, the harassment of Trevor and my family afterwards, the spying on my campaign, the exposure of racism in the Metropolitan Police Service then and since – it all supports our view that Trevor was assaulted by the police and that we were spied on because of our campaign to expose that.’

He added to that in his oral evidence:

‘At the end of everything that has been said, I truly believe racism by the police force and those in authority that control the police are to blame… They are to blame for not investigating properly… police is responsible for the beginning of Trevor’s trouble and it leads up to his death… we do not believe that we will ever get satisfaction. But we are still hoping for a surprise.’

He concluded his evidence by saying:

‘I don’t think you have gone far enough with me because there are many things in my heart I would like to get off my chest…I thank everybody for coming and sitting patiently to listen to me. Thank you all. On behalf of myself, my wife and my family. Thank you.’

Finally the Chair, Sir John Mitting, closed the session with these words:

‘Mr and Mrs Burke-Monerville, may I thank you sincerely for performing the very difficult task of giving evidence about matters that no family should ever suffer in peacetime…

‘Everybody who has listened to your evidence – I speak I am sure for everybody – has been deeply impressed by the calmness and dignity with which you have given it. Thank you for performing a serious and valuable public service.’

For once, Mitting actually got it right.