UCPI Daily Report, 19 May 2022

Tranche 1, Phase 3, Day 9

19 May 2022

Witness:Angus McIntosh (officer HN244)

The penultimate day of the 2022 Undercover Policing Inquiry hearings, dealing with spycops’ managers 1968-82.

Today, we first heard about Richard Walker (officer HN368), who worked in the SDS back office for over three years. He was not called to give oral evidence, but provided the Inquiry with a witness statement, so a summary of this was read out by a member of the Inquiry team.

The Inquiry then introduced documents relating to Lesley Willingale (officer HN1668), who is now deceased.

Only one witness gave evidence at the hearing: Angus Bryan McIntosh (officer HN244), the Detective Inspector who served as second in command of the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) from mid 1976 to late 1979.

Lacking the polished veneer of his colleague Geoffrey Craft (officer HN34) the previous day, Angus McIntosh (inadvertently) gave more insight into the attitudes of the unit towards those it was targeting. A number of his statements caused outrage.

Otherwise, what we encountered was not dissimilar to much of the other live evidence so far. A mixture of truth and dissembling; though more forthcoming than others, he also had inexplicable memory lapses on important issues.

He was a teenager when he joined the police, moved to Special Branch in 1964, and continued to be promoted, up to Commander level – moving to National Coordinator of Ports Policing when it was formed in 1987, and staying in this role until he retired from 11 years later – very much a career Branch man.

TRAINING

Rebekah Hummerstone

Rebekah Hummerstone, barrister for the Inquiry, began by questioning him about his understanding of the law around policing.

McIntosh recalled attending police training courses at Bramshill and Hendon during this time, but these were general, and didn’t cover anything to do with undercover policing.

He was asked how he understood police powers to apply to undercover work, and admitted that they hadn’t given much thought to this at the time.

He suggested that if officers were invited to enter a private home or premises – even if this was under false pretences – they did not need a warrant, and suggested that in fact, not accepting an invitation might raise suspicions and therefore jeopardise their cover story.

He says his role entailed him applying his common sense and instinct – it was about “careful people management” of the individual officers to ensure their morale and safety.

His Special Branch background provided useful knowledge of the groups being targeted, the style in which reports were created, and some of the possible pitfalls. However the unit’s tactics were new to him, and he says there was no manual, and no specific SDS training course in those days.

In his statement he says that he introduced tutoring for SDS officers so they could take their ‘promotions exams’, and felt that his role included providing informal training for them, including the new recruits, who joined the office team first.

He says that he just learnt on the job, as was standard practice in those days, and adopted the unit’s existing practices.

CRAFT WORK?

Yesterday’s witness, Geoff Craft, couldn’t remember working with McIntosh in the SDS. Bizarrely, today McIntosh could not recall working with Craft either. The Inquiry’s Chair, Sir John Mitting, has asked both men to explain why, as the timeline prepared by the Inquiry shows significant overlap.

McIntosh’s only theory to explain this confusion is that he knows that he was away on various training courses for months, during which time someone else – probably Lesley Willingale (officer HN1668) – would have been acting up to cover his Inspector role.

MIKE FERGUSON

Anti-Apartheid Movement demo, London, 1973

He did remember Mike Ferguson (officer HN135). He says that he first learnt the details of what the SDS (or ‘Hairies’ as they were known within the Branch) did from Mike, before he joined the unit himself.

He actually recalled an incident that took place during Ferguson’s undercover deployment, in which he infiltrated the Anti-Apartheid Movement.

Ferguson turned up one day at McIntosh’s home, ‘seeking refuge’ – his wife didn’t recognise him but Angus recognised his voice and let him in.

“He visited my flat in his undercover appearance and clothing before I was part of the SDS. He wanted to be in a safe place and took refuge in my flat. I do not know what it was that he was seeking refuge from, but he wanted to be off the street.”

Later on, when they worked together – Ferguson became Chief Inspector of the unit in early 1978, so was effectively McIntosh’s boss – he remembers them as close, Ferguson as able to give practical advice to the officers, based on his own personal experience of going undercover, and seems to have shared a lot of his knowledge with McIntosh.

THE BLACK FOLDER

Despite saying “there was no training manual”, McIntosh clearly remembered the ‘black loose-leaf folder’ that others have mentioned, which contained SDS tradecraft and knowledge that had built up over the years.

He described it as “full of good advice for the new officers”, but at the same time claimed that he never looked inside himself. Unfortunately, this contradiction was not picked up on.

He was asked if managers ever checked the contents, to ensure that suggestions of bad practice were removed, but seemed to think this wasn’t needed.

TASKING AND SUPERVISION

McIntosh would expect requests for information – including those from the Security Service – to come in via a Special Branch Squad, usually C Squad which dealt with left-wing activism.

The SDS managers met daily with their line manager, an S Squad Superintendent, and such requests could be discussed then. Sometimes they turned them down, if they didn’t have a source in a suitable place.

Referring to A8 (the uniformed public order unit) McIntosh said:

“We fed them; they didn’t feed us”

That is, although the SDS provided them with plenty of information, they didn’t receive any requests from them.

Sometimes this information was delivered via a phone call, especially when it was urgent news about an upcoming demo.

The unit’s managers had a lot of autonomy and made a lot of important decisions without any external input. They would keep the S Squad Superintendent informed, but not always give them all the details. They wouldn’t necessarily report any problems that arose.

NO SPYING ON THE FAR RIGHT

National Front demonstration

McIntosh said he was too junior to have been party to a “high-level policy decision” like the one not to infiltrate the far right. However he recalls that it was thought it would be too difficult and dangerous for an undercover to be sent in, as these groups were so very violent, and prone to criminality.

This is another glaring contradiction. Ever since the spycops scandal broke in 2010, the police have denfended it by saying they had to infltrate groups in case they were planning anything violent or criminal. But McIntosh says it wasn’t safe to infiltrate groups who were violent or criminal, so they focused their attentions elsewhere.

He then added that the police didn’t need to spy on the far right to keep an eye on them; they could obtain good information about them from the left-wing groups who monitored fascist activity, with much less risk to officers.

This is something we learned at one of last year’s hearings. Several spycops said that, despite the far right waging campaigns of violence and murder, they weren’t regarded as much of a problem. Only one SDS officer infiltrated the far right in the 1970s, and he did so inadvertently.

‘Peter Collins‘ (officer HN303, 1973-77) infiltrated the Workers Revolutionary Party who, in turn, sent him in to spy on the fascist National Front.

THE SECURITY SERVICE

McIntosh suggested that his lowly position as a Detective Inspector meant that he had very little contact with the Security Service (aka MI5).

However, this is somewhat contradicted by a document he was shown; a summary of the contact that took place between the Security Service and the SDS in 1979.

It shows that he and Ferguson attended a meeting in February on behalf of the SDS, and the Security Service were keen for these meetings to become regular monthly events.

HOME LIVES

It was considered essential for undercovers to have stability, an ‘anchor’, and so almost all of them were married men. McIntosh made a point of always visiting the partners of new recruits before deployment. He said the main reason for this was to introduce himself, gain her trust, and ensure she had a way of contacting him if she had any problems. He says hardly anyone ever rang the telephone number they were supplied with.

He would use this opportunity to tell the officer’s partner what to expect: long absences, working evenings and weekends, etc. Although they wanted to asses the officer’s domestic situation, they “certainly didn’t investigate”.

It was left to the officer to ‘use his judgement’ about how to explain his changed appearance and new job to his spouse: “rightly or wrongly, we left it to them to deal with it”.

The welfare of these women was of very little concern to the managers of the SDS, the only thing that mattered to them was maintaining the secrecy around these operations.

He also referred to the wives and families in the context of overtime, saying he was concerned that officers weren’t spending enough time at home, at the same time claiming the long hours of overtime were important for maintaining their cover stories.

STEALING IDENTITIES OF DEAD CHILDREN

McIntosh was asked about spycops’ theft of dead children’s identities to create undercover backstories or ‘legends’.

He seems genuinely aggrieved by this – not regretting the practice as such, but the fact that it was exposed by activists:

“I think it is most unfortunate that this Inquiry has enabled the poor families and relatives to realise that this has happened. In normal circumstances, it wouldn’t have happened. I mean, it’s extraordinary.”

WELFARE

Undercovers were expected to phone the office before 11am every day to ‘check in’. The meetings at the SDS safehouse also served a social purpose – as we’ve heard before, they offered an opportunity for the officers to relax together and be themselves. One of them would cook lunch, but the office staff did not join the undercovers at the pub.

We have heard about a dysfunctional drinking culture within the SDS. McIntosh was asked of the officers were given any guidance on drinking; he says no beyond no drink-driving.

SEXUAL RELATIONSHIPS

Again, as previously, the Inquiry spend considerable time on officers deceiving women they spied on into sexual relationships, as McIntosh oversaw a number of undercovers who did this.

The Inquiry asked about the comments of ‘Graham Coates‘ (officer HN304) about the sexist banter at the meetings. McIntosh remembers the banter but does not recall jokes about Rick Clark’s sexual prowess (see below). He says he was out of earshot most of the time, having individual talks in the other room.

Like Richard Walker (officer HN368), another manager who has given a written statement, McIntosh says that what banter he heard, he did not take particularly seriously.

McIntosh felt he was able to build close relationships with the undercovers and that they could have approached him for help with problems, but if these problems were what he called “self-induced” he suspects they may not have been entirely honest with him as a senior officer. Particularly, he couldn’t see any of them confiding in him about a relationship in the field as this could have affected their career.

Asked if Ferguson was someone they felt they could confide in, he said yes, “he was a man’s man.”

McIntosh was also agreed that the risk of relationships was a real one and meant a serious a security risk to the unit. However, he did not view it as a case of an officer abusing his power; in his view “things happen” and it was a personal, individual matter, security risks aside.

SPECIFIC OFFICERS

The Inquiry then asked McIntosh about a number of officers whose problematic behaviour has been frequently discussed at the hearings.

Vince Harvey (aka ‘Vince Miller’, officer HN354, 1976 -1979)

SDS officer ‘Vince Miller’ while undercover

When joining the SDS, Harvey had been in a long term relationship, but that had ended. McIntosh was not aware of that fact, but would have dealt with it as a matter of welfare.

McIntosh said he was “amazed” at learning of Harvey’s sexual relationships while undercover, which had only come to his attention through the Inquiry.

Had he known, he says he would have taken this to Superintendent level and expects that Harvey would have been withdrawn.

Richard Clark (aka ‘Rick Gibson’, officer HN297, 1974-76)

Clark was exposed after the group he infiltrated investigated him and confronted him with his stolen identity. He also had multiple sexual relationships while undercover, which contributed to this exposure. McIntosh recalls Clark being withdrawn from the field, but claimed not to know many of the details.

However he says he was part of the surveillance team who sat outside the pub while Clark was being confronted by his suspicious comrades, just in case things turned nasty for the officer. He thought that Craft was there with him; yesterday Craft testified that he was there, but with Superintendent Derek Kneale (officer HN819).

McIntosh’s vague memory is incredible, given the severity the threat this represented to the secrecy of the entire unit.

This officer’s compromise doesn’t seem to have prompted any particular evaluation around security and processes. New officers were trained in exactly the same way as Clark, complete with the stolen identity that could lead suspicious comrades to a damning death certificate.

He described Clark as “very outgoing… the type that would brag about anything.”

He said he’d had no idea about Clark getting involved with at least four women while undercover, and sounded quite upset about Clark’s conduct:

“His behaviour has let everyone down.”

Not because of the possible impact on the women though but, extraordinarily, blaming Clark for everything, including this Inquiry being set up and a spotlight being shone into the workings of the SDS.

He sounded genuinely distressed that things had ‘unravelled’ and the unit was no longer a secret, saying:

“One of the proud things of SB was that the SDS was run without the general knowledge of the Branch let alone the police force or anyone else. Now the whole thing’s been exposed, unravelled, and that’s why I think it’s a great shame.”

‘Jim Pickford‘ (officer HN300, 1974-77)

McIntosh described Pickford as a “strange character” but also claimed to be unaware of his reputation as a womaniser. Another officer has told the Inquiry that Pickford confided in him that he had “fallen in love with” a female activist, prompting him to go straight to one of the unit’s managers (in his words, “the one with a Scottish name”).

This led to Pickford being withdrawn from the field. McIntosh denies being this manager, and insists that he knew nothing, and just thought Pickford’s deployment came to its natural end.

He said that if he had known about this, he would have gone to more senior management, and Pickford would have had to leave the Branch (as this would have affected his vetting status). Craft also denied knowing about this situation at the time.

However, Sir John Mitting said that in the Inquiry’s ‘closed sessions’ where certain officers have given evidence without the public present, he heard very detailed and convincing testimony from an undercover about them telling management about Pickford.

McIntosh expressed surprise that Pickford’s subsequent marriage (to the same activist) saying it was “amazing that rumour control kept it a secret”. He again suggested that this might all have happened while he was away from the unit – perhaps Leslie Willingale had been the manager?

Perhaps conveniently for McIntosh, the Inquiry is unable to check this as Willingale is dead.

THE PRINCIPLE OF SEXUAL DECEPTION

McIntosh didn’t think officers had to be reminded that sexual conduct on the job was a breach of police regulations.

He said he never “probed”, or asked them if they were engaged in such activities it would have been pointless to do so as they were unlikely to tell him, their supervising officer, that they were breaking the rules.

He denied that such relationships equated to an abuse of position or power. He viewed this as “sexual contact between consenting adults”, not something he gave a “green light” to but only because it was against police regulations.

He was asked if he considered this to be deceit:

“I can’t really answer that”

Instead, he posed a counter-question:

“Does everyone say before they have a sexual encounter, what is your occupation? And if it’s a certain one, do they say ‘Definitely not, because you are a policeman, or postman?’ So no.”

Which, again, is starkly reminiscent of what his colleague Craft said yesterday, leaving a strong impression that the managers are coached as to what to say, or got together to straighten out their stories.

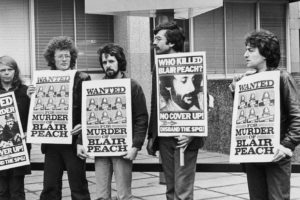

SPYING ON BLAIR PEACH’S FUNERAL

The Inquiry has heard that another former undercover was advised by his managers not to attend the April 1979 demonstration against the fascist National Front in Southall, because it was known that the uniformed police was going to ‘clamp down’ on the protesters.

McIntosh denied being that manager, or having any knowledge of this, but understood why the warning would have been passed on:

“Well, we don’t want our officers arrested. We don’t want our officers involved in violence.”

Despite him saying this warning represented a “fairly unusual statement” he was not pressed to explain the rather curious fact that, according to officer HN41, a decision had been taken beforehand to crackdown on the protesters.

Likewise, McIntosh could not remember that the SDS had arranged for an undercover to be smuggled into Scotland Yard to make statement about the death of Blair Peach. Chuckling, he replied:

“Not on this occasion, but we used to smuggle in officers for various reasons”

Again, he wasn’t asked to explain.

An undercover who was infiltrating the Anti-Nazi League, officer HN21, was tasked with attending Peach’s funeral. McIntosh says he can’t remember if it was him, or another manager, who gave this instruction.

McIntosh provided his justification for spying on the mourners, claiming it was necessary to “identify disorder” and normal to cover such events of interest:

“because the whole reason of the funeral was for a person involved in extreme left wing politics and demonstrations, that’s all.”

Even HN21 has said that there was no known risk of public disorder at this event. Faced with this, McIntosh dismissed his officer’s professional judgement as a “subjective one”.

Sir John Mitting then intervened, suggesting that:

“many people might think it distasteful for a police officer, whether undercover or not, to attend the funeral of someone who had died in the circumstances we now know and record the names of all of those capable of being identified who have attended it.”

Mitting’s choice of phrasing, ‘died in the circumstances we now know’, is very telling. Blair Peach was killed by police officers. The police investigation showed this at the time, and identified Inspector Alan Murray as being highly likely to have been the killer. Yet even now, Mitting seems incapable of describing it in this way.

At last year’s hearing on the anniversary of Peach’s death, the Inquiry held a minute’s silence. In his preamble, Mitting avoided all mention of the police, and merely referred to Peach being killed by ‘a blow to the head’. In doing this, he insults all victims of spycops and underlines his partisan nature that is draining the Inquiry of its potential to get to the truth.

The comments made by McIntosh in response were the most outrageous yet:

“I can understand some people being upset by it, but, however, in public disorder … I’m quoting Northern Ireland for instance, funerals are often a hotbed of problems, and it wasn’t the friends and relatives of the person whose funeral it was, it was because there was an opportunity of demonstration against… it would be anti-police, in one way or the other.”

It is an extraordinary rant, with the bizarre suggestion that the National Front might have demonstrated at the funeral.

“Unfortunately, sir, I don’t think there’s a lot of respect in those circumstances for the real reason of the occasion.”

He didn’t see the irony in his comments.

Blair Peach protest

Undercovers are known to have spied on the Blair Peach campaign at other events over the years. In one of last year’s hearings, we saw internal documents showing they were still spying on vigils for Peach on the 20th anniversary of his death.

In his written statement, McIntosh said that he did not believe they were reported on because they sought to discredit or criticise the police.

However, today he told the Inquiry something different, and was asked to clarify his views – why did he think those people had been reported on?

One of the excuses he gave was that if an undercover was sent to cover an event, they understood it was their duty to report the names of those present, without any filtering. It’s more likely that they would have included activists’ names on the list as the officers are more likely to have recognised those people.

He then claimed to not recall the full details about the demonstration where Blair Peach was killed. Which was maybe the first time ever that a police officer used those words, acknowledging what has actually happened.

Witness statement of Angus McIntosh

Transcript, video of the morning and afternoon the day’s hearing

The current round of Undercover Policing Inquiry hearings, focusing on Special Demonstration Squad managers 1968-82, continue until tomorrow, Friday 20 May.