UCPI Daily Report, 4 Feb 2026: Roger Geffen evidence

Tranche 3 Phase 2, Day 4

4 February 2026

Roger Geffen giving evidence to the Undercover Policing Inquiry, 4 February 2026

Roger Geffen gave evidence to the Undercover Policing Inquiry (UCPI) on the morning of Wednesday 4 February 2026.

Geffen is a long-standing environmental campaigner who was involved in the anti-roads movements and groups like Earth First! and Reclaim the Streets from their inception in the early 1990s, as well as more conventional campaigning for the rights of cyclists and sustainable transport.

His campaigning activities led to him being awarded an MBE for services to cycling. They also led to him being spied on by SDS officer HN14 Andrew James Boyling ‘Jim Sutton’, NPOIU officer EN12 Mark Kennedy ‘Mark Stone’, and probably other undercover officers over the past thirty years.

The UCPI is an independent, judge-led inquiry into undercover policing in England and Wales. Its main focus is the activity of two units who deployed long-term undercover officers (or ‘spycops’) into a variety of political groups: the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS, 1968-2008) and the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU, 1999-2011). Spycops from these units lived as activists for years at a time, spying on more than 1,000 groups.

INQUIRY CHAOS

The barrister acting for the Inquiry (known as the Counsel to the Inquiry) who questioned Geffen was Lennart Poulsen, who appeared to be very unprepared.

That is not entirely surprising as the Inquiry has gone ahead with these hearings when they have barely processed the evidence. In his Opening Statement to this phase of hearings, David Barr KC (lead Counsel to the Inquiry) noted:

‘Numerous and considerable challenges have led to the preparation of the T3P2 Hearing Bundle taking longer than planned.

We recognise that this has meant that documents have not been circulated to core participants as soon as we would have wished and that the process of circulating documents to core participants and publishing them on our website is taking place over an extended period.’

As is so often the case with public statements by the Inquiry about its work, this actually significantly understates the utter chaos surrounding disclosure, where much of the evidence has not yet been circulated to Core Participants preparing their evidence, and that has evidently also impacted on the ability of the Inquiry’s own barristers to prepare.

Geffen has produced a witness statement [UCPI0000038772] and he also contributed to the Reclaim the Streets (RTS) witness statement [UCPI0000038295]. Both were read into the evidence at the start of the hearing, and you can hear Geffen and other core participants involved in drafting the RTS witness statement talking about that process in episode 47 of the Spycops Info podcast:

Geffen’s evidence began with how he became involved in environmental activism. After leaving university he began working as a classical music record producer. He moved to South East London in the late 1980s and became a cyclist.

London traffic was wildly congested and dangerous at that time and he became involved in the London Cycling Campaign, and later a campaign against plans to build a road through Oxleas Wood, a piece of 8000-year-old ancient woodland close to where he lived.

‘This was an interesting time in environmental politics because the year after I got involved in London Cycling Campaign in 1989, was the year at that climate change really first came into public consciousness when the then Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, went to the United Nations Summit and declared that, as a scientist, she was convinced of the need to take action on climate change, but her government then announced what they called “the biggest road-building programme since the Romans”.’

Poulsen asks how Geffen became involved in direct action and he answers, explaining that he was influenced by Gandhi:

‘I’d seen the film Gandhi earlier in my teens and the idea was that there are times when you do need to break the law in order for justice to prevail.’

He also explains what direct action meant to him:

‘When the system of democracy and public input and all the rest of it breaks down… you just have to effectively take action directly… to highlight the problem to confront it directly and thus push for a resolution… you look to confront the root causes of the problem directly’

TWYFORD DOWN

One of the first schemes from the government’s 1989 road programme to start construction was the joining up of two sections of the M3 through Twyford Down, a heavily protected area of chalk downland just outside Winchester in southern England.

Protesters had set up a small camp on the route of the road, which Geffen visited in December 1992.

Twyford was a defining experience for Geffen. He began organising minibuses to take people from London to support the campaign and his first ever arrest occurred while taking action there.

He explains how that experience empowered him to take direct action:

‘I realised that the world hadn’t ended… and I felt proud of what I had done.’

He has seen very little reporting about the Twyford Down campaign, however he points out that the Inquiry’s disclosure of police documents indicates a Special Branch Registry File was opened on him in 1993, which coincided with his actions at Twyford Down and the early months of No M11 Link Road campaign.

Protesters occupy excavating machinery, Twyford Down, early 1990s

He points out that neither he nor anyone else involved in this Inquiry has received sight of those Special Branch Registry Files, and it is evident that there is more to be discovered about the extent of the spying than is apparent on the face of the disclosure he has seen.

Geffen therefore poses a number of questions for the Inquiry:

His name was on the Consulting Association’s ‘green list’ (an illegal employment blacklist of environmental campaigners). It is known that a private detective firm, Bray’s, was employed to spy on protesters at Twyford Down – filming and keeping files on those regularly taking part.

Geffen asks the Inquiry to consider what kind of collaboration existed between private companies like Bray’s or the Consulting Association and the Special Demonstration Squad at this time.

Geffen also points out that the Secretary of State applied for an injunction against a large number of activists, seeking to prevent them from trespassing on the worksite at Twyford Down. What role did the SDS play in that process? Or in the proposed civil action, suing protestors for damages, which should theoretically have followed on from the injunction but which the Government never pursued.

Here, Poulsen points out that six activists were jailed for breaking that injunction. Geffen agrees and talks us through the appeal of those injunction breakers against the length of their sentence:

‘It was before Lord Justice Hoffman and he came out with a wonderful quote … that really kind of solidified my own understanding of what I doing.

He talked about “the honourable tradition of civil disobedience in this country” and he added that “those who take part in it may well be vindicated by history”…

It wasn’t my words, but I think that very much crystallises the philosophy that led me to do what I was doing.’

Indeed, the road protesters of the 1990s certainly were vindicated by history. In Geffen’s words:

‘Twyford Down ended up being a noisy defeat for the direct action movement, and Oxleas Wood became one of the first of a large number of quiet victories.’

Two-thirds of the government’s proposed new roads were ultimately dropped, and it is clear that Geffen is still very proud of the role he played in those campaigns.

NO M11 LINK ROAD

After Twyford Down, Geffen and others’ campaigning focus shifted back to London, and the campaign against the M11 Link Road.

Geffen describes this as a ‘Cinderella project’ because unlike Twyford Down, Oxleas Wood, or the later Newbury Bypass, this was not a road that was set to destroy precious natural habitats. Instead it was being run through a residential community that had been purposefully run down by government compulsory purchase of the houses.

As such, the No M11 Link Road campaign moved the debate about road building on. Rather than just being about protecting the natural environment, it also became focused on the destruction of communities and the choices we make about the use of our urban space.

Geffen talks the Inquiry through a number of the actions and strategies that the campaign used, such as ‘Operation Roadblock’ and the squatting of Claremont Road.

Operation Roadblock was a plan to hold daily direct action on the worksites of the M11 Link Road, coordinating people coming from all over the country. Each day was preceded by a brief training session on the principles, practicalities and legal implications of non-violent direct action. This enabled and empowered people to make informed decisions about how far they were prepared to go to stop the diggers:

‘We were exhausted by the end.’

Claremont Road was the last fully intact street on the route. All the houses on the street had been compulsorily purchased, bar one.

Dolly Watson was 93 years old. She had been born in that street and she wanted to die there. One by one, protesters squatted the homes around her, creating a little self-contained car-free community, and she welcomed them into her road. Geffen explained:

‘Defending Claremont Road would be strategically crucial.’

With the homes being decorated and children playing in the street, it became a rolling street party that lasted for six months, and something of a prototype for the concept of Reclaim The Streets.

Claremont Road E11, occupied by anti-road protesters, mid 1990s

Poulsen was not very interested in the power of the community campaign, however, and instead pressed Geffen about any possibility of criminality, asking him about the times he was arrested.

Geffen very sensibly wrote his own statements about these arrests at the time, to support his defence. He has exhibited these to his statement to the Inquiry and is able to take Poulsen through the reasons why he considers them wrongful arrests. When charges were brought at all, he was found ‘not guilty’ over and over again.

A Special Branch report [MPS-0739546] describes one of the arrests, and Poulsen asks Geffen about the mood of the security guards on the day.

Geffen explains that some were very confrontational, while others were sympathetic and were just doing a job.

Protesters made friends with some of the security, but sadly it was the aggressive and confrontational guards who got promoted, so the make-up of the security team got worse over time.

Poulsen points out that the SDS report that ‘police conduct in the circumstances was restrained’. Asked if he agrees, Geffen’s short, dry, understated, ‘no’ was met with laughter from those in the public gallery who had been at present at the protests.

Geffen did a great deal of police liaison throughout the M11 campaign and says the police sergeant in question was quite honest in how he portrayed the campaign, in sharp contrast to the much of the SDS’s ‘intelligence’.

‘Q. Neither he nor other officers involved in the last phase of the M11 campaign tried to present you as anything but peaceful. Is that right?

A. Yes.

Q. And do you accept that those officers’ observations contrast with some of the SDS reports about you and the group’s actions?

A. Absolutely… and I think that would be a really good question to put to the SDS’s management. Why was it that they were so out to smear us, tarnish us with this label of being violent when we absolutely were not?’

Poulsen exhibited a flyer from the No M11 Link Road campaign, for an action on 22 January 1994. The image appeared on two dozen computer monitors all over the room, creating a beautiful juxtaposition between the raw energy of the campaigns Geffen was talking about and the sterility of the hearing room.

No M11 link road campaign leaflets, December 1993 and January 1994

However, Poulsen’s concern is that fliers like these might have encouraged ‘activists of a more militant and violent persuasion’ to get involved.

Geffen points out that things like that may or may not have been discussed at the time, but the key point is that it never happened.

The next exhibit was an iconic image of a banner action on the roof of the home of the then Transport Secretary, John MacGregor.

‘While we were out taking direct action on one of their work sites [the contractors] effectively came behind our backs and took the roof off one of the houses on Claremont Road…

We had this conversation where somebody kind of laughing said, “Oh, we should go and smash up the roof of John MacGregor”.

They weren’t serious, but you know it kind of prompted this idea that we should do that symbolically, by painting this banner that you can see there that effectively showed a road going through John MacGregor’s own home.

So, yeah, this was a piece of direct action that worked incredibly well in in media terms… peaceful direct action on the roof of the Transport Secretary on whose behalf bailiffs were smashing up other people’s homes um to really just highlight the injustice of what the Transport Secretary was doing.’

Poulsen asks how Geffen knew the address of John MacGregor and suggests that he was creating a security issue for the Transport Secretary’s family.

Geffen points out that the action was a peaceful protest that called attention to the very real violence being faced by the residents of communities affected by the M11 Link Road.

‘After all, cabinet level secretaries are expected to have a certain amount of thick skin and they’ve got the weight of the state behind them to protect them, whereas the residents of Claremont Road had nothing of the sort.’

Poulsen again tries to suggest the action was reckless:

‘What steps did you take to ensure no one would destroy his property?’

He suggests to Geffen that this action was ‘going too far’. However, again, Geffen simply points to what actually happened on the day. Although those arrested were charged with causing alarm, harassment and distress, they were found not guilty, because:

‘This had been an entirely peaceful protest that had been conducted safely, precautions had been taken, and this was again in that “honourable tradition of civil disobedience”, confronting the root cause of the problem in a peaceful way.’

Geffen also describes another similar protest against the Criminal Justice Act, which took place in the garden of the then Home Secretary, Michael Howard, noting that both actions attracted very positive media coverage, and stressing that:

‘Our networks were very solid on that common philosophy of believing in non-violent direct action.’

QUESTIONS ABOUT VIOLENCE

Twyford Down after the road was cut through it. (Pic: Jim Champion, used under GFDL and CC-By-SA-2.5)

Nevertheless, Poulson repeatedly presses Geffen on the question of violence, in between reprimanding him for giving overly complex answers to what are in fact very open questions about topics like the philosophy of direct action, attitudes towards breaking the law, violence and non-violence, and even whether activists ‘wasting’ the government’s road building budget had considered the affect that might have on the public purse.

Geffen points out in answer to this last question that, although additional policing and security was estimated to cost around £2m, they actually helped save the public purse around £18bn as a result of road building schemes being cancelled, not to mention the additional carbon emissions that were prevented as a result.

Poulsen asks a number of direct questions about ‘attitudes towards violence’ in Earth First! and Reclaim the Streets, and about Geffen’s own belief in the rule of law, before delivering what he appears to think is a ‘gotcha’ moment, saying that despite claiming to believe in the law, Geffen has supported people who have broken it.

Geffen is unfazed by these questions and simply explains again:

‘I believe that the rule of law is an important principle, but I also believe – and I do not believe there is a contradiction – that there are times when when the rule and the process of law and of public inquiries ultimately fails and that bad laws sometimes need to be broken.’

Poulsen continues to complain that Geffen’s answers are too long, and observers in the public gallery began to wonder whether the problem is that Poulsen lacks the attention to listen to long answers.

He is certainly doing the Inquiry no favours with this approach, and the overall impression is of a barrister tied to his list of questions, unable to adapt to thoughtful answers to what are obviously complex questions, instead just asking the same questions over and over again in different forms.

We are well into the questioning by this point, but Poulsen has not asked a single question about the undercover police infiltration of these groups or the behaviour of the spycops.

EARTH FIRST!

The Earth First! (EF!) network was very prominent at Twyford Down, where the focus was on the defence of beautiful landscapes and ancient woodlands.

As a group, EF! was infiltrated by a great number of undercover officers, including:

• HN2 Andy Coles, who claims to have been a ‘founder member’

• HN14 Jim Boyling

• HN3 ‘Jason Bishop’

• EN32/HN596 ‘Rod Richardson’

• EN12 Mark Kennedy

• EN1/HN519 ‘Marco Jacobs’

• EN34 ‘Lynn Watson’

EF! applied for Core Participant status in this Inquiry but it was refused, and the group has not been given disclosure in this Tranche. Poulsen nevertheless asks Geffen not only about his own role in EF! but also about the wider attitudes and actions of the network.

Geffen offers a short history of how Earth First! came to be launched in the UK and the close relationship with Reclaim the Streets, saying is was often the same people wearing different hats. He explains both groups were non-violent.

RECLAIM THE STREETS

Geffen first met with Reclaim the Streets (RTS) in 1992 when they were planning a sit-down protest on Waterloo Bridge in London. He attended this action, but didn’t feel confident enough to sit down in the road and face arrest.

There were a number of actions after that, including stunts at the Birmingham and London motor shows and painting cycle lanes onto roads in Lambeth where the council had neglected to do so.

Geffen explains the aims of some of these actions:

‘to highlight the problems of a society that is overdominated by dependence on motor vehicles and lacks sustainable transport alternatives to enable people to get around without depending on motor vehicles…

alternatives that would be better for our health, better for our air quality, better for our climate, better for social justice, better in so many ways, and yet the motor manufacturers sell us this dream that we all have to depend on our cars…

[while the way] the government spends its transport budget is contingent on perpetuating car culture rather than providing the alternatives.’

Geffen explains that Reclaim the Streets paused its activities in summer 1993 to focus on the No M11 Link Road campaign, but re-emerged in 1995.

At this point, Poulsen finally asks his first question about an undercover officer, establishing that Jim Boyling attended his first weekly meeting of Reclaim the Streets in November 1995.

Geffen rejects Boyling’s claim that these meetings were closed, and is very clear that they were open to anyone to attend. He suggests Boyling be questioned about this when the Inquiry brgins the spycop in for questioning.

During a break in the hearing, Tom Fowler made this reaction video:

In the early 1990s, the Metropolitan Police started deploying Forward Intelligence Teams, groups of officers with very high quality film and video camera who would document people attending political events.

We hear how Geffen was followed by members of the Met’s Forward Intelligence Team to his workplace. They then arrested him there on a dubious pretext, so they could offer him the opportunity to become a police informant.

A Metrpolitan Police Forward Intelligence Team, an intimidating presence at political events in the 1990s and 2000s. (Pic: Nicky Dracoulis, used under CC BY-SA 2.0)

This was shortly before Boyling began attending RTS meetings and Geffen suggests the Inquiry investigate the relationship between this failed attempt to recruit him as an informant and the decision to deploy Boyling into the group.

Geffen points out there were other police informants in the movement, and asks what the relationship was between them and the undercover police.

Geffen talks us through the tactics used by RTS, such as taking two old cars to be crashed into each other to block the street and make it safe for party-goers. RTS parties were incredible, vibrant, family-friendly events.

However, on a number of occasions they were attacked by riot police late in the day when people began to disperse. Poulsen incredibly asked Geffen whether he accepts that the police had a duty to ‘pick a fight’ with RTS in order to reopen the road.

Geffen disagrees, pointing to the nature of the events and the disproportionate levels of violence used by the police:

‘With hindsight, one of the things we learnt was that we should have made sure we had a plan for how how to end without allowing the police to do that.’

He adds that in fact that is exactly what RTS did at the next street party event on the M41.

Poulsen nevertheless asks (for the sixth time!) whether Reclaim the Streets street parties were violent or disorderly. He uses the fact that RTS would warn party-goers about the possibility of police violence or arrest, as though that somehow demonstrated that they were not themselves peaceful. It was incredibly frustrating to listen to, but each time these questions are asked, Geffen offered a sensible, detailed and patient response.

HN14 JIM BOYLING IN RECLAIM THE STREETS

It is remarkable how few questions Poulsen asked Geffen about the role of the undercover officer Jim Boyling who, using the name ‘Jim Sutton’, was tasked to spy on Reclaim the Streets.

Spycop Jim Boyling. Vans were commonly used by spycops as a way to make themselves useful to a group to the point of indispensability

Poulsen did refer to some of Boyling’s reporting and Geffen sets out in detail how inaccurate some of it was, highlighting ‘sexed up’ intelligence which pretended that RTS were attempting far more dangerous or disruptive actions than was in fact the case.

Geffen also points out how Boyling exaggerated disputes within RTS, noting that the spycops seemed obsessed with trying to drive wedges within the movement.

One example of this is a report claiming that Geffen was ‘excluded’ from a meeting about the Selar open cast coal mine.

Geffen says he has no recollection of this, but would have had no interest in attending that meeting if he had known about it, as he had no local knowledge to contribute to the discussion.

This is pattern also emerged in the evidence of ‘Monica’, with Boyling’s reports emphasising and exaggerating divisions within the group that the genuine people who were there simply do not recognise.

Boyling was far from unique among spycops. The Inquiry has seen that one spycop after another exaggerated the danger they were in, and exaggerated or simply invented the plans of the infiltrated group. These lies were further exaggerated by office staff who collated the reports, which in turn were exaggerated to an even greater degree by managers seeking to impress the Met’s top brass and the Home Office.

RTS IN LATER YEARS

Cover of spoof newspaprt Evading Standards, produced by Reclaim the Streets, April 1997

Asked about anti-capitalist activism in the late 1990s, Geffen explains how as time went on, Reclaim The Streets sought to widen the agenda from car culture to the fossil fuel economy and capitalism more generally.

It forged links between the environmental direct action movement and related workers’ struggles such as the striking Liverpool dockers, or London Underground workers campaigning against the privatisation of the tube.

However, Geffen stresses that he himself was not very involved in those later years. He points out that while he is grateful for the opportunity to give evidence, he feels that the Inquiry has failed to call the people who are best positioned to speak about that period when SDS spying on the group was at its most intense.

We do get to hear about yet another wrongful arrest though, when Geffen and two others received several thousand pounds in compensation after being arrested while preparing to distribute a spoof newspaper, the ‘Evading Standards’, on the eve of the March for Social Justice, shortly before the 1997 general election.

All 10,000 copies of the paper were seized and destroyed by police, and Geffen points out the seriousness of the police taking this kind of action simply to prevent a political group distributing its ideas.

‘It does look like another act of political policing – not the only one in Reclaim the Streets’ history – where the purpose of the arrest seems to have been to prevent us from getting our message out, rather than to prevent disorder.’

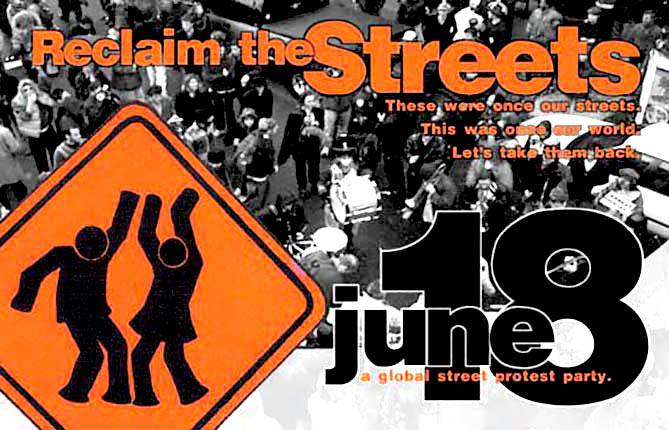

Poulsen seeks to ask Geffen about preparations for ‘J18’, the Carnival Against Capitalism in the City of London on June 18 1999, and Boyling’s role in it, including the purchase of several cars that were crashed to block the street. But Geffen again points out that he is not the correct witness to talk about this.

The Inquiry should be asking Jay Jordan, one of Geffen’s co-authors of the RTS witness statement to the Inquiry, who has important evidence to give about a number of issues.

Jordan worked on the production of the ‘Evading Standards’ newspaper, they were arrested and prosecuted alongside Boyling (who was using his false name ‘Jim Sutton’, even in court!) and they worked closely alongside Boyling throughout 1998 and 1999 on the planning of J18. It is hard to comprehend why Jordan has not been called to give evidence.

Nevertheless, we will undoubtedly hear more about SDS spying during those later years of RTS when questions are put to Boyling himself.

MARK KENNEDY AND CLIMATE CAMP

Mark Kennedy’s deployment will not be investigated until the Inquiry examines the SDS’s parallel unit, the National Public Order Intelligence Unit. These hearings, ‘Tranche 4’, have no date set but are not expected until the second half of 2027 at the earliest.

It is unusual for the Inquiry to question witnesses about other tranches. Nonetheless, Poulsen does ask some questions about Geffen’s role in the Climate Camp (or Camp for Climate Action, to give it its proper name), and his interactions with Kennedy there.

Geffen offers a potted history of the progression towards the Climate Camp, setting out how J18 influenced anti-capitalist movements targeting the summit meetings of global capitalist institutions like the International Monetary Fund, World Trade Organization and the G8, leading to the camp against the 2005 G8 meeting in Scotland.

Spycop Mark Kennedy with a bicycle D-lock round his neck locking him to the gates of Hartlepool nuclear power station, 29 August 2006

In turn, that experience led to action camps being adopted as as tactic by climate change campaigners, and Camps for Climate Action took place outside Drax Power Station (2006), Heathrow Airport (2007), Kingsnorth Power Station (2008), the financial centre of London (2009) and the Royal Bank Of Scotland’s headquarters (2010).

The early Climate Camps were in fact targeted by officers from both the SDS and the NPOIU, and the Climate Camp legal team is a core participant in the Inquiry, and has submitted a witness statement for Tranche 3.

Geffen is just asked about NPOIU officer Mark Kennedy, then known to everyone at the Camps as ‘Mark Stone’. Kennedy was involved in the Climate Camp’s land group, the core secret subgroup that identified sites for the camps. Geffen says he was unaware of this at the time.

Kennedy was based in Nottingham while Geffen was based in London, so he did not know Kennedy well beyond being a familiar face.

Geffen was part of the Climate Camp legal team at the inaugural Drax camp in North Yorkshire, taking care of anyone arrested at the event. Kennedy was part of a large group of people at an action a long way away, at Hartlepool nuclear power station.

Kennedy had locked himself to the gates and was among those arrested. They were released very late at night, and Geffen organised the transport to get them all back.

Geffen says it is highly likely Kennedy was party to conversations between activists about their arrests:

‘Particularly given that he was arrested himself at this action… I’ve little doubt that he was party to conversations with his co-arrestees about the circumstances of their arrest.

And I would really urge the Inquiry to ask him what information he gleaned from conversations like that because I’ve little doubt that would have taken place.’

When they arrived back at the camp from Hartlepool, Kennedy was driving, and he drove the van straight at a police officer standing in the gateway, forcing him to run out of the way for his own safety.

Geffen says he didn’t confront Kennedy over his behaviour, but it did strike him as odd.

‘It just struck me as: he is showing off…

he was known for regularly wanting to kind of incite more disorder, a more confrontational attitude, and this was just a part of a pattern of Mark Kennedy’s behaviour.’

Like Boyling, Kennedy’s traits were not unique. The Inquiry has heard numerous descriptions of undercover officers being more aggressive than the rest of the group, and being disparaging about those who are less bellicose.

Geffen is also asked about the second Climate Camp, which took place at Heathrow in 2007. BAA, the owners of the airport, took out an injunction, which Geffen describes as:

‘another example of a strategic law suit against public participation…

it included injuncting people and organisations who were involved… which included groups like the National Trust – Patron, the Queen.

It would have ultimately meant that the Queen was not allowed to travel on the Piccadilly line to Heathrow…

It was that absurd in the scope of what was prohibited under the injunction.’

This use of civil law and injunctions to prevent protest is an important theme that emerges in the Inquiry’s Tranche 3 era (1993-2008), and non-state Core Participants have asked the Inquiry to really look at the appropriateness of any role undercover officers might have played in these processes.

Finally, Poulsen asked Geffen about the raid of school in Nottinghamshire where 114 people had assembled for a briefing, prior to a planned action at Ratcliffe-on-Soar Power station.

Spycop Mark Kennedy under arrest in the Ratcliffe power station protest planning venue, Nottingham, 13 April 2009

Geffen was arrested there, alongside spycop Mark Kennedy, and 112 others.

Geffen points out that most of these people were not charged with anything, presumably to hide that fact that one of the arrestees was a police officer – prosecuting him would have presented problems for the police so, despite his key role, Kennedy was not charged.

Twenty people were convicted though, but their convictions were later quashed when it emerged that the prosecution had deliberately withheld recordings made at the briefing by Kennedy. These would have supported their defence that they were genuinely seeking to prevent carbon dioxide emissions by shutting down the power station.

It is noteworthy that the Director of Public Prosecutions at the time was Keir Starmer, who helped ensure that CPS staff and spycops avoided accountability for orchestrating these wrongful convictions – a number of core participants, including Geffen, have called for Starmer to give evidence to the Inquiry.

A significant number of core participants were arrested at Ratcliffe and it is likely to be a significant issue for the Inquiry in when it covers Kennedy’s deployment in Tranche 4.

OTHER QUESTIONS

Geffen is asked a number of other questions, such as whether he knew undercover officer HN78 Trevor Morris. Geffen has no memory of him, however it is evident that Morris reported on him, including recording his bank details.

This prompted Geffen to ask further questions about whether there is other relevant reporting from other spycops such as Morris, HN2 Andy Coles or HN43 Peter Francis that the Inquiry has not shown him.

Poulsen also asks about a spycop’s report stating that Geffen once gave the judge a Nazi salute in court. He explains that this was a reaction to an abuse of process where the magistrate repeatedly extended their bail conditions, and questions why this petty anecdote is being raised at all:

‘I do wonder firstly, why is that question relevant to an inquiry on police spying? Was a rather silly gesture of contempt for the magistrate a justification for undercover policing?

And secondly, who was the police officer who recorded the intelligence about that and… what legally privileged information he might also have been party to on that occasion.’

Asked whether he ever used pseudonyms, Geffen explains that it was common practice for pseudonyms to be used when talking to the media in order to avoid stories becoming personalised or focusing on the individuals rather than the issues.

Finally, Geffen is asked about the impact of being spied on. He explains that it’s unsettling, especially knowing that they were right at the heart of our social networks, and again he wonders why some of the people who were much more closely affected have not been called to give evidence.

CLOSING SPEECH

At the end of his evidence Geffen delivers a very eloquent speech setting out all the questions he feels the Inquiry has not addressed, which we encourage you to watch in full:

He talks about police informers, particularly the convicted paedophile Edward Nicholas Gratwick who infiltrated environmental campaigns in the 1990s and 2000s. Geffen asks how much the police knew about the child abuse offences their employee was engaged in.

He asks the Inquiry to investigate the police tactic of confiscating huge numbers of leaflets, not only in the Evading Standards incident, but also in the run up to Reclaim the Streets’ Mayday 2000 demonstration where disclosure of police fiels reveals a detailed police plot to harass and specifically target RTS’s printed material, even contemplating raiding the print shop where the material was being produced.

Geffen asks why the police created so much disruption and discord, and why the police repeatedly tried to conflate Reclaim the Streets with terrorism, citing an incident where police planted an incendiary devices on an activist which went off in his home, following a protest against the Terrorism Bill.

The media were given detailed, entirely fabricated, stories along these lines. The Sunday Times reported that, ahead of a protest on 30 November 1999:

‘At least 34 containers of CS gas and four stun guns capable of delivering a 50,000 volt electric shock were purchased by Reclaim the Streets.’

RTS took the issue to the Press Complaints Commission who agreed there was no basis for the story but, as RTS wasn’t a formal organisation, it couldn’t be defamed and so rejected the complaint.

Leaflet for Carnival Against Capitalism, organised by Reclaim the Streets on June 18 1999 in the City of London. Spycop Jim Boylinjg was a planner yet his information wasn’t passed to City of London police.

Geffen also sets out the evidence (examined in more detail in the RTS witness statement to the Inquiry) that the police were actually using the intelligence gathered by the SDS to make disorder more likely.

Why was evidence collected by Boyling about the plan for J18 not passed on to City of London police who were responsible for public order policing on the ground?

Geffen asks the Inquiry to call police force commanders of the time, such as Anthony Speed and Perry Nove from the Met and City of London police respectively, to explain what happened.

Geffen concludes by saying that there was simply no justification at all for what the SDS did. They knew the intentions of the RTS to hold family-friendly events, yet they acted as agent provocateurs and painted us as terrorists.

He points out that only a week ago the government had to publish a report from its own national security services about the grave security implications of the current climate and ecological crisis – a report that the government had balked at publishing due to the severity of the facts, and had been forced into releasing a redacted version by concerned citizens using a Freedom of Information process.

Geffen asserts that the real threat to national security was the SDS who went to such lengths for so long to prevent us from getting our message across.

The Inquiry’s Chair, Sir John Mitting, rather awkwardly thanks Roger Geffen for attending, adding:

‘We’re a free country. Um, despite all the difficulties that, uh, I am examining. Thank you.’

This was met with laughter from the public gallery.

Immediately after the hearing concluded, Geffen spoke to Tom Fowler: