UCPI – Daily Report: 10 & 11 February 2025 – HN69 Malcolm MacLeod

Spycop manager HN69 Malcolm MacLeod giving evidence at the Undercover Policing Inquiry, February 2025

Special Demonstration Squad manager HN69 Malcolm MacLeod gave two days of evidence to the Undercover Policing Inquiry on Monday 10 and Tuesday 11 February 2025.

MacLeod spent just under a year in charge of the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS), between November 1986 and September 1987. He was a newly-promoted Detective Chief Inspector who was the overall boss of the spycops unit, with Detective Inspectors under him running the day-to-day details of deployments.

Prior to joining the SDS, MacLeod worked on Special Branch C Squad’s ‘alternatives’ desk which monitored animal rights and anarchist groups like London Greenpeace. Although his tenure was short, it was at a time of special interest to the Inquiry. This was the period when HN10 Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’ was infiltrating an Animal Liberation Front cell that planted timed incendiary devices in shops that sold fur.

Lambert has strenuously denied planting any devices, but numerous witnesses and all the circumstantial evidence shows he was responsible for the one in the Harrow branch of Debenhams department store.

Lambert’s managers – not just MacLeod but others who testified like HN32 Michael Couch and HN39 Eric Docker – have all claimed to have been so useless at management that they didn’t know what Lambert was doing. Nor did they notice the mysterious long gap in Lambert’s reports to them during the weeks leading up to the Harrow store being targeted.

There’s more to this than Lambert, too. The managers all give significant insight into how the SDS was organised, and how its lack of oversight and accountability led to horrendous abuses such as sexual violation of women and the engineering of miscarriages of justice.

MacLeod was questioned for the Inquiry by Emma Gargitter.

This is a long report, use the links to jump to specific sections:

Joining the SDS

MacLeod’s background and what he found in the SDS

Recruitment and training

‘Pretty piss poor’ system for hiring, stealing identities of dead children, what to do undercover.

Pitfalls and problems

Breaching judicial principles, no personal support, officers going awry, MI5 muscling in

Relationships in principle

A range of responses to the idea of whether officers could and should have been prevented from deceiving women into relationships

Specific relationships

Mike Chitty, John Dines, John Lipscomb, and Bob Lambert

Spycops committing crimes

How far should they go, and how would they know?

Bob Lambert in the Animal Liberation Front

The largest section of this report, covering the incendiary device campaigns and ensuing court cases

Targets

Why were spycops spying on the Trevor Monerville justice campaign, MPs, the McLibel campaign, and the women’s peace movement?

The UCPI is an independent, judge-led inquiry into undercover policing in England and Wales. Its main focus is the activity of two units who deployed long-term undercover officers into a variety of political groups: the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS, 1968-2008) and the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU, 1999-2011). Spycops from these units lived as activists for years at a time, spying on more than 1,000 groups.

This hearing was part of the Inquiry’s ‘Tranche 2 Phase 2’, which mainly concentrated on examining the animal rights-focused activities of the SDS from 1983-92.

Click here for the first day’s page on the Inquiry website.

Click here for the second day’s page on the Inquiry website.

JOINING THE SDS

MacLeod joined the Met’s Special Branch in 1969, and had learned of the SDS’s existence from his Branch colleagues. He says he was aware this was a covert operation funded by the Home Office to obtain intelligence about political activists.

Eric Docker giving evidence at the Undercover Policing Inquiry, 28 January 2025. He served under Malcolm MacLeod running the Special Demonstration Squad.

He knew that many of the intelligence reports that he saw on the ‘alternatives’ desk at C Squad came from the SDS spycops. C Squad was one of the main ‘customers’ for SDS reports. We see an example of an SDS report, dated 27 August 1986 [MPS-0742828]. It’s been annotated by MacLeod at C Squad, showing who he wanted it disseminating to.

MacLeod says that ‘the majority of the reports went to ARNI’ (the Animal Rights National Index). He goes on to explain that this unit was begun by the Essex police, who collated information about animal rights activists. The Home Office then established a national organisation so that intelligence could be shared between different constabularies.

MacLeod says this was the first time that police forces around the country effectively shared intelligence of this kind with each other. There was an ARNI office in Scotland Yard. Those who saw the spycops’ intelligence wouldn’t always have been aware of how it had been gathered.

In his witness statement to the Inquiry [MPS-0748808], MacLeod recalls that while he was at C Squad he had at least one phone conversation with an SDS manager. He additionally had a meeting with SDS staff HN39 Eric Docker, HN10 Bob Lambert and HN11 Mike Chitty in a pub so they could brief him on animal rights campaigners.

MacLeod’s statement describes the relationship between ARNI and the SDS as ‘excellent’ and said that information flowed both ways. He explains that after he took charge of the SDS, he was ‘routinely provided’ with information about animal rights activism and would pass it on to the rest of the spycops unit.

After about 10 months in charge of the SDS, MacLeod returned to C Squad around September 1987. He became a Detective Superintendent. He says he remained aware of the work being done by the spycops. It’s extraordinarily rapid promotion, two ranks in the space of a year. Senior officers must surely have felt his time at the SDS was a great success.

GETTING STARTED

MacLeod had never been an undercover officer, and had no first-hand experience of the deployment of undercover officers when he became Detective Chief Inspector of the spycops unit. His DI, Eric Docker, had only been in his role for seven months and says he’d had no handover from his predecessor. Despite this, MacLeod says of Docker:

‘He seemed to me at the time to be fairly bedded in.’

In contrast to Docker, MacLeod says he did have a handover from his predecessor, HN115 Tony Wait. Wait provided him with a pen portrait of each of the spycops officers and their performance, but he doesn’t remember Bob Lambert being singled out.

Tony Wait told the Inquiry that Lambert had told him that he’d ‘got a girl into trouble’ while undercover. He had deceived four women into intimate relationships and had deliberately had a child with one of them.

MacLeod says that Wait definitely didn’t mention this to him, and had he known he’d have been concerned it could significantly affect Lambert’s deployment and the whole squad:

‘I would have to take into account the possible repercussions it would have, not just for the individual but for the operation… I would almost certainly have raised it with the Commander…

Common sense would tell you that something would have to be done if you have an officer who has erred and it’s something that could impact on the operation itself.’

In his statement, MacLeod said it ‘was an honour’ to be asked to head up the spycops unit, a point he elaborated on at the Inquiry:

‘it was quite a unique group of people, who volunteered to serve undercover. They were making great sacrifices in being away from their family for various lengths of time. They chose to do this job out of a sense of duty.

I felt they were an admirable bunch of guys and girls, and to me it was quite an insight, having been for the best part of my career involved in general Special Branch work, this was quite a different ball game altogether.

From Day 1, and from talking to them during the weekly briefings, meetings, you do get a sense of what the sorts of characters are, and why they are doing what they are doing. It is quite a sacrifice of these officers. So, yes it was an honour for me to have been their boss.’

After this effusive praise, he confirms that his view was changed by the knowledge that his officers had deceived women into intimate relationships:

‘It was totally unacceptable behaviour, to the point of being disreputable.’

The SDS Annual Report 1987 [MPS-0728976] describes a visit to the spycops’ safe-house by two senior officers: John Dellow, Assistant Commissioner of Specialist Operations, and Simon Crawshaw, Deputy Assistant of Special Branch.

MacLeod says this was a chance for them to hear directly from the undercovers and learn more about the work they were doing, and appreciate its value. Officers would have said what groups they spied on and mention perceived successes, but not gone into detail about their methods to the illustrious visitors.

‘They sent a very gracious note, a memo, afterwards thanking us for the opportunity to address the meeting.’

This tallies with numerous reports we’ve heard at the Inquiry of extremely high-ranking officers visiting and congratulating the spycops. It demolishes the Met’s desperate claims that the SDS was a super-secret unit practically unknown to the rest of the force.

RECRUITMENT AND TRAINING

MacLeod chaired the SDS selection panel that appointed new recruits.

In his statement to the Inquiry, MacLeod said that SDS spycops were recruited by DCIs of various Special Branch squads putting forward candidates. Gargitter asks him, if the work of the SDS was not widely known, how would they know to put people forward to join it?

MacLeod floundered around, stopping and starting, before arriving at the idea that the managers could give their personal opinion on someone’s suitability to gather intelligence.

But, Gargitter says, if they didn’t know about the role then they couldn’t know about someone’s suitability for it. MacLeod replied:

‘Well, I mean, yes, that has to be said, yes. That is true.’

Either this obvious conundrum didn’t occur to MacLeod and his colleagues at the time, or else he’s lying and the bosses of other squads were much more aware of what an SDS undercover’s work involved.

In his statement, MacLeod says the ignorance extended beyond the squad’s managers, and even claims that applicants themselves weren’t really aware of what they were applying for:

‘the candidates were asked what they believed the role to entail, its disadvantages and advantages.’

FAMILY INVOLVEMENT – MARRIED MEN PREFERRED

He said that, before deployment, it was imperative to meet the new officer’s spouse and talk about the pressures that would come with the role:

‘It’s a long time, four and a half years, working in circumstances that the families would be unacquainted with, and the pressures that brings on the individual officer.

So the families can only have a sort of brief understanding of what the work is going to entail. It’s only when they get into the job they realise the length of time they are going to be spending away from the family home.’

There were no checks made with families to monitor their welfare, and it would be up to the officers themselves to sort such problems out.

Asked if there were any provisions in place that the families could access or use if they had any concerns whilst their family member was deployed undercover, MacLeod says:

‘Sadly not.’

Why ‘sadly’? MacLeod flounders once more, eventually saying:

‘It’s very difficult to give an answer to that’

He confirms that there was no way for a family to check if their spycop was safe.

MacLeod clearly remembers that at the time it was thought that married officers would make better undercovers:

‘I do believe it does help to form, if you like, an anchor with their real lives. And I think that probably holds a lot of sway when you compare it with, perhaps, a single officer, who doesn’t have that home life or that stability, if you like, to keep him on the straight and narrow.’

Why would that apply to spouses but not parents or siblings, though? Was the difference that a married man was believed to be less likely to enter into a sexual relationship while undercover?

‘That was the received wisdom at the time.’

It is clear that Malcolm MacLeod is finding it difficult to give evidence. He is perhaps the most believable user of forgetful mannerisms among former spycops and managers, occasionally losing his way on what the question was as he answers.

‘PRETTY PISS POOR’

Spycop HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’ while undercover. He was hired by MacLeod’s ‘piss poor’ selection process.

In 2012, MacLeod was interviewed by Operation Herne, an internal police investigation into spycops. In his statement to them [MPS-0726640] he described the SDS selection process as ‘pretty piss poor’.

Do you stand by that description now? After apologising for the language he used, he agrees that yes, he does.

MacLeod’s view is that some kind of aptitude test could have been used to weed out the likes of HN11 Mike Chitty ‘Mike Blake’ from becoming a spycop in the first place. After his deployment ended, Chitty secretly returned to his social life among the people he had spied on.

MacLeod says they could have used some form of psychometric or aptitude testing, as has subsequently been implemented. He didn’t actually recommend it to his superiors at the time though, nor any other improvements.

While he was running the unit, three undercover officers were recruited: HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’, HN87 ‘John Lipscomb’ and HN25 ‘Kevin Douglas’. We now know that at least two of these three men deceived women into relationships while undercover.

MacLeod responds:

‘You know, with a bit of a hindsight, perhaps something should have been done…

If somebody is so minded to stray like that, it’s pretty abhorrent, but I am not really sure there would be an effective way of preventing that, apart from warning them and making sure that this is just totally unacceptable.’

This answer set a pattern we see throughout MacLeod’s evidence – conceding abuses were wrong yet not only admitting he didn’t do anything to prevent them, but claiming that there was nothing he could have done.

In his statement, he mentioned a binder kept in the SDS office. This was an internal binder, which he read through, full of advice and guidance for members of the spycops unit, about how to build up their ‘legends’ (cover identities and back stories).

He says it wasn’t formally composed but ‘was more organic’, with officers adding advice from their own experiences.

Other officers who were his contemporaries, such as Michael Couch, have testified that there was no such binder.

MacLeod says the advice was mostly about how to build a cover identity, and that new recruits would certainly have been shown it:

‘This is information that’s critical to their deployment.’

In 1993, HN2 Andy Coles ‘Andy Davey’ had just finished his deployment and updated the binder, which has been published by the Inquiry as the SDS Tradecraft Manual.

WHERE ARE THE BOUNDARIES?

MacLeod told the Operation Herne team that the spycops ‘all knew the boundaries’. Asked to explain what he meant by this, he said in his written statement:

‘They were adults and they should know the dictates of moral and common sense: there are certain things you do and do not do. There are fundamental principles that you adhere to whatever role you are in. These include moral principles – decency and probity were qualities we looked for in officers.’

We should remember that he is referring to a unit whose entire activity was unlawful. They stole the identities of dead children, violated fundamental human rights, engineered miscarriages of justice, sexually abused women, and then joked about it all with one another.

His witness statement adds:

‘I did not satisfy myself in the case of every individual officer that they knew all the boundaries, but felt that I could safely assume it to be true.’

If you didn’t discuss lines or boundaries with the spycops officers, how would they have known where these lay? MacLeod accepts that in the absence of any clear guidance, officers would be left to make their own personal and subjective judgement.

He admits that he didn’t sit them down and spell out such guidance when they first joined the spycops unit:

‘I keep coming back to this 20/20 hindsight. Had I known then what I know now, yes, should have done.’

It’s amazing how many of these officers say that with hindsight their actions weren’t justifiable, but then they still try to justify it all.

And on the occasions when, as with this question, they admit to it being unjustifiable, they use phrases like ‘20/20 hindsight’ to imply that only unattainable perfection could have moved them to act any differently at the time.

DRINK-DRIVER SPYCOPS

In his statement, MacLeod described what he learned from his time running the SDS:

‘It opened my eyes to the risks associated with undercover work, such as risk of compromise and risk of abhorrent behaviour (eg with alcohol). It was a salutary lesson in terms of human frailty.’

MacLeod clarifies that he’s only referring to one officer who had an alcohol problem and was arrested for drink-driving.

MacLeod claims that he learned about the ‘root causes’ which led the officer to drink to excess, and the ways in which he could have perhaps have picked up on clues about their officer’s state of mind.

He then, again, goes on to contradict himself and say he doesn’t see how he could have done anything differently, so absolving himself of any blame:

‘I don’t think there’s very much more that really I could have done, if you like, to ameliorate or to prevent this sort of thing happening… No, I am quite relaxed about it.’

As generations of spied-on activists can attest, many other spycops were problem drinkers too. And, just like the officer MacLeod knew, an earlier spycop HN339 ‘Stewart Goodman’ crashed his car while drunk and was arrested. Goodman broke protocol by admitting his real identity and job to the uniformed officers who attended, and was convicted for drink-driving under his false name.

MacLeod refuses to accept that he should have provided more guidance to the spycops:

‘They are grown men, they should know better. They know right from wrong. You know, there is only so much you can do to sort of wet nurse them’

It’s horrendous that he can admit to gross failings of officers, and then dismiss any suggestion that he should have properly acted as their manager, speaking as if doing so would have been somehow infantilising them.

Emma Gargitter challenges him on his claim that ‘they know right from wrong’ and, not for the first time, MacLeod crumbles and contradicts himself:

Q: A number of the officers under your command don’t appear to have been able to identify right from wrong or if they did, were willing to do the wrong thing?

MacLeod: Yes, I am afraid, sadly.

He is very clear that he does not consider the sexual deceit to be a result of any ‘human frailty’ under discussion, and those abuses were instead a case of the spycops exploiting an opportunity.

IDENTITY THEFT

We hear about the method used by spycops to create their cover identities: stealing the name of a deceased child. New recruits would spend six to eight months working in the unit’s back office, during which time they would find the birth and death certificates of a child whose identity they would steal.

MacLeod says he only learned about this practice after he joined the unit.

He says it never occurred to him to question whether this identity theft was legal, and he says he didn’t ask any superiors about it. He says he felt uncomfortable with ‘the very idea’, but:

‘It was designed to provide maximum protection for the undercover officers in building up their legend. So, no, although I had some personal qualms about it, I just accepted that that was how things were done.’

It wasn’t the most secure tactic though. If they simply made up an identity and someone in the officer’s target group became suspicious and investigated, there would be no birth certificate to find. However, that could be explained away (born abroad, adopted, etc). Whereas with a stolen identity there would be a death certificate that cannot be explained for someone who isn’t actually dead. It would prove the person was some sort of spy.

This is exactly what happened to HN297 Rick Clark ‘Rick Gibson’ in 1976, only a couple of years after the spycops started the identity theft method.

The grave of Mark Robert Robinson whose identity was stolen by spycop Bob Lambert. Branksome cemetery, Poole, Dorset.

MacLeod says he knew Clark later. He knew Clark had been an SDS officer in the 1970s, and that he was known as ‘a ladies’ man’. However, MacLeod claims it wasn’t until long after he left the police that he heard about the incident that ended Clark’s deployment when he’d been confronted with ‘his’ death certificate.

He says he only realised how ‘abhorrent’ the situation was when the spycops story ‘hit the media’ and he learned how the families of these deceased children felt about this identity theft. He says it didn’t occur to him at the time.

This is the man who just said how officers knew right from wrong, yet not only admits they all did something wrong, but that at the time he was essentially oblivious to the fact that it was wrong.

Neither did the possibility of any impacts on the families occur to him (e.g. the spycops getting a criminal record and violating citizens in their loved ones’ name, or people investigating the spycop and turning up at the family’s home looking for their dead relative).

He doesn’t remember any officer checking to see where the remaining family were, or visiting the area where they lived. However, numerous officers have testified that they did this, and MacLeod says he would have viewed that as legitimate and necessary at the time.

WRITING THE REPORTS

In his statement to the Inquiry, MacLeod said that SDS officers were given no instructions about what to include – and what to omit – in their intelligence reports.

He says it was something they should have picked up on the job based on what they had learned during their time in Special Branch; they didn’t need any specific instruction when they became spycops, and would get six to eight months in the SDS back office processing other officers’ reports before making any of their own.

It’s pointed out that full-time undercover officers would come across a huge amount of information about the people and groups they spied on, far too much to report, and so would inevitably have to decide what to include. MacLeod says this was entirely left up to the officer and they were never given any guidance.

He says he cannot remember ever telling an officer that something they reported was unhelpful, irrelevant or inappropriate in any way.

In his witness statement, MacLeod says he took a keen interest in the form and contents of the reports:

‘I made a conscious effort to read as much of the reporting as I could, though I could not read all the reports. Obviously the team would flag anything of particular significance as a priority for me.

It is not only useful to get an insight into what was happening but also some sense of the effort that each undercover officer put into their report-writing, style, credibility, et cetera.’

MacLeod says it was Eric Docker who would read all the reports and pass on the important ones.

This squarely contradicts what Docker told the Inquiry. He tried to dodge accountability by saying that he only gave reports a cursory check for grammar and spelling, and didn’t pay ‘great attention’ to the actual contents of the reports that he signed off.

It’s also something MacLeod himself contradicts later on, claiming not to have seen reports on important events he claims to be unaware of.

MacLeod’s written statement also says that spycops reports were typed up by Detective Sergeants. He is unaware of any editorial control taking place at this stage and wouldn’t have expected any, apart from alterations to grammar rather than the substance.

This is an important point. The managers all say this, and reports do seem to have distinctive voices of the authors, yet numerous undercovers have tried to avoid culpability for particular parts of their reports by suggesting that managers had inserted or omitted certain details at the typing-up stage.

MISOGYNY

We were shown a report by spycop HN95 Stefan Scutt ‘Stefan Wesalowski’ [UCPI0000020148] dated 22 April 1987. It had been written in response to a request from the Security Service (aka MI5) about the Hackney South branch of the Socialist Workers Party.

Scutt refers to a woman as ‘plump build, pretty face’. MacLeod denies that this is offensive or misogynistic. He does, however, accept that it’s derogatory, subjective, and unnecessary.

Asked if it’s indicative of the culture of the SDS, MacLeod replies:

‘It’s more of a comment on the time, in the 1980s when language like this was probably seen to be acceptable.’

He goes on to claim it wasn’t common to hear SDS officers comment on women’s attractiveness and in fact he never heard any other officers do so.

In his written statement, MacLeod said:

‘People today have got higher expectations of public bodies and the police are open to greater public scrutiny than they were.’

Gargitter draws this point out. If public scrutiny keeps the police on the straight and narrow, then the high levels of secrecy around the SDS effectively gave them a cloak for behaviour that, in more public areas of work, might have been called out.

MacLeod agrees with this. He admits that at the time he wasn’t concerned about the level of intrusion, or the kind of reports the spycops produced.

PITFALLS AND PROBLEMS

LEGAL PROFESSIONAL PRIVILEGE

Spycops reported on people’s legal strategies and were in meetings that activists held with their lawyers, often because they themselves had been arrested and were defendants in cases. This breached the principle of ‘legal professional privilege’, a fundamental part of the judicial system where lawyers and clients should be able to discuss matters in confidence.

Beyond this, many spycops went to court under false identities, swore to tell ‘the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth’ and then from the very first question asking their name, they lied. This is perjury.

Additionally, courts have a duty to ensure all material is available to the defence. By withholding the truth about spycops and their reports, the SDS misled courts. This means the trials were unfair and any resulting convictions were miscarriages of justice.

MacLeod says he was aware of legal professional privilege from courses he’d been on before he was in the SDS:

‘I would be uncomfortable with sanctioning anything that troubled me as being legally privileged. I would prefer to have it removed from the report. If it smacked of breach of legal privilege, I would have been very uneasy. There would be reputational repercussions if it became known…

It would be fundamentally wrong. In fact, it would be breaking the law.’

Spycops routinely committed crimes like identity theft and perjury, as well as encouraging and participating in criminal acts among the groups they spied on. The entire SDS operation was unlawful. The idea of ‘reputational repercussions if it became known’ should have set alarm bells ringing long before this point.

Despite his current assertion that he would have removed any privileged information from reports, MacLeod can’t remember ever actually doing so:

‘There was no policy, instruction or guidance concerning officers coming into possession of legally privileged information.’

SPYCOPS MEETINGS

The spycops met twice a week at their safe-houses. The whole unit would meet, including Eric Docker and the sergeants who did the admin work. MacLeod would brief them on issues and events in the wider policing world. Each officer would speak in turn about their deployment. It would be detailed, naming individuals who were spied on and discussing what they’d done.

MacLeod explains the value of these meetings for the unit:

‘Just the camaraderie alone, and talking with colleagues, talking in police language…

Because bear in mind they are away from their place of work. They are not mixing with police officers, their colleagues. And it’s a safety valve for them. So it was a very valuable sort of exercise, and that’s why we had meetings twice a week.’

After the communal go-round there would be ‘side meetings’, and MacLeod confirms that he and Docker had more of these with Bob Lambert than with other officers.

MacLeod’s 2012 written statement to Operation Herne is shown [MPS-0726827], in which he says that spycops officers would drink alcohol and play pool and darts after the safe house meetings. He would usually stay with them for a few hours, drinking beers:

‘It was a great opportunity for these guys and girls to actually sort of find some space, because living cheek by jowl with the activists can be a bit tiresome and a bit tedious’

Asked if any of the banter during the social sessions was sexist, MacLeod admits:

‘It may have been.. you have to turn the clock back all those years, living in a different age. Being brutally frank, there wasn’t the same awareness at the time about sexism and so forth.’

He denies that there was any discussion of the attractiveness of women, or that anything racist was ever said.

NO PERSONAL SUPPORT

The spycops were ‘a very difficult bunch of officers’ because of the strains they were living under as part of their role, especially concerning their real lives away from deployment.

MacLeod says he felt strongly about their welfare while undercover, but again admits these meetings were the only way to monitor it, that it was reliant on the officers, and – using his ‘20/20 hindsight’ phrase again to absolve himself – says he did nothing to improve the arrangement.

Managers had no other sources of insight, and there was no professional mental health support in those days. He says that the spycops would have benefited from having access to a military psychiatrist, as did happen later.

MacLeod says in his statement that if proper post-deployment counselling had been available:

‘I’d have jumped on it.’

INFORMAL MENTOR FOR EX-SPYCOPS

Shortly before MacLeod’s arrival at the SDS, HN115 Tony Wait had set up a spycops ‘buddy-buddy’ informal mentoring scheme, in which an experienced ex-undercover officer would keep in touch with an SDS officer for around six months after their deployment ended and they adjusted back into their old life.

MacLeod says only one officer did this while he was running the unit. In his statement he has written in glowing terms about HN68 ‘Sean Lynch’, who provided a sympathetic ear to other spycops.

HN68 ‘Sean Lynch’ had been undercover 1968-1974 infiltrating the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign, Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association, Irish Civil Rights Solidarity Campaign and Sinn Féin (London), then returned to the SDS as a manager from 1982 to 1984.

MacLeod confirms that the buddy-buddy system didn’t amount to much beyond having the phone number for Lynch, but says he ‘would expect’ other officers to have done it afterwards.

Asked if there was any consideration of the suitability of a former spycops officer for taking on a mentor role for current SDS officers, MacLeod confirms that there were no checks or assessments.

He concedes that it would have been problematic for someone like Bob Lambert to do it. Yet, at the time, Lambert was feted and decorated, then put in charge of the unit. Officers he oversaw were told that his had been ‘hands down the best tour of duty ever’. He would surely have been seen as ideal.

MacLeod says he felt it was part of his role to detect when officers were under stress. But under questioning, he admits that his only opportunity to look was at the twice-weekly group meetings:

‘The thing is, it’s not that easy to detect, unless there’s some manifestly obvious behaviour. There’s no way of knowing.’

He also admitted that he wasn’t at the SDS long enough to get to know spycops to sufficiently assess their stress or competence.

ERRANT OFFICER MIKE CHITTY

A post-deployment psychiatric report of HN11 Mike Chitty ‘Mike Blake’ said he was ‘psychologically unsuited to this type of work’.

MacLeod said in his witness statement that both he and Docker agreed with that assessment:

‘We had some concerns but I cannot now recall the substance. I did not trust him but cannot tell you [now] why that was. I did not provide him with any emotional supervision and/or support during his deployment…

It’s not something you can easily pinpoint. The word ‘shifty’ comes to mind. There are some people who you take a liking to and others you do not. Perhaps we can call this a copper’s instinct.’

Chitty’s spycops deployment was due to end soon. MacLeod didn’t take any action to speed up his withdrawal, saying it didn’t occur to him that he could do this.

But once again, his position crumbled under questioning. Asked why he didn’t do anything to monitor what Chitty was up to, he admitted:

MacLeod: I suppose my comments are based on what I was told about his behaviour.

Q: Do you mean told at the time or told subsequently?

MacLeod: Subsequently, yes.

Q: So there is an element of retrospective analysis, is there?

MacLeod: There is.

Chitty is known to have kept and continued using his fake cover identity documents after leaving the SDS. He returned to the people he’d been spying on and continued his social life with them, deceiving a woman there into a relationship.

Hewas only caught because he was claiming petrol expenses from the place he’d been spying, which he had no reason to visit on duty.

MacLeod says he’s shocked that Chitty retained his fake identity documents, but that there was no rigid process in place to collect them from spycops at the end of deployments. Not even ones who had a negative response from their manager’s intuition.

In his written statement, MacLeod said of Chitty:

‘I cannot honestly remember if he got any counseling. If he did not, he should have.’

But, once more, when questioned he admits that’s a retrospective opinion, and when he was Chitty’s manager he did not do anything to make it happen.

ERRANT OFFICER STEFAN SCUTT

We moved on to discuss HN95 Stefan Scutt ‘Stefan Wesalowski’, an officer under MacLeod’s command whose deployment went awry and had to be withdrawn.

We’re shown an Annual Qualification Review (AQR, the personal appraisal) written by Eric Docker in April 1987 [MPS-0746943], praising Scutt’s work:

‘A thoroughly sound and practical officer, ideally suited to his present duty where his quantities of initiative, self-discipline and experience are put to excellent use. Consistently produces work of the very highest quality.’

It concludes with a recommendation that Scutt be promoted.

Asked if he agreed with the sentiments, MacLeod replied:

‘I am not sure. I would say no.’

But, yet again, when questioned he admits that he’s backcasting his current opinion on to his past. He says he can’t remember what he thought of it at the time. When offered the explanation of Docker writing it without MacLeod ever seeing it, he grasps it with both hands and says that’s the most likely thing.

Next, we see at note to MacLeod from the Security Service dated 16 July 1987, thanking him for a meeting with Scutt [UCPI0000024603]. MacLeod says he can’t remember it. He is asked if he is surprised by it, and says he doesn’t know.

We are shown a report about a Security Service visit to the SDS on 16 September 1987 [UCPI0000022281]. Docker was there, MacLeod wasn’t. It says Scutt has:

‘Two years to go and continues to do very well.’

MacLeod doesn’t agree with this description either, but once again admits this is based on what he knows now. He says he can’t remember what he thought at the time, though:

‘I remember there were issues, but I can’t remember specifically what these issues were.’

It is pointed out there is nothing to suggest any dissatisfaction from him about Scutt in the paperwork from the time. Asked if he agrees with that, he oddly responds:

‘No, I can’t comment.’

Gargitter asks for more documents to be shown, saying to MacLeod:

‘Let’s see if we can jog any memory that you might have.’

THE SECURITY SERVICE

Next, we see a Security Service note of a meeting they held with MacLeod and Scutt on 13 February 1987 [UCPI0000024630].

It details Scutt being invited to work inside the headquarters of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP). This is described by the Security Service as a ‘unique honour’ for someone who hasn’t been a member of the Party for very long.

MacLeod says he cannot recall it.

The Security Service think Scutt taking up the role could provide them with lots of valuable intelligence, but the Met veto the idea, and give multiple reasons.

MacLeod says he agrees that ‘this is a police operation’ and that he would not be comfortable with letting the Security Service have too much say. He can’t recall any discussion of this with anyone further up the chain.

He agrees that there would have been a concern about SDS officers straying too far from their role. The note also reports that:

‘HN 95 arrived before MacLeod and was able to share with us the disappointment raised by the refusal of his masters to allow him to take up the job in Socialist Workers Party administration which he has been offered.’

MacLeod doesn’t recall this either. He says it wasn’t normal for such direct communication to take place between the Security Service and individual spycops – he says if he’d known, he would have reminded them to go through the management.

About a year later, Scutt had his deployment prematurely terminated. MacLeod says he cannot remember anything about concerns over losing control of Scutt. He doesn’t admit to remembering very much about Scutt at all.

MacLeod reported to Chief Superintendent HN84 Ray Parker. It seems that, shortly after Scutt’s interactions, in the summer of 1987 Parker reiterated to the Security Service that any arrangements to meet with SDS officers had go through him, and be requested in writing.

In his statement, MacLeod has written about the influence the Security Service sought to exert over the SDS, saying it ‘bordered on control’, as well as its ‘informal influence’:

‘The Security Service actively tried to maintain good relations with the SDS management, including by providing corporate hospitality.’

He agrees with the evidence we recently heard from Eric Docker: the flow of information tended to go in one direction only, from the spycops to the Security Service.

SCUTT’S MISOGYNY

Another document shows that Docker and Scutt had a further meeting with the Security Service in July 1987 – complete with a sandwich lunch – at which Scutt complained about the Socialist Workers Party [UCPI0000022317].

He called the women ‘ugly’ and described the Party members as ‘boring’ and too ideological (i.e. they weren’t interested in football and didn’t tell funny stories).

In another of Scutt’s reports [UCPI0000022350], a woman SWP activist is described as ‘fat and ugly’.

MacLeod doesn’t remember Scutt using this type of language verbally. But, yet again at the Inquiry, we either have to think that these men weren’t bigoted in casual company but somehow turned it on when writing official reports, or else they did in fact talk like this.

Q: Is it possible, Mr MacLeod, that that sort of language to describe women was commonplace at the time, and so it didn’t stand out to you? … Did you hear it with some level of frequency within the SDS?

MacLeod: Well, that’s the thing. I may have done, may not have done. I am inclined to err on the side not to have done. Just, I mean, that kind of language is just unnecessary apart from anything else.

Given the instances of this type of language in the reports, alongside all manner of reporting that was unnecessary, this really isn’t the defence that MacLeod thinks it is.

RELATIONSHIPS IN PRINCIPLE

In his witness statement, MacLeod has been very clear about his context for spycops deceiving women into intimate relationships:

‘The majority of officers were stalwart professionals, and I feel strongly that their achievements should not be retrospectively underappreciated or overshadowed by the misconduct of a few.’

He says that such relationships did constitute misconduct. Specifically questioned, he confirms that in his witness statement, he said if he were asked to make a moral judgement, he would be disapproving of such conduct.

Gargitter then reads from the notes made by Operation Herne, a police investigation into spycops, when they interviewed MacLeod in 2012:

‘Although MacLeod did not specifically say that sexual relationships between field officers and their targets were permitted, he made it quite clear that they went on, and to some degree were a part of the job.

In summary, he stated that if a field officer had a close relationship with a target and a sexual relationship was a likely progression of that relationship, and the officer refused or made excuses, then this could have caused unwanted attention and possibly lead to the officer being identified as a police officer.

“The closer a field officer got the better.” MacLeod said that his objective was to get the intelligence, not to make moral judgments.’

It’s clear he’s been lying to the Inquiry all day long. This bluntly says that the relationships were good for getting intelligence which, after all, was the entire purpose of the SDS. They didn’t care, and thought they’d never get caught. He’s been exposed by his own words.

MacLeod: Yes, that’s regrettable. I withdraw that.

Q: Sorry, did you say you withdraw that?

MacLeod: Yes.

Q: And what part, precisely, do you withdraw?

MacLeod: All of it.

MacLeod then interrupts the next question to claim that he did not actually know that spycops officers had deceived women into sexual relationships when he spoke to Operation Herne in 2012 and told them it was part of the job:

‘I had no knowledge of it going on. Hypothetically, I said that, and it’s not right.’

He is flapping wildly in his answers.

Q: So you may have said that to Operation Herne, but it was inaccurate when you said it?

MacLeod: Yes.

Q: Can you think of why you might have told Operation Herne that relationships went on and to some degree were part of the job if that was not your state of knowledge when you managed the unit?

MacLeod: That’s not the state of knowledge that I had.

Q: Why would you have said that to Operation Herne then?

MacLeod: No. I can’t be, I can’t be sure.

‘IT HAS TO BE ACCEPTED’

Gargitter is in full ‘skewering’ mode with MacLeod. She shows him his signed statement to Operation Herne in November 2012 [MPS-0726827]. In it, he said:

‘In terms of relationships between a field officer and their compatriots within their target groups, it is obvious that the closer a field officer got to the key people, the better the intelligence was likely to be.

There may be occasions where relationships formed with women within the group and sexual relationships followed. This is not something a field officer would discuss with his supervising officers, but it has to be accepted that such liaisons will form.’

Further exposed as a liar by his own words, MacLeod desperately grabs on to anything other than the truth. It’s like watching a five year old with chocolate all over their face and hands saying they don’t know where the Maltesers went:

‘It doesn’t mean to say that I am approving of it. Not at all. I think it’s a question of facing up to reality that these things do happen in the world.’

But if the situation is that it wasn’t something that you approved of, and you appreciated there was a risk of it happening, surely it was part of your role as a Detective Chief Inspector to take steps to try to prevent it.

It was at this point that MacLeod could no longer conceal the resentment spycops feel at being exposed, blaming those who seek to bring the truth to light rather than themselves for having such despicable secrets:

‘Well, up until that point, and until the exposé occurred in whenever it is, when Caroline Lucas made a statement to the Commons and exposed everything, until then it hadn’t been an issue. Was I surprised? Perhaps we shouldn’t have been surprised that something like this would happen.’

As with other managers at the Inquiry before him, he says that if he’d asked undercovers about intimate relationships they’d only have lied to him.

Not long before this, he told us that these were men of integrity and probity who always knew right from wrong without needing any discussion or guidance. Now he’s saying that a significant proportion of them were sexually abusing women and would have lied to colleagues and management about it. This doesn’t add up. It seems clear that management knew full well and saw it as part of the deployment.

MacLeod goes on:

‘I think we just have to face up to it. It’s an unpalatable fact but this is what happens when you put people in this kind of proximity to each other.’

That perspective portrays it as if it’s a both-sides fault, rather than the truth: this is what happens when you put misogynist liars in proximity to women they can abuse.

‘Maybe, in retrospect, looking back, there should have been ways in which we might have been able to maybe prevent or counter that from happening. We didn’t.’

He says it was made clear to the spycops at the start of their deployments that such relationships were unacceptable. This isn’t the get-out he thinks it is; it’s an admission that he knew of the likelihood and risk yet he claims he did nothing at all to monitor it.

MacLeod’s next graphene-slender excuse for not raising the subject of relationships with officers is that most of them had been recruited by someone else.

He adds that he was only in the spycops unit a short time and that most SDS officers had been serving for years before he joined the unit, as if this somehow absolves him from running the unit, or from setting and enforcing rules as its manager.

He suddenly claims that the ring-binder of informal tips from previous officers included material saying sexual relationships were prohibited:

‘It was in the manual. I mean it’s how much do you – how far do you go in trying to preach to individuals what they should and shouldn’t do?’

‘Preach’, like his earlier use of ‘wet-nurse’, is a way to make it sound as if managers shouldn’t actually manage, and that doing so would be excessive and pompous.

‘All of this has just come about as a result of the 2015 – or whatever it was – exposé.’

This makes no sense on any level. Lucas naming Lambert as the planter of an incendiary device was well after the spycops scandal broke in January 2011. She did so in June 2012. MacLeod then told Operation Herne these relationships were inevitable and useful five months later.

More to the point, it doesn’t matter what date you get discovered violating fundamental human rights. The violation is the thing that should draw anger, not the exposure of it. But, as one who was handsomely paid for facilitating the perpetrators, MacLeod is desperate not to see it that way:

‘Let’s not forget that these behaviours were of a minority when you look at the size of the unit over the years. So it is relatively small.’

In fact, it was endemic and continuous. For almost the entire lifespan of the SDS, there were multiple officers deceiving women into relationships.

Before the afternoon break, we hear the most honest thing MacLeod says all day:

‘You know, it’s in circumstances like this, it’s really, really difficult to defend the indefensible.’

He doesn’t explain why he feels compelled to try.

HN25 ‘Kevin Douglas’ joined the SDS in May 1987, recruited by MacLeod. He told Operation Herne that the spycops were ‘under pressure’ to deliver intelligence, and there were only loose guidelines before the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 (RIPA), and no clear directions about whether they should form sexual relationships with those they spied on.

MacLeod accepts that:

‘In retrospect they should have found another way around it’.

He says that things have changed since the introduction of RIPA (which is odd, because every one of the spycops’ abuses continued unabated after RIPA).

‘I DO NOT BELIEVE THAT WE SHOULD BE SETTING A MORAL CODE’

MacLeod says his style of management wasn’t about turning a blind eye, but that the sexual relationships by spycops weren’t known about in the management team.

His 2012 Operation Herne statement is shown again, with a section that wasn’t read out earlier:

‘The field officers all knew the boundaries and were left to use their common sense when deployed. Extra-marital relations occur in all walks of life and field officers are no exception. I do not believe that we should be setting a moral code for one specific group of police officers to the exclusion of others. This has to be a personal judgment by the officers.’

Gargitter walks him through his statement. He says it’s ‘not a good choice of words’, twice.

These were not extra-marital affairs. They were calculated abuse of women, deceiving them into sex for which they did not give informed consent. The word for that, as many of the women themselves have said, is rape.

It was, in the Met’s own words:

‘abusive, deceitful, manipulative and wrong… a violation of the women’s human rights, an abuse of police power and caused significant trauma.’

Gargitter asks MacLeod if he can see the difference between a police officer conducting an affair in their real identity, and an undercover officer forming a sexual relationship with a target using their cover identity? It appears that he now can.

MacLeod says there was no point in him trying to find out because the spycops would never tell management.

But Bob Lambert has told the Inquiry that he told Detective Inspector HN22 Mike Barber about a relationship he had while undercover. Detective Chief Inspector HN115 Tony Wait recalls hearing from Lambert that he’d had sex with ‘Jacqui’ and thought she was pregnant.

MacLeod absolutely insists that there is nothing more he could have done to prevent his officers deceiving women into relationships. He is asked about his written statement in which he says:

‘There was certainly wrongdoing within the SDS, but it should be seen in the wider context of serious wrongdoing in the target organisations and in the context of the public benefit the SDS provided.’

Asked if he means the sexual relationships here, he’s flummoxed and wants to avoid the obvious answer but can’t think of an alternative that gets him off the hook:

‘I can’t remember. Well, I see it here but “wrongdoing,” I don’t know what I am drawing from that.’

So Gargitter just asks him the same question again. Does it mean it was OK for spycops to do bad things to those who were deemed to be bad people?

‘No, I don’t think I meant that at all. But that’s how it reads.’

SPECIFIC RELATIONSHIPS

HN5 John Dines ‘John Barker’ has made a witness statement in which he has told the Inquiry he made it clear from the outset of his deployment that he intended to get close to Helen Steel, who he did deceive into a relationship.

Helen Steel at the Royal Courts of Justice

Dines was recruited by MacLeod and working in the SDS back office while MacLeod was in charge, deploying just after he left. MacLeod says he simply doesn’t remember him in the back office or ever mentioning Steel.

MacLeod says he was aware of Mike Chitty having a sexual relationship with ‘Lizzie’. He confirms that it was probably Eric Docker who told him, after his time in charge of the SDS. But clearly, that means Docker had been told. So managers did know, then. He’s contradicting himself (and Docker) again.

John Dines feigned a mental breakdown at the end of his deployment and disappeared from Helen Steel’s life. Bob Lambert, who’d risen to be one of the spycops unit’s DIs in the early 1990s, has said that he was aware of Steel’s efforts to look for Dines after he left her.

MacLeod was back in C Squad at the time, one of the main recipients of SDS reports. However, he doesn’t seem to have heard about Steel visiting Dines’s parents’ address.

MacLeod says he remembers hearing about Steel tracking Dines down in Australia, maybe from Eric Docker. He says he is certain that there was no discussion about why Steel might be doing all this.

JOHN LIPSCOMB

HN87 ‘John Lipscomb’ (aka ‘Hippy John’) was deployed in May 1987, under MacLeod’s management, until December 1990. He said in his witness statement that he didn’t think he needed to tell the spycops unit’s managers about the sexual activity he took part in while undercover, unless it became ‘serious’ in some way:

‘I do not think that I told management at the time about any of the above incidents. I managed the situations as well as I could in the circumstances… I did not think it was necessary to tell them. I would have informed them if anything had become more serious.’

MacLeod addressed this claim in his own statement, saying that he didn’t know anything about Lipscomb’s sexual activity. In his view the managers should have been informed of any such behaviour in an undercover identity.

MacLeod has also said in his witness statement that he wasn’t aware of Lipscomb’s habit of staying overnight in activists’ homes, and that managers should have been informed of spycops doing this too. When asked, he says he can’t remember why he said that now.

MacLeod is so desperate to distance himself from all this, he can’t keep up with his own lies, let along gauge whether they’re plausible. He flip-flops again.

Q: You were aware, weren’t you, that officers, including HN87, might be drinking alcohol whilst in their cover identities?

MacLeod: No, I wasn’t aware.

Q: You said in your witness statement that you were “aware that HN87 would drink with the members of his target group. This was, and is, a common way to socialise.” So that suggests you had some awareness that HN87 and perhaps other undercover officers would drink alcohol commonly whilst deployed, is that right?

Q: Yes.

MacLeod accepts there’s an increased likelihood of spycops engaging in sexual activity when drinking with activists and staying the night, but says spycops couldn’t leave such circumstances without risking being exposed as police officers. It apparently:

‘possibly could affect their cover story if they all of a sudden disappeared at an earlier hour and whatever the activist might think, if it’s a female, about leaving a party early. And if there was a relationship.

No, I just, once again we come back to this. I mean this really is something that should be left to the individual’s judgment.’

Wouldn’t it have been a good idea to warn them not to get into situations which might lead to sex?

‘You could but what’s to say they are going to obey it? You wouldn’t know.’

This is the case with any guidance on any other subject though. MacLeod accepts that fact, and pivots from saying there was no point in doing it to saying there was a point after all, but it never occurred to him to give such guidance.

MacLeod: It would be something you would pick up at the next meeting.

Q: But did you ever pick it up at the next meeting?

MacLeod: No, I didn’t.

BOB LAMBERT AND JACQUI

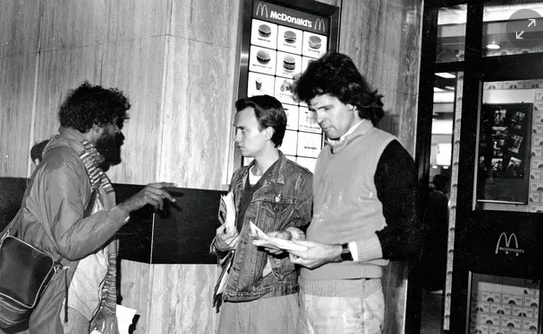

Bob Lambert (far left) with baby TBS at Hopefield animal sanctuary

Next, Gargitter brings up the case of ‘Jacqui’. Bob Lambert, in his undercover identity ‘Bob Robinson’, fathered a child with Jacqui.

The son is known as TBS, born in the autumn of 1985. Lambert continued to act as father to the boy throughout the time that MacLeod was the Detective Chief Inspector of the unit.

MacLeod says he had no knowledge of the relationship or the pregnancy. He says he didn’t hear about Lambert ‘bragging’ about this, as spycop Mike Chitty has described. He says he didn’t know that Lambert was frequently visiting Jacqui in Dagenham and giving her money, seemingly from SDS expenses.

He seems a bit shocked to hear about Lambert taking ‘TBS’ along to activist events, uttering the word ‘extraordinary’ at this point.

In his November 2012 interview with the Operation Herne officers, MacLeod spoke about how Lambert:

‘“outed himself” as a UCO [undercover officer] due to the fact that he lost two children to a rare congenital condition, and as he [Bob Lambert] bore a child from a relationship whilst a field officer, he wanted to contact the mother of the child in order that the child could have tests for the condition.’

MacLeod is wholly wrong about this. Lambert’s children had died but he made no attempt to contact Jacqui. He was outed on 15 October 2011 and it was in the national media the next day. Even then, despite no longer having the secrecy of the SDS to protect, he made no attempt to contact Jacqui.

She came across the truth by chance in a Daily Mail article in June 2012. She tracked Lambert down and his wife later told her about the medical condition.

MacLeod is adamant that he didn’t know about this child when he last saw Lambert in person, at the latter’s retirement party in 2007.

MacLeod says in his Operation Herne statement [MPS-0736832] that he was hugely disappointed that Bob Lambert, unlike other spycops officers, had chosen to speak out. He repeats that he is more disappointed in Lambert speaking publicly about his deceptions of women than in his actually doing it.

LAMBERT AND BELINDA

Bob Lambert and Belinda Harvey

Lambert met Belinda Harvey in April 1987 – again, while MacLeod was running the unit. Like other spycops, he was using a cover identity much younger than his real age. As a result, she didn’t know the age-gap between them was as big as it was.

MacLeod claims not to have realised that many spycops pretended to be much younger than they really were.

The Inquiry has heard that Lambert spent most nights at Belinda’s house in Forest Gate. MacLeod says he didn’t know this, but that Lambert should have told them that he was not staying in his cover flat.

MacLeod says that, due to this Inquiry, he has recently heard that a photo of Lambert and a woman may have been uncovered during a police search of this cover flat.

He is asked if he should have done more at the time:

‘We perhaps could have been a bit more vigilant and proactive.’

HN19 ‘Malcolm Shearing’ gave his evidence to the Inquiry last summer. He said that he accompanied SDS manager HN115 Tony Wait to an event (hosted by the Security Service) back in 1985 and witnessed Wait making a ‘joke in poor taste’ about one of the spycops fathering a child. MacLeod denies hearing about this, or anything similar, ever.

MacLeod’s evidence continued on Tuesday 11 February 2025.

In his witness statement to the Inquiry, MacLeod defined ‘discreditable conduct’ as an officer:

‘behaving in a way that is morally wrong or generally regarded as bad behaviour and where the undercover officer could not show that the conduct was a necessary part of their behaviour in role.’

He cites an officer arrested for drink-driving but says it is also clear that, to him, deceitful relationships, fathering children and committing crimes fall into this category.

Asked about the commission of crimes, he readily affirms his position. But then he backtracks a bit:

‘There may be extenuating circumstances on occasions where it may not be applicable.’

SPYCOPS COMMITTING CRIMES

In his witness statement, MacLeod said:

‘Public order offences were an occupational hazard for undercover officers. They often got caught up in arrests for such offences although I know of no convictions. Public order offences were low level offences, like obstructing the street in demonstrations.

However, there is a distinction to be drawn between low-level public order offences and other acts of criminality, e.g. damage to property (common in the Animal Liberation Front). The latter is a step too far.’

He confirms that this is still his clear, well-defined line about what is and isn’t acceptable for a spycop. He also claims he never told any of his officers about it.

He’s described how different the SDS was to other policing, and how officers applying for the job wouldn’t have known what it actually entailed until after they were chosen. Despite this, he says it was up to them to magically know about his simple rule about which crimes were allowed:

‘Well, I suppose a lot of that is just by intuition. I can’t foresee how one could sit down and have a discussion of what is permissible and what is not. I mean, they are trained police officers. They know right from wrong. There is a limit to how far one can go in terms of wet-nursing mature officers.’

There he is again with ‘wet-nursing’ – any instruction to officers would somehow be demeaning to all parties. And yet yesterday he said he accepted that some of the spycops weren’t very good at knowing right from wrong, or deliberately chose to do wrong. It’s absolutely bizarre that a manager claims that he cannot imagine how one could get officers together and tell them what the rules are.

Gargitter examines the distinction MacLeod makes about spycops being able to break the law in some situations but not others. She says a normal police officer wouldn’t be arrested at all, whereas the spycops might be arrested for public order offences. As they’re going to cross the line into criminality, this surely makes it important to specify how far they should go.

MacLeod blusters a lot of stuff about being caught up in the unplanned moment of a public order situation. Gargitter brings him back to the actual topic, premeditated crimes that he’s said are wrong.

He veers back to saying that managers can’t call workers together to explain how their job works and what the rules are:

‘They have to live by their wits. Once again, it’s perhaps easy to, in hindsight, to state that something should be done to prevent this from happening.’

It would also have been easy to do something at the time, if managers had actually wanted to prevent it. It’s clear that they didn’t.

MacLeod says in his witness statement that animal rights infiltration carried a higher risk of arrest than other deployments.

He says that HN5 John Dines and HN87 ‘John Lipscomb’, officers he hired to be deployed into animal rights, ‘ought to have been’ told about the risk of arrest and what to do. But he claims he can’t remember ‘minutiae’ such as whether he actually did tell them.

He confirms that the arresting officers would not be made aware that they had an undercover police officer in custody. He explains that if the spycops’ identities were disclosed they would need to be withdrawn from the field, at huge expense to the police. Never mind perverting the course of justice, think about the money.

If an officer came to court, MacLeod said he thinks the court should be informed of the spycops’ real identity. He clarifies that he thinks a court is more likely to keep the truth secret, whereas uniformed police are more likely to give the identity away. Not a lot of faith in his uniformed colleagues, there.

SPYCOP JOHN DINES ARRESTED

We’re shown a report of 14 March 1989, after MacLeod had returned to C Squad, which he signed off [MPS-0526792].

SDS officer John Dines was one of a group of people arrested in December 1988 at a protest outside a poultry processing plant in Hereford. They were all released without charge, and a number of them brought a complaint against the police for wrongful arrest.

The report says:

‘It is Detective Sergeant Dines’s intention to keep the details surrounding the incident sufficiently vague as to reduce the likelihood of further action against the West Mercia Constabulary.’

There then followed another MacLeod flip-flop.

Q: Would that course of action, if followed by John Dines, not have had the effect at least potentially of frustrating a legitimate complaint against the arresting force?

MacLeod: No, I am not sure.

Then, after one minute of being shown that it was a document he was involved with and signed, he reversed his opinion:

Q: Does it trouble you at all that an SDS officer was being advised to take a course of action which could have the effect of thwarting a legitimate complaint against the police?

MacLeod: Yes, I think it would, yes. Yes. I have to agree with that.

SPYCOP BOB LAMBERT’S ARREST

We’re shown a report dated March 1987 [MPS-0526789] about another specific arrest, one which happened while MacLeod was in charge of the SDS. Bob Lambert was arrested hunt saboteuring in Crawley on 28 February 1987. The report is written by Docker, who had gone along on the day seemingly in readiness for Lambert’s arrest.

MacLeod claims he doesn’t remember it, but says ‘there is always a risk of a fracas occurring’ with hunt sabs.

He is yet another cop who sees hunt sabs as instigators of violence. But Docker’s report of the day describes how the sabs came across a police roadblock, and decamped into fields. They were all chased and arrested despite not having committed any crime:

‘However, it soon became apparent that most of those arrested (including Detective Sergeant Lambert) had not committed any substantive offence and therefore, after about two hours in police custody, Detective Sergeant Lambert was released without charge.’

Docker goes on to say that it was seen as being positive for Lambert:

‘Although the arrest of an SDS officer is always an unwelcome experience, I consider that, on this occasion, the matter has proved beneficial. Detective Sergeant Lambert’s standing within his group has been enhanced, further useful intelligence has been obtained and, above all, our operation has not been compromised in any way at all.’

It’s unclear whether this means that getting arrested was a premeditated plan for the day, or whether Docker is trying to spin a negative event as something good. It is perhaps the latter, as there’s no indication of what the ‘further useful intelligence’ might have been.

MacLeod agrees the arrest was good. He says that gathering intelligence was the top priority. Being arrested and deceiving uniformed officers was merely an ‘occupational hazard’.

He explains that, though arrest might bolster an officer’s standing in a group, he’s certain they should never get arrested deliberately.

Gargitter asks him about the dilemma faced by the spycops who tried to infiltrate the Animal Liberation Front (ALF). How could they possibly get close enough to criminals to gather useful intelligence about them unless they took part in crimes with them?

‘Well, from my recollection, and I am quite clear on this, they were aware of the provisions of agent provocateur and they would not be encouraged to take this one step further. It would be crossing the line between what’s acceptable and what is not.’

He’s saying they were told that it was OK to cross a first line of spontaneous public disorder and get arrested, but not a second line of premeditated criminal damage. It’s only 20 minutes since he told the Inquiry that he didn’t tell them this, couldn’t imagine how it would even have been possible to tell them, and that doing so would be ‘wet-nursing’ them.

He insists that he would never have encouraged spycops to commit criminal acts. He sees the quandary they were in, but says he expected the spycops to find a way around that, to somehow observe without taking part.

Gargitter points out that always standing by the sidelines of very secretive groups committing criminal acts probably means never actually getting to observe.

BOB LAMBERT IN THE ANIMAL LIBERATION FRONT

We moved on specifically to Lambert’s infiltration of an Animal Liberation Front cell and his part in placing timed incendiary devices in branches of Debenhams department store that sold fur.

In 2016, MacLeod was interviewed by Operation Sparkler, the internal police investigation into the Debenhams attacks. He told them that Lambert could not have known about the incendiary device incident in advance as there’s no way he could have got inside a small ALF cell:

‘It would be entirely out of character for him and it would carry an enormous risk with no conceivable benefit.’

Except that:

• it’s already established that Lambert had participated in crimes before this one

• there’s no way he could have got the intelligence he reported without being in the ALF cell

• the ‘conceivable benefit’ is that he supplied the kind of reports his bosses wanted to see, secured convictions for the incendiary devices, got a commendation, and was promoted

MacLeod is surely aware of all this.

MacLeod agrees that ALF cells were very secretive and didn’t share information with those outside. He claims that he never had any discussions with Lambert about how he would actually be able to obtain intelligence without being part of it.

Asked if he was ever concerned that Lambert was getting too involved, he was blunt:

‘No. His role, after all, is to obtain intelligence and to prevent crime.’

In his witness statement, he is clear about Lambert:

‘His tasking was precisely to insinuate himself as close as possible to the cell.’

What could this mean if not participating? MacLeod says it meant being popular and hearing about ALF plans in ‘casual conversations’. Gargitter points out what MacLeod had just said, that there was no casual talk with anyone outside the cells.

MacLeod agrees it was clear that Lambert was privy to what was said within the ALF cell, and that the ALF cells didn’t talk to outsiders, but still refuses to admit the obvious conclusion.

We see a 13 January 1993 document [MPS-0730597] which discusses the issue of participation in crime. This is several years after MacLeod left the SDS. It says:

‘The higher risk ‘fields’ for involvement in crime are anti-fascist activity, anarchism and animal rights. In the last mentioned field, in order to gain full acceptance and trust, participation in ‘illegal’ activities is essential.’

MacLeod is asked if he agreed with this when he was in charge. He waffles a lot about moral dilemmas and fine lines. He is asked the same question again and eventually says that yes, he would have agreed with it as a manager:

‘It’s the lesser of two evils.’

Gargitter gets him to specifically say that, although the document post-dates his time, in his era he held the same view. There are circumstances in which he would have balanced considerations and come to the conclusion that a spycop’s criminal activity was in fact essential:

‘Well, I have to stand by that. Yes.’

This is a few minutes after he said that officers were told never to do it, which in turn was a few minutes after he said it was impossible to tell officers never to do it. His contradictions are really stacking up on each other here.

The document lays out an escalating scale of criminal activities, from visiting premises without actually committing an offence, all the way up to arson and incendiary devices. MacLeod says he would draw the line at arson or a threat to life.

LAMBERT’S CRIMINAL DAMAGE

We next see a document [MPS-0742726] detailing how, on 28 November 1986 (just after MacLeod joined the SDS), a vehicle belonging to a director of vivisection company Biorex was damaged with paint-stripper in North London.

The Inquiry has heard that Lambert was responsible for this action. Might Lambert have been authorised to do this? MacLeod retorts:

‘He shouldn’t have been… Robert Lambert is well familiar with the law, and would know that that is going one step too far’

This is just after MacLeod had confirmed that property damage with no fire or threat to life was not, in fact, a step too far for spycops infiltrating animal rights campaigns. The contradiction is put to him and he replies:

‘It is indeed a very fine line, I accept that. No, this is acts of vandalism against property… I think we have to draw a line here. I think we draw the line at that.’

This is another flip-flop on whether it was justified to be involved in more serious crime. It seems clear that MacLeod thought it was justified at the time and still thinks so now, but knows that he shouldn’t admit that.

He desperately tries to add a few more layers of insulation between himself and accountability:

‘I wouldn’t have known about it. In fact, this is the first I have become aware of this. Of course it is outside my time period anyway.’

It’s pointed out that no, it actually was during the time when he was running the SDS.

INCENDIARY PLAN

The next report we see is dated 9 June 1987 [MPS-0740088], about secret meetings of ALF activists from across the UK. It says that the ALF plans to carry out attacks on London department stores which still sell fur. They will use timed incendiary devices to set off the shops’ sprinkler systems in the dead of night and cause damage by flooding. Lambert has told the Inquiry he was at one of the meetings in Manchester.

MacLeod says he is certain Lambert didn’t tell him about going, even though it’s the kind of thing he should have reported. Asked if it shows that Lambert was ‘inappropriately close’ to those who were planning these attacks, MacLeod once more washes his own hands of it and dodges condemnation of Lambert:

‘Field officers are expected to use their initiative. Once again, we have to allow a certain degree of latitude. They are mature officers, they know what they are doing.’

The irony of saying this in response to a question about Lambert not doing what he’s supposed to was apparently unintentional.

MacLeod starting waxing lyrical about Lambert again, about what a successful spycop he was, how he is a very intelligent man, full of common sense. It is pointed out that Lambert was deceptive towards Jacqui and the SDS, so perhaps his judgement on committing crimes was equally poor.

MacLeod is clear that pouring paint stripper on a car is far worse than sexually abusing women and having a son he knew he’d abandon when his deployment ended:

‘I am not sure you can compare the two. These are moral judgments only he can make. I don’t think we can conflate the two, between the illicit relationship with this lady and the planting of devices.’

Returning to Lambert’s report, it mentions the long custodial sentences meted out to those who’d been convicted of planting incendiary devices:

‘Accordingly, the use of incendiary devices is restricted to the most dedicated activists, who are forced to observe strict security even amongst their comrades in the animal rights movement. Such activists always pay due regard to the prospect of surveillance and infiltration even though they may not always be expert at countering it.’

MacLeod says he never knew about any of this.

The report is dated 9 June 1987. The incendiary devices in Debenhams stores went off on the night of 11 July 1987. The Inquiry has not been able to find any further reporting from Lambert in the intervening five weeks, even though he was spying on an active ALF cell about to plant devices.

WHY AREN’T THERE ANY REPORTS?

MacLeod says that Lambert was a ‘prolific reporter’, but claims that he never noticed at the time that Lambert had suddenly stopped producing any reports at all for more than a month before the Debenhams attacks.

He’s not the first of Lambert’s managers to make this claim. Perhaps we believe that they wouldn’t notice Lambert just stopping his reporting for five weeks straight. Or perhaps they’re lying and they either agreed to him not giving written reports because they didn’t want a paper trail about what he was doing, or else he made reports but they’ve been destroyed.

In his witness statement, MacLeod said:

‘There were no changes in the pattern and focus of Lambert’s reporting in the six months preceding the Debenhams attack such that I had reason to doubt whether he was reporting all of the information/intelligence that he obtained during this period.

I would point out that in paragraph 6 of his report dated 9 June 1987 he promises to report any planned attacks. I would have had faith that he would do so.’

This indeed sounds a lot like there were reports but they’ve subsequently gone missing, or else there were reports only made orally.

MacLeod’s witness statement also says that ‘hot intelligence’ shared by Lambert in one-to-one meetings with the managers would ‘most certainly have been documented’. Lambert, on the other hand, claims he had lots of his conversations with spycops managers in the five-week period, and much of the content did not result in any kind of written report.

MacLeod says he doesn’t remember that. However, he has no suggestion as to why there’s a huge gap in reporting at such a key time. He specifically rejects Eric Docker’s claim that Lambert was simply so busy for five weeks that he didn’t have time to make any reports.

In his statement, MacLeod said he was not surprised to learn that during this period Lambert had regular outdoor meetings with Geoff Sheppard, a fellow member of the ALF cell. Surely that shows Lambert was part of the cell. MacLeod halfway agrees:

‘He was certainly close to the centre.’