UCPI Daily Report, 11 May 2022

Tranche 1, Phase 3, Day 3

11 May 2022

The third day of the 2022 Undercover Policing Inquiry hearings concerning the management of the Special Demonstration Squad 1968-82 included opening statements from:

The third day of the 2022 Undercover Policing Inquiry hearings concerning the management of the Special Demonstration Squad 1968-82 included opening statements from:

Rajiv Menon QC (representing Tariq Ali, Piers Corbyn and Ernie Tate)

Dave Morris (activist, Inquiry core participant)

Kirsten Heaven (representing Other Non-Police, Non-State Core Participants [through the co-ordinating group])

Summary of Evidence of ‘Madeleine’ and Julia Poynter

Rajiv Menon QC (representing Tariq Ali, Piers Corbyn and the interests of Ernie Tate)

NB: Ernie Tate sadly passed away in 2021, without receiving any meaningful disclosure from the Inquiry.

SECRET HEARINGS AND MASSIVE REDACTIONS

Rajiv Menon QC

First of all, Mr Menon spoke about the secret hearings that have been held during the last year, known as the ‘T1P4 hearings’. In his view, it is “fundamentally wrong and unfair” to conduct closed hearings as part of a so-called ‘Public Inquiry’.

The transcripts of those hearings have been heavily redacted, and we are told that this is being done “in the public interest”. Evidence was taken from five officers in T1P4, but we are not being told their real or cover names. Instead of being supplied with copies of their evidence, we have a document of ‘Unattributed Excerpts‘.

This was especially ridiculous in the case of officer HN21:

“an officer who was perfectly willing 20 years ago to speak openly about his undercover role in the BBC documentary True Spies, is unable to give evidence in open session to a Public Inquiry.”

This is someone who admitted having a sexual relationship with at least one woman, but we have not been permitted to question him or find out more about this.

It is estimated that 50% of the evidence gathered during T1P4 has been redacted, and might therefore remain secret forever. Menon repeated the request he made last year – that the Inquiry reconsider the need for such redactions, and commit to regularly reviewing decisions about disclosure, so that names and information can be made public in future if circumstances change.

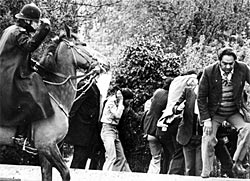

POLICE VIOLENCE

Mounted police intimidate protesters, Southall,, 23 April 1979 [Pic: John Sturrock]

HN41 says that he was warned by senior Special Branch officers not to go with his target group “because the uniform police were going to clamp down on the demonstrations” and “management considered the dangers were more than normal”.

Mr Menon states there is no doubt uniformed police were under secret orders to use violence at anti-fascist demonstrations. Meanwhile intelligence from the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) seemed to heighten a view within the police that all anti-fascist demonstrators were subversives so fair game for police truncheons.

POLITICAL BIAS

According to DI Angus McIntosh (officer HN244), there was a “high level policy decision” not to infiltrate extreme right-wing groups. This confirms what we already knew about the prejudiced nature of SDS surveillance. Yet, given HN41’s observations, who exactly made this decision and why?

Mr Menon asks us to bear in mind that the SDS was an integral part of the secret state. Senior offices and politicians were well aware of the SDS’ existence, something borne out by the disclosure we have had.

He also lets the comments of SDS manager Geoffrey Craft (officer HN34) about “mob rule”, “lefties” and “scruffy, hairy so-and-so’s” speak for themselves, having described it as “classic ‘Reds under the Bed’ stuff with a dose of McCarthyism thrown in for good measure” [Inquiry document number MPS-0747446, not yet published on the Inquiry website].

GOOD – FOR NOTHING?

Following up on his earlier points on HN41, he addresses the claimed success of SDS in combating public disorder by asking:

“Are Red Lion Square, Grunwick, Lewisham and Southall supposed to be police ‘successes’? If so, perhaps this gives the measure of what the police were trying to achieve at the time”.

Really “scraping the justification barrel” is the suggestion that the unit’s usefulness includes working out that some groups pose no threat at all, by infiltrating them for long periods of time (which we see in many of the SDS Annual Reports).

ALTERNATIVE INTELLIGENCE GATHERING METHODS

He next looked at whether there were less harmful ways of collecting intelligence, using the case of SDS officer Roy Creamer and the anarchist scene of the late 60s/ early 70s. DI Creamer was described by noted anarchist Stuart Christie as “the Yard’s dialectician of dissent.”

Creamer was curious as to what made anarchists tick. He was the epitome of what Menon called the ‘direct approach’, as opposed to the ‘oblique approach’ developed by Conrad Dixon and the other spycops.

Instead of going undercover, he established friendly relationships with targets and talked to them. The barrister suggested the ‘direct approach’ was a proportionate and less damaging approach to the gathering of intelligence than the SDS method.

However, we at the Campaign Opposing Police Surveillance strongly recommend you never talk to coppers, especially if they seem friendly!

SDS & MI5

Menon next moved to a theme of increasing importance in the Inquiry – the relationship between the SDS and the Security Service (aka MI5) [see Inquiry document MPS-0747446 when they upload it to the Inquiry site].

He emphasised the Security Service’s interest in this new unit from the moment it was founded. They recognised the Squad’s potential value as a long-term intelligence gathering operation against all those it deemed ‘subversive’. If anything;

“MI5 were the organ grinders, and SDS were the monkeys. Only the monkeys did not know to whose tune they were really dancing.”

Even Craft says that: “the Branch were the legs of the Security Service… SDS was only a development of that”, and that the SDS provided the Security Service with “a huge base of information for their vetting activity”.

Opening statement of Rajiv Menon QC

Dave Morris (representing himself)

This was a relatively short statement from Morris, who has already given several previous opening statements to the Inquiry and a witness statement.

His name appears in multiple SDS reports released by the Inquiry. He was active in various anarchist and environmental groups:

“I have been involved since 1974 in a range of groups and campaigns trying to encourage the public to support one another and empower themselves where they live and work, to challenge injustice, oppression and damage to the environment, and to make the world a better place for everyone.

“The various groups I have been involved in over the decades have been open and collectively-run, and engaged in the kind of public activities which the public are invited to join in or to replicate for themselves, and which are essential if humanity is to progress and survive.”

These groups challenged the government and powerful companies, as well as ruthless and unaccountable elites which were ‘subversive of society and people’s real needs.’

Morris said:

“I am proud of the many groups and campaigns I have been involved in and believe that such efforts should be supported, not undermined.”

One of those campaigns which is now known to have been infiltrated was the Torness Alliance anti-nuclear campaign.

Having noted that the Inquiry’s Chair, Sir John Mitting, had been furnished with an education in Trotskyism from Tariq Ali, Morris correspondingly provided Mitting with a primer on anarchism, explaining that some institutions simply cannot be reformed but must be replaced by genuine democracy.

He helpfully provided a list of books for the Chair to read in order to better understand anarchist thinking:

Anarchism – A Very Short Introduction by Colin Ward

Demanding the Impossible by Peter Marshall

On Anarchism by Noam Chomsky

and just in case Mitting was partial to science fiction, Ursula Le Guin’s classic The Dispossessed.

Morris mentioned one spycop, ‘Tony Williams’ (officer HN20), who became treasurer and secretary of the London Workers Group and whose reporting was no doubt passed on to the Security Service for blacklisting purposes. Apparently the SDS told the Security Service they considered Williams’ withdrawal from the field ‘no great loss’ as he had not been ‘particularly productive’.

Morris mentioned one spycop, ‘Tony Williams’ (officer HN20), who became treasurer and secretary of the London Workers Group and whose reporting was no doubt passed on to the Security Service for blacklisting purposes. Apparently the SDS told the Security Service they considered Williams’ withdrawal from the field ‘no great loss’ as he had not been ‘particularly productive’.

Morris criticised the Inquiry for continued delays and other problems to do with the publication of documents – some of which were released so late in the day that there was insufficient time for anyone to process them properly.

Morris was particularly critical of the police and the Inquiry for failing to prioritise the welfare of the spycops’ victims. He made the point that those undercover officers had a duty of care towards the public. The police’s sudden championing of privacy and human rights, when it came to applying for anonymity, was hypocritical and self-serving, and only because they themselves were now being exposed to public scrutiny.

Finally, in a slightly surreal moment, Mitting asked Morris which book he would select from his list if he could only pick one. Dave unhesitantly went for Peter Marshall’s Demanding the Impossible, although he warned that it was a “weighty tome”.

Opening statement of Dave Morris

Kirsten Heaven (representing the ‘Non State Non Police Core Participants, through the coordinating group’)

In previous hearings we heard shocking evidence of what Heaven described as “an unjustifiable, unlawful, and profoundly anti-democratic system of surveillance that was fundamentally flawed”.

Managers are now in the spotlight to answer for that regime. However:

“The witness statements disclosed in this Inquiry contain a litany of denials and an apparent unwillingness to accept responsibility or admit knowledge on key decision making and events. The managers appear reluctant to give a full and honest explanation of why things went so badly wrong within the SDS in the Tranche 1 era (1968-1982), and beyond.”

Basically, if they retain a sense of loyalty to the police, it is deeply misplaced, Heaven said, referring to the recent appalling exposures:

“This is an institution which has been found to be institutionally racist, institutionally corrupt and marred by a culture of toxic masculinity, homophobia, misogyny, and sexual harassment.”

OVERSIGHT

These managers emphasised to their funders at the Home Office how robust their supervision of the undercovers was. Yet there was no code of conduct or formal training.

“Did the managers conceal these practices from their political masters or was it – as the non-state co-operating group suspect – that the cover-up went to the highest political level?”

In order to understand the problems of the SDS we must understand who controlled the unit, and the extent to which the SDS was being directed by the likes of other parts of Special Branch and the Security Service, referred to as the ‘customers’.

Worryingly, there is disclosed evidence that although they were aware of the problems, the Home Office and senior police officers all turned a blind eye. This meant there was no effective external oversight of the SDS, or of wider Special Branch.

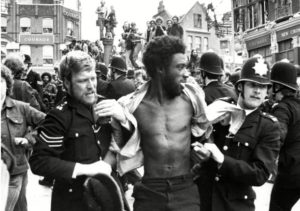

Police detain man, Lewisham, 13 August1977

Additionally, both the Home Office and the Security Service knew that the SDS activities of the time were unlawful. This was the reason for shrouding it in secrecy, a secrecy that allowed the abuses to flourish.

As raised in other Opening Statements, a problematic definition of ‘subversion’ was used to justify reporting on pretty much anything and anyone. The Security Service was able to exercise its influence over the affairs of Special Branch to shape how the unit operated.

Senior police officers were willing to go along with this, and ignore the lack of public order benefits of these deployments. Claims that the SDS benefited and improved the police’s attitudes to public order simply don’t stand up. Heaven used the events of Red Lion Square, Southall and Lewisham as examples. The Brixton riots of 1981 demonstrated just how useless the unit when it came to predicting or preventing public disorder.

There was no real attempt to evaluate the usefulness of the unit more generally. Annual Reports were written up in order to justify its existence and ongoing funding. It was the duty of the managers “to consider the threat to freedom of speech and democratic principles posed by the SDS”, and they failed to do this.

MANAGEMENT OF THE SDS

Heaven noted that the SDS was managed loosely and wonders whether the early ‘free and easy’ style became the blueprint for the future. Despite claims of close supervision, the managers remained blind to the various sexual relationships, and the sexist banter, of these officers.

As to the standardisation of the lengths of deployments to four years, she wants to know if there was a “positive and considered managerial decision to extend all deployments well beyond twelve months”, adding:

“It is not rocket science that the longer a UCO [undercover officer] is deployed, the greater chance there is of collateral intrusion, the development of close personal ties, sexual and intimate relationships, misconduct and abuse of power and trust”.

The lack of training given to both undercover officers and their managers is concerning. The Inquiry must look at what basic police training was at the time to understand how much they knew about legal principles such as entering private property without a search warrant or conduct issues such as sexual relationships while on duty. How did the managers reconcile this with the activities of the SDS?

DODGY REPORTING

As previously evidenced, there is much reporting which is distressing and inappropriate, peppered as it is with racism and misogyny. Nobody pointed it out at the time. The SDS managers all now say that these reports were produced for others to comment on, evaluate and use.

However, these senior officers were responsible for the unit’s work, and as such have a duty to explain this reporting along with the other practices that took place under their watch.

CONCLUSION

The SDS, as an operation, was never lawful. These abuses were aided by the Home Office sanctioning and maintaining the unit’s secretive existence, leading to a “catastrophic failure of policing at the heart of British democracy”.

The way that the unit acted during this period (1968-1982) paved the way for the abuses committed later – we were told that their “abhorrent practices survived and even flourished following legal reforms.”

Opening statement of Kirsten Heaven

‘Madeleine’ and Julia Poynter: Written statements

These written statements, from two ‘civilian witnesses’, were published in full today. The Inquiry prepared a short summary of each, and read it out loud. We prepared our own, below:

‘Madeleine’

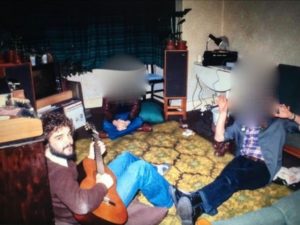

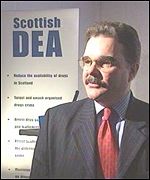

Special Demonstration Squad officer Vince Harvey during his deployment

‘Madeleine’ was deceived into a relationship with an undercover officer known as ‘Vince Miller’ (officer HN354), who infiltrated the Walthamstow branch of the Socialist Workers Party (1976 -1979). Since then Vince’s real surname (Harvey) has been released.

It turns out that he reached the level of Superintendent before retiring from the police, and went on to a top job, National Director at the National Criminal Intelligence Service. The Undercover Research Group have published a summary of Vincent Harvey’s post-undercover career.

(‘Madeleine’ had already provided the Inquiry with a written statement in February 2021, and gave compelling evidence in hearings of May 2021. Also see Charlotte Killroy QC’s statement on her behalf this week)

COLD AND CYNICAL TACTICS

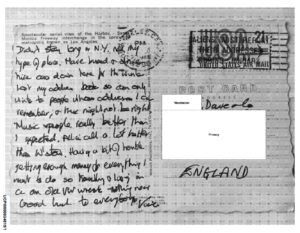

Vince Miller’s postcard to Madeleine, 1979

In her statement, ‘Madeleine’ recounted the stressful and “excruciating” nature of her live witness testimony at the Inquiry in May 2021, where she suffered “intrusive questioning”.

This was so bad that other women from ‘Category H’ suffered “such significant distress that they were unsure if they would be able to continue their participation in the Inquiry”. This raises serious questions about the treatment of witnesses, who are in effect sexual abuse survivors.

‘Madeleine’ mentioned Vince sending her a postcard at the end of 1979, after he disappeared from her life, giving her false hope about him. She now knows that this was “a cold and cynical tactic”, perpetuated on other women by other undercovers who’d disappeared in similar ways.

MANIPULATED BY THE INQUIRY

She then recounted how she’d generously acceded to the Inquiry’s request not to demand Harvey’s real name, in order to ‘protect’ one of his family members.

However, she then found out more about his long career in policing, which involved many public appearances. She was shocked to learn that while Harvey was its Director, the National Criminal Intelligence Service had responsibility for the Animal Rights National Index (a forerunner of another undercover political policing unit, the National Public Order Intelligence Unit) and the National Domestic Extremism Database:

“I think it is imperative that he is required to provide evidence relating to this role in later tranches.”

Perhaps most disturbing for ‘Madeleine’ was the revelation that Harvey had been in charge of a child sexual abuse investigation, Operation Pragada, saying she felt “physically sick” and “turned her stomach” on finding this out.

‘Madeleine’ now feels manipulated into the decision she made not to demand his real name. The Inquiry would have known about his later senior policing roles. It is a disgrace that they allowed this to happen.

INCOMPLETE RECORD OF REPORTING ON ‘MADELEINE’

Former SDS officer Vince Harvey, 1999

Madeleine has always maintained that the 23 Special Branch reports in her witness pack could not be a complete record of the reporting on her.

Having now come across a report of a meeting that took place at her home, but did not mention her name, she believes that Harvey purposefully omitted her name from the list, due to his involvement with her.

‘Madeleine’ now wants to check all 175 reports produced by Harvey – which the Inquiry has chosen not to publish – to see if they refer to events that she attended with him. All reports thought to have been authored by this officer should be disclosed.

Opening statement of ‘Madeleine’

Julia Poynter

Julia is also a former member of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP), and knew both ‘Madeleine’ and ‘Vince Miller’ back in the day. She has come forward and was able to collaborate her old comrade’s accounts of the time. Poynter also knew ‘Phil Cooper’ (officer HN155) who infiltrated the SWP (1979-84) after ‘Vince Miller’ had ended his deployment.

Poynter was shocked that the Inquiry held 62 reports which mentioned her name. She described her political trajectory, going from being a disillusioned Labour Party member to joining the SWP in 1975, where her “main focus was anti-racism work through my involvement with the Anti Nazi League”.

MISSED OPPORTUNITY

Poynter says that when she attended a Trade Union Conference on Undercover Policing in November 2019, she saw ‘Vince Miller’s name on a document listing all the undercovers, but did not connect this with the man she knew. If only the Inquiry had released a photo at that time, she would have been able to identify him:

“I could then have provided this evidence to the Inquiry at a much earlier date.”

Two years later, listening to the 2021 hearings, Julia realised that ‘Madeleine’ was an old friend of hers, who she had not seen for many years. She was shocked that Harvey was still maintaining that this had only been a one-night stand:

“It was clear to me at the time that it had been a significant relationship for her.”

‘PHIL COOPER’

Poynter went on to discuss her interactions with ‘Phil Cooper’, who she met through her boyfriend. Cooper and her then-partner set up Waltham Forest Anti Nuclear Campaign (WFANC) in about 1980. Cooper said in his written statement that he had not formed any significant friendships in the group.

However, Poynter recalls that:

“[her boyfriend] and Phil got on very well and were good friends. WFANC would meet at our house and Phil would attend those meetings. My memory of Phil is that he was a real laugh, very much into drinking and having a good time.”

Cooper drank heavily, and smoked weed regularly. On one occasion, she says he was so inebriated that he fell off his chair and broke it.

Poynter addressed many of the Special Branch Reports which mentioned her name. One such report describes a 1981 SWP branch meeting – a fireman contact has offered to help carry out a personal investigation, following a spate of racist attacks on Asians in the area.

According to the report:

“The SWP intend to use this information to stir up further unrest within the Asian community in Walthamstow.”

She does not accept this cynical interpretation – what’s been left out of the report is what had actually happened – in early July petrol had been poured through the door of an Asian household in the area, killing Parveen Khan (28) and her children Kamran (11), Aqsa (10) and Imran (2). She stated:

“The community were rightfully angry and we were reaching out and helping to build alliances in the community. It is offensive that the police were spying on us carrying out this work rather than spending resources identifying the murderers, who as far as I am aware have never been caught.”

Opening statement of Julia Poynter

Transcript of the full day’s hearing

The current round of Undercover Policing Inquiry hearings, focusing on Special Demonstration Squad managers 1968-82, continue until Friday 20 May.

Good on you all for keeping us up to date . Your doing great work.