UCPI: Weekly Report 4: 21-23 April 2021

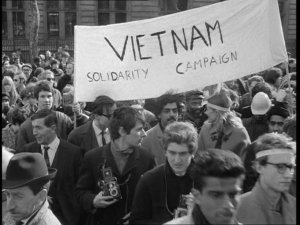

On 21 April 2021, Tranche 1, Phase 2 of the Undercover Policing Inquiry (UCPI) began. It will last for just over three weeks, examining the actions of the Metropolitan Police’s undercover political unit, the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS), from 1973-82. Subsequent hearings will look at the unit’s later years.

This report summarises the main points of the first three days. For more details, see our daily reports: Day 1: 21 April, Day 2: 22 April, and Day 3: 23 April. For background information on the Inquiry, see our UCPI FAQ.

ABUSE WAS THE PURPOSE

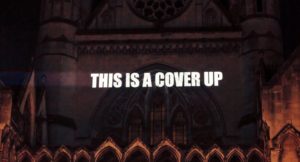

In stark contrast to previous claims of it all being the fault of ‘rogue officers’, then ‘rogue units’, the vintage evidence newly released by the Inquiry for these hearings confirms clear knowledge of SDS operations and tactics within the Metropolitan Police, MI5, and to the highest level of the Home Office.

These operations included:

- deliberately deceiving activists and other women into forming intimate sexual relationships with them

- stealing the identities of dead children to create their undercover identities

- rising to the highest levels of the groups they infiltrated, directly influencing and undermining those groups

SDS Annual Reports always included a list of groups targeted during the year. Apart from one officer spying on the far right (and only because the left-wing group he was infiltrating asked him to do so), all the groups are on what can broadly be seen as the left: communist, socialist, anti-nuclear, Irish liberation, women’s rights.

As with the opening day of the November hearings, some previously unmentioned groups were named as having been spied upon. And as before, this information comes too late to be of use to people who were legitimate members of those groups.

The Counsel to the Inquiry questions witnesses (unlike a trial with different lawyers pressurising witnesses from different directions). It is immediately apparent that, of the many witnesses who should be called, only a fraction has actually been invited.

This is directly owing to the police, who have delayed the Inquiry for so long that many of those who should be giving evidence are now either too frail, or actually deceased. The latter includes two Home Secretaries and three Met Commissioners who have died since the Inquiry was announced in 2014, as well as numerous senior officers who rose through the ranks from the SDS, plus four of the 22 officers whose cover names have been made public.

JUSTICE DELAYED

Delays and loss of witnesses have also been caused by the Inquiry itself, who have failed to contact or even try to find those who were spied upon, despite having their names, and have refused to provide cover names or photos of those who did the spying, which means their victims don’t get the chance to identify them and come forward. They even refused offers from spied-upon Core Participants to provide photos of undercover officers, and never thought to ask the officers themselves.

The delays continue to mount up. ‘Tranche 1 Phase 3’ hearings – dealing with the unit’s early managers from the SDS’s foundation in 1968 until 1982 – were scheduled to take place in October 2021, but have now been put back to the first half of 2022.

The Inquiry no longer expects to look at ‘Tranche 2’ (covering the years 1983-1992) next year – now to be dealt with in 2023 at the earliest the soonest.

This means a potential wait until 2024 for Tranche 3 (covering the SDS in 1993-2007), and even longer for Tranche 4, covering the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (1999-2011), which deployed the likes of Mark Kennedy.

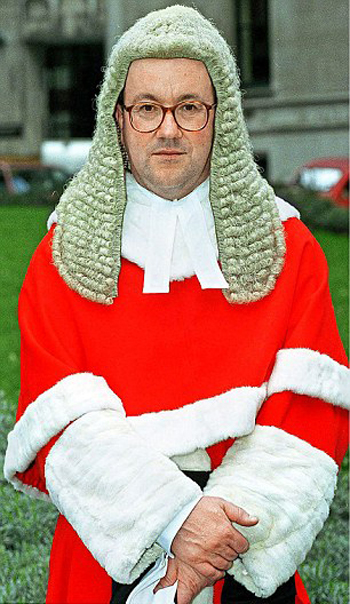

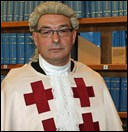

Sir John Mitting

The main cause of delay in this Inquiry has been the excessive demands for redactions made by the police and State bodies. Kirsten Heaven, representing some of the Non-Police, Non-State Core Participants (ie, those who were victims of SDS tactics)spoke of their anger and frustration at these new delays. She reminded the Chair, Sir John Mitting, that his predecessor Lord Pitchford, original Chair of the Inquiry, had intended to conclude in 2018.

Mitting responded that delays are inevitable and the most recent ones have been caused by providing documents to a new core participant, a member of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP), who is to give a witness statement. Mitting says there is so much vintage police material on the SWP that this cannot be done by October.

Ironically, existing Core Participants were meant to get police documents for the current hearings in mid-March 2021, but another 2000+ pages were added in April, only a couple of weeks before these hearings began, and people were expected to be able to read and respond to it.

The Inquiry needs the help of those who were spied on and, on a more personal level, those people have already waited too long for answers. They must be given full disclosure of documents relevant to them with plenty of time to analyse and reply so they can expose the lies. People should be given the files that mention them immediately The Met have said they’re happy to do this, if the Inquiry decrees it. Mitting has stated that that ‘perhaps the request cannot be fulfilled’. He gave no reason at all as to why this might be.

As for the new SWP Core Participant, the Inquiry made no attempt to contact her until recently, and this is not the only time this has happened.

A pattern is emerging of the Inquiry failing to contact Non-Police, Non-State Core Participants about evidence that involves them, and failing to ask state and police core participants for evidence in a timely manner.

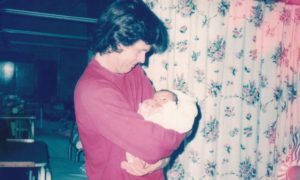

Last week we learned that spycop ‘Alan Bond‘ (HN67, 1981-86) may well have fathered a child while undercover, but is now said to be too ill to give evidence. The Inquiry has known of his condition for three years yet has not taken a statement from him.

Heaven recommended that the Inquiry prioritise collecting statements from all former officers and managers, and provide a full list of all Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) managers from 1968-82 who are due to give evidence in Phase 3, along with regular updates on their state of health.

EXCLUDING THE VICTIMS

Two of the many women who were targeted and spied on gave evidence this week. Diane Langford was a founding member of the Women’s Liberation Front during the time this phase of the hearings covers, and has been an activist for over 50 years. ‘Madeleine’ was an active member of the Socialist Workers Party from her teens onwards, and was spied upon and deceived into a sexual relationship with a spycop.

Diane Langford has only recently become a Core Participant at the Inquiry, thanks to the work of the Undercover Research Group. Her name appeared unredacted in many SDS reports disclosed at the previous round of hearings in November 2020, but the Inquiry only reached out to her just beforehand.

By the time she knew that ‘Sandra Davies’ – who had spied on her and voted to oust her as the leader of the group she had founded – was giving evidence to the Inquiry it was too late to book a place at the limited screening venue.

The Inquiry failed to ask Langford to give evidence, or tell her that she could seek legal representation. It’s not just about her own inclusion but, as she said:

‘how many others who were spied on are completely unaware that their names appear in these files?’

The Inquiry only contacted ‘Madeleine’ in February 2020, yet she was known about in 2017, when the Inquiry first dealt with the spycop who abused her, ‘Vince Miller‘ (HN354, 1976-79). They reneged on promises to send a female officer to bring her the news and put her touch with Police Spies Out of Lives, a group which represents and supports women deceived into relationships by spycops.

Rajiv Menon QC, representing Piers Corbyn, made some excellent points about the Inquiry’s insistence on secrecy:

- Out of an estimated 18 surviving SDS officers deployed during 1973-82 whose cover names have been disclosed, only eight are being called to give evidence. This was a critical period in the history of the SDS. We should be hearing from as many spycops as possible.

- Evidence from seven SDS officers whose real and cover names have been restricted is not being disclosed. Instead, it is redacted, edited and amalgamated into an eight page ‘gist’. We need to know what they did individually, if their information is to be of any use at all.

- Most frustrating is the redaction of the names of 130 groups spied on and infiltrated by the SDS between 1969 and 1984. Why, 35-50 years later, must these remain secret, at the insistence of those who did the spying? It’s a betrayal of the purpose of the Inquiry.

After the public hearings are finished in mid-May, the following three weeks will be taken up with spycops giving evidence in secret. At least one of them appeared in the BBC’s True Spies documentary talking about his career, so it is unclear why he cannot give public evidence to the Inquiry.

WHO WAS SPIED UPON, AND WHY?

The newly disclosed documents show that the decision of who was targeted by the spycops came either straight from the top (MI5 and the Home Office) or straight from the bottom (the spycops deciding for themselves). In both cases, it was left-wing, equality, and social justice campaigns which were infiltrated and undermined. There is only one exception to this.

‘Peter Collins‘ (HN303, 1973-77), infiltrated the Workers Revolutionary Party. Not knowing he was a spy, they asked him, in turn, to infiltrate a breakaway group of the far-right National Front. This is bragged about in the 1974 SDS report, showing a total lack of awareness that their only foray into the far-right was instigated by a left-wing group and done to maintain cover.

SEEING THINGS IN CONTEXT

Police lawyers insisted that the actions of the SDS be seen in the historical context of the period and judged by those standards.

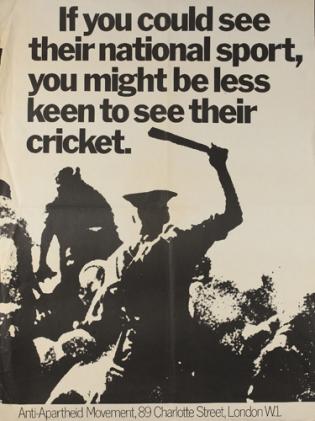

Very well then: the 1970s saw the rise of many campaigns, which attempted to improve the lives of all those in society and are now seen as mainstream, such as women’s rights and anti-racism groups.

Simultaneously, the far-right and fascist groups such as the National Front and Column 88 were on the rise.

According to the police’s lawyers, the spycops were politically neutral and did not target one kind of group over another. This is a ridiculous claim given that hundreds of groups and individuals perceived to be on ‘the left’ were targeted, while the far-right, who created fear through their use of violence, were not policed in the same way.

In fact, the SDS Annual Reports consistently downplayed the threat posed by the far-right. The police’s lawyers suggested there was no need to infiltrate groups like the National Front, because they ‘tended to cooperate’ with Special Branch.

At this time, Column 88 were threatening to burn down the homes of SWP members. The National Front were attacking Bengalis in Brick Lane, smashing up reggae record shops and vandalising mosques. There was firebombing and murder.

Instead of investigating the racist firebombing that killed 13 young black people in New Cross, the SDS were reporting on school children and providing MI5 with copies of Socialist Workers Party babysitting rotas.

As Diane Langford said:

‘To read these reports is to see some of the greatest ideas of our time crushed into the narrow confines of a mentality absolutely lacking in the capacity to comprehend them’

WOMEN AND CHILDREN

Many of the reports on the SWP have photographs of children attached. These were either the children of Socialist Workers Party members, or children who were engaged enough with their society to be part of the School Kids Against the Nazis. Reporting on children was a new development for the SDS, but then happened frequently.

One report, signed off by very senior officers and copied to MI5, included details about someone’s brother and his wife, and contained a line about the couple having a ‘mongol child’, a derogatory term for someone with Down’s Syndrome.

Another, attributed to ‘Barry Tompkins‘ (HN106, 1979-83), includes details of a woman activist who had an abortion, and speculation about ‘the putative father’. This kind of invasion of privacy cannot be justified.

The Women’s Liberation Front was targeted, with reports detailing such subversive events as jumble sales and a children’s Christmas party.

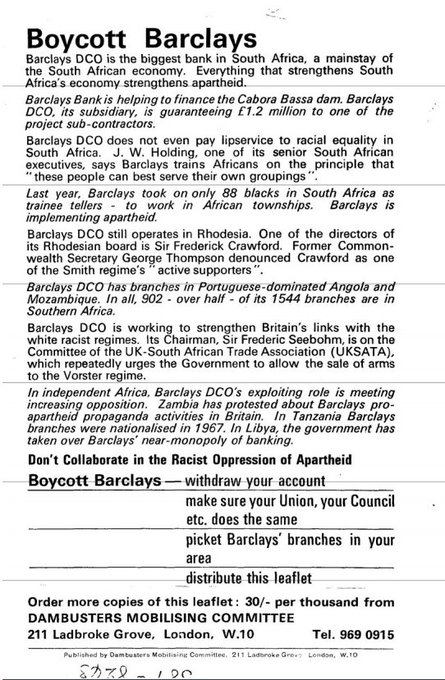

The youth wing of the Liberal Party was targeted by ‘Michael Scott‘ (HN298, 1971-76) in order to gather intelligence about anti-apartheid activist Peter Hain. The spycops cynically targeted all sorts of non-radical groups, displaying an utter contempt for civil society. Despite this, the 1975 SDS Annual Report claims that officers ‘concentrated on gathering intelligence about the activities of those extremists whose political views are to the left of the Communist Party of Great Britain’.

‘Madeleine’ wonders whether her father, a double war hero who fought fascism all his life, would also have been considered a ‘subversive’ and a ‘dangerous extremist’.

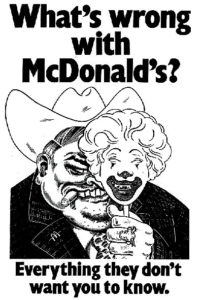

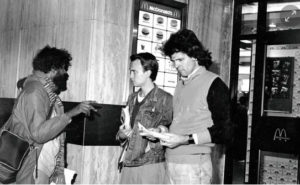

Dave Morris, one of the two defendants in the McLibel trial and spied upon by multiple officers, described his activism:

‘The essence of my personal motivation and political beliefs has remained constant throughout the last 50 years or so – the desire to tackle injustice, to seek improvements in society in the public interest, and to encourage and empower people to have as much control over their lives as possible.’

He confirms that judging by the standards of the time, as requested, a proper risk assessment of threats to society would have set its sights on other dangers – not just the far-right but fossil fuel companies, tobacco companies and car manufacturers.

ANTI-APARTHEID CAMPAIGNS & RACISM

One of those dangers would have been the South African State’s security service that was active in London in the 1970s, targeting the African National Congress and Anti-Apartheid Movement.

Bombings and murders were committed against anti-apartheid campaigners in Britain. Military materials were used. Few charges were ever brought. In 1972, Peter Hain received a letter bomb, opened by his 14-year-old sister. The incident remains uninvestigated. The spycops seem to have been wholly uninterested in pro-apartheid violence. Instead, they obsessively collected information on a wide range of left-wing groups that opposed it.

Racism was a huge issue in this era. There were violent confrontations. SDS officers were involved in the fascist rally and anti-fascist counter-protest, known as the ‘Battle of Lewisham’, in August 1977.

THE BATTLE OF LEWISHAM

Battle of Lewisham plaque, unveiled in 2017

The Inquiry were shown a BBC film and an Associated Press report on the ‘Battle of Lewisham’. The SDS Annual Report for that year suggested that this was a triumph of SDS intelligence, minimising the clashes and violence.

Even just these film clips, and the fact that the demo is now known as the Battle of Lewisham, makes this claim of negligible disorder laughable, and casts doubt about the accuracy of the other information in these Annual Reports.

It was mentioned that one SDS officer complained that the intelligence supplied in the run-up was ignored by police planning for the demo.

‘Madeleine’ emphatically refutes a claim made by spycop Vince Miller – and repeated in the SDS Annual Report that year – that bricks were stockpiled at various locations by the SWP along the planned NF route and that members of the SWP carried weapons to the march in bags. The police were, in reality, undermining efforts to fight fascism and combat racism.

‘Madeleine’ continued:

‘The Battle of Lewisham is now rightly considered a watershed moment like Cable Street in the fight against fascism in this country. Unable to control the streets, the National Front went into decline and the event is now proudly remembered as the moment when the far right was again defeated. It is now commemorated by the local council and seen as a symbol of a community coming together to say yes to black and white unity and no to the forces of hate.’

In the early 1980s, East London Workers Against Racism – a subgroup of the Revolutionary Communist Party, which supported victims of racist attacks – was infiltrated by SDS officer ‘Barry Tompkins’. This meant that Tompkins reported on the victims of racist violence.

Spying on victims of racist violence and the groups supporting them is a pattern that endured, something we will see when we look at the 1990s and the spying on the family of Stephen Lawrence, Ricky Reel, and many others.

WOMEN’S LIBERATION GROUPS

Diane Langford knew of two that undercover officers spied on her. The Inquiry have now told her it had been six.

Her full statement is compelling, articulate, and moving. Here we summarise some of her main points.

As with many others, Langford’s commitment to the women’s liberation movement was fuelled by personal experience. She gave the example of how, when she was in her early twenties, her 19-year-old flatmate died from an illegal back street abortion:

‘The memory of her death remains vivid for me still, at the age of 79.’

She listed three dramatic events that spring to mind when recalling the period under scrutiny:

• Dave Robertson threatened my friend with violence when she outed him as an undercover.

• Robertson ignored an allegation of attempted rape at a meeting, instead focusing on my domestic arrangements and ridiculing my partner

• Banner Books was burned down by fascists while undercover officers had surveilled and had access to the building, and a man was reported to have died. This needs investigating.

When told that ‘Sandra Davies’ (HN348, 1971-73) spied on 77 meetings, of which 55 were related to the women’s liberation movement, Langford responded:

‘Sounds like more than I did! Why is the women’s movement not a focus of the Inquiry? The Inquiry is colluding with the state to limit the search for evidence’.

Indeed, the list of groups that were spied on contains numerous women’s rights organisations, despite ‘Sandra Davies’ being the only female spycop deployed in this period – and only active from 1971-73.

The surveillance of the women in these groups by men, seemingly because women’s equality was viewed as a form of subversion, starkly illustrates the degree to which the SDS was institutionally sexist and abusive.

WOMEN DECEIVED INTO INTIMATE RELATIONSHIPS

The Inquiry has found no documents from this era (1973-82) that instruct spycops officers either to have or to abstain from sexual relationships. But managers indeed know about it. ‘Graham Coates’ (HN304, 1976-79) mentioned in his statement that he even heard comments and jokes about relationships from spycops at meetings with their managers.

During this time, all of the spycops (and their managers) were male. The SDS went these ten years without any women officers, which may well have had an influence of the unit’s culture. The vast majority of these men were married, which was noted at the time of recruitment. It was perhaps thought that this might deter the undercovers from getting too close to their targets, but clearly it didn’t prevent them initiating sexual relationships.

It is now clear that in the era being examined, numerous spycops had sexual relationships with women while using their undercover identities. Some of these women were the targets of their spying operations, others came into contact with the spycops socially.

To quote Langford again:

‘We see the callous use of women’s bodies by misogynous male officers who see such abuse as a perk of the job, and a confluence of the sexist behaviour and patriarchal attitudes of so-called left wing men in socialist groups and that of those spying on them.’

The practices and culture established in this period were the foundations of the long running sexism which infected the SDS. officers’ reports rate women’s attractiveness and comment on the size of their breasts. No account was taken of the impact of the officers’ behaviour on their wives and families.

NO NECESSITY FOR THESE RELATIONSHIPS

Spycops gave no thought to the dignity of women, to their right to choose who they had sex with, the risk of harm if they found out the truth, or what would happen if they got pregnant. Most officers involved readily admit there was no necessity for these relationships. It was gratuitous and a grossly intrusive invasion of private citizens’ lives. Any spycop who deceives someone into sex should forfeit their right to anonymity.

We were told in the past that these deceitful relationships only rarely occurred, but the evidence now being published provides a different picture. We now know that in the era examined by the current hearings, 1973-82, at least a third of the officers in the unit engaged in sexual relationships while undercover. Of these, ‘Jim Pickford‘ (HN300, 1974-76), and perhaps ‘Alan Bond‘ (HN67, 1981-86), had children with women they’d spied on.

Despite all these officer being known to have deceived women into relationships in this era, the Inquiry is only calling one, ‘Vince Miller‘ (HN354, 1976-79), to give evidence.

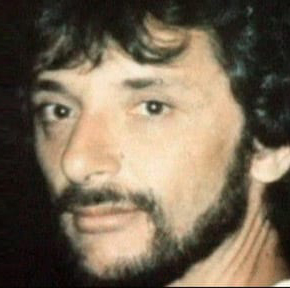

BLAIR PEACH

Blair Peach

An important issue in these hearings will be the killing of Blair Peach by the police in 1979, the subsequent police cover-up, and the campaign for justice by his then-partner Celia Stubbs. She has campaigned all her life, always to strengthen civil society, and was targeted by the undercovers as a result, even before Peach’s death. She recently spoke movingly about it, and spycops, to Channel 4 News.

The killing of Blair Peach and its cover-up remains one of the most notorious events in British police history, a national disgrace, and a permanent stain on the Met.

Peach and Stubbs were both members of the SWP as well as active anti-racist campaigners. Both Stubbs and Peach had spycops files kept on them, opened in 1974 and 1978, long before Peach was killed. The Inquiry has not released any of the documents involved that pre-date Peach’s death.

On 23 April 1979, there was a plan to march and sit down at Southall Town Hall protesting at a National Front meeting. Special Patrol Group (SPG) officers piled out of a van and one struck Peach, killing him. All six SPG officers refused to cooperate with the investigation that followed. And no officer was ever brought to justice for due to a major police cover-up.

The 1979 SDS Annual Report describes the Peach campaign as a main focus, yet the Inquiry has disclosed suspiciously few documents relating to this. The Home Office’s response in 1979 was to renew the SDS’s funding.

The SDS reported on the campaign for promoting actions like writing to MPs and local newspapers, and phoning in to radio shows. A number of spycops even attended Peach’s funeral, while police evidence gatherers photographed the attendees for later identification by the SDS.

Combined with the cover-up, it is clear that the infiltration of the Blair Peach campaign was about preventing guilty police officers from being held to account.

THE SPYING HASN’T STOPPED

Celia Stubbs, 2021

The spycops units have continued to take an active interest in the Blair Peach campaign ever since. A commemorative event was organised for the twentieth anniversary of his death in 1999, and this too was targeted by spycops, with the excuse that such campaigns were ‘anti-police’.

Police lawyers told the Inquiry last November that the SDS and NPIOU never directly targeted justice campaigns. But the documents we see in these hearings prove that is untrue. Officers were tasked to spy on the Peach campaign.

Celia Stubbs was also involved in the Hackney Community Defence Campaign and Colin Roach Centre, both of which were targeted by spycops. She is extremely disturbed about the fact that her lawyers were put under police surveillance, and Special Branch files were opened on them.

For Stubbs, this conspicuous lack of evidence is just one more obstruction to truth and accountability.

EMPLOYMENT BLACKLISTING

Many eyebrows were raised by the police lawyers’ insistence in their November Opening Statement that the SDS did not infiltrate trade unions and were not involved in blacklisting. The unit 1972 Annual Report contains references to trade union activity and strikes (the miners, the dockers and building workers), as well as the union-initiated Shrewsbury Two campaign.

The police lawyers tried to fend off the fact that SDS officers illegally supplied personal details of activists to employment blacklists. They claimed that police received material from sources beyond that as well, so we can’t be sure that what they called ‘so-called blacklisting’ definitely involved information from SDS officers.

The Information Commissioners Office (ICO) seized a blacklist of more than 3,200 people at the offices of construction industry blacklisters The Consulting Association in 2009. In 2012 the ICO’s investigations manager confirmed that there was information in the files that ‘could only be supplied by the police or the security services’.

In 2013, SDS whistleblower officer Peter Francis said that he believed information he’d reported when undercover in the 1990s had ended up in blacklist files.

Kirsten Heaven reminded the Inquiry that it was Operation Reuben, the Met’s own investigation, that found:

‘police, including Special Branches and the security services, supplied information to the blacklist funded by the country’s major construction firms, the Consulting Association and other agencies.’

According to the Independent Police Complaints Commission, all Special Branches routinely gave details of politically active people to the construction industry blacklist.

The Blacklisting Support Group are outraged by this reference to ‘so-called blacklisting’ organisations. There is no doubt that blacklisting occurred. It is plain, indisputable historic fact. Any attempt to belittle it is deeply offensive to its many victims and their families.

STEALING IDENTITIES OF DEAD CHILDREN

At the start of the SDS, undercover officers simply invented names to use for their cover identity (apart from ‘Michael Scott‘ (HN298, 1971-76) who stole the identity of a living person), undercover officers used fictional identities to build their cover story in the early days.

But from around 1974, after a change of management, undercovers started to use the identities of dead children and were instructed and/or expected to do so. Officers who queried this were told it was the usual process.

They searched for people who had been born around the same time as themselves, preferably with the same first name. The practice continued into the late 1990s – the most recent known being ‘Rod Richardson’ (EN32/HN596, 1999-2003).

Police have told the Inquiry that it was important that an officer have a real birth certificate in case the group they were infiltrating became suspicious and looked for one. But those same people could also find the matching death certificate.

While there are no reasons why a living person would have a death certificate, there are plenty of reasons why a birth certificate might not be found (eg, if someone was born abroad, or adopted), there is no reason why a living person would have a death certificate, and the cover would be blown. And this is exactly what happened.

Richard Clark (‘Rick Gibson’ HN297, 1974-76) was one of the first infiltrators to steal a dead child’s identity, and it blew his cover. He became active and influential in the Troops Out Movement (TOM), and then infiltrated to Big Flame.

They, however, became suspicious when Clark applied for full membership, started an investigation into his background, and confronted him with the death certificate, at which point his deployment ended.

Fictitious identities had actually offered better cover to spycops than stealing dead people’s identities.

LIFE IMITATING ART?

In last year’s hearings, police lawyers spoke of the ‘essential operational imperative’ to steal real identities But other police units doing undercover work, such as Regional Crime Squads, did not do this. So why did the SDS?

Frederick Forsyth’s novel The Day of the Jackal was published in 1971 and the film released in 1973, showing the practice of stealing dead children’s identities in just this way. So, rather than official police policy, was it instead a work of fiction that inspired this ghoulish practice? Whistleblower SDS officer Peter Francis (1993-97) said that the process was known as ‘the jackal run’ among SDS officers.

There was no justification to start the practice, and certainly none to continue after Clark was exposed. And yet, the practice continued for over 20 years. Stealing identities simply became an embedded practice in a unit that lacked accountability and effective supervision.

Very few former SDS officers seemed to have had any qualms of conscience about stealing dead children’s identities, let alone acting immorally in the dead person’s name, deceiving women into relationships, getting arrested and convicted.

In 2013, shortly after the spycops scandal became public knowledge, a Home Affairs Select Committee report insisted on the truth being told about SDS infiltrators stealing dead children’s identities and demanded all affected families be told and given an apology by the end of 2013. The Met simply ignored it. It has fallen to the Inquiry to belated start informing families.

ALL THE WAY TO THE TOP

‘Madeleine’, deceived into a relationship by ‘Vince Miller‘ (HN354, 1976-79) when she was an SWP activist, stated:

‘I have also discovered, to my horror, that MI5 has had files on me since 1970 when I was aged 16, more than 6 years before HN354’s deployment. We know the SDS was formed in 1968 and that extensive spying was happening at that time. I therefore wonder if I was spied on as early as 13, when I was a schoolgirl?

‘Miller has even reported on the pregnancy of a woman in our branch and the name her baby was to be given. This went straight to MI5.’

The SDS officers recorded extraordinary and gross levels of detail. The birth of anti-apartheid activist Ernest Rodker’s son, and a note saying that Ernest himself had been admitted to hospital, were reported and copied to MI5, as were reports about who was at Peter Hain’s family home, including his younger siblings.

Were these details requested by, or relevant to, MI5? The SDS, acting as their foot soldiers, neither knew nor cared, even when they had been instructed by MI5 or the Home Office to target particular individuals or groups.

According to police lawyers, every spycop simply hoovered up all the information they could and reported it unfiltered. It was not up to them to discern, nor is it their fault they reported irrelevant things.

Why did MI5 retain the seemingly trivial stuff for so long that it is still in their files and now being shared with the Inquiry?

FOOT SOLDIERS OF MI5

MI5 did indeed retain thousands and thousands of documents, luckily for the Inquiry, as the Met seem to have lost or destroyed almost all of the SDS intelligence reports. Witness Z, a senior officer in MI5, has made a statement on behalf of the Security Service, that confirms that the SDS has always been subordinate to MI5.

However, we won’t be getting any further explanation, as Witness Z is no longer going to give evidence to the Inquiry. No reason has been given as to why they were withdrawn.

Frankly, this is incomprehensible. Witness Z’s statement, only just released, shows they have extensive, vital knowledge about the roles of the SDS and MI5, and the cooperation between the organisations. It contains the admission that supposedly subversive organisations were not actually considered a high threat at this time, but that pressure to spy on them often came from the Prime Minister and Whitehall.

At the time, MI5 defined subversion as ‘activities threatening the safety or well-being of the State and intended to undermine or overthrow Parliamentary democracy by political, industrial or violent means’. Most, if not all, of those spied on by the SDS could not possibly be described as ‘subversive’ according to this definition.

SECRET LUNCHES

The SDS was well known to the most senior members of the Met, as well as MI5 and senior civil servants and politicians.

‘Michael James’ (HN96, 1978-83) reported that the Commissioner himself visited the SDS safe house. This practice has been confirmed for other periods by ‘Doug Edwards’ (HN326, 1968-71) and Peter Francis (1993-97) who both added that their Commissioners presented them with bottles of whisky.

From 1983, there is a programme and briefing pack prepared for Sir Kenneth Newman, the then Met Commissioner. It includes a brief profile of each member of the SDS at the time, ahead of an extended buffet lunch with the SDS officers at what is described as an ‘in-field location’.

It would be nice if the Inquiry could question Sir Kenneth about his knowledge of the SDS, unfortunately he is one of three ex Commissioners who have died since the Inquiry was announced.

But there can be no doubt that this phase of the Inquiry will put the nails in the coffin of senior officers’ claims that the SDS was a rogue unit, somehow totally secret and unknown even to the rest of the Met.

The 1975 SDS Annual Report emphasises the paramount importance of secrecy about the unit’s existence to avoid ‘an embarrassment for the Commissioner’ as well as maintaining officer security. This is a tacit admission that they knew the SDS was illegitimate. Why would there be any embarrassment if the unit were using reasonable methods to protect the public from genuine threats to their safety?

INFILTRATING, TAKING CHARGE & SABOTAGING

Police lawyers said the Inquiry should look at contemporaneous publications by the groups that spycops targeted to see how extreme the ideas were. It sounds fair enough at first, however throughout the existence of spycops, officers have written material for the campaigns they infiltrated.

From John Graham writing about the anti-Vietnam War protest in a 1969 edition of Red Camden to Mark Kennedy’s Indymedia posts, via Roger Pearce writing for Freedom, Bob Lambert cowriting the McLibel leaflet and John Dines’ anti-police section of the Poll Tax Riot booklet, it’s been common practice.

Spycops writing for campaigns pales in comparison to them being instrumental in running the organisations. A basic initial principle of the SDS, laid down by the unit’s founder Conrad Dixon, was:

‘members of the squad should be told, in no uncertain terms, that they must not take office in a group, chair meetings, draft leaflets, speak in public or initiate activity’

Despite this, the vast majority of spycops in the era begin examined, 1973-28, held positions of office in the organisations they infiltrated.

Most tend to ‘have forgotten’ the roles they had, or claimed they don’t know how they landed there. Alternatively, others say that the role was not really a position of trust at all. The institutionalised dishonesty creeps into every aspect of their evidence.

RICHARD CLARK: RISING THROUGH THE RANKS

One indisputable example of the exploitation and manipulation of both the people and the groups targeted, is the career of undercover officer Richard Clark (‘Rick Gibson’ HN297, 1974-76), who rose through Troops Out Movement (TOM) in order to get access to Big Flame.

Drawing together SDS reports and the statements of two people Clark spied on, Inquiry Core Participants Richard Chessum and ‘Mary’, James Scobie QC showed the Inquiry that Clark abused his friendship with Chessum and his sexual relationship with ‘Mary’ (and three other women) to reach his goal.

TOM was advocating self-determination for the people of Ireland and withdrawal of British troops from Ireland. Their methods were lobbying MPs, drafting alternative legislation, and raising awareness with the occasional low-key demonstration, doing talks and film screenings.

TOM had already been infiltrated, as recently as 1974, by ‘Michael Scott‘ (HN298, 1971-76) who concluded that:

‘It had no subversive objectives and as far as I am aware did not employ or approve the use of violence to achieve its objectives.’

Despite this, in a carefully prepared strategy, Clark wrote to TOM head office in December 1974 asking for a local branch to join, knowing there wasn’t one.

By February 1975, Clark had succeeded in creating an entirely new branch of the TOM. There were five founder members; Mary, Richard Chessum, his partner, another student, and Clark. Rather than infiltrating a branch, he had actively established his own one. He generated something to spy on.

Neither Mary, Chessum, nor his partner had Special Branch files on them until their involvement with Clark. Their lives were then reported upon to an extent that was both sinister and ridiculous. Their physical appearances, commentary on their body size, health issues, addresses, theatres visited, holiday destinations, right down to the brand of cigarettes they smoked. This information was passed to MI5.

WORKING HIS WAY IN

Clark had no back story. He needed to develop a place in the social network of political activists. To do that, he developed a close friendship with Richard Chessum and initiated a sexual relationship with Mary.

He also had relationships with at least three other female activists to gain position and tactical advantage. The other women were Mary’s flatmate, and two activists from the group Big Flame, Clark’s ultimate target. (His story also confirms that forming targeted sexual relationships started early in the SDS.)

As one of the founder members of the South East London branch of TOM, Clark gained access to the national movement, with an astonishing level of ruthlessness. By March 1975, he was the Secretary – the top position in the branch. He and Richard Chessum were then elected as voting delegates to the TOM Liaison Committee conference.

That move gave Clark access to the national leadership, knowing he’d be accompanied by Richard Chessum, a man with a proven track record of genuine commitment. His cultivated friendship with Richard Chessum gave him credibility.

In April 1975, Clark got himself elected as a delegate to the London Co-ordinating Committee of the Movement and the All London meeting. Clark attended a private meeting of senior members of TOM, with leader Gerry Lawless. There were only ten people at the meeting.

Clark saw his post under threat. Workers Fight was trying to take over TOM. One of them was voted to go to a London conference that would elect national posts. Clark then competed against his supposed friend Chessum for the second post and won by two votes. It’s believed one of them would have been from Mary’s flatmate, whom he had deceived into a relationship.

NATIONAL RESPONSIBILITIES

It worked – Clark was elected to the Organising Committee for London, a national position. This spycop had deceived a second woman into a sexual relationship in order to oust Chessum, a decent man who supported the movement, and take his place.

Lawless then nominated Clark for a position on the National Secretariat and he got it – he was now one of seven people in charge of the whole of TOM.

He continued to attend meetings at Richard Chessum’s home and reported on him. Mary and her flat-mate largely disappeared from Clark’s reporting, now that they had served their purpose.

Due to Lawless’s paternity leave, Clark became acting head of TOM for several months and did great damage. He cancelled delegations to Ireland. He criticised certain members. At least one prominent organisation withdrew its affiliation. And by the time Gerry Lawless returned, two members of the Secretariat had resigned.

Clark then turned against Lawless. He held a meeting with Big Flame in his flat to organise opposition to Lawless’ leadership, decapitating TOMof its long-time head.They planned a coup in the next conference. The new leadership proposed was five people, including Clark himself. Was this about TOM, or getting in Big Flame’s good books?

Clark also embarked on sexual relationships with two female members of the Big Flame. For him, sexual relationships were a tried and tested tactic of getting exactly where he wanted to go.

CAUGHT IN THE ACT

However, Big Flame rumbled him. We don’t know quite how. Telling different stories to different women and them comparing? Was he seen as Machiavellian? Or was it simply a lack of political authenticity?

It was not unusual for Big Flame to investigate new people who wanted to join if they did not trust them entirely. Members of Big Flame looked into background information ‘Rick Gibson’ had provided, and could not confirm any of it. Then, as mentioned above, they went to the government’s birth and death records archive to discover Rick Gibson’s birth certificate. And they also found his death certificate.

They confronted Clark with both. His ambitious plot to unseat Gerry Lawless was over.

Clark took flight and disappeared from the political scene altogether. Richard Chessum later saw a dossier that Big Flame had prepared, that included a letter from Clark written to one of the female activists, saying that he ‘had to go away’.

There was no retribution against Clark after his exposure. It stands out that none of the groups infiltrated were interested in violence unless in self-defence. This shows the Met’s applications to the inquiry for anonymity for spycops for fear of reprisals are highly questionable.

In this era, from Clark onwards, every single spycop took a role in the organisation they infiltrated (except for ‘Graham Coates’ (HN304, 1976-79) who was infiltrating anarchists without hierarchy or official roles). In some case officers took national leading roles. What resulted from this was not just information, but also the opportunity to have a say in the direction of the organisation, and ultimately the ability to derail that organisation.

CONCLUSION

In her statements, Diane Langford connected the spying in the past to the new Covert Human Intelligence Sources Bill rushed through Parliament just before the November hearings in 2020, which allows police to self-authorise to commit any crime. This undermines much of the point of the Undercover Policing Inquiry which is tasked to make recommendations for undercover policing in future.

In January 2020, the current counter-terrorism spycops unit listed peace protesters as extremists. One of them was the Palestinian Solidarity Campaign seeking to uphold international law and to promote peace, yet it is targeted as a problem to be undermined. Not much seems to have changed since the SDS was officially disbanded in 2008.

The Undercover Policing Inquiry hearings continue for another three weeks, after which it will be a year before there are any more.

Yesterday the police told the Inquiry said they would have behaved identically if a racist campaign had opposed a black sports team touring England. But supporting racism is different from opposing it. Equivocation between the motivations and actions of the left and far-right was apparent in the witness testimony of Madeleine earlier.

Yesterday the police told the Inquiry said they would have behaved identically if a racist campaign had opposed a black sports team touring England. But supporting racism is different from opposing it. Equivocation between the motivations and actions of the left and far-right was apparent in the witness testimony of Madeleine earlier.

Mitting vaporised any chance of that approach by asking what the specific issue was. Menon said it was whether Crampton had a relationship with a leading Notting Hill VSC member.

Mitting vaporised any chance of that approach by asking what the specific issue was. Menon said it was whether Crampton had a relationship with a leading Notting Hill VSC member.

Tranche 1, Phase 1, Day 7

Tranche 1, Phase 1, Day 7

What happened next was the stuff of fiction. Steel and Morris couldn’t afford lawyers and represented themselves in court (assisted behind the scenes by a young barrister prepared to work for free called Keir Starmer) against a large McDonald’s legal team led by a QC charging £2,000 a day. McDonald’s had objected to the whole leaflet, so Steel and Morris had to defend every word. It became the longest trial in English history. In the end there were a number of damning judgements against the fast food giant, and versions of the leaflet were being handed out in millions all over the world.

What happened next was the stuff of fiction. Steel and Morris couldn’t afford lawyers and represented themselves in court (assisted behind the scenes by a young barrister prepared to work for free called Keir Starmer) against a large McDonald’s legal team led by a QC charging £2,000 a day. McDonald’s had objected to the whole leaflet, so Steel and Morris had to defend every word. It became the longest trial in English history. In the end there were a number of damning judgements against the fast food giant, and versions of the leaflet were being handed out in millions all over the world.

Tranche 1, Phase 1, Day 6

Tranche 1, Phase 1, Day 6

Despite Soracchi’s name being in the public domain for quite some time, Mitting is insisting that nobody can say it at the Inquiry, to the frustration and disappointment of Lindsey and others.

Despite Soracchi’s name being in the public domain for quite some time, Mitting is insisting that nobody can say it at the Inquiry, to the frustration and disappointment of Lindsey and others.