UCPI Daily Report, 10 May 2022

Tranche 1, Phase 3, Day 2

10 May 2022

The late Barbara Shaw, holding the death certificate of her son Rod Richardson whose identity was stolen by a spycop

The second day of the 2022 Undercover Policing Inquiry hearings concerning the management of the Special Demonstration Squad 1968-82 included opening statements from:

Catherine Brown (representing the Home Secretary)

James Scobie QC (representing Lindsey German, ‘Mary’, & Richard Chessum)

Fiona Murphy QC (representing ‘Category F’ core participants – families who discovered that the identities of their loved ones had been appropriated by the spycops to construct cover names)

Charlotte Kilroy QC (representing ‘Category H’ core participants – women deceived into sexual relationships, as well as a child born as a result of one of those relationships, and one man deceived into a long term close friendship)

Charlotte Kilroy QC (representing Diane Langford and ‘Madeleine’)

Owen Greenhall (representing Lord Peter Hain, Ernest Rodker and Jonathan Rosenhead)

Sam Jacobs (representing Celia Stubbs)

Catherine Brown (representing the Home Secretary)

A very brief appearance, just confirming that the current Home Secretary remains supportive of the Inquiry’s work.

Opening statement of Catherine Brown

James Scobie QC (representing Lindsey German, ‘Mary’, & Richard Chessum)

‘Mary’ – one of the women who was deceived into a relationship

Richard Chessum – associated with Big Flame, Troops Out Movement and other campaigns

Lindsey German – Socialist Workers Party / Stop the War campaigner.

Scobie argued that the material disclosed by the Inquiry demonstrates that:

• There was no justification for the spycops’ infiltrations on the grounds of preventing public disorder. The true purpose was political and economic. There was no legal justification and the Government knew this.

• The Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) was really part of a large data-harvesting scheme, run on behalf of MI5, targeting anyone with left-wing politics.

• ‘Public order’ was used as an excuse, to justify the unit’s ongoing existence.

• The Government was aware that these operations were targeting lawful, democratic activities.

• The intelligence gathered by the SDS was used to blacklist law-abiding members of the public and prevent them from being employed in a wide range of jobs.

He pointed out that the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) has been mischaracterised in order to justify its being infiltrated (by over 24 SDS officers over the years). In fact, the ‘revolutionary change’ they advocated was democratic in nature, with the aim of creating equality for all. As he put it:

“The aims of revolutionary socialism are to transform society from within, re-addressing the balance of power away from the minority that holds it, to the majority that should. That process has to be democratic by definition.

“They campaigned on issues such as sexual discrimination, racism, low-pay, unsafe working conditions, unemployment and poverty. All of which needed transforming.

“They focused on building a mass movement and broad-based campaigns with the aim of helping to create a better society.”

According to ‘Colin Clark’ (officer HN80), who spent five years embedded within the SWP’s headquarters, the Party:

“were strongly opposed to government policy but were not seeking to subvert the institutions of the state.”

Scobie showed that although the unit had a purely public order remit when it was founded, by the mid-1970s this justification became increasingly contrived, as public disorder was on the decline. Instead, the unit moved towards serving ‘customers’ such as MI5, who “told them what to get and where to get it”. SDS management had regular meetings with the security services.

Between 1968 and 1971, there was an “exponential” increase in the number of SDS reports being produced, from a few hundred to tens of thousands. The vast majority contained personal details of left-wing sympathisers, rather than anything relating to public order. This is an accurate reflection of the true priorities of the spycops, not the ‘skewed’ picture the police now claim it to be. The content of the unit’s Annual Reports back up his assertion.

Right to Work march at the Conservative Party conference, Brighton, October 1980

Even the public order successes claimed by the SDS are misleading. Scobie was able to demonstrate how they did this, in Lindsay German’s experience of the Right to Work campaign.

The SDS exaggerated the potential threat of disorder and then claimed the credit for it not occurring, when in fact it was the campaigners themselves who ensured events were well-stewarded and passed off peacefully.

Scobie highlighted the Metropolitan Police’s refusal to acknowledge the racist nature of many acts of extreme violence, such as the murder in 1978 of Altab Ali. Racially motivated attacks were relatively common, yet those responsible were ignored by the SDS.

The real threats of public disorder and violence came from the far-right, yet Scobie noted that according to Detective Inspector Angus McIntosh (officer HN244), there was a deliberate policy decision, made at a high level, for the SDS not to infiltrate them.

From the (closed) evidence of officer HN21:

“From the SWP side, it was mostly shouting. From the far right thing, it was mostly physical violence.”

Instead, two Special Branch officers were reportedly (in 1968) sent by their Chief Superintendent to take tea on the lawn of one well-known fascist (later imprisoned for inciting racial hatred), Lady Jane Birdwood, and “thank her” for the information she shared with them.

Next, we heard about the guidelines applied to Special Branch’s work, and therefore to the SDS, and the way ‘subversion’ was interpreted by them. Definitions were left deliberately vague, so that legitimate political and industrial activity could be treated as ‘subversive’ and therefore fair game for the spycops.

This may explain why senior managers (and the Home Office, according to material that’s now been released) were keen to ensure that the existence of the unit remained secret, and the public never found out that these officers had been given unchecked powers to “pry into political opinions and private conduct of law abiding citizens”, and to interfere with freedom of assembly and expression.

At least nine spycops are known to have assumed positions of responsibility within the SWP. These include ‘Colin Clark’ (officer HN80) and ‘Phil Cooper’ (officer HN155), who provided incredibly detailed reports and received commendations for their work. Their reports included a lot of information about trade union activity, an area neither MI5 or Special Branch was officially permitted to investigate. The SDS bent the rules to suit themselves.

The real reason for the systematic ‘hoovering up’ of hundreds of SWP members’ data was political and economic policing. SWP activists were at real risk of being refused work and blacklisted, and this is something Richard Chessum experienced himself. This document from 1975 refers to a ‘close and mutually profitable relationship’ between the police and employers.

Members of Parliament were concerned enough about this issue back in the 1970s to ask questions about trade unionists being targeted, but the police lied to them.

Opening statement of James Scobie

Fiona Murphy QC (representing ‘Category F’ core participants – families who discovered that the identities of their loved ones had been appropriated by the spycops to construct cover names)

NPOIU officer EN32/HN596, who stole Rod Richardson’s identity

Their earlier Opening Statements (in November 2020 and April 2021) described the devastation of losing their loved ones, and the horror they suffered upon learning that their identities had been used in this morally abhorrent way.

This stage of the Inquiry is of particular importance to them as they seek to learn how the practice of using the identities of dead children began and how it came to be normalised by the spycops.

Murphy took a moment to remember Barbara Shaw, who sadly passed away last year. She had been instrumental in pursuing justice for the families affected in this way for the past decade, since learning that her son’s name, Rod Richardson, has been stolen by one of the spycops.

In 2021, the Crown Prosecution Service concluded there was sufficient evidence to bring a criminal prosecution against officer EN32/HN596, but they nonethelss decided not to press charges. They feel it is ‘not in the public interest’ as the officer was only following his unlawful training. The fact that a conviction would be likely is surely enough to prosecute him, and his unlawful mentor – who we now know to be Andy Coles (officer HN2).

The CPS told Rod Richardson’s family of their decision last year, eight years after the truth was revealed, and two weeks after Barbara Shaw had died.

The delays of this Inquiry continue to cause significant distress to the remaining families, who ask that officers now “volunteer the full truth without any ambiguity and without any economy as to that truth”.

There is one family listed whose name has been redacted from the Statement. This is due to a Restriction Order granted by Mitting, awarding both real- and cover-name anonymity to the undercover who used the name of their deceased child. This means that they too are silenced, and cannot speak up in public, cannot seek support, and:

“Against a backdrop of unspeakable trauma, the family feel degraded, humiliated, debased and silenced both in the public domain and in their personal relations. The family have been shut out from the opportunity to scrutinise whether even the process that resulted in the imposition of the restriction took proper account of the ongoing gross interference with their rights.”

The families say that the evidence they heard last year ‘crystallised’ their views, that there was no need for this ghoulish practice to have been adopted in the first place, or maintained for so many years, and they question the need for the spycops operation’s very existence.

As Murphy put it:

“the Special Demonstration Squad (“SDS”) was a secret operation, operating in isolation from and far beyond the moral and legal norms of policing; and they had every confidence that its secrets, including the immorality and illegality at the core of its practices, would remain secret.”

Murphy then provided an overview of the practice, the many contradictions and how mangers sought to justify it.

In the early years of the SDS, only one officer (‘Mike Scott‘, officer HN298) stole the identity of a deceased child. He says he did so on his own initiative. Other undercovers in those years (1968-74) simply created fictitious identities, and this worked fine. They were able to obtain driving licences, library cards, etc, in their invented names, and no deployments were compromised as a result. Regional and National Crime Squad officers continued in this way until at least 1998, again without any problems.

However, we now know that many SDS officers (approximately half of those represented by the Designated Lawyers) chose this method of constructing an identity based on the real name of a deceased child, from 1974 onwards.

It’s been suggested that this became standard procedure due to deployments based on purely fictitious identities being compromised. However there is no evidence of this being the case.

There were spycops who raised concerns about this practice, and about the moral implications, and at least one who is known to have refused to adopt this method of creating a ‘legend’. ‘Colin Clark’ chose to use a fictitious name during his time undercover (1977-82), with a passport issued and no known problems.

When deployments were compromised, this was often due to the officers themselves making mistakes – for example, ‘Graham Coates‘ (officer HN304) accidentally gave his real name when stopped for drink driving.

Richard Clark (officer HN297) was confronted by Big Flame activists with a copy of a death certificate for the person he was pretending to be (‘Rick Gibson’) and had to be pulled out of the field immediately as a result.

Whether or not this tactic originated with The Day of the Jackal book, or the film of the same name, or the KGB (!) remains unknown.

Murphy went on to say that the SDS was “an entirely misguided enterprise”, blaming the unit’s managers for perpetuating this unethical and illegal practice and a “toxic culture” of secrecy. She cited the current temporary MPS Commissioner, who recently spoke out about failures of leadership resulting in institutional toxicity that could not be explained away as just a few ‘bad apples’.

Opening statement of Fiona Murphy QC

Charlotte Kilroy QC (representing ‘Category H’ core participants – women deceived into sexual relationships, as well as a child born as a result of one of those relationships, and one man deceived into a long term close friendship)

Charlotte Kilroy QC

Kilroy began her oral statement with some very old case law – about the ransacking and seizure of property by the Earl of Halifax, in the home of John Entick, in 1762. The relevance to the Inquiry soon became apparent.

Entick went on to sue for trespass, and the resulting, 260-year old judgement Entick v Carrington is one of the most important pieces of British constitutional case law. It establishes that the state cannot issue “general warrants”, or any kind of speculative or non-specific invasion of private homes in search of evidence of crimes. This, together with the Common Law principles of personal security, liberty and property, underpins much of modern policing.

BACK TO THE FUTURE

Fast forward two centuries, to 1968. Following unrest on the March 1968 Grosvenor Square demo, the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) was set up by Special Branch and the Home Office, seemingly with any proper legal or political oversight. Very quickly, officers were creating false identities, being provided with accommodation and expenses and being deployed for years on end.

They routinely entered private homes, and were given very little direction about what to report or who to target. They gathered huge amounts of very private information and shared that with other agencies. This plainly conflicted with the bedrock of the law. However, they had a weapon the Earl of Halifax did not have: secrecy.

Charlotte then re-told the now familiar story of officer Mark Kennedy’s unmasking in 2010, which began the unravelling of the secrecy surrounding the SDS and Kennedy’s unit, the National Public Order Intelligence Unit.

It was revealed that they had entered the private homes of thousands of people and that Kennedy was one of dozens of officers who had deceived women into sexual relationships. Some even had children. All this was discovered by accident and it is only because of that accident that this Inquiry exists at all.

THE PROBLEM WITH SECRECY

“Secret surveillance powers characterise the police state and are a menace.”

This was the ruling of the European Court of Human Rights in Klass & Others v Germany 1978. Secret surveillance poses a danger of undermining, even destroying democracy, while claiming to defend it. In all democracies governed by the rule of law, covert powers are confined to the most serious threats. Secrecy is always dangerous to democracy. It corrupts, and it encourages abuse.

THE APPLICABLE LAW

Ms Kilroy QC made detailed written submissions on the applicable legal framework.

Freedom of Expression is described as “the primary right” in a democracy, because “without it, an effective rule of law is not possible”. The right to hold and share opinions without interference and without being monitored and placed under surveillance is protected in both common and international law.

The sanctity of the home, the family, and possessions is zealously protected in common law and Article 8 of the Human Rights Act and is considered absolutely sacred, just as every person’s body is considered inviolate. Any interference is considered trespass, and the burden is on the police to justify their trespasses.

Mr Sanders, representing some of the former undercovers, yesterday suggested that everything a public authority does is considered lawful until ruled otherwise by a court. That is untrue. A statutory instrument is presumed lawful, but a trespass is not. Using deception and tricks to gain an invite to someone’s home is no justification, and even where a warrant exists, it is not lawful if it allows discretion as to who the target of the warrant is, or speculative searches for evidence of crime.

THE EUROPEAN CONVENTION ON HUMAN RIGHTS

The primary focus of Ms Kilroy’s submissions is UK Common Law, nevertheless, international law is also relevant. Yesterday the police suggested it was not applicable, and Mitting appeared to agree.

This is wrong for 3 reasons:

1. The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) was applicable law at the time, and the UK was committed to comply with it. Any failure to do that must be relevant to an assessment of the statutory regulation of undercover policing, which is part of the Inquiry’s task. How can the Inquiry conclude the statutory regulation of undercover policing was adequate, if it led to the UK breaking its international human rights commitments?

2. One of the great iniquities of secrecy is that it obstructs accountability. The UK twice changed domestic law in response to ECHR rulings during the 1980s and 90s. If people had been able to raise the practices of the SDS in Strasbourg it would very likely have led to changes in law.

3. The Inquiry is tasked with examining the effects of undercover policing on individuals and the public in general. The large scale breach of people’s Human Rights and the denial of redress due to secrecy is clearly a serious effect.

INVESTIGATORY POWERS TRIBUNAL RULING IN WILSON

This case from 2021 addresses all the rights outlined above in the context of undercover policing. The Investigatory Powers Tribunal (IPT) ruled that the Met and National Police Chiefs Council had violated Wilson’s rights under Articles 3, 8, 10, 11 & 14. The ruling is summarised here.

The police lawyers yesterday sought to diminish the relevance of this case to the inquiry, by saying that it is based on the facts of that case. That is of course true, but the similarity between the facts and the impact on individuals spied on in that case, and those in Tranche 1 of this Inquiry, is impossible to ignore.

Specifically, the police’s argument – that allowing the police to make proportionate responses to demonstrations is a justification for undercover operations – was rejected by the IPT. Likewise, they cannot be considered to justify trespass.

The findings that the operations violated Wilson’s rights to freedoms of expression and association also have obvious implications for the actions of the SDS.

The IPT also ruled that two senior officers knew about the sexual relationship and others adopted a policy of “don’t ask, don’t tell”. A finding the inquiry must bear in mind when questioning managers in this tranche. The police accepted the judgment, and did not appeal any of the findings.

POLICING BY CONSENT

The whole concept of Policing by Consent is likely to be viewed by most CP;s and as fantasy of the liberal state. Some activist groups have recently declared their withdrawal of any consent.

However, the concept did provide Kilroy with some extra ammunition. For instance, Principle 5 of the Peelian Principles (1829) states that officers are injuncted at all times to uphold the historic tradition that “the police are the public and the public are the police”.

The police are only members of the public paid to give full time attention to duties that are incumbent on every member of the public. Lying and deceiving the public and trespassing on their privacy, property and intimate lives fundamentally undermines this principle.

THE 2005 INQUIRIES ACT

The police submissions yesterday sought to suggest that the applicable legal framework is not relevant to the Inquiry’s task, because Section 2 of the Inquiries Act says the Chair cannot determine individual liability. However that does not mean that the law is not relevant to the Terms of Reference in other ways.

CONCLUSIONS

Managers ought to have been well aware of the risks posed by their operations, yet in the Inquiry’s Tranche 1 period alone (1968-82), at least 6 officers engaged in deceitful relationships with numerous women.

It is a striking feature of all the evidence so far that the common law and human rights of the individuals and the impact of long-term undercover operations on those rights were rarely if ever considered:

• There was no guidance or training on privacy or relationships

• Tasking was broad brush and officers were given free rein to decide who to spy on

• There was no restriction on entering homes

• No guidance was given about what to record, and undercover officers were expected to hoover up as much information as possible

• Very little crime, disorder, or intelligence suggesting a risk to democracy was ever recorded. Usually reports showed an absence of such risks

In conclusion, Kilroy stated that it is the Category H position that these operations were incompatible with all standards of law. Scrutiny, when it finally came, came only by accident. Responsibility for that lies with the senior police officers and Home Office officials who maintained this secrecy for so long. The Police were corrupted by these practices. Their betrayal of the values of truth, integrity and honesty is made particularly clear by their willingness to lie to the courts, attacking the very institutions it was their duty to support.

Why did managers decide to abandon all the tenets of common law and the principles of policing, simply to find out how many officers to send to a demonstration, or whether people’s ideas were “subversive”? Answering this will be an important area of investigation for the inquiry.

Charlotte Kilroy QC (representing Diane Langford and ‘Madeleine’)

The experiences of these two women provide more evidence of the police overreaching their legal powers with open ended, ‘broad brush’ investigations that relied on the spycops’ discretion. Any tests of justification for targeting and reporting on them fail, something particularly egregious given the deception of Madeleine into a relationship.

Diane Langford, New York City, 1996

Diane Langford, a long time political activist, has never taken part in or been arrested for criminal activity. Despite this, at least six undercover officers infiltrated her life, and reported on her, and on private meetings held in her home. These reports contained personal information about her, often accompanied by inappropriate personal comments on her views and domestic arrangements.

Both ‘Sandra Davies’ (officer HN348) and ‘Dave Robertson’ (officer HN45) have admitted that they never witnessed any public disorder or criminal behaviour being committed by Diane or her comrades. It is difficult to see what justified the level of intrusion she suffered or the use of police resources.

Groups like the Women’s Liberation Front were targeted for no reason other than curiosity on the part of the police and/or security services. According to Sandra Davies, the undercovers were not provided with guidance or limits about entering private homes or collecting personal, private details of their targets. Robertson’s remit was likewise to gather as much intelligence as possible on his targets.

In Diane’s case, there is none of the evidence that would be required to justify an overt investigation, never mind a covert operation. This made the surveillance unlawful.

Diane now knows that the files relating to her have not all been disclosed, and requests that this happens so she can fully and properly assist the Inquiry.

‘MADELEINE’

‘Madeleine’ was deceived into a relationship by undercover Vincent Harvey (aka ‘Vince Miller’, officer HN354).

She describes how after giving evidence on this last year, she learned his real name. This led to her finding out that he went on to lead the Operation Pragada investigation into child sexual abuse in Lambeth and later became a national director at the National Criminal Intelligence Service. Madeleine was shocked by this, given what he did to her.

Former SDS officer Vince Harvey, DEcember 1999

Kilroy pointed out that Harvey was allowed to choose his own targets and use his personal judgement when deciding what to include in his reports. He took up positions of trust (such as Secretary and Treasurer) within SWP branches and used these as an opportunity to gather intelligence on party members and activities. He reported personal information expecting it to be of use to the Security Service.

Madeleine was involved in SWP activities which were entirely open and lawful, aiming to create a fairer society. Vince Harvey himself noted that their main interest was in building a working class movement, for all that there was rhetoric around ‘revolution’.

Madeleine’s evidence is confirmed by a new witness in the Inquiry, Julia Poynter, a former SWP member, who attests to both the nature of the local SWP groups and Madeleine’s relationship with Harvey.

Owen Greenhall (representing Lord Peter Hain, Ernest Rodker and Jonathan Rosenhead)

Owen Greenhall

Greenhall opened with the anti-apartheid protest at the Star and Garter Hotel in Richmond, almost 50 years ago today. Activists sought to delay the departure of the British Lions Rugby team on their tour to South Africa.

Among them was a man known as “Mike Scott” (officer HN298). Fourteen activists, including Scott himself were arrested that day and later convicted at trial. This has already been referred to the panel considering miscarriages of justice. It is an affront to justice that he deliberately deceived the defence, prosecution and court to as to his identity and the nature of his role.

There was no prior authorisation for him to participate in a demonstration leading to his arrest; he withheld key factual information that should have acquitted the defendants; the presence of an undercover officer was never disclosed to the arresting officers, the defence, the prosecution or the court; and he breached legal privilege, reporting and recording confidential conversations between defendants and their lawyers.

These concerns have already been articulated in previous statements, however we are now looking the role of SDS managers. It is clear from the evidence at the current Inquiry hearings that this was all done with the full knowledge and encouragement of SDS managers and senior officers in at all levels of the Metropolitan Police.

SDS manager Sergeant David Smith (officer HN103) was present at the first court appearance on 15th May 1972 and SDS managers monitored the case closely. Within days details had been communicated to the highest levels of Special Branch.

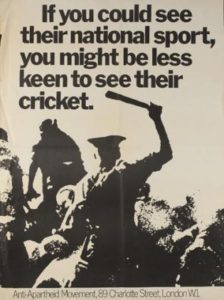

Anti-Apartheid Movement poster, early 1970s

Deputy Commissioner Ferguson Smith sent a memo confirming the Assistant Commissioner had been verbally briefed. Senior management were strongly supportive, saying HN298 had acted with “refreshing initiative” and that they should “take advantage of the situation”.

Discussions were had about assisting Scott in maintaining his deception, participating in criminal proceedings in a false identity, and even applying for legal aid. The only concern expressed was about the potential for embarrassment to the police if they ever got found out.

This apparently sent the tone and created a template for a policy of total secrecy, lack of disclosure and complete disregard for legal privilege and the integrity of the criminal justice system.

Like Scott, ‘Desmond/Barry Loader’ (officer HN13) was arrested a number of times, faced trial, and was even found guilty of public order offences. No disclosure was ever made, however the court was told he was “an informant” (not a police officer), and were asked to ensure he did not go to jail.

In both cases, SDS managers at all levels were quickly aware of and complicit in the lies, with Deputy and Assistant Commissioners and even the Commissioner himself involved in decisions to deceive the courts. There is no mention of any concern for the rights of co-defendants or the integrity of the criminal justice system.

The themes of lack of policy, training, guidance and oversight; an overriding need to preserve total secrecy of SDS and prevent reputational damage to the police; and lack of consideration for the rights of those spied upon are echoed in other areas of concern, such as the targeting of political groups, the indiscriminate collection of information and undercover officers taking active roles within political groups.

Greenhall went into some detail about the targeting of the Anti-Apartheid Movement and the Young Liberals and notes that the evidence paints a picture painted of targeting led by the undercover officers themselves, with SDS managers unable to exercise proper control.

He also cited deeply personal details recorded on his clients and their families by the SDS and passed on to the Security Services.

He concluded by citing similar concerns over the indiscriminate recording and retention of information by Special Branch as reflected in a Home Office Paper produced in 1980 which noted that some of the information collected “may not easily be justified”, reflecting that disproportionate data collection was directly related to the lack of clear management guidance and recommending independent oversight and supervision. Yet forty-two years later, here we are.

Opening statement of Owen Greenhall

Sam Jacobs (representing Celia Stubbs)

Celia Stubbs

Celia Stubbs was the partner of Blair Peach, who was killed by a police officer striking a blow to his head during a protest against racism in Southall in April 1979.

The circumstances of the tragic death of Blair Peach and the sustained cover-up that followed it is told in Celia Stubbs’ statement, and was summarised for Part 2 of the Inquiry. Undercover officers reporting on her commenced in the 1970s, and continued at least into the 1990s.

Her statement today, read out by Sam Jacobs, focused on the question how she became a target of the SDS and why intelligence was gathered on her for decades. Importantly, she found out that the Metropolitan Police still withholds information on the death of Peach.

The managers who have given written evidence generally deny any knowledge of why the Blair Peach campaign was reported on. However, when it comes to explaining the reporting on the funeral of Blair Peach, Angus McIntosh says that he would not have known to what use such information would have been put, but his understanding is that it was “for the Security Service, and for vetting, and identification/tracing”.

More was revealed in the summaries of the closed hearings the Inquiry has held. Officer HN21 recalled “one of the management” asked him to attend Blair Peach’s funeral, and it “could have been Geoff Craft [officer HN34].”

Blair Peach’s funeral, June 1979

As to why it was that the SDS wanted to report on the funeral, HN21 describes that “part of the core business was to identify people, individuals who were connected to groups.” In the instance of attending Blair Peach’s funeral, the motive “was just that” and he had not thought that there was any possibility of disorder.

As was mentioned earlier today, SDS managers did not want undercover officers to attend the rally at Southall, as it was known that uniformed officers were planning to “clamp down on the demonstrations” and dangers were “more than normal”.

Undercover officer HN41 also described the “disastrous mistake” in public order planning of closing down part of Southall.

For Celia Stubbs,

“this offers a glimpse into the information likely within the report that may have been profoundly important in exposing the approach of the police to the rally, and the violence which resulted in the death of Blair Peach.”

Crucially, HN41 recalled he was “smuggled in” to Scotland Yard to give a statement as the “Murder Squad” had heard of his presence at Southall. This shows that the officers investigating Blair Peach’s death were well aware of the SDS presence and likely knowledge of events, knowledge that was never revealed in the inquest at the time.

The fact that this has only been dealt with in closed hearings raises concerns about the ability for Stubbs and others to participate effectively in the Inquiry, as without full access it is not possible to question the witnesses properly. As Jacobs emphatically stated:

“This evidence must be revisited by the Chair.”

These revelations only add to Stubbs grief about the ongoing refusal of the Metropolitan Police to be open and honest about its actions. It is painful that time and again, it is up to her to come up with new evidence of the police’s failure. And of the Inquiry’s for that matter.

Like Diane Langford who we heard earlier this week, Stubbs submitted a Subject Access Request and received her Special Branch Registry File and some further documents from the Metropolitan Police that were not disclosed by the Inquiry.

The documents include the first information on her, with a photo attached, her relationship to Peach, and an assault by two members of the National Front for wearing an Anti-Nazi League badges.

One file shows that Special Branch information was collated on all individuals who provided a statement in respect of the killing of Blair Peach. Why was that information collected and put on file?

The disclosed reports – while heavily redacted – reveal the disdain that the Metropolitan Police held towards those seeking to hold police to account. Though she never did achieve justice for Blair Peach, her campaigning was valiant and dignified. To Special Branch, however, she was a mere “propaganda tool” for the “left wing publicity machine.”

Stubbs hopes the Inquiry understands how traumatic discovering this has been:

“I have felt more distressed but also angry. To put it bluntly, police officers took my partner’s life and then concealed the truth. The concluding job of this Inquiry is to uncover the truth.”

Video of the morning session

Video of the afternoon session

Transcript

The current round of Undercover Policing Inquiry hearings, focusing on Special Demonstration Squad managers 1968-82, continue until Friday 20 May.