UCPI Daily Report, 7 May 2021

Tranche 1, Phase 2, Day 12

7 May 2021

Evidence from witness:

‘Graham Coates’ (HN304, 1975-79)

The Undercover Policing Inquiry hearing on 7 May 2021 was entirely devoted to evidence from one witness, former officer ‘Graham Coates’, who certainly has a lot to say about the Special Demonstration Squad.

The Inquiry has prepared a lengthy summary of Coates’ undercover work, and you can read this on pages 191-206 of the Counsel to the Inquiry’s opening statement. You can also read Coates’ full witness statement. Yesterday, a related statement from the family of Coates’ contemporary ‘Jim Pickford‘ (HN300, 1974-76) was published by the Inquiry.

Grunwick strike mass picket, London, July 1977

‘Graham Coates’ (HN304, 1975-79)

It appears that ‘Graham Coates’ (HN304, 1975-79) joined the SDS in late 1975, having spent time working in various parts of Special Branch.

Coates says he was asked to attend a political meeting and report back by Detective Inspector Creamer. Shortly afterwards he was invited to join the secret unit. In his written witness statement, he recalls ‘an element of pride at having been asked’.

He was initially deployed to spy on the Hackney branch of the International Socialists (IS) – later renamed the Socialist Workers Party – in the summer of 1976. From 1977, he turned his attention to anarchist groups, including the Zero Collective and Anarchy Collective.

He also spied on the group Persons Unknown (‘PUNK’) and the Croydon branch of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP).

JOINING THE SPYCOPS

Coates first knew about the existence of the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) when in Metropolitan Police Special Branch’s C Squad, which monitored left wing political groups. At some point he realised that he was looking at intelligence which had been collected by the SDS.

Having apparently passed that assignment, Coates was asked to present himself at ‘Room 1818’. At that time, the SDS was part of S Squad, and its office was on the top floor of New Scotland Yard. When he got there, he remembers the suggestion that he join the SDS.

He was asked if he was married or in a stable relationship. On being questioned why they wanted to know this, he replied:

‘It was explained… in very general terms that they felt that an officer in a stable relationship or a stable married relationship would be a more stable character, given the likely exposure to stresses and strains of the likely work involved.’

He was told that his undercover deployment would last for four years.

Like all SDS undercovers we have heard from to date, he received no formal training for the role. Instead, he spent five months in the SDS back office, accompanying managers to the regular weekly meetings of undercovers at the unit’s safe house.

Who typed up the reports in those days? He says there was a dedicated typing pool – he definitely didn’t type them himself.

The Inquiry drew his attention to the Registry File numbers and asked who obtained the numbers for incorporation into these reports? Coates confirmed that this was the sort of administrative work he was tasked with during his time in the back office.

Coates has stated that the undercovers were asked for their opinions of these new recruits. Asked what managers were looking for, he replied:

‘I imagine that they were looking out for somebody who would not stand out in any way as obviously being a serving officer.’

SEXUAL RELATIONSHIPS : ‘BE CAREFUL’

In Coates’ written statement, he says the advice on sexual relationships, if any, was to ‘be incredibly careful’ if you were going to get involved in people’s private lives, especially if you were going to engage in a sexual relationship.

The Inquiry asked specifically what being ‘very careful’ meant.

His explanation:

‘really and truly this is not something that we advise, but if you have to, take every precaution of all kinds that you can imagine necessary.’

Coates clarified that by ‘precautions’ he meant contraception but also the:

‘common sense preservation of an identity of an individual, of a group of individuals and of the risk that would be entailed if the whole system became exposed, if that relationship became exposed.’

However it was left to individual officers to decide whether to take this advice or not and, as we heard later, many of them ignored it.

He says that he avoided sexual relationships when undercover:

‘I found the whole business of operating as an undercover officer stressful enough.’

Asked if he had any moral views on this, he said that his views had taken ‘more definite shape’ over the years, but he did feel it was wrong for an undercover officer to have a relationship of this kind with a member of the public who didn’t know who they really were.

DEFINING SUBVERSION & LACK OF TRAINING

He defined ‘subversion’ as something:

‘likely to cause disruption to an established system of government.’

Was this the system of parliamentary democracy, or the government of the day?

‘I think it was probably both.’

He talked about aims and means – and said that Special Branch would take an interest in any group with subversive aims, even if they did not have the means to make anything happen.

Asked if he felt properly prepared for his undercover role, Coates gave an emphatic ‘no.’

He went on to say that he:

‘just had a feeling that the management of the day really expected potential officers… to fully understand all of the ramifications of such a posting’

He now wishes that he had asked more questions but was not actively encouraged to do so. He thinks more formal training would have helped.

IDENTITY THEFT

Like many other undercover officers, Coates was instructed to visit the government’s birth records registry at Somerset House and to locate the identity of a dead child for his cover name. He was advised that the ‘person should not have died incredibly old’ because an older child would have ‘much more history that could be checked’.

He stole the identity of a child called ‘Graham Coates’ to form the basis of his false persona. As part of his ‘legend building’, he visited the real Graham Coates’ place of birth – something he said he did of his own volition.

The Inquiry asked if he had carried out any kind of risk assessment (even just in his head) about the possibility of being compromised or confronted with a death certificate for Graham Coates. He answered he may have considered that ‘fleetingly’ but quickly discounted it as extremely unlikely.

Coates candidly admits to not having any qualms at the time about stealing a dead child’s identity. He doesn’t know if his fellow SDS colleagues had reservations about this practice, but also said that they did not really discuss it.

His managers did not test his cover identity in any way – they trusted the undercovers’ ability to create a solid enough story. Coates says he was not warned that activists might try to test his identity, or told of any contingency plans for such a situation.

TRADECRAFT

He wasn’t able to grow as full a beard as other undercover ‘hairies’, but altered his appearance by wearing thick heavy-framed glasses. He habitually smoked a pipe:

‘I also developed the habit of always having a hole in the knee of my jeans. This was part of my general scruffiness.’

He had a driving licence in the name of ‘Graham Coates’, a rent book and maybe a library card. His cover accommodation was in North London, and he told people he was self-employed as a window cleaner.

As part of this cover, he drove a blue Mini van with a roof-rack, and carried step-ladders and other window-cleaning equipment around:

‘The job fitted the lackadaisical lifestyle I wanted as I could make my own hours.’

Coates said that he ‘chose not to be prominent’ within the groups he infiltrated. Rather, how he presented himself was connected to how he felt it might affect his safety, saying that he unconsciously ‘probably kept what I’d now regard as a Covid 19 distance from them’.

The Inquiry returned to the issue of the SDS safe houses. Were there always two during his deployment? Coates confirmed that there were, explaining that one of them changed during this time, but there were always two. He described one as a ‘large flat’.

According to his written statement, undercover officers could go into another room for a private chat with managers. He said this was something he did ‘seldom, if ever’.

He kept a standard police diary. It was used to:

‘convey in the broadest strokes the daily activities of the UCO, commencing from phoning in to start work… meeting informants at such and such a hostelry… until the early hours of the morning when you finished work.’

These diaries were submitted at the meetings. The spycops were paid for their ‘overtime’ and expenses.

CONVERSATIONS AT THE SAFE HOUSE

Coates was able to shed light on the regular meetings at the flat. There was no formal agenda. ‘It was a fairly light-hearted gathering over tea and coffee’ followed by a ‘long and moist lunch’ at a pub.

Coates was rather vague about what was discussed at these meetings but remembered them including, for example, what was defined as on- and off- duty.

The Inquiry asked why this distinction was discussed, and he said the main reason was the spycops’ claims for overtime. His were never challenged, so he assumes they ‘fell within acceptable limits’. However, he did say that in ‘one or two cases, eyebrows were raised’.

The undercovers sometimes discussed the demonstrations they attended – the discrepancies (eg in reported numbers of people attending) as well as who attended and spoke, and how the uniformed police behaved.

Were the politics of the groups being spied on discussed in the safe house? He says he had the feeling that their politics were ‘not disregarded but belittled’, and this belittling was not deliberate, it is ‘just what happened’.

He describes his relationship with his fellow undercover officers as a ‘working friendship’. He could relax with them. The group contained a wide range of personalities. They would joke together, and he remembers banter, which the managers would join in with.

‘BANTER’

In his written statement, he described ‘informal banter’ at the undercover officers’ safe house about women these officers had encountered while undercover, and ‘jokey remarks’ about sexual encounters made in the presence of managers. This behaviour was never challenged.

Coates states that Richard Clark (‘Rick Gibson’ HN297, 1974-76) had a reputation for having sexual relationships.

He also recalls that ‘Jim Pickford‘ (HN300, 1974-76) had a reputation for chasing after women and was widely known as a philanderer. A third officer, whose details he did not recall, also behaved in this way.

In his statement, he says the unit’s managers:

‘must have known it was almost bound to happen with certain individuals who had a predilection for chasing women before during and after their time with the SDS. Indeed, single men were generally not admitted to the SDS and I understood this was partly about avoiding relationships.’

Asked whether the kind of ‘banter’ would have gone down well with 1970s feminists he went much further and said that it probably would have been considered offensive by most people, even back then.

RICK GIBSON – RISK OF COMPROMISE

Asked about Richard Clark, who used the cover name ‘Rick Gibson’, he said his clearest recollection was while Coates was still working in the back office before his deployment began, when he became aware that unit’s managers were worried about Clark’s identity being compromised.

How concerned were the managers about this situation? Coates suspects the managers were more concerned about the safety of Clark’s role and function as a supplier of covert information, rather than the officer’s personal safety, adding pointedly:

‘although they would deny that, wouldn’t they?’

He thought the SDS managers didn’t want to lose this valuable source of intelligence, adding:

‘if one brick falls out of the building, maybe others will become unstable, or will be discovered to be unstable.’

They were very keen to keep the unit out of the public eye. How security-conscious were they? ‘Apparently quite,’ Coates replied drily.

MANAGEMENT KNOWLEDGE OF RELATIONSHIPS

Ever since the spycops scandal broke, a central question has been whether or not senior officers knew about the undercovers’ abusive intimate relationships.

Speaking about Clark’s sexual relationships, Coates was clear:

‘What I heard left me in no doubt that the management were aware of that officer’s behaviour.’

Senior officers:

‘could not have failed to have drawn the obvious conclusions from the comments that were being made’.

Coates explained that the sexual comments being made in conversation in the SDS safe houses were ‘of a gross nature’ have left nobody in any doubt the nature of the Clark’s relationships:

‘It was made quite plain with jokes and banter.’

Coates is extremely clear and very emphatic that there is no way anyone working in the wider SDS office at the time could have been unaware of Clark’s exploits.

At this time, the unit was run by Chief Inspector Derek Kneale. Detective Inspector Geoff Craft (and possibly DI Angus McIntosh), who would certainly have known, as would have Sergeant ‘HN368’, if they were in the unit at that time.

Pressed for details of a ‘gross comment’ of the kind he’d mentioned earlier, he reluctantly shared one example:

‘he’ll have made her bite the blankets again last night.’

Coates reiterated that the managers never openly criticised or expressed disapproval of the unit’s ‘banter’. They actually took part in what he called a ‘low level of communal humour’.

Coates accuses the managers of being ‘deliberately blind in some areas’, including these sexual relationships.

Did the spycops discuss the Women’s Liberation Movement in their safe house? As Coates remembers, their attitude and thinking was similar to many other men at the time – feminists were ‘a bunch of angry women that could be ignored’.

The Inquiry then asked Coates more about specific officers accused of sexual misconduct in this era.

JIM PICKFORD (HN300)

According to Coates, Pickford was widely known as a ‘philanderer’:

‘anybody who knew that officer, at any stage of his service, would very quickly have known what his propensities and proclivities were in that regard… he really didn’t keep anything very secret… It was common knowledge, within and outside of ‘S Squad’ [the SDS parent unit], that he could not be in the presence of a woman without trying it on.’

Coates says he witnessed this for himself. He’d have been surprised if Pickford hadn’t talked about the women in his target group.

He didn’t think Pickford did falling in love, but knew that he’d formed a relationship with a woman he met while undercover. He says he didn’t know that Jim later married such a woman.

Again, as it was the subject of safe house banter, Coates does not see how the managers could have been unaware of Pickford’s sexual relationships.

BARRY TOMPKINS (HN106)

Turning to ‘Barry Tompkins’ (HN106, 1979-83), Coates said he couldn’t recall anything about this man’s reputation with women, or any gossip about his indulging in sexual relationships. The Inquiry asked him if he could recall an anecdote circulating in the safe house about an activist woman who could lactate on demand, but Coates said he didn’t.

Documents being published by the Inquiry suggest that Barry Tompkins did indeed have a relationship whilst undercover.

PHIL COOPER (HN155)

Coates said the banter about ‘Phil Cooper’ (HN155, 1979-83) tended to be about financial matters, such as the size of his expense claims. He doesn’t remember any sexual relationships but says he would not be surprised to hear that Cooper had a ‘reputation with women’.

Asked why he wouldn’t be surprised, he went on to explain that Cooper was a ‘very charming, easy-going, light-hearted individual’ who found it easy to strike up friendships, and probably would have had ‘small to no’ qualms when it came to ‘accepting an offer of sex’ while undercover.

VINCE MILLER (HN354)

Although he couldn’t recall who ‘Vince Miller‘ (HN354, 1976-79) was when he wrote his statement, Coates now remembers him. Despite them being deployed at the same time, near each other, he says he didn’t know Miller all that well.

Coates says he wasn’t aware of his ‘reputation with women’ and knows nothing about any sexual relationships that this officer might have had.

Miller admits having relationships with four women while undercover.

Coates does not believe that the spycops gave any consideration to how these women might feel about being deceived.

TESTING FOR POTENTIAL ABUSERS?

With hindsight, Coates thinks that there should have been much stricter guidance in terms of the potential damage of such relationships to individuals and families, and that intimate relationships should have been discouraged. In particular, he suggested today that:

‘prospective UCOs [undercover officers] should be schooled for far longer, and in greater breadth, for all considerations of the work.’

When asked if he thought the men should also have been screened, so that those with a predilection for chasing women were excluded, Coates talked about why it suited the managers to ignore these sexual relationships due to the intelligence being obtained.

Coates was also asked if sexual relationships had been clearly prohibited, and if this issue been covered in training, would it have prevented them happening?

Coates replied that, in his opinion, some of the undercovers he knew would have had them anyway:

‘I don’t think it would have had any effect’.

Later in the day, Coates said he was unsurprised to hear about the high number of sexual relationships between spycops and their targets after the story became public in 2011, saying there was ‘almost a sense of inevitability’ about such things occurring.

REPORTING

Coates understood that his role was to gather information, and that:

‘no scrap of information was ever rejected as irrelevant.’

According to his statement, undercover officers were expected to ‘take information in through the skin’.

You can’t ignore things, no matter how trivial they seem – they might turn out, years later, to be ‘the missing piece of the jigsaw’ he explained. He said it was normal within Special Branch for senior officers to decide what was included in final reports, saying ‘it’s not for us’ (the reporting officers) to make such assessments.

However, he admitted to doing some filtering himself, saying he would use his own judgement and relied on his conscience as well as his experience to do so. He said that he would not report personal information – although many Special Branch reports are littered with such material.

He is not sure how complete the reporting that has been provided to him is – he says he is surprised there is not more.

PHOTOGRAPHERS

Special Branch employed covert photographers. He was often shown these pictures and asked to identify people in them. He did not photograph any activists himself.

One document shown by the Inquiry [UCPI0000011265] is a heavily censored image of an ‘anarcha-feminist’– he is asked if this is a typical example of such photos?

He agreed that it was, and explained the significance of the cropping of the image – it looks like it was a photograph that that been taken and processed by Special Branch itself.

HACKNEY INTERNATIONAL SOCIALISTS

At the start of his deployment, Coates was tasked to infiltrate the Hackney International Socialists (IS) by DCI Derek Kneale. He found it easy to infiltrate them – he hung around Dalston and got into conversation with some of its members from which they recruited him to help sell papers and invited him to meetings.

Reports attributed to Coates go back to a meeting of the Tower Hamlets branch of IS in May 1976. There are more reports from him that hot summer – many of the meetings he spied on took place at Centerprise – a cross-cultural community hub in Dalston that combined a bookshop and coffee bar, providing advice and resources, and meeting space for all kinds of groups.

These included one meeting of the North East London Workers’ Action Support Group in July 1976 [UCPI000009764], and regular members-only meetings of the Hackney IS group.

Since the Hackney IS meetings were very small, Coates was asked how much impact his presence had on the decisions made in these meetings.

He said that he retained his sense of caution throughout, and tried not to raise any suspicions. He would minimise how often he voted and abstained as often as he judged he could.

A report dated 24 August 1976 [UCPI0000010831], concerns an educational meeting organised by Hackney IS. ‘Graham Coates’ is not only listed as one of the five attendees but is named as giving a 20 minute talk on the history of the Labour Party.

Coates believes he was asked to give this talk as a way of establishing his knowledge, as a recent recruit to the IS group, and that it would have helped his credentials.

His report [UCPI0000010756] of an August 1976 meeting at Earlsmead School mentions that Paul Foot ‘spoke on the spectre of racism’.

In February 1977, Coates filed a report [UCPI0000017759] of a meeting which discussed the case of the ‘Islington 18‘ – a group of Black defendants who were arrested in North London on spurious grounds of conspiracy.

The Inquiry asked whether the SDS reported on such justice campaigns as part of their ‘any info is fair game’ approach or did they take a particular interest? Coates says the former.

BLAIR PEACH

Blair Peach

Coates says he was not made aware of any need for sensitivity around spying on those kinds of family justice campaign groups. He was asked what he knew about Celia Stubbs, who was a member of Hackney IS at the same time as him, or her partner Blair Peach. He said that he recalled seeing Stubbs at meetings, but never met Peach.

Did he remember attending a demo in Southall on 23rd April 1979? Coates asked if this was a reference to the Grunwick dispute. He had to be reminded that this was the antifascist protest at which Blair Peach was killed by police.

In contrast with his openness in answering questions about the SDS’ misogynist culture, Coates clammed up and seemed tense – he claimed not to remember any discussion of this case, or the subsequent campaigning for justice.

CLASHES BETWEEN LEFT & RIGHT

We returned once more to the subject of public disorder caused by fascist agitation, attacks, and intimidation, which has featured throughout the evidence.

In contrast to other instances, three reports from 1976-77 [UCPI0000010769] [UCPI0000011139] [UCPI0000011244] were used to show that the National Front (NF) frequently turned up at their opponents’ events and sought to intimidate and physically attack people.

A report by Coates from July 1976 [UCPI0000010659] includes a reference to a ‘negress’ in the audience talking about the West Indian Defence Committee in Brixton, who were engaged with knives and coshes ready to meet physical racialism with physical attacks.

It’s noteworthy that, throughout this period, although the NF and other right-wing groups were extremely violent, they were not being spied on by the SDS in the way that anti-fascists routinely were.

We went back to a report from June 1976 [UCPI0000009764] on a meeting of North East London Workers Action Support Group. Somebody who spoke at this meeting is reported to have said:

‘the only reason that the anti-fascist demonstrations appeared to attack the police and not the NF was because the police actively supported and protected the NF and therefore any such confrontation was an anti-fascist action… that would always be mischaracterised by the capitalist press.’

Coates explained that the view that the police always sided with the right-wing groups was prevalent. Unfortunately the Inquiry idn’t ask the obvious follow-up question – did Coates think there was any truth in this?

Coates’ October 1975 report [UCPI0000021460] about Brent Trades Council organising a picket at an NF meeting being held in Burnt Oak Library in Edgware was, he agreed typical of the reports that he and other undercover officers submitted.

GRUNWICK STRIKE

Coates was asked about his memories of the Grunwick dispute. This was a long-running strike at a north London photo processing works in the late 1970s over unfair working practices which attracted widespread support and involved mass pickets.

Coates recalled it was something to do with the discrimination faced by Asian women workers, but didn’t think he went there.

However, in his written statement, he describes his attendance with IS in some detail, and the fact that it sticks in his mind because:

‘The Grunwicks demonstrations were the only significant public order disturbance I witnessed.’

After being reminded of this, he said he thought he had gone there on one occasion.

The Inquiry highlighted part of his witness statement’s comments about violence:

‘I never witnessed any violence close-hand, but heard afterwards from other activists that people had been hit by the police. I think there were many arrests at Grunwicks for public order offences, such as obstructing the highway, offensive or abusive words or behaviour, and possibly resisting arrest.’

He then added:

‘Of course, there was always an element of a badge of honour to it – if, as an activist, you could claim that you had been hit by the police, because it just proved how rotten they were.’

SOCIALIST WORKER STRATEGIES

The Inquiry showed a report [UCPI0000010956] from September 1977, in which a member of the SWP described Grunwick as a ‘good training ground in the use of tactics on the picket line’. They added the Party should get involved in industrial disputes at an earlier stage and recommended forming ‘cells’ in factories that could persuade people to join picket lines. To this end, he suggested, there should be a list of unemployed SWP members who could join a workplace at short notice if it was thought a dispute was in the offing.

The speaker said Grunwick showed that at least a thousand comrades would be needed to attack or block the factory gates, and the plan would need to be enacted swiftly and forcefully to avoid it being stopped by police. The SWP have the ability to take such action, he said, but not the capacity to organise it.

The speaker said Grunwick showed that at least a thousand comrades would be needed to attack or block the factory gates, and the plan would need to be enacted swiftly and forcefully to avoid it being stopped by police. The SWP have the ability to take such action, he said, but not the capacity to organise it.

Coates was asked if this tallied with what he knew of SWP strategy. He said that the Party was ‘moderately OK in handling small pickets’ but lacked the ‘joined-up thinking and foresight’ to do anything on something as large scale as the Grunwick dispute.

Asked if the SWP was cooperative with the police in planning demonstrations, Coates was unsure but imagines they were.

This question has been asked of multiple witnesses now. The Inquiry seems to be implying a lack of cooperation somehow goes to justifying the deployment of undercover police – without looking at the fact that the right to free speech and assembly are protected under the European Convention on Human Rights. The Convention is clear that any interference with those rights has to be both necessary and proportionate.

As if it was somehow illegal and subversive to simply hold a demonstration without prior state approval.

The SWP was only ever minimally involved in any criminal activity, and even that tended to be maverick and spontaneous rather than planned and approved by leaders. As the SWP sought revolutionary change, how far had they got when Coates infiltrated them?

Coates retorted, ‘no further than they are now, and added that at the time of his infiltration the prospect seemed remote.

Coates’ last report on the SWP [UCPI0000017375] was dated 11 May 1977.

ANARCHY IN THE UK

At around this time, in the spring of 1977, Coates moved into the ‘anarchist field’, as he was finding the IS tedious:

‘I basically found them boring, for want of a better word, and not very active… they were always just happy to just talk about the party the party, the party, the party. But they didn’t actually do anything very much, from my point of view, to make my life interesting or more sparky,’

Rather, he had developed:

‘a fascination within me about the subject of anarchism.’

He said SDS managers were keen to accommodate the wishes of spycops, so the change was approved. A contemporary, ‘Jimmy Pickford‘ (HN300, 1974-77), had been infiltrating anarchist groups and was leaving his deployment, but Coates says he didn’t discuss his new focus with Pickford.

How did Coates prepare himself for anarchism?

‘I made myself thoroughly disreputable looking, for a start.’

In his written statement he said that he thinks he was:

‘drawn to the anarchists as I felt their unstructured and disorganised lifestyle might match my own lifestyle at that time.’

Coates described that infiltrating anarchists was, ‘to a great extent’, based on forming personal relationships with individuals.

He targeted Dave Morris:

‘because he was very cagey as an individual, but he was very approachable at the same time in lots of ways, and I knew a little about him, that he was a key mover in the area at the time.’

Morris, a life-long activist, gave an opening statement to the Inquiry at its first hearings in November 2020. Then, having learned he was spied on by Coates, Morris gave a second opening statement in April 2021.

Coates describes the two as being ‘close but not huggingly close’ for around 12-18 months.

A report [UCPI0000017641] of a Federation of London Anarchist Groups meeting in December 1976, described how Dave Morris spoke at the start, and then the meeting split into groups to discuss housing, claimants, law and education.

Coates was unequivocally clear that Morris was not a violent man. Yet, Coates filed a report [UCPI0000011003] in September 1977 where Morris had apparently said to close friends he was being ‘inextricably drawn’ towards political violence and it being ‘inevitable’ that he will resort to it. Coates conceded that, to his knowledge, Morris had never resorted to violence.

Coates also deliberately sought out esteemed anarchist Albert Meltzer in order to seem part of the scene. He met him twice at Freedom Bookshop.

In his written statement, Coates explained:

‘I suppose you might call it a little vanity project, but it was very important for me to set myself little targets like this as I found the day-to-day life undercover very monotonous.’

(By coincidence, the hearing was on the 25th anniversary of Meltzer’s death, and Freedom News published a eulogy for him)

ANARCHIST POLICE

Coates wrote articles for several anarchist publications during his deployment. He says he used his cover name (but this is more likely to mean his fake initials, ‘GC’). He doubts that he would have flagged this activity up to his managers. He suggests that they would have known, as he probably submitted copies of the publications with his reports, but this assumes that they bothered reading them.

He had written articles for IS, but found that harder as he did not share their politics. There, he asked for topics to cover and wrote what he thought people in the group would want to hear. However, with anarchists it came readily as he was:

‘expounding upon my feelings on the subject – my own personal feelings on the subject.’

He remembered writing an article about the difference between true work and exploitative work. We note this is a feat of compartmentalising, to be analysing such a subject and setting out his position, but as an act of paid work for an agency that wants to undermine the beliefs that he’s expressing.

The Inquiry described him as ‘a police officer with anarchist leanings’ – Coates did not correct this assertion. There was a sense among some of those watching his evidence that he quite liked it being put this way.

ANARCHIST GROUPS

Coates infiltrated a number of anarchist groups. He was not surprised to learn that, as an active anarchist, ‘Graham Coates’ has a Special Branch Registry File.

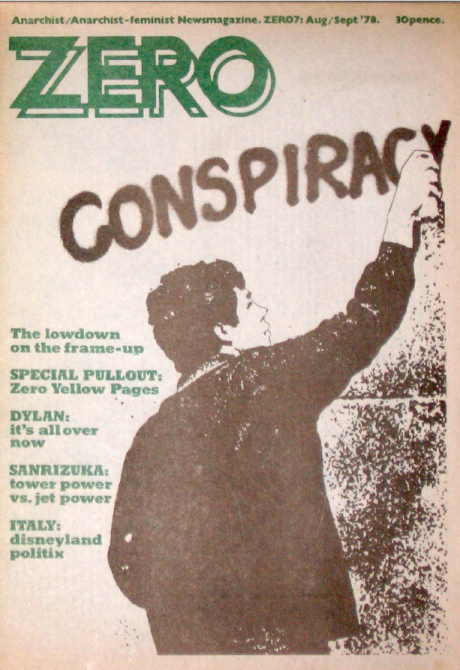

The Zero Collective produced a newsletter of the same name in the 1970s. The group was very small, commonly just three or four people in the meetings. The group didn’t commit any criminal offences or public disorder that Coates is aware of.

The Zero Collective produced a newsletter of the same name in the 1970s. The group was very small, commonly just three or four people in the meetings. The group didn’t commit any criminal offences or public disorder that Coates is aware of.

Likewise, another target, the Anarchy Collective produced Anarchy magazine. It was also a small group, with meetings often of only three to five people, held in private homes. Coates said that they were tenuously connected with the Angry Brigade, a far-left group responsible for 25 bombings in England between 1970 and 1972.

This connection, Coates recalled on being pressed, turned out to be that someone knew Scottish anarchist Stuart Christie, who had once been caught in Spain trying to assassinate fascist leader General Franco, and had later been acquitted at an Angry Brigade trial.

As for the Anarchy Collective itself, again, he said that they were not involved in any crime or disorder. He bluntly said they had not effected any change to the political system and, in his opinion, had no prospects of doing so.

Persons Unknown (known as PUNK) was a support group for three of the defendants in a legal case, and also campaigned against increased police powers. Again, he says he has no knowledge of them committing crimes or any public disorder.

He had previously said that he may have reported on another group, the East London Libertarians:

‘I don’t think they posed any more threat than any other small rag-tag organisation of any political persuasion.’

Finally, he spoke about anarcho-syndicalists like the London Workers Group. They were more linked to trade unionists and probably more effective at calling out support.

He got to know the Freedom Collective, anarchist publishers who he describes as ‘largely an organisation of wishful thinkers’.

After the Angry Brigade bombings a few years earlier, Special Branch was worried about further such campaigns. Coates saw nothing to suggest that was ever a risk. He was aware of ‘The Anarchist Cookbook’ which contained information about explosives, but said it was not widely circulated and he only once saw a copy (at the home of an Anarchy Collective member).

For someone who left IS because he felt it was all talk and no action, Coates’ choice of targets show a marked focus on publishers rather than action. It seems that he just personally preferred anarchism to socialism.

He said:

‘if every undercover officer told the truth, they would have to admit that at some point during their deployment they had some sympathy for the ideas and tenets of the group or groups that they were involved with.’

Coates is adamant that without spycops the police would not have been able to find out so much about these anarchist groups.

POINTLESS REPORTS

Coates reported [UCPI0000010997] on a September 1977 meeting of 23 anarchists to discuss ‘how should we react to racialism and anti-fascist demonstrations?’

It came in the wake of disturbances at counter-demonstrations against fascist street marches at Wood Green in April and Lewisham in August that year. This was time of a large and growing number of racist attacks in London.

The report describes the meeting as being split between pacifists who wanted public meetings and others who:

‘could hardly restrain themselves from rushing out to assault the nearest fascist/racialist.’

He readily conceded that the group was not actually overtaken by the latter faction. He was not asked what he thought the correct and proportionate response was to fascist throngs on the streets. He could not remember his colleagues ever discussing the far right.

Coates denied that report [UCPI0000021703] was his work. It concerned an anarchist meeting at the London School of Economics on 1 May 1978. It said that a speaker from the Paedophile Information Exchange had been invited, and this info leaked to the fascist National Front in the hope that they would come along to attack it so that the anarchists could provide physical resistance.

The report claimed there were about 65 people, including some up on the roof with things to throw down at any fascists who might arrive.

The Inquiry asked:

‘was the deliberate ambush of political opponents a tactic you came across?’

Coates said it was the kind of thing people might talk about but he never saw it happen.

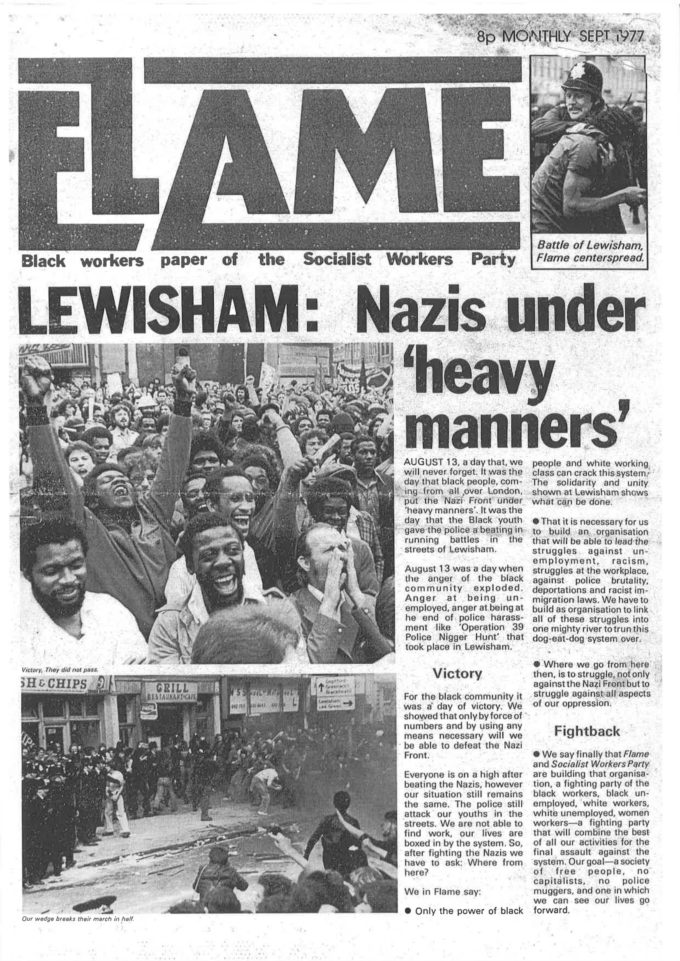

Flame, the SWP’s Black workers newspaper, Sept 1977

After that odd report, the next one [UCPI0000021710] was frankly bizarre. It said that a speaker, having agreed that a previous suggestion to burn prison gates was unworkable, suggested attacking a school.

The purpose would be to point out to pupils the uselessness of academic education. This would be done by locking pupils and staff either in or out of the building, beating up the teachers ‘with a reputation’, distributing leaflets, and doing it all within 15 minutes before leaving so as to avoid capture by police.

Coates said this was not his report and he knew nothing about such an idea. Not for the first time, it seems that Special Branch did not want to distinguish between hyperbole and actual plans. As with all the other reports mentioned, this one had been copied to the Security Service (MI5).

Despite reporting no intelligence that would build a picture of concern, managers didn’t question his continued deployment until more than a year later when he was told to switch to infiltrating Croydon SWP:

‘I think that was because they felt that my output… had become insufficient.’

He did this for a few months and, again, is not aware of the group being involved in any criminality or disorder. More than that, Coates says he never took part in any crime while undercover, and neither did the groups he infiltrated.

FRATERNISING WITH THE ENEMY

The Inquiry asked Coates about socialising with those he spied on. He said that he went to the pub with IS as a group after meetings, but not to people’s houses.

He socialised more with the anarchists because he felt more ‘at home’ among them.

His mangers never asked him about this aspect of his deployment, but would have expected it. Drinking ran a risk of Coates accidentally saying things he shouldn’t, but he still drank extensively anyway.

PREJUDICE

The Inquiry then highlighted some prejudiced language and attitudes in Coates’ reports.

A report in June 1978 [UCPI0000021776] said that following police raids elsewhere, Dave Morris had seen fit to alter his appearance quite dramatically by shaving off his beard and having his hair cut short:

‘This has revealed he has a long thin face, large Jewish nose and full lips.’

An August 1976 meeting titled ‘Women: The Fight for Equality’ was reported on [UCPI0000010823].

It describes an IS party member and school teacher, speaking to an IS meeting for the first time:

‘in addition to being attractive, she was both eloquent and forceful.’

Coates denied authorship of the report, but conceded that either way there was no need to rate the woman’s physical appearance as ‘attractive’.

The Inquiry listed a number of other objectionable observations in reports attributed to Coates. There was a reference to activists having ‘a mongol child’, a derogatory term for someone with Down’s syndrome. Another child was noted as ‘exact parenthood unknown’. Sexual orientation was commented upon, and affairs were recorded.

Coates not only tried to shrug it off as the culture of the time, he sought to justify it:

‘I can only tell you it was accepted, it was not queried… on the grounds that you never know when it might come in useful, who it might lead to, where it might lead’

RIGHT TO THE TOP

Coates recounted that the head of the Metropolitan Police, Commissioner Sir Robert Mark, visited the SDS safe house to personally congratulate the officers on their work. He remembers managers insisting on maximum attendance from all deployed undercovers that day.

Unexpectedly, he recalled that Mark made a comment when he was introduced to ‘Phil Cooper‘ (HN155, 1979-83):

‘when introduced to him, he said words to the effect of, “Ah, yes, your name should be Gold”.’

This was allegedly a reference to the size of Cooper’s expenses claims. This is a strong indication that the ‘top brass’ paid close attention to everyday details of the spycops unit. It demonstrates the importance of proper cross-examination at the Inquiry.

The Commander of Special Branch also visited to cast a favourable eye over the unit.

END OF DEPLOYMENT

Coates said that he had found the undercover life became more and more stressful as time went on. By 1979 his home life was also difficult.

‘I made an error of judgement on a particular day which resulted in my immediate withdrawal and posting back to Scotland Yard.’

This was obliquely referred to as ‘a traffic matter’ in which he told a uniformed officer from another constabulary his real name.

SDS boss Mike Ferguson (a former undercover himself) was ‘incandescent’, not just at Coates’ own indiscretion but for the potential revelation of the unit and its methods. Coates was withdrawn from the field on the spot.

This account is somewhat curious when one notes the various other indiscretions of undercovers, especially ‘Stewart Goodman’ (HN339, 1970-71) crashing his car while drunk and telling police on the scene officer he was undercover.

OFFICER WELFARE

Coates pointed out that by the time he joined the SDS, the unit had had plenty of time to set up systems to look after the spycops welfare, but it had not done so.

He said that it would have been useful for potential recruits to be given a ‘much broader, fuller, longer period of immersion’ before entering the field.

He had no debriefing or period of rest after being withdrawn from his undercover life.. He doesn’t remember being told about any support on offer.

Nobody really checked up on his welfare after his deployment ended. He says now that at the time he seemed to be coping OK, but nobody knows how they’ll react to stress in the short- and long-term. He says the managers should have been more proactive and asked. He went on to complain that he was left feeling bereft:

‘I’ve gone through all of this and now it’s as if I don’t exist’.

Like a large proportion of spycops, his marriage foundered and he separated from his wife shortly after his deployment ended.

Coates sticks by the sentiment from his witness statement, that the SDS generally did not actually protect the public from danger, but that it was nonetheless worthwhile:

‘If the SDS had never existed, I do not think disaster would have befallen the streets of the capital apart from maybe on a very small number of occasions when there were very large demonstrations. But I think the work of the SDS helped to make sure police resources were not being wasted on small demonstrations, and that larger demonstrations were properly policed.’

Full written statement of ‘Graham Coates’