UCPI Daily Report, 19 Nov 2020

Tranche 1, Phase 1, Day 14

19 November 2020

Evidence from:

Officer HN 333 (summary of evidence)

Officer HN 339 aka ‘Stewart Goodman’ (summary of evidence)

Officer HN 349 (summary of evidence)

Officer HN 343 aka ‘John Clinton’ (summary of evidence)

Officer HN 345 aka ‘Peter Fredericks’

Black Defence Committee demonstration, Notting Hill, London, October 1970

This was the final day of hearings in the first phase of the Inquiry, looking at the earliest years of the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) from its formation in 1968 to around 1972.

We heard evidence from five former undercover officers of the SDS. The Inquiry gave brief summaries of four of their careers, before the fifth, ‘Peter Fredericks’ gave evidence in person for several hours.

Once again the Inquiry’s Chair, Sir John Mitting, locked horns with Rajiv Menon QC, barrister for those who were spied upon. The bias of the Inquiry was set out in even starker terms when we discovered that, in the summary of officer HN339 ‘Stewart Goodman’, it actively hid the officer’s admissions of criminality. It’s as if the Inquiry is more on the police’s side than the police themselves.

Officer HN 333

(summary of evidence)

Temporary Mystery Man

Very little is known about this officer. Their real and cover names are being restricted, along with details of the groups he targeted.

The reason for restricting real and cover names and target group was previously set out by Mitting as:

“There is, however, a small – in my judgement, very small – risk that if his cover name were to be associated with the valuable duties which he performed subsequent to his deployment, he would be of interest to those who might pose such a threat.”

He was on duty as a plain-clothes Special Branch officer at the large anti-Vietnam War demonstration on 27 October 1968, then joined the SDS shortly afterwards.

According to his witness statement, there was tight secrecy around the SDS. There was also no formal training, though once in the field the undercovers would share their experience and knowledge. He did not use the name of a deceased child, and there was only limited guidance about choosing a cover name.

He was deployed for 9 months, into a now-defunct left wing group. He attended meetings and demonstrations, but said it was a ‘loose association’ rather than a formal organisation, so he did not have any roles of responsibility.

He gave verbal updates to SDS managers at the safe house – he said he was not responsible for writing intelligence reports.

Having become ill, he was withdrawn (via a planned process) in 1969, giving his excuses to the group. He then returned to normal Special Branch duties.

The full witness statement of HN333.

A summary of information about HN333’s deployment can be found on p122 of the Counsel to the Inquiry’s Opening Statement.

Officer HN 339 aka ‘Stewart Goodman’

(summary of evidence)

‘Stewart Goodman’, the Drunk Driver

This officer joined Special Branch in the 1960s, during which time he attended meetings of the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination.

He said “everyone in Special Branch knew about the existence of the SDS”, which contrasts with other officers saying it was a well-kept secret, or something about which there were only vague rumours.

He was married at the time the joined the SDS, but there was no welfare check to discuss the impact of his new job on his family.

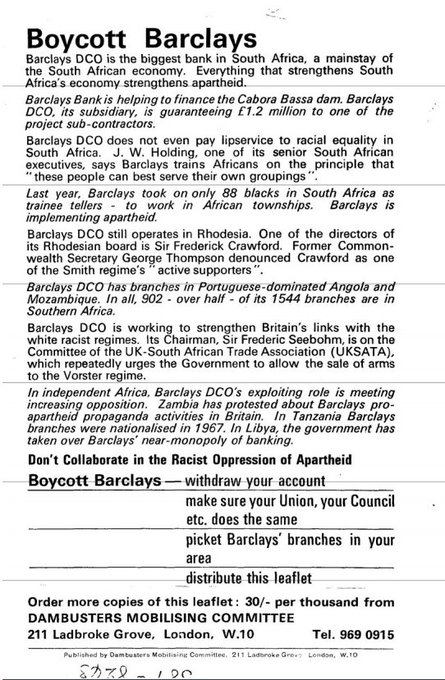

Dambusters Mobilising Committee leaflet

He was deployed undercover from 1970 to 1971, initially against the Anti-Apartheid Movement, from which he also reported on the Dambusters Mobilisation Committee. Most of his early reporting relates to this latter organisation, which was a coalition of anti-apartheid groups who opposed the construction of the huge Cabora Bassa dam in Mozambique to supply electricity to South Africa.

He subsequently infiltrated the Lambeth branch of the International Socialists (now the Socialist Workers Party), where he became treasurer (a position more than one of his contemporaries occupied in groups they infiltrated). This put him very close to the branch secretary – ‘effectively his right hand man’. He attended both public and private meetings.

While spying on the IS, much of what Goodman reported on was internal party discussions and political disputes. As well as at Lambeth branch, he also reported on the group’s affairs at a national level – including reporting on a major rift. He went to their national convention at Skegness. It appears IS were targeted because the security services believe they fell within their definition of ‘subversion’.

Goodman also said:

“MPs giving their support to protest movements was potentially of interest to Special Branch”.

The Inquiry also notes that his “intelligence evidences a particular interest on the part of IS in trade union activity”.

He did not use the name of a deceased child and says he did not have any sexual relationships.

INQUIRY COVER-UP

Non-state core participants have been worried about the Inquiry having a lawyer read a summary of an officer’s activity, with no opportunity to question the officer. What we hadn’t anticipated was the Inquiry being even more inclined to cover-up an officer’s wrongdoing than the officer themselves.

Speaking for the Inquiry, Elizabeth Campbell said:

“HN339 recalls being involved in some fly-posting while in his cover identity, but no other criminal activity. Near the end of his deployment, HN339 was involved in a road traffic accident while driving an unmarked police car, which necessitated the involvement of his supervisors on the SDS. HN339 states that he does not remember much about his withdrawal from the field, but suspects that this event may have been a catalyst for the end of his deployment.”

Goodman was not merely ‘involved in a road traffic accident’.

For those willing to wade through the statements, on page 18 of Goodman’s witness statement he said:

“I crashed my unmarked police car. I had been at a pub with activists and I would have parked the car away from the pub so as not to arouse suspicion. I drove home while under the influence of alcohol and crashed the car into a tree”.

The car was a write-off. When uniformed officers arrived, Goodman breached SDS protocol and broke cover, telling them he was an undercover colleague. Rather than arresting and charging him, they drove him home.

He was eventually charged and went to court, accompanied by his manager Phil Saunders. He believes he was prosecuted under his false identity, and that Saunders briefed the magistrates. He was convicted and fined.

Having been bailed out by his managers, he was withdrawn from his undercover role, but faced no formal disciplinary action.

INQUIRY UNDERMINING ITSELF

It is utterly outrageous that the Inquiry told the public that the only crime Goodman committed undercover was fly-posting and then, literally in the next sentence, referred to a much more serious criminal offence, for which he was convicted (with the complicity of uniformed police and the judiciary).

The Inquiry cannot claim ignorance, as they not only specifically mentioned the incident, but made a conscious choice to turn his statement from an admission of criminal culpability into a more neutral account, with no crime mentioned.

Investigating the often-corrupt relationships between the spycops and the courts is one of the stated purposes of this Inquiry, yet here they are deliberately burying examples of wrong-doing that the officers themselves admit to.

Because Goodman wasn’t called to give evidence to the Inquiry in person, there is no way to question him about the possibility of judicial corruption. Beyond that, we are left wondering what else has been covered up in this way, and lies there among the screeds pages that the Inquiry bulk-publishes after it has finished discussing a given officer’s deployment.

The full witness statement of HN339 ‘Stewart Goodman’.

A summary of information about HN339’s deployment can be found on p138 of the Counsel to the Inquiry’s Opening Statement.

Officer HN 349

(summary of evidence)

The Failed Anarchist

Both the real name and the cover name of this officer has been restricted by the Inquiry. The names of the groups he targeted have also been withheld, which has made it impossible for anyone he spied on to come forward to the Inquiry with their evidence.

He was recruited by another undercover to join the SDS after a short time in Special Branch. He was not given formal training; instead he read reports in the back office and met with other spycops before being deployed.

He grew his hair and beard and started wearing scruffy clothes, but did little else to develop his ‘legend’. His cover story was poorly developed compared to his colleagues (he had no cover job, for instance).

Deployed in the early 1970s, he was apparently not initially tasked to spy on any particular group, instead he went to demonstrations in central London and sought to get to know regulars.

He was eventually asked to target various loose-knit anarchist groups.

While at the safe house he would discuss anything and everything – including details of their deployments – with the other spycops, something other spycops have denied in their evidence to the Inquiry. In his witness statement he said:

“No topic of conversation would be off limits.”

If and when necessary, managers would take an undercover off for private chats, away from the group:

“This happened more frequently for officers who were involved in the more sensitive areas of work.”

The deployment was unsuccessful as the target group were mistrustful of strangers and did not let him build up relationships with them. Consequently, following a meeting with his managers, he was withdrawn after just nine months in the field.

He then spent time in the SDS back office, before returning to other Special Branch duties. He notes he did work with intelligence gathered by SDS undercovers though it was not marked as such. He also made requests for specific information from the SDS while at Special Branch.

HN349 noted that most Special Branch officers were “aware of the SDS and had an idea of the kind of groups they had infiltrated”. He also noted:

“It was also generally accepted by myself and fellow UCOs [undercover officers] that the Security Services provided some of the funding for the SDS.”

The full witness statement of HN349.

A summary of information about HN349’s deployment can be found on p141 of the Counsel to the Inquiry’s Opening Statement.

Officer HN 343 aka ‘John Clinton’

(summary of evidence)

‘John Clinton’ and the Subversive Pickets

This undercover served in the SDS from early 1971 until sometime in 1974. He was deployed into the International Socialists.

Prior to joining the SDS, he had been deployed as a plain-clothes Special Branch officer to report back on public meetings. Whilst in Special Branch, he had heard ‘vague whispers’ of the existence of a secret unit.

He had no formal training. He spent 3-4 months in the SDS back office, reading up on the political landscape. His cover story was basic and he gave his cover job as van driver, in case he was spotted elsewhere in London by his targets. He was give a vehicle as part of his cover.

INTERNATIONAL SOCIALISTS

Clinton was tasked by his managers to infiltrate the International Socialists (IS). From October 1971 to March 1972, many of his reports are of the IS’s Croydon branch. However, he explained that the documents do not reflect the totality of his reporting during this period. Rather, he attended various IS meetings and demonstrations across London before focusing on the Hammersmith & Fulham branch.

This branch was chosen as there was “a lot of Irish activity discussed”, which he knew was of great interest to the Met.

He found it easy to join as they were keen for new members; he turned up at meetings and demonstrations, expressing his enthusiasm for the cause. Once in, he used a ‘flaky’ persona to avoid being given responsibility in the group.

He was aware that the SDS was interested in both public order and counter-subversion issues. He said that IS was a “Trotskyist subversive group with links into Irish Groups”. He witnessed public disorder during his time undercover, but noted that any violence was not caused by IS members.

Clinton did consider IS to be subversive, writing in his witness statement:

“I witnessed a lot of subversive activity whilst I was deployed undercover. IS were constantly trying to exploit whatever industrial or political situation that existed in the aim of getting the proletariat to rise up. During industrial disputes they would deploy to picket lines and stand there in solidarity.”

He attended a wide range of public and private events, providing significant reportage of IS’s internal affairs, including details of elections and appointments, and political rifts. He also reported on trade union membership and industrial action taken by IS members. He did not join a trade union, but did go on demonstrations in support of industrial action organised by trade unions.

Other matters covered included campaigns supported by the group, such as women’s liberation, tenants’ rights and the Anti-Apartheid Movement.

Clinton noted that he had considerable discretion as to what he reported on, but was guided by what he knew Special Branch to be interested in generally. He received general tasking and updates at the SDS weekly meetings.

He wrote:

“My remit was to gather intelligence on IS. That was both with a view to public order, but also information that was relevant to counter subversion. What they were doing politically, how they were organised, and the identity of influential individuals was all important information.”

THE DEATH OF KEVIN GATELY

Clinton was infiltrating International Socialists in London in the summer of 1974, yet he made no mention of their involvement in the large anti-fascist demonstration on 15 June 1974 at which a protester, Kevin Gately, was killed.

Kevin Gately (circled), anti-fascist demonstration, London, 15 June 1974

At 6 feet 9 inches tall, Gately stood out, and his head is readily seen above the level of crowd in photos of the demonstration. This may well be why he was killed. Police charged into the crowd on horseback, lashing out with truncheons. Gately’s body was found afterwards.

The inquest found Gately died from a brain haemorrhage caused from a blow to the head from a blunt instrument. His exceptional height led several newspapers of the time to allege his death was the result of a blow from a mounted police truncheon.

It was the first time anyone had died on a demonstration in Britain for over 50 years. It was a huge cause célèbre for the left. Clinton didn’t mention this, nor any of the vigils for Gately and campaigning that followed among IS and the broader left.

It is a glaring omission that arouses suspicion. He would certainly have known of it and may well have been part of the demonstration and subsequent commemorations and events. Given the SDS’s avid focus on such justice campaigns later on, it would be very odd if their officer in IS didn’t remember it as being significant.

As with Stewart Goodman earlier, because this was an Inquiry lawyer reading out a hasty summary, lawyers for the ‘non-state core participants’ (those who were spied on) weren’t able to question Clinton about any of this.

END OF DEPLOYMENT

Clinton left his deployment in September 1974 as he had enough of being an undercover; this was supported by his managers. In one of the earliest known developed exit strategies, he used a ‘phased withdrawal’, telling the group he was going travelling.

Being undercover permanently changed him, in that it made him very private in his personal affairs.

In late 1980s, he was posted to Special Branch’s C Squad for a few months and would have received intelligence from the SDS in that role, but as it was ‘sanitised’ he would not be privy to full details of the spycops’ doings. He retired from the police after 30 years.

THE MAN WITH THE VAN

Spycop Jim Boyling with his van

It’s interesting to note that he was a van driver, with a van supplied by the SDS. This became a common part of later spycops’ deployments.

As Clinton said, it gave them an excuse if they were spotted somewhere unexpected. It also made them the group’s unofficial taxi: they would drop everyone home after meetings, thereby learning people’s addresses. If a group was planning to go on any political action, they would ask the member with the reliable van first.

It became a standard part of spycops’ fake identities across decades and units. Andy Coles (SDS, 1991-95) was known as ‘Andy Van’.

Later on, Mark Kennedy (National Public Order Intelligence Unit, 2003-2010) was known as ‘Transport Mark’, in charge of logistics for all the Climate Camps.

The full witness statement of HN343.

A summary of information about HN343’s deployment can be found on p154 of the Counsel to the Inquiry’s Opening Statement.

Five More Spycops

As if these summaries truncated enough, the Inquiry also published without summary documents relating to five former members of the SDS who have not provided witness statements:

– HN346, real name Jill Mosdell, cover name unknown. Spied on Stop the Seventy Tour, the Anti-Apartheid Movement & related groups.

– HN338, real name restricted, cover name unknown. Spied on the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign, the International Marxist Group (in particular the Notting Hill and West London branches), and the Anti-Internment League.

– HN1251, real name Phil Saunders, cover name, if any, unknown. Detective Inspector in the SDS, overseeing undercover officers.

– HN332, real name restricted. Cover name, if any, unknown. Detective Inspector and subsequently head of the SDS.

– HN394, real name restricted and cover name, if any, unknown. Detective Sergeant and then Detective Inspector in the SDS.

It wasn’t explained are SDS bosses are not even not giving statements? Are they somehow deemed irrelevant? Are they refusing to cooperate? Have they died?

It’s not clear why there appears to be no mention of HN 394 on the Inquiry website.

Officer HN 345 aka ‘Peter Fredericks’

Only one officer, ‘HN345’, gave ‘live’ evidence at the Undercover Policing Inquiry on Thursday. He was questioned by Counsel for the Inquiry, David Barr QC, and later by Rajiv Menon QC and Ruth Brander on behalf of non-state core participants. Questions were based on his written witness statement.

His mannerisms and tone obviously do not come across in the time-delayed transcript, so it is worth noting that he was usually grinning, poked his tongue in and out whilst speaking, and drew out certain words.

The opening questions are formalities, confirming that he knew the contents of the witness statement he provided, and that they are is true. Even at this, he was cocky. Asked if he was ‘familiar with the contents of the witness statement, he replied ‘slightly’.

He came across as incredibly creepy, and his evidence reiterated a number of now familiar themes: the lack of training or guidance these officers received; the bizarre claim that they all sat together in a flat for hours writing reports without exchanging information or ideas about their deployments; the ‘fishing expedition’ nature of the deployments – where everything and anything was passed on to the managers, who it was assumed would only include the information that they considered important in the final intelligence reports; the inexplicable infiltration of groups involved in political debate and even humanitarian aid; stark and shocking evidence of deep rooted sexism, racism and political prejudice; the fact that the Inquiry has only received a small fraction of the overall reporting; and the ever-present influence of “Box 500”, the code name for MI5.

GOING UNDERCOVER

Fredericks joined the police in the mid 1960s, and in the course of his ordinary policing, was offered the opportunity to do some undercover work. He “thought it sounded more interesting than road traffic duties” and agreed. Fredericks was deployed by the SDS for about six months, in 1971.

He was trained ‘on the job’ to do this ‘ordinary’ (i.e. non-spycop) undercover work. Whilst undercover he came across people involved with political groups – including the anti-apartheid Stop the Seventy Tour campaign, and the “Black Power movement”. He had not been tasked to report on either of these groups, he said it “just happened while I was doing other things”. He sent the information he gathered to his bosses.

Fredericks was asked by Ruth Brander – on behalf of Peter Hain – whether he knew that the information he had gathered about the Stop The Seventy Tour was being given to the Security Services. His lengthy response included the claim that “the system needed to know about it and I was pushing the information up”. And what about the South African security services? He didn’t have much of a response to this, managing only a weak “no”.

He explained that as a result of this intelligence-gathering, he was noticed by both Special Branch and MI5. He was interviewed and invited to join Special Branch, as a member of “C-squad” dealing with ‘domestic extremism’. He was in the section that dealt with Trotskyists and anarchists (as opposed to the one that dealt with the Communist Party of Great Britain and similar groups). He said he could not remember being briefed about any specific groups.

He said he had not heard of what was called the Special Operations Squad (SOS, later the Special Demonstration Squad) at the time. The Inquiry was shown one of Fredericks’ reports [UCPI0000005817] from his time at C-squad, before he became a member of the SOS, about a meeting on the Vietnam war where another non-state CP, Tariq Ali, was speaking.

ANOTHER AMNESIAC SPYCOP

As with most of the other officers who have so far given evidence, he said he remembered what documents proved and little more. Asked about his reporting on Tariq Ali, whose activism was so prominent at the time that his name would be used in headlines, Fredericks said he could only “remember the name very clearly but no more. It’s one of those strange things”.

While part of C-squad, he was also instructed to attend demonstrations.. At one of these demos, about the conflict in East Pakistan/ Bangladesh, he met a woman who was connected to the ‘Operation Omega’ campaign.

He gave an account of an incident he witnessed during another Bangladesh demo. He stated that he and other plain-clothes Special Branch officers had been summoned by radio back to Scotland Yard, and he was near Parliament when he spotted a police communications vehicle on fire and the female officer inside “in distress”. He said he didn’t notice any other serious trouble or violence that day:

“I didn’t notice anything to be worried about. Having said that, of course we did have the fire”.

As a result of his accidentally making connections with various political groups, he seems to have been flagged as a potential recruit for the SOS. He was approached by Ken Pendered, told that the Security Services (MI5) had written a letter commending him and that he would be transferred to this secret squad and given an undercover identity.

He was also questioned about HN326 and HN68 visiting him at his home – he can’t remember exactly when or why this took place, although he and HN326 were already acquainted. However, his pride at having been noticed by “Box” (i.e. MI5) was still evident in his demeanour, fifty years on.

NO FORMAL TASKING OR TRAINING

He confirmed that he was not given any training on the definition of ‘extremism’ or ‘subversion’, giving the somewhat vague answer that:

“what is subversive to one group could be helpful to another, or positive to another”.

He added that he had his own private views on those terms, and he cannot remember any received understanding within Special Branch on this point.

He felt the training he was given when he joined Special Branch was not particularly useful. In contrast, there was no training or guidance when he was transferred to the SOS. “We were left to our own devices”.

He had “no memory” of being instructed on what information was and wasn’t of interest. In his previous undercover work, he had been very selective in what he reported, but in the SOS he tried casting a wide net and gathering as much info as possible, from all sorts of people.

He compared himself to the provenance of antiques – “if I can be seen to be someone who knows a lot of people, different organisations, perhaps I would gain more trust”. He would hand over all the info he gathered. If he made mistakes in his report, someone would correct them. He didn’t type his own reports – there was a typing team for that – and others in the SOS decided what was relevant enough to be included.

As undercover officers, they were quite isolated, although they would have conversations at the ‘safe house’, the SDS flat. “We were on a bit of a learning curve” he explained.

In common with his contemporaries that the Inquiry had already heard from, Fredericks described being given a free rein on how he worked, negligible feedback on his reports, and no indication of what was good or bad in his work.

NEITHER GOOD NOR BAD

Were his bosses ever pleased with the intelligence he provided? “Not pleased, not dis-pleased” he answered. Indeed, the only time he can remember anyone being ‘pleased’ with his work was when that complimentary letter from ‘Box’ turned up right at the start.

Was this SOS work just an extension of the work he’d been doing in Special Branch, then? It appears not. Fredericks explained one of the main differences: “You didn’t go anywhere near the office” at Scotland Yard once you were in the SOS.

However, it should also be noted that Fredericks doesn’t think the Inquiry have seen all of his reports – there are only three reports of political meetings attended by ‘Fredericks’ in the bundle– yet he said he was “fully occupied” during his months with the squad, sometimes attending several meetings in the same day and filing several reports every week.

OPERATION OMEGA – HUMANITARIAN AID

Fredericks did not remember who had tasked him to infiltrate Operation Omega (also known as Action Bangla Desh), although it may have been Ken Pendered again. He doesn’t remember any discussions with his managers about the motivations of these groups, or being directed to infiltrate any groups in particular. He claims not to remember the names of other groups that he reported on, just Operation Omega’.

Asked about the aims and objectives of the police in infiltrating this organisation, he said they were trying “to reduce or eliminate unhelpful behaviour on the part of certain individuals within these various groups”. However, he also admitted that much of the work done by the Operation Omega group was humanitarian. Operation Omega was in fact a very small, London-based group involved in taking humanitarian aid to victims of the war in the Bangladesh (then East Pakistan) as it seceded from the Dominion of Pakistan in 1971.

Fredericks described the group as having plans to build housing for people, who had lost their homes during the war. They met up to stuff envelopes together and talk, and said that decisions were not made in his presence. “It was more admin than anything else” he said and noted that he didn’t have access to the group’s mailing list, but if he had, he would have passed it on to his superiors. He didn’t know the members very well, and he wasn’t “involved in the hierarchy”.

One of the members of the group told him that her family had donated £6,500 to the cause. “That was a great deal of money in those days” Barr suggested [it equates to approx £75,000 today] and some members of the group travelled to East Pakistan to deliver aid; he heard that one of them gave birth while in custody there. He wasn’t invited to go to East Pakistan with them.

Fredericks did attend demonstrations with the group, but can’t remember “anything special about those”. One was in Slough and involved several thousand people but was un-policed and peaceful.

“Would this have been unusual?” asked Barr, who said he was getting the impression that there were no public order concerns that day. Fredericks described them as sort of “a walk in the park on a Sunday”.

Barr said that there don’t appear to be any surviving reports by Fredericks about Operation Omega. Fredericks confirmed that he will have made two or three a week for about six months. We can only speculate as to why this might be.

FLY-POSTING WAS THE ONLY CRIME

Fredericks was also asked about an instance where he apparently went fly-posting with the group. He got no special permission from his managers to do this, he said, but on the other hand, no one was upset that he did it.

He went on to say that fly-posting wasn’t serious – “the authorities have more important things to do”. Barr agreed that it was “at the very very bottom end of the scale of criminal offending”. He was asked if Operation Omega were involved in any other criminal activity. “None at all,” he replied.

We were shown the Special Demonstration Squad’s Annual Report, written at the end of 1971 [MPS-0728971] in which Action Bangla Desh is indeed listed as having been ‘penetrated’ by the spycops, however Operation Omega is not.

When asked if there were any other officers reporting on Action Bangla Desh, or whether this would have been a reference to his work, Fredericks expressed a belief that he was the only officer deployed against Operation Omega. Nevertheless, we were also shown another report on Action Bangla Desh signed by officer HN332.

YOUNG HAGANAH – ‘WIDENING THE GEOGRAPHY’

At Operation Omega events, Fredericks met two women from the ‘Young Haganah’. He said he didn’t ‘join’ or participate in this group, or socialise with them and had no plans to infiltrate them, and no memory of being instructed to do so (by Phil Saunders or any other manager).

When asked about the connection to Israel he said “it just widens the geography”. He then admitted that he doesn’t know anything about the Young Haganah, but knew, from doing some research, that the original Haganah were involved in setting up the state of Israel decades before. The ‘Young Haganah’ were a completely separate group, who “just wanted to help people” he said. “I felt they were OK”.

Despite taking care to be someone who knew people here and there, to make himself less likely to raise suspicions, there came a time when he “knew something was wrong”. He recalled being diplomatically ‘steered away’ from meeting Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and two Labour MPs at a function, by the woman whose family had funded the Operation Omega group’s activities.

BLACK POWER

Rajiv Menon QC, on behalf of the Inquiry’s non-state core participants, pointed out that Fredericks referred to himself as being of ‘mixed heritage’ in his witness statement and asked if, in 1971, his mixed heritage was perhaps more visibly apparent than it is now.

Fredericks batted the question away:

“It’s not for me to judge. I don’t know. I don’t spend that much time looking at myself in the mirror.”

Menon asked Fredericks if he thought he was asked to target Operation Omega or the Black Power Movement because of his race.

“No. I never came across anything vaguely associated with that statement,” he replied, as if the police might have sent a white officer to infiltrate Black Power groups.

Fredericks said said he was not directed towards infiltrating the Black Power movement by anyone in the SOS. He had just met a guy at Speakers Corner and “hit it off”. He was then invited to Black Power events & meetings, which led to him meeting activists from the United States.

He knew that any such group would be considered to be of interest to Special Branch, and although he was “on the periphery, by no means at the heart of it”, he “did meet some interesting people” at this time.

Fredericks said he got on “pretty well” with some of the Black Power members, but later that he didn’t get to know them “hugely well”. A lot of his time with them was spent socialising, and playing pool, rather than discussing politics, but he thought this was a good tactic to gain their trust.

THE MANGROVE 9

Fredericks was asked if he remembered the case of the Mangrove 9. ‘Not clearly, no,’ he replied.

The Counsel’s scepticism was clear even on the transcript:

‘It doesn’t ring any bells at all? Let me see if I can help you.’

The Inquiry was then told how, on 9 August 1970 – a few months before Fredericks joined the SDS – there was a demonstration in Notting Hill about the police harassment of the Mangrove restaurant. As a result of that demonstration, nine black activists were arrested and prosecuted for riot.

There was a defence campaign set up, and their trial started at the Old Bailey in October 1971, while Fredericks was in the SDS, undercover in Black power groups.

Fredericks said:

“I was not involved closely with them. I would have read about it in the papers. I would have known something, perhaps.”

As with John Clinton’s failure to mention the death of Kevin Gately, this absence of memory is simply not credible. Even the Counsel knew it:

“And you don’t remember any conversations with any of your SOS colleagues, or anybody else in Special Branch, about this seminal event in the history of the Black Power Movement?”

Fredericks determinedly kept the lid on the can of worms:

“Definitely not. Definitely not.”

REPORTING ON RACIAL JUSTICE GROUPS

The Inquiry was shown one of his reports [UCPI0000026455] of a Black Defence Committee meeting in a pub in September 1971. The speaker was a student from South Africa, described in the report as “coloured”, and talking on the subject of apartheid. There were a dozen people (including Fredericks) in the audience.

There was a second Black Defence Committee meeting [UCPI0000026456] later that month. Solicitor Michael Siefert was the speaker, who was part of the Angela Davies Defence Committee (they were all members of the Communist Party of GB). Fredericks said he couldn’t remember much about that campaign, and he was not given any guidance on the appropriateness of spying on a justice campaign.

THREATENED BY A JOKE

Finally, he was asked about an incident he recounted in his written statement – at a meeting of around 80-90 people on the subject of violent protest, with a speaker from the USA. His witness statement included a description of worrying that he was “going to be kicked to death” after someone suggested that there was an MI5 spy in the room and he thought he was about to be accused.

He recalled the feeling “when you know you’re outnumbered and you’re in deep difficulties” – before he realised that the activists were joking, not serious – and said that he was aware “that I was involved with people who had access to and were prepared to use violence as and when necessary”.

However, when he was asked more generally about the Black Power activists, he stated that he never witnessed any violence, or public disorder, nor had he any memory of the group committing criminal offences. When asked whether they encouraged disorder, he seemed unable to give a coherent reply and said this was “difficult to answer”.

Black Power demonstration, Notting Hill, London, 1970

In fact, Fredericks’s recollections of Black Power seemed to amount to very little at all.

When asked if he thought his infiltration of Black Power was the best use of a police resource he replied, “there were times when I thought I was wasting my time, but… there were…people up there, senior people, who knew a lot more about the landscape”, who considered his deployment a good use of resources.

Back in the day, he thought it was worth keeping “an eye on what was going on, to prevent the sort of excessive behaviour that sometimes accompanies these projects”, and his view remains the same now, although he clarified “it’s not something I think about a lot”.

SEXISM

When asked about intimate relationships between undercover officers and the people they spied on, his jaw-dropping response led to gasps of horror from around the room. It is so glaringly sexist that it warrants being repeated verbatim here:

“I have, if you like, a phrase in my head which helps guide me here. If you ask me to infiltrate some drug dealers, you can’t point the finger at me if I sample the product. If these people are in a certain environment where it is necessary to engage a little more deeply, then shall we say, I find this acceptable, but I do worry about the consequences for the female and any children that may result from the relationship”.

It appears that the police lawyers (who hover in the background posing as “technical IT support” for the witnesses) may have had words with him about this during the break, because when pressed on this point later by Ruth Brander, representing non-state CPs, he appeared to recant his earlier statement a little, saying that the situation with these relationships was “hugely confusing”.

Although he admitted “you could call it deception, you could call it anything you like, it can’t be nice”, he also implied that the relationships may not even have happened, saying it is like you are “gazing into a darkened room, looking for a black cat you can’t see that may not be there…”. Speaking of the spycops who committed these abuses, he said “Perhaps – my view is perhaps they had no choice”.

Neil Woods, who was an actual undercover drugs officer, had no time at all for this as he responded on social media:

‘To compare sampling some drugs undercover to having a sexual relationship in a deployment is very twisted indeed. The casual nature of this comparison is revealing. One could argue that it’s as a result of canteen culture, the grim sexism that male dominated culture can produce. But this is beyond mere sexism, it’s disregard to the point of malice. A machine of misogyny.’

POLICE RACISM

Menon asked Frederick about racism, and Fredericks claimed that he did not encounter any hurtful racism in the police, although he talked about how disparaging things were said “with humour. I think it’s called irony”.

Menon then drew his attention to a report [MPS-0739148] (nothing to do with Fredericks) that relates to a conviction at the Central Criminal Court in February 1969.

At this point, as at numerous previous hearings, Menon clashed with the Chair, Sir John Mitting, who said:

“You are about, I think, to ask a witness about a document that is nothing at all to do with him… I’m not conducting an inquiry into racism in the Metropolitan Police for the last 50 years, I’m looking at the SOS.”

Menon pointed out that it was, in fact, an SOS document that he wanted to show.

Mitting relented without changing his position:

“I will let you do it. But this is not to be taken as a precedent for what may happen in the future. I’m really not willing to allow people to question other witnesses about documents that are nothing to do with them.”

This is a further example of Mitting’s refusal to admit the fact of institutional racism and bigotry in the Met, something which, though the Met admitted it more than 20 years ago, Mitting has called a ‘controversial’ view.

Institutional racism and sexism are at the core of the spycops scandal. For Mitting to reduce it to individual actions is a denial of the systemic nature of the abuses committed by spycops.

Allowed to show the document about the court case, Menon drew the Inquiry’s attention to details of the convicted man’s involvement in the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign and Black Power groups, then states “he has the usual attitude of coloured people towards police and authority”.

Is this the kind of ‘casual banter’ you were referring to, or something more sinister?, asked Menon.

“What I’m reading could be described as an overly wide brush-stroke”, Fredericks responded, adding:

‘we are all human beings, and no group occupies one sort of social or moral space, there is a divergence, and it’s up to us to learn to live together.’

Fredericks recognised that racism has been common in humanity, but was unwilling to agree that it has ever been a particular problem in British society, or in the police.

A FETISH FOR FOREIGN SPIES?

In addition to his obvious pride in recalling his commendation letter from MI5, Fredericks spoke about one woman from the Operation Omega group who appears to have fascinated him, because he believed she was a foreign spy.

He described her as having a “hidden agenda” – he found it hard to explain what he meant by this – he said she seemed different to the others. “She didn’t fit”, he said, but he couldn’t work out why. He was not sure if he could mention which country she was from, and after receiving permission said that she was from the United States, appearing to suggest there was a link with the CIA.

“I could be totally wrong, but it attracted my attention”, and he clearly still remembers the strength of his hunch now. “I don’t know what it was, but this woman knew what she was doing”.

Freericks was in his 20s at the time and remembered that she was older than him, and most of the others in the group. He said he was very careful – listening, and doing as little talking as possible. “We enjoyed each other’s company,” but there was mutual suspicion.

When asked if they had a romantic relationship, he said, “I’d rather not comment, but no is the answer”.

He said he would certainly have mentioned her in his reports, but didn’t gather any meaningful info (although earlier he said that he discovered her work address). This, like many of Fredericks’s answers hints at a hidden grimness to his operation. But without proper testing of the testimony, that’s all we can say.

His international spying fantasies seem to have come full circle at the end of his deployment, when – after being suddenly removed from the field – it transpired that part of the reason for this was that one of his referees (from the ‘positive vetting’ process carried out when he first joined the police) turned out to have been a Russian spy.

A SUDDEN END

Fredericks’s deployment was ended abruptly – he just stopped attending the meetings – but he said there was no consideration of possible ‘safety concerns’. He said that when he joined the unit he was told that he would be looked after, but when he left there was precious little after-care. His time undercover just ended, and there was no debriefing.

He received no guidance from his bosses about mixing with the activists he had spied on after his deployment had ended.

This led to the recounting of a curious incident in which, long after his deployment ended, Fredericks called round on someone he’d befriended while undercover – “there was no romantic involvement, I just found her interesting as a human being” -only to find out she had committed suicide not long before.

Even if we accept this at face value, it is disturbing, exposing his absence of care about the power wielded by spycops, and the lack of awareness that it is even an issue. There appears to be no part of him that felt this deception was in any way wrong. He thought – and clearly still feels – it was OK to just put his spycop persona back on for his own edification. What other activities do spycops do this for?

BITTER AFTERTASTE

Fredericks summed up his leaving the SDS:

“The way I felt was if I was no longer part of the system, then my existence doesn’t matter, my opinion doesn’t matter, get on with the rest of your life”.

He still seemed bitter about this. He did see a psychiatrist after his deployment ended, however he said he doesn’t know why his managers sent him to see someone who had no understanding of undercover policing: “The whole thing was a waste of time”. He said he did not attend any of the SDS social events or reunions.

Despite expressing the belief that the spycops’ techniques were more effective than normal Special Branch operations, and that being more deeply embedded with the activists meant he was able to gather more info from them. “I have my views,” he said, “but I’m ready to admit that I’m wrong”.

However, his creepy answers, and his unrepentant tone and demeanour throughout the questioning suggest that is not really the case.

COPS has produced a report like this for every day of the Undercover Policing Inquiry hearings. They are indexed on our UCPI Public Inquiry page.