UCPI: Weekly Report 2: 9-13 November 2020

Undercover Policing Inquiry

Undercover Policing Inquiry

Weekly Report 2

9-13 November 2020

After seven days of opening statements, and six years since it was first announced, the Undercover Policing Inquiry finally started taking evidence from witnesses this week.

This phase of the Inquiry concerned the earliest days of the Metropolitan Police’s spycops unit, the Special Operations Squad (later called the Special Demonstration Squad), for the years 1968-72.

The week began with the final opening statements from the significantly affected people whom the Inquiry has designated ‘core participants’.

HARROWING STORIES

Some came from the women deceived into relationships by officers, many of whom were directly responsible for the uncovering of the spycops who abused them. We touch on their accounts here, but cannot do full justice to these often harrowing stories.

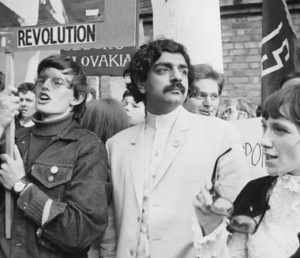

On Wednesday, we heard from the very first witness, Tariq Ali. A 77-year old journalist, writer and broadcaster who has been politically active most of his life, Ali was spied on by many undercovers, right from the inception of the units in 1968 through to the 2000s. And for the first time we heard the undercovers themselves, with three sessions on the final two days from officers who were part of the unit when it was formed.

Given breadth of the hearings, in this report we will focus on bringing out the main themes and highlights of the week, rather than going into specific detail. All of the detailed daily reports can be found on our UCPI public inquiry page.

ONGOING PROBLEMS

The opening statements heard this week powerfully repeated points those who were spied on have been arguing for years.

They put the case that in order to get to the truth, we need to know:

- Cover names and real names of the spycops. These have still not been released. Lawyer Heather Williams reiterated that with the Inquiry only giving an identifying number for spycops, it is impossible for spied-upon people to actually know they were spied upon, and be able to come forward and give evidence. We will be left with just the officer’s unchallenged account of their activities.

- Information about what they did during their deployments, and which groups they targeted. We know that more than 1000 groups were spied on, yet less than 150 have been named. When they were on holiday with people they spied on, was this ordered or sanctioned by their managers?

- Photographs of the spycops, as they looked at the time, as this is likely to have far more effect jogging people’s memories. Tariq Ali said if he had been shown a photo of ‘Dick Epps‘ (who spied on him in the 1960s) he might have been able to recollect more about him. Non-state core participants have provided the Inquiry with personal photographs but the Inquiry has chosen not to publish them.

- What is in the files: what data was gathered about individuals and the groups they were part of? The vast majority of non-state core participants have been provided with nothing at all so far. A small number have been given access to the ‘hearing bundle’, but this 5,500 page stack came just five weeks before these hearings began; far too much to comprehend, while still but a fraction of the million pages the Inquiry has.

Another point reinforced was the demand, argued for years now, that the Inquiry’s Chair, Sir John Mitting, urgently needs the assistance of an advisory panel, made up of people with more life experience and expertise than him. It is clear he lacks the understanding to investigate the institutional racism and sexism which lie at the heart of this scandal.

These initial problems with the Undercover Policing Inquiry, and more, are detailed in our report from last week.

NEW PROBLEMS: LIVE STREAMING & REPORTING

Sir John Mitting

Although this was already known about last week, the loss of public access to the live-streaming of the hearings from Wednesday morning has caused even more than the expected difficulties. A few things changed in light of protests from those attending, but there are still significant problems for those present and those prevented from attending.

There is considerable upset that people could only follow it properly by travelling to central London during a pandemic. However, Mitting is still flatly refusing to live-stream the whole thing on ‘security grounds’, even though other inquiries dealing with sensitive material, such as Grenfell and Manchester Arena, are live-streaming their hearings.

It’s clear it’s technically possible; it was done for the seven days of opening statements. Indeed, Mitting is still permitted his own personal live-stream, and two more are in the rooms provided for no more than 60 people to watch proceedings. The rest of the world had to deal with video of a live transcript of what was being said. One core participant trying to follow it described it as watching ‘speeded up Ceefax’.

IMPOSSIBLE TO FOLLOW

Another problem was that many of the documents being referred to were not shown, making it near impossible to follow some of the key details. The video feed couldn’t be rewound to check things that had been said. If you missed something, that was it.

This led to outright anger from some of the media, as well as victims’ lawyers. Journalists said it was making it impossible for them to report on issues. Many people trying to follow it from elsewhere were bitterly frustrated with how difficult it had become. These complaints resulted in some minor improvements such as a different video process and the documents being released on the same day.

The Inquiry video venue is also proving problematic for those attending; the two live-stream rooms are windowless and unventilated.

CARLO SORACCHI

Spycop Carlo Soracchi

Another significant issue this week is Mitting’s continuing refusal to let the real name of spycop ‘Carlo Neri’, which is Carlo Soracchi, be used in proceedings. This is on the application of his ex-wife.

Soracchi was deployed 2001-2006, infiltrating trade union, socialist and anti-fascist groups.

Mitting’s ban on anyone saying his real name has affected two of the women he deceived into relationships, and the Blacklist Support Group (BSG).

As a result, Dave Smith of the BSG was unable to give his Opening Statement. This is despite the fact that Soracchi’s name has been out in public for quite some time, reported in newspapers and on social media.

WHAT HAVE WE LEARNED IN THE SECOND WEEK OF UCPI HEARINGS?

One of the most shocking facts to emerge this week is that many of the abuses, previously portrayed as the unsanctioned acts of rogue officers that were only perpetrated in recent years, have all been going on since the very beginnings of the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS). These include:

- Relationships with activists. Far from being some recent deviation, spycops were forming deceitful intimate relationships with activists from 1968 onwards. These include a long-term sexual relationship between ‘Mary’ and spycop ‘Rick Gibson’ in 1975, and the strong indication of officer Helen Crampton having a relationship with an activist within weeks of the SDS’ foundation in 1968.

- Travel to other countries. Whistle-blower Peter Francis genuinely believed that he was the first spycop to be deployed abroad when he travelled to Germany in 1993. Yet ‘Doug Edwards’ (HN326), who left the job in 1971, stated he ‘went to Brussels with this other officer whose name I can’t even mention’. Evidence also showed that another of the undercovers travelled to Scotland in 1969.

- Attending family events of people they were spying on. Birthdays, weddings, and funerals were all attended by spycops as far back as 1969. Not only were the details of private family occasions collected by the State, but memories (and many of the photographs) of them are now marred by the knowledge that one of the people there was the very opposite of a friend.

POLICE FOCUS ON VIOLENCE

A repeated theme this week has entailed barristers for the Inquiry asking about the violent tendencies of protestors, and the protestors emphasising the peaceful nature of most of the groups and campaigns they were part of.

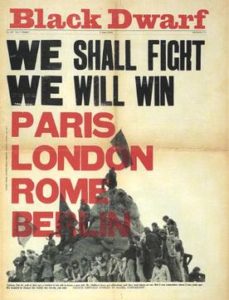

Black Dwarf, June 1968

Back in October 1968, protestors were asked not to bring fireworks and marbles to the demonstration against the Vietnam War, let alone anything else. Tariq Ali edited left-wing magazine Black Dwarf which published an article titled ‘Softly, Softly’ which stressed that, to ensure the protestors’ buses made it to the demonstration, nothing should be carried that could give the police cause to stop them.

A decade later, Ali was the Socialist Unity parliamentary candidate in Southall. During a confrontation between the National Front and anti-racists, local organisers put Ali in a safe house to keep him out of any trouble.

Police raided the house and the occupants, including Ali, were made to run a police gauntlet as they were ejected. Ali was truncheoned so severely that he passed out. The skull of the man he was with was fractured, leaving him in a coma for five months.

That was the same day, and in the same area, that Blair Peach – who we have already heard about in this Inquiry – was killed by the police. When the police unit responsible for killing Peach had its lockers searched, weapons found included a crowbar, metal cosh, whip handle, stock ship, brass handle, knives, American-style truncheons, a rhino whip and a pickaxe handle.

When considering which groups were the most violent and heavily armed, the police – with their arsenal of illegal weapons, aggressive attitude and fatal injuries – were clearly more of a threat than the activists.

Tariq Ali told the Inquiry in a written statement:

‘my strong feeling is that this Inquiry is likely to be a monumental waste of time. This is because the direction of travel is clear from the questions – to dissect the politics of the victims of police spying, and therefore to turn the spotlight away from the actions of the police. This is the politics of “blame the victim”.’

CREDIBLE THREAT OR DAFT IDEAS?

In order to continue operating, the SDS and other undercover officers had to convince superior officers that what they were doing was worthwhile. The groups they were infiltrating had to be seen as a credible threat to society.

Tariq Ali

In some cases, police provocateurs provided evidence by creating it themselves. Tariq Ali described a group of ‘hippy anarchists’ who spent the night in the offices of Black Dwarf. The group made a crude painting of how to make a Molotov cocktail on one of the walls, just in time for it to be ‘found’ during a police raid.

This tactic of provocation is seen over and over again throughout the entire history of the spycops, no matter what acronym they used.

Taking just one spycop that we know of, Bob Lambert, as an example, provocation ranges from writing or co-writing articles, such as the ‘What’s Wrong With McDonald’s?’ leaflet, to allegedly planning and committing arson by placing a timed incendiary device in the Harrow branch of Debenham’s in 1987.

Once again, this behaviour must be contrasted with that of the spied-upon groups; in 1968 the VSC were actively expelling groups that wanted to use violence on the anti-war marches. In many cases it is clear that the police were creating a self-fulfilling prophecy. The factor which made groups a ‘serious, credible threat’ was the spycops themselves.

FROM THE (POLICE) HORSE’S MOUTH

This assessment is borne out by evidence given by several spycops this week. Seemingly unaware that they were undermining their own justifications, various officers described the groups they had infiltrated as ineffectual at best, and deluded at worst.

As officer ‘Doug Edwards’ said on Friday:

‘They got an exaggerated idea of their own importance. They sort of had daft ideas’

‘Don de Freitas’, SDS officer HN330, infiltrated Havering International Socialists in 1968. His evidence portrayed a peaceful group, whose aims were not subversive, with most members ‘unwilling to support civil disobedience or terrorism’ (as if the two activities were comparable).

John Graham, who infiltrated Camden Vietnam Solidarity Campaign in the same year, viewed the members as ‘revolutionary’ because, even though they eschewed violence, they sought a change of government by trying to ‘persuade people to their point of view’.

Edwards, who in 1969 reported on the ‘Action Committee Against NATO’, said ‘I do not remember what the group stood for or what they did. I do not remember how I infiltrated the group or why I infiltrated them’. Obviously, it made very little impression on him. This is not what we’d expect from a dangerous group committed to serious disorder, which is what the SDS claims it existed to spy on.

There are many more examples of this attitude and experience from officers in our daily reports.

IF THEIR TARGETS WERE A THREAT, WHY WEREN’T SPYCOPS TRAINED?

Even before the officers’ evidence that the groups were not actually a serious risk to public safety, there is the lack of training to consider. If the spycops were indeed being sent to infiltrate dangerous organisations which threatened society, why weren’t they better prepared?

It was clear from the police statements there was a lack of direction in how to begin approaching their targets, exactly which groups to target, or other ‘fieldcraft’. ‘You had to play it by ear,’ ‘Doug Edwards’ explained.

If we’re to believe the Inquiry when it says spycops must have anonymity because, even now, being named would risk their lives, they need to explain why officers were left to do the job on a whim instead of being given instructions.

Spycop Joan Hillier asserted that SDS officers didn’t really need training as they were all experienced Special Branch officers (despite Hillier herself only joining Special Branch shortly before the SDS was formed):

‘Instinct would tell you what you shouldn’t do and what you should do.’

Officers would instinctively know not to get involved in people’s personal lives, form intimate relationships, commit crime, or appear in court under a fake identity, she said.

What Hillier refers to isn’t actually instinct, it’s personal individual morality. If it allows the officer to spy upon grieving families, undermine anti-racist and anti-fascist campaigns, and sabotage groups working for a healthier global environment – all whilst using the stolen identity of a dead infant – it is corrupt.

The fact that spycops did actually do the things Hillier lists them ‘instinctively’ avoiding, when she was an officer and afterwards over generations of deployments, shows it was not left to the individual, it must have been suggested and encouraged.

INSITUTIONAL RACISM & SEXISM

Undercover political policing’s core traits of institutional racism and sexism aren’t news to anyone who has been following this topic, but the more evidence is heard at the Inquiry, the more inescapably obvious it becomes.

Phillippa Kaufmann QC

Some of the most shocking testimony this week came from the women activists who were deceived into intimate and often long-term relationships by spycops.

Phillippa Kaufmann QC and Heather Williams QC spoke on behalf of over twenty of them; we cover this in detail in Monday’s summary of events. Kaufmann’s written statement gives further details of each woman’s story, and we strongly recommend that you read it.

Kaufmann also highlighted how both opening statements last week by Counsel for the Inquiry and whistle-blower spycop Peter Francis severely understated the role the women have played in exposing the spycops scandal. It was the women who, in the aftermath of their ‘loved one’ disappearing, uncovered the truth. Their unflinching determination cannot be overlooked.

Trying to summarise their evidence in this report cannot do it justice. Many of their experiences, in their own words, are gathered on the Police Spies Out Of Lives site and should be read there.

On Tuesday, the leading focus was the targeting of Black family justice campaigns and groups. In particular, we heard from the barristers representing Doreen and Neville Lawrence, The Monitoring Group, and Mike Mansfield QC. The Inquiry was reminded again of how it has an uphill struggle to even convince these core participants that it is capable of preventing yet further injustice, let alone of tackling the issue of institutional racism.

‘YOU WILL BE SILENCED’

Sir John Mitting, who is so sure of his own lack of bias that he’s refused input from any perspective other than his own, has treated Rajiv Menon QC, barrister for the victims of spycops, very poorly.

Rajiv Menon QC

As the very first police witness gave evidence, Menon wanted to ask a series of questions. Mitting was clearly unhappy with this, describing his own decision to permit Menon questions on a single issue as ‘exceptional, and I do not propose to invite you to ask questions on any other topic’.

Menon tried to protest and explain why it was important for the non-police core participants, at which point Mitting’s hostility became overt, telling Menon to obey or ‘you will be silenced’.

On Wednesday, Menon questioned Tariq Ali about a closed meeting of the Stop the War Coalition steering committee in 2003. As the public were not allowed at this meeting, the report must have come from a committee member or a recording device.

Mitting’s reaction to this simple statement was extraordinary: immediately and forcefully interrupting to warn Menon that the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 prohibits any reference to intercepting communications unless Mitting deems it necessary in advance. ‘You will be committing an offence if you persist’, he intoned. ‘I would warn you not to’.

Menon, a barrister of 26 years’ experience and well aware of the law, explained that he was talking about the committee being bugged by a recording device, rather than an interception of communications, and therefore, the Act doesn’t apply. Mitting apologised, but it’s clear that he is giving Menon very little credit, and even less chance to pursue vital lines of questioning.

POLITICAL POLICING

Mitting’s attitude and performance so far fall completely in line with the overarching theme that the State and the spycops are there to support each other in maintaining the norms and values of the current government.

Spying upon anyone who they wanted to spy on was not only justified, but good, simply because they did it. National security, public order, and the convenience of the government of the day were fully interchangeable concepts for them. Any intrusion was justified because every citizen is a potential subversive.

Joan Hillier said that personal details – dates of birth, home addresses, etc – of those not even suspected of anything untoward would be routinely added to Special Branch files ‘in case it was needed in the future’.

By the spycops’ own admission, their aims were hazy, their training ranged from the informal to the non-existent, and they often didn’t feel like they accomplished anything.

On Thursday, Counsel to the Inquiry David Barr quoted from spycop John Graham’s written statement on Special Branch’s role regarding policing political groups:

‘I understood the role of Special Branch to be carrying out enquiries concerning the security of the State, in other words gathering intelligence on activities that sought to undermine the status quo, the government of the day and the political establishment’.

The conflation of national security with the convenience and policy of the government has always been a central factor in what spycops do. This Inquiry is, thus far, no different from the spycops’ operations.

WHAT NEXT?

There will be three more days of evidence from police (Monday, Wednesday and Thursday), with the possibility of unfinished things being heard on Tuesday and/or Friday.

After that, the Inquiry will take a break to assess what it’s heard. It will be back next year for another batch of hearings covering the SDS 1973-82. That’s currently expected to be around April 2021.

Hearings concerning the SDS 1983-1992 are expected in the first half of 2022, and those examining the SDS 1993-2007 are likely to take place in the first half of 2023.

Some time later there’ll be hearings on the National Public Order Intelligence Unit 1999-2011, then other undercover policing, then mid and senior rank officers, other agencies and government departments.

The Undercover Policing Inquiry has no set end-date, but is expected to perhaps conclude around 2026.

COPS will be live tweeting every hearing, producing a summary every evening, and a weekly report like this one at the weekend. All our daily and weekly reports, and our UCPI FAQ, are linked on our UCPI Public Inquiry page.

Great summary. Any idea what would happen if 73 year old Mitting has health problems and has to withdraw before he gets to the finale in 2026 or beyond?

We’ve already had this issue – the Undercover Policing Inquiry was set up in 2015 with Lord Pitchford as its Chair. He developed motor neurone disease and stepped down, at which point the Home Secretary appointed Sir John Mitting. If he were to step down for any reason, the Home Secretary would appoint another senior judge to the post.